Conventional therapy for moderate to severe inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic literature review

Adérson Omar Mourão Cintra Damião, Matheus Freitas Cardoso de Azevedo, Alexandre de Sousa Carlos,Marcela Yumi Wada, Taciana Valéria Marcolino Silva, Flávio de Castro Feitosa

Abstract BACKGROUND Despite the advent of biological drugs, conventional therapy continues to be used in moderate to severe inflammatory bowel disease (MS-IBD). This study hypothesized that as a standard of treatment and the primary alternative to biologics, conventional therapy should present robust effectiveness results in IBD outcomes.AIM To investigate the effectiveness of conventional therapy for MS-IBD.METHODS A systematic review with no time limit was conducted in July 2017 through the Cochrane Collaboration, MEDLINE, and LILACS databases. The inclusion criteria encompassed meta-analyses, systematic reviews, randomized clinical trials, observational and case-control studies concerning conventional therapy in adult patients with MS-IBD, including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis(UC). Corticosteroids (prednisone, hydrocortisone, budesonide, prednisolone,dexamethasone), 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) derivatives (mesalazine and sulfasalazine) and immunosuppressants [azathioprine (AZA), methotrexate(MTX), mycophenolate, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP)] were considered conventional therapy. The exclusion criteria were sample size below 50; narrative reviews; specific subpopulations (e.g., pregnant women,comorbidities); studies on postoperative IBD; and languages other than English,Spanish, French or Portuguese. The primary outcome measures were clinical remission (induction or maintenance), clinical response and mucosal healing. As secondary outcomes, fecal calprotectin, hospitalization, death, and surgeries were analyzed. The quality of the evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation criteria.RESULTS The search strategy identified 1995 citations, of which 27 were considered eligible(7 meta-analyses, 20 individual studies). For induction of clinical remission, four meta-analyses were selected (AZA and 6-MP showed no advantage over placebo,MTX or 5-ASA in CD; MTX showed no statistically significant difference versus placebo, 6-MP, or 5-ASA in UC; tacrolimus was superior to placebo for UC in two meta-analyses). Only one meta-analysis evaluated clinical remission maintenance, showing no statistically significant difference between MTX and placebo, 5-ASA, or 6-MP in UC. AZA and 6-MP had no advantage over placebo in induction of clinical response in CD. Three meta-analyses showed the superiority of tacrolimus vs placebo for induction of clinical response in UC. The clinical response rates for cyclosporine were 41.7% in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 55.4% in non-RCTs for UC. For induction of mucosal healing,one meta-analysis showed a favorable rate with tacrolimus versus placebo for UC. For secondary outcomes, no meta-analyses specifically evaluated fecal calprotectin, hospitalization or death. Two meta-analyses were retrieved evaluating colectomy rates for tacrolimus and cyclosporine in UC. Most of the twenty individual studies retrieved contained a low or very low quality of evidence.CONCLUSION High-quality evidence assessing conventional therapy in MS-IBD treatment is scarce, especially for remission maintenance, mucosal healing and fecal calprotectin.

Key words: Inflammatory bowel diseases; Steroids; Sulfasalazine; Mesalamine;Azathioprine; Methotrexate; Mycophenolic acid; Cyclosporine; Tacrolimus; 6-Mercaptopurine

INTRODUCTION

Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are the two main disease categories of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a group of idiopathic chronic inflammatory conditions affecting the digestive system[1]. Patients with IBD frequently present a lifelong relapsing and remitting course that has a negative impact on health and quality of life, often resulting in long-term sequelae[2]. Most cases, particularly in CD,are moderate to severe at diagnosis, with a tendency for disease activity to fluctuate over time[3]. CD can progress from pure inflammatory lesions to destructive complications such as intestinal perforation, strictures, abscesses and fistula formation, which may result in irreversible bowel damage leading to loss of gastrointestinal tract function and disability that may require hospitalizations and surgical treatment[4,5].

Symptoms of active UC or relapse include bloody diarrhea with or without mucus,abdominal pain and fecal urgency. This disease presents a cyclical course, including phases of exacerbation and remission, with a variable degree of intensity. Patients with extensive or severe inflammation may experience acute complications, such as toxic megacolon and severe bleeding[6,7]. It is expected that up to 19% of patients with UC have severe disease at the time of diagnosis[8]. In Brazil, a country located in a low prevalence area of IBD, 27% and 32% of UC patients presented severe and moderate disease, respectively[9]. The main goal of treatment for IBD is to achieve and maintain disease remission, prevent complications, hospitalization and surgery, and improve health-related quality of life[1,10]. According to Lichtensteinet al[11], for moderate to severe CD, daily prednisone is indicated until resolution of symptoms and resumption of weight gain. Azathioprine (AZA) and 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) are recommended for the maintenance of steroid-induced remission, and parenteral methotrexate (MTX) is indicated for steroid-dependent and steroid-refractory disease.Patients who are refractory to these agents can be treated with biological therapy,such as infliximab (IFX), adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, ustekinumab and vedolizumab[11]. The conventional therapy for inpatients with severe active UC includes intravenous steroids and monotherapy with intravenous cyclosporin. For patients with steroid-dependent disease or those who are refractory to steroids or immunomodulators, a biological therapy should be considered[2]. In addition to clinical remission, endoscopic remission, expressed as mucosal healing, has become an important endpoint in IBD[12]. This outcome has been correlated with a reduction in surgeries and hospitalizations[13]. Another endpoint recommended by current IBD guidelines is the level of fecal calprotectin, a noninvasive biomarker that has been used to evaluate disease activity in IBD[1,2,13]. The level of this biomarker can be correlated with macroscopic and histological inflammation, as detected by colonoscopy and biopsies[14-17].

