斑马鱼遗传操作进展

高煜,刘家辉,王新,刘东

斑马鱼遗传操作进展

高煜,刘家辉,王新,刘东

南通大学教育部江苏省神经再生重点实验室,江苏南通 226001

高煜, 刘家辉, 王新, 等. 斑马鱼遗传操作进展. 生物工程学报, 2017, 33(10): 1674–1692.Gao Y, Liu JH, Wang X, et al. Genetic manipulation in zebrafish. Chin J Biotech, 2017, 33(10): 1674–1692.

斑马鱼已经成为在发育生物学与疾病模型研究中应用最广泛的实验动物之一,其中多种遗传操作方法和高分辨率活体成像技术对斑马鱼的应用起了重要推动作用。斑马鱼在功能基因组学研究上有许多优势,如可以快速便捷地鉴定脊椎动物新基因的功能。本文尝试以示意图来简要总结应用于斑马鱼的遗传操作方法和基本原理,包括ENU化学诱变筛选的基本原理和隐性突变3代筛选的流程,逆转录病毒介导的插入突变的原理及其隐性突变3代筛选的流程,转座子Sleeping Beauty (SB) 和Tol2介导的基因捕获载体系统 (Gene-breaking transposon,GBT) 为基础的基因捕获突变的基本原理,Morpholino介导的基因下调和microRNA下调技术,TILLING (Targeting induced local lesions in genomes) 技术和CEL1分析的基本原理和实验流程,锌指核酸酶ZFN(Zinc finger nuclease) 与TALEN (Transcription activator-like effector nuclease)、CRISPR/Cas9定向基因失活的基本原理,斑马鱼上广泛采用的转基因技术的几种类型等。

斑马鱼,遗传操作,突变,转基因,转座子,基因编辑

在过去的20多年里,斑马鱼已经成为最广泛应用的实验动物之一,这主要归功于在这种硬骨鱼上胚胎操作、遗传操作的可行性以及近年来流行的高分辨率成像技术。随着斑马鱼在发育生物学与疾病模型等应用领域的扩展,针对斑马鱼的遗传操作方法取得了全新的发展;起源于其他物种的遗传操作方法,如诱变筛选也被引入到斑马鱼上。本文尝试以示意图的方式简要总结应用于斑马鱼的遗传操作方法,对于这些方法的具体实验流程并未涉及,如有需求可查阅相关参考文献。

1 斑马鱼基因组

斑马鱼的基因组为二倍体,由25对染色体组成。这些染色体之间区分困难,其组成DNA大约包含1.4×109个碱基,大致为人类基因组的一半大小[1-2]。据估计,斑马鱼的基因组包含了大约25 000个已知的编码基因以及6 000个非编码基因[2-4]。真哺乳亚纲 (Eutherian) 中不同物种间的基因组非常相似[5-13]。通过荧光原位杂交和比较减数分裂图揭示,在人类、猫、牛、猪和绵羊中整个染色体臂包含了几乎完全相同的一套遗传信息。因此在哺乳动物之间,不仅有同源基因 (Orthologous genes) 还有同源染色体(Orthologous chromosomes)。在一对同源染色体中,基因排列的顺序具有可变性,这也提示在基因组中染色体易位 (Chromosomal translocation)比染色体倒位 (Chromosomal inversion) 发生的频率更高[14]。哺乳动物种间的染色体同源性让我们能够根据一个物种上基因的位置去预测另一个物种同源基因的位置。在进化上,小鼠和人类的最后一个共同的祖先大约在1亿年前,而斑马鱼和人类最后一个共同祖先大约在4亿2千万年前。我们能否用哺乳动物的基因位置来预测斑马鱼的基因位置,或反之?比较基因组学分析显示,斑马鱼与哺乳动物基因组之间的共线性 (Synteny) 高度保守,而且斑马鱼基因组与人类基因组之间的共线性比小鼠与人类基因组之间的共线性更强[15],可能是因为相比其他一些哺乳动物,小鼠的基因组呈现出了大量的重排。斑马鱼和其他硬骨鱼的基因组分析揭示,在硬骨鱼的物种大发生之前,在大量基因丢失之后,斑马鱼基因组经历了一次复制,导致与其他哺乳动物的同源基因相比,斑马鱼中大约30%的基因有两个拷贝,许多人类染色体的片段在斑马鱼中也有两个拷贝,这种现象在基因组的组装和基因功能研究中也得到了印证[16]。在基因组中一个基因有两个位点,针对研究的具体问题来说既可以是优点也可以是缺点。对于大多数已经研究的重复基因来说,其表达调控区域是差异最大的部分。一般观点认为这些重复的基因在功能上是相似的,但它们的时空表达是特异的。这在正向遗传学研究中可以被认为是优点,因为单个基因的突变会产生比较特异的表型;但是,如果这对重复基因时空表达相同或者很相似,就会造成功能的冗余和补偿。当一个基因位点的突变被另一个拷贝所补偿,就会减弱或消除相应的表型,这将增加表型分析的难度。近年来,基于斑马鱼基因组特点,大量遗传学操作策略得以实现,包括正向遗传学、反向遗传学、转基因技术、光遗传学等[17-22]。

2 正向遗传学

传统的遗传学策略大致可分为两类:正向遗传学 (Forward genetics) 和反向遗传学 (Reverse genetics)。正向遗传学是指通过生物个体或细胞的基因组的自发突变或人工诱变,寻找相关表型或性状的改变,然后从这些特定性状变化的个体或细胞中找到对应的突变基因,并揭示其功能[18],包括ENU诱变[23]、插入突变[24]等技术。

2.1 ENU诱变

突变筛选在早期对推动斑马鱼作为模式生物起了重要的作用,其中主要以乙基亚硝基脲 (Ethylnitrosourea,ENU) 诱发突变,其突变率高,从20世纪90年代中期一直延续到现在[25-26]。多数发育异常的表型筛选需要通过几代的交配来得到纯合的隐性突变,显性突变个体在F1代就可以获得,其表型不能是胚胎致死,否则不能遗传到下一代。最早期的斑马鱼ENU大规模诱变筛选开始于两个实验室,一个是位于Tübingen的Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard实验室,另一个是位于Boston/Freiburg的Wolfgang Driever实验室,他们通过显微镜观察,筛选了大量的异常胚胎表型,其中F3代出现了纯合的隐性突变体,其研究结果发表于1996年Development[25,27-28]。突变筛选流程简要描述如图1所示。ENU处理的雄性斑马鱼和野生型雌鱼侧交 (Out-cross),产生大量的F1代个体,培养至成鱼,通过剪尾鳍的方法进行基因型鉴定,筛选突变体。筛选出的F1代可以通过不同的杂交方式产生F2代杂合突变携带者,例如F1代可以在品系内异性自交 (In-cross),增加F2代中突变基因组的数目;也可以用F1代品系与含有遗传多态性标志的完全不同的野生型品系进行侧交,F2代繁殖的后代进行接下来F3代的连锁分析 (Linkage analysis)。F2代个体之间自交将产生许多可以鉴别的胚胎表型,Tübingen和Boston两个研究组得到了超过6 000个突变表型,其中大约1/3与细胞分化、器官发生等有关[27-28],其余的大部分与发育延迟 (Developmental delay or growth retardation) 和坏死 (Necrosis) 相关[29],对一些特异性表型进行分析鉴定,发现了大约600个不连续的位点与原肠胚形成、胚胎图式发生以及器官发生有关[30-31]。

