Implications of the Funding Crunch

By Gao Zhanjun

I n June 2013, there was a rare “money shortage” in China’s financial market:the repo rate reached a record high of 30%, bond issues failed and yields rose sharply.Massive fund redemptions followed,straining the market infrastructure.Some institutions defaulted and the stock market plummeted.

Money shortages – dangerous and sometimes surprising in their severity – are not necessarily a thing of the past. Some – though not all – of the contributing factors are still with us today. The fact that various factors were intertwined and appeared together at a sensitive time made this cash crunch one of the most complex events in China's financial history.

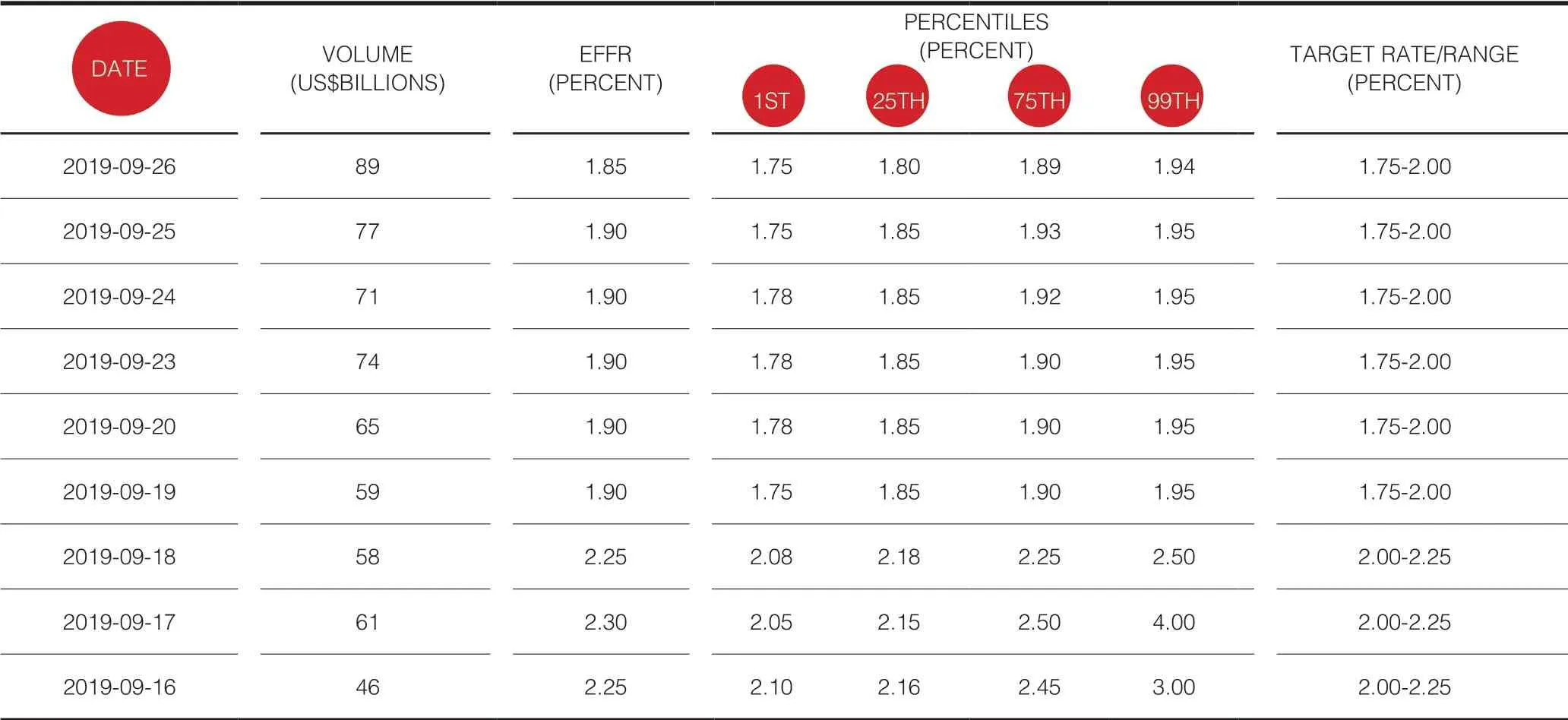

More recently, the US had its own taste of a money shortage. On September 16, 2019 the effective federal funds rate, or EFFR, suddenly surged. (The federal funds rate is the interest rate at which depository institutions lend balances at the Federal Reserve to other depository institutions overnight.) The weighted average rate rose from the previous session’s 2.15% to 2.25%. That reached the upper limit of the federal funds target rate (FFTR) range of 2-2.25% and exceeded 3% at its peak.The next day, the EFFR continued to rise, with the weighted average rate reaching 2.3%, again breaking the upper end of the FFTR range and briefly exceeding 4%. (See Chart 1)The repo rate, meanwhile, shot up to a dangerous 10%, a highly unusual level. This was an American funding crunch.

What might be behind this kind of money market volatility? What are the implications and what remedies are available to policy makers?

Chart 1 EFFR exceeds the upper limit of the policy rate range

Financial disintermediation is one of the main contributors. It is an inevitable stage in the development of a multi-tiered capital market as well as the promotion of financial deepening and interest rate liberalization. The US completed this process in the 1990s and brought about a complete transformation of the financial sector. In recent years, the pace of China's financial disintermediation has been very fast,and this has led to significant changes in the structure of financial assets.

But every coin has two sides.Financial disintermediation can be good, and it is important to make a sober assessment of its possible impact. In a column titled “Financial Disintermediation Alarm” in Caixin Weekly in April 2012, I made an analysis, in which I specifically mentioned that it would “lead to the normalization of liquidity tightness,”and abnormal conditions would occur under certain conditions.

