Assessing adequacy of emergency provider documentation among interhospital transferred patients with acute aortic dissection

Mark Rose, Carina Newton, Benchaa Boualam, Nancy Bogne, Adam Ketchum, Umang Shah, Jordan Mitchell,Safura Tanveer, Tucker Lurie, Walesia Robinson, Rebecca Duncan, Stephen Thom, Quincy Khoi Tran,

1 Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Maryland, School of Medicine, Baltimore, USA

2 Program of Trauma, The R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center, University of Maryland, School of Medicine, Baltimore,USA

3 University of Maryland at College Park, College Park, USA

4 University of Maryland, School of Medicine, Baltimore, USA

KEY WORDS: Acute aortic dissection; EMTALA; Interhospital transfer; Documentation;Compliance

INTRODUCTION

Acute aortic dissection (AoD) is a hypertensive emergency associated with high mortality and morbidity.[1-4]Type A dissection occurs when the lesion involves the ascending aorta, whereas Type B only involves the descending aorta.[5]Treatment protocols depend upon these classifications, with Type A being a surgical emergency,while Type B may be medically managed with surgical intervention available at the sign of end-organ damage.[5]Other aortic diseases less common than dissection, such as intramural hematoma, ulcers, and aneurysms are also treated as dissections depending on their location.[5]

In the acute phase of aortic dissection, the American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines recommend lowering heart rate to ≤60 beats/minute, systolic blood pressure (SBP) to ≤120 mmHg and aggressive pain control.[1]Consequently, critically ill patients are frequently transferred to higher care centers with cardiac or thoracic or vascular surgery subspecialties for further management, since most hospitals do not have these definitive care capabilities.[6,7]

Among interhospital transferred patients,documentation of clinical care (DoCC) is important as it represents the record of treatment prior to transfer.[8]So,adequate documentation of clinical care (ADoCC) is associated with improved patient outcomes.[9,10]Also,documentation in compliance with the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (DoEMTALA)is crucial.[8]Therefore, established guidelines exist for transferring critically ill patients between hospitals to improve compliance with the legal requirements of EMTALA.[8,11]For interhospital transferred patients,EMTALA requirements stipulate that patients should be accompanied by records of treatment from the referring hospitals; a consent form signed by the patient or family;or documentation as to why such signatures were not required. Additionally, the referring physicians should document acceptance from the accepting physicians.[8]

Previous studies have indicated that documentation of clinical care among interhospital transferred patients is inadequate.[12,13]However, the quality of documentation of clinical care for interhospital transferred patients with acute aortic dissections among emergency providers(EP) is unknown. This study investigated how well EPs documented their clinical care and their compliance with existing interhospital transfer guidelines according to EMTALA statutes.

METHODS

Design and setting

This retrospective study examined data on adult patients admitted to a single quaternary academic medical center. The study period was between January 1,2011 and September 30, 2015. The Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Patient selection

Adult patients for potential inclusion were identified within our electronic medical record system using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th version(ICD-9) and coding for aortic diseases at 441.XX.[14]Patients who were transferred directly from another emergency department (ED) to our academic medical center for management of acute aortic dissections were included. Patients who initially presented to our academic medical center and those who were not a direct transfer from a referring ED were excluded.Also, patients with referring ED records missing were excluded.

Data collection and management

Data was extracted from referring ED records following the process of high quality chart review standards.[15]Junior investigators (MR, US, AK, BB,NB, CN, JM, ST), who were not blinded to the study hypothesis, were first trained by the principal investigator(QKT) regarding data extraction. Data was extracted to a standardized Microsoft Access form (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) and 10% was randomly reviewed by a junior investigator (BB) to maintain an interrater’s agreement of at least 90% for documentation of clinical care and EMTALA compliance. The team met every three months to discuss data extraction issues and to adjudicate disagreements until data collection was completed.