图1 经典的ENU三代隐性突变筛选

2.2 插入突变

2.2.1 逆转录病毒介导的插入突变

插入突变可以利用外源DNA作为诱变剂,而插入的DNA片段可以作为分子标签来鉴定突变基因。插入突变的方法在突变发生技术中有丰富的历史,可以使用多种不同的载体和方法[24]。插入突变的一个关键问题是突变产生的机制。在大多数脊椎动物基因组中外显子一般占1%–2%左右[32],插入基因组的片段要求对基因以及基因表达的产物没有任何影响,或者影响很少。无论选择何种载体,DNA随机插入基因组破坏外显子的几率都不高。突变插入可能有多种原因,例如插入序列提前引入了终止密码子,翻译提前终止,或者表现在RNA水平导致RNA降解[24,33]。在ENU大规模诱变筛选过后不久,MIT的Nancy H Hopkins在斑马鱼上启动了逆转录病毒突变筛选,此方法的基本原理是通过DNA片段的随机插入,破坏基因的正常表达 (图2)[34-35]。这种筛选的优点是导致表型产生的突变基因可以通过PCR来鉴定,比较容易;缺点是这种大片段DNA插入突变的效率远远低于ENU诱导的点突变。插入突变筛选的流程与ENU诱变的流程相似,其筛选流程总结如下 (图3)。在斑马鱼胚胎1-2细胞发育阶段,显微注射外源DNA作为突变剂建立F0代,通过F0代之间的交配,得到用来筛选的F1代[36-37]。从F1代中预筛选出插入拷贝数比较多的,来提高下一代突变的频率。接下来的筛选类似于ENU诱变,但这种筛选与ENU诱变相比需要更大的工作量。

图2 逆转录病毒插入突变的原理

2.2.2 转座子介导的基因捕获突变

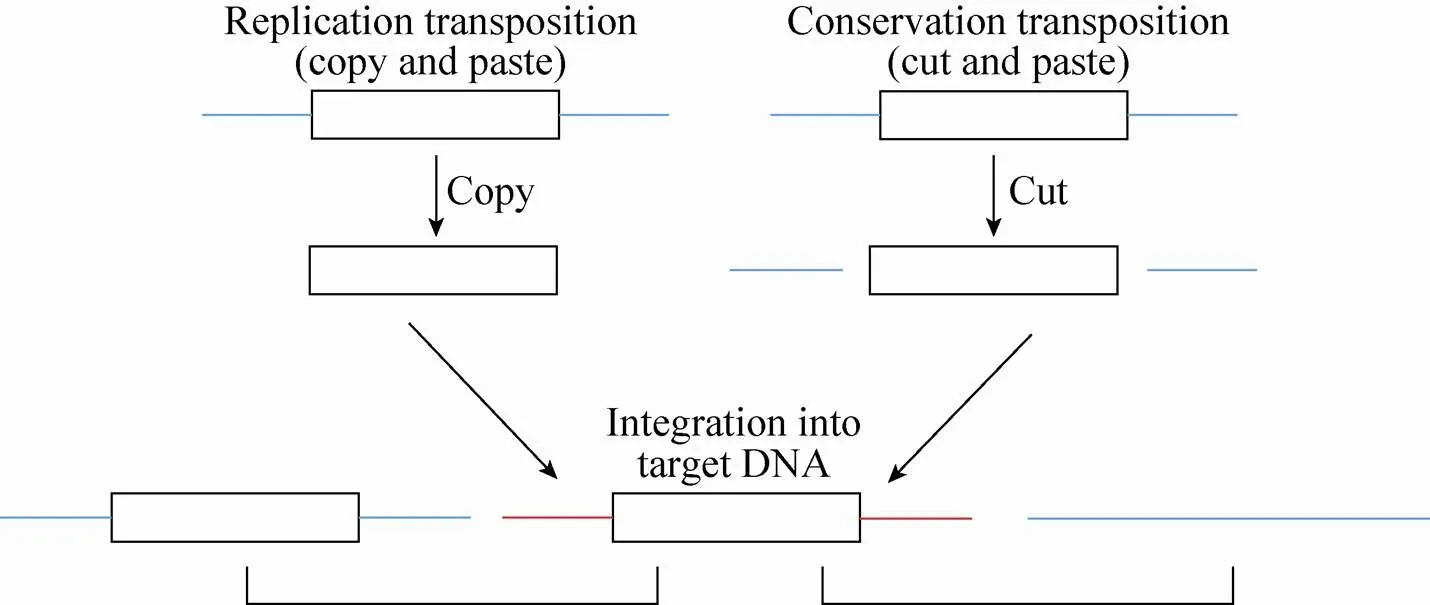

基因捕获突变 (Gene-trap mutagenesis),即通过随机插入报告基因到基因组中来研究基因的功能和表达。这种方法在应用于斑马鱼之前,已经成功地在小鼠上实现捕获调控发育的相关基因、增强子和启动子[38-41]。脊椎动物中Sleeping Beauty (SB) 和Tol2转座子的发现和应用提高了外源DNA整合到基因组的效率[42-43]。在转座酶 (Transposase) 存在的情况下,SB和Tol2载体可以通过“剪切”和“粘贴”机制整合到基因组中 (图4)[44]。一般情况下认为,SB和Tol2插入基因组是随机的方式,但是据一些报道称SB总是插入TA位点,而Tol2没有固定的偏爱的插入位点[45]。目前,SB和Tol2转座子介导的基因捕获突变方法在斑马鱼上得到较好的应用和发展[46-50]。应用于斑马鱼的基因捕获载体 (Gene-breaking transposon,GBT) 系统至少包含一个5′端的突变区和3′端的报告基因区[50],如图5所示。以GBT为基础的载体应用在基因捕获突变中,已经成功地产生了一些隐性突变体,如Tnnt2的突变体,其纯合子斑马鱼胚胎心脏停跳;此外也捕获了一系列基因的表达谱,例如特异表达于大脑、肌肉纤维和心脏等[51]。