The “money shortage” that occurred in China in June 2013 created lingering fears. But we should not forget that despite the different contributing factors and severity of the problems, money shortages are not uncommon in history.

One can see the present better by looking at the past. What happened in 2011 is another example. The sevenday repo rate peaked at 10% in June of that year and remained at 7% in December. The bill's direct interest rate reached 13% in September. Many of the traditional institutions which used to provide a lot of money to the market were suddenly in need of funds.

Sometimes, at times of great market pressure, some previously sound institutions implode.

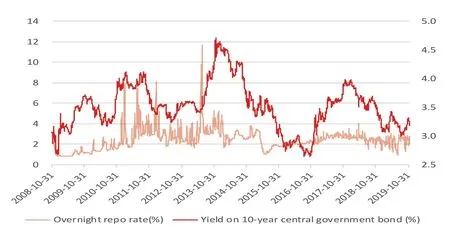

Chart 2 China's money market volatility

What is the explanation for this?The data show that the central bank's liquidity withdrawal was very limited,and its liquidity offsetting ratio was as low as it was in 2009 when the liquidity was generally loose. So, the monetary authorities’ open market operations can be ruled out as the root cause.

In my opinion, the tight policy tone that began in 2011 as well as strengthened macro-prudential supervision and concentrated disclosure of credit risks were contributors to tight liquidity. But the explosion of wealth management products was the main reason. In that year, the circulation of various wealth management products nearly doubled. The balance rose from 5.5 trillion yuan to 9 trillion yuan. Such products have the natural characteristics of credit intermediation, term restructuring and liquidity conversion, as well as the use of some leverage and the exploitation of regulatory gaps.The rapid expansion also sped the movement of capital across the balance sheet, from the supply side as well as the demand side. This naturally increased volatility.

Going back to the end of 2010,there was another period of money shortages. A number of institutions lacked funds and defaulted. This phenomenon continued until the 2011 Spring Festival.

There are earlier examples as well.In 2007, as the stock market soared and drew funds from the banking system, a large amount of money was put into wealth management products that could be used to buy stock in new share offers. This resulted in a spike in short-term interest rates and a situation of “loose macro liquidity and tight micro liquidity.” At that time,financial disintermediation was not obvious, and the balance of wealth management product and trust assets was only 1,336 billion yuan. Although the background factors were different and the financial stresses were limited to a few areas, financial disintermediation began to show up.