Despite the emergence of biological therapy, conventional therapy continues to be prescribed in moderate to severe IBD (MS-IBD), particularly in countries where biologics are not covered by insurance[18,19]. As a standard of treatment and the primary alternative to biologics, conventional therapy should present robust effectiveness results in IBD outcomes. This systematic review aims to investigate data on the efficacy of conventional therapy for MS-IBD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy

A systematic literature review was conducted until July 2017 through MEDLINE databases (viaPubMed), Latin American and Caribbean Literature on Health Sciences(LILACS), and The Cochrane Library. The following strategy was applied to the PubMed database and adapted for other databases, according to the specialties of each one: [“Inflammatory Bowel Diseases” (Mesh) AND (“moderate” OR “severe”)]AND [“Steroids” (Mesh) OR “Prednisone” (Mesh) OR “Prednisolone” (Mesh) OR“Hydrocortisone” (Mesh) OR “Budesonide” (Mesh) OR “Dexamethasone” (Mesh) OR“Sulfasalazine” (Mesh) OR “Mesalamine” (Mesh) OR “Azathioprine” (Mesh) OR“Methotrexate” (Mesh) OR “Mycophenolic Acid” (Mesh) OR “Cyclosporine” (Mesh)OR “Tacrolimus” (Mesh) OR “6-Mercaptopurine” (Mesh)]. The systematic review was executed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement[20,21].

Eligibility criteria

Studies were considered eligible if they met the following criteria: (1) Meta-analysis,systematic reviews, randomized clinical trials (RCTs), observational or case-control studies; (2) studied conventional therapy in adult patients with MS-IBD, including CD or UC; and (3) comparative or single arm studies. Conventional therapy included corticosteroids (prednisone, hydrocortisone, budesonide, prednisolone,dexamethasone), 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) derivatives (mesalazine and sulfasalazine) and immunosuppressants (AZA, MTX, mycophenolate, cyclosporine,tacrolimus, 6-MP). Studies evaluating the maintenance of remission in quiescent disease were considered eligible only if they presented information about the disease severity prior to the remission period.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: sample size below 50, narrative review, specific subpopulations (e.g., pregnant women, comorbidities), studies on postoperative IBD,and languages other than English, Spanish, French or Portuguese. No time limits were applied. The quality of the evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation criteria for each selected study[22].

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers conducted the search in databases using the predefined strategy and selected the studies. In cases without a consensus, a third reviewer was consulted about the eligibility and was responsible for the final decision. The following information was extracted from each selected study: first author name,journal and year of publication, place where the study was conducted, follow-up period, sample size, disease characteristics, study outcomes, and quality of evidence.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome measures were clinical remission (induction or maintenance),clinical response and mucosal healing. As secondary outcomes, fecal calprotectin,hospitalization, death and surgeries were assessed. All outcomes were classified by whatever definition was used in the individual study. The criterion for considering the outcome as induction or maintenance was based on the description of the individual study. If not specified in the article, induction was used for follow-up of up to 12 wk, and maintenance was applied after this period.

RESULTS

The search strategy identified 1995 citations from three databases. After removal of duplicates and exclusion by titles and abstracts, 112 studies were fully reviewed.Eighty-five studies did not meet eligibility criteria, and 27 were considered eligible (7 meta-analyses, 20 individual studies), as presented in Figure 1.

Meta-analysis for primary outcomes: Qualitative review

Induction of clinical remission in Crohn’s disease:In Chandeet al[23], AZA and 6-MP showed no advantage over placebo [risk ratio (RR): 1.23; 95% confidence interval (CI):0.97-1.55], MTX (RR: 1.13; 95%CI: 0.85-1.49) or 5-ASA (RR: 1.24; 95%CI: 0.80-1.91).