图3 逆转录病毒介导的插入突变筛选流程

图4 转座子介导的外源DNA片段插入的两种方式

3 反向遗传学

反向遗传学是相对于正向遗传学而言的,在已知DNA序列的基础上,通过DNA重组、定点突变、插入/缺失等[52-54]遗传学手段构建突变体并研究突变造成的表型,从而研究基因的生物学功能,阐释生命现象和规律[19]。

3.1 Morpholino介导的基因下调和microRNA下调

目前,RNAi在斑马鱼上的应用有待进一步研究[55]。2011年在非洲蟾蜍 (Xenopus) 上的研究发现限制Ago2蛋白活性,能够抑制RNAi和miRNA生物合成,暗示RNAi在斑马鱼上应用的可能性[56],尽管还没有其他研究报道佐证。另一种吗啉环修饰的反义寡核苷酸 (Morpholino,MO) 介导的基因下调方法在非洲蟾蜍 (Xenopus) 和斑马鱼上得到了很好的应用。MO的骨架中吗啉环取代了核苷酸中的脱氧核糖[57-58],MO下调基因表达通常有两种途径:一种是通过与编码区前25个碱基的5′上游互补配对来抑制翻译,另一种是在细胞核内通过与剪切连接点 (Splice junctions) 或者剪切调控位点 (Splice regulatory site) 互补配对来阻止mRNA前体 (Pre-mRNA) 的正确剪切,可以造成外显子丢失、内含子或内含子的一部分保留在剪切产物中 (图6)、移码突变或mRNA的降解[59-60]等。MO下调基因的效率可以通过检测蛋白的表达水平来验证,对于修饰mRNA前体剪切的方式也可以通过RT-PCR来验证[60](图6)。除此之外,MO还可以用来抑制microRNA (miRNA) 的生物合成及其功能[61-62]。MO既可以和miRNA的前体通过碱基互补配对在Dicer或者Drosha的剪切位点形成杂合双链,阻止miRNA前体的剪切 (图7);也可以与miRNA和mRNA作用的靶位点通过碱基互补配对结合,阻止miRNA对其靶分子的调控[63](图7)。但是,MO的应用也有许多的局限性,下调基因表达的方式不是通过稳定的遗传操作,所以其效率很不稳定,而且维持时间也较短。通过显微注射到斑马鱼胚胎中的MO,一般认为只能维持3 d左右[64-65]。通过MO产生的斑马鱼的表型有许多是由于其脱靶效应造成的,MO的显微注射也会在很多情况下导致一些组织的细胞凋亡,实验中可以通过共注射p53的MO来抑制这种副作用[66]。

图5 转座子介导的基因捕获突变

图6 Morpholino介导的基因下调通过两种途径

图7 Morpholino抑制microRNA的生物合成及其功能

3.2 DNA/RNA显微注射

研究基因功能的另一个常见方法就是直接显微注射此基因的mRNA或DNA到单细胞阶段的受精卵中,待发育到一定阶段后分析其表型。所注射的mRNA和DNA可以编码基因的全长、部分功能结构域或者显性负性突变体等。用DNA作为模板体外转录mRNA,注射到1-2细胞阶段的胚胎中可以高效、均一地表达目的蛋白。在许多情况下为了方便检测表达水平,常常将目的基因与报告基因组成融合蛋白,如与绿色荧光蛋白 (GFP) 组成融合蛋白。注射的mRNA一般在受精后4–5 h开始表达,2–4 d后开始降解,因此可以用来研究胚胎发育的早期阶段。DNA最好在单细胞阶段注射到胚胎细胞中,与mRNA注射不同,DNA注射通常产生嵌合表达。在Tol2转座系统存在的情况下可以提高DNA整合及表达效率[45]。

3.3 TILLING

无论是Morpholino还是mRNA显微注射都无法遗传给下一代,为了产生可遗传的突变,建立了一种TILLING (Targeting induced local lesions in genomes) 的反向遗传学技术[67-68]。这种方法利用CEL1分析来检测ENU诱导突变产生的F1个体DNA中的杂合随机突变 (图8A)。CEL1内切酶能够特异性剪切在野生型和突变型杂交DNA双链中单个碱基错配的3′端[69]。从突变体中提取基因组DNA作为PCR的模板来扩增特异的基因,野生型的DNA和突变的DNA都会从杂合子基因组中复制出来。PCR产物片段通过变性和缓慢退火形成杂交的双链。通过CEL1内切酶的消化,DNA片段可以在测序胶上分开,从而确定突变的位点 (图8A),其筛选流程如下 (图8B)。在ENU诱变的F1代中得到精子并冻存,通过CEL1分析鉴定突变的基因,然后可以从精子恢复所需的相应突变体。在TILLING技术的发展过程中,多个实验室起到了重要的推动作用。Hubrecht Institute 建立了4 608个ENU诱导突变的F1代文库,应用TILLING技术已经成功筛选到了16个突变基因[70];Moens实验室报道了运用TILLING技术大规模筛选斑马鱼ENU诱变产生的点突变[23];Sanger研究所也主持了一项基于TILLING技术的斑马鱼突变筛选计划 (Zebrafish mutation project,ZMP),通过大规模ENU诱变的方法获得大量突变位点,构成一个突变位点库,然后根据需要选择特定的基因,通过测序的方法寻找该基因的突变并进行表型检测[71]。在运用TILLING技术时,可能会出现多位点的突变,后代的表型鉴定比较繁琐。目前,TILLING技术运用较少。

