Wheat genome editing expedited by efficient transformation techniques: Progress and perspectives

*

Institute of Crop Science,Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences,Beijing 100081,China

1.Introduction

The challenge of feeding a global population of 9 billion by the middle of this century is enormous[1].Common wheat as a staple food crop will play a major role in meeting this challenge.Wheat has lagged behind other major cereal crops in development of genetic engineering and biotechnology because of its huge genome,high number of repetitive DNA sequences,hexaploid composition,and low regeneration following genetic transformation[2].No transgenic wheat has been commercialized and new wheat varieties are mainly developed by conventional breeding techniques that are costly and time-consuming[3].The key reasons for this is lack of a high quality reference genome sequence and difficulty in transforming wheat.

Plant transformation with exotic genes using vectors like Agrobacterium has been the first step in introducing genes of interest to plant cells that must be regenerated into plants that produce normal seeds.Common wheat as a hexaploid plant is one of the most difficult crops to be transformed.Recently,a new technique called Pure Wheat that significantly improves transformation efficiency was invented by the Japan Tobacco Company[4].This technique brings the hope of genetically manipulating wheat in a more efficient and diverse manner.It also enables application of new genome editing technologies that are applicable to wheat.

Genome editing as a recently developed technology enables precise manipulation of specific genomic sequences,and will possibly supersede traditional random mutagenesis methods in plant breeding. In general genome editing technologies involve three types of sequence-specific nucleases(SSNs),namely zinc-finger nucleases(ZFNs),transcription activator-like effector nucleases(TALENs),and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat-associated endonucleases(CRISPR/Cas).Such technologies have versatile functions including targeted gene knock-out and knock-in,gene replacement and activation,and DNA repair[5–8],and will be widely applied in crop breeding.This is likely to be led by the application of CRISPR/Cas9 with the help of plant regeneration-related genes such as Baby boom(Bbm)and Wuschel(Wus2)in co-transformation[9].

In this review,we provide a brief summary of current transformation techniques and recent breakthroughs in genetic engineering of wheat.We then review recent progress in plant genome editing and its application in wheat.Finally,we speculate future trends in wheat genetic engineering with the availability of a high quality genome sequence, a significantly improved transformation protocol,and a tool for genome editing in generating elite wheat varieties that will contribute to achievement of world food security.

2.Wheat transformation-possible after much effort

2.1.Transformation of wheat by biolistic particles

The first transgenic wheat plants were obtained by biolistic particle bombardment in 1992[10].The Bar gene as a selective marker was successfully transferred to wheat by high velocity microprojectile bombardment.This was the beginning of the era of wheat transformation.A number of genes were transformed into wheat using this approach(Table1),including functional genes such as TaPIMP1[20],Yr10[22],TcLr19PR1[23],TaNAC2[26],and TaCPK[27].Genetically enhanced wheat lines that have better resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses are still being tested.However,use of biolistic particles is notorious for its low transformation efficiency.

2.2.Wheat transformation by Agrobacterium

Agrobacterium species used for wheat transformation include A.tumefaciens and A.rhizogenes.They use a transfer DNA(T-DNA)that naturally integrates into plant genomes after infection.Agrobacterium mediated transformation has specific advantages compared to biolistic particles,including low copy number integration,a more economic and simpler procedure,and clear integration of sequences without the vector backbone.Although it is widely used by wheat scientists(Table 2),the efficiency of Agrobacterium mediated wheat transformation using immature embryos remained extremely low until recently,when the PureWheat technique was developed by the Japan Tobacco Company.This revolutionary technique involved cultivar Fielder as a host with various modifications in transformation protocols.The efficiency of this method has reached as high as 50%[4].The technique was confirmed in Australia using wheat cultivars Westonia and Gladius[40].With additional modifications the present authors'laboratory has transformed more than 15 Chinese genotypes,including elite varieties Jimai 22,Shiluan 02-1,Yangmai 16,Jimai 5265,Zhoumai 18,and Lunxuan 987,with high Agrobacterium infection efficiency and less genotype dependence(Fig.1)[39].

From our experience and that of others,a number of factors need to be considered in order to achieve high transformation efficiency.Firstly,the infection efficiency should be high.Wheat genotypes differ in susceptibility to Agrobacterium infection.Secondly,the wheat genotype should have high regeneration ability,as exemplified by Bobwhite,Fielder,Kenong 199,and Yangmai 158[4,26,31,41].Thirdly,the plants from which immature embryos are collected should bein good growth status.High temperatures in particular have adverse effect on transformation success rates[42,43].Based on our experience,mild temperatures,strong light,and good cultivation management are beneficial for high transformation efficiency[39].Transformation efficiency can be increased using the morphogenic regulator genes BABY BOOM(Bbm)and WUSCHEL2(Wus2)that have been successfully tested in maize[9].However,over-expression of Wus2 may lead to callus necrosis as well as aberrant callus phenotypes.The morphogenic regulator genes have to be excised during regeneration.

Table 1––Examples of wheat transformation achieved by biolistic particles.

3.Development of genome editing systems in wheat

3.1.The advance of plant genome editing technologies

In the past few years genome editing technologies have arisen as promising tools for crop improvement,including wheat.The earlier versions are represented by the CRISPR/Cas9 system that largely replaces the older versions such as ZFNs and TALENs due to its simplicity and economy(Table 3).The CRISPR/Cas9 system has two simple components;the Cas9 protein and the single guide RNA(sgRNA)that guides the nuclease Cas9 to target sites in a sequence-specific manner where DNA double-strand breaks(DSBs)are generated.DSBs are repaired by one of the two main competing DNA repair pathways:error-prone non-homologous end joining(NHEJ)that results in small random insertions and/or deletions(indels)at the cleavage site,or homologous recombination(HR)that leads to precise genome modification[5–8].NHEJ can be utilized to generate random changes and mutations in target sites where HR can carry out targeted knock-in,gene replacement,and DNA correction.The design of multiple sgRNAs to target multiple sequences allows multiplex high-efficiency genome engineering[44,45].These applications are extremely useful in genetic manipulation for crop improvement.