Independent variables

Demographic variables such as age, gender, ED triage date and time, ED departure date and time, type of transport, and hospital teaching status were extracted from the referring ED records. Clinical variables such as Emergency Severity Index (ESI), types of aortic dissection (Type A or Type B), other categories of aortic diseases (intramural hematoma, ulcers, and aneurysm),requirement of invasive mechanical ventilation, and use of continuous infusion of medication were also collected.Vital signs, such as blood pressures and heart rates, at both ED triage and ED departure were also extracted.

Outcome measures

The research team a priori defined the primary and secondary outcomes according to existing guidelines.The primary outcome was the percentage of ED records indicating adequate documentation of clinical care(ADoCC). Documentation of clinical care was adequate if both of the following were present: (1) presence of recorded blood pressure and heart rate at ED triage and(2) presence of two or more (≥2) assessments of blood pressure and heart rate, in addition to triage vital signs,before and after diagnosis of acute aortic dissection.T his definition for adequate clinical care was decided a priori during the planning phase based on previous studies and the assumption that more monitoring would lead to more intervention.[10]Patients with hypertensive emergencies such as AoD need close monitoring.[16]Furthermore, frequent blood pressure monitoring in patients with AoD was associated with better odds of blood pressure control.[17]Documentation of clinical care was inadequate if either or both components were missing. The secondary outcome was percentage of ED records indicating adequate documentation of EMTALA compliance (ADoEMTALA), which was defined a priori according to existing guidelines for interhospital transfer of critically ill patients.[8,11]Referring ED records were adequate for EMTALA compliance if both of the following were present: (1) presence of documentation of consultation with accepting physicians and (2) presence of transfer consent signed by the patient or family. Blank consent forms, without ED providers’ documentation of discussion about transfer with patients or patient families,were considered inadequate. Similarly, inadequate documentation of EMTALA compliance resulted from missing either or both components of EMTALA documentation.

Also, the study assessed the association of demographic or clinical variables with inadequate documentations, as well as whether inadequate documentations were associated with patients’ SBP and HR meeting AHA guidelines (SBP ≤120 mmHg and HR≤60 beats/minute) at ED departure.

Data analysis

Variables were shown as means with standard deviation (SD), medians with interquartile ranges [IQR],and percentages where appropriate. Categorical data was compared using the Chi-square test. Outcomes were dichotomized as inadequate or adequate documentations.Then, association between patients’ demographic variables, clinical variables, and outcomes were assessed using simple and multiple logistic regressions.Association of individual variable was first assessed using simple logistic regressions. Since a conservative P-value of <0.05 may fail to identify significant factors in multiple logistic regression,[18,19]we chose factors with P-value ≤0.10 from simple logistic regressions to be included in multiple logistic regressions. For intentionto-treat analysis of association between inadequate documentations and referring ED departure SBP, HR meeting AHA guidelines, any missing SBP or HR data at ED departure was imputed with the mean value from the population’s mean values. All P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC)and Sigma Plot version 14 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA).