图8 CEL1分析和TILLING实验流程

3.4 ZFN/TALEN定向基因失活

在小鼠的胚胎干细胞 (Embryonic stem cell,ESC) 上建立的基因打靶策略 (Gene targeting strategy) 是通过DNA同源重组实现基因的特异性敲除[72-73]。在斑马鱼上已经成功建立了ES样的细胞,并且这些细胞可以贡献到生殖细胞系中并传至下一代[74],但是这种基因打靶策略并没有成功地应用到斑马鱼上产生基因敲除斑马鱼。现在两种定向基因失活技术ZFN和TALEN都已经成功地应用到斑马鱼上[75-79]。锌指核酸酶(Zinc finger nuclease,ZFN)是一种人工改造合成的核酸内切酶,由一个DNA识别结构域 (ZF) 和一个非特异性核酸内切酶结构域 (Fok1) 组成,其中DNA识别结构域能够识别并结合特异的DNA序列,非特异性核酸内切酶具有DNA剪切的功能。通过两个功能结构域的组合就可以在DNA序列的特定靶位点产生双链断裂(Double strand break,DSB)[80-81]。双链断裂通过非同源末端连接 (Nonhomologous end-joining,NHEJ) 和同源重组修复 (Homologous recombination repair,HRR),从而引入小的基因片段,其中非同源末端连接通过随机的删减或添加碱基可以引起移码突变[82]。ZFN的DNA识别结构域是由一连串的Cys2-His2锌指蛋白单位组成,每个锌指蛋白单位能够特异地识别和结合3′到5′方向DNA单链上3个连续的碱基组合 (图9) 和5′到3′方向的1个碱基[83]。当识别DNA双链的一对ZFN的识别位点相距在6到8个碱基之间时 (图9),两个ZFN上的核酸内切酶 (FokI) 结构域形成异二聚体[84]产生核酸酶切功能,达到DNA定向剪切的效果。除了ZFN之外,转录激活因子样核酸酶 (Transcription activator-like effector nuclease,TALEN) 也是一种近来被应用到许多物种的位点特异性的核酸酶[85]。TALEN的组成结构也和ZFN类似,包括非特异性核酸内切酶结构域FokI和DNA识别结构域TALEN[86],TALEN的DNA识别结构域TALEN来自于植物的致病菌黄单胞菌[87],ZFN的每一模块能够识别3个连续碱基,而TALEN每个模块识别1个碱基 (图9)。在斑马鱼上,ZFN和TALEN通过体外转录得到的mRNA后注射到单细胞阶段的受精卵中,筛选并获得靶基因失活的突变体。2011年,北京大学张博教授首次利用TALEN技术在斑马鱼中成功实现可稳定遗传的基因组定点突变[77];2013年又在此基础上,利用TALEN造成的DNA双链断裂,大大提高了同源重组效率,从而在模式生物斑马鱼中实现了真正意义上的同源重组基因打靶[88]。虽然ZFN和TALEN技术均能用于基因定向失活,应用范围有一定的重合,但是这两种技术有各自不同的缺陷。ZFN技术脱靶效率高,设计依赖上下游序列;TALEN技术模块组装过程繁琐、需要大量测序工作、成本高。目前,ZFN和TALEN技术有被CRISPR/Cas9系统取代的趋势。

图9 TALEN和ZFN的工作示意图

3.5 CRISPR/Cas9

CRISPR/Cas9是继ZFN和TALEN之后的第3代RNA介导的定向基因编辑技术,来源于细菌和古细菌的获得性免疫系统[89-91]。具体的原理是:crRNA (CRISPR-derived RNA) 与tracrRNA (Trans-activating RNA) 结合形成tracrRNA/crRNA复合物,引导核酸酶Cas9在与crRNA配对的序列靶位点处剪切双链DNA,形成DSB,通过NHEJ修复机制产生基因序列的缺失或者增加 (图10)。为了简化操作过程,通过人工设计、改造这两种RNA,形成具有导向作用的sgRNA (Single guide RNA),引导Cas9对DNA的定点切割,剪切位点位于sgRNA互补序列下游PAM区 (Protospacer adjacent motif, PAM) 附近,以NGG形式存在(N为任意碱基)[92]。sgRNA设计简单,长度为20个碱基,并且在3′端下游紧邻NGG序列。在2013年1月,张峰率领的研究小组首次证实CRISPR/Cas9系统能够在真核细胞中发挥基因编辑作用[93]。在斑马鱼中,CRISPR/Cas9已被证明可产生基因敲除,Joung实验室首次利用CRISPR/Cas9系统在斑马鱼中实现基因组编辑,他们将特异的sgRNA和Cas9 mRNA共同注射至斑马鱼1细胞期受精卵中,在特定基因位点处检测到碱基缺失和插入的突变[94-95]。同时北京大学熊敬维实验室也报道了CRISPR/Cas9系统在斑马鱼中进行特定基因敲除(Knockout,KO) 的方法,敲除血管发育相关基因,发现突变体血管发育异常,与已有的化学诱变产生的突变体表型一致[96-97]。如果在CRISPR/Cas9系统的基础上引入一个修复的模板质粒,这样能够按照提供的模板在修复过程中引入片段插入,实现基因的敲入。中国科学院上海生命科学研究院神经科学研究所杜久林课题组利用CRISPR/Cas9系统开发出了一种以内含子为基础的基因敲入(Knockin,KI) 方法,将改造的绿色荧光蛋白EGFP的DNA序列插入到斑马鱼() 基因的外显子内,标记内源性蛋白[98-99]。CRISPR/Cas9系统设计简单、成本低廉、制备简便、快捷高效等优点,使其在基因编辑领域得到广泛应用。

图10 CRISPR/Cas9工作示意图

3.6 NgAgo-gDNA

河北科技大学韩春雨实验室报道了一种新的DNA介导的基因编辑系统NgAgo-gDNA (Natronobacterium gregoryi Argonaute,NgAgo),由核酸内切酶NgAgo和具有导向作用的特异性5′-磷酸化的单链DNA (Single-stranded guide DNA,gDNA) 组成,NgAgo结合单链gDNA,并导致靶DNA发生双链断裂[100]。目前NgAgo-gDNA系统存在一些争议,机理还有待于进一步研究[101-102]。我们利用NgAgo-gDNA在斑马鱼中实现了基因敲低 (Knock down,KD),针对斑马鱼基因,设计靶向的第2和第3个外显子5′-磷酸化单链DNA,与NgAgo mRNA共同注射至斑马鱼一细胞期受精卵中,检测到fabp11a mRNA表达水平下降[103]。韩国国立首尔大学Jin-Soo Kim课题组在BioRxiv上发表了他们的研究,通过体外生化实验,发现NgAgo具有DNA依赖的RNA酶活性,并且他们还发现其与NgAgo结合的DNA (Guide oligodeoxyribonucleotides,gODNs) 序列必须与RNA反向互补,而正义DNA (Sense DNA) 序列则不能引导NgAgo切割靶RNA。

4 转基因

以显微注射为基础的转基因技术是利用斑马鱼为模式生物研究的有力工具。在转基因生物中,外源基因被整合到宿主基因组中,在子代稳定遗传。目前有多种方法可以获得转基因斑马鱼,其中一种方法就是向斑马鱼受精卵中注入外源DNA,培养至成鱼,然后从中筛选出整合了外源基因的转基因品系。这种方法效率不高,但是因为显微注射和表型筛选容易,以前常被采用。一般来说,显微注射外源性DNA的斑马鱼中大约5%有外源基因整合,这些嵌合体中又有约5%的可以将外源基因传到下一代。这个概率取决于许多因素,包括外源性表达载体的结构、DNA注入量以及操作者的技能。转基因斑马鱼遵循孟德尔遗传规律。表型筛选可以利用荧光蛋白 (例如GFP) 的表达来鉴定,也可能需要PCR来鉴定。通过简单的DNA注射方法实现的转基因通常含有多个目的基因的串联拷贝。多拷贝转基因可以提高目的基因表达效率,但有时根据目的也需要单拷贝插入。近年来发展出的转座子系统Tol2[45]和Sleeping Beauty[46],可以实现单拷贝插入,相比简单的显微注射效率提高很多。提高目的基因拷贝插入效率也可以使用核酸酶Ⅰ-SceⅠ[104]来实现,其基本原理如图11所示。

