Congenital peritoneal encapsulation: A review and novel classification system

Aneesh Dave, James McMahon, Assad Zahid

Abstract Congenital peritoneal encapsulation (CPE) is a very rare, congenital condition characterised by the presence of an accessory peritoneal membrane which encases a variable extent of the small bowel. It is unclear how CPE develops,however it is currently understood to be a result of an aberrant adhesion in the peritoneal lining of the physiological hernia in foetal mid-gut development. The condition was first described in 1868, and subsequently there have been only 45 case reports of the phenomenon. No formal, systematised review of CPE has yet been performed, meaning the condition remains poorly understood,underdiagnosed and mismanaged. Diagnosis of CPE remains clinical with important adjuncts provided by imaging and diagnostic laparoscopy. Two thirds of patients present with abdominal pain, likely secondary to sub-acute bowel obstruction. A fixed, asymmetrical distension of the abdomen and differential consistency on abdominal palpation are more specific clinical features present in approximately 10% of cases. CPE is virtually undetectable on plain imaging, and is only detected on 40% of patients with computed tomography scan. Most patients will undergo diagnostic laparotomy to confirm the diagnosis.Management of CPE includes both medical management of the critically-unstable patient and surgical laparotomy, partial peritonectomy and adhesiolysis.Prognosis following prompt surgical treatment is excellent, with a majority of patients being symptom free at follow up. This review summarises the current literature on the aetiology, diagnosis and treatment of this rare disease. We also introduce a novel classification system for encapsulating bowel diseases, which may distinguish CPE from the commoner, more morbid conditions of abdominal cocoon and encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis.

Key words: Congenital; Encapsulation; Peritoneum; Cocoon; Sclerosis

INTRODUCTION

Congenital peritoneal encapsulation (CPE) is a very rare, congenital malformation of the gastro-intestinal tract. It is characterised by the presence of an accessory peritoneal membrane which covers a variable extent of the small bowel. This in turn creates an accessory extra-peritoneal sac in which the bowel is contained. The membrane is morphologically and histologically identical to peritoneum. The condition is often asymptomatic, detected incidentally during routine imaging or surgery and even in posthumous dissection. However, CPE also remains a rare but important cause of recurrent, undifferentiated abdominal pain and sub-acute small bowel obstruction.The condition was first described by Cleland[1]in 1868 as a ‘secondary sac bounded by omentum and meso-colon, and communicating with the general sac by means of a small aperture'. Since this time, it has been described in less than fifty cases. To our knowledge, there has been no prior definitive, systematised review of CPE, and therefore the condition has remained poorly understood, underdiagnosed and mismanaged. This review attempts to integrate all the literature available to provide an understanding of the aetiology, pathology, diagnosis and management of this rare and unusual condition. In addition, we provide a novel classification system for encapsulating bowel diseases, which categorises CPE and the similar phenomena of abdominal cocoon and encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis (EPS) in a histomorphological manner.

