基于静息态功能成像的遗忘型轻度认知障碍患者核心脑网络变化研究

冯琪,毛德旺,王玫,廖峥娈,于恩彦,袁建华,丁忠祥*

遗忘型轻度认知障碍(amnestic mild cognitive impairment,aMCI)是指不满足痴呆标准的老年个体中一定程度的记忆力下降和认知衰退,被认为是阿尔茨海默病(Alzheimer's disease,AD)的前驱阶段[1]。在AD及aMCI阶段不仅有脑结构的改变,重要的还有脑功能的变化。许多基于静息态fMRI(resting-state fMRI,rs-fMRI)分析的研究结果表明,在MCI阶段中可以观察到低频振幅的变化[2-3]以及局部一致性技术所揭示的功能连接(functional connection,FC)的改变[4]。这些技术多聚焦在对局部脑区的研究,我们知道人类大脑功能是一个整合的网络系统,单个体素或局部脑区的变化不能完全解释整体脑功能的异常。

2011年,Menon[5]提出了包括默认网络(default-mode network,DMN)、突显网络(salience network,SN)和执行控制网络(executive control network,ECN)在内的“三网络模型”概念。这三个核心脑网络密切交互,在调节人类认知和情感状态方面发挥着重要的作用。但到目前为止,尚未见明确影像学证据解释AD及aMCI中三个核心脑网络之间的定向关系。

格兰杰因果性分析(Granger causality analysis,GCA)是一种研究一个脑区中时间序列的过去值是否可以基于多重线性回归正确地预测另一脑区当前值的方法。最近,Zang等[6]提出使用来自线性回归的符号路径系数来测量脑区之间的有向功能连接相互作用。Miao等[7]使用GCA来识别AD患者DMN中心的异常连接模式。左右大脑半球起源相同的神经元内源性自发活动高度相似,即功能同伦[8],基于体素-镜像同伦连接(voxelmirrored homotopic connectivity,VMHC)可用于检测大脑内源性功能构造的特征,用于反映半球间的信息交流整合。

在本研究中,我们使用VMHC和GCA技术分别测定AD、aMCI和健康对照(healthy controls,HC)组的无向和有向功能连接指数,并研究了三组中三个网络之间无向和有向功能连接的变化。本研究的重点是寻找aMCI患者的核心脑网络变化指标,以达到早期诊断aMCI的目的。

1 材料与方法

1.1 一般资料

对2012年7月至2014年6月在浙江省人民医院的记忆专科门诊就诊的AD和aMCI患者进行前瞻性研究。HC组选取的是医院健康促进中心登记的志愿者。所有参与者都是右利手,并签署了书面知情同意书。所有申请程序均经过浙江省人民医院伦理委员会批准。

所有受试者均接受标准的痴呆筛查,使用简易智能精神状态量表(mini-mental state examination,MMSE)和蒙特利尔认知评估量表(Montreal cognitive assessment,MoCA)评估受试者的神经心理学表现。AD患者符合“美国国立神经病学、语言障碍及卒中研究所和阿尔茨海默病及相关疾病协会(NINCDS-ADRDA)”诊断标准[9]。aMCI组的所有入组被试均符合aMCI的临床诊断标准[10]。排除标准:脑卒中、脑外伤、引起记忆受损的其他神经系统疾病(如脑肿瘤、帕金森病、癫痫等);系统性疾病(如严重贫血、高血压、糖尿病等);精神疾病史。HC组的入组标准:没有神经或精神疾病;没有神经缺陷(如视觉或听力丧失);常规颅脑MR图像上无梗死或局灶性病变;没有认知功能障碍;MMSE评分≥28分;MoCA评分≥27分。

1.2 检查方法

采用德国Siemens Trio 3.0 T MR扫描仪进行MRI数据采集。首先采集常规MRI序列,包括常规T1WI、T2WI、FLAIR、DWI序列。再使用平面回波成像(echo-planar imaging,EPI)序列采集静息态功能图像:共33层,层厚3.5 mm,层距0.7 mm,矩阵64×64,TR 2000 ms,TE 30 ms,反转角90°,扫描野(FOV) 220 mm×220 mm,时长7 min。所有的被试者要求在扫描过程中放松、闭眼、静止不动,并避免任何有结构的思维活动。

