作为公共空间的交通枢纽

张利/ZHANG Li

当代生活的一个重要部分是移动性。以任何现在的都市居民而言,日常生活的时间有很大比例是在公共交通空间里度过的。哪种形式的公共交通是最好的公共交通?对此每个都会有不同的答案。不过21世纪的城市设计家们似乎在这个问题达成了一定程度的共识:由轨道(重轨或轻轨)连接的超级密度组团是最值得提倡,也是最具可持续性的[1]。类似的,在当今的城市更新项目中,不管是在发达国家的城市还是发展中国家的新兴城市,与轨道交通相关的基础设施更新也是颇受关注的热点。我们经常体会到的现象是,无论对于城市的居民还是对于城市的造访者来说,轨道交通空间已经成为了事实上的城市识别性的缔造者之一。轨道交通(换乘)枢纽中的声音、气味、触感与背景氛围共同交织成了一种难以忘怀的经历,以不可忽视的方式参与了我们生活品质的定义。

轨道交通(换乘)枢纽是城市化的产物,其出现可追溯到工业化的初期。然而就像现代城市本身经历了很长的历程才认识要把人放回到一切考虑的中心一样,交通枢纽在接受自己是普通人的城市公共空间这一角色定位之前,也经历了漫长的技术至上与形像崇拜过程。过剩的石头与铸铁的纪念性曾一度是帝国式的经济进步的标志。超尺度的屋盖与巨型的内部空间让交通枢纽更像是宫殿而不是站房。令人颇感意外的是,这一源自欧洲帝国主义时代的交通建筑纪念性传统在历史上竟获得了比产生它的那些帝国更长的生命力。从传统的城市到新兴的城市,对交通枢纽纪念性形像的追求似乎令人欲罢不能。在20世纪的莫斯科我们看到宫殿式、博物馆式的地铁站的繁盛。在21世纪我国的新城我们看到高铁站构筑的宏伟。在最近的纽约,我们再次见到了以夸张的技术表现枢纽形像的高显现度案例——只不过其实现的材料是透明玻璃和白色金属,而不是石头与铸铁罢了。

具有讽刺意味的是,作为公共空间的交通枢纽出现于一个与之并不相容的政治气候中。20世纪第二个10年,以在西方各国影响加剧的经济危机为背景,莫索里尼政权的主要政策定型并开始主导主要意大利城市的进程。在随后的一段时间中,作为刺激经济的主要手段,各大城市纷纷在中心区域进行以公有资金支持的大型交通基础设施建设。1933年佛罗伦萨的主火车站竞赛把以米凯卢奇为首的年轻建筑师团队推向了前台,他们设计方案所承载的“对新建筑的宣扬直接引发了一场在(政治允许的)界限内的争论,而这一争论针对的是(对公共交通空间属性的)立场与独特解决方法”[2]。这一“争论”的焦点或“独特解决方法”所指的正是与城市标高取平的大通廊空间(不再被有意架高)集成大量的日常城市服务功能。当然,佛罗伦萨主火车站当年的城市性空间与今天的同类空间在尺度上与丰富程度上都不可同日而语,但它确实是一个典型的早期案例,不仅对火车站、也对所有城市公共交通枢纽给予了一种新的定义,在这种定义下,强功能性的车站与泛功能性的城市公共空间之间的界限开始被跨越。

80余年以后的今天,我们几乎可以安心地说,交通枢纽已越来越多地被默认是城市公共空间的重要类型。虽然反例还是屡见不鲜,但绝大多数的交通枢纽对待人性化体验的态度是严肃的。我们可以通过4个特性来识别这一交通枢纽向人性化公共空间转型的进程。

第一个特性是给予慢行交通以空间主导权,设计大面积的连续延展表面以供行人与自行车使用。多数现代交通枢纽或换乘中心会有意弱化传统车站的通廊与候车室构架,而用室内的公共广场和街道来对其进行替代。无论在新建交通枢纽还是老旧车站的改造中,这一属性都有着相当明显的表达。苏黎世中心车站的改造索性把老站房的内部全部清空,形成一个完整的室内公共空间,类似一个传统的城市中心市场。这种类型学的功能柔性与空间活力可谓是任何21世纪国际都市的主要加分项目之一。