RESULTS

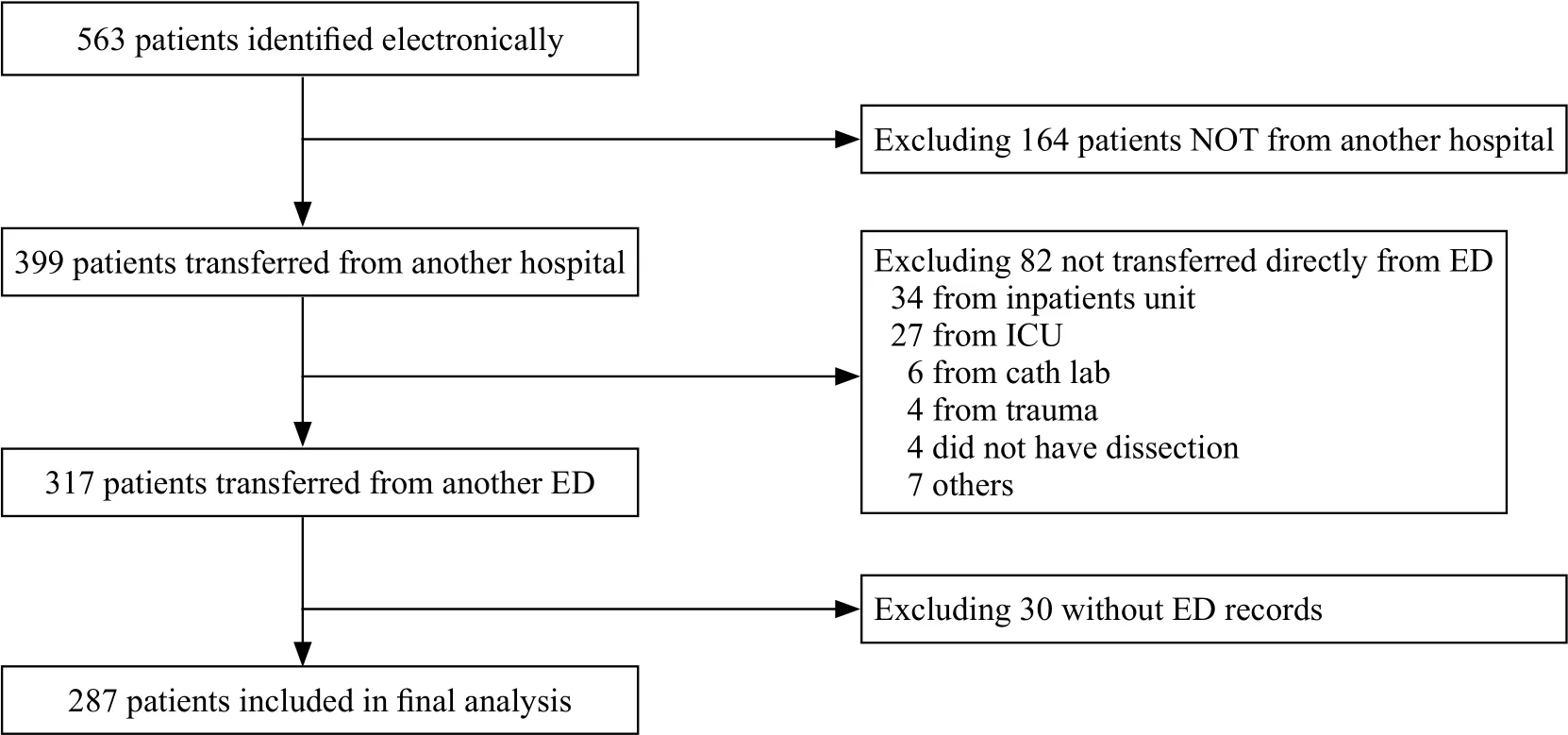

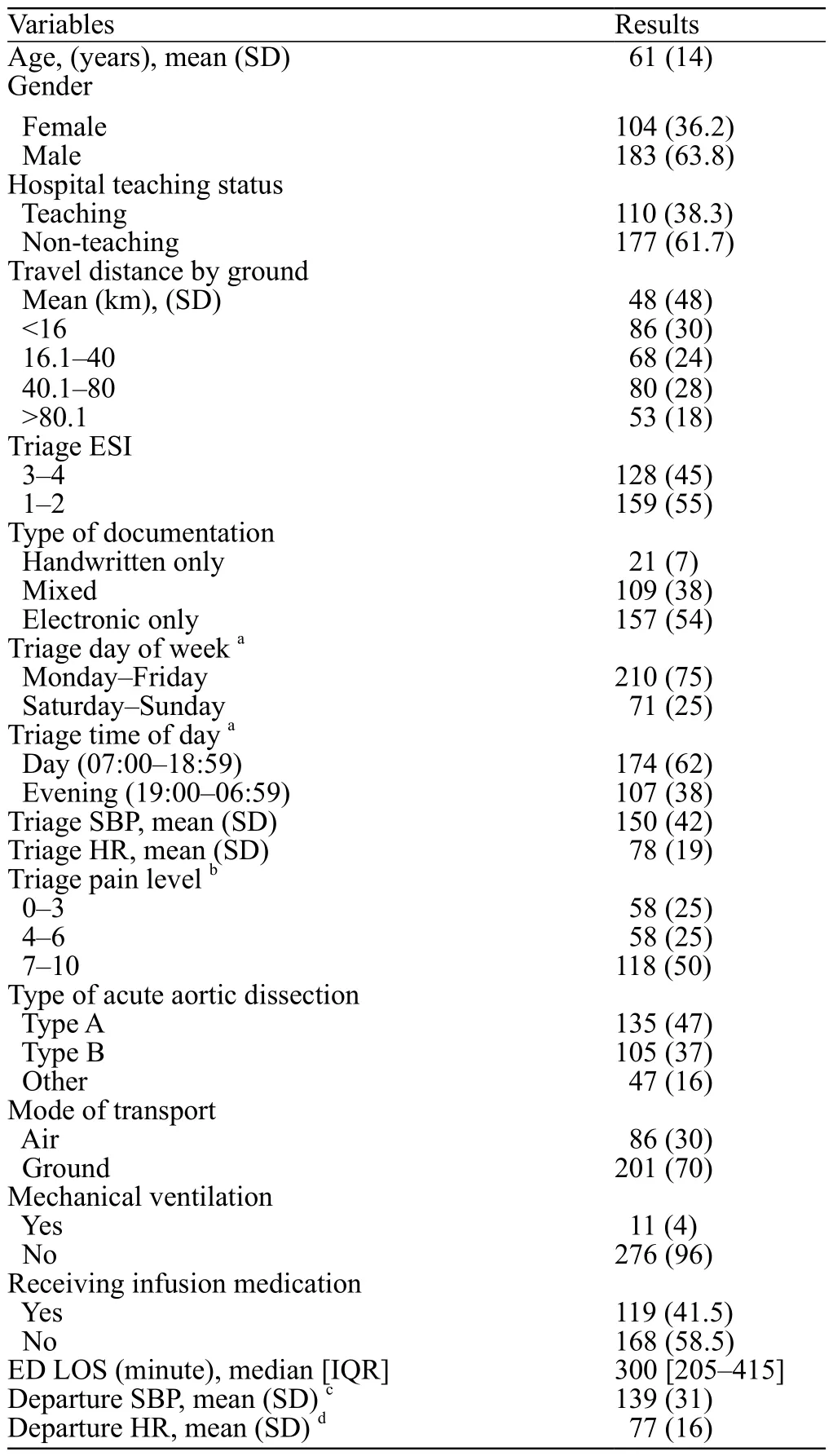

There were 563 patients electronically identified with 287 patients included in the final analysis (Figure 1).Demographic characteristics of the patients are displayed in Table 1. Mean patient age was 61 (14) years; median length of stay in the ED was 300 [205-415] minutes;mean triage SBP and HR were 150 (42) mmHg and 78(19) beats/minute, respectively; mean SBP and HR at referring ED departure were 139 (31) mmHg and 77 (16)beats/minute, respectively.

Figure 1. Patient selection diagram.