METHODS

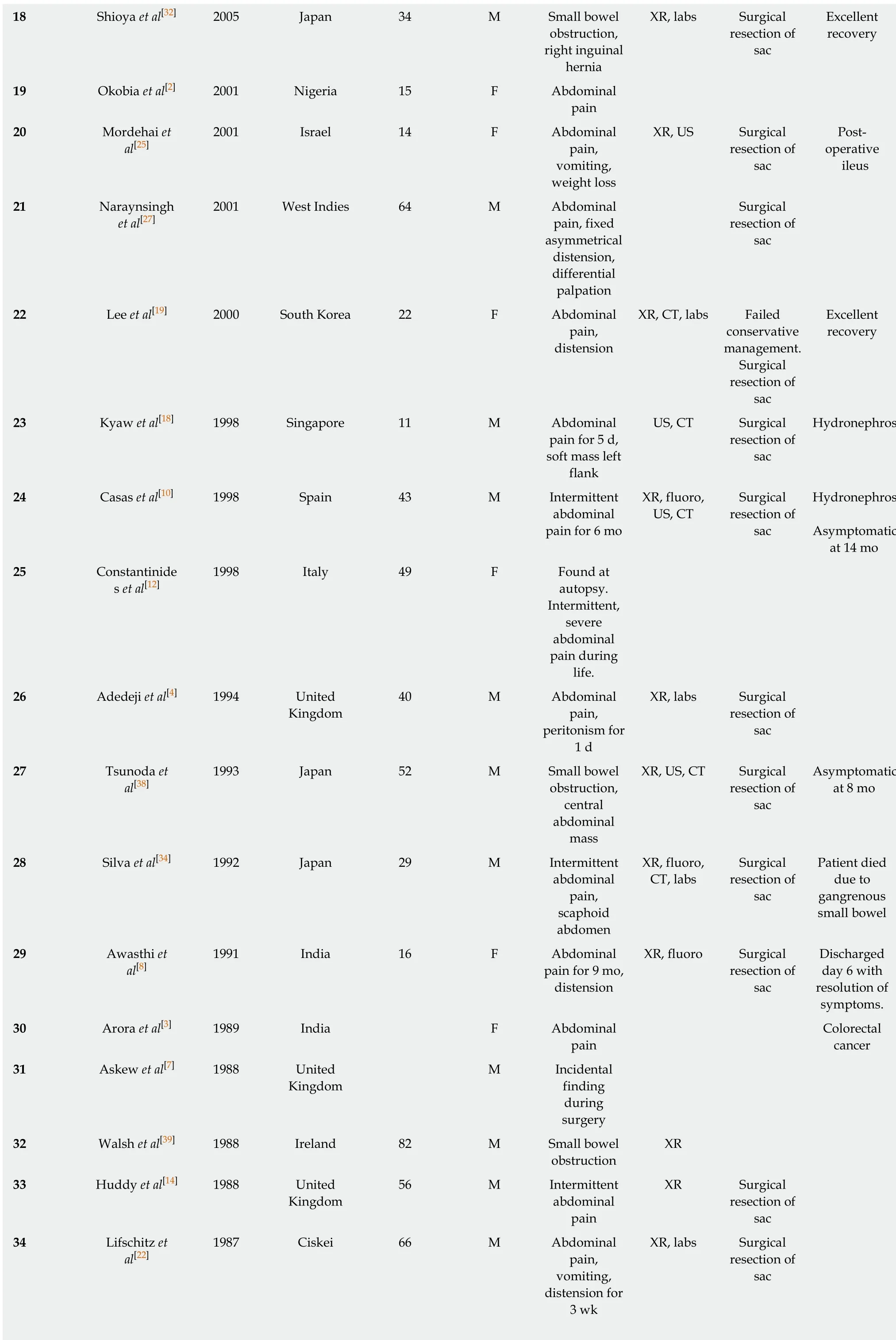

An electronic, systematic search of the literature was performed using several databases, including Medline, PubMED, Scopus and Google Scholar (Figure 1). The search was not limited by English language restriction or by date of publication. The following search terms were used as keywords: “Peritoneal Encapsulation”,“Congenital Peritoneal Encapsulation” and “Abdominal Cocoon”. The electronic search was augmented by means of manual searches of the reference lists of the selected publications. Article titles and abstracts were reviewed independently by two investigators for relevance to CPE. A significant volume of the literature reported cases of the more common abdominal cocoon or EPS, and these were excluded. Most cases of CPE could be identified and included through the abstract alone. If further clarification was required, clinical information, histopathology and photographs were used to determine cases. Full manuscripts of articles were read thoroughly and independently by two investigators, and information was extracted, including age,sex, past medical history, clinical information, diagnostic studies, management,histopathology and follow-up status. In two case reports[2,3]full articles could not be found either by contacting the journal or the relevant authors. In these cases, the abstracts alone were used to gather information. In total, 42 reports[1-42]describing 45 separate cases of CPE were found and collated. Table 1 demonstrates the key demographic and clinical information obtained from the cases.

Table 1 Patient demographics and key clinical characteristics

?

XR: X-Ray; CT: Computed tomography; US: Ultrasound scan; Fluoro: Fluoroscopic imaging; Labs: Laboratory investigations.

AETIOLOGY

The cause of CPE remains poorly understood, however it likely develops at the time the foetal mid-gut herniates into the umbilical cord at 8-10 wk gestation. The most widely accepted aetiology is attributed to Papez[28], who postulates that it is caused by an aberrant peritoneal adhesion between the linings of the physiological umbilical hernia and the caudal duodenum. Within the cord, the mid-gut is encased by peritoneum which lines the hernia walls like a sack. The neck of this sac is thus intimately adjacent to the caudal duodenum. If an adhesion forms between these peritoneal layers, significant traction forces are placed on the peritoneum which lines the mid-gut at the time the hernia is reduced. This may cause it to peel off and surround the small bowel as an extra-peritoneal accessory sac. This theory successfully explains the morphological resemblance of the membrane to peritoneum and its extra-peritoneal location.