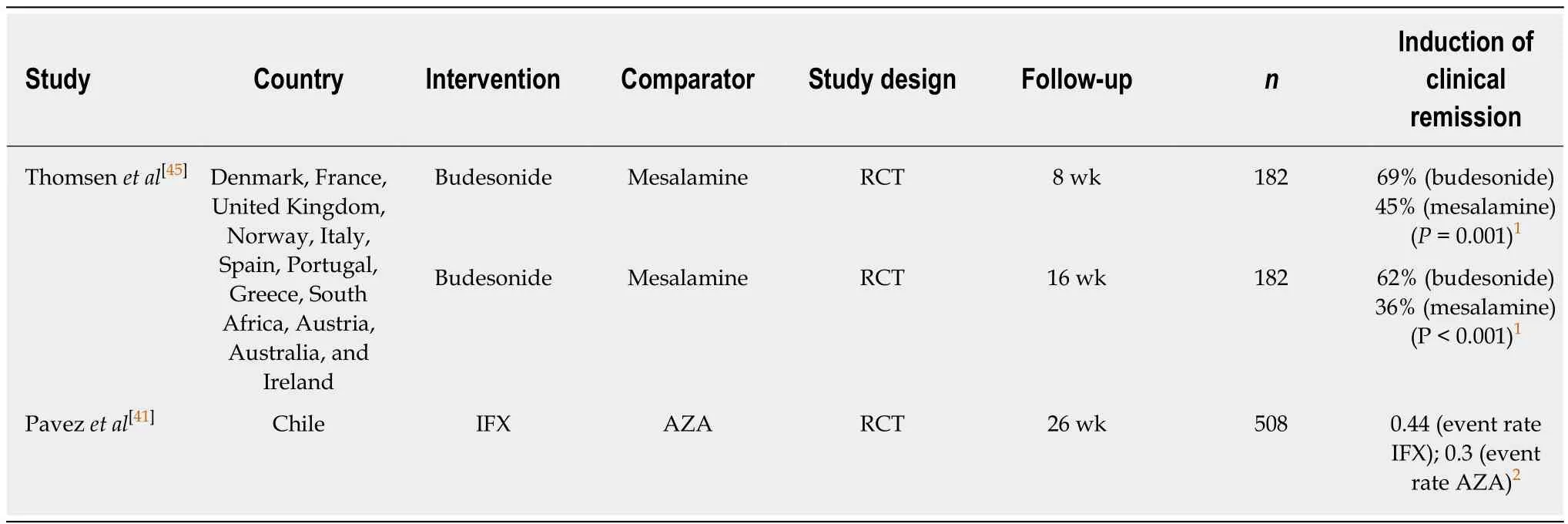

Induction of clinical remission in ulcerative colitis:Chandeet al[24], evaluated MTX versus placebo (RR: 0.96; 95%CI: 0.58-1.59), 6-MP (RR: 0.74; 95%CI: 0.43-1.29), and 5-ASA (RR: 2.33; 95%CI: 0.66-3.64) in UC, with no statistically significant difference.Baumgartet al[25], and Lasaet al[26], indicated numerical superiority of tacrolimus versus placebo for induction of clinical remission in UC [odds ratio (OR): 2.27; 95%CI:0.35-14.75; RR: 0.91; 95%CI: 0.82-1.00, respectively], but the results did not reach statistical significance due to the small number of enrolled patients.

Maintenance of clinical remission in Crohn’s disease:No meta-analysis was found concerning the maintenance of clinical remission in CD.

Maintenance of clinical remission in ulcerative colitis:Only one meta-analysis fulfilled the eligibility criteria for clinical remission maintenance, and that analysis showed no statistically significant difference between MTX and placebo (RR: 0.64;95%CI: 0.28-1.45), 5-ASA (RR: 1.12; 95%CI: 0.06-20.71) or 6-MP (RR: 0.22; 95%CI: 0.03-1.45) in UC[27].

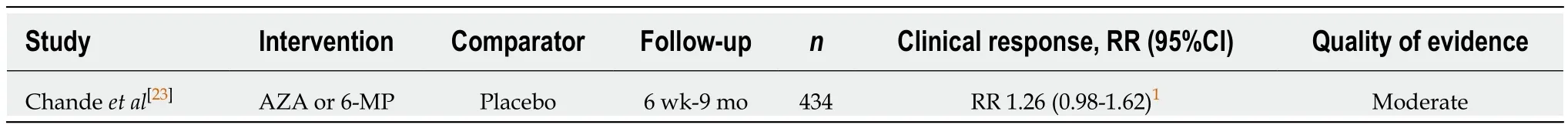

Induction of clinical response in Crohn’s disease:Induction of clinical response was evaluated in CD for AZA and 6-MP; neither demonstrated any advantage over placebo (RR: 1.26; 95%CI: 0.98-1.62)[23].

