Pancreatic cancer screening in patients with presumed branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms

Yuichi Torisu, Kazuki Takakura, Yuji Kinoshita, Yoichi Tomita, Masanori Nakano, Masayuki Saruta

Abstract

Key words: Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm; Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma;Endoscopic ultrasonography; Screening; Early diagnosis

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) persists worldwide as a remarkably lethal malignancy with extremely poor prognosis. The National Cancer Center Japan estimated that 39800 Japanese individuals developed PDAC in 2017, with 34100 among them having died; likewise, the 5-year survival rate for Japanese PDAC patients was only 7.8%. One of major causes of poor prognosis for PDAC is the generally delayed diagnosis, which results in over 90% of diagnoses being made at stages III or IV[1]. Egawaet al[2]reported the 5-year survival rates of PDAC according to the UICC International Union Against Cancer stages (6thedition) as 68.7% for stage IA, 59.7% for IB, 30.2% for IIA, 13.3% for IIB, 4.7% for III, and 2.7% for IV. This pattern of steady decline in survival suggests that even if patients with PDAC were to be diagnosed in the earliest stage (I), the prognostic outcomes would still be remarkably poor.

On the contrary, it was reported that the 5-year survival rate for early PDAC of size 10 mm or less was relatively good, at 80.4%; although the detection of such a small size PDAC could be made in up to only 0.8% of the total patient population. The range of challenges to small PDAC detection encompass patient-related features (e.g.,asymptomatic presentation) and clinic-related limitations (e.g., lack of established screening guidelines and the limits of visualization in ultrasonography (US),commonly used to observe the whole pancreas in screening). Therefore, periodic screening is recommended for patients with PDAC, especially those identified as high-risk - such as patients with PDAC family history, diabetes mellitus, or chronic pancreatitis[3-6].

Pancreatic cysts, including the intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs),are another risk factor for PDAC[7-9]. Hence, proper identification of affected patients and steady follow-up with routine imaging examinations will likely improve early detection rates and, consequently, prognosis of PDAC. Unfortunately, there remains a lack of coalesced knowledge on IPMN case management for PDAC. This review aimed to provide an informational foundation for a proper screening strategy for follow-up of IPMN cases, for IPMN-concomitant PDAC.

PREVALENCE OF PANCREATIC CYSTS

With the recent advancements in diagnostic imaging technologies involving magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the frequency of incidental detection of pancreatic cystic lesions has increased[10]. Moreover, the minimum size for detection of a pancreatic cyst has decreased, with solitary cysts of only a few millimeters in size being identifiable[10].