A competing theory by Thorlakson et al[37]suggests that CPE may develop due to an abnormality in the reduction of the physiological hernia. The proximal limb of the hernia (which forms jejunum and ileum) is usually reduced first, naturally occupying the lower left of the abdomen. This causes the dorsal mesentery to be pushed to the left. Following this, the distal limb reduces and passes cranially to lie just caudal the liver. Instead, if the distal limb were to reduce first and inappropriately occupy the lower left quadrant, the proximal limb would be forced more caudally and toward the right. The distal limb would then attempt a migration toward the right iliac fossa, and in doing so its dorsal mesentery would cover the entirety of the proximal limb,thereby forming the peritoneal sac over the mid-gut. However, if this were the case, it would be expected that there would be significant mesenteric abnormalities such as mal-position and mal-rotation, which are not always associated with CPE.

Figure 1 Literature search.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Given the rarity of the condition, the incidence and prevalence of CPE is difficult to quantify. However, CPE does not appear to have any predilection toward particular ethnicities. Table 2 demonstrates the geographic distribution of cases. 42% of cases were reported from Europe, with the most common countries being United Kingdom(n = 8), Israel (n = 2)[25,29], Greece (n = 2)[24,42]and Ireland (n = 2)[1,39]. India has the second highest number of cases after the United Kingdom, with six in total[3,6,8,9,26,40]. The mean age of patients at the time of diagnosis was 40.8 (range 11-85 years). Interestingly,there is a 5:3 male predominance. The mean age of diagnosis for males and females was 46 and 32 respectively. This reflects a differential pattern of presentation between genders. Females are diagnosed earlier, with a majority presenting prior to 30 years.In contrast, males display a bi-modal age distribution, with peak presentations occurring in the 20-30 years and 60-70 year period. Medical co-morbidities of patients were documented in some reports, however it is unclear whether these are causally linked to CPE. Three patients had a diagnosis of co-morbid cancer. Two of these patients had gastro-intestinal cancer[5,16]and one of the breast[33]. One patient had an incomplete situs inversus and congenital epigastric hernia[15]and two patients had comorbid inguinal hernia[11,32].