In addition to conventional functions of genome editing,such as gene insertion,gene replacement and regulation of gene expression[46–51],a catalytically inactive or ‘dead'Cas9(dCas9)that bears mutations in both the RuvC D10A and HNH H840A domains and is nonfunctional as a nuclease can be combined with proteins having other functions[52].For example,transcriptional activation or repression domains can be fused with the dCas9 to regulate endogenous gene expression[53].Additional examples are fusion of dCas9 withchromatin-modifying enzymes such as inhibitors of histone deacetylases or DNA methyltransferases to achieve altered epigenomes and transcriptomes[54–58].Other examples include light-sensitive proteins fused with dCas9 that allows rapid and reversible targeted gene activation or repression by light[59–61].

Table 2––Examples of wheat transformation mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens.

3.2.New versions of CRISPR/Cas9 systems

Since the discovery of the CRISPR/Cas9 system,a number of different versions have followed.Unlike Cas9 that is derived from Streptococcus pyogenes(SpCas9)and recognizes a relatively simple PAM(5′-NGG-3′),a new Cas9 protein from Neisseria meningitides(NmCas9)recognizes a more complex PAM(5′-NNNNGATT-3′)[62].The longer PAM reduces the accessible target range and hence potential off-target sites,leading to more precise genome editing[63].Cas9 proteins derived from other microorganisms such as Staphylococcus aureus(SaCas9)and Campylobacter jejuni(CjCas9)also have different PAMs,i.e.,5′-NNGRRT-3′and5′-NNNNRYAC-3′,respectively[64,65].CjCas9 is 984 aa in length and is the smallest Cas9 protein identified so far[65],which makes the development of expression cassettes for delivery into plant cells much easier.

Besides Cas9 proteins,other nucleases with similar genome editing functions are reported,such as Cpf1,C2c1,and C2c2 proteins[66,67].Cpf1,for example,has a RuvC-like nuclease domain,but does not have any of the HNH nuclease domains that are commonly present in Cas9.Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease lacking tracrRNA,and recognizes a T-rich PAM motif.In addition,it not only cleaves target DNA but also processes its own CRISPR RNA(crRNA)[66,68].Moreover,itgenerates staggered ends with four-or five-nucleotide overhangs,which are useful for increasing the insertion efficiency of a desired DNA fragment into the cleaved site using complementary DNA ends during HR.Application of Cpf1 might significantly enhance gene insertion efficiency at a precise genome location,a highly desirable attribute.The CRISPR-Cpf1 system has been widely tested in animals[67]as well as plants such as rice,Arabidopsis,soybean,and tobacco[69,70].

The second Cas9-likeprotein isC2c1,which isa dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease that generates a staggered break of target DNA with a six-to-eight nucleotide(nt)overhang at 5′ends.This endonuclease is reported to be highly sensitive to nucleotide mismatches to the target DNA[71].C2c2 is the latest developed technique that enables genome editing at the RNA level[72].C2c2 is an RNA-guided RNA-targeting effector.It contains two highly conserved R-X-H motifs that comprise the typical higher eukaryote and prokaryote nucleotide-binding HEPN domain,but lacks an identifiable DNase catalytic site[73].The RNA molecule in this system is cleaved outside of the base-paired region by the C2c2 complex.In addition,the C2c2 complex can also cleave other RNA molecules in trans in a sequence-nonspecific manner[74].

3.3.Single-base editing—an ultra-precise technology

Fig.1–GUS transient expression in immature embryos of various Chinese wheat varieties after five days of co-cultivation with Agrobacterium.

A recently invented single base editing approach enables a direct,irreversible conversion of a single-nucleotide base to another base in a programmable manner[75].This method does not generate DSB cleavages or require a donor template,and does not induce an excess of stochastic insertions and deletions.In principle,dCas9 is fused to a cytidine deaminase enzyme that mediates the direct conversion of cytidine to uridine,thereby leading to the change of a C/G pair to a T/A pair.Base editing would convert cytidines within a range of approximately five nucleotides.Four kinds of cytidine deaminase enzymes(human AID,human APOBEC3G,rat APOBEC1,and lamprey CDA1)were detected for base editing efficiency and rat APOBEC1 showed the highest deaminase activity in human cells[75].Target-AID (target-activation induced cytidine deaminase)comprised of dCas9 fused to Petromyzon marinus cytidine deaminase(PmCDA1)has been used to generate point mutations in tomato(Solanum lycopersicum)[76]and rice[77].

3.4.Genome editing in wheat

Chinese scientists are leading the genome editing effort in wheat.The first successful case of using the CRISPR/Cas9 system was in wheat protoplasts where mutations of wheatdisease resistance gene TaMLO were generated with a mutagenesis frequency of 28.5%[78].Later,fertile transgenic wheat plants with edited genomes were produced by the older genome editing method TALENs[79].The disruption of all three TaMLO homoeologs generated plants with resistance to powdery mildew.Soon thereafter,transgenic wheat plants carrying mutations in the TaMLO-A1 allele were generated by Cas9 technology.Moreover,the GFP,His-tag and Myc-tag genes were successfully inserted into desired loci in wheat protoplasts.A detailed CRISPR/Cas-mediated mutagenesis protocol in wheat protoplasts was recently described for target sequence selection,construction,and verification of sequence-specific sgRNAs[80].

Table 3–Comparisons of ZFNs,TALENs,and CRISPR on genome editing.