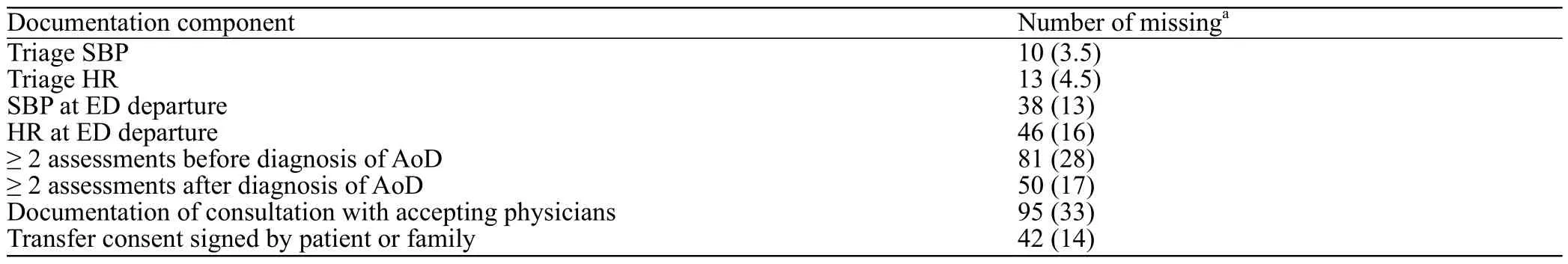

Among 287 ED clinical records analyzed, 105(36.6%) contained adequate documentation of clinical care. However, 182 (63.4%) ED clinical records were inadequate regarding documentation of clinical care. In these cases, the records were absent for appropriate vital sign assessments at ED triage or did not contain ≥ 2 vital sign assessments before and after diagnosis of aortic dissection or were missing both components. Also, 166(57.8%) ED records met the established guidelines for EMTALA regarding interhospital transferred records,while 121 (42.2%) ED records were inadequate. In the latter, the records did not contain documentation of consultation with accepting physicians or a signedtransfer consent or were missing both components.Overall, only 67 (23%) ED records were adequate for both documentation of clinical care and compliance with the EMTALA statutes. The missing components are listed in (Table 2).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of adult patients transferred directly from a referring emergency department (ED) to a quaternary academic center for further management of acute aortic dissections, n (%)

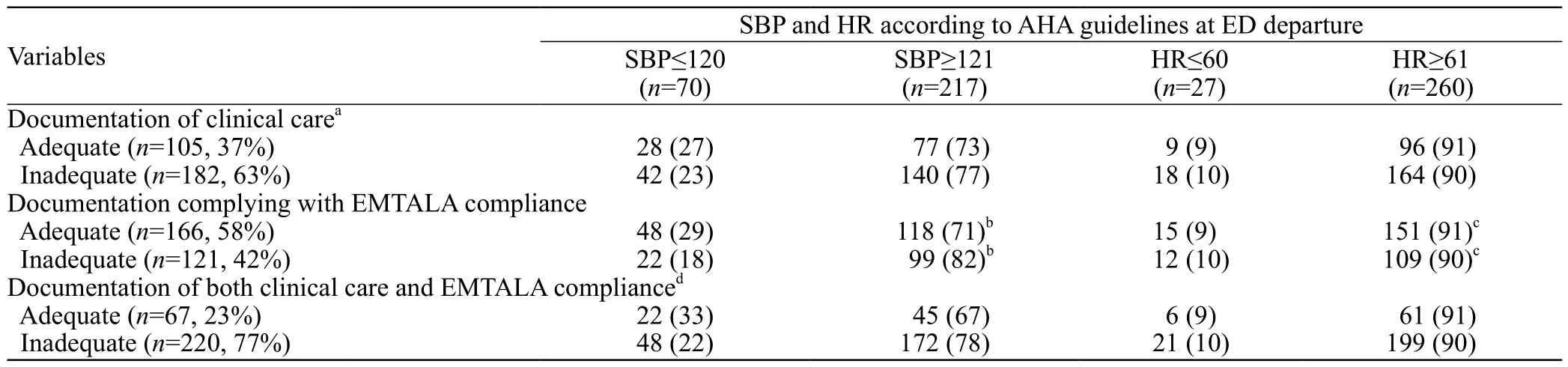

The study also showed that documentation of clinical care was not associated with significant differences in the percentage of patients meeting the AHA guideline for systolic blood pressure (SBP ≤120 mmHg) and heart rate (≤60 beats/minute) at ED departure (Table 3). While inadequate documentation of EMTALA compliance was not associated with percentages of patients meeting AHA guideline for heart rate at ED departure, IDoEMTALA was associated with significant increased odds (OR 1.8,95% CI 1.03-3.2, P-value 0.04) of patients not meeting AHA guidelines for SBP at ED departure.