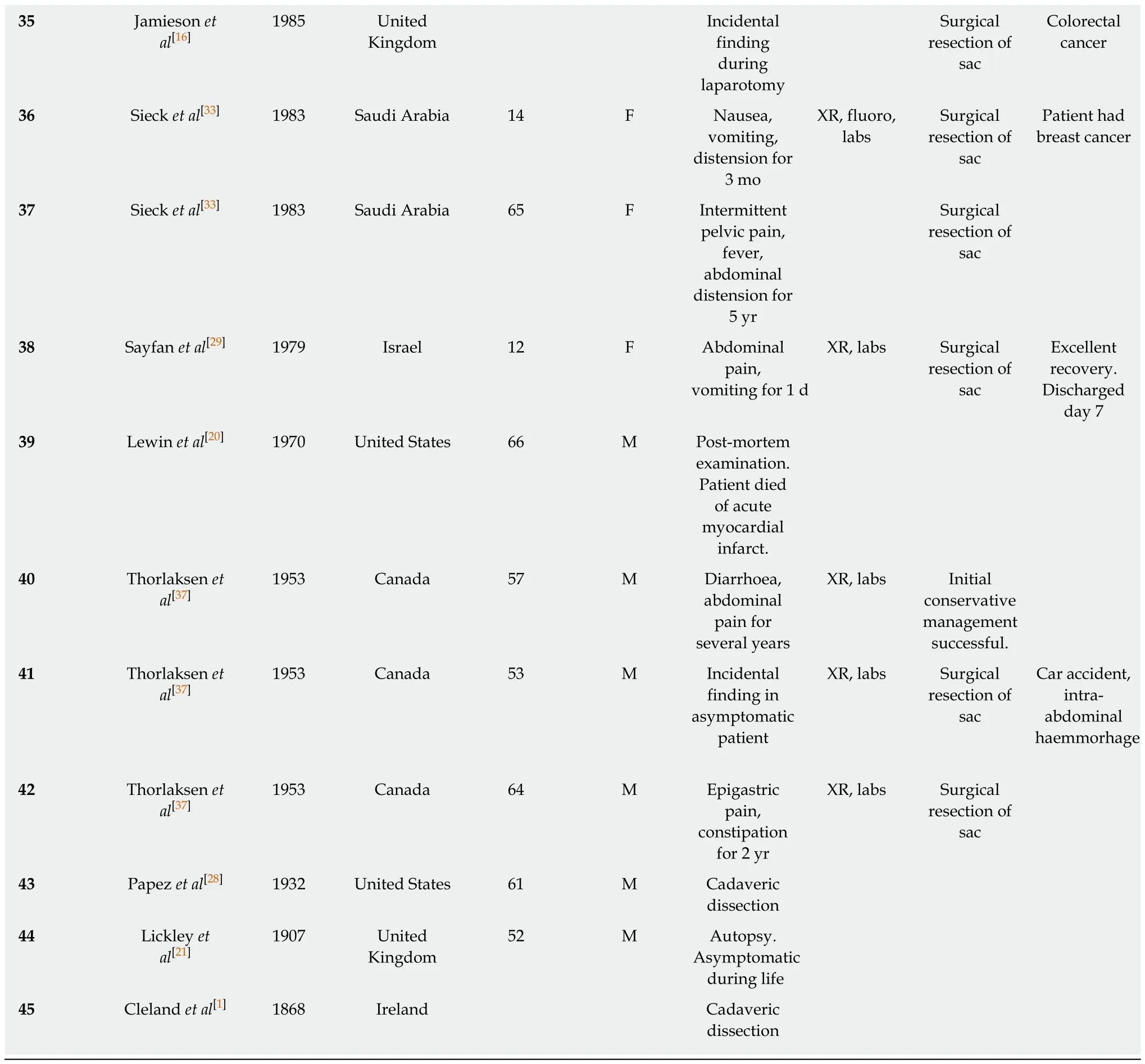

CLASSIFICATION OF ENCAPSULATING BOWEL DISEASES

Classification system

CPE is one type of a collection of conditions which are characterised by encapsulation of the bowel. We introduce a novel classification system which aims to distinguish CPE from the similar, yet discrete, conditions of abdominal cocoon and EPS (Figure 2). Abdominal cocoon and EPS were first described over 100 years ago by Owtschinnikow[43]and have been aptly reviewed by Danford et al[44]. These are acquired conditions which are characterised by a thick fibro-collagenous encasing of the small and large bowel. As such, they have a different aetiology, pathogenesis, and management to CPE. EPS describes cases of the disease that have known associations or aetiological factors, such as abdominal trauma and peritoneal dialysis. Abdominalcocoon, a term first used by Foo et al[45]in 1976, describes idiopathic cases of this disease with no known aetiological factors. We also introduce a novel, broader term,“Fibrotic Peritoneal Encapsulation (FPE)” or FPE, to denote the entire spectrum of these diseases, both primary and secondary. This term adequately describes both the morphology and histopathology of this disease, differentiating it from CPE.

Table 2 Geographical distribution of cases

Fibrotic peritoneal encapsulation

A robust discussion of FPE, both primary and secondary, is outside the scope of this review, and has been reported elsewhere[44,46-49]. However key differences between fibrotic encapsulating bowel diseases and CPE should be noted as part of forming a differential diagnosis. These are highlighted in Table 3. Firstly FPE is an acquired condition which is far more common than CPE. In most cases, there is a known secondary cause for the disease[44]. The most common of these is peritoneal dialysis[50],in which the annual incidence of FPE varies from 0.14%-2.5%[51,52]. Other causative factors include local irritant factors (abdominal trauma[53], abdominal surgery[54],peritoneal shunts[55], peritoneal tuberculosis[56], peritoneal foreign body[57], intraperitoneal chemotherapy[58]) and systemic factors (beta blocking agents[59],methotrexate[60], cirrhosis[61], Systemic Lupus Erythematosus[62], malignancy,sarcoidosis[63]). FPE is considered to be an inflammatory process, which leads to scarring and fibrosis of the peritoneal membranes through a process of cytokine and cell-mediated inflammation[64]. Furthermore, FPE tends to be significantly more symptomatic and morbid compared to CPE. Following commencement of peritoneal dialysis, an estimated 20% of patients will develop FPE at 8 years[50]. Patients tend to present with bowel obstruction, and long-standing intermittent abdominal pain. 29%of patients with FPE require emergency surgery at the time of presentation[65], and the mortality at one year is as high as 50%[66]. The morphological and histological pathology is the most definitive differentiating factor of FPE. Morphologically, FPE appears as a thick, firm, fibrotic membrane. It is separate from the peritoneum, but may have significant adhesions to the peritoneum and other surrounding structures.Histologically, FPE is characterised by dense fibro-connective tissue proliferation,chronic inflammatory cell infiltration and dilated lymphatics. This differs to CPE,which is histologically identical to peritoneum, and displays no inflammatory component.