Targeted genes TaGASR7,TaGW2,and TaLOX2 in hexaploid heat and TdGASR7 in tetraploid durum wheat that are associated with grain yield or disease resistance,were successfully edited by transient expression systems of TECCDNA and TECCRNA;in particular,homozygous mutants and transgene-free plants were obtained in the T0generation[81].Moreover,by delivering CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoproteins into immature wheat embryo cells,editing of genes TaGW2 and TaGASR7 was achieved in varieties Kenong 199 and YZ814 without transgene integration[82].A dCas9 fused with cytidine deaminase enzyme enabled direct and irreversible programmed conversion of one target DNA base into another,i.e.,‘base editing'was also reported in wheat[83].In this case,the coding sequence of blue fluorescent protein(BFP)was edited to produce green fluorescent protein(GFP)by changing the 66th codon CAC(histidine)to TAC(tyrosine)without double-strand breaks or application of a foreign DNA donor.A similar single base edition,a C to T substitution,was made for the TaLOX2 gene[83].We expect the leap in wheat transformation efficiency will lead to a functional genomics research era in wheat.

4. Perspectives in developing genetically engineered wheat

4.1.Increased transformation efficiency provides a jump start for genome editing

Until recently it was difficult to imagine that wheat transformation efficiency could reach 50%in any genotype[4].The realization of highly efficient transformation and improvement in techniques that remove the obstacle of genotypic limitation provides a launching pad for functional studies and application of new technologies such as genome editing.Transformation will soon no longer be a bottleneck for genome editing in wheat.Despite this,further efforts are needed to progress genetic engineering to a level of developing elite varieties that meet world food requirements.

Overcoming genotype dependence is a revolutionary breakthrough in plant transformation.This breakthrough first came in maize.Co-overexpression of morphogenic regulator genes Bbm and Wus2 by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of immature embryos led to high transformation frequencies in several previously recalcitrant maize inbred lines[9].In addition,the combined use of Bbm and Wus2 enhanced transformation efficiency in sorghum,rice,and sugarcane.These kinds of genes can also be used in wheat to solve the bottleneck of genotype dependence in plant regeneration in further improving transformation efficiency and accelerating the application of genome editing technology.

4.2.Additional measures to further increase transformation efficiency

Most current wheat transformation protocols require immature embryos for callus production.High quality immature embryos demand well-grown plants that are mostly produced in environments that require extra inputs and costs.Use of mature embryos would remove seasonal limitations and the need to maintain high-cost conditions for plant growth.

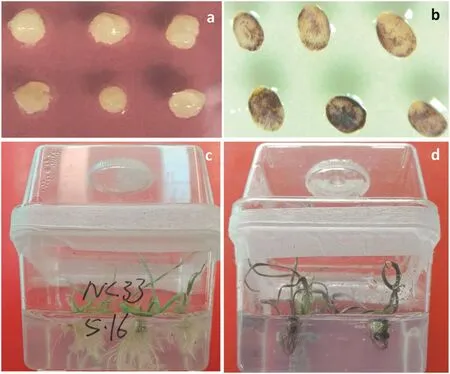

The second measure to further increase wheat transformation efficiency is to develop and use visible selection markers.This is because detection of positive transgenic wheat plants using current molecular tools and chemical markers is still time-consuming and costly.In this regard,pigment encoded genes as visible markers can be employed for direct identification of transgenic tissues or plants.In fact,transgenic rice with purple endosperm was generated by the transference of eight anthocyanin-related genes(two regulatory genes from maize and six structural genes from Coleus)[84].Purple transgenic wheat plants have also been obtained in the authors' laboratory by transferring two anthocyanin-related genes from maize(Fig.2).We can link the anthocyanin-related genes with a selective gene such as nptII,bar,or hpt,to identify transgenic wheat plants directly by color.The application of these extra measures should further increase wheat transformation efficiency to an industrial level for future commercialization.

4.3.Developmentofmarker-freeandtransgene-free engineered wheat plants

For a long time,selective markers used in transgenic plants were antibiotic resistance genes that caused a focus of public concern.Current approaches to generate marker-free transgenic plants use FLP/FRT and Cre/lox site-specific recombination,multi-auto-transformation,co-transformation,and marker-free binary vectors [85]. Among these,co-transformation is the most efficient and simple technique[86],where a co-transformed T-DNA vector that carries the selective marker can be separated from the one carrying the target gene by genetic segregation.Visible markers are an alternate way for marker-free transformation when they are linked with a selective marker.Transgenic plants with no color are marker free.The use of a visible marker linked with the genome editing cassette can accelerate detection rates for positively edited cells or plants because the presence of the color suggests expression of genome editing machinery and hence the plants have a higher possibility of being edited.

Fig.2–Primary transformation of visible markers(two anthocyanin-related genes from maize)into wheat by Agrobacterium-mediation.(a)Immature wheat embryos infected by the Agrobacterium containing a normal vector without a visible markers.(b)Expression of visible marker genes in immature wheat embryos following Agrobacterium infection.(c)Transgenic wheat plants transformed with normal vectors without visible markers.(d)Transformed wheat plants expressing a visible marker.

The presence of genome editing technology makes transgene-free genetic engineering possible.Currently,there are three promising methods to create transgene-free plants:TECCDNA,TECCRNA,and direct transfer of TALENs or Cas9 protein into cells[81,87–89].Wheat transgene-free mutant plants without herbicide selection have been obtained by these methods[81,82].However,all three methods have a low efficiency due to lack of selection during plant regeneration from tissue culture.Transformation efficiency for the model wheat genotype Fielder was>50%with selection whereas it was only 3%without selection pressure[40].The problem of low efficiency in generating transgene-free plants can be alleviated by use of visible markers,where transgenic cells can be selected by color after Agrobacterium infection,and transgene-free plants can be obtained in the following generation when the visible marker disappears.

4.4.Increasing the accuracy of wheat genome editing

Although many examples demonstrate that genome editing is a powerful tool for generating future elite crops,some problems remain.One problem is undesired off targeting due to the nature of the Cas9 enzyme to tolerate mismatches between the sgRNA and target DNA sites[44,90,91].A few strategies have been developed to improve the specificity of Cas9-mediated genome editing.One way to reduce off-targeting during genome editing is to use a pair of Cas9 nickases,i.e.,one Cas9 and one D10A,a nickase-mutated version of Cas9 that produces a single-strand break(SSB)[44,90].Two distinct sgRNAs can then be used,resulting in SSBs on each of the two DNA strands,leading to site-specific DSBs.The Cas9-D10A system has been tested in human cells and shown to reduce off-target activity by 50-to 1500-fold[92].Recent studies demonstrated that Cpf1 has much greater specificity than classical Cas9 nucleases[93].