Now let’s look at the situation in June 2013, when repo rates hit the 30% level and bonds were sold off.(See Chart 2)

This was largely a cash crunch.The reasons included gambling on the balance between thedemand and supply of capital and regulatory storms that changed the familiar rules of the game.However, there is no doubt that financial disintermediation, wealth management products and shadow banking played a part. Most of the discussions about high leverage ratios, inter-bank business expansion and off-balance sheet business were related to this.

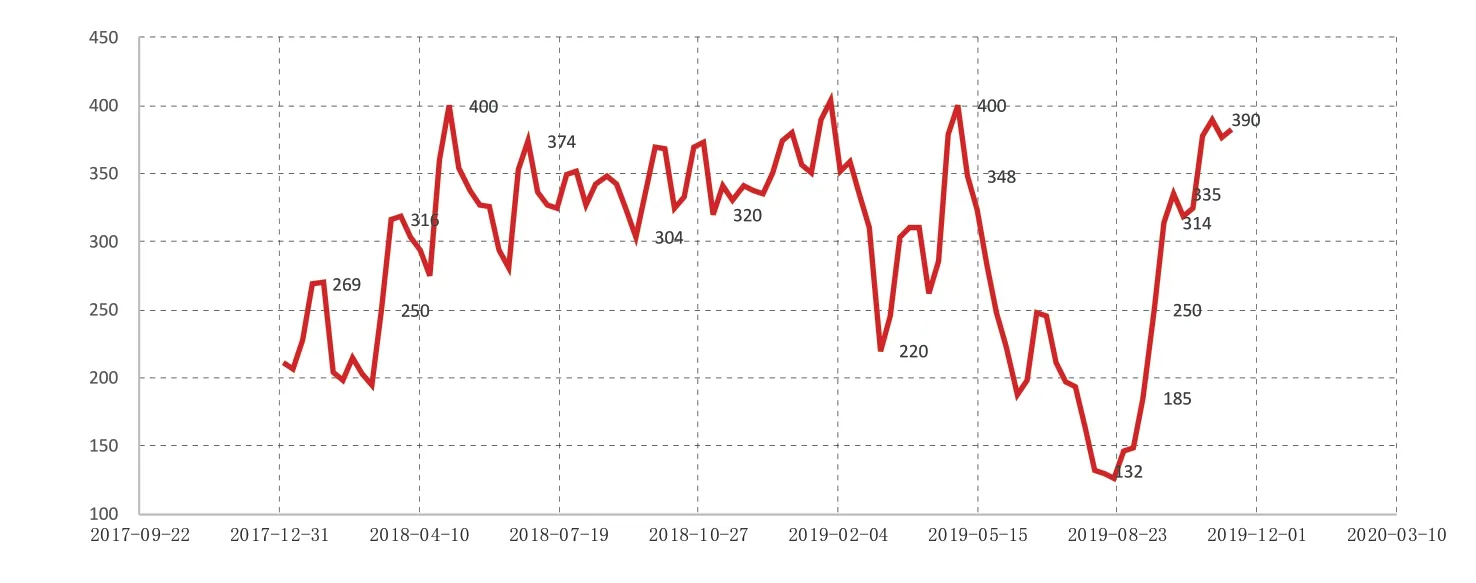

Chart 3 Operations taken to relieve the cash shortage

However, from the rare direct linkage between the money, bond and stock markets, it is clear this was actually more than a “money shortage.” It was in fact a financial shock caused by more complex factors that had a knock-on effect -what I call the “June shock.”

Imagine this: if the funding situation in June 2013 had been more normal, would the stock market have slid on the Fed's desire to quit easing combined with the continued weakness in China's economic data and the potential financial risks?And add to that the insistence on not introducing stimulus measures at the time – would that have been enough to trigger a stock sell-off? Probably,yes! So, the “June storm” was not only a “money shortage.” The “money shortage” was just the visible part of the phenomenon.

