温度驯化对尖头热耐受特征的影响

俞 丹沈中源,张 智,张 晨,唐琼英刘焕章

(1. 中国科学院水生生物研究所, 水生生物多样性与保护重点实验室, 武汉 430072; 2. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049)

俞 丹1沈中源1,2张 智1,2张 晨1,2唐琼英1刘焕章1

(1. 中国科学院水生生物研究所, 水生生物多样性与保护重点实验室, 武汉 430072; 2. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049)

为了研究不同驯化温度对尖头(Rhynchocypris oxycephalus)热耐受特征的影响, 本研究设置4组水温(14℃、19℃、24℃和29℃), 对尖头驯化两周, 采用临界温度法观察尖头的耐受温度。结果显示: 尖头的热耐受性受到温度驯化的影响, 表现为高温驯化可以升高最大临界温度(CTmax), 4个驯化组的平均CTmax分别为32.29℃、33.23℃、33.40℃和35.71℃; 低温驯化可以降低最小临界温度(CTmin), 平均CTmin分别为0.00、0.10℃、2.10℃和5.27℃; 在适中的温度(19℃)驯化条件下具有最高的温度耐受范围(33.13℃)。在高温条件下的温度驯化具有较高的驯化反应率, 最大值出现在24—29℃内(0.46); 低温驯化反应率最大值出现在29—24℃内, 为0.63。尖头在本研究的驯化区间(14—29℃)内的热耐受区域面积为478.98℃2, 与温水性鱼类的温度耐受性相当, 说明尖头具有较强的温度适应能力。

尖头; 热耐受; 驯化温度

温度是影响生物各项生命活动的重要环境因子[1,2]。生物对环境温度变化具有一定的耐受范围。鱼类属于变温动物, 其生命活动严格受其栖息水环境的限制, 如果水温超过了鱼类的耐受范围,鱼类很可能会死亡。目前, 全球气候变化的一个趋势是全球变暖, 气候变暖将导致河流、湖泊和海洋温度升高, 这势必将对鱼类的分布、形态、生理和行为等产生重大影响[3]。因此, 对鱼类进行热耐受特征研究具有重要意义。大量的研究表明温度驯化可以改变鱼类的热耐受性特征[4—6]。对北美116种淡水鱼类的热耐受研究综述发现, 其临界温度或初始致死温度与驯化温度均成显著线性相关[7]。目前, 国内淡水鱼类的热耐受特征研究仍较为少见,已经开展了南方鲇(Silurus meridionalis)、点篮子鱼(Siganus guttatus)等部分鱼类的热耐受研究[8,9]。鱼类的热耐受特征研究对于鱼类的生态与分布具有重要意义, 也可以为物种保护措施的制定提供科学指导, 因此, 需要对更多鱼类进行热耐受性和温度适应性的研究[10,11]。近年来, 对鱼类的热耐受性特征研究普遍采用临界温度法 (Critical thermal methodology, CTM)。比起传统的突变转移法获得的起始致死温度 (Incipient Lethal Temperature technique, ILT), CTM法具有实验鱼用量少, 无需致死实验鱼, 操作方便等优点[7,11,12]。

1 材料与方法

1.1 实验鱼的来源与驯化

1.2 实验方案

1.3 数据处理

临界温度(CTmax和CTmin)为10尾实验鱼失去平衡时各监测温度的平均值。

驯化反应率(Acclimation response ratio, ARR)计算公式如下: ARR=ΔCTm/ΔTm。

ΔCTm是指不同驯化温度条件下的临界温度ΔCTmax和ΔCTmin平均值的差值, ΔTm即不同驯化温度之间的差值。高温驯化反应率=ΔCTmax/ΔTm, 低温驯化反应率=ΔCTmin/ΔTm。

热耐受区域(Thermal tolerance polygon)面积是指不同驯化温度下由CTmax和CTmin所绘出的多边形面积[15]。

在SPSS 19.0中采用单因素方差分析(ANOVA)统计温度处理对CTmax和CTmin的影响, 采用DUNCAN多重比较CTmax和CTmin有差异驯化组, 显著性水平P<0.05。在Excel 2013中绘制热耐受区域面积。