Induction of clinical response in ulcerative colitis:Komakiet al[28], Baumgartet al[25],and Lasaet al[26]showed the superiority of tacrolimus versus placebo for clinical response in UC (RR: 4.61; 95%CI: 2.09-10.17; OR: 8.66; 95%CI: 1.79-42.00; RR: 0.58;95%CI: 0.45-0.73, respectively). Narulaet al[29], compared IFX versus cyclosporine in patients with UC. The clinical response rates for cyclosporine and IFX were 41.7%vs43.8% in RCTs and 55.4%vs74.8% in non-RCTs (OR: 2.96; 95%CI: 2.12-4.14).

Maintenance of clinical response in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis:No metaanalysis was found concerning the maintenance of clinical response in CD or UC.

Figure 1 Study flow diagram of the article selection procedure. NA: Not applicable.

Mucosal healing:For mucosal healing induction in UC, one meta-analysis showed a favorable mucosal healing rate with tacrolimus versus placebo (RR: 0.59; 95%CI: 0.46-0.74) in a 12-wk horizon analysis[26]. When compared to IFX in CD, AZA was not favorable for induction of mucosal healing during a follow-up period of 26 wk[23]. The results of the retrieved meta-analyses, as well as their assessed quality, are presented according to primary outcome in Tables 1-7.

Meta-analysis for secondary outcomes: Qualitative review

For secondary outcomes, no meta-analysis was found to evaluate fecal calprotectin,hospitalization or death specifically. For colectomy, two meta-analyses for UC were retrieved. As shown in Table 8, the first revealed a 0% colectomy rate in both the tacrolimus and placebo arms[28]. In Narulaet al[29], colectomy rates at 3 mo in RCTs did not achieve a significant difference between cyclosporine and IFX (OR: 1.00; 95%CI:0.64-1.59), with pooled 3-mo colectomy rates of 26.6% for IFX and 26.4% for cyclosporine. Among non-RCTs, the pooled 3-mo colectomy rate was 24.1% for IFX and 42.5% for cyclosporine (pooled OR: 0.53; 95%CI: 0.22-1.28; no significant difference between the two groups). Colectomy rates at 12 mo did not show any significant difference between the two groups in RCTs (OR: 0.76; 95%CI: 0.51-1.14).The 12-mo colectomy rate was significantly lower for IFX in non-RCTs (20.7% for IFXvs36.8% for cyclosporine; pooled OR: 0.42; 95%CI: 0.22-0.83).