For many existing elite varieties,genetic variation often occurs in a few bases[94].Current methods of identifying point mutations(such as targeted induced local lesions in genomes,or TILLING)are time-consuming and only detect limited numbers of point mutations[95].Thus,single-base editing could play a much larger role in this regard.The dCas9-cytidine deaminase system is very efficient,but is limited to the conversion of C/G to T/A,whereas C to G replacement occurs only at low frequency[77].Additional studies are needed to expand editing capabilities that should contribute to more efficient plant genetic engineering.

5.Conclusions

An efficient wheat transformation system has now been established,providing the required platform for developing genome editing technologies.It can be expected that more genes will be modified to increase yield and enhance stress tolerance. These technologies enable production of transgene-free varieties for commercialization.We can now solve food security issues by biotechnology applications.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for financial support from the National Transgenic Key Project of the Chinese Natural Science Foundation (2016ZX08010-004,2016ZX08009001),andthe Beijing Natural Science Foundation(6162009).We thank Prof.Long Mao,Institute of Crop Science,CAAS,for critical revision and editing of the manuscript.

R E F E R E N C E S

[1]H.C.Godfray,J.R.Beddington,I.R.Crute,L.Haddad,D.Lawrence,J.F.Muir,J.Pretty,S.Robinson,S.M.Thomas,C.Toulmin,Food security:the challenge of feeding 9 billion people,Science 327(2010)812–818.

[2]P.L.Bhalla,Genetic engineering of wheat-current challenges and opportunities,Trends Biotechnol.24(2006)305–311.

[3]J.Li,X.Ye,B.An,L.Du,H.Xu,Genetic transformation of wheat:current status and future prospects,Plant Biotechnol.Rep.6(2012)183–193.

[4]Y.Ishida,M.Tsunashima,Y.Hiei,T.Komari,Wheat(Triticum aestivum L.),in:K.Wang(Ed.),Methods in Molecular Biology,Agrobacterium Protocols,3rd EdnSpringer Science+Business Media,New York,USA 2014,pp.189–198.

[5]J.San Filippo,P.Sung,H.Klein,Mechanism of eukaryotic homologous recombination,Annu.Rev.Biochem.77(2008)229–257.

[6]M.R.Lieber,The mechanism of double-strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway,Annu.Rev.Biochem.79(2010)181–211.

[7]J.R.Chapman,M.R.Taylor,S.J.Boulton,Playing the end game:DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice,Mol.Cell 47(2012)497–510.

[8]F.G.Jiang,J.A.Doudna,CRISPR-Cas9 structures and mechanisms,Annu.Rev.Biophys.46(2017)505–529.

[9]K.Lowe,E.Wu,N.Wang,G.Hoerster,C.Hastings,M.J.Cho,C.Scelonge,B.Lenderts,M.Chamberlin,J.Cushatt,L.Wang,L.Ryan,T.Khan,J.Chow-Yiu,W.Hua,M.Yu,J.Banh,Z.Bao,K.Brink,E.Igo,B.Rudrappa,P.M.Shamseer,W.Bruce,L.Newman,B.Shen,P.Zheng,D.Bidney,S.C.Falco,I.J.Register,Z.Y.Zhao,D.Xu,T.J.Jones,W.J.Gordon-Kamm,Morphogenic regulators Baby boom and Wuschel improve monocot transformation,Plant Cell(2016)1998–2015.

[10]V.Vasil,A.M.Castillo,M.E.Fromm,I.K.Vasil,Herbicide resistant fertile transgenic wheat plants obtained by microprojectile bombardment of regenerable embryogenic callus,Nat.Biotechnol.10(1992)667–674.

[11]H.J.Xu,J.L.Pang,X.G.Ye,L.P.Du,L.C.Li,Z.Y.Xin,Y.Z.Ma,J.P.Chen,J.Chen,S.H.Cheng,H.Y.Wu,Study on the gene transferring of Nib8 into wheat for its resistance to the yellow mosaic virus by bombardment,Acta Agron.Sin.27(2001)688–693(in Chinese with English abstract).

[12]X.G.Ye,L.Kang,H.J.Xu,L.P.Du,Transferring glucose oxidase gene into wheat by biolistic particles,Acta Agron.Sin.31(2005)686–691(in Chinese with English abstract).

[13]Q.Yao,L.Cong,J.L.Chang,K.X.Li,G.X.Yang,G.Y.He,Low copy number gene transfer and stable expression in a commercial wheat cultivar via particle bombardment,J.Exp.Bot.57(2006)3737–3746.

[14]Q.Yao,L.Cong,G.He,J.Chang,K.Li,G.Yang,Optimization of wheat co-transformation procedure with gene cassettes resulted in an improvement in transformation frequency,Mol.Biol.Rep.34(2007)61–67.

[15]N.N.Shi,G.Y.He,K.X.Li,H.Z.Wang,G.P.Chen,Y.Xu,Transferring a gene expression cassette lacking the vector backbone sequences of the 1Ax1 high molecular weight glutenin subunit into two Chinese hexaploid wheat genotypes,Agric.Sci.China 6(2007)381–390.

[16]L.Chen,Z.Zhang,H.Liang,H.Liu,L.Du,H.Xu,Z.Xin,Overexpression of TiERF1 enhances resistance to sharp eyespot in transgenic wheat,J.Exp.Bot.59(2008)4195–4204.

[17]S.Q.Gao,M.Chen,L.Q.Xia,H.J.Xiu,Z.S.Xu,L.C.Li,C.P.Zhao,X.G.Cheng,Y.Z.Ma,A cotton(Gossypium hirsutum)DRE-binding transcription factor gene,GhDREB,confers enhanced tolerance to drought,high salt,and freezing stresses in transgenic wheat,Plant Cell Rep.28(2009)301–311.