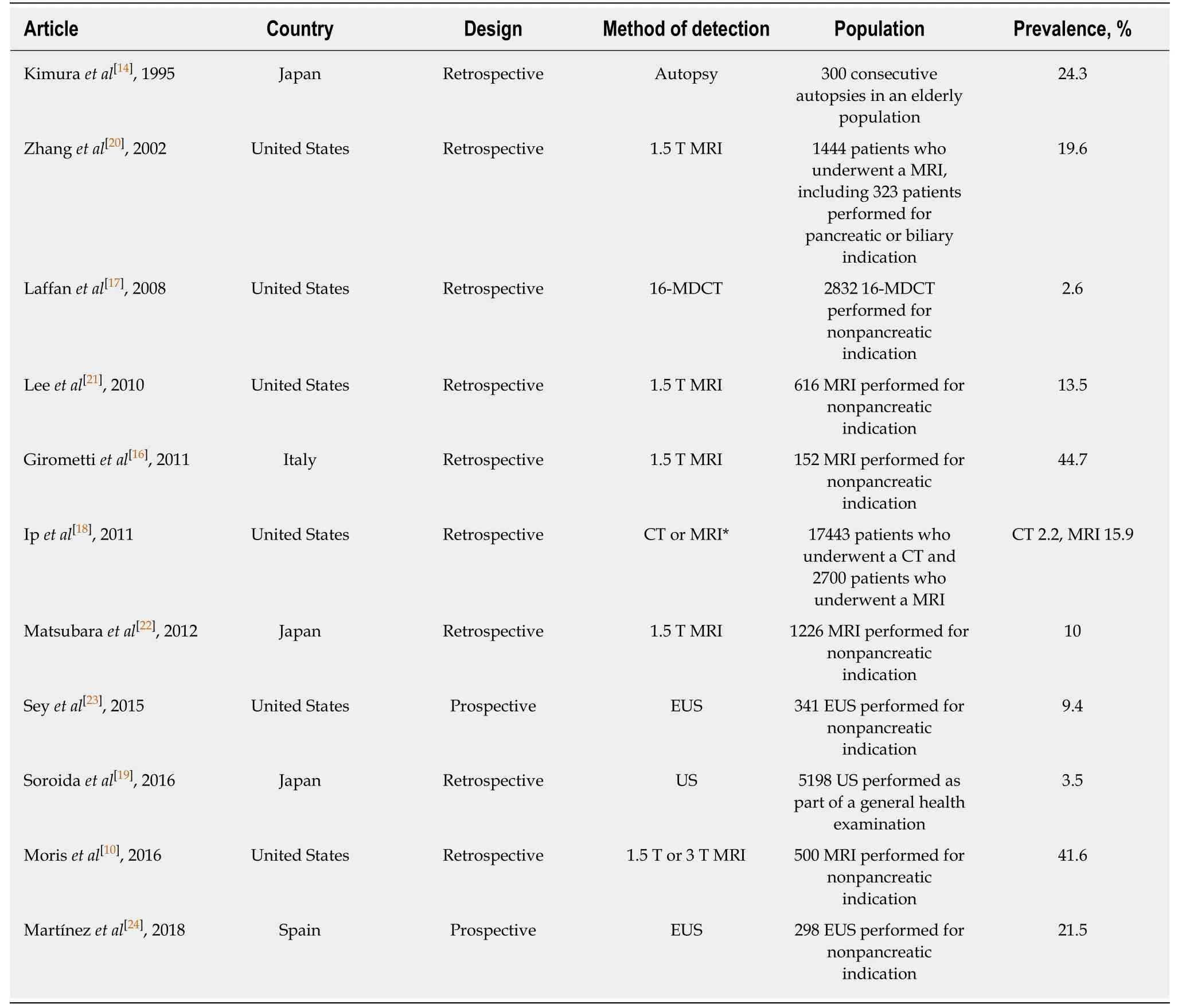

The previous studies on the prevalence of incidental pancreatic cyst are summarized in Table 1. Pancreatic cysts belong to a heterogeneous group of tumors,ranging from benign to malignant[11]. The latter includes the precursor lesions of PDAC, such as the IPMNs and mucinous cystic neoplasms[12]. The IPMNs are further subdivided according to location in the ducts. The 2017 revised international guidelines[13]distinguished IPMNs in the main duct from those in the branch ducts.Specifically, the branch-duct (BD)-IPMN was defined as located in the branch duct with dilation, having > 5 mm cyst size, and interacting with the main pancreatic duct.

An investigation by Kimuraet al[14]of the epithelial growth of small cystic lesions in 300 consecutive autopsy cases found cystic lesions in 24.3% (n= 73). Histological analysis identified 47.5% as normal epithelium, 32.8% as papillary hyperplasiawithout atypia, 16.4% as atypical hyperplasia, and 3.4% as carcinomain situ.Apparently, the cystic lesions without normal epithelium were equivalent to IPMN. In addition, Fernández-del Castilloet al[15]reported that most pancreatic cysts are mucinous cystic tumors (including IPMNs), and Giromettiet al[16]found that 70.6% of the detected pancreatic cysts presented IPMN-like patterns (i.e., polycystic, main pancreatic duct interaction, and > 5 mm) or an indeterminate pattern. Considering these collective data, it seems that the majority of pancreatic cysts are actually representatives of IPMNs.

Table 1 Previous studies on prevalence of incidental pancreatic cysts

The reported prevalence rates for pancreatic cysts have varied depending on the imaging method used for detection. Namely, the reported detection rates have been for 2.2%-2.6%[17,18]for computed tomography (CT), 3.5%[19]for US, 10%-44.7%[10,16,18,20-22]for MRI, and 9.4%-21.5%[23,24]for endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). A similar amount of reports[10,14,16,17,19-21,23,24]have demonstrated aging as a significant risk factor for pancreatic cysts; in general, the frequency of pancreatic cysts among the elderly is over 20%.

PDAC CONCOMITANT WITH IPMN

Definitions of PDAC concomitant with IPMN and PDAC derived from IPMN

Unlike the PDAC derived from IPMN, PDAC occurring concomitantly with IPMN features PDAC and IPMN that developed from different parts of the pancreatic parenchyma. It has been suggested that these two forms of PDAC - that derived from IPMN and that concomitant with IPMN - should be considered as different diseases[25]. However, in the case of PDAC having developed from tissue adjacent to the IPMN, the distinction between PDAC derived from IPMN and PDAC concomitant with IPMN will be difficult. Molecular biomarkers, including the expression profile of MUC and the mutational status of GNAS and KRAS, may help to distinguish these two types of PDAC more clearly[26,27].