It is not hard to see that this round of financial turmoil was actually a global phenomenon and not unique to China. When then-US Federal Reserve chief Ben Bernanke testified to Congress in May of 2013, he gave the first hint of winding down quantitative easing, causing global stock and bond markets to fall – and that was especially pronounced in Japan. Chinese stocks also opened lower, with losses magnified after May 31. At a June 19 press conference,Bernanke made a surprise reference to tapering the existing super loose monetary policy and ultimately ending it. Global equity markets plunged again, bond yields surged and the dollar strengthened.

Market expectations were also hit by weak fundamentals in the Chinese economy, rising debt burdens and emerging potential financial risks.Despite disappointing economic data in the first quarter of 2013, the market had expected the second quarter to improve. April data were another negative surprise and the May data blew away any remaining confidence.Doubts about the authenticity of the import and export figures added to the uncertainty.

At the same time, there were signs that China was not ready for a new stimulus.

These factors were the direct cause of the sharp drop in China’s stock market in June of that year and the outflow of foreign capital. The impact was magnified by the shortage of money.

Overall, various factors were intertwined just at that sensitive time. The “June storm” became one of the most complex events in China's financial history. Financial disintermediation is the main cause of a “money shortage.” But the “June storm” was a chain reaction caused by a variety of factors and it was a reminder that in today’s increasingly complex economic and financial world, both market and policy levels require caution, preparation and a careful response. Some people think that the “June storm” was the beginning of China’s financial crisis.Although there were problems, proper reflection can help our understanding and point to the right direction to reduce hidden risks.

Chart 4 the U.S. Treasury General Account

Chart 5 Drivers of banks’ lowest comfortable level of reserves (LCLoR)

We still have a problem with disintermediation, though there are substantial differences between now and then. Now, regulators and financial institutions have been more prepared to prevent another 2013-like money shortage. But the issue is:because of the financial deregulation and liberalization, because of disintermediation, since June 2013, the size of China’s leverage– the shadow-banking system,has increased dramatically, with enormous risky lending practices taking place. In order to work around rules of lending, evade capital and provisioning requirements, some smaller commercial banks exposed themselves to a much wider spectrum of risk. In May 2019, regulators assumed control of Baoshang Bank Co. for one year citing “serious”credit risks, which became China’s first bank seizure since 1998.Baoshang is a small city-commercial lender that obscured its exposure to risky borrowers by tapping into the shadow-banking system. China Construction Bank Corp., one of the nation’s largest lenders, was brought in to manage Baoshang’s business while it’s under government control.Though the seizure of Baoshang was an isolated incident, it led to a sharp rise in repo rates and borrowing costs for smaller banks and nonbank institutions immediately after the seizure.

The American Funding Crunch

On September 17 of this year,the rate on the overnight general collateral repo in the US jumped to 10%, about four times its normal level. The New York Fed stepped in for the first time since the 2008 financial crisis, releasing $53 billion in overnight financing. Three days of operations followed, raising the amount of overnight funds to $75 billion a day. On September 20, the New York Fed announced that it would roll out $75 billion in overnight funds every day from September 23 until October 10, with three 14-day repurchase agreements of at least $30 billion each. (See Chart 3) In October,the operations continued with an expanded scope.

Markets had fully anticipated the September 18 rate cut by the Federal Open Market Committee, which determines the appropriate stance of US monetary policy. However,money was tight and interest rates surprisingly shot up that week,putting Federal Reserve Board Chair Jerome Powell in an awkward position. This suggests that the Fed had lost effective control over shortterm interest rates. The reason for the rise in interest rates has been widely debated. In my opinion, it was probably the combination of the following several factors that led to the funding crunch.

Paying Taxes

Firstly, companies pay taxes and the deadline for quarterly federal taxes was approaching. Money went into the Treasury General Account, or TGA – an account the Federal Reserve provides to the US Treasury which,similar to a checking account, allows Treasury to deposit or withdraw cash every day. (See Chart 4) This reduced the amount of reserves in the banking system.

Treasury Contributions

Secondly, for some time, Treasury sales had soared along with the growth in the US budget deficit. Net issuance reached US$1.3 trillion in 2018 and will hit US$1.2 trillion in 2019, double the amount of 2017.That would reduce the size of reserves in the banking system. When a large number of Treasury bonds are issued at about the same time, reserves in the banking system are withdrawn once investors make payments and funds are diverted to the TGA. (See Chart 4) September 16 was the settlement date for the $78 billion of bonds outstanding.