[18]N.Dong,X.Liu,Y.Lu,L.Du,H.Xu,H.Liu,Z.Xin,Z.Zhang,Overexpression of TaPIEP1,a pathogen-induced ERF gene of wheat,confers host-enhanced resistance to fungal pathogen Bipolaris sorokiniana,Funct.Integr.Genomics 10(2010)215–226.

[19]Z.Li,M.Zhou,Z.Zhang,L.Ren,L.Du,B.Zhang,H.Xu,Z.Xin,Expression of a radish defensin in transgenic wheat confers increased resistance to Fusarium graminearum and Rhizoctonia cerealis,Funct.Integr.Genomics 11(2011)63–70.

[20]Z.Zhang,X.Liu,X.Wang,M.Zhou,X.Zhou,X.Ye,X.Wei,An R2R3 MYB transcription factor in wheat,TaPIMP1,mediates host resistance to Bipolaris sorokiniana and drought stresses through regulation of defense-and stress-related genes,New Phytol.196(2012)1155–1170.

[21]M.Chen,L.Sun,H.Wu,J.Chen,Y.Ma,X.Zhang,L.Du,S.Cheng,B.Zhang,X.Ye,J.Pang,X.Zhang,L.Li,I.B.Andika,J.Chen,H.Xu,Durable field resistance to wheat yellow mosaic virus in transgenic wheat containing the antisense virus polymerase gene,Plant Biotechnol.J.12(2014)447–456.

[22]W.Liu,M.Frick,R.Huel,C.L.Nykiforuk,X.Wang,D.A.Gaudet,F.Eudes,R.L.Conner,A.Kuzyk,Q.Chen,Z.Kang,A.Laroche,The stripe rust resistance gene Yr10 encodes an evolutionaryconserved and unique CC-NBS-LRR sequence in wheat,Mol.Plant 7(2014)1740–1755.

[23]L.Gao,S.Wang,X.Y.Li,X.J.Wei,Y.J.Zhang,H.Y.Wang,D.Q.Liu,Expression and functional analysis of a pathogenesisrelated protein 1 gene,TcLr19PR1,involved in wheat resistance against leaf rust fungus,Plant Mol.Biol.Report.33(2015)797–805.

[24]W.Chen,Q.Zhu,H.Wang,J.Xiao,L.Xing,P.Chen,W.Jin,X.E.Wang,Competitive expression of endogenous wheat CENH3 may lead to suppression of alien ZmCENH3 in transgenic wheat× maize hybrids,J.Genet.Genomics 42(2015)639–649.

[25]W.Cheng,X.S.Song,H.P.Li,L.H.Cao,K.Sun,X.L.Qiu,Y.B.Xu,P.Yang,T.Huang,J.B.Zhang,B.Qu,Y.C.Liao,Host-induced gene silencing of an essential chitin synthase gene confers durable resistance to fusarium head blight and seedling blight in wheat,Plant Biotechnol.J.13(2015)1335–1345.

[26]X.He,B.Qu,W.Li,X.Zhao,W.Teng,W.Ma,Y.Ren,B.Li,Z.Li,Y.Tong,The nitrate-inducible NAC transcription factor TaNAC2-5A controls nitrate response and increases wheat yield,Plant Physiol.169(2015)1991–2005.

[27]X.N.Wei,F.D.Shen,Y.T.Hong,W.Rong,L.P.Du,X.Liu,H.J.Xu,L.J.Ma,Z.Y.Zhang,The wheat calcium-dependent protein kinase TaCPK7-D positively regulates host resistance to sharp eyespot disease,Mol.Plant Pathol.17(2016)1252–1264.

[28]X.N.Wei,T.L.Shan,Y.T.Hong,H.J.Xu,X.Liu,Z.Y.Zhang,TaPIMP2,a pathogen-induced MYB protein in wheat,contributes to host resistance to common root rot caused by Bipolaris sorokiniana,Sci.Rep.7(2017)1754.

[29]X.G.Ye,S.Shirley,H.J.Xu,L.P.Du,T.Clement,Regular production of transgenic wheat mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens,Agric.Sci.China 1(2002)239–244.

[30]X.G.Ye,H.M.Cheng,H.J.Xu,L.P.Du,W.Z.Lu,Y.H.Huang,Development of transgenic wheat plants with chitinase and β-1,3-glucosanase genes and their resistance to fusarium head blight,Acta Agron.Sin.31(2005)583–586(in Chinese with English abstract).

[31]X.G.Ye,S.Shirley,H.J.Xu,L.P.Du,Y.H.Huang,W.Z.Lu,T.Clemente,Transformation and identification of BCL and RIP genes related to cell apoptosis into wheat mediated by Agrobacterium,Acta Agron.Sin.31(2005)1389–1393(in Chinese with English abstract).

[32]J.R.Li,W.Zhao,Q.Z.Li,X.G.Ye,B.Y.An,X.Li,X.S.Zhang,RNA silencing of Waxy gene results in low levels of amylose in the seeds of transgenic wheat(Triticum aestivum L.),Acta Genet.Sin.32(2005)846–854(in Chinese with English abstract).

[33]T.J.Zhao,S.Y.Zhao,H.M.Chen,Q.Z.Zhao,Z.M.Hu,B.K.Hou,G.M.Xia,Transgenic wheat progeny resistant to powdery mildew generated by Agrobacterium inoculum to the basal portion of wheat seedlings,Plant Cell Rep.25(2006)1199–1204.

[34]H.Wu,A.Doherty,H.D.Jones,Efficient and rapid Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of durum wheat(Triticum turgidum L.var.durum)using additional virulence genes,Transgenic Res.17(2008)425–436.