2 结果

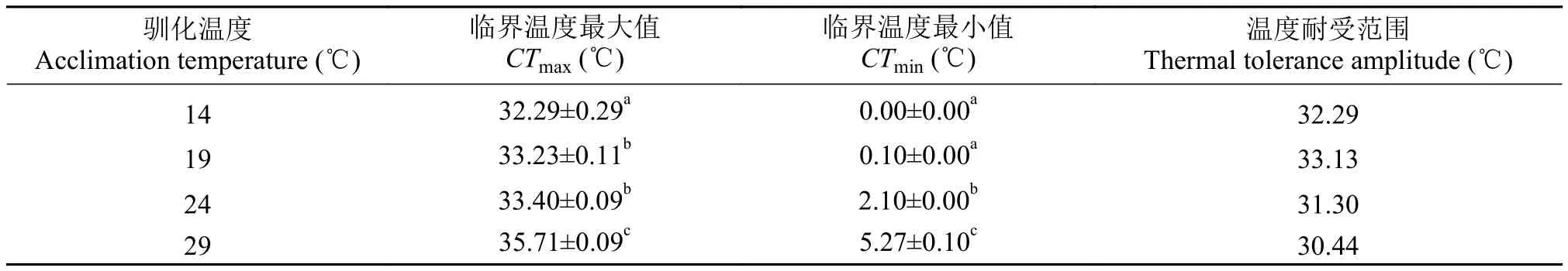

各驯化温度下(14℃、19℃、24℃和29℃)的最大临界温度(CTmax)和最小临界温度(CTmin)分别为32.29℃、33.23℃、33.40℃、35.71℃和0.00、0.10℃、2.10℃、5.27℃(表 1, ANOVA, P<0.05)。由此可见, 尖头的最大临界温度会随着驯化温度的升高而升高, 最小临界温度会随着驯化温度的降低而降低。

14—19℃、19—24℃和24—29℃区间内对应的ΔTmax值分别为0.94℃、0.17℃和2.31℃, ΔTmin值分别为0.10℃、2.00℃和3.17℃。因此, 尖头的高温耐受驯化反应率为0.19 (14—19℃)、0.03 (19—24℃)、0.46 (24—29℃), 低温耐受驯化反应率为0.63 (29—24℃)、0.40 (24—19℃)、0.02 (19—14℃)(表 2)。驯化反应率与驯化温度的关系为CTmax(y=0.21x+29, R2=0.8590)和CTmin(y=0.36x–5,R2=0.8694), 高温和低温的驯化率最大值均出现在24—29℃内。

表 1 尖头在不同驯化温度条件下的热耐受范围Tab. 1 Thermal tolerance of R. oxycephalus at different acclimation temperatures

表 1 尖头在不同驯化温度条件下的热耐受范围Tab. 1 Thermal tolerance of R. oxycephalus at different acclimation temperatures

注: 数据为平均值±标准误, 同一列数据上标英文字母不同表示存在显著差异(ANOVA, P<0.05)Note: Data are presented by Mean±SE. Values with different superscript letters within a column indicates significant difference (ANOVA, P<0.05)

温度耐受范围Thermal tolerance amplitude (℃) 14 32.29±0.29a0.00±0.00a32.29 19 33.23±0.11b0.10±0.00a33.13 24 33.40±0.09b2.10±0.00b31.30 29 35.71±0.09c5.27±0.10c30.44驯化温度Acclimation temperature (℃)临界温度最大值CTmax(℃)临界温度最小值CTmin(℃)

表 2 尖头不同驯化温度条件下的驯化反应率Tab. 2 Acclimation response ratios of R. oxycephalus at different acclimation temperatures

参数Parameter驯化温度范围Acclimation temperature range (℃)驯化温度差值ΔT (℃)临界温度差值ΔCTm(℃)驯化反应率Acclimation response ratio CTmax 14—19 5 0.94 0.19 19—24 5 0.17 0.03 24—29 5 2.31 0.46平均值 15 3.42 0.23 CTmin 29—24 5 0.10 0.63 24—19 5 2.00 0.40 19—14 5 3.17 0.02平均值 15 5.27 0.35