This has happened many times before. According to the 2008 open market operations annual report of the New York Fed, the overnight repo rate exceeded the upper limit of the FFTR range by 10 basis points in December 2018 due to the increased supply of treasury bonds. On the last trading day of the year, the overnight repo rate rose sharply by 50 basis points due to massive clearing of treasuries and a huge increase in dealers' inventories, combined with a typical year-end balance sheet management effect.

Regulatory Impact

Thirdly, the banking system's regulatory requirements require higher liquidity provisions and trading margins, making it more expensive to lend money and make markets. This has left capital markets far less strong than they used to be. A sample survey conducted by the Federal Reserve in February 2019 showed that a whopping 63%of banks believed that meeting the internal liquidity stress test had significantly increased their need for capital provision. (See Chart 5)

Due to the high dependence of non-bank financial institutions on the repo market, once these institutions were unable to borrow money from the banking system, liquidity became tight and interest rates rose.September is the end of the quarter,and financial institutions were pulling out funds to meet targets such as capital adequacy. That drained liquidity from the system.

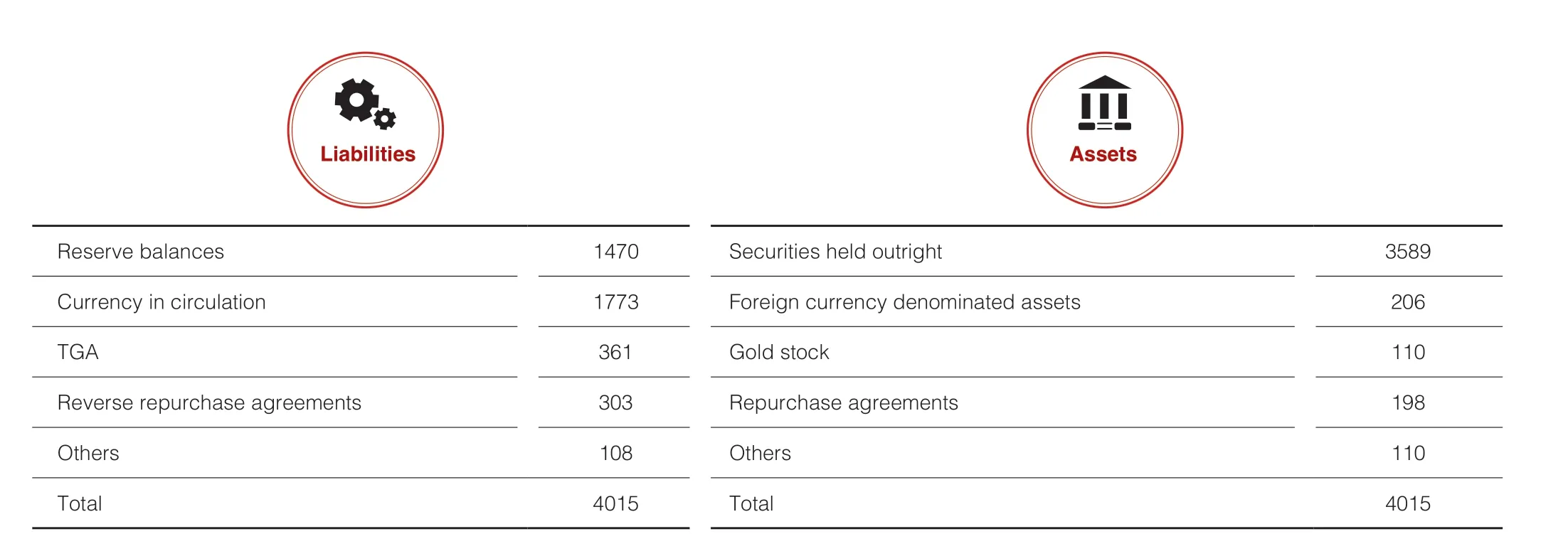

Chart 6 the Structure of the Fed liabilities

Unwinding the Fed’s Balance Sheet

Fourthly, after a period of unwinding the balance sheet, the Fed has reduced the size of reserves in the banking system. At its peak in 2014,reserves exceeded US$2.5 trillion,but for the week through September 4 of 2019, bank reserves deposited at the Fed totaled US$1.49 trillion,data from the central bank show. (See Chart 6)

The combination of the above factors looks very convincing.But there are problems with this explanation. Reserves, for example,have fallen sharply since the Fed scaled back its balance sheet, but they remain far above supercritical levels.

