Case of morphine-induced ventricular fibrillation

Roman Skulec, Jitka Callerova, Jiri Knor,4, Petr Ostadal, Petr Kmonicek, Vladimir Cerny

1 Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative Medicine and Intensive Care, J.E. Purkinje University, Masaryk Hospital in Usti nad Labem, Usti nad Labem, Czech Republic

2 Emergency Medical Service of the Central Bohemian Region, Kladno, Czech Republic

3 Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Medicine in Hradec Kralove,University Hospital Hradec Kralove, Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic

4 3rd Medical Faculty, Charles University in Prague, Prague, Czech Republic

5 Cardiovascular Center, Na Homolce Hospital, Prague, Czech Republic

6 Department of Anesthesia, Pain Management and Perioperative Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

7 Department of Research and Development and Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Medicine in Hradec Kralove, University Hospital Hradec Kralove, Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic

Case Letter

Case of morphine-induced ventricular fibrillation

Roman Skulec1,2,3, Jitka Callerova2, Jiri Knor2,4, Petr Ostadal5, Petr Kmonicek5, Vladimir Cerny1,3,6,7

1Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative Medicine and Intensive Care, J.E. Purkinje University, Masaryk Hospital in Usti nad Labem, Usti nad Labem, Czech Republic

2Emergency Medical Service of the Central Bohemian Region, Kladno, Czech Republic

3Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Medicine in Hradec Kralove,University Hospital Hradec Kralove, Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic

43rd Medical Faculty, Charles University in Prague, Prague, Czech Republic

5Cardiovascular Center, Na Homolce Hospital, Prague, Czech Republic

6Department of Anesthesia, Pain Management and Perioperative Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

7Department of Research and Development and Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Medicine in Hradec Kralove, University Hospital Hradec Kralove, Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic

Dear editor,

Morphine is considered as a traditional and safe medication to relieve pain and dyspnea in the setting of acute coronary syndrome and cardiogenic pulmonary edema.[1,2]It is also attributed to dispose an antiarrhythmic effect.[3]We report a case of morphine-induced ventricular fibrillation in the prehospital emergency treatment. The patient presented acute myocardial infarction with ST segment elevations complicated with uncontrolled hypertension and cardiogenic pulmonary edema.

CASE

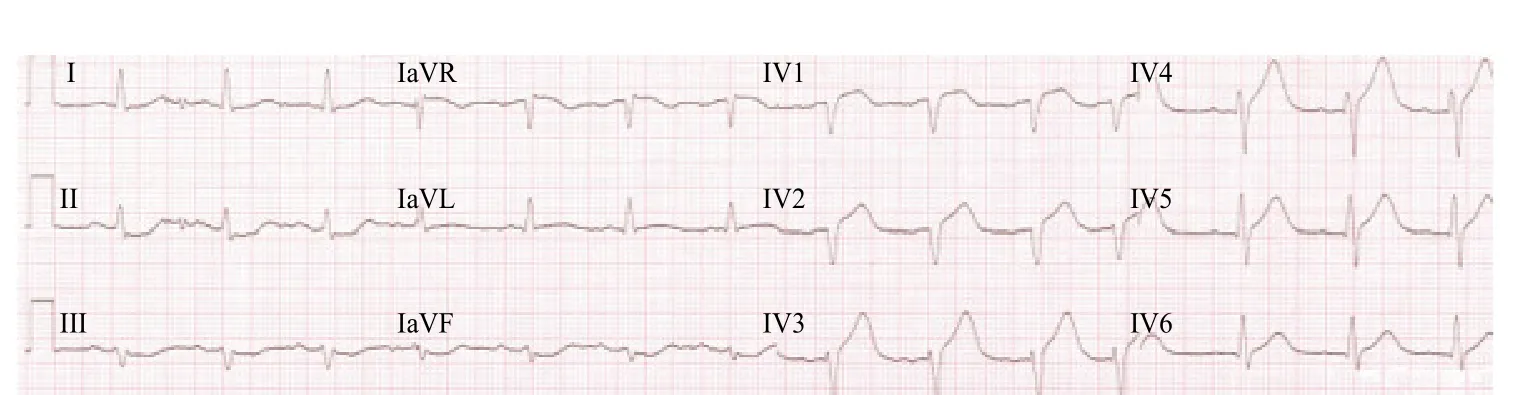

Figure 1. Pre-hospital ECG of the patient, recorded after the first episode of ventricular fibrillation. ST segment elevations in the leads V1, V2, V3, QS wave in the leads V1, V2. PQ interval 200 ms, QRS complex 90 ms, QTc interval 400 ms.