1.3 功能数据的预处理

使用基于统计参数图(SPM) 8软件包(http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm)的DPARSFA v2.3软件(http://rfmri.org/DPARSF)和REST v1.8软件(http://www.restfmri.net)对fMRI数据进行处理。预处理包括以下步骤:去除前四个时间点、层面时间差校正、头动校正、空间标准化到蒙特利尔神经科学研究所(Montreal neurological institute,MNI)标准空间、用高斯核(FWHM 6 mm)进行空间平滑、带通滤波(0.01~0.08 Hz)、去线性漂移、回归无关信号(包括全脑信号、白质和脑脊液的时间序列和六个仿射运动参数)。过度头动的排除标准为任何方向上平移大于2.0 mm或旋转大于2.0°。

1.4 镜像同伦功能连接

笔者采用了Kelly等[11]的计算方法来研究VMHC。检测了VMHC中大脑半球和脑区的组间差异。通过单侧半球灰质掩模内所有体素的平均VMHC值来计算全局VMHC (每对同源连接只有一个相关性)。使用FSL (阈值为25%组织类型概率)的MNI152灰质组织创建掩模。笔者排除了x=±4的内侧体素,以最小化中线上人工增加的VMHC。

1.5 GCA分析

参照先前的GCA研究[12-14],将DMN的感兴趣区(region of interest,ROI)设置在后扣带回(posterior cingulate cortex,PCC)处,以(x=0,y=-53,z=26)为中心。SN的ROI设置在背侧前扣带回(dorsal anterior cingulate cortex,dACC),以(x=-6,y=18,z=30)为中心。将ECN的ROI设置在背外侧前额叶皮层(dorsolateral prefrontal cortex,dlPFC),以(x=30,y=12,z=60)为中心。在获得每个受试者的GCA图后,通过去除全脑平均值并除以全脑标准差进行标准化。

1.6 统计学分析

使用单因素方差分析来比较AD、aMCI和HC组中的年龄、受教育水平和简易智能精神状态量表评分。由于HC组没有进行MoCA评分,笔者使用双样本独立t检验比较AD和aMCI之间的MoCA评分差异。使用Fisher精确检验检查性别比。P<0.05被认为具有显著统计学差异。采用单因素方差分析评估三组受试者VMHC和GCA所检测的潜在组间差异。多重比较校正使用了AlphaSim工具(http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/pub-/dist/doc/manual/AlphaSim.pdf),进行蒙特卡洛模拟确定簇大小,达到P<0.05的校正显著性阈值。为了进一步研究组间差异,将在上述单因素方差分析中显示显著差异的脑区设置为ROIs。ROIs是以峰值体素为中心,半径为6 mm的球体。从ROIs中提取平均VMHC和GC值,并对每个ROI进行双样本t检验以用于组间比较,采用Bonferroni校正,P值设定在0.05/3的显著性水平。

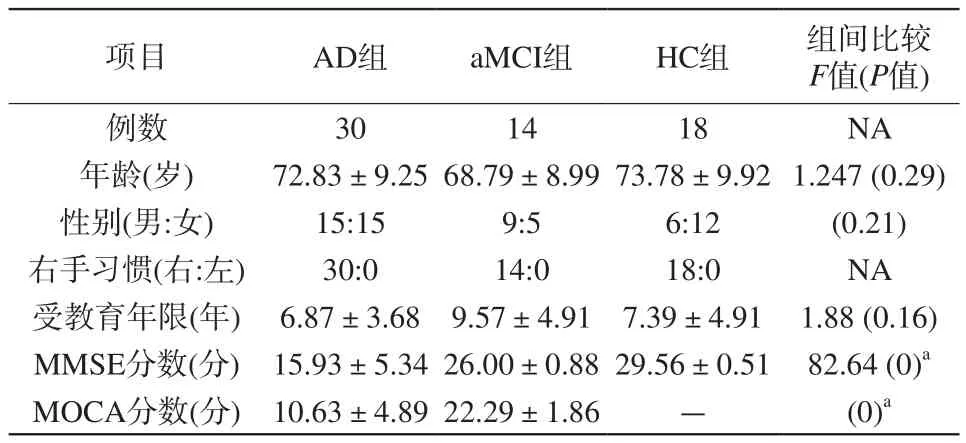

表1 AD、aMCI和健康对照的人口统计学和神经心理学表现Tab. 1 Demographics and neuropsychological performances of the AD, aMCI and healthy control

