害虫的建筑

乔伊丝·黄/Joyce Hwang

黄华青 译/Translated by HUANG Huaqing

1 害虫

大卫·林奇导演的电影《蓝丝绒》的片头场景,展现了一个田园牧歌般的小镇,拥有成排的古朴住宅和苍翠的草地。随着镜头下摇至街道,眼前呈现的是一幅宁静祥和的景象:孩子在马路上嬉戏,消防员朝我们问好,在白色尖木篱的背后,一个男人正在给草坪浇水。然而,这种愉快的情绪随着男人突然摔在草坪上而陡然转变。当他中风般地痛苦挣扎,镜头不断拉近,拉近,但并未聚焦在男人身上,而是潜入一个未知的世界——草坪之中。在草坪中,画面呈现出阴暗、模糊的基调,成群昆虫发出的压抑而不断增强的鸣叫进一步渲染着这种氛围。草坪的恐怖之处逐步显露:这是一个人类迫切渴望控制的场所,然而却不断被自然的不可预知性所征服。尽管电影中的这个场景是以一种近乎梦境的基调来呈现的,但内嵌于此的是一个现世的、不断困扰着文明生活的问题。房地产经纪人、房主、园丁和农民都深知这一境遇——即处理“害虫”的噩梦现实。

但害虫究竟是什么?

对害虫的定义是极为矛盾的,取决于特定的语境。例如鸟类,对停车场和建筑壁架而言它们被视为害虫,但在鸟类展馆或野生动物保护区中却受到珍视。又如蝙蝠,它们是除害行动中最普遍的目标,被描绘为入侵老阁楼的狂暴吸血鬼;然而在农业和园艺业语境下,它们却是极受欢迎的捕食者,帮助消灭那些啃食植物的昆虫。

2 害虫构筑物

人类与害虫之间不断交锋的关系,随处体现于我们为这些动物、或以这些动物为主题设计的构筑物中。以鸟舍为例,最显而易见地展现了操作中的矛盾逻辑。一方面,精心搭建的鸟舍本身是当下流行的DIY热度的结果,时常传递出一种渴求之感。屡见不鲜的鸟笼套用了动物园似的“可爱”风格,是我们更大的已知世界的缩影。例如,鸟舍设计常常援引动画式的(人类)单户住宅造型,即双坡屋顶、前门、阳台、假烟囱以及入口坐垫1)。另一方面,驱赶鸟类的机制在城市建筑的营建中又无处不在。为了防止鸟类在可栖息的表面上徘徊,人们在窗台上安装成排的钢针,在装饰性架子外蒙上网帘,在屋脊铺设电网。我们去寻求职业咨询的帮助2)。在两种场景下,都可见对鸟类的控制和“捕获”。驱鸟装置显然是为了控制鸟类的实体存在——无论是通过驱赶还是消灭。较为含混的是鸟舍建造中体现的“捕获”形式。尽管它们并不像捕鸟器一样在实体意义上捕获鸟类,但却通过吸引它们进入我们设置的空间,来满足内心的捕获感。通过对人类居所的微缩呈现,鸟类也被归化为人类自身的微缩卡通形象。我们在为鸟类居所提供一处可预知、可见的场所的同时,也将它们置身于我们的凝视之下(想想观鸟者)。这种类型的“捕获”恰恰就是苏珊·桑塔格所讨论的摄影行为中的“掠夺性”。正如她在《论摄影》一书中写道:

摄影,是对被摄之物的挪用。它意味着在我们与世界之间建立某种联系,这感觉像是知识……[1]

就像车辆一样,相机也被作为一种掠夺性武器而售卖——一种尽可能自动化、随时准备弹射的武器……拍照的行为有着掠夺性的成分。给他人拍照,就是对他们的侵犯……相机将人们转化为一类可被象征性拥有的物件。[1]

我们对于蝙蝠的矛盾态度更为显而易见,同时潜藏着冲突。与通常被刻画得美丽而优雅的鸟类不同,蝙蝠往往被认为是恶毒、残暴而凶狠的。考虑到许多二次表现的倾向性,这一印象并不令人意外。除了阿尔弗雷德·希区柯克1963年的电影《鸟》之外,鸟类在影像记录中大多呈现出优雅崇高而神奇的形象。比如,《迁徙的鸟》(雅克·贝汉、雅克·克鲁奥德导演,2001)、《帝企鹅日记》(吕克·雅克导演,2005)和《飞禽传》(大卫·艾登堡禄拍摄的PBS系列纪录片,由BBC自然史部门制作,1998)[2]。