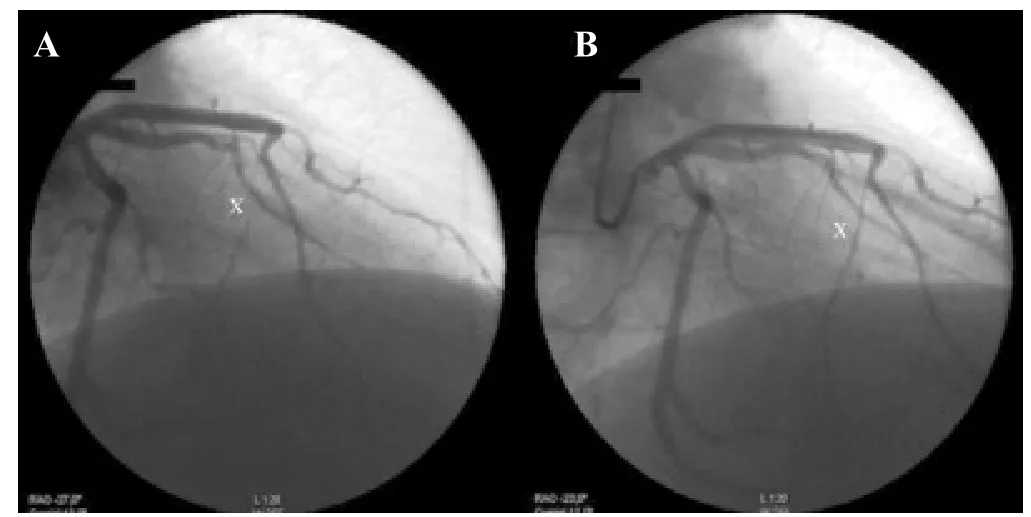

Figure 2. Percutaneous coronary intervention procedure of the presented case. A: Diagnostic coronary angiography of the left coronary artery in left anterior oblique view. “X” shows critical stenosis of septal perforator artery with faint and delayed antegrade coronary flow beyond the occlusion with incomplete filling of the distal coronary bed. B: Coronary angiography after percutaneous balloon coronary angioplasty of culprit lesion with normal fl ow which fills distal coronary bed completely.

A physician-staffed Emergency Medical Service team was sent to a 42-year-old man for shortness of breath. He was found sitting in a chair, dyspneic at rest, pale and sweaty,complaining for chest pain for 30 minutes. Medical history showed arterial hypertension and smoking, chronic treatment with perindopril 4 mg and amlodipine 5 mg once daily in the morning. However, at least 3 days before the patient did not take any medication. He was evaluated as pulmonary edema with hypertension, presenting with tachypnoea (25/minute), hypoxia (peripheral oxygen saturation of 85%),sinus tachycardia (110/minute) and hypertension (blood pressure of 220/130 mmHg). High-flow oxygen therapy by face mask, 3 mg of isosorbiddinitrate and furosemide 40 mg i.v. followed by 4 mg of morphine sulphate i.v.were administered. Fifteen seconds after morphine administration, ventricular fibrillation (VF) developed.The sequence of two immediate defibrillation shocks led to the return of spontaneous circulation and restoration of consciousness. The twelve lead electrocardiogram revealed acute anteroseptal myocardial infarction with ST segment elevations (STEMI, Figure 1). Appropriate therapy was introduced (heparin 10 000 IU, isosorbiddinitrate 4 mg,lysinsalicylic acid 300 mg and clopidogrel 600 mg) and the condition was significantly improved (blood pressure of 130/80 mmHg, heart rate of 80/minute, peripheral oxygen saturation of 96%). The patient was referred for primary percutaneous coronary intervention. For persistent chest pain during transport, 3 mg of morphine i.v. was administered. As previously, approximately 15 seconds after its administration, ventricular fibrillation developed. Immediate defibrillation shock was successful,1 g of MgSO4and 150 mg of amiodarone i.v. were administered and no other morphine was used. For the rest of transport the patient was stable and handed over to the catheterization laboratory. Immediate coronary angiography identified acute occlusion of septal perforator artery with TIMI 1 flow as culprit lesion. It was successfully treated by coronary angioplasty without stent implantation (Figure 2). The further course of the disease was favorable and 8 days later the patient was discharged to the outpatient care. Except of association with prehospital administration of morphine, he had suffered from no further dysrhythmias.

DISCUSSION

The main finding from our experience is that repeated morphine administration in the clinical setting of STEMI accompanied by pulmonary edema with hypertension repeatedly induced ventricular fibrillation.