Individual studies: Qualitative review

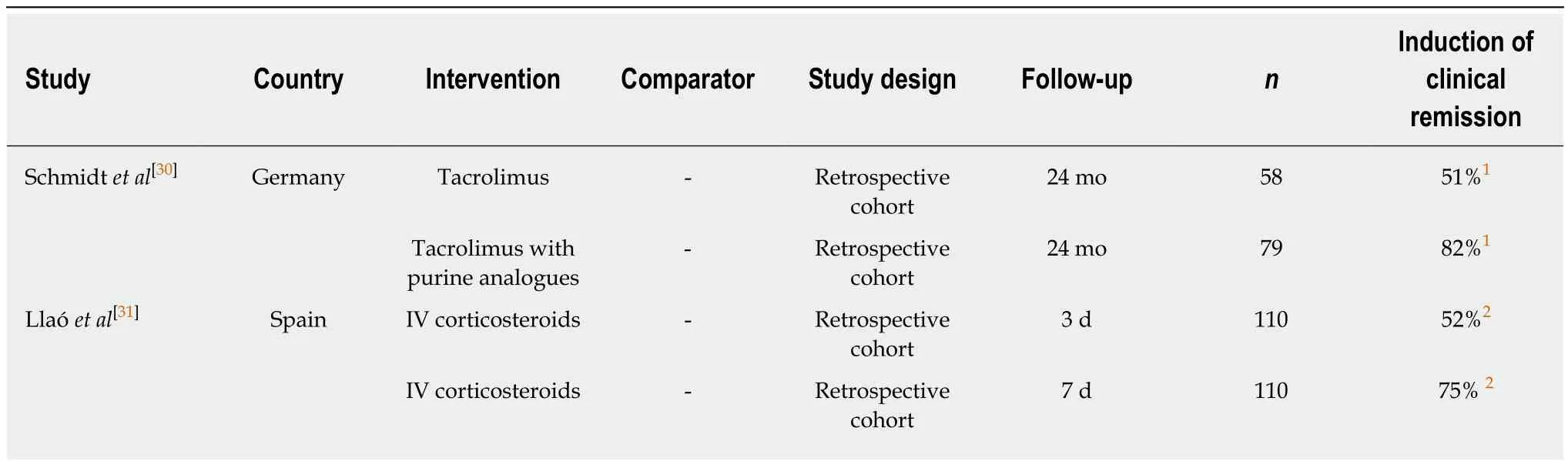

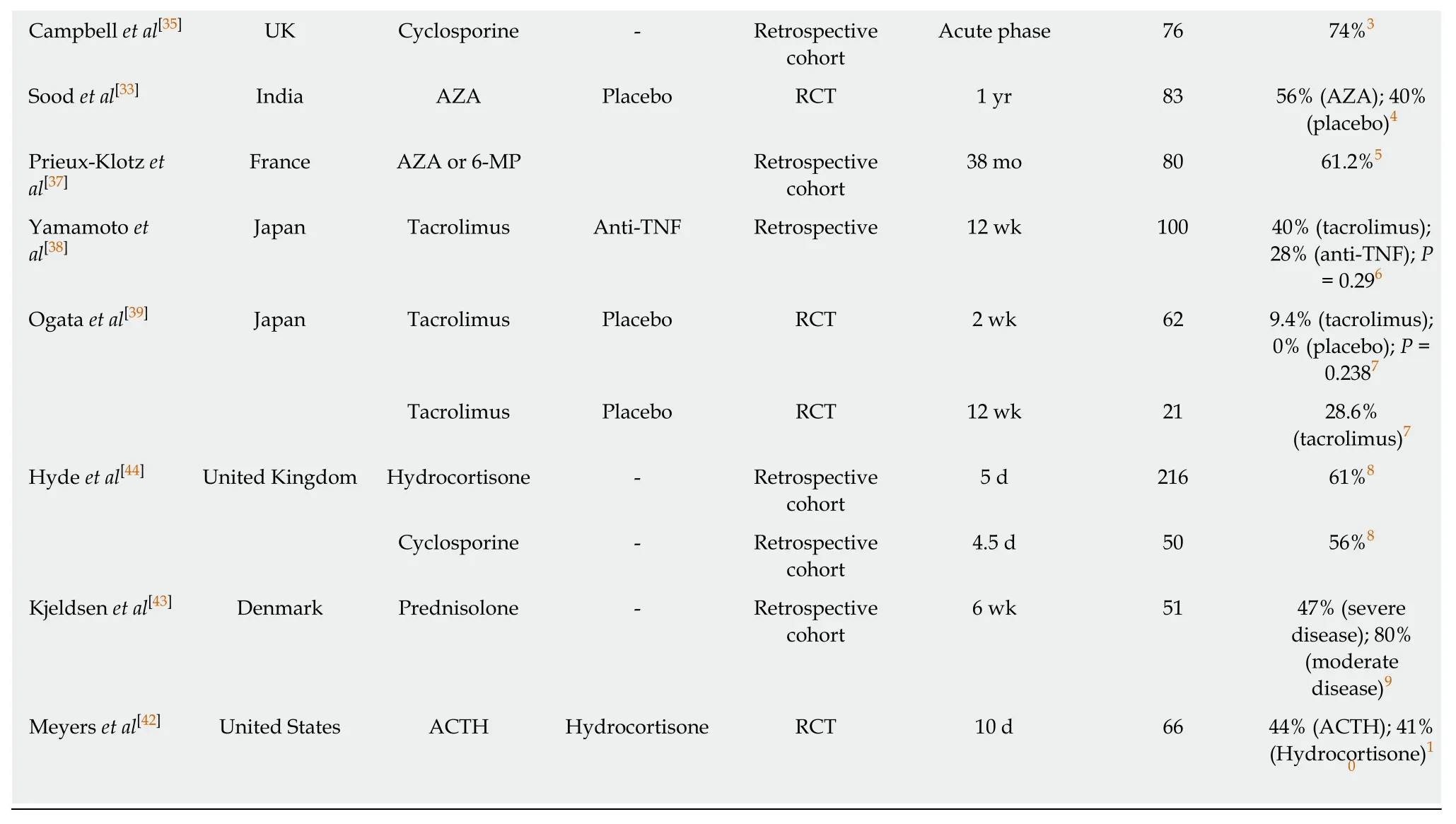

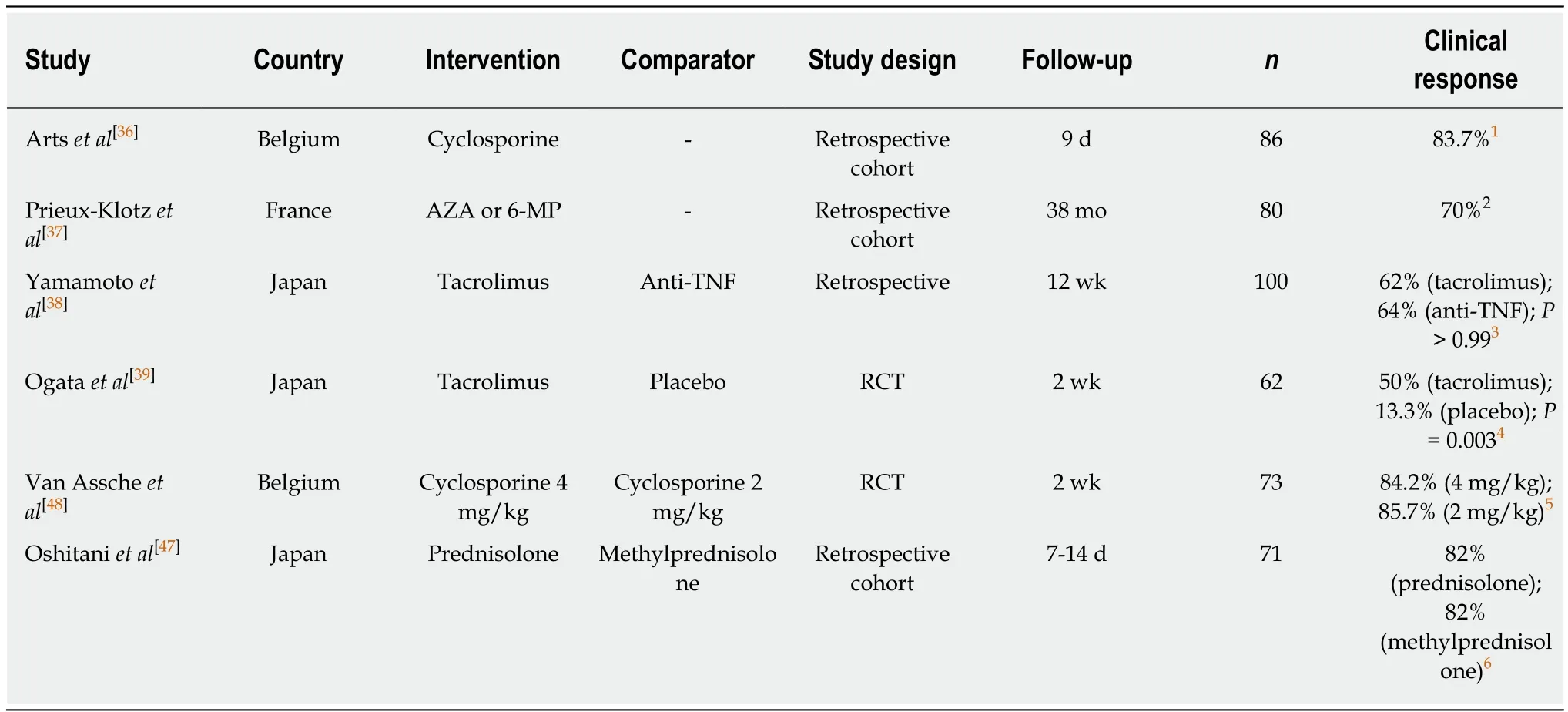

Twenty individual studies were included in this systematic review[30-49]. They were mainly in UC, with small sample sizes and short follow-up. Therapies included cyclosporine, 5-ASA, tacrolimus, corticosteroids, AZA, and 6-MP (Tables 9-14). The primary outcomes were evaluated, but the majority of studies had retrospective cohorts with low or very low levels of evidence. As a secondary outcome, IBD-related surgeries were the only outcome where data were available (Tables 15 and 16).

DISCUSSION

Table 1 Meta-analyses included for induction of clinical remission in Crohn’s disease

This systematic review aimed to study data on the effectiveness of conventional therapy for MS-IBD. Despite being a very broad theme, the objective was to understand the panorama of available evidence about conventional treatment and its qualities, more than to evaluate the individual efficacy of each drug.

The choice of outcomes was based on the currently most relevant outcomes:Clinical remission and response (induction and maintenance), mucosal healing, fecal calprotectin, hospitalization, death and surgeries. Mucosal healing is considered a more objective goal than clinical remission for evaluating inflammatory disease activity in patients with IBD, and it should be measured in both clinical trials and medical practice to evaluate the management of IBD[50]. In clinical trials on IBD, this endpoint has been defined as complete absence of ulcerative lesions or by specific endoscopic scores such as the Simple Endoscopic Score for CD and the CD Endoscopic Index of Severity in CD or Mayo 1 or 0 for UC[51]. Mucosal healing can alter the natural history of IBD by reducing the frequency of hospitalization and the lifetime risk for surgery and colorectal cancer, in addition to being associated with disease remission[15,50]. In addition, there is a current consensus in the regulatory and academic environment that clinical studies in IBD need an imaging endpoint, such as mucosal healing, with or without histopathology[52]. In this systematic review, only two meta-analyses were retrieved that evaluated mucosal healing[23,26]and four individual studies[37-39,47,53], all for patients with UC. This paucity of available studies supports our claim that there is a lack of data assessing the effectiveness of conventional therapy for mucosal healing.