相反,蝙蝠往往出现在《德古拉》(托德·布朗宁导演,1931)这样的恐怖片中,或在万圣节卡片上与卡通化的鬼魂、巫师及黑猫共存。这种表达上的落差因我们无法真切地感知蝙蝠而被加强(也可能这是主要原因)。鸟类天生就在视觉和听觉上吸引人们的注意力。它们能轻易被看到、拍照、摄影和记录。它们的鸣叫能被理解,并在音乐创作中得到诠释。然而,蝙蝠在大自然中是难以捉摸的。它们只在夜晚出现,其鸣叫的频率无法为人耳察觉。可以说,由于我们无法看见或听见蝙蝠,不仅使我们对它的欣赏度降低,更致命的是引发了一种对未知的恐惧。

1 蝠塔/Bat Tower

人类倾向于无视那些看不见或无法感知之物。蝙蝠的生活基本上不为人类所察觉,因此也沦为被我们遗忘的对象。尽管它们是生态系统中重要的组成部分,发挥着授粉者及捕食者的积极作用(巧合的是,鸟类也从事相同“工作”),但它们的功劳在人类眼中几乎是不存在的。这种不可见度同样体现在人们为蝙蝠建造的大多数构筑物中。与致力于营造奇观和惊叹的鸟舍不同,蝙蝠舍(假设它被建造出来)的任务似乎只有两个:要么是进一步掩饰蝙蝠的存在,要么是将其归为一种功能型角色。前者情况下,很多蝙蝠舍在设计审美上都试图融入后院环境,有时会模仿住宅的装饰细节,或刷成临近树干的颜色。后者情况下,很多其他蝙蝠舍显露出一种平庸节俭的风格。尽管简化的DIY蝙蝠舍方案——例如那些由“国际蝙蝠保护协会”等重要组织提供的方案[3]——在初学者的个人建造中很有帮助,但它们的视觉存在感很难点燃公众对蝙蝠的兴趣。在两种情况下,不可见性始终存在。其一,通过采用一种消隐的建造美学[4],蝙蝠舍就和蝙蝠一起被推至人类感知的边缘;其二,鉴于我们对蝙蝠舍的设计及建造投入如此少的精力,也就在潜意识中表达出一种漠不关心的情绪——只不过是将蝙蝠舍建造视为环境保护者目标清单中的又一个勾选项而已。

3 害虫的可见性

以上讨论皆基于将蝙蝠视为害虫的微妙观念之上。然而我认为,蝙蝠这一物种的困境恰恰象征了人类与建成环境中诸多动物之间的矛盾关系。将这些所谓害虫“赶出视线,挥出大脑”的倾向是无处不在的。因此问题就在于,我们要如何与消隐、漠然的美学作斗争?我们如何构筑一个能够抵抗这种不可见性的“客观世界”3)——即一个具有物种特异性的环境?建筑具有提升物种可见度的潜力,可以藉由围绕其主体性设计的空间及构筑物,提升对这一物种的关注度。这篇文章反对将动物排除在感官之外,而关注如何将它们纳入设计建成环境的基本概念之中。

2 蝠云/Bat Cloud (©Sharon Li-Bain)

过去10年,越来越多建筑师和设计师开始将非人物种作为主体和服务对象进行设计。娜塔莉·杰里米琴科的高技派装置为飞蛾、蝾螈和鱼等动物带来新的主体性。弗里茨·海格的“动物庄园”系列项目将动物栖息地嵌入机构建筑中,以一种怪异的存在感唤醒人们对当下城市中动物空间之缺乏的关注。凯特·奥尔夫的“牡蛎建筑”项目在景观尺度上激发起人们对物种的好奇心,同时也指向水体污染等更大挑战。我设计的若干装置项目,如“蝠塔”(图1)、“蝠云”(图2)、“荫蔽所”(图3)等,运用了“奇观”策略,试图唤起对环境中动物空间的关怀。这些项目并未选择默默消失(并延续消隐的美学),而是探索了形式及感知上的设计策略,以提升人类对于一个既定事实的认知——我们与其他物种一起共享这个地球。

本文中,我将在更本质的层面对“包容性”概念进行反思,进而拓展如何借助建筑提升物种“可见度”的观点。接下来的讨论包括一系列项目,它们将潜在的动物栖息地直接引入人类居住环境的建筑构件之中。通过重新审视墙体、基础、屋顶等传统建筑构件的性能和影响,这一策略试图解决一个即便在对生物友好构筑物的兴趣越发浓厚的时代依然徘徊不去的棘手争论。将其他物种以较高的亲密度接纳入我们建造的世界中,依然是个广受争议的论题。尽管城市居民整体上能理解在建成环境中提升生物多样性的生态意义,但人类还是倾向于将动物排除在生活场域之外。当我们在建筑中遭遇到动物,最常见的反应或许就是想办法将其赶走,并通过各种方式阻止它们进入,例如用金属网遮蔽通风口。当然,这一类藉由“调整”“修理”等方式的增量型操作被视为可行的策略,甚至被吹捧为“最好的方法”。接下来这些项目的讨论,我希望转而思考另一种纳入物种多样性的方式,从而导向一种更深刻的建筑形式。一旦我们能够超越修理建筑漏洞的观念,便学会将权力赋予更多元化的群体,由此以一种更加触及本质的方式重新构思所处的建成环境。