第二个特性是在交通枢纽空间内集成丰富的休闲与公共服务功能。不仅是零售、咖啡、餐厅等传统的交通辅助功能,还包括画廊、游戏厅、展览厅甚至电影厅和图书馆等文化休闲功能。这在近期新一轮的欧洲城市火车站建设中非常普遍。代尔夫特新的中心火车站显然没有忘记其城市的塑造者——代尔夫特技术大学的存在,因而在火车站的水平向大厅中设置了多个新能源技术汽车的展台,把大厅变成了展厅。现代的交通枢纽看来对于这种新的公共空间角色是越来越自信了,它们有理由相信,即使是最行色匆匆的过客,也会因空间设计质量与内容的提升而在交通枢纽内多停留一段时间,而正是这种剩余停留时间人次的积累,使得交通枢纽作为公共空间的成色越来越足。

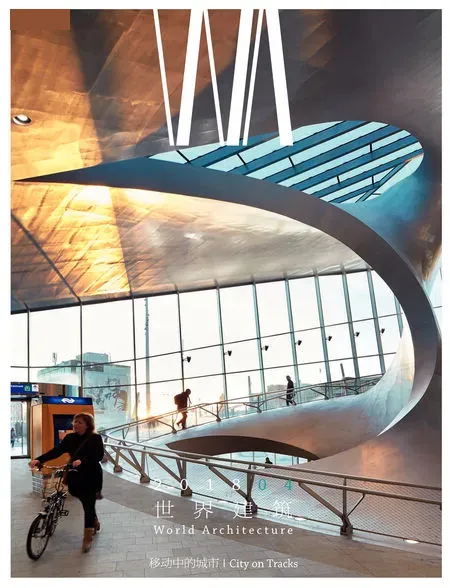

第三个特性是把交通枢纽的空间当成是一种都市景观进行设计,全然颠覆掉纪念性交通空间的传统。在纪念性主导的时代,交通枢纽的设计是关于屋顶、柱子、墙体和立面的,而在都市景观的时代,交通枢纽的设计只有一个优于任何其他表面的关注——我们行走移动的水平面——地面。在阿纳姆中心换乘枢纽的设计中,这一关注造就了一个令人兴奋的延展与缠绕地面体系,其所能承载的移动与活动类型超乎最初的想像。这可能是源于荷兰人挥之不去的自行车情结,也可能是源于建筑师对流动延伸空间的钟情,无论如何,它给予过客以一种类似公园般惬意的移动体验——在车站里消磨时间,如同在公园里一般?这听起来真是不坏。

第四个特性要复杂得多,虽然在视觉上它最容易识别,即使在进入枢纽空间前。这个特性就是时下盛行的直接以交通枢纽为基底,在其上进行综合开发,即TOD,或交通综合开发。根据不少专业人士的解释,直接在交通枢纽上进行综合开发,集结高密度的空间,堆迭复杂的多种功能(包括工作和居住),以及采用垂直发展的类型是最大化利用交通枢纽便利性的灵丹妙药。东京周边的高密度区域是这一模式的先行者(多数为东京铁路公司自行开发),而其显而易见的固定资产市场吸引力则直接在柏林或深圳的同类建设中得到了发挥。一方面,我们必须承认在最小的城市足迹上建设紧凑的、超高密度的微型城市是一种非常进步的实验,另一方面,我们也需要认知它的风险。这里的一个重要问题是在某地进行TOD开发的缘起究竟是什么。如果是增长的局域人口的刚性需求,那么这一开发匆庸质疑将是对城市有益的。但如果是仅仅为了获得最大的市场价值,那么在相应的开发中,轨道交通的进步与革新被过度开发的贪婪所淹没也不是不可能的。□

参考文献/References

[1] Chakrabarti, Vishaan. A Country of Cities: A Manifesto for an Urban America. Metropolis Books,2013:14-25.

[2] Tafuri, Manfredo and Dal Co, Francesco. Modern Architecture/2. Electa/Rizzoli, 1976[1986]:258.

Mobility forms a quintessential part of contemporary life. For any modern metropolitan inhabitant, a significant chunk of daily life is spent on some form of public transportation. Everyone may have a different idea on which form of public transportation works the best. But the consensus of twenty-first century urbanists seems to be that the model of hyperdensity connected by rails/light rails is the most desirable and sustainable[1]. It is also common to see the updating of railway and subway infrastructure being the most popular subject of urban renewal projects, both in developed cities and emerging ones. For visitors and inhabitants alike,more often than not, the railway/subway spaces are becoming the de-facto prime identity-giver to metropolises around the world. The sound, smell,touch and vibe of major rail/light rail transit hubs have therefore become definitive experiences and qualities of our urban lives.