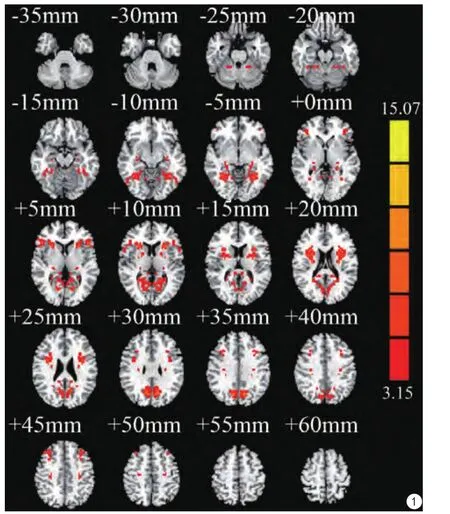

图1 VMHC结果的显著差异(红色)。使用F检验,并且使用AlphaSim校正(体素水平P<0.05,簇大小>228 mm3)将阈值设置为P<0.05。异常脑区包括楔前叶、矩状回、梭状回、楔叶、舌回、颞下回、海马、额中回、额下回Fig. 1 Significant difference in the VMHC results (red). The F-test was used, and the threshold was set to P<0.05 with AlphaSim correction(individual P<0.05, cluster size>228 mm3). The aberrant regions included the precuneus, calcarine, fusiform, cuneus, lingual gyrus, temporal inferior gyrus, hippocampus, frontal middle gyrus, frontal inferior.

2 结果

2.1 临床资料

最终入组的被试包括:30个AD、14个aMCI和18个HC。所有研究对象的临床资料见表1。三组在性别、年龄、受教育程度方面无显著统计学差异(P>0.05);MMSE和MoCA评分在各组之间有显著差异(P<0.05)。