4 构件作为空间类型:重审墙体、窗、屋盖/阁楼、基础和屋顶

4.1 墙体

3 荫蔽所/Bower

从一个名为“害虫墙”(图4)的概念方案出发,“巢墙”(图5)是一个墙体原型结构,将蝙蝠和鸟类栖息地融入设计,目的是为物种特殊性的考量赋予一种空间和材质实体。这个原型结构由杉木、松木和回收材料建成,其主要特征包括供蝙蝠栖息的狭长缝隙空间,而蝙蝠通常栖息在阁楼、墙缝及其他建筑部件中。采用回收窗百叶等粗糙切割的木材及质感明晰的材料,是为了让蝙蝠更轻易地着陆,并爬进上方的空穴。层叠堆积的木材能在白天吸收过多的热量,提供更好的隔热及保暖持久性,这对蝙蝠的栖息而言十分重要。这个原型结构也融入了供鸟类筑巢的盒子和表面,是为燕子或其他栖居在崖壁上的鸟类而设置的。在这个项目中,我们提出的问题是:既然外墙已是个可栖居的表面,那么如何将这种特性变得可见,并在美学上予以强化?一面墙体能否不仅作为立面,也可经过设计发挥出活态细胞膜的作用?

4.2 窗户

“防误撞区”(图6)项目针对城市区鸟类死亡的最主要原因:与玻璃相撞。飞行中的鸟往往很难分辨透明玻璃和露天环境,尤其是当玻璃反射着天空、树木或建筑周围环境的其他元素。如今,我们看到越来越多的组织机构开始关注这个很少被察觉的杀戮狂欢。奥杜邦协会、美国鸟类保护协会等爱鸟团体最早发起了这样的项目,与研究者合作开发对鸟类安全有益的城市建筑导则,并出版了相关报告,帮助建筑师、开发商和房屋业主在决定窗户设计的过程中做出更周全的选择。制造商开始制造一些防止鸟类误撞的建筑材料和体系,从窗玻璃贴纸(类似于我们人类为了更好地“看见”玻璃推拉门而使用的方式)到印花、烧釉玻璃,试图加强视觉“干扰”以防止鸟类选取那条可能致命的飞行路线。在关于建筑的可持续性评估体系中(它通常很少关注动物保护),美国绿色建筑委员会(USGBC)提出了一项LEED试点评分法,以评估“鸟类防撞性能”。

在生态-城市的两难境遇之中,我们看到这些利益冲突之间一个越发值得探索的领域。如果建筑窗户真的被认为是城市鸟类的第一号连环杀手,那么我们如何在不妨碍窗户的观景和采光功能的前提下,重新考虑玻璃窗的设计呢?我们如何为玻璃设计视觉上的干扰图样,而不破坏现代主义建筑所憧憬的透明性?我们如何兼顾非人类物种的主体性,同时又确保和提升人类从室内窥视室外的愿望?

1 Pests

The opening scene of the film Blue Velvet,directed by David Lynch, shows an idyllic small town, with rows of quaint houses and lush green lawns. As the camera pans down the street, we are encountered with depictions of wholesome goodness:children crossing the street, a fi reman waving hello,white picket fences, and a man watering his lawn.The gleeful mood changes however, when the man suddenly collapses on the lawn. As he is struggling with what appears to be a seizure, the camera zooms closer and closer, focusing not on the man, but diving into a world of the unknown: the lawn itself. Zooming into the grass, the film reveals an atmosphere of darkness and uncertainty, intensi fi ed by muラed and increasingly louder sounds of swarming insects. The horror of the lawn is revealed: it is an artifice that human beings desperately attempt to control, yet it is continually being overtaken by the unpredictability of nature. Although this scene in the fi lm is depicted in an almost dream-like state, embedded within it is a mundane yet incessant problem frequently associated with civilised living. A condition known well by building managers, homeowners, gardeners, and farmers, it is the nightmarish reality of dealing with"pests."

But what exactly is a pest?

The very de fi nition of a pest is highly con fl icted and always contingent upon its specific context.Birds, for example, are considered to be pests in the context of parked cars and building ledges; but they are treasured in aviaries or wildlife preserves. Bats,a most popular target of pest removal practices,are depicted as rabid vampires who unwelcomingly invade old attics; however, in the context of farming and gardening, they are highly desirable as natural predators of plant-eating insects.