利用转基因技术研究基因功能的一个常见问题就是转基因可能引起的显性致死,无法建立稳定的转基因品系。解决这个问题的方法有多种,包括基因诱导表达和双组分系统 (Binary systems),即通过两个转基因品系的交配来实现目的基因的表达 (图12C、D)。基因诱导表达体系通常含有一个在正常情况下处于沉默状态的转基因,当在一些外部因素刺激下这个基因才启动表达。例如,28.5 ℃时斑马鱼热休克蛋白HSP70的启动子在所有组织中 (除了晶状体之外) 有很低的活性[105-106],Hsp70的表达可以被高温激活,即37 ℃热处理胚胎1 h可激活Hsp70活性。通过使用聚焦激光局部加热的方法也可以诱导Hsp70在局部表达[107]。另外使用糖皮质类固醇也可以实现斑马鱼转基因的诱导表达[108]。双组分系统利用两个独立的转基因品系的交配来调控基因表达。在GAL4/UAS系统中,转基因斑马鱼在组织特异性启动子调控下表达酵母转录因子GAL4,另一个外源基因由含有UAS序列的启动子驱动,它在没有外在因素刺激下是沉默的,而当GAL4识别UAS序列时,启动外源基因表达。GAL4/UAS系统的建立可以方便地实现多种遗传操作[109](图12C)。另一个双组分系统由位点特异性重组酶Cre和其识别序列loxP组成。如图12D所示,Cre重组酶作用之前表达一个基因 (目标基因cDNA1),Cre重组酶作用之后调控表达另一个基因 (目标基因cDNA2),这种转变通过Cre重组酶和loxP序列相互作用所调控[110],现在基因诱导表达和双组分系统可以组合起来应用图12E。除此之外基因诱导表达和双组分系统还有一些其他类型,其原理各不相同,但是最终可以实现相似的目的,在此不作一一介绍。

图11 用Ⅰ-SceⅠ来产生转基因斑马鱼

图12 转基因表达系统

目前常用于生命科学研究的模式生物有酵母、线虫、果蝇、斑马鱼、小鼠等,相关遗传操作技术发展迅速,各有优势。例如,模式生物秀丽隐杆线虫是多细胞无脊椎动物,在自然状态下具有雄性和雌雄同体这两种性别特征,在遗传研究上具有无可比拟的优势,突变体筛选效率高[20];小鼠属于哺乳动物,生理和发育过程与人类相似,基因组与人类高度同源,能够在ES细胞上进行遗传操作,利用同源重组构建基因敲除系[111-112]。

近年来,斑马鱼作为一种重要的模式生物,也被广泛地运用于生命科学研究,其易于在实验室内繁育,一般每周可以产卵一次,每次有100–300枚,遗传学操作和筛选十分方便。这些遗传操作方法在斑马鱼上的单一使用以及组合使用大大增强了斑马鱼作为模式生物的优势。同时,一些新技术的出现必将进一步推动其在发育生物学与疾病模型上的应用,例如光遗传学 (Optogenetics)。光遗传学将重组DNA技术与光学技术结合起来,成为细胞生物学研究的有力工具,用于活细胞内目标蛋白质的跟踪以及选择性地控制某类细胞特定的生物学活动[113]。斑马鱼作为胚胎通体透明的模式动物则更是理想的运用光遗传学开展研究的对象[114],2010年Didier YR Stainier 实验室成功实现了利用光来控制心脏的功能[115]。斑马鱼模型上丰富的遗传操作策略将越来越帮助我们认识生命过程、揭示生命的奥秘。

[1] Fishman MC. Genomics. Zebrafish--the canonical vertebrate. Science, 2001, 294(5545): 1290–1291.

[2] Postlethwait J, Amores A, Force A, et al. The zebrafish genome. Methods Cell Biol, 1999, 60: 149–163.

[3] Howe K, Clark MD, Torroja CF, et al. The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature, 2013, 496(7446): 498–503.

[4] Postlethwait JH, Woods IG, Ngo-Hazelett P, et al. Zebrafish comparative genomics and the origins of vertebrate chromosomes. Genome Res, 2000, 10(12): 1890–1902.

[5] Rettenberger G, Klett C, Zechner U, et al. ZOO-FISH analysis: cat and human karyotypes closely resemble the putative ancestral mammalian karyotype. Chromosome Res, 1995, 3(8): 479–486.

[6] Rettenberger G, Klett C, Zechner U, et al. Visualization of the conservation of synteny between humans and pigs by heterologous chromosomal painting. Genomics, 1995, 26(2): 372–378.

[7] Solinas-Toldo S, Lengauer C, Fries R. Comparative genome map of human and cattle. Genomics, 1995, 27(3): 489–496.

[8] O'Brien SJ, Cevario SJ, Martenson JS, et al. Comparative gene mapping in the domestic cat (). J Hered, 1997, 88(5): 408–414.

[9] Jiang Y, Xie M, Chen WB, et al. The sheep genome illuminates biology of the rumen and lipid metabolism. Science, 2014, 344(6188): 1168–1173.

[10] Keane M, Semeiks J, Webb AE, et al. Insights into the evolution of longevity from the bowhead whale genome. Cell Rep, 2015, 10(1): 112–122.

[11] Ai HS, Fang XD, Yang B, et al. Adaptation and possible ancient interspecies introgression in pigs identified by whole-genome sequencing. Nat Genet, 2015, 47(3): 217–225.

[12] Agaba M, Ishengoma E, Miller WC, et al. Giraffe genome sequence reveals clues to its unique morphology and physiology. Nat Commun, 2016, 7: 11519.

[13] Gordon D, Huddleston J, Chaisson MJP, et al. Long-read sequence assembly of the gorilla genome. Science, 2016, 352(6281): aae0344.

[14] Watkins-Chow DE, Buckwalter MS, Newhouse MM, et al. Genetic mapping of 21 genes on mouse chromosome 11 reveals disruptions in linkage conservation with human chromosome 5. Genomics, 1997, 40(1): 114–122.

[15] Postlethwait JH, Yan YL, Gates MA, et al. Vertebrate genome evolution and the zebrafish gene map. Nat Genet, 1998, 18(4): 345–349.