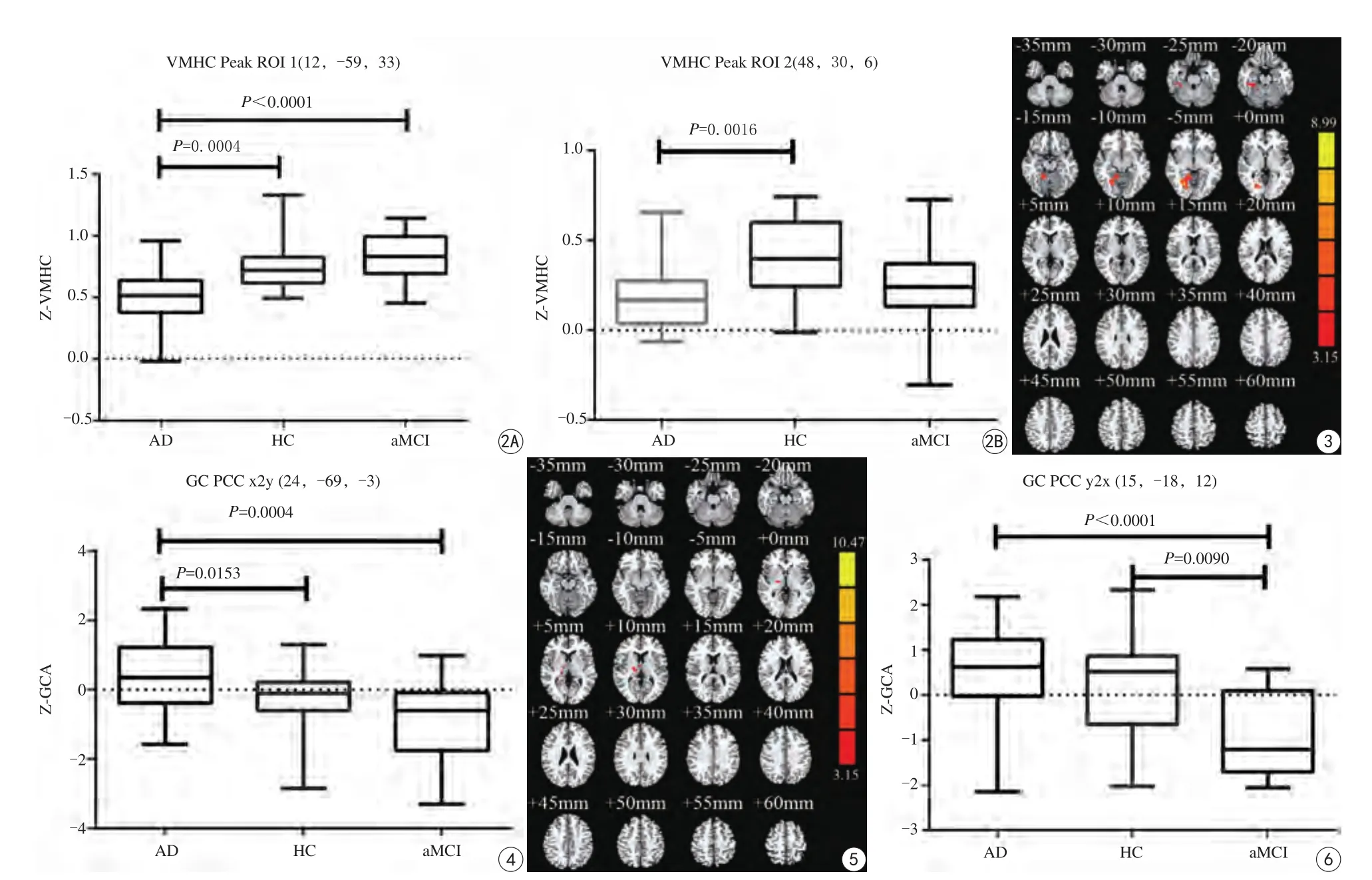

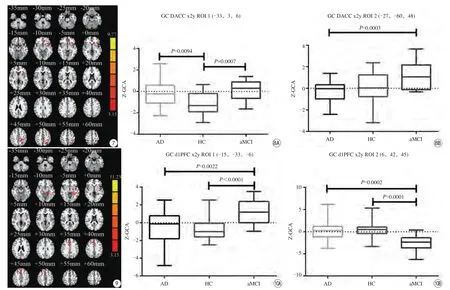

图2 VMHC/GCA分析结果。A:从ROI 1 (右侧楔前叶,位于x=12,y=-69,z=33)中提取的VMHV值在AD/aMCI/HC组之间的成对比较;B:从ROI 2 (右侧额中回,位于x=48、y=30、z=6)中提取的VMHV值在AD/aMCI/HC组之间的成对比较 图3 GCA结果的显著差异(从PCC到全脑的有向功能连接,x2y,红色),使用F检验,并且使用AlphaSim校正(体素水平P<0.05,簇大小>228 mm3)将阈值设置为P<0.05。异常脑区包括舌回、梭状回、小脑4、5区和右侧海马旁回 图4 VMHC/GCA分析结果。从PCC到其他区域(x2y),从ROI(右侧舌回,位于x=24,y=-69,z=-3)中提取的显著GC值在AD/aMCI/HC组之间的成对比较 图5 GCA结果的显著差异(从其他脑区到PCC的有向功能连接,y2x ,红色),使用F检验,并且使用AlphaSim校正(个体P<0.05,簇大小>228 mm3)将阈值设置为P<0.05。异常脑区是右侧丘脑 图6 VMHC/GCA分析结果。从其他区域到PCC (y2x),从ROI(右侧丘脑,位于x=15,y=-18,z=12)中提取的显著GC值在AD/aMCI/HC组之间的成对比较Fig. 2 VMHC/GC analysis results. A: Pair-wise comparisons for the VMHC value extracted from ROI 1 which was the right precuneus (centering at x=12,y=-69, z=33) between the AD/aMCI/HC groups. B: Pair-wise comparisons of variance for the VMHC value extracted from ROI 2, which was the right frontal middle gyrus (centering at x=48, y=30, z=6) between the AD/aMCI/HC groups. Fig. 3 Significant differences in the GCA results(directed connectivity from the PCC to the whole brain, x2y, red). The F-test was used, and the threshold was set to P<0.05 with AlphaSim correction (individual P<0.05, cluster size>228 mm3). The aberrant regions included the lingual gyrus, fusiform gyrus, cerebelum 4, 5 and right parahippocampal gyrus. Fig. 4 VMHC/GC analysis results. Pair-wise comparisons for the significantly different GC values extracted from the ROI, which was the right lingual gyrus (centering at x=24, y=-69, z=-3) from the PCC to other regions (x2y) between the AD/aMCI/HC groups. Fig. 5 Significant differences in the GCA results (directed connectivity from other regions to PCC, y2x, red). The F-test was used, and the threshold was set to P<0.05 with AlphaSim correction (individual P<0.05, cluster size>228 mm3).The aberrant region was the right thalamus. Fig. 6 VMHC/GC analysis results. Pair-wise comparisons for the significantly different GC values extracted from the ROI, which was the right thalamus (centering at x=15, y=-18, z=12) from other regions to the PCC (y2x) between the AD/aMCI/HC groups.