2 Pest artifacts

Our embattled relationship with pests is ubiquitously present in the artifacts that we construct for and of these animals. Perhaps a consideration of bird inhabitations most clearly shows these conflicting logics at play. On the one hand, carefully-crafted birdhouses – a popular resultant of do-it-yourself aspirations – often project an attitude of desire. All too frequently,they resonate with menagerie-like "cuteness,"a miniaturisation of our larger, known world.Birdhouse designs, for example, draw from cartooned representations of single-family (human)houses, complete with pitched roofs, front doors,balconies, fake chimneys, and welcome mats1). On the other hand, bird-deterrent mechanisms are ubiquitously incorporated in the construction of urban buildings. To prevent birds from loitering on perch-able surfaces, we implement rows of needle-sharp steel spikes on window sills and ledges; we drape nets over decorative molding; we install rows of electrified wire along roof edges.We seek professional consultants2). The control and "capture" of birds can be evidenced in both scenarios. Bird deterrent devices clearly control the physical presence of birds – either by repulsion or by extermination. Less obvious is the form of"capture" that is exerted through the construction of birdhouses. While they do not physically capture birds in the way that birdcages do, birdhouses allow us to ful fi ll a sense of capture by drawing them into our space. Through the miniaturised representation of our own habitations, birds, too, are also relegated to the status of cartooned miniatures of ourselves.By providing a predictable and visible place for bird inhabitation, we are also subjecting them to our gaze(think: birdwatchers). This type of "capturing" is precisely what Susan Sontag describes in discussing the "predatory" act of photography. As she writes in her book On Photography:

To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge…[1]

Like a car, a camera is sold as a predatory weapon – one that's as automated as possible, ready to spring… there is something predatory in the act of taking a picture. To photograph people is to violate them…; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed.[1]

4 害虫墙/Pest Wall

5 巢墙/Habitat Wall

6 防误撞区/No Crash Zone

7 共居/Co-Occupancy

“防误撞区”是对卡尔森·皮里·斯科特楼窗户的临时“整修”,试图让防鸟类误撞的措施显现出来,同时确保建筑中人文主义话题的预设。

在兼顾建筑窗户周边瓷砖样式的同时,这个项目通过图样装饰来创造视觉扰动,使其发挥超出美学构成的作用。这个装置明显借鉴了文艺复兴式的一点透视,以及如像素化伪装这样的当代视觉操作手段,由此也涉足了人类视觉的根本建构。

4.3 基础与屋盖/阁楼

“共居”(图7)是一个概念方案,力图让野生动物栖息地融入人类建成环境。为了提升人们对于城市生态重要性、人与非人类物种关联性的关注,这个设计纳入了为植物和动物设置的条形区,使其与人类居住区共存。例如蝙蝠、鸟类,安置在可扩展的、体块式的屋顶构筑物中。这些构筑空间具有不同的尺度及保温效果,但都是有遮蔽并容易进入的,提供了筑巢的空穴及栖息的结构。蛇、蝾螈及其他类似生物则占据了加厚的“基础”,这个“基础”采用铁丝笼结构,以承载密垒的大块卵石及石块。作为一项初步的设计,这个项目以跨物种共居的概念重新界定了屋顶、基础等基本建筑元素,并提出了新的空间、视觉及材质方式,来重构我们的建成环境。

4.4 屋顶

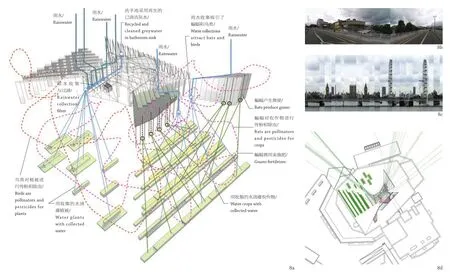

“共栖”(图8)是为人类与动物共同设计的屋顶栖居地,重新思索了城市屋顶的潜能。人类栖居的空间被设置在一系列城市野生动物的栖息结构之间,这些结构专门设计来吸引和容纳鸟类和蝙蝠。这些动物作为天然的授粉者和“杀虫剂”,将促进屋顶谷物和其他植物的生长。这个项目使人们有机会看到鸟类筑巢、蝙蝠捕食蚊子的过程(由此也为人提供了天然的除蚊措施),可作为城市自然休闲爱好者的一项体验。从项目的室内空间中,人类居住者可以更清晰地观察周边环境。项目设计了一个由反射镜面百叶组成的幕墙体系,将有选择性地调节看向城市的视线。这些镜面通过使城市天际线变得碎片化以及创造视觉重复的方式——比如让同一个标志性建筑反射重复多遍,提升人们对城市环境的关注度。此外,蝙蝠和鸟类的存在感,随着它们往返于巢穴内外的飞行,将藉由这一反射系统在视觉上得到强化。“共居”挑战了人们习惯上假定的人与动物、室内与室外的二分对立关系。我们将项目构想为一个微生态系统,由自然与建成主体/环境之间一系列相互依赖的流动来呈现。