Transit hubs are products of urbanisation back to industrialisation times. Just as cities took a long road to eventually put humans in the centre,transit hubs had been for long a realm of technology and efficiency before finally turning into public spaces. 19th Century railway stations were objects of imperial competitions, with excessive pursuit of stone and cast-iron monumentality. Behemoth canopies and gargantuan spaces made the stations more palaces than hubs. Surprisingly, this tradition of monumentality in transit spaces has survived much longer than the imperial states that created them and have extended all the way up to our time. From old world cities to new progressive municipalities,the adoption of monumental transit hubs seemed to be irresistible. In 20th century Moscow, we saw the extravagance of metro stations as underground palaces. In 21st century emerging Chinese cities,we see the grandeur of hi-speed railway stations. In today's New York, we witness yet another manifesto of monumentality in public transportation, albeit in crystal-clear glass and clean white cladding of aluminium alloy, not stone or cast-iron.

Ironically, the making of transportation hubs as public spaces was initiated in a very unlikely political climate. In the 1920s, Mussolini's policies were fixed and started to dominant Italian urban life. In the years that followed, state sponsored projects, mostly in public infrastructure, became the main measure of stimulation to counter economical volatilities. This nevertheless led to major transformation of old urban centres. In the 1933 competition winning, rationalist project for Florence railroad station, the then young architect team led by Michelucci delivered "the advocates of a new architecture promoted a debate that remained well within the limits of discussions as to specific approaches and ways of working"[2]. And the basic quality of this "debate" and "specific approaches"was the integration of the concourse space, no longer elevated from the urban ground, with typical urban services. Though not as big as many of its counterparts today, this did give a new definition to railroad stations (and to all transportation hubs as well), in which the boundary between a station and a public space is crossed-over.

More than eight decades later, we feel reassured to say that currently, transportation hubs are moreand-more taken by default as public spaces. Although there are a few exceptions, most urban transit centres are taking the experience of the people truly seriously. The humanisation of transportation hubs can be identified through four characteristics.

The first the priority given to slow mobility,with expanded surface area serving pedestrians and bicycles. Typologically, most modern stations and transit centres would deliberately weaken the sense of concourses and lounges, while replacing them with indoor plazas, atriums and streets. This strategy is visible in both new stations and renovated old stations, In the central station of Zurich, the entire old station building is emptied to give room to an indoor public open space, not much different from a conventional city market. The fl exibility and vitality of such a typology can only be a plus to the identity of a 21st century international city.

The second is the inclusion of more recreational and public programs. The inclusion of retails, cafes and restaurant is quite conventional. But the inclusion of galleries, gaming parlours, theatres and libraries is rather intriguing, and is more and more common in European stations. The new central station in Delft, definitely inspired by the renown technological university that resides in the town, accommodates serious displays of cutting-edge renewable energy cars. It does seem that modern transportation hubs are getting more and more confident that passengerson-the-move will spend more time inside the station than their normal transit activity requires, and it is exactly this bold assumption and the related designs that makes passengers staying longer in the station,making it a truer public space.

The third is to design the spaces as urban landscapes, overhauling the traditional monumentality idea of stations/transportation hubs. While monumentality would put emphasis on roofs, columns and walls (facades), urban landscape,instead, would pay primary attention to the surface below our feet. In Arnhem Central Transfer Terminal, this attention has resulted in an amazing network of paths and surfaces intertwining more activities than what is imaginable. Partly driven by the Dutch obsession with bicycles, partly driven by the architects' obsession with flux space, this terminal does give a public park-like experience to all its visitors. More time spent in a station equals to more time spent in a park? Not a bad idea at all.

The fourth is a more complicated one, albeit visually rather distinctive. It is the tendency of developing the station or transit centre itself into a mixed-use complex, under the jargon TOD (Transportation Oriented Development).Accommodating higher density, stacking more program (including working and residential),going vertical is said to be the panacea to take full advantage of the easiest mobility access these transportation hubs provided. Pioneered by developments in ultra-dense areas near Tokyo(mostly by railroad companies themselves), this economically attractive option has seen its offspring in cities like Berlin and Shenzhen. While creating a compact, miniaturised, full-f l edged mini city on an extremely small footprint is a very progressive idea,there are caveats though. The first and the foremost one being the question of what drives a TOD. If it is the increasing demand by a growing population,fine. If it is simply the market, then probably all the good about modern rails/light rails would be overshadowed by the greed of overdevelopment.□