2.2 VMHC 分析结果

图1显示了具有VMHC结果的三组中显著不同的脑区,显示了初级视觉皮层和高级视觉皮层、梭状回、默认网络脑区(即楔前叶、海马)和ECN相关脑区(即额中回)。从两个ROI (ROI 1在右侧楔前叶(峰值Z-VMHC位于x=12,y=-69,z=33),ROI 2在右侧额中回(峰值Z-VMHC位于x=48,y=30,z=60)中提取VMHC值,与HC和aMCI组相比,AD组显著降低(图2A、B),而在HC和aMCI组之间没有观察到显著差异。

2.3 GCA分析结果

2.3.1 从PCC到其他脑区

图3显示了从PCC种子点到其他脑区的有向功能连接,三组之间的GC值有显著差异。有差异的脑区集中在DMN内的舌回、梭状回、小脑4、5区和右侧海马旁回。从右侧舌回提取ROI(峰值Z-GC位于x=24,y=-69,z=-3)(图3)。三组比较显示,AD组的GC值高于其他两组,表现出兴奋性连接(GC值增加)。相比之下,aMCI组显示抑制性连接(GC值显著低于AD组)(图4)。

图7 GCA结果显著差异(从dACC到全脑的有向功能连接,x2y,红色)。使用F检验,并且使用AlphaSim校正(个体P<0.05,簇大小>228 mm3)将阈值设置为P<0.05。异常脑区包括左侧脑岛、壳核、尾状核、额中回、顶上/下小叶和中央后回 图8 SN/ECN的GCA结果。A:AD/aMCI/HC组之间ROI 1 (左侧脑岛,位于x=-33,y=3,z=6)中从dACC到其他脑区的GC值的成对比较;B:AD/aMCI/HC组之间ROI 2 (左侧顶叶,位于x=-27,y=-60,z=48)中从SN到ECN的GC值的成对比较 图9 GCA结果显著差异(从dlPFC到全脑的有向功能连接,x2y ,红色)。使用F检验,将阈值设置为P<0.01 (无校正,簇大小>40 mm3)。异常区包括左侧海马旁回、海马、豆状核、颞中回、舌回、苍白球、双侧内侧额上回、额上回和辅助运动区 图10 SN/ECN的GCA结果。A:AD/aMCI/HC组之间ROI 1(左侧海马旁回,位于x=-15,y=-33,z=-6)中从ECN 到DMN的GC值的成对比较;B:AD/aMCI/HC组之间ROI 2 (左侧内侧上额回,位于x=6,y=42,z=45)中从ECN 到SN的GC值的成对比较Fig. 7 Significant differences in the GCA results(directed connectivity from the dACC to the whole brain, x2y, red). The F-test was used, and the threshold was set to P<0.05 with AlphaSim correction (individual P<0.05, cluster size>228 mm3). The aberrant regions included the left insula, putamen, caudate,frontal middle orb gyrus, parietal superior/inferior gyrus and postcentral gyrus. Fig. 8 GCA results of SN/ECN. A: Pair-wise comparisons for the significantly different GC values extracted from ROI 1, which was the left insula (centering at x=-33, y=3, z=6) from the dACC to other regions within the SN between the AD/aMCI/HC groups. B: Pair-wise comparisons for the significantly different GC values extracted from ROI 2, which was the left parietal (centering at x=-27, y=-60, z=48) from the SN to the ECN between the AD/aMCI/HC groups. Fig. 9 Significant differences in the GCA results (directed connectivity from the dlPFC to the whole brain, x2y, red). The F-test was used, and the threshold was set to P<0.01 (uncorrected, cluster size>40 mm3). The aberrant regions included the left parahippocampal gyrus, hippocampus, lentiform nucleus, temporal middle gyrus, lingual gyrus, pallidum, bilateral superior medial frontal gyrus, superior frontal gyrus and supplementary motor area. Fig. 10 GCA results of SN/ECN. A: Pair-wise comparisons for the significantly different GC values extracted from ROI 1, which was the left parahippocampal gyrus (centering at x=-15, y=-33, z=-6) from the ECN to the DMN between the AD/aMCI/HC groups. B: Pair-wise comparisons for the significantly different GC values extracted from ROI 2, which was the left superior medial frontal gyrus (centering at x=6, y=42, z=45) from the ECN to the SN between the AD/aMCI/HC groups.