5 结论

将我们设计的城市空间与动物共享,是一种矛盾的情绪。一方面,在公园和后院中鸟类通常是受欢迎的,从鸟类喂食器的数量和品类之多就不难看出。而另一方面,鸟类留下的痕迹和污垢又使它们成为入侵人类领地的“烦心事”。当动物及其他非人物种穿越我们为之构筑的边界,就会被认定为“不得其所”,进而被视为“害虫”。因此最紧迫的问题就是:我们如何将动物的存在重置于一个更具建设性的舞台?如上文所讨论的,建筑与设计拥有在多个尺度激发大胆应答、纳入多元物种的能力。在最基本的层面,建筑可以建立一系列环境条件,为物种的栖息提供前提。而另一层面,将这些条件编织起来,能满足人类的惊叹感和好奇心。“害虫建筑”并不将“虫害控制”作为一个需要解决的问题。相反,它提出建筑所激发的共鸣——无论是视觉、空间、材质、生态或是社会层面——能够促进更加广义的“包容性”目标。这就超越了“控制”任何物种数量的有限任务,而迈入一个更为切中要害的策略,以合作性态度介入我们所处的生态系统。“害虫建筑”全身心地参与投入动物间的冲突逻辑——一端是可预见性,另一端是渴求感。如此,它就成为促使人们重新思索“害虫”这一矛盾定义的引线。“害虫建筑”通过强化所谓害虫的存在感,最终可视为一种借助反思性的可视化过程而转变顽固观念现实的工具。□

注释/Notes

1)案例见Yard Envy/For example, see Yard Envy.[2018-06-09]. https://www.yardenvy.com/bird-houses.asp.

2)案例见Birds Away/For example, see Birds Away.[2018-06-09]. https://www.yardenvy.com/bird-houses.asp, (accessed June 9, 2018).

3)雅各布·冯·尤克斯卡尔描述道,两个不同物种可能存在于相同的总体环境中,但各自寻求的是完全不同的特殊环境。他列举了壁虱和鹿的例子:适于壁虱的环境条件不同于鹿的,尽管它们存在于同一个环境中(森林)。(见参考文献[5])/Jakob Von Uexkull describes that two different species might exist in the same general environment, but each require completely different speci fi c environments. He uses the example of the tick and the deer: the conditions that matter to a tick are different than those that matter to a deer even though occupy the same environment (the forest). (See reference [5])

参考文献/References

[1] Susan Sontag. On Photography. New York: Farrar,Straus and Giroux, 1989:3-24.

[2] David Attenborough. The Life of Birds. [2018-06-09]. http://www.pbs.org/lifeofbirds/.

[3] Get Involved / Install a Bat House//Bat Conservation International. [2018-06-09]. http://www.batcon.org/index.php/get-involved/install-a-bathouse.html.

[4] Paul Virilio. Steve Redhead ed. The Paul Virilio Reader. New York: Columbia University Press,2004:57-81.

[5] Jakob von Uexkull. A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans. Minneapolis, London:University of Minnesota Press, originally published 1934 by Verlag von Julius Springer.

Our conflicted attitude toward the presence of bats is even more pronounced and layered with contradictions. Unlike birds, which are often admired as beautiful and graceful creatures,bats are typically understood as vicious, rabid,and monstrous. This is not a surprise, given the tendencies of mediated representation. With the exception of Alfred Hitchcock's 1963 fi lm, The Birds,birds are typically documented and exhibited with a sense of gentle awe and wonder. Simply examine the list of bird-driven documentaries. To name a few,consider: Winged Migration (directed by Jacques Perrin and Jacques Cluzaud, 2001), March of the Penguins (directed by Luc Jacquet, 2005), and The Life of Birds (a PBS series by David Attenborough,produced by the BBC Natural History Unit, 1998)[2].

Bats, on the other hand, are more often depicted in horror films such as Dracula (directed by Tod Browning, 1931) or alongside cartooned ghosts, witches, and black cats on Halloween cards.This rift in representation is further enhanced (or perhaps caused) by our lack of ability to tangibly sense bats. By nature, birds attract attention,both visibly and audibly. They are easily spotted,photographed, filmed and recorded. Their songs are audibly understood and interpreted in musical compositions. Bats, however, are elusive by nature.They emerge at night and chatter at frequencies inaudible to the human ear. One could argue that our inability to see or hear them not only contributes to a lack of appreciation, but more poignantly contributes to a fear of the unknown.

Humans have a tendency to dismiss that which they cannot see or sense. Bats go about their lives relatively unnoticed by humans, and as such, they fall victim to our tendency toward forgetfulness.Although they are critical components of our ecosystem, functioning actively as pollinators and natural predators (incidentally, the same kind of"work" performed by birds), their efforts often remain invisible to the human population at large.This sense of invisibility is hardly resisted by the artifacts we construct for bats. Unlike birdhouses,which seem to intensify a sense of spectacle and wonder, bat houses (if even implemented at all)seem to accomplish one of two tasks: Either they further camouflage the presence of bats or they relegate the bat to a role of utilitarian function.Regarding the former, many bat houses are designed to aesthetically blend into backyard environments,sometimes mimicking the decorative trim of a house or painted to match the colour of a nearby tree bark. With regard to the latter, many other bat houses tend to project an attitude of banal economy.While simpli fi ed do-it-yourself bat house plans – for instance, those provided by signi fi cant organisations such as Bat Conservation International[3]–are indeed helpful in jump-starting individual efforts to construct more bat houses, their visible presence does little to fuel public interest. In both cases, invisibility is perpetuated. First, through constructing an aesthetic of disappearance[4], bat houses – and therefore bats – are pushed to the margins of human conscience. Second, by projecting little or low effort into the design and construction of bat houses, we subconsciously also project an aesthetic of indifference – that is, one which relegates bat house construction to yet another item on the to-do list of environmental stewardship.