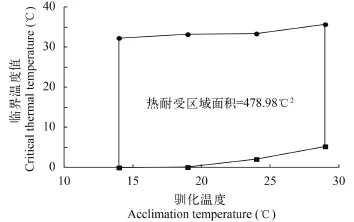

在各驯化温度(14℃、19℃、24℃和29℃)条件下, 尖头的温度耐受范围(CTmax–CTmin)分别为32.29℃、33.13℃、31.30℃和30.44℃(表 1)。其中最大温度耐受范围为33.13℃, 出现在19℃驯化条件下, 对应的临界温度最大值和最小值分别为33.23℃和0.1℃。在14—29℃区间内, 尖头的热耐受区域面积为478.98℃2(图 1)。

3 讨论

图 1 尖头的热耐受区域面积Fig. 1 Thermal tolerance polygon of R. oxycephalus

鱼类的温度耐受范围是指鱼类可以耐受的高温上限和低温下限之间的范围, 它是评价鱼类热耐受特征的重要指标。在未来全球气候变暖的情况下, 水温升高会造成鱼类的死亡率和分布范围发生改变[3]。根据鱼类对不同水温的适应情况, 通常将鱼类划分为3类: 冷水性鱼类、温水性鱼类和暖水性鱼类。通过比较不同环境温度条件下鱼类的温度耐受范围, 发现温水性鱼类的温度耐受范围一般比冷水性鱼类和暖水性鱼类大。例如, 冷水性鱼类虹鳟(Oncorhynchus mykiss)的最大温度耐受范围为28.9℃, 其对应的CTmax和CTmin分别为29.1℃和0.2℃[16]; 温水性鱼类南方鲇的最大温度耐受范围可达33.3℃, 对应的CTmax和CTmin分别为38.2℃和5.9℃[8]; 暖水性鱼类南亚野鲮(Labeo rohita)的最大温度耐受范围仅为27.4℃, 其对应的CTmax和CTmin分别为41.6℃和14.2℃[17]。在本研究中尖头的最大温度耐受范围出现在19℃驯化条件下, 其值为33.1℃, 对应的CTmax和CTmin分别为33.2℃和0.1℃。由此可见, 尖头与温水性鱼类的最大温度耐受范围最为相近, 但最大、最小临界温度均小于温水性鱼类。尖头的最大温度耐受范围出现在一个适中的温度驯化条件下(19℃), 与其他鱼类的热耐受研究结论一致[7]。因为在较低的驯化温度下, 鱼类容易具有较低的低温耐受值, 但相应的高温耐受值偏低, 反之, 在较高的驯化温度下, 鱼类容易具有较高的高温耐受值, 但相应的低温耐受值偏高, 所在适中的驯化温度下, 鱼类反而可以获得更大的温度耐受范围。

除温度耐受范围以外, 热耐受区域面积是评价鱼类热耐受特征的另一个重要指标, 是指不同驯化温度下由CTmax和CTmin所绘出的多边形面积, 单位为℃2。通常来说, 温水性鱼类的热耐受区域面积比冷水性鱼类和暖水性鱼类的大。例如, 暖水性鱼类南亚野鲮在14—29℃驯化条件下的热耐受区域面积约为399.80℃2, 温水性鱼类南方鲇在相同条件下的热耐受区域面积约为470.89℃2。在本研究中尖头在14—29℃的热耐受区域面积为478.98℃2,与温水性鱼类南方鲇的热耐受区域面积相近。由此可见, 虽然尖头分布的自然栖息环境属于山区冷水性溪流, 但是在实验室条件下, 它依然具有与温水性鱼类相当的温度耐受范围和热耐受区域面积, 这说明尖头具有较强的温度适应能力。在未来气候变暖的情况下, 较强的温度适应能力有助于尖头的生存与扩散。