2.3.2 从其他脑区到PCC

从其他脑区到PCC种子点的GC值在三组之间不同。这种差异主要出现在DMN内的右侧丘脑中,峰值Z-GC位于x=15,y=-18,z=12(图5)。aMCI组与其他两组相比差异有统计学意义;然而,AD和HC组之间没有显著性差异。组间比较发现AD组和HC组显示兴奋性连接,而aMCI组显示抑制性连接(图6)。

2.3.3 从SN到其他脑区

笔者观察到SN中异常的有向功能连接,其中dACC是SN的代表性种子点。在SN内纹状体(包括尾状核和壳核)中观察到这种异常的活性(图7)。从左侧脑岛提取ROI 1(峰值Z-GC位于x=-33,y=3,z=6)。SN中的有向功能连接显示aMCI组的兴奋性特征,与HC组的抑制性连接相比有显著差异。AD组的GC值显示较HC组更高的抑制性连接(图8A)。此外,显示明显差异的ROI 2源于ECN中的左顶叶(峰值Z-GC位于x=-27,y=-60,z=48)。该结果提示从SN到ECN有向功能连接的显著差异。这种SN-ECN连接在aMCI组中显示为明显增加的兴奋性连接,并且与其他两组相比显示出显著差异(图8B)。

从其他脑区到dACC的连接性在三组之间没有观察到显著差异。

2.3.4 从ECN到其他脑区

在以dlPFC为代表性种子点的ECN与全脑网络的有向功能连接中检测到差异。从ECN到DMN的异常有向功能连接包括左侧海马旁回、海马、豆状核、颞中回、舌回和苍白球,从左侧海马旁回提取峰值Z-GC (x=-15,y=-33,z=-6)。从ECN到SN的异常有向功能连接包括两侧额上回内侧、额上回和辅助运动区,从额上回内侧取峰值Z-GC(x=6,y=42,z=45)(图9)。ECN-DMN连接在aMCI组中是兴奋的,但在AD和HC组中是抑制的。aMCI和其他两组之间存在显著差异(图10A)。在三组中均观察到ECN-SN连接的变化。AD和HC组显示显著的兴奋性连接,而aMCI组显示显著的抑制性连接(图10B)。

从其他脑区到dlPFC的连接性在三组之间没有观察到显著差异。

3 讨论

3.1 AD及aMCI患者“三网络”VMHC和GCA异常改变的意义

Menon[5]提出在三个核心脑网络(即DMN、SN和ECN)之间和各自网络内部的相互作用失调可能是神经精神障碍的发病基础。最近的一项研究表明,功能连接的改变早于灰质结构的改变,对预测MCI提供了重要手段[15]。在大多数关于AD及aMCI的rs-fMRI 研究中,DMN最受关注[16-18],然而对三个脑网络内部及之间定向连接的研究非常少。本研究涉及另外一个重要问题,就是无向连接与有向功能连接谁更敏感?“三网络模型”的特点是楔前叶、海马、颞叶、额中回和其他脑区的对称性无向连接的变化。在本研究中这种变化主要表现为AD组功能连接减少,并且aMCI和HC组之间显示没有显著差异,提示VMHC不能识别aMCI 较HC更细微的病理变化。相比之下,GCA能够显示aMCI、AD和HC组之间的显著差异。因此,笔者认为有向功能连接比脑网络内的无向连接更加敏感。