Morphine is a symptomatic drug recommended for consideration in acute coronary syndrome and/or acute heart failure patients to relieve pain, dyspnea and anxiety.[1,2]Its pleiotropic effect in the patients with coronary artery disease and heart failure include induced decrease of blood pressure and heart rate with various impact on pulmonary circulation and cardiac output, sympatholytic,anxiolytic and analgesic effect and the reduction of subjective feeling of shortness of breath.[4,5]Morphine has been also found to have an protective effect against ischemia and non-ischemia induced ventricular fibrillation.[3,6]However, there have been published clinical studies bringing in controversies about morphine indication in the patients with cardiogenic pulmonary edema regarding increased risk of intubation and mortality.[7]Moreover, case reports and experimental works demonstrating that morphine itself may induce cardiogenic shock and can lead to reversible myocardial dysfunction.[8,9]

On our best knowledge, it is the first report of morphineinduced ventricular fibrillation in the clinical setting of acute myocardial infarction. A complex objective causality assessment using the Naranjo probability scale suggests that the induction of arrhythmia was probably related to morphine.[10]The mechanism of this paradoxical reactions is not precisely known. Nevertheless, there are several suggestions to discuss. First, QT interval prolongation can increase a risk or VF. However, it was not observed in our patient. Second, it can not be excluded that initially,thrombotic occlusion exceeded septal branch to LAD and potential pre-hospital spontaneous reperfusion could trigger ischemia-reperfusion injury leading to presentation by arrhythmic storm. Although this possibility could precipitate observed arrhythmias, in the presented case we stress very close association of VF origin with repeated morphine administration. We also did not observed morphine induced hypotension and/or bradycardia.

Therefore, we hypothesize that a clinical background for this phenomenon could be the presence of severe ongoing ischemia because of coronary artery occlusion,but with preserved minimal blood flow. Morphine administration could lead to an immediate drop in coronary perfusion pressure, thereby worsen ischemia in the area of culprit lesion followed by ischemia induced ventricular fibrillation. Moreover, VF induction was preceded, at least before the second episode, by dramatic blood pressure drop reached by other initial therapy than morphine, which also may have possible impact on the degree of ischemia.

CONCLUSION

Presented case report demonstrates that on the contrary to the general opinion of the antiarrhythmic effect of morphine, its administration in the usual indication, STEMI complicated by cardiogenic pulmonary edema with hypertension can cause serious unexpected and unpredictable adverse effect, ventricular fibrillation. Although it is a very traditional drug, yet we have no reliable evidence which would testify for the use of morphine in emergency treatment of this clinical condition. Conversely, the evidence grows that its use may be associated with a worse prognosis via the worsening of respiratory failure. Moreover, it is only a symptomatic drug. Therefore, we believe that emergency physician should be aware of using morphine as a routine part of the management of cardiovascular emergencies but its use should be individually considered very carefully also for its potential proarrhythmic effect.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of the article.

Contributors: Skulec R proposed the study and wrote the first draft. All authors read and approved the final version of the paper.

1 Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, Badano LP, Lundqvist CB, Borger MA, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(20):2569–619.

2 Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF,Coats AJS, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J.2016;37(27):2129–200.

3 Murphy DB, Murphy MB. Opioid antagonist modulation of ischaemia-induced ventricular arrhythmias: a peripheral mechanism. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1999;33(1):122–5.

4 Lee G, Low RI, Amsterdam EA, DeMaria AN, Huber PW,Mason DT. Hemodynamic effects of morphine and nalbuphine in acute myocardial infarction. Clin Pharmacol Ther.1981;29(5):576–81.

5 Alderman EL, Barry WH, Graham AF, Harrison DC.Hemodynamic effects of morphine and pentazocine differ in cardiac patients. N Engl J Med. 1972;287(13):623–7.

6 EdSilva RA, Verrier RL, Lown B. Protective effect of the vagotonic action of morphine sulphate on ventricular vulnerability. Cardiovasc Res. 1978;12(3):167–72.

7 Peacock WF, Hollander JE, Diercks DB, Lopatin M,Fonarow G, Emerman CL. Morphine and outcomes in acute decompensated heart failure: an ADHERE analysis. Emerg Med J. 2008;25(4):205–9.

8 Feeney C, Ani C, Sharma N, Frohlich T. Morphine-induced cardiogenic shock. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(6):e30.

9 Riggs TR, Yano Y, Vargish T. Morphine depression of myocardial function. Circ Shock. 1986;19(1):31–8.

10 Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA,et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239–45.

Roman Skulec, Email: skulec@email.cz

World J Emerg Med 2017;8(4):310–312

10.5847/wjem.j.1920–8642.2017.04.013

November 12, 2016

Accepted after revision April 9, 2017

World journal of emergency medicine2017年4期

World journal of emergency medicine2017年4期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Evaluation of a point of care ultrasound curriculum for Indonesian physicians taught by first-year medical students

- Instructions for Authors

- Evaluation of modified Alvarado scoring system and RIPASA scoring system as diagnostic tools of acute appendicitis

- Education in cardiopulmonary resuscitation in Russia:A systematic review of the available evidence

- Rehabilitation of vulnerable groups in emergencies and disasters: A systematic review

- Paediatric-appropriate facilities in emergency departments of community hospitals in Ontario:A cross-sectional study