3 Pest visibility

The discussion at this point has hinged on nuanced perceptions of bats as pests in particular, but I would argue that, as species, their plight is emblematic of the con fl icted relationships that humans have with animals in the built environment. The tendency to push these so-called pest species "out of sight, out of mind"is pervasive. A question therefore is: how do we combat the aesthetics of disappearance and indifference? How do we craft an "umwelt"3)– that is, a species-speci fi c environment – that resists a condition of invisibility?Architecture has the potential to increase species'visibility, to bring attention to animals through the spaces and artifacts that we design with their subjectivity in mind. Rather than excluding animals from our consciousness, this article focuses on how we can include them in a fundamental conception of the designed environment.

The past decade has seen a proliferating web of architects and designers who are working in considering non-human species as subjects and agents of design. Natalie Jeremijenko's technologically-embedded installations brought a new sense of subjectivity to moths, salamanders,and fi sh, for example. Fritz Haeg's "Animal Estates"project series projected animal habitats into institutions, with a strangeness of presence that brought an increased awareness of the lack of animal spaces in cities. Kate Orff's "Oystertecture" project instigated curiosity about species at the scale of landscape, while addressing larger challenges such as water pollution. Several of my installation projects,as well, such as Bat Tower (Fig.1), Bat Cloud (Fig.2),and Bower (Fig.3), also deploy tactics of "spectacle"to bring increased attention to the space of animals in the environment. Rather than fading quietly (and perpetuating the aesthetics of invisibility), these projects explore formal and perceptual design tactics to increase human consciousness of the fact that we share the world with many species.

In this article, I will expand on the notion of increasing "visibility" of species through architecture, by re fl ecting on the idea of "inclusion"in a more fundamental way. The following discussion includes a series of projects that introduce potential habitat conditions directly into the building components that make up the environments that we ourselves occupy. By reconsidering the performance and resonance of conventional building components – such as wall,foundation, and roof – this tactic begins to address a prickly issue of contention that still lingers, even with the growing interest in introducing speciesfriendly structures. The acceptance of species within close proximity to our own constructed world is still an embattled debate. While urban citizens generally tend to understand the ecological signi fi cance of increasing biodiversity in the built environment, our tendency as human beings is to consider animals as external to our spheres of living. Perhaps the most common response to encountering animals in buildings is to fi nd a way to remove them, to exclude them with various methods, such as covering ventilation holes with metal wire mesh. Certainly, these ways of working incrementally – through tactics of "tweaking"and "fixing" – are recognised as viable solutions,and even touted as "best practices." With the discussion of the following projects, I would like to instead speculate on another way to allow the multiplicity of species to move us toward a more poignant form of architecture. Once we are able to think beyond notions of fixing buildings, we can start to reimagine the built environment in a more fundamental way, by giving agency to a more collective population.

4 Components as spatial types: reconsidering the wall, window, roof/attic, foundation, and rooftop

4.1 Wall

Drawing from a speculative proposal titled “Pest Wall" (Fig.4), "Habitat Wall" (Fig.5) is a prototype wall structure that incorporates conditions for bat and bird inhabitation into its design, aiming to give a spatial and tactile presence to speciesspeci fi c considerations. Built from cedar, pine, and salvaged building materials, the prototype's primary features include thin crevices of space which allow for occupation by bats that typically might roost in attics, wall cavities, and other building features.Use of rough cut wood and textured material, such as recycled window shutters, enable bats to better land and climb into the cavities above. The layering and mass of the wood helps absorb heat during the day and provides better insulation and thermal consistency, which is important for bat dwellings.The prototype also includes bird nesting boxes and surfaces that are constructed for swallows and other cliff dwelling birds. In this project, we ask: If an exterior wall is already an inhabitable surface,how can those conditions be made visible, and aesthetically intensified? How can a wall not only act as a façade but also be designed to perform as a living membrane?