3.2 DMN的功能连接改变及其意义

DMN在认知过程期间执行抑制性激活,当脑网络中存在病理变化时,观察到激活的增加。DMN的核心脑区主要包括大脑前部内侧前额叶皮层(MPFC)、PCC、下顶叶皮层(IPC)、下颞叶皮层(ITC)和海马结构。在大多数rs-fMRI研究中,DMN最受关注,因为可以在AD、MCI以及高风险AD受试者中观察到其功能连接的改变[19-20]。大多数基于种子点和独立成分分析(independent component analysis,ICA)的研究表明,在AD和MCI患者中DMN和其他脑网络功能连接减少。然而,在DMN中,MCI与AD患者的功能异常模式是不同的。在MCI患者中,DMN内不同脑区之间的功能连接有报道缺失或减低[21]。一项采用种子点的方法发现,MCI患者在内侧前额叶区域和PCC之间,PCC、海马旁回与前部海马之间DMN连接增加[22]。Damoiseaux等[17]的ICA研究显示AD 患者早期后部DMN功能连接开始减少,而前部和腹部DMN的连接则增强,随着疾病的进展所有网络连接均减少。在本研究中,DMN内的有向功能连接和从DMN到视觉皮层(即舌回和梭状回)的有向功能连接在三组中是不同的。AD组显示兴奋性连接,相反,aMCI和HC组的连接显著降低。aMCI的GC值最低,其可能反映了代偿性连接。此外,从DMN到舌回和梭状回的功能连接改变可能是AD患者记忆障碍的主要原因,并反映视觉相关皮层网络异常[12]。从DMN到其他脑区的有向功能连接显示小脑4、5区是三组间有显著差异的脑区之一,提示小脑局部功能连接的变化可能是AD的发病机制之一。

3.3 SN的功能连接改变及其意义

SN可以引导DMN和ECN执行认知任务并帮助目标脑区对刺激做出适当反应,在认知任务表现中起关键作用。有趣的是,SN可通过其关键区域(前脑岛和背侧前扣带回)中独特的细胞结构来促进其控制功能[23]。SN通常在刺激驱动的认知处理期间显示兴奋性。Zhou等[24]报道AD患者的SN内功能连接增加。然而,He等[25]发现在MCI和AD患者中,SN内的结构和功能都存在损伤。Chand等[26]指出在MCI中SN的调制模式被破坏,此外,SN控制的破坏程度与总体认知表现下降显著相关。本研究结果表明在aMCI中出现以dACC为代表性种子点的SN内兴奋性有向功能连接。笔者推测因为在aMCI阶段,焦虑和抑郁是突出的伴随症状,并且可以增加SN的兴奋性连接,另一个可能的原因就是代偿机制。相比之下,AD组显示抑制性连接减弱,可能因为SN负责高级认知功能,如社会和情感信息,并在其刺激驱动时激活增加。

3.4 ECN的功能连接改变及其意义

ECN在情感信息处理期间显示兴奋性连接,与在SN中观察到的类似。Sorg等[27]观察到在aMCI患者中,DMN和ECN中功能连接减少。Balachandar等[28]则发现轻度AD病人的DMN内功能连接减少,而ECN内功能连接增加。在本研究中,ECN到DMN的有向功能连接,以dlPFC为代表性种子点,在多个脑区(包括海马/海马旁回、豆状核、颞中回)中检测到差异。aMCI组的兴奋性连接可能代表另一种类型的代偿性保护。除了DMN中双向的有向功能连接,笔者并没有观察到SN和ECN中异常的反向连接,可能因为DMN是AD及aMCI中最重要的相关网络。

本研究具有一定的局限性。由于样本量相对较小,统计分析可能会有一定的偏倚。虽然三组在性别比分析上没有显著的统计学差异,但是研究并没有做到完全的1:1匹配,所以不能完全排除其对研究结果的影响。

综上所述,通过VMHC与GCA技术对三个核心脑网络的分析,笔者认为有向功能连接比无向半球间连接更加敏感。这些研究结果表明在三个核心脑网络中观察到的变化可以作为aMCI患者的神经影像学指标,用于区分AD、aMCI患者及HC。

参考文献 [References]

[1]Morris JC, Storandt M, Miller JP, et al. Mild cognitive impairment represents early-stage Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol, 2001, 58(3):397-405.

[2]Zhao Q, Li W, Nedelska Z, et al. Spatial navigation impairment is associated with alterations in subcortical intrinsic activity in mild cognitive impairment: a resting-state fmri study. Behav Neurol, 2017,2017: 1-9.

[3]Ren P, Heffner KL, Jacobs A, et al. Acute affective reactivity and quality of life in older adults with amnestic mild cognitive impairment: a functional MRI study. Am J Geriat Psychiat, 2017,25(11): 1225-1233.

[4]Wang P, Li R, Yu J, et al. Frequency-dependent brain regional homogeneity alterations in patients with mild cognitive impairment during working memory state relative to resting state. Front Aging Neurosci, 2016, 24, 8: 60.

[5]Menon V. Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model. Trends Cogn Sci, 2011, 15(10):483-506.