Abdominal cocoon

Figure 2 Classification system for encapsulating bowel diseases. SLE: Systemic lupus erythematosus.

Abdominal Cocoon, also called idiopathic FPE, was first described by Foo et al[45]in 1978 as a form of FPE where no established cause can be identified. Foo's case series reported on three adolescent girls who presented with bowel obstruction and were found to have thick, fibrotic peritoneal membranes at laparotomy. Since that time,approximately 75 case reports of abdominal cocoon have been reported, and have been summarised by Akbulut[67]. The disease is most prevalent in India, China and Turkey and has no obvious gender or age distribution. Though historically abdominal cocoon was thought to affect adolescent girls, more recent studies have shown that it tends to occur mainly in equatorial areas and may be twice as common in males. It has been suggested abdominal cocoon may be caused by ‘subclinical peritonitis'[45],possibly as a result of retrograde menstruation, with a complex interplay with superimposed viral infections, salpingitis and cell mediated tissue damage[68]. This, of course, fails to explain its preponderance in males. Other studies have suggested that perhaps developmental disorders, vascular anomalies or omental hypoplasia[69]may be the basis of the disease.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical presentation

The diagnosis of CPE remains clinical, though confirmation may be obtained through diagnostic imaging and laparotomy. There is no defining gold-standard for diagnosis of CPE and this means the condition may be underdiagnosed. A proposed diagnostic algorithm is provided in Figure 3, which highlights the key clinical, radiographic and pathological features of CPE.

Symptoms associated with a presentation of CPE very likely reflect the development of an acute or sub-acute small bowel obstruction, with abdominal pain,tenderness, nausea and vomiting being the predominant clinical features. Abdominal pain is the most common cause for presentation in CPE, with 66% (n = 30) of patients reporting sudden or chronic. In these patients, 53% (n = 16) reported similar symptoms in the preceding 12 mo, usually with decreased severity. This implies that CPE may be a cause for undifferentiated, intermittent chronic abdominal pain, and diagnosis is generally delayed. Hence, CPE should be suspected in patients presenting with these symptoms. Many patients also described nausea, vomiting and constipation associated with the onset of abdominal pain. On abdominal examination,abdominal tenderness was described in 58% of patients (n = 26), usually in the periumbilical area. Peritoneal irritation (defined as one or more of involuntary guarding,rigidity or rebound tenderness) was described in 27% (n = 12) of cases. Abdominal distension was reported in 40% (n = 18) of cases, and seven cases described bowelsounds as being “high pitched”, “exaggerated: or “hyper-active”. One case described acute compression of the abdominal aorta due to CPE, resulting in extensive small bowel necrosis and death[34].

Table 3 Key differences between congenital peritoneal encapsulation and fibrotic peritoneal encapsulation

Two unique clinical features of CPE have been described, which may be more specific and aid a more prompt diagnosis. A fixed, asymmetrical distension of the abdomen was reported in 16% (n = 7) of cases. The distension was considered fixed if it was noted not to vary with peristaltic activity, and likely represents the fixed position of the bowel which is trapped within the accessory membrane. Secondly, a differential consistency of the abdominal wall to palpation has been described in several cases of CPE. It is thought that areas of the bowel which are covered by the membrane tend to be fixed, flat and firm, whilst areas which are outside of the membrane are distended and soft (as in small bowel obstruction).

In seven cases, CPE was found incidentally during surgery in asymptomatic patients. These patients were undergoing abdominal surgery for other reasons:namely, colorectal cancer[5,16], obstructive jaundice[7], right adrenal tumour[17],penetrating stab wound injury[26], tubo-ovarian abscess[33]and intra-abdominal haemorrhage[37]. Four cases of CPE were diagnosed at autopsy in patients who had no reported abdominal symptoms or complaints during life[1,20,21,28].