[35]L.Ding,S.Li,J.Gao,Y.Wang,G.Yang,G.He,Optimization of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation conditions in mature embryos of elite wheat,Mol.Biol.Rep.36(2009)29–36.

[36]Y.L.Wang,M.X.Xu,G.X.Yin,L.L.Tao,D.W.Wang,X.G.Ye,Transgenic wheat plants derived from Agrobacteriummediated transformation of mature embryo tissues,Cereal Res.Commun.37(2009)1–12.

[37]Y.He,H.D.Jones,S.Chen,X.M.Chen,D.W.Wang,K.X.Li,D.S.Wang,L.Q.Xia,Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of durum wheat(Triticum turgidum L.var.durum cv Stewart)with improved efficiency,J.Exp.Bot.61(2010)1567–1581.

[38]G.P.Wang,X.D.Yu,Y.W.Sun,H.D.Jones,L.Q.Xia,Generation of marker-and/or backbone-free transgenic wheat plants via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation,Front.Plant Sci.7(2016)1324.

[39]K.Wang,H.Y.Liu,L.P.Du,X.G.Ye,Generation of marker-free transgenic hexaploid wheat via an Agrobacterium-mediated co-transformation strategy in commercial Chinese wheat varieties,Plant Biotechnol.J.15(2017)614–623.

[40]T.Richardson,J.Thistleton,T.J.Higgins,C.Howitt,M.Ayliffe,Efficient Agrobacterium transformation of elite wheat germplasm without selection,Plant Cell Tiss.Org.119(2014)647–659.

[41]M.Cheng,J.E.Fry,S.Pang,H.Zhou,C.M.Hironaka,D.R.Duncan,T.W.Conner,Y.Wan,Genetic transformation of wheat mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens,Plant Physiol.115(1997)971–980.

[42]L.L.Tao,G.X.Yin,L.P.Du,Z.Y.Shi,M.Y.She,H.J.Xu,X.G.Ye,Improvement of plant regeneration from immature embryos of wheat infected by Agrobacterium tumefaciens,Agric.Sci.China 10(2011)317–326.

[43]X.M.Wang,X.Ren,G.X.Yin,K.Wang,J.R.Li,L.P.Du,H.J.Xu,X.G.Ye,Effects of environmental temperature on the regeneration frequency of the immature embryos of wheat(Triticum aestivum L.),J.Inter.Agric.13(2014)722–732.

[44]L.Cong,F.A.Ran,D.Cox,S.L.Lin,R.Barretto,N.Habib,P.D.Hsu,X.B.Wu,W.Y.Jiang,L.A.Marraffini,F.Zhang,Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems,Science 339(2013)819–823.

[45]P.Mali,L.H.Yang,K.M.Esvelt,J.Aach,M.Guell,J.E.DiCarlo,J.E.Norville,G.M.Church,RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9,Science 339(2013)823–826.

[46]A.Tovkach,V.Zeevi,T.Tzfira,A toolbox and procedural notes for characterizing novel zinc finger nucleases for genome editing in plant cells,Plant J.57(2009)747–757.

[47]V.M.Bedell,Y.Wang,J.M.Campbell,T.L.Poshusta,C.G.Starker,R.G.Krug,W.Tan,S.G.Penheiter,A.C.Ma,A.Y.Leung,S.C.Fahrenkrug,D.F.Carlson,D.F.Voytas,K.J.Clark,J.J.Essner,S.C.Ekker,In vivo genome editing using a high-efficiency TALEN system,Nature 491(2012)114–118.

[48]Y.Zhang,F.Zhang,X.Li,J.A.Baller,Y.Qi,C.G.Starker,A.J.Bogdanove,D.F.Voytas,Transcription activator-like effector nucleases enable efficient plant genome engineering,Plant Physiol.161(2013)20–27.

[49]J.F.Li,J.E.Norville,J.Aach,M.McCormack,D.Zhang,J.Bush,G.M.Church,J.Sheen,Multiplex and homologous recombination-mediated genome editing in Arabidopsis and Nicotiana benthamiana using guide RNA and Cas9,Nat.Biotechnol.31(2013)688–691.

[50]Y.Li,R.Moore,M.Guinn,L.Bleris,Transcription activatorlike effector hybrids for conditional control and rewiring of chromosomal transgene expression,Sci.Rep.2(2012)897.

[51]J.P.Tremblay,P.Chapdelaine,Z.Coulombe,J.Rousseau,Transcription activator-like effector proteins induce the expression of the frataxin gene,Hum.Gene Ther.23(2012)883–890.

[52]J.D.Sander,J.K.Joung,CRISPR-Cas systems for editing,regulating and targeting genomes,Nat.Biotechnol.32(2014)347–355.

[53]L.S.Qi,M.H.Larson,L.A.Gilbert,J.A.Doudna,J.S.Weissman,A.P.Arkin,W.A.Lim,Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-guided platform for sequence-specific control of gene expression,Cell 152(2013)1173–1183.

[54]A.W.Snowden,P.D.Gregory,C.C.Case,C.O.Pabo,Genespecific targeting of H3K9 methylation is sufficient for initiating repression in vivo,Curr.Biol.12(2002)2159–2166.

[55]A.G.Rivenbark,S.Stolzenburg,A.S.Beltran,X.Yuan,M.G.Rots,B.D.Strahl,P.Blancafort,Epigenetic reprogramming of cancer cells via targeted DNA methylation,Epigenetics 7(2012)350–360.

[56]M.L.Maeder,J.F.Angstman,M.E.Richardson,S.J.Linder,V.M.Cascio,S.Q.Tsai,Q.H.Ho,J.D.Sander,D.Reyon,B.E.Bernstein,J.F.Costello,M.F.Wilkinson,J.K.Joung,Targeted DNA demethylation and activation of endogenous genes using programmable TALE-TET1 fusion proteins,Nat.Biotechnol.31(2013)1137–1142.

[57]E.M.Mendenhall,K.E.Williamson,D.Reyon,J.Y.Zou,O.Ram,J.K.Joung,B.E.Bernstein,Locus-specific editing of histone modifications at endogenous enhancers,Nat.Biotechnol.31(2013)1133–1136.