[6]Zang ZX, Yan CG, Dong ZY, et al. Granger causality analysis implementation on MATLAB: a graphic user interface toolkit for fMRI data processing. J Neurosci Meth, 2012, 203(2): 418-426.

[7]Miao X, Wu X, Li R, et al. Altered connectivity pattern of hubs in default-mode network with Alzheimer's disease: an Granger causality modeling approach. Plos One, 2011, 6(10): e25546.

[8]Stark DE, Margulies DS, Shehzad Z, et al. Regional variation in interhemispheric coordination of intrinsic hemodynamic fluctuations.J Neurosci, 2008, 28(51): 13754-13764.

[9]McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement,2011, 7(3): 263-269.

[10]Rivasvazquez RA, Mendez C, Rey GJ, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: new neuropsychological and pharmacological target.Arch Clin Neuropsych, 2004, 19(1): 11-27.

[11]Kelly C, Zuo XN, Gotimer K, et al. Reduced interhemispheric resting state functional connectivity in cocaine addiction. Biol psychiat,2011, 69(7): 684-692.

[12]Yu E, Liao Z, Mao D, et al. Directed functional connectivity of posterior cingulate cortex and whole brain in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Curr Alzheimer Res, 2017, 14(6):628-635.

[13]Hedden T. Disruption of functional connectivity in clinically normal older adults harboring amyloid burden. J Neurosci, 2009, 6(4):12686-12694.

[14]Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control.J Neurosci, 2007, 27(9):2349-2356.

[15]Gili T, Cercignani M, Serra L, et al. Regional brain atrophy and functional disconnection across Alzheimer's disease evolution. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2011, 82(1): 58-66.

[16]Wang Z, Liang P, Jia X, et al. The Baseline and longitudinal changes of pcc connectivity in mild cognitive impairment: a combined structure and resting-state fMRI study. Plos One, 2012, 7(5): e36838.

[17]Damoiseaux JS, Prater KE, Miller BL, et al. Functional connectivity tracks clinical deterioration in Alzheimer's disease. Neutobiol Aging,2012, 33(4): 828.

[18]Li M, Zheng G, Zheng Y, et al. Alterations in resting-state functional connectivity of the default mode network in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: an fMRI study. Bmc Med Imaging, 2017, 17(1): 48.

[19]Spreng RN, Mar RA, Kim AS. The common neural basis of autobiographical memory, prospection, navigation, theory of mind,and the default mode: a quantitative meta-analysis. MIT Press J,2009: 489-510 .

[20]Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Moran JM, Nieto-Castañón A, et al.Associations and dissociations between default and self-reference networks in the human brain. Neuroimage, 2011, 55(1): 225-232.

[21]Sorg C, Riedl V, Mühlau M, et al. Selective changes of resting-state networks in individuals at risk for Alzheimer's disease. P Natl Acad Sci Usa, 2007, 104(47): 18760-18765.

[22]Gardini S, Venneri A, Sambataro F, et al. Increased functional connectivity in the default mode network in mild cognitive impairment: a maladaptive compensatory mechanism associated with poor semantic memory performance. J Alzheimers Dis, 2015, 45(2):457-470.

[23]Bonnelle V, Ham TE, Leech R, et al. Salience network integrity predicts default mode network function after traumatic brain injury. P Natl Acad Sci Usa, 2012, 109(12): 4690.

[24]Zhou J, Greicius MD, Gennatas ED, et al. Divergent network connectivity changes in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain, 2010, 133(Pt 5): 1352-1367.

[25]He X, Qin W, Liu Y, et al. Abnormal salience network in normal aging and in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Hum Brain Mapp, 2014, 35(7): 3446-3464.

[26]Chand G, Wu J, Hajjar I, et al. Interactions of the salience network and its subsystems with the default-mode and the central-executive networks in normal aging and mild cognitive impairment. Brain Connectivity, 2017., 7(7): 401-412.

[27]Sorg C, Riedl V, Mühlau M, et al. Selective changes of resting-state networks in individuals at risk for Alzheimer's disease. P Natl Acad Sci Usa, 2007, 104(47): 18760-18765.

[28]Balachandar R, John JP, Saini J, et al. A study of structural and functional connectivity in early Alzheimer's disease using rest fMRI and diffusion tensor imaging. Int J Geriatr Psych, 2015, 30(5): 497-504.