Imaging

Though the diagnosis of CPE remains clinical, a variety of imaging modalities may be used to aid in diagnosis. Importantly, these modalities may also screen medically unstable patients for complications of small bowel obstruction, including perforation,haemorrhage and ischemia. The use of plain X-ray has been reported in 30 cases. The majority of films showed signs of small bowel obstruction, with 56% (n = 17)reporting central, dilated loops of small bowel and 33% (n = 7) reporting air fluid levels. Two cases reported the presence of hydronephrosis[10,18]. It should be noted that 23% (n = 7) of cases reported no abnormality on plain films, and hence this modality alone cannot be reliably used to diagnose CPE. The use of contrast with X-Ray was used in 10 studies to better visualise CPE. The majority of fluoroscopic cases demonstrated non-specific features of small bowel obstruction. However, three cases demonstrated a concertina or serpentiform pattern of small bowel arrangement[26,33,36].This sign occurs when the small bowel is packed tightly on to itself in layers within the accessory sac, such that is resembles a coiled snake or concertina. This sign is more specific to CPE, and if found it should warrant further imaging.

Fifteen reports documented the use of computed tomography (CT). Only 40% (n =6) of these cases reported radiological evidence of a membranous capsule surrounding the bowel, as seen in Figure 4. Hence, CT scanning may not have the resolution to visualise the accessory sac in all cases, and should remain only an adjunct to a clinical diagnosis. Other features commonly reported in CT scans include dilated loops of bowel in 46% of cases (n = 7), and fluid collection in 12% of cases (n =2). Mitrousias et al[24]described a novel helical pattern of small bowel within the membranous sac on 3D volume rendered imaging. Ultrasonography has also been used in nine cases, of which four reported no significant abnormalities. Other findings included small bowel dilation, ascites[25], hydronephrosis[10]and gall bladder distension[9].

It is clear that imaging is neither sensitive nor specific in identifying cases of CPE. It should therefore be used only as an adjunct to aid in the diagnosis of CPE. Imaging does, however, maintain an important role in determining the presence and severity of complications in medically unwell patients, such as acute bowel obstruction,perforation, ischaemia and bleeding.

Laboratory investigations

No specific laboratory studies exist for aiding in the diagnosis of CPE. Routine blood tests were reported in 13 studies. In six of these, leucocytosis or raised inflammatory markers were noted. In the remaining seven cases, all blood tests were within normal ranges.

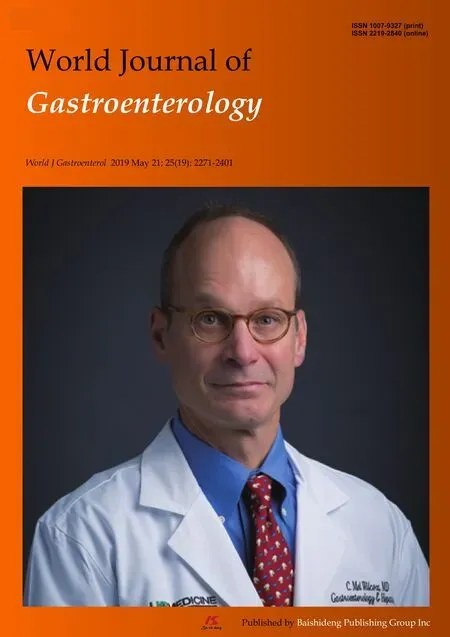

ANATOMICAL PATHOLOGY

A majority of CPE cases are diagnosed at the time of direct visual inspection during diagnostic laparotomy or laparoscopy, as seen in Figure 5. 69% (n = 31) of cases described the accessory sac in CPE as morphologically similar to that of peritoneum.This is consistent with Papez's theory of CPE as an accessory peritoneal membrane derived from the umbilical hernia. The membrane is typically semi-transparent,vascularised and thin. This contrasts markedly with the thick, white, fibrotic capsule in FPE. The extent of encapsulation of the small bowel in CPE was reported in most cases. 25 cases reported the sac encasing the entirety of the small bowel. The sac typically starts at the duodeno-jujenal junction, to a point within approximately 10-40 cm of the ileo-caecal junction. Four cases described the accessory sac as covering only a small part of the ileum. In cases of small bowel obstruction, the transition point was typically found at the proximal opening of the accessory membrane.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

Histopathology was reported in only 14 of the 42 cases. Four of these cases reported histopathological findings consistent with normal peritoneal tissue. In two of these reports, there were features suggestive of active inflammation. Fibrosis (n = 2), fibrous tissue (n = 3), fibro-connective tissue (n = 1) and fibrovascular tissue (n = 1) were reported in 7 cases. Two of these cases also reported the presence of mesothelial cells.The remaining histopathological reports included non-specific chronic inflammatory changes, membranous and elastic bundles and an isolated report of mesothelium.