Assessment of concomitant PDAC in surgically resected IPMN

There have been several studies for PDAC concomitant with IPMN since the first report in 2002 by Yamaguchiet al[28]. The reported incidence rates of PDAC concomitant with IPMN are 9%[28]and 4%[29], determined in two studies of surgically resected IPMN case series. Ingkakulet al[30]found that 9.3% (n= 22) of patients with IPMN (n= 236) had concomitant PDAC, either synchronously or metachronously. In addition, Yamaguchiet al[25]found 31 cases of PDAC concomitant with IPMN among 765 IPMN resections. However, it seems that these results might represent underestimations of the actual number of cases of PDAC concomitant with IPMN because of the study design used (i.e., retrospective evaluation of surgically resected specimens).

Conversely, Matsubaraet al[22]reported that, among a total of 116 PDAC patients, 65(56%) presented with both PDAC and pancreatic cysts. Moreover, 5 presented with cystic lesions (identified at least 2 year before the PDAC diagnosis) located upstream of the PDAC and 28 with lesions downstream of the PDAC. These 33 cases with pancreatic cystic lesions were classified as “preexisting” PDAC, and accounted for 28% of the total 116 patients evaluated. Accordingly, the actual frequency of PDAC concomitant with IPMN might be higher than the rates reported to date.

Frequency of PDAC concomitant with IPMN among patients with BD-IPMNs

The previous studies that have examined the duration of concomitant PDAC development during the follow-up period for IPMNs are summarized in Table 2[7-9,31-37]. Interestingly, the incidence of PDAC concomitant with IPMN tends to be higher in Japan (about 1% per year[7,8]), as compared to the reports from the United States and Italy. One of the Japanese studies, by Tannoet al[8], investigated 89 BDIPMN patients without any mural nodule and followed each up for at least 2 year(median: 64 mo; range: 25-158 mo), and identified 4 cases of PDACs located distant from the BD-IPMN in 552 patient-years of follow-up (7.2 per 1000 patient-years).

Another Japanese study, by Maguchiet al[9], analyzed 349 follow-up BD-IPMN patients who had no mural nodules on EUS exam at initial diagnosis, and identified 7(2.0%) concomitant PDAC cases within the follow-up period (median: 3.7 year;range: 1-16.3 year). Likewise, Kamataet al[36]showed a 6.9% incidence of concomitant PDAC development in 102 BD-IPMN patients without mural nodule during the follow-up period (median: 42 mo). Finally, Ueharaet al[7]found a 1.1% per year incidence of PDAC among patients with BD-IPMN, whereas the expected incidence of PDAC in the age- and gender-matched control group was calculated to be 0.045% per year.

Taken together, the frequency of concomitant PDAC in Japanese patients with BDIPMNs is not low, suggesting that these patients should be considered for a screening strategy, particularly examining the whole pancreas.

Characteristics of PDAC concomitant with IPMN

As described above, screenings for patients with IPMN should be conducted not only to monitor the primary IPMN lesions but also to track the possible development of concomitant PDAC. However, due to the large number of IPMN patients, it will be important to limit the surveillance target population and to decide on the appropriate screening interval for the imaging examinations. Understanding the distinctive characteristics of PDAC concomitant with IPMN may be helpful for determining the optimal detection parameters of PDAC.

Tannoet al[8]reported that the incidence of PDACs located distant from the BDIPMNs was significantly higher for older patients (> 70 year) and for women. Idenoet al[26,28]showed that distinct PDACs frequently develop in the pancreas presenting benign gastric-type IPMN without GNAS mutations. In addition, it had been reported that IPMN patients with a family history of PDAC are at higher risk of developing PDAC concomitant with IPMN. A study by Nehraet al[39]of 324 patients with resected IPMNs revealed that patients with a family history of PDAC developed concomitant PDAC more frequently than did those without (11.1%vs2.9%,P= 0.002). Likewise, a study of 300 patients with IPMN by Mandaiet al[40]revealed that concomitant PDAC occurred more frequently in patients with affected first-degree relatives than in those without (17.6%vs2.1%,P= 0.01). Thus, individuals with the above characteristicshave a higher risk of PDAC and should be checked more attentively for early detection of concomitant PDAC.