驯化反应率(ARR)是指单位驯化温度(升高或降低1℃)对鱼类临界温度(CT)作用的效率, 也是评价鱼类对温度变化生理反应的常用指标, 反映了鱼类对驯化温度敏感程度的大小。驯化反应率越大,表明驯化过程对鱼类耐受温度范围的影响作用就越大。在绝大多数驯化温度条件下, 低温驯化反应率均大于高温驯化反应率, 在驯化温度20—30℃条件下, 暖水性鱼类大口黑鲈(Micropterus salmoides)的高、低温驯化反应率分别为0.32和0.76[16]; 温水性鱼类南方鲇在相同驯化温度下的高、低温驯化反应率分别为0.12和0.39[8]; 冷水性鱼类虹鳟在驯化温度10—20℃条件下的驯化反应率分别为0.18和0.36[16]。在14—29℃驯化条件下, 尖头的高、低温驯化反应率分别为0.23和0.35, 该结果与上述研究的结论基本一致, 较高的低温驯化反应率表明尖头对低温驯化较为敏感, 暗示尖头对低温环境可能有较强的适应能力。在24—29℃区间内, 尖头的高温驯化反应率为0.46, 是高温驯化反应率中的最大值; 在29—24℃时的低温驯化反应率为0.63,也是低温驯化反应率中的最大值, 表 3中的数据表明尖头在这两个区间内的驯化反应率明显大于其他区间, 表明温度驯化对尖头的热耐受性影响程度存在不同。因此, 一定温度范围内的驯化可以提高尖头的温度适应性。

致谢:

感谢周卓诚在采样过程中给予的帮助, 感谢王剑伟、张伟伟、罗思在实验设备上提供的帮助。

[1]Fry F E J. Effects of the environment on animal activity [J]. University of Toronto Studies, Biological Series No. 55, Publications of Ontario Fisheries Research Laboratory, 1947, 68: 1—62

[2]Willmer P J, Stone G N, Johnston I A. Environmental Physiology of Animals [M]. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. 2000

[3]Roessig J M, Woodley C M, Cech J J, et al. Effects of global climate change on marine and estuarine fishes and fisheries [J]. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 2004, 14(2): 251—275

[4]Heath W G. Thermoperiodism in sea-run cutthroattrout (salmo clarki clarki) [J]. Science, 1963, 142(3591): 486—488

[5]Kowalski K T, Schubauer J P, Scott C L, et al. Interspecific and seasonal differences in the temperature tolerance of stream fish [J]. Journal of Thermal Biology, 1978, 3(3): 105—108

[6]Shafland P L, Pestrak J P. Lower lethal temperatures for fourteen non-native fishes in Florida [J]. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 1982, 7(2): 149—156

[7]Beitinger T L, Bennett W A, McCauley R W. Temperature tolerances of North American freshwater fishes exposed to dynamic changes in temperature [J]. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 2000, 58(3): 237—275

[8]Wang Y S, Cao Z D, Fu S J, et al. Thermal tolerance of juvenile Silurus Meridionalis Chen [J]. Chinese Journal of Ecology, 2008, 27(12): 2136—2140 [王云松, 曹振东, 付世建, 等. 南方鲇幼鱼的热耐受特征. 生态学杂志, 2008, 27(12): 2136—2140]

[9]Wang Y, Song Z M, Liu J Y, et al. Thermal tolerance of juvenile Siganus Guttatas [J]. Marine Fisheries, 2015, 37(3): 253—258 [王妤, 宋志明, 刘鉴毅, 等. 点篮子鱼幼鱼的热耐受特征. 海洋渔业, 2015, 37(3): 253—258]

[10]Cook A M, Duston J, Bradford R G. Thermal tolerance of a northern population of striped bass Morone saxatilis [J]. Journal of Fish Biology, 2006, 69(5): 1482—1490

[11]Eme J, Bennett W A. Critical thermal tolerance polygons of tropical marine fishes from Sulawesi, Indonesia [J]. Journal of Thermal Biology, 2009, 34(5): 220—225

[12]Cowles R B, Bogert C M. A preliminary study of the thermal requirements of desert reptiles [J]. Bulletin of The American Museum of Natural History, 1944, 83: 261—296

[13]Chen Y Y. Fauna Sinica, Osteichthyes, CypriniformesⅡ[M]. Beijing: Science Press. 1998, 86—87 [陈宜瑜.《中国动物志-硬骨鱼纲鲤形目》中卷, 北京: 科学出版社. 1998, 86—87]

