熊、布尔什维克、粗人、间谍

By+Meagan+Day

Donald Trump is comfortable with Vladimir Putin—too comfortable, it seems, for American tastes.

On the one hand, objections to his admiration for the Russian leader are understandable. Putins authoritarian tendencies are well-documented, and its incumbent on any leader to at least act appalled by his hunger for annexation and repression of dissent.2

But when Americans react with horror to Trumps Putinfriendliness, theres something else going on, too. Americans are really, really freaked out3 by Russia. The Cold War is over, but Russophobia is still branded on the American psyche.4

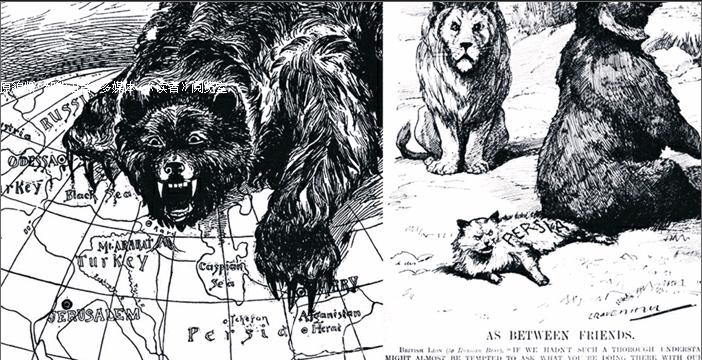

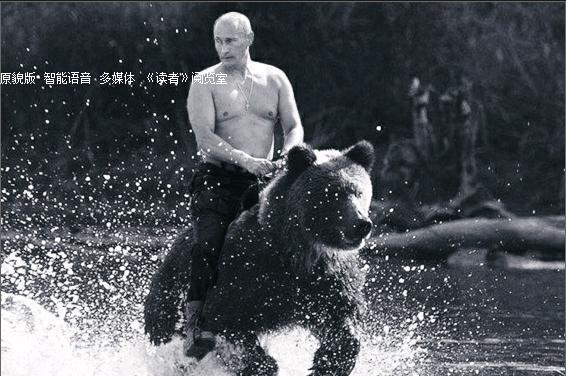

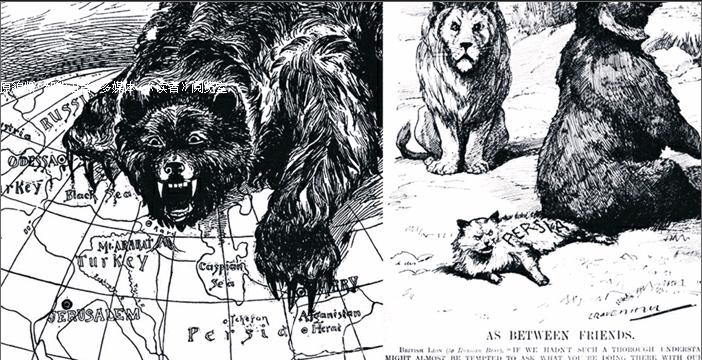

Even before the Cold War, Russia never really rubbed America the right way.5 The favored representation of Russia in 19th century political cartoons was the bear. Sometimes the bear was portrayed as a clumsy oaf who doesnt know his own strength; other times, the bear was a menacing predator.6 These two tropes7 continued to characterize American representations of Russia throughout the 20th century, and still do today.

But when the Tsar was overthrown in 1917 and the Soviet Union was established a few years later, American fear of the Russians began to manifest in human form: namely, the Bolshevik agitator.8 Paranoia about Russian communists gripped the nation in what came to be known as the First Red Scare.9 In 1919 alone, anti-communist films included Bullin the Bullsheviki, Bolshevism on Trial and The Red Viper. That same year, U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer ordered the arrest of more than 4,000 alleged10 communists, many of them Russian immigrants.

In the following years, a spate of films depicted in detail the horrors of Russian communism.11 Russians in the American imagination were either poor victims of Bolshevism abroad, or they were diabolical extremists intent on consolidating power and obliterating freedom and prosperity in America.12 The term “Russian reds”was as popular as “Islamic extremists” is now, and inspired a similar sense of revulsion13 and dread for many Americans.

As intense as the First Red Scare was, it was brief and small-scale compared to the Second Red Scare14, at the height of the Cold War. After World War II, the USSR had emerged as a formidable world power and adversary of the United States, strong enough to develop atomic weaponry,15 spy on Americans, and race to outer space.