The Federal Reserve conducted a Senior Financial Officer Survey(SFOS) in September 2018 and again in February 2019. The respondents to the September 2018 survey held two-thirds of all reserves and about 60% of their assets in the banking system. According to an estimate by Fed economists, the survey suggested that the minimum level of acceptable reserves in the banking system was between US$650 billion and US$900 billion.

“The desk’s current assessment is that reserves remain ample overall,”said Lorie K. Logan, a senior vice president in the Markets Group of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.“Transacted rates in the federal funds market are relatively stable, and the vast majority of trades are within the target range. Additional monitoring of bank microdata also suggests that reserves are well supplied,” she said in remarks before the Money Marketeers of New York University on April 17, 2019.

The US$1.49 trillion in the week through September 4 of 2019 was well above the line. Moreover, if there is US$12.9 trillion in bank deposits,the US has a reserve ratio of more than 11%, not far behind China.

Of course, the results of a sampling survey may not be accurate,so it requires market trial and error. It cannot be ruled out that the minimum acceptable level of reserves has been reached ahead of schedule. Especially with the current market structure, capital is too concentrated in the hands of a few large institutions, indicating a market polarization.

Chart 7: Structure of the Fed balance sheet(Oct. 16 2019, in billion dollars)

In fact, before this latest round of surging interest rates, there had been abnormal movements in the capital market. The interest rate was frequently close to the upper limit of the policy interest rate range,which forced the Federal Reserve to widen the gap between the interest rate on excess reserves and the policy interest rate upper limit in June and December of 2019, as well as May 2018. Moreover, the twoyear Treasury note yield rose from 1.43% on September 4 to 1.8% on September 13, and the 10-year debt yield rose from 1.46% to 1.9% in the previous two weeks, perhaps indicating that the market was already nervous.

Fixing the Problem

After a series of liquidity injections, interest rates stabilized.However, this is only temporary relief from the symptoms. It does not solve the underlying problem. More fundamental responses include reexpanding balance sheets. (See Chart 7) This would not rule out a new mechanism to allow balance-sheets to be operated along with capital market changes. A new liquidity facility,similar to the Standing Liquidity Facility (SLF) created by the Peoples Bank of China in 2013, could be launched. Powell hinted at such a move when he widened the spread between the federal funds target rate ceiling and excess reserve interest rates in 2018. The money shortage,without doubt, greatly increases the need to create new liquidity management tools.

The former strategy appears to be in the Fed's sights. The central bank has already announced that from October through the second quarter of 2020 it would buy US$60 billion of short-term treasury bills a month.

As a by-product of the cash crunch, the voices of deregulation are becoming louder. Such changes as the Volcker rule and the margin cut will make sense in this climate.

Some people worry that the funding crunch might highlight potential financial risks. For example,corporate debt is growing very fast and concentrated in a few of the riskiest companies, while valuations of stocks, real estate and corporate debt are all at historically high levels.If the economy falters, risks could emerge. Credit spreads would widen and lending standards would rise.

It is true to some extent, though not directly related to the funding crunch, which will be mitigated once the Fed enlarges the size of reserves sufficiently. But for some time now,there has been talk of a possible recession in the US amid rising financial risks. The International Monetary Fund says leveraged loans are reminiscent of the financial crisis of 2008. Former Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen has warned that concerns should be focused on falling standards for leveraged loans and rapidly ballooning corporate debt,rather than just deregulation. The Bank for International Settlement warns that leveraged loans make the financial system more vulnerable. Fed Chairman Powell, testifying before congress in late February 2019, said leveraged lending could lead to macro risks that could be magnified in a downturn. Jay Clayton, chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, recently argued that the high concentration of leveraged loans and the long liquidation cycle, while not necessarily a systemic risk, could create liquidity problems.