[58]I.B.Hilton,A.M.D'Ippolito,C.M.Vockley,P.I.Thakore,G.E.Crawford,T.E.Reddy,C.A.Gersbach,Epigenome editing by a CRISPR-Cas9-based acetyltransferase activates genes from promoters and enhancers,Nat.Biotechnol.33(2015)510–517.

[59]Y.Nihongaki,F.Kawano,T.Nakajima,M.Sato,Photoactivatable CRISPR-Cas9 for optogenetic genome editing,Nat.Biotechnol.33(2015)755–760.

[60]Y.Nihongaki,S.Yamamoto,F.Kawano,H.Suzuki,M.Sato,CRISPR-Cas9-based photoactivatable transcription system,Chem.Biol.22(2015)169–174.

[61]L.R.Polstein,C.A.Gersbach,A light-inducible CRISPR-Cas9 system for control of endogenous gene activation,Nat.Chem.Biol.11(2015)198–200.

[62]C.M.Lee,T.J.Cradick,G.Bao,The Neisseria meningitidis CRISPR-Cas9 system enables specific genome editing in mammalian cells,Mol.Ther.24(2016)645–654.

[63]E.Ma,L.B.Harrington,M.R.O'Connell,K.Zhou,J.A.Doudna,Single-stranded DNA cleavage by divergent CRISPR-Cas9 enzymes,Mol.Cell 60(2015)398–407.

[64]F.A.Ran,L.Cong,W.X.Yan,D.A.Scott,J.S.Gootenberg,A.J.Kriz,B.Zetsche,O.Shalem,X.Wu,K.S.Makarova,E.V.Koonin,P.A.Sharp,F.Zhang,In vivo genome editing using Staphylococcus aureus Cas9,Nature 520(2015)186–191.

[65]E.Kim,T.Koo,S.W.Park,D.Kim,K.Kim,H.Y.Cho,D.W.Song,K.J.Lee,M.H.Jung,S.Kim,J.H.Kim,J.H.Kim,J.S.Kim,In vivo genome editing with a small Cas9 orthologue derived from Campylobacter jejuni,Nat.Commun.8(2017)14500.

[66]I.Fonfara,H.Richter,M.Bratovic,A.Le Rhun,E.Charpentier,The CRISPR-associated DNA-cleaving enzyme Cpf1 also processes precursor CRISPR RNA,Nature 532(2016)517–521.

[67]B.Zetsche,J.S.Gootenberg,O.O.Abudayyeh,I.M.Slaymaker,K.S.Makarova,P.Essletzbichler,S.E.Volz,J.Joung,J.van der Oost,A.Regev,E.V.Koonin,F.Zhang,Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system,Cell 163(2015)759–771.

[68]B.Zetsche,M.Heidenreich,P.Mohanraju,I.Fedorova,J.Kneppers,E.M.DeGennaro,N.Winblad,S.R.Choudhury,O.O.Abudayyeh,J.S.Gootenberg,W.Y.Wu,D.A.Scott,K.Severinov,J.van der Oost,F.Zhang,Multiplex gene editing by CRISPR-Cpf1 using a single crRNA array,Nat.Biotechnol.35(2017)31–34.

[69]R.Xu,R.Qin,H.Li,D.Li,L.Li,P.Wei,J.Yang,Generation of targeted mutant rice using a CRISPR-Cpf1 system,Plant Biotechnol.J.15(2017)713–717.

[70]X.Tang,L.G.Lowder,T.Zhang,A.A.Malzahn,X.Zheng,D.F.Voytas,Z.Zhong,Y.Chen,Q.Ren,Q.Li,E.R.Kirkland,Y.Zhang,Y.Qi,A CRISPR-Cpf1 system for efficient genome editing and transcriptional repression in plants,Nat.Plants 3(2017)17103.

[71]L.Liu,P.Chen,M.Wang,X.Li,J.Wang,M.Yin,Y.Wang,C2c1-sgRNA complex structure reveals a RNA-guided DNA cleavage mechanism,Mol.Cell 65(2017)310–322.

[72]O.O.Abudayyeh,J.S.Gootenberg,S.Konermann,J.Joung,I.M.Slaymaker,D.B.Cox,S.Shmakov,K.S.Makarova,E.Semenova,L.Minakhin,K.Severinov,A.Regev,E.S.Lander,E.V.Koonin,F.Zhang,C2c2 is a single-component programmable RNA-guided RNA-targeting CRISPR effector,Science 353(2016)aaf5573.

[73]S.Shmakov,O.O.Abudayyeh,K.S.Makarova,Y.I.Wolf,J.S.Gootenberg,E.Semenova,L.Minakhin,J.Joung,S.Konermann,K.Severinov,F.Zhang,E.V.Koonin,Discovery and functional characterization of diverse class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems,Mol.Cell 60(2015)385–397.

[74]A.East-Seletsky,M.R.O'Connell,S.C.Knight,D.Burstein,J.H.Cate,R.Tjian,J.A.Doudna,Two distinct RNase activities of CRISPR-C2c2 enable guide-RNA processing and RNA detection,Nature 538(2016)270–273.

[75]A.C.Komor,Y.B.Kim,M.S.Packer,J.A.Zuris,D.R.Liu,Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage,Nature 533(2016)420–424.

[76]Z.Shimatani,S.Kashojiya,M.Takayama,R.Terada,T.Arazoe,H.Ishii,H.Teramura,T.Yamamoto,H.Komatsu,K.Miura,H.Ezura,K.Nishida,T.Ariizumi,A.Kondo,Targeted base editing in rice and tomato using a CRISPR-Cas9 cytidine deaminase fusion,Nat.Biotechnol.35(2017)441–443.

[77]Y.Lu,J.K.Zhu,Precise editing of a target base in the rice genome using a modified CRISPR/Cas9 system,Mol.Plant 10(2017)523–525.