Collective studies have shown that malignancy of primary IPMNs does not correlate with incidence of concomitant PDAC. Tadaet al[32]reported that IPMNs with concomitant PDAC found in cases with small cyst diameter are probably indicative of benign IPMNs. Also, Ingkakulet al[30]reported that, in their study population, all of the detected concomitant PDAC cases involved patients with BD-IPMN or BD-IPM adenoma. The current IPMN guidelines[13,41]describe surveillance strategies for PDAC derived from IPMN and state that the smaller the size of the IPMN, the longer the interval between screening examinations. In addition, the American Gastroenterological Association guidelines[41]recommend canceling the follow-up if there are no changes within 5 year; although, Mandaiet al[40]reported that 6 of 9 concomitant PDAC cases were detected at 6 year or later after the detection of IPMN.Thus, a more cautious screening strategy may be essential for early detection of concomitant PDAC in the patients with BD-IPMN.

Imaging modalities for early detection of PDAC concomitant with BD-IPMN

In recent years, several imaging modalities have been applied in surveillance of BDIPMN; these include US, CT, MRI and EUS. However, it is still unclear which of these imaging modalities should be selected for screening and what the optimal length of interval is for each in follow-up, to best achieve early detection of both IPMN-derived and -concomitant PDAC. As described above, while current guidelines[13,41]mention surveillance strategies for PDAC derived from IPMN, these remarks are,unfortunately, irrelevant for the early detection of IPMN-concomitant PDAC.

Kannoet al[42]retrospectively analyzed 200 PDAC cases of stage 0 and stage I, and identified the dilated main pancreatic duct as an indirect imaging feature of early PDAC - detectable to a similar degree in all imaging modalities: 74.8% in US, 79.6% in CT, 82.7% in MRI, and 88.4% in EUS. In contrast, direct imaging features of early PDAC could be seen most clearly in EUS (76.3%) compared with the others (52.6% in US, 51.5% in CT, and 45.1% in MRI). Kamataet al[36]reported that among the 102 BDIPMN patients without mural nodule, who were followed-up with image diagnosis every 3 mo (by EUS semiannually and by US/CT and MRI annually, performed respectively between the two EUS examinations), 7(6.9%) developed concomitant PDAC, with an average diameter of 16 mm (range: 7-30 mm) during the follow-up period (median: 42 mo; range, 12-74 mo). The study also determined that EUS was the only imaging modality capable of detecting concomitant PDAC at a curable stage; the detection rates of PDAC concomitant with IPMN during the follow-up period were 100% by EUS, 0% by US, 43% by CT and 43% by MRI.

Although EUS was demonstrated to be superior in detecting PDAC concomitant with IPMN, another previous study demonstrated that EUS does not have marginal use in surveillance of BD-IPMNs[43]. In particular, the statistical associations of EUS with different rates of morphologic progression, surgery, malignancy and death all fell below the threshold of significance. However, the meta-analysis had some limitations in the study design that may have impacted the results - namely, that most included articles reported on retrospective studies and that several of the studies included data from patients who were followed up with EUS at long intervals.

Hopefully, future prospective studies will be conducted to confirm the usefulness of EUS in surveillance of patients with IPMNs for potential development of concomitant PDAC. Furthermore, these studies are necessary to determine the optimal surveillance strategy (intervals and imaging modalities) for BD-IPMN patients in particular. As this is an ongoing unresolved health issue, impacting populations across the globe, there is urgency to performing such studies.

CONCLUSION

Appropriate retainment of patients with IPMNs, especially those with BD-IPMNs, for periodic screening with routine imaging examinations, particularly EUS, will help to promote early detection and better prognosis of both IPMN-derived and -concomitant PDAC. To this end, further evaluations are needed to confirm the most efficient surveillance strategies for presumed BD-IPMN.

World Journal of Clinical Oncology2019年2期

World Journal of Clinical Oncology2019年2期

- World Journal of Clinical Oncology的其它文章

- Rational-emotive behavioral intervention helped patients with cancer and their caregivers to manage psychological distress and anxiety symptoms

- Hong Kong female’s breast cancer awareness measure: Crosssectional survey

- Impact of conditioning regimen on peripheral blood hematopoietic cell transplant

- Retrospective evaluation of FOLFlRl3 alone or in combination with bevacizumab or aflibercept in metastatic colorectal cancer

- Existing anti-angiogenic therapeutic strategies for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer progressing following first-line bevacizumab-based therapy

- Oligometastases in prostate cancer: Ablative treatment