Despite the advantages of using mucosal healing as an outcome measure, it is usually associated with invasive and costly procedures, which can be barriers,especially for developing countries[14]. Thus, fecal calprotectin has been suggested as a surrogate marker for assessing mucosal healing[15]. In general, biomarkers (wide range of substances present in blood, stool, or urine) play important roles in research:reduce placebo response; select subjects with symptoms directed by specific inflammatory processes; predict the clinical relapse likelihood; identify patients with mucosal healing; provide clinical disease activity indexes; follow disease activity[54].Fecal calprotectin is probably an alternative marker for assessing IBD disease activity,especially for UC[16]. In the present study, no eligible studies evaluating fecal calprotectin were found.

Colectomy rates were reported often in studies, mainly for UC, and low rates may reflect clinical improvement, as well as reduction of resource utilizationvsthose who have to undergo colectomy. Death was not an outcome assessed directly as a study objective, perhaps because studies did not have a long enough follow-up period to evaluate this endpoint. Hospitalization was also not explored in the studies we retrieved. Positive results were observed for tacrolimus in the treatment of UC. The drug presents good results for induction and maintenance of remission, mucosal healing and risk reduction of surgical treatment, and in some analyses, it is superior to IFX. On the other hand, tacrolimus is very uncommonly used in clinical practice and very rarely referenced by treatment guidelines. Therefore, we believe that tacrolimus use should be reviewed by IBD consensus.

The main limitations of this study are the wide range of eligible drugs, the considerable number of outcomes and the variety of ways to measure these endpoints. Several instruments are used in individual studies for measuring clinical disease activity in CD (CD Activity Index, Harvey Bradshaw Index, Van Hess or Dutch Index, Therapeutic Goals Score, International Organization of Inflammatory Bowel-Disease-Oxford Index) and for evaluating and measuring endoscopic response to therapy (CD Endoscopic Index of Severity, Rutgeerts Endoscopic Index)[54]. For UC,the usual instruments for measuring clinical disease activity are Truelove and Witts Score, Lichtiger Score, Powell-Tuck Index, Clinical Activity Index, Mayo Score,Sutherland Index, Physician Global Assessment. These instruments generally include measurements of stool frequency, presence of blood, endoscopic findings, abdominal pain and gastrointestinal symptoms, laboratory findings, extraintestinal manifestations, temperature, physician’s global assessment and patient functional evaluation[54]. To circumvent the problem of the variety of instruments for the assessment of illness severity at baseline and response to treatment measurement, we applied the indexes and definitions as used in each individual study.

Table 2 Meta-analyses included for induction of clinical remission in ulcerative colitis

Some studies cited in treatment guidelines and used as a source of evidence were excluded from this review. The reasons varied but were mainly because the studies contained different disease severities or specific subpopulations, such as those in the postoperative period. Furthermore, studies with no disease severity specification were excluded, according to eligibility criteria. Therefore, only studies in which the disease was explicitly moderate to severe were considered. In this way, some major works may have been excluded. It is important to note that some negative results of conventional therapy in moderate to severe disease do not mean that immunosuppressants have no function in IBD. The exclusion of studies with mild disease and those which did not specify the disease severity may have skewed our results against them. An example is the use of AZA and 6-MP in corticosteroiddependent patients, where such medications may be useful especially for remission maintenance. Overall, little high-quality evidence is available on conventional therapy for MS-IBD patients to robustly assess their effectiveness in this patient population,which did not encompass all available medications, for all pathologies and with all relevant outcomes for response and prognosis. This review suggests that conventional therapy for MS-IBD does not have scientific evidence of quality that supports its use as a standard for MS-IBD.

In conclusion, there are few studies evaluating objective outcomes in MS-IBD with conventional therapy, especially for remission maintenance, mucosal healing and fecal calprotectin. Additionally, the quality of existing studies is mainly very low or low. As conventional therapies are usually the main treatment for MS-IBD, robust researches are required to enhance the evidence on their effectiveness because they are currently prescribed to many IBD patients.

Table 3 Meta-analyses included for maintenance of clinical remission in ulcerative colitis

Table 4 Meta-analyses included for induction of clinical response in Crohn’s disease

Table 5 Meta-analyses included for induction of clinical response in ulcerative colitis

Table 6 Meta-analyses included for induction of mucosal healing in Crohn’s disease

Table 7 Meta-analyses included for induction of mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis

Table 8 Meta-analyses included for inflammatory bowel disease-related surgeries in ulcerative colitis

Table 9 Individual studies included for induction of clinical remission in Crohn’s disease

Table 10 Individual studies included for induction of clinical remission in ulcerative colitis