[14]Yu D, Chen M, Zhou Z C, et al. Global climate changewill severely decrease potential distribution of the East Asian coldwater fish Rhynchocypris oxycephalus (Actinopterygii, Cyprinidae) [J]. Hydrobiologia, 2012, 700(1): 23—32

[15]Dalvi R S, Pal A K, Tiwari L R, et al. Thermal tolerance and oxygen consumption rates of the catfish Horabagrus brachysoma (Günther) acclimated to different temperatures [J]. Aquaculture, 2009, 295(1—2): 116—119

[16]Currie R J, Bennetf W A, Beitinger T L. Critical thermal minima and maxima of three freshwater game—fish species acclimated to constant temperatures [J]. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 1998, 51(2): 187—200

[17]Chatterjee N, Pal A K, Manush S M, et al. Thermal tolerance and oxygen consumption of Labeo rohita and Cyprinus carpio early fingerlings acclimated to three different temperatures [J]. Journal of Thermal Biology, 2004, 29(6): 265—270

[18]Rajaguru S. Critical thermal maximum of seven estuarine fishes [J]. Journal of Thermal Biology, 2002, 27(2): 125—128

[19]Bevelhimer M, Bennett W. Assessing cumulative thermal stress in fish during chronic intermittent exposure to high temperatures [J]. Environmental Science & Policy, 2000, 3: S211—S216

[20]Baker S C, Heidinger R C. Upper lethal temperature of fingerling black crappie [J]. Journal of Fish Biology, 1996, 48(6): 1123—1129

EFFECT OF TEMPERATURE ACCLIMATION ON THE THERMAL TOLERANCE OF RHYNCHOCYPRIS OXYCEPHALUS

YU Dan1, SHEN Zhong-Yuan1,2, ZHANG Zhi1,2, ZHANG Chen1,2, TANG Qiong-Ying1and LIU Huan-Zhang1

(1. The Key Laboratory of Aquatic Biodiversity and Conservation of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430072, China; 2. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China)

Temperature is one of the most important environmental factors that impact the physiological activities of fishes. Fishes exhibit thermal tolerance, which are influenced by temperature acclimation. Global climate change is one potential factor affect the survival and growth of fish species. Therefore, investigation of thermal tolerance of various fish species is of great importance. Rhynchocypris oxycephalus is a typical cold-water fish that might be influenced by the future global warming. The current study investigated thermal tolerance of R. oxycephalus using critical thermal methodology by acclimating the fish to 14, 19, 24 and 29℃ temperature for two weeks. The results showed that thermal tolerance of R. oxycephalus regulated by temperature acclimation, and that the critical thermal maxima (CTmax) increased with the increase of temperature acclimation, and that the average CTmaxwere 32.29, 33.23, 33.40 and 35.71℃. The critical thermal minima (CTmin) decreased with the decrease of temperature acclimation, and the average CTminwere 0.00, 0.10, 2.10 and 5.27℃. At the moderate acclimation temperature (19℃), R. oxycephalus has the widest thermal tolerance up to 33.13℃. The higher acclimation temperatures produced higher acclimation response ratio (ARR). The maximum ARR (0.46) of high temperatures occurred in the range of 24—29℃, while the maximum ARR of low temperatures, (0.63) occurred in 29—24℃. A thermal tolerance polygon in the range of 14 to 29℃ showed an area of 478.98℃2, which was similar with eurythermal fishes. These results indicated that R. oxycephalus has strong ability for thermal adaption.

Rhynchocypris oxycephalus; Thermal tolerance; Temperature acclimation

Q178.1

A

1000-3207(2017)03-0538-05

10.7541/2017.69

2016-04-18;

2016-07-11

国家自然科学基金(31401968和31272306)资助 [Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31401968, 31272306)]

俞丹(1985—), 女, 浙江嵊州人; 博士; 主要从事鱼类分子进化研究。E-mail: yudan@ihb.ac.cn

刘焕章, E-mail: hzliu@ihb.ac.cn