4.2 Window

"No Crash Zone" (Fig.6) is a project that addresses the most significant cause of bird mortality in urban areas: collision with glass.Birds in flight are often unable to distinguish clear glass from open air, particularly if the glass is reflecting sky, trees, or other elements around a building’s contextual environment. Today we see a growing number of organisations that are beginning to address this under-acknowledged killing spree. Bird advocacy groups such as The Audubon Society and the American Bird Conservancy are spearheading initiatives by working with researchers to develop bird-safe building guidelines for cities and are publishing reports to assist architects, developers, and building owners to make more informed decisions about window design. Manufacturers are beginning to produce building materials and systems to prevent bird collisions, ranging from window decals (similar to those that we humans deploy to better "see"a glass sliding door) to patterned, fritted glass –intended to add visual "interference" to deter birds from what would be otherwise deadly flight paths. In the realm of sustainability assessment metrics for buildings – which has not typically focused on animal conservation – the USGBC has initiated a LEED Pilot Credit for testing "Bird Collision Deterrence."

In this eco-urban dilemma, we see an emerging territory for exploration among these conflicts of interests. If indeed building windows have been deemed as the #1 serial killer of urban birds,how then can we reconsider the glass window in a way that does not remove its function as an aperture for view and light? How can we design visual interference patterns into glass without undermining Modernism's dream of transparency?How can we consider the subjectivity of non-human species, while still enabling and enhancing human desires, such as views from inside out?

"No Crash Zone" is a temporary "renovation" of a window in a Carson, Pirie, Scott Building to make visible the logics of bird-strike prevention while still aspiring toward architecture's preoccupations with the humanist subject.

With a nod to the tiling pattern framing the building's windows, the project aims to create visual noise through the deployment of graphic ornament, reconsidering its role beyond agendas of aesthetic composition. The installation also taps into the fundamental construction of human vision by overtly referencing the one-point Renaissance perspective, as well as more contemporary optical tactics such as camou fl age through pixilation.

4.3 Foundation and roof/attic

"Co-Occupancy" (Fig.7) is a speculative project that aims to incorporate wildlife habitat into the built environment. In an effort to draw attention to the critical importance of urban ecologies, and our interconnectedness with non-human species,the design includes delineated zones for fl ora and fauna, as well as zones for human occupancy. Bats and bird, for example, could live in expanded,volumetric roof conditions. These are conceived as sheltered but accessible spaces of varying dimensions and degrees of insulation, with cavities for nesting, and structures for perching. Snakes,salamanders, and similar creatures could occupy a thickened "foundation" condition, composed of a structural mesh cage that is formed to hold closelypacked masses of boulders and large rocks. As a primary agenda, this project imagines fundamental architectural components – such as roof and foundation – in terms of cross-species occupancy,and begins to suggest new spatial, visual, and tactile ways to reconsider our constructed environment.

4.4 Rooftop

"Co-Habitat" (Fig.8) is a speculative roof habitation for humans and animals that reconsiders the potential for urban rooftops.Human occupancy spaces are situated between and along a series of urban wildlife habitation structures, designed particularly to attract and accommodate birds and bats. As natural pollinators and "pesticides," these animals would stimulate the growth of rooftop crops and other vegetation over time. With potential opportunities to see birds nesting or bats hunting for mosquitoes(consequently providing a natural means of mosquito-abatement for humans), this project is an experience for recreational enthusiasts of urban nature. From the project's interior spaces,human inhabitants will become extra-aware of their surrounding environment through vision.The project proposes a wall system composed of mirrored-louvers that would mediate selected views toward the city. The effects of these mirrors would draw attention to the urban context by fragmenting the skyline, as well as creating visual repetitions, for example situations where one sees the same iconic building reflected multiple times. Additionally the presence of bats and birds, as they fl y in and out of their nesting sheds,would be visually intensified through this system of reflections. Co-Habitat challenges typically assumed dichotomies and relationships between humans/animals and inside/outside. The project is envisioned as a micro-ecosystem staged as a series of interdependent fl ows between natural and constructed agents/environments.

5 Conclusion

The sentiment of sharing our designed urban spaces with animals is a conflicted one. On the one hand, the occupation of birds in parks and backyards is generally desirable, as exemplified by the quantity and variety of bird feeder types.Yet on the other hand, the traces and debris left by birds render them instead as "nuisances,"trespassing on our territory. When animals –and other species – transgress our constructed boundaries around them, they are judged to be"out of place," and as such, are characterised as"pests." The pressing question, therefore, is: how can we recast the presence of animals in a more constructive light? Architecture and design, as I discuss, has the capacity to inspire bold responses at multiple scales and involving multiple populations. At a basic level, architecture can set up a number of environmental circumstances provide habitat conditions for species. At another level, the act of choreographing these circumstances can begin to generate experiences of wonder and curiosity for human beings as well.Pest Architecture does not tackle "pest control" as a problem to solve. But it argues that architecture's production of resonance – whether visual, spatial,tactile, ecological, or social – can begin to address a much broader aim of "inclusion". This moves beyond the finite task of "controlling" any speci fi c animal population and rather, heads toward a more poignantly-conceived strategy for engaging collaboratively with our contemporary ecosystems.Pest Architecture revels in working through the conflicting logics toward animals – between predictability, on the one hand, and a sense of desire, on the other. In this way, it is a catalyst for rethinking the conflicted definition of "pest." By magnifying the presence of so-called pests, Pest Architecture ultimately is a means of transforming the stubborn reality of opinion through a process of re fl ective visualisation.□