1Clinical remission defined by a Lichtiger score ≤ 3;2Clinical remission defined as mild activity or inactive disease according to the Montreal severity score, with no need for rescue treatment at day 7 after starting intravenous CS;3Response defined as a reduction of bowel frequency to fewer than three daily and a C-reactive protein < 45 mg/L;4Clinical remission defined as clinical improvement with absent of symptoms of active disease (rectal bleeding, bowel frequency) with sigmoidoscopic appearance of grade 0-1 and normal histological pattern;5Clinical remission defined as a partial Mayo Clinic score ≤ 2 without any clinical subscore > 1;6Clinical remission defined as a score of 0 in the clinical section (both stool frequency and rectal bleeding);7Clinical remission was defined as a total DAI score ≤ 2 with an individual subscore of 0 or 1;8Clinical remission defined as bowel frequency less than three stools per day, no visible blood, no fever or pain;9Remission was assessed in accordance with a modified Truelove and Witts index;10Remission defined as patient receiving no therapy or only prophylactic sulfasalazine. 6-MP: 6-mercaptopurine; ACTH: Adrenocorticotrophic hormone;AZA: Azathioprine; CI: Confidence interval; IV: Intravenous; MTX: Methotrexate; n: Number of patients; RCT: Randomized clinical trial; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; DAI: Disease Activity Index.

Table 11 Individual studies included for maintenance of clinical remission in ulcerative colitis

Table 12 Individual studies included for induction or maintenance of clinical response in Crohn’s disease

Table 13 Individual studies included for induction or maintenance of clinical response in ulcerative colitis

Table 14 Individual studies included for mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis

Table 15 Individual studies included for surgeries related to Crohn’s disease

Table 16 Individual studies included for surgeries related to ulcerative colitis

IV: Intravenous; n: Number of patients; N/A: Not available; RCT: Randomized clinical trial; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) frequently present a lifelong relapsing and remitting course with negative impact on health and quality of life, besides long-term sequelae. IBD main treatment goal is the achievement and maintenance of disease remission. Conventional therapies are indicated for patients with moderate to severe disease, despite the advent of biological drugs.Some relevant outcomes, such as clinical remission and endoscopic remission has been correlated with surgeries and hospitalizations reduction.

Research motivation

Conventional therapy continues to be used in moderate to severe IBD (MS-IBD) especially in countries where biologics are not covered by insurance. Thus, extensive knowledge on the efficacy and safety of conventional therapy is necessary.

Research objectives

This systematic review aims to investigate data on the efficacy of conventional therapy for MSIBD.

Research methods

A systematic review was conducted through the Cochrane Collaboration, MEDLINE, and LILACS databases searching for studies concerning conventional therapy in adult patients with MS-IBD, including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). Corticosteroids (prednisone,hydrocortisone, budesonide, prednisolone, dexamethasone), 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA)derivatives (mesalazine and sulfasalazine) and immunosuppressants [azathioprine (AZA),methotrexate (MTX), mycophenolate, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP)] were considered conventional therapy. Primary outcome measures were clinical remission (induction or maintenance), clinical response and mucosal healing.

Research results

For induction of clinical remission, AZA and 6-MP showed no advantage over placebo, MTX or 5-ASA in CD; MTX showed no statistically significant difference versus placebo, 6-MP, or 5-ASA in UC; tacrolimus was superior to placebo for UC in two meta-analyses. One meta-analysis evaluated clinical remission maintenance, showing no statistically significant difference between MTX and placebo, 5-ASA, or 6-MP in UC. AZA and 6-MP had no advantage over placebo in induction of clinical response in CD. Three meta-analyses showed the superiority of tacrolimus versus placebo for induction of clinical response in UC. The clinical response rates for cyclosporine were 41.7% in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 55.4% in non-RCTs for UC.For induction of mucosal healing, one meta-analysis showed a favorable rate with tacrolimus versus placebo for UC. For secondary outcomes, no meta-analyses specifically evaluated fecal calprotectin, hospitalization or death. Two meta-analyses were retrieved evaluating colectomy rates for tacrolimus and cyclosporine in UC. Most of the twenty individual studies retrieved contained a low or very low quality of evidence.

Research conclusions

High-quality evidence assessing conventional therapy in MS-IBD treatment is scarce, especially for remission maintenance, mucosal healing and fecal calprotectin.

Research perspectives

From this systematic review, it could be seen, that further studies with high quality and realworld evidence are needed to prove the effectiveness of conventional therapy in MS-IBD.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank SENSE Company Brazil for conducting the literature search and for providing medical writing support in developing drafts of this manuscript. This support was funded by Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Brazil. The authors were responsible for analysis and interpretation of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published; and commitment to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2019年9期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2019年9期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Liver stem cells: Plasticity of the liver epithelium

- Reaction of antibodies to Campylobacter jejuni and cytolethal distending toxin B with tissues and food antigens

- Integrated network analysis of transcriptomic and protein-protein interaction data in taurine-treated hepatic stellate cells

- Computed tomography scan imaging in diagnosing acute uncomplicated pancreatitis: Usefulness vs cost

- Targeted puncture of left branch of intrahepatic portal vein in transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt to reduce hepatic encephalopathy

- Optimized protocol of multiple post-processing techniques improves diagnostic accuracy of multidetector computed tomography in assessment of small bowel obstruction compared with conventional axial and coronal reformations