[16] Postlethwait J, Amores A, Cresko W, et al. Subfunction partitioning, the teleost radiation and the annotation of the human genome. Trends Genet, 2004, 20(10): 481–490.

[17] Deisseroth K. Optogenetics. Nat Methods, 2011, 8(1): 26–29.

[18] Peters JL, Cnudde F, Gerats T. Forward genetics and map-based cloning approaches. Trends Plant Sci, 2003, 8(10): 484–491.

[19] Huang P, Zhu ZY, Lin S, et al. Reverse genetic approaches in zebrafish. J Genet Genomics, 2012, 39(9): 421–433.

[20] Kutscher LM, Shaham S. Forward and reverse mutagenesis in.. WormBook, 2014: 1–26.

[21] Besnard F, Koutsovoulos G, Dieudonne S, et al. Toward universal forward genetics: using a draft genome sequence of the nematode oscheius tipulae to identify mutations affecting vulva developmen. Genetics, 2017, 206(4): 1741–1761.

[22] Besnard F, Koutsovoulos G, Dieudonné S, et al. Construction of a series of pCS2+ backbone-based Gateway vectors for overexpressing various tagged proteins in vertebrates. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai), 2016, 48(12): 1128–1134.

[23] Draper BW, McCallum CM, Stout JL, et al. A high-throughput method for identifying N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)-induced point mutations in zebrafish. Methods Cell Biol, 2004, 77: 91–112.

[24] Sivasubbu S, Balciunas D, Amsterdam A, et al. Insertional mutagenesis strategies in zebrafish. Genome Biol, 2007, 8(S1): S9.

[25] Mullins MC, Hammerschmidt M, Haffter P, et al. Large-scale mutagenesis in the zebrafish: in search of genes controlling development in a vertebrate. Curr Biol, 1994, 4(3): 189–202.

[26] Solnica-Krezel L, Schier AF, Driever W. Efficient recovery of ENU-induced mutations from the zebrafish germline. Genetics, 1994, 136(4): 1401–1420.

[27] Driever W, Solnica-Krezel L, Schier AF, et al. A genetic screen for mutations affecting embryogenesis in zebrafish. Development, 1996, 123(1): 37–46.

[28] Haffter P, Granato M, Brand M, et al. The identification of genes with unique and essential functions in the development of the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Development, 1996, 123(1): 1–36.

[29] Kim SH, Wu SY, Baek JI, et al. A post-developmental genetic screen for zebrafish models of inherited liver disease. PLoS ONE, 2015, 10(5): e0125980.

[30] Kur E, Christa A, Veth KN, et al. Loss of Lrp2 in zebrafish disrupts pronephric tubular clearance but not forebrain development. Dev Dyn, 2011, 240(6): 1567–1577.

[31] Jiang F, Chen J, Ma X, et al. Analysis of mutants from a genetic screening reveals the control of intestine and liver development by many common genes in zebrafish. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2015, 8, 460(3): 838–844.

[32] Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science, 2001, 291(5507): 1304–1351.

[33] Amsterdam A, Becker TS. Transgenes as screening tools to probe and manipulate the zebrafish genome. Dev Dyn, 2005, 234(2): 255–268.

[34] Golling G, Amsterdam A, Sun ZX, et al. Insertional mutagenesis in zebrafish rapidly identifies genes essential for early vertebrate development. Nat Genet, 2002, 31(2): 135–140.

[35] Amsterdam A, Hopkins N. Retroviral-mediated insertional mutagenesis in zebrafish. Methods Cell Biol, 2004, 77: 3–20.

[36] Amsterdam A, Burgess S, Golling G, et al. A large-scale insertional mutagenesis screen in zebrafish. Genes Dev, 1999, 13(20): 2713–2724.

[37] Lin S, Gaiano N, Culp P, et al. Integration and germ-line transmission of a pseudotyped retroviral vector in zebrafish. Science, 1994, 265(5172): 666–669.

[38] Stanford WL, Caruana G, Vallis KA, et al. Expression trapping: identification of novel genes expressed in hematopoietic and endothelial lineages by gene trapping in ES cells. Blood, 1998, 92(12): 4622–4631.

[39] Korn R, Schoor M, Neuhaus H, et al. Enhancer trap integrations in mouse embryonic stem cells give rise to staining patterns in chimaeric embryos with a high frequency and detect endogenous genes. Mech Dev, 1992, 39(1/2): 95–109.

[40] Friedrich G, Soriano P. Promoter traps in embryonic stem cells: a genetic screen to identify and mutate developmental genes in mice. Genes Dev, 1991, 5(9): 1513–1523.

[41] Ni TT, Lu J, Zhu M, et al. Conditional control of gene function by an invertible gene trap in zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2012, 109(38):15389–15394.

[42] Ivics Z, Kaufman CD, Zayed H, et al. The Sleeping Beauty transposable element: evolution, regulation and genetic applications. Curr Issues Mol Biol, 2004, 6(1): 43–55.

[43] Kawakami K, Koga A, Hori H, et al. Excision of the Tol2 transposable element of the medaka fish, Oryzias latipes, in zebrafish, Danio rerio. Gene, 1998, 225(1/2): 17–22.

[44] Ivics Z, Li MA, Mátés L, et al. Transposon-mediated genome manipulation in vertebrates. Nat Methods, 2009, 6(6): 415–422.

[45] Kawakami K. Transposon tools and methods in zebrafish. Dev Dyn, 2005, 234(2): 244–254.

[46] Balciunas D, Davidson AE, Sivasubbu S, et al. Enhancer trapping in zebrafish using the Sleeping Beauty transposon. BMC Genomics, 2004, 5(1): 62.

[47] Kawakami K, Hisashi T, Noriko N, et al. A transposon-mediated gene trap approach identifies developmentally regulated genes in zebrafish. Dev Cell, 2004, 7(1): 133–144.

[48] Parinov S, Kondrichin I, Korzh V, et al. Tol2 transposon-mediated enhancer trap to identify developmentally regulated zebrafish genes. Dev Dyn, 2004, 231(2): 449–459.

[49] Balciunas D, Wangensteen KJ, Wilber A, et al. Harnessing a high cargo-capacity transposon for genetic applications in vertebrates. PLoS Genet, 2006, 2(11): e169.

[50] Sivasubbu S, Balciunas D, Davidson AE, et al. Gene-breaking transposon mutagenesis reveals an essential role for histone H2afza in zebrafish larval development. Mech Dev, 2006, 123(7): 513–529.

[51] Maddison LA1, Li M, Chen W. Conditional gene-trap mutagenesis in zebrafish. Methods Mol Biol, 2014, 1101: 393–411.

[52] Manis JP. Knock out, knock in, knock down—genetically manipulated mice and the Nobel Prize. N Engl J Med, 2007, 357(24): 2426–2429.