[78]Q.W.Shan,Y.P.Wang,K.L.Chen,Z.Liang,J.Li,Y.Zhang,K.Zhang,J.X.Liu,D.F.Voytas,X.L.Zheng,Y.Zhang,C.X.Gao,Rapid and efficient gene modification in rice and Brachypodium using TALENs,Mol.Plant 6(2013)1365–1368.

[79]Y.Wang,X.Cheng,Q.Shan,Y.Zhang,J.Liu,C.Gao,J.L.Qiu,Simultaneous editing of three homoeoalleles in hexaploid bread wheat confers heritable resistance to powdery mildew,Nat.Biotechnol.32(2014)947–951.

[80]Q.Shan,Y.Wang,J.Li,C.Gao,Genome editing in rice and wheat using the CRISPR/Cas system,Nat.Protoc.9(2014)2395–2410.

[81]Y.Zhang,Z.Liang,Y.Zong,Y.P.Wang,J.X.Liu,K.L.Chen,J.L.Qiu,C.X.Gao,Efficient and transgene-free genome editing in wheat through transient expression of CRISPR/Cas9 DNA or RNA,Nat.Commun.7(2016)12617.

[82]Z.Liang,K.Chen,T.Li,Y.Zhang,Y.Wang,Q.Zhao,J.Liu,H.Zhang,C.Liu,Y.Ran,C.Gao,Efficient DNA-free genome editing of bread wheat using CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes,Nat.Commun.8(2017)14261.

[83]Y.Zong,Y.Wang,C.Li,R.Zhang,K.Chen,Y.Ran,J.L.Qiu,D.Wang,C.Gao,Precise base editing in rice,wheat and maize with a Cas9-cytidine deaminase fusion,Nat.Biotechnol.35(2017)438–440.

[84]Q.Zhu,S.Yu,D.Zeng,H.Liu,H.Wang,Z.Yang,X.Xie,R.Shen,J.Tan,H.Li,X.Zhao,Q.Zhang,Y.Chen,J.Guo,L.Chen,Y.G.Liu,Development of“purple endosperm rice”by engineering anthocyanin biosynthesis in the endosperm with a high-efficiency transgene stacking system,Mol.Plant 10(2017)918–929.

[85]A.C.McCormac,M.R.Fowler,D.F.Chen,M.C.Elliott,Efficient co-transformation of Nicotiana tabacum by two independent T-DNAs,the effect of T-DNA size and implications for genetic separation,Transgenic Res.10(2001)143–155.

[86]N.Tuteja,S.Verma,R.K.Sahoo,S.Raveendar,I.N.Reddy,Recent advances in development of marker-free transgenic plants:regulation and biosafety concerns,J.Biosci.37(2012)167–197.

[87]S.Luo,J.Li,T.J.Stoddard,N.J.Baltes,Z.L.Demorest,B.M.Clasen,A.Coffman,A.Retterath,L.Mathis,D.F.Voytas,F.Zhang,Non-transgenic plant genome editing using purified sequence-specific nucleases,Mol.Plant 8(2015)1425–1427.

[88]T.J.Stoddard,B.M.Clasen,N.J.Baltes,Z.L.Demorest,D.F.Voytas,F.Zhang,S.Luo,Targeted mutagenesis in plant cells through transformation of sequence-specific nuclease mRNA,PLoS One 11(2016),e0154634.

[89]J.W.Woo,J.Kim,S.I.Kwon,C.Corvalan,S.W.Cho,H.Kim,S.G.Kim,S.T.Kim,S.Choe,J.S.Kim,DNA-free genome editing in plants with preassembled CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins,Nat.Biotechnol.33(2015)1162–1164.

[90]M.Jinek,K.Chylinski,I.Fonfara,M.Hauer,J.A.Doudna,E.Charpentier,A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity,Science 337(2012)816–821.

[91]S.H.Sternberg,S.Redding,M.Jinek,E.C.Greene,J.A.Doudna,DNA interrogation by the CRISPR RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9,Nature 507(2014)62–67.

[92]F.A.Ran,P.D.Hsu,C.Y.Lin,J.S.Gootenberg,S.Konermann,A.E.Trevino,D.A.Scott,A.Inoue,S.Matoba,Y.Zhang,F.Zhang,Double nicking by RNA-guided CRISPR Cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity,Cell 154(2013)1380–1389.

[93]D.Kim,J.Kim,J.K.Hur,K.W.Been,S.H.Yoon,J.S.Kim,Genome-wide analysis reveals specificities of Cpf1 endonucleases in human cells,Nat.Biotechnol.34(2016)863–868.

[94]K.Zhao,C.W.Tung,G.C.Eizenga,M.H.Wright,M.L.Ali,A.H.Price,G.J.Norton,M.R.Islam,A.Reynolds,J.Mezey,A.M.McClung,C.D.Bustamante,S.R.McCouch,Genome-wide association mapping reveals a rich genetic architecture of complex traits in Oryza sativa,Nat.Commun.2(2011)467.

[95]A.J.Slade,S.I.Fuerstenberg,D.Loeffler,M.N.Steine,D.Facciotti,A reverse genetic,nontransgenic approach to wheat crop improvement by tilling,Nat.Biotechnol.23(2005)75–81.

- The Crop Journal的其它文章

- A journey to understand wheat Fusarium head blight resistance in the Chinese wheat landrace Wangshuibai

- The landscape of molecular mechanisms for salt tolerance in wheat

- Genetic improvement of heat tolerance in wheat:Recent progress in understanding the underlying molecular mechanisms

- Corrigendum to “A new method for evaluating the drought tolerance of upland rice cultivars”[Crop J. 5 (2017) 488–489]

- Mapping stripe rust resistance genes by BSR-Seq:YrMM58 and YrHY1 on chromosome 2AS in Chinese wheat lines Mengmai 58 and Huaiyang 1 are Yr17

- Wheat breeding in the hometown of Chinese Spring