MANAGEMENT AND PROGNOSIS

Treatment of CPE can be conservative, medical or surgical. Conservative management has only been described in a single case of CPE, which was asymptomatic and diagnosed incidentally on routine imaging. The patient remained well and required no further medical management. Medical management generally involves the resuscitation, stabilisation and treatment of the unstable patient with CPE. This is likely due to acute small bowel obstruction and the potential complications associated with this, including perforation, ischaemia, necrosis and haemorrhage. A majority of patients that were hospitalised with CPE were fasted and received nasogastric decompression, intravenous fluid therapy, intravenous anti-biotics and intravenous proton pump inhibitors.

Surgical management consists of exploratory laparotomy, peritonectomy, adhesiolysis and enterolysis. Excision of the sac is usually performed from along its attachments proximally and distally. This has generally been described as a straightforward procedure, devoid of major intra-operative hazards, likely because the accessory sac is extra-peritoneal. Most importantly, adhesions at the neck of the sac must be carefully resected to ensure complete release of the bowel and prevent bowel obstruction and ischaemia post-operatively. In our experience[23], the most difficult part of the procedure is at the time of releasing the proximal neck of the sac.It may lie adjacent to the duodeno-jejunal flexure, and is hence in close proximity to the superior mesenteric vasculature. Care should be taken in this step to ensure the vessels remain undamaged, whilst ensuring complete resection o the sac and any associated adhesions.

Prognosis following prompt surgical management of CPE is excellent. 14 cases reported excellent post-operative recovery with no complications. Length of hospital stay was recorded in 8 cases, with an average of 13 d, and a range of 6-33 d. Very few papers have reported on long term follow up of patients, with the longest being 7 years of symptom free survival[9]. Two patients died during the initial hospital admission: One patient died due to sepsis secondary to a chest infection[31], and the other died due to extensive bowel necrosis[34]. This latter patient was noted to have extensive gangrenous small bowel at the time of initial laparotomy, presumably due to acute bowel obstruction and compression of the abdominal aorta. On re-look laparotomy after 24 h, the patient went into cardiac arrest and died. Other complications that have been reported with CPE include post-operative ileus[25], bowel obstruction secondary to adhesions[41], biliary fistula[37]and duodenal ulceration requiring resection[37].

CONCLUSION

Figure 5 Accessory peritoneal membrane, with attachment to posterior body wall (arrow).

CPE is a very rare, congenital condition which has been described in less than fifty cases in the literature. For this reason, it remains poorly understood, underdiagnosed and mismanaged. It is an important consideration in patients with long-standing,undifferentiated, intermittent abdominal pain, and these patients should be investigated appropriately. More rarely, patients can develop acute bowel obstruction due to CPE, and warrant hospitalisation, medical stabilisation and emergency surgical procedures. The diagnosis remains clinical, with several unique clinical findings of CPE including a fixed, asymmetrical abdomen being specific indicators of the disease.Adjuncts such as plain imaging, fluoroscopy, CT scanning and ultrasound may also be used in conjunction to aid in diagnosis. Ultimately, most patients undergo diagnostic laparotomy and excision of the accessory peritoneal layer, which results in an excellent prognosis. It is yet unclear what causes CPE, and further work is required to elucidate this as it may provide insights in better identifying patients at risk, and treating them accordingly.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2019年19期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2019年19期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Cyst fluid glucose: An alternative to carcinoembryonic antigen for pancreatic mucinous cysts

- Mechanisms of hepatocellular carcinoma progression

- Autoimmune hepatitis and IgG4-related disease

- Electroacupuncture at ST36 modulates gastric motility via vagovagal and sympathetic reflexes in rats

- Role of D2 gastrectomy in gastric cancer with clinical para-aortic lymph node metastasis

- Risk factors for progression to acute-on-chronic liver failure during severe acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis Β virus infection