[53] Schween G, Egener T, Fritzowsky D, et al. Large-scale analysis of 73 329 Physcomitrella plants transformed with different gene disruption libraries: production parameters and mutant phenotypes. Plant Biol, 2005, 7(3): 228–237.

[54] Islam K. Allele-specific chemical genetics: concept, strategies, and applications. ACS Chem Biol, 2015, 10(2):343–363.

[55] Skromne I, Prince VE. Current perspectives in zebrafish reverse genetics: moving forward. Dev Dyn, 2008, 237(4): 861–882.

[56] Lund E, Sheets MD, Imboden SB, et al. Limiting Ago protein restricts RNAi and microRNA biogenesis during early development in. Genes Dev, 2011, 25(11): 1121–1131.

[57] Summerton J, Weller D. Morpholino antisense oligomers: design, preparation, and properties. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev, 1997, 7(3): 187–195.

[58] Summerton J. Morpholino antisense oligomers: the case for an RNase H-independent structural type. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1999, 1489(1): 141–158.

[59] Nasevicius A, Ekker SC. Effective targeted gene 'knockdown' in zebrafish. Nat Genet, 2000, 26(2): 216–220.

[60] Draper BW, Morcos A, Kimmel CB. Inhibition of zebrafish fgf8 pre-mRNA splicing with morpholino oligos: a quantifiable method for gene knockdown. Genesis, 2001, 30(3): 154–156.

[61] Flynt AS, Li N, Thatcher EJ, et al. Zebrafish miR-214 modulates Hedgehog signaling to specify muscle cell fate. Nat Genet, 2007, 39(2): 259–263.

[62] Kloosterman WP, Lagendijk AK, Ketting RF, et al. Targeted inhibition of miRNA maturation with morpholinos reveals a role for miR-375 in pancreatic islet development. PLoS Biol, 2007, 5(8): e203.

[63] Choi WY, Giraldez AJ, Schier AF. Target protectors reveal dampening and balancing of Nodal agonist and antagonist by miR-430. Science, 2007, 318(5848): 271–274.

[64] Bill BR, Petzold AM, Clark KJ, et al. A primer for morpholino use in zebrafish. Zebrafish, 2009, 6(1): 69–77.

[65] Smart EJ, De Rose RA, Farber SA. Annexin 2-caveolin 1 complex is a target of ezetimibe and regulates intestinal cholesterol transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2004, 101(10): 3450–3455.

[66] Robu ME, Larson JD, Nasevicius A, et al. p53 activation by knockdown technologies. PLoS Genet, 2007, 3(5): e78.

[67] McCallum CM, Comai L, Greene EA, et al. Targeted screening for induced mutations. Nat Biotechnol, 2000, 18(4): 455–457.

[68] Wienholds E, Schulte-Merker S, Walderich B, et al. Target-selected inactivation of the zebrafish rag1 gene. Science, 2002, 297(5578): 99–102.

[69] Oleykowski CA, Bronson Mullins CR, Godwin AK, et al. Mutation detection using a novel plant endonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res, 1998, 26(20): 4597–4602.

[70] Wienholds E, van Eeden F, Kosters M, et al. Efficient target-selected mutagenesis in zebrafish. Genome Res, 2003, 13(12): 2700–2707.

[71] Kettleborough RNW, Busch-Nentwich EM, Harvey SA, et al. A systematic genome-wide analysis of zebrafish protein-coding gene function. Nature, 2013, 496(7446): 494–497.

[72] Capecchi MR. Altering the genome by homologous recombination. Science, 1989, 244(4910): 1288–1292.

[73] Thompson S, Clarke AR, Pow AM, et al. Germ line transmission and expression of a corrected HPRT gene produced by gene targeting in embryonic stem cells. Cell, 1989, 56(2): 313–321.

[74] Ma CG, Fan LC, Ganassin R, et al. Production of zebrafish germ-line chimeras from embryo cell cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2001, 98(5): 2461–2466.

[75] Meng XD, Noyes MB, Zhu LJ, et al. Targeted gene inactivation in zebrafish using engineered zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol, 2008, 26(6): 695–701.

[76] Doyon Y, McCammon JM, Miller JC, et al. Heritable targeted gene disruption in zebrafish using designed zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol, 2008, 26(6): 702–708.

[77] Huang P, Xiao A, Zhou MG, et al. Heritable gene targeting in zebrafish using customized TALENs. Nat Biotechnol, 2011, 29(8): 699–700.

[78] Sander JD, Cade L, Khayter C, et al. Targeted gene disruption in somatic zebrafish cells using engineered TALENs. Nat Biotechnol, 2011, 29(8): 697–698.

[79] Wood AJ, Lo TW, Zeitler B, et al. Targeted genome editing across species using ZFNs and TALENs. Science, 2011, 333(6040): 307.

[80] Bibikova M, Carroll D, Segal DJ, et al. Stimulation of homologous recombination through targeted cleavage by chimeric nucleases. Mol Cell Biol, 2001, 21(1): 289–297.

[81] Händel EM, Alwin S, Cathomen T. Expanding or restricting the target site repertoire of zinc-finger nucleases: the inter-domain linker as a major determinant of target site selectivity. Mol Ther, 2009, 17(1): 104–111.

[82] Durai S, Mani M, Kandavelou K, et al. Zinc finger nucleases: custom-designed molecular scissors for genome engineering of plant and mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res, 2005, 33(18): 5978–5990.

[83] Pabo CO, Peisach E, Grant RA. Design and selection of novel Cys2His2zinc finger proteins. Annu Rev Biochem, 2001, 70: 313–340.

[84] Bitinaite J, Wah DA, Aggarwal AK, et al. FokI dimerization is required for DNA cleavage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1998, 95(18): 10570–10575.

[85] Li T, Huang S, Zhao XF, et al. Modularly assembled designer TAL effector nucleases for targeted gene knockout and gene replacement in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res, 2011, 39(14): 6315–6325.

[86] Baker M. Gene-editing nucleases. Nat Methods, 2012, 9(1): 23–26.

[87] Moscou MJ, Bogdanove AJ. A simple cipher governs DNA recognition by TAL effectors. Science, 2009, 326(5959): 1501.

[88] Zu Y, Tong XJ, Wang ZX, et al. TALEN-mediated precise genome modification by homologous recombination in zebrafish. Nat Methods, 2013, 10(4): 329–331.

[89] Mali P, Esvelt KM, Church GM. Cas9 as a versatile tool for engineering biology. Nat Methods, 2013, 10(10): 957–963.

[90] Carter J, Wiedenheft B. SnapShot: CRISPR-RNA-guided adaptive immune systems. Cell, 2015, 163(1): 260–260.e1.