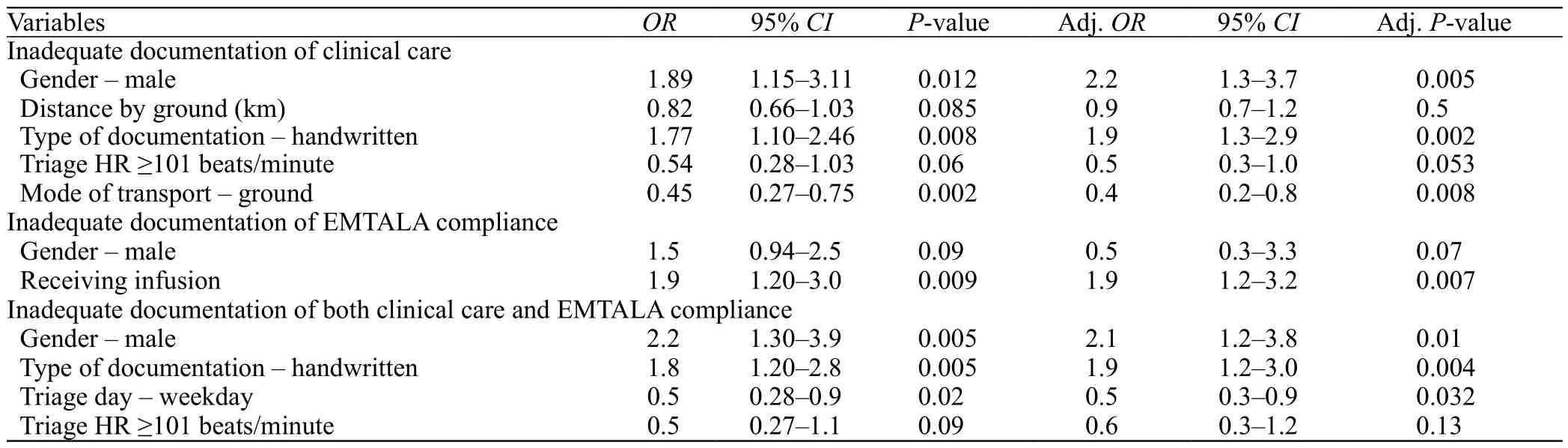

Factors associated with inadequate documentation of clinical care (IDoCC) (Table 4) were male gender(OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.3-3.7) and handwritten type of documentation (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.3-2.9). Transport by ground was associated with a lower risk of IDoCC(OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.2-0.8). Receiving infusion in the ED was the only factor associated with increased risk of IDoEMTALA (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.2-3.2). On the other hand, presenting to the ED during the weekday was associated with a lower risk of IDoEMTALA (OR 0.5,95% CI 0.3-0.9). Factors associated with IDoCC and IDoEMTALA compliance in multiple logistic regressions included male gender (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.2-3.8) and handwritten type of documentation (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.2-3.0). Other variables were not significantly associated with inadequate documentation.

DISCUSSION

The study showed that overall documentation of interhospital transferred patients with acute aortic dissection from emergency departments was inadequate.Up to 63% of ED documentations of clinical care were inadequate while 42% did not comply with EMTALA statutes. Moreover, the study showed that patients whose records complied with the EMTALA statutes were associated with a higher likelihood of having systolic blood pressure ≤ 120 mmHg at ED departure,as recommended by the American Heart Association guidelines.

Caring for critically ill patients in crowded EDs while maintaining good documentation of clinical care prior to transferring is challenging. Prior studies indicate that documentation regarding interhospital transferred patients has been poor.[12,13]In one case, 33% of ED records missed documentation of consultation for patients who were transferred from referring EDs to a tertiary care center.[12]Furthermore, poor documentation of clinical care from referring providers resulted in more adverse events and more testing at the accepting facilities, while complete transfer documentation was associated with lower in-hospital mortality at the accepting hospitals.[13]Our study data showed that adequate documentation of EMTALA compliance was significantly associated with AoD patients having SBP meeting the AHA guidelines. This finding is consistent with previous studies, which illustrate that adequate documentation in compliance with existing guidelines improves patient outcomes. For example, Nevrekar et al[9]showed that adequate documentation of care according to AHA guidelines during cardiac arrest in the ED is associated with an increased rate of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC).