项目信息/Credits and Data

1 蝠塔/Bat Tower

由大草原之蚁工作室的乔伊丝·黄主持。项目的设计和施工由纽约州艺术委员会的“独立项目资金”和范阿伦协会的项目赞助支持;装置由纽约州大学职业联合会的“努阿拉·麦根·德雷舍尔博项目”资助。/Project by Joyce Hwang/Ants of the Prairie. Design and construction made possible with an Independent Projects Grant from the New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA) and the Van Alen Institute as the project's Fiscal Sponsor; Installation made possible with a grant from the New York State/United University Professions' Dr. Nuala McGann Drescher Programme.

团队成员/Team: Thomas Giannino, Micahel Pudlewski,Laura Schmitz, Nicole Marple, Mark Nowaczyk

顾问/Consultants: 生物学/biology: Katharina Dittmar;结构工程/structural engineer: Mark Bajorek; 施工/construction: Richard Yencer(布法罗分校建筑与规划学院材料与工艺工作室/UB School of Architecture and Planning Materials and Methods Shop)

2 蝠云/Bat Cloud

由大草原之蚁工作室的乔伊丝·黄主持,是布法罗分校人文学院“流动文化”系列活动的一部分。感谢布法罗分校建筑与规划学院的支持。/Project by Joyce Hwang/Ants of the Prairie. The project was designed and built as part of the University at Buffalo Humanities Institute's"Fluid Culture" Event Series. Thanks also to the UB School of Architecture and Planning for support.

“流动文化”组织者/Fluid Culture Organisers: Colleen Culleton, Justin Read

团队成员/Team: Sze Wan Li-Bain, Mikaila Waters, Robert Yoos

顾问/Consultants: 结构工程/structural engineering: Mark Bajorek; 生物学/biology: Katharina Dittmar; 蒂夫特/布法罗科学博物馆协调人/Tifft/Buffalo Musuem of Science coordinators: Lauren Makeyenko, David Spiering

3 荫蔽所/Bower

由乔伊丝·黄、Ellen Driscoll以及Matthew Hume主持,City as Living Laboratory and Artpark委托设计和建造。/Project by Joyce Hwang and Ellen Driscoll, with Matthew Hume.Commissioned by City as Living Laboratory and Artpark.

经济学/生物学顾问/Ecology/Biology Consultants:Katharina Dittmar, Heather Williams

施工助手/Construction Assistants: John Costello, John Wightman, Olivia Arcara

结构顾问/Structural Consultant: Mark Bajorek

项目在布法罗分校建筑与规划学院的支持下得以建成。/Project made possible by the University at Buffalo, School of Architecture and Planning.

4 害虫墙/Pest Wall

由大草原之蚁工作室的乔伊丝·黄主持。/Project by Joyce Hwang/Ants of the Prairie.

5 巢墙/Habitat Wall

由大草原之蚁工作室的乔伊丝·黄主持。芝加哥艺术学院沙利文画廊“外部设计”委托,其馆长为Jonathan Solomon。设计与制作还获得了麦克道尔文艺营、布法罗分校SUNY建筑与规划学院以及纽约艺术基金会的支持。/Project by Joyce Hwang/Ants of the Prairie. Project commissioned by School of the Art Institute of Chicago,Sullivan Galleries for "Outside Design," curated by Jonathan Solomon. Design and fabrication made possible with additional support from The MacDowell Colony, University at Buffalo SUNY School of Architecture and Planning, New York Foundation for the Arts.

施工合作者/Construction Collaborators: John Costello,Kenzie McNamara, Joey Swerdlin, Duane Warren, Alex Poklinkowski

顾问/Consultants: Katharina Dittmar, Mark Bajorek

6 防误撞区/No Crash Zone

由大草原之蚁工作室的乔伊丝·黄主持。芝加哥艺术学院沙利文画廊“外部设计”委托,其馆长为Jonathan Solomon。/Project by Joyce Hwang/Ants of the Prairie.Project commissioned by School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Sullivan Galleries for "Outside Design," curated by Jonathan Solomon.

装置管理/Installation Manager: Christina Cosio, Sullivan Galleries

7 共居/Co-Occupancy

由大草原之蚁工作室的乔伊丝·黄主持。在麦克道尔文艺营建造。/Project by Joyce Hwang/Ants of the Prairie.Created at the MacDowell Colony.

8 共栖/Co-Habitat

由大草原之蚁工作室的乔伊丝·黄主持。2010年由Living Architecture 和 Artangel主办的“伦敦的一间房”竞赛作品。/Project by Joyce Hwang/Ants of the Prairie.Created for "A Room for London" Competition, by Living Architecture and Artangel, 2010.