[91] Ramanan V, Shlomai A, Cox DB, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 cleavage of viral DNA efficiently suppresses hepatitis B virus. Sci Rep, 2015, 5: 10833.

[92] Chari R, Yeo NC, Chavez A, et al. sgRNA Scorer 2.0: A species-independent model to predict CRISPR/Cas9 activity. ACS Synth Biol. 2017, 6(5):902–904.

[93] Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science, 2013, 339(6121): 819–823.

[94] Hwang WY, Fu YF, Reyon D, et al. Efficient genome editing in zebrafish using a CRISPR-Cas system. Nat Biotechnol, 2013, 31(3): 227–229.

[95] Zhang F, Wen Y, Guo X. CRISPR/Cas9 for genome editing: progress, implications and challenges. Hum Mol Genet, 2014, 23(R1): 40–46.

[96] Chang NN, Sun CH, Gao L, et al. Genome editing with RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease in Zebrafish embryos. Cell Res, 2013, 23(4): 465–472.

[97] Huang X, Zhou G, Wu W, et al. Genome editing abrogates angiogenesis. Nat Commun, 2017, 8(1):112.

[98] Li J, Zhang BB, Ren YG, et al. Intron targeting-mediated and endogenous gene integrity-maintaining knockin in zebrafish using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Cell Res, 2015, 25(5): 634–637.

[99] Li J, Zhang BB, Bu JW, et al. Intron-based genomic editing: a highly efficient method for generating knockin zebrafish. Oncotarget, 2015, 6(20): 17891–17894.

[100] Gao F, Shen XZ, Jiang F, et al. DNA-guided genome editing using the Natronobacterium gregoryi Argonaute. Nat Biotechnol, 2016, 34(7): 768–773.

[101] Cyranoski D. Replications, ridicule and a recluse: the controversy over NgAgo gene-editing intensifies. Nature, 2016, 536(7615): 136–137.

[102] Cyranoski D. Updated: NgAgo gene-editing controversy escalates in peer-reviewed papers. Nature, 2016, 540(7631): 20–21.

[103] Qi JL, Dong ZJ, Shi YW, et al. NgAgo-based fabp11a gene knockdown causes eye developmental defects in zebrafish. Cell Res, 2016, 26(12): 1349–1352.

[104] Grabher C, Joly JS, Wittbrodt J. Highly efficient zebrafish transgenesis mediated by the meganuclease I-SceI. Methods Cell Biol, 2004, 77: 381–401.

[105] Blechinger SR, Evans TG, Tang PT, et al. The heat-inducible zebrafish hsp70 gene is expressed during normal lens development under non-stress conditions. Mech Dev, 2002, 112(1/2): 213–215.

[106] Evans TG, Yamamoto Y, Jeffery WR, et al. Zebrafish Hsp70 is required for embryonic lens formation. Cell Stress Chaperones, 2005, 10(1): 66–78.

[107] Halloran MC, Sato-Maeda M, Warren JT, et al. Laser-induced gene expression in specific cells of transgenic zebrafish. Development, 2000, 127(9): 1953–1960.

[108] de Graaf M, Zivkovic D, Joore J. Hormone-inducible expression of secreted factors in zebrafish embryos. Dev Growth Differ, 1998, 40(6): 577–582.

[109] Scheer N, Campos-Ortega JA. Use of the Gal4-UAS technique for targeted gene expression in the zebrafish. Mech Dev, 1999, 80(2): 153–158.

[110] Dong J, Stuart GW. Transgene manipulation in zebrafish by using recombinases. Methods Cell Biol, 2004, 77: 363–379.

[111] Sung YH, Baek IJ, Seong JK, et al. Mouse genetics: catalogue and scissors. BMB Rep, 2012, 45(12): 686–692.

[112] Horii T, Hatada I. Genome editing using mammalian haploid cells. Int J Mol Sci, 2015, 16(10): 23604–23614.

[113] Wyart C, Del Bene F, Warp E, et al. Optogenetic dissection of a behavioural module in the vertebrate spinal cord. Nature, 2009, 461(7262): 407–410.

[114] Simmich J, Staykov E, Scott E. Zebrafish as an appealing model for optogenetic studies. Prog Brain Res, 2012, 196: 145–162.

[115] Arrenberg AB, Stainier DYR, Baier H, et al. Optogenetic control of cardiac function. Science, 2010, 330(6006): 971–974.

(本文责编 郝丽芳)

Genetic manipulation in zebrafish

Yu Gao, Jiahui Liu, Xin Wang, and Dong Liu

MOE Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Neuroregeneration, Nantong University, Nantong 226001, Jiangsu, China

The increasing number of genetic manipulation approaches and high-resolution live imaging technique applied in zebrafish have propelled the rise of this organism as a mainstream model for developmental biology and human diseases studies. Zebrafish has many advantages for functional genomics analysis, allowing for easy, cheap and fast functional characterization of novel genes in the vertebrate genome. Here we provide an overview of the principles of genetic manipulation in zebrafish, such as Ethylnitrosourea (ENU) mutagenesis, insertional mutagenesis, gene trapping mutagenesis, Morpholino mediated gene knockdown, targeting induced local lesions in genomes (TILLING), genome editing with engineered nucleases ZFN (Zinc finger nuclease), TALEN (Transcription activator-like effector nuclease) and CRISPR/Cas9 system, and transgenic methods used in zebrafish.

zebrafish, genetic manipulation, mutation, transgenic, transposon, gene editing

May 5, 2017;

August 31, 2017

Dong Liu. Tel: +86-513-85051593; Fax: +86-513-85511585; E-mail: liudongtom@gmail.com

Supported by:Postgraduate Research Notation Project of Jiangsu Province Ordinary University (No. KYLX16-0964).

2017-09-06

网络出版地址:http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.1998.Q.20170906.1058.003.html

江苏省普通高校学术学位研究生科研创新计划项目 (No. KYLX16-0964) 资助。

刘东 博士。于2011年获德国马克斯-德尔布吕克分子医学中心(Max-Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine)/柏林自由大学 (Free University of Berlin)自然科学博士学位。从2012年8月起任南通大学神经再生重点实验室副教授。现为中国解剖学会再生医学专业委员会委员,江苏省发育与细胞学会理事,江苏省神经科学会理事。主要研究方向为:1) 鉴定参与血管新生以及神经系统发育过程中的全新的调控分子。2) 组织再生过程中血管化的过程及调控机制。3) 利用多种遗传操作技术建立转基因和基因敲除斑马鱼模型,以及研发用于斑马鱼模型的遗传操作方法。4) 筛选调控血管内皮细胞和运动神经元行为的天然化合物。