Besides potentially improving patient outcomes,adequate documentation is also significant to avoid litigation. The ED record is the lasting record of patient-physician interaction, and as such, any documentation will be potential risk for litigation, especially when there is an adverse outcome.[20]Emergency providers involved in the care of AoD patients are at high risk for litigation due to high mortality and morbidity of the disease.[21]However, thorough documentation has been shown to avoid litigation among other high risk practices.[22]Furthermore, non-compliance with EMTALA statutes while common at the hospital level and rare at the ED-level visit,[23]could result in a civil monetary penalty (up to $50,000) against individual emergency physicians as these fines are not covered by malpractice insurance.[24]Therefore, physicians should diligently document their clinical care and ensure compliance with EMTALA when transferring patients to other hospitals.

Table 2. List of missing documentation components, n (%)

Table 3. Outcome results of Emergency Providers’ documentation of clinical practice and compliance with EMTALA requirement. Patient’s hemodynamic parameters at departure from referring EDs were compared between adequate or inadequate documentations. AHA guideline recommendations for AoD treatment in the acute phase: systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≤120 mmHg and HR ≤60 beats per minute (beats/minute),n (%)

Table 4. Multiple logistic regressions assessing association between different demographic and clinical variables and inadequate documentation.Variables with P-value ≤ 0.10 from simple logistic regressions were included in multiple logistic regressions

To date, there is no standard for assessing the quality of documentation for interhospital transferred patients.[12]Each investigator uses different definitions for their studies involving transferred patient documentation. For example,in Harl et al,[12]the investigators considered inclusion of laboratory values and any digital imaging studies on compact discs as adequate documentation among patients who were transferred for surgical interventions from EDs. Yet, Usher et al,[13]which involved the transfer of admitted patients, considered presence of progress notes,reconciliation of medications, and discharge summaries as important components. This study involved a group of AoD patients who required rapid reduction of heart rate and blood pressure; thus, frequent blood pressure and heart rate assessments were considered important components. Future studies should focus on which part of the written record impacts a patient’s satisfaction or other patient-centered outcomes.

This study had several limitations. First, emergency providers might not have documented all performed patient assessments. Second, the study excluded patients who were not accompanied by any records from a referring ED. While not providing the accepting facilities with any ED records would violate existing interhospital transfer guidelines,[8,11]by excluding these patients, the study underestimated the percentage of patients with poor documentation. Third, this study did not consider pain management documentation as a criterion in the study, although pain management is a component of the AHA guidelines for AoD patients, because pain documentation in ED patients had been poor.[10,25]Additionally, the study did not use missing laboratory values or missing computer tomography (CT) scan interpretations as criteria for poor documentation as in previous studies,[12,26]since these values would not change the management of AoD patients. Finally, we were unable to assess many possible actionable reasons why documentations were poor. These reasons might probably be unfamiliarity with EMTALA statute, ED overcrowding, the cumbersome of transferring critically ill patients, etc.Identification of those actionable reasons could be obtained more readily from prospective observational or qualitative studies, as such, was beyond the scope of our retrospective study.

CONCLUSION

Documentation of clinical care and EMTALA compliance by emergency providers is poor. Inadequate EMTALA compliance documentation was associated with a higher likelihood of patients’ systolic blood pressure not meeting the AHA guideline recommendation at ED departure. Emergency providers should thoroughly document their care and ensure EMTALA compliance among this group of critically ill patients prior to transfer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Ms. Linda Kesselring for editing our manuscript.

Funding:This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-pro fit sectors.

Ethical approval:The Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Conflicts of interest:Authors have no financial or other conflicts of interest related to this submission.

Contributors:MR proposed the study and wrote the first draft.All authors read and approved the final version of the paper.

World journal of emergency medicine2019年2期

World journal of emergency medicine2019年2期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Keeping nephrotic syndrome on the emergency department edema differential: A case report

- Instructions for Authors

- A patient presenting painful chest wall swelling:Tietze syndrome

- Central nervous system manifestations due to iatrogenic adrenal insufficiency in a Ewing sarcoma patient

- Perceived effectiveness of infection control practices in Laundry of a tertiary healthcare centre

- Can an 8th grade student learn point of care ultrasound?