So how risky is America’s financial sector? Data from the Federal Reserve show that at the end of 2018,the US private sector debt balance was US$30.9 trillion, or 148% of GDP, of which US$15.2 trillion was in the business sector and US$15.6 trillion in the household sector.Since the financial crisis of 2008, the household sector’s leverage ratio has continued to decline. Its ratios of debt to GDP decreased from 97% to 74%.The commercial sector’s leverage ratio, after deleveraging initially,has climbed to pre-crisis highs.Therefore, the analysis of the US debt risk focuses on the commercial sector.The largest part of the commercial sector is the corporate sector, which has US$9.8 trillion in debt, or 64% of the commercial sector debt.

Non-financial corporate debt and leverage have both exceeded normal levels. Corporate debt has grown at an average rate significantly faster than nominal GDP over the past two decades. The ratio of non-financial corporate debt to GDP is 47%, the highest since 1951. Companies have a high “debt-to-earnings” ratio and the ratio of debt to EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization) is 3.04, much larger than the 2.3 ratio before the 2008 financial crisis.

The high growth in corporate debt in the US over the past two years has been driven largely by loans rather than bond financing. Leveraged loans are particularly notable. Net financing of leveraged loans is at pre-crisis levels. The threshold for leveraged loans is also significantly lower.Firstly, highly leveraged financing is increasing. Highly leveraged finance refers to loans to highly indebted borrowers who have total debt of more than six times EBITDA.Secondly, loans to companies with poor credit histories have soared.Thirdly, more than 60% of new leveraged loans have weak investor protections, compared with less than 30% before the financial crisis.

Borrowers of leveraged loans are mainly companies in the technology,energy, telecommunications and health sectors. The borrowed funds are mainly used for non-productive purposes such as debt repayment,mergers and acquisitions, dividends and share buybacks. Leveraged loans are mostly held by non-bank investors, including those in mutual funds, collateralized loan obligations and a few in banks and insurance companies, among others.

In the bond market, the overall quality of corporate bonds is declining. By the first quarter of 2019,more than 50% of investment- grade rating of BBB or its equivalent, close to the worst on record, involving US$1.9 trillion of bonds.

For all non-financial listed companies, the ratio of debt to total assets averaged 33%, close to a 20-year high. Among them, high-risk listed companies are 40%. It is worth noting that the companies with the fastest increase in debt have obvious risk characteristics: higher leverage,higher interest payments, and lower cash reserves.

In addition to the business sector, there is the household and government sectors. While the household sector is much less leveraged, the US$1.6 trillion in student loans and US$1.1 trillion in credit card loans are structurally significant. As of the end of 2018,the total amount of student loans in default was US$166 billion, with the default rate exceeding 10%. The actual default rate could be twice that, according to an analysis by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.Defaults on credit cards are on the rise, accounting for 83% of losses on consumer loans. The outstanding US government debt exceeds US$22 trillion, accounting for nearly 80% of GDP. The government is projected to run a US$1 trillion deficit in fiscal 2019.

Given that the economy continues to expand, financing is easy in a low interest rate environment. Liquidity is ample, corporate default rates are low, debt risks are manageable, the capital cushion and liquidity coverage of financial institutions are high and the leverage ratio is low. So, the financial system is very sound and there is no systemic risk. However,because the fastest growing debt is concentrated in a few of the riskiest companies and valuations of stocks,real estate and corporate debt are at historically high levels, financial vulnerabilities are easily exposed if the economy falters, credit spreads widen and lending standards rise.

- China Forex的其它文章

- A Look at Offshore Bond Offerings by Chinese Enterprises

- The Division of Labor Amid Economic Globalization

- Sino-US Trade Friction– Can China Cope with Industrial Transfers

- A Review of the Renminbi in 2019

- Roundtable Discussion on China’s Economy

- Global Economic Outlook: Mild Recession orWeak Recovery?