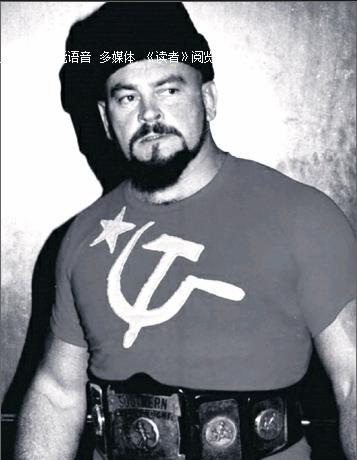

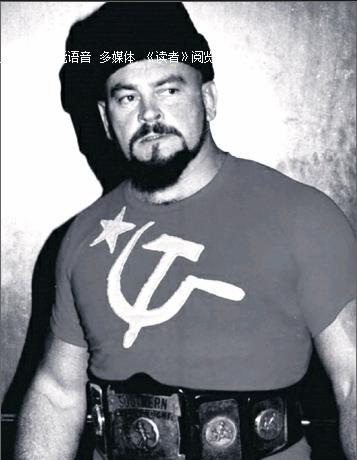

Popular American culture throughout the mid-20th century portrayed Russians as sneaky16 and menacing. In the McCarthyist era—a time when even faint or alleged sympathies with communism could get you blacklisted for life, and convicted Russian spies were executed on American soil—Russia was synonymous with scheming, secrecy, espionage and intrigue.17 Cold War spy films produced a new round of Russian stock characters and stereotypes: the devious and clever double-agent, the unsmiling KGB officer, the sadistic mob boss, the lethal seductress, and so on.18

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the pendulum swung again from menacing to inept.19 As Russia began to emerge as a capitalist nation, it struggled to find its footing—and America laughed. Starting in the 1990s, a new group of Russian stereotypes emerged, including the heavy-drinking, hot-tempered Eastern cowboy (think the Russian astronaut in Armageddon bashing machinery with a wrench, exclaiming, “This is how we fix problems in the Russian space station!”), and the garish, tacky and eccentric Russian nouveau-riche.20 But Russian villainy never faded from view, even if it increasingly served as a punchline.21 In The New York Times, Steven Kurutz points out that action movie antagonists22 became more diverse in the final years of the Cold War, but seem to have actually become more uniformly Russian again in recent years.

The truth is, Americans are still uneasy with Russia; the stereotypes persist, and the mistrust lingers23. A century of mutual animosity24 still sticks in the average Americans imagination. And geopolitical alliances change quicker and with more facility than the hearts and minds of the populace.25 So, through various ups and downs in U.S.-Russia relations, American citizens have remained leery26 of Russians.

Trumps reverence for Putin is unbecoming, given Trumps own inclination toward authoritarianism—but thats not the only reason Americans are bristling.27 We have a special attachment to Russians, a special fixation28 on their shortcomings ranging from aggression to incompetence. For Americans today, Russia is still the bear.

唐纳德·特朗普和弗拉基米尔·普京处得颇好,也许,对于美国人来说,好得过了头。

一方面来说,美国人反感他对这位俄罗斯领导的赞赏是可以理解的。普京的独裁倾向显而易见,任何一位国家领导人至少应该对他的吞并野心和压迫异见者的行径表现出恐惧。

美国人对特朗普的“亲京”感到恐惧,还有其他一些原因。美国人真的特别害怕俄罗斯。尽管冷战早已结束,但美国人的头脑里早已烙下深深的“恐俄症”。

即便在冷战之前,俄罗斯也从不曾讨好过美国。19世纪时,最受欢迎的代表俄罗斯形象的政治漫画是一只熊。有时候这只熊被画成笨头笨脑的呆子,缺乏自知之明;有时候它又是险恶的猎食者。这两个形象代表了20世纪美国人对俄罗斯的印象,直至今天。

1917年俄国沙皇被推翻,几年后苏联成立,美国人对俄罗斯的恐惧开始有了具体的人形对象:鼓吹布尔什维克的人。对俄国共产主义者的猜疑笼罩整个美国,也就是所谓的“第一次红色恐慌”。仅在1919年,反共主题的电影就有《肃清布尔什维克》、《布尔什维克的审判》和《红蝰蛇》。同年,美国总检察长亚历山大·米切尔·帕尔默下令逮捕四千多名所谓的的共产主义者,大部分是俄罗斯移民。

接下来那几年涌现了一系列详细描述俄共产主义恐慌的电影。在美国人的想象中,俄罗斯人要不就是海外那些可怜的布尔什维克的受害者,要不就是可恶的极端主义分子,企图巩固强权以消灭美国的自由和繁荣。“赤色俄罗斯”一词如同当下的“伊斯兰极端分子”一般,引起很多美国人的厌恶和恐惧。

尽管“第一次红色恐慌”的局势如此緊张,但相比冷战高潮期的“第二次红色恐慌”,其持续时间短,规模也较小。第二次世界大战之后,苏联成为世界一大霸主,与美国实力抗衡,强大到发展核武器、派间谍暗中监视美国和展开太空探索。

20世纪中期,美国的主流文化把俄罗斯人塑造成鬼祟、险恶的形象。在麦卡锡时代,只要你稍微或者疑似同情共产主义,都可能被列入终身黑名单,被定罪的俄罗斯间谍在美国领土上被处决——俄罗斯就是阴谋、秘密、间谍和密谋的同义词。冷战间谍片产生了新一波关于俄罗斯的固定角色和刻板印象:鬼祟狡猾的双面间谍、不苟言笑的克格勃官员、残忍至极的犯罪团伙首领、致命诱惑的美女等等。

苏联解体之后,美国人对俄罗斯人的印象从险恶再次变成愚蠢。俄罗斯逐渐发展为资本主义国家,挣扎着寻找自己的立足点——这让美国嘲笑不已。从20世纪90年代开始,一波新的关于俄罗斯的刻板形象开始出现,包括嗜酒如命、脾气暴躁的东部牛仔(电影《绝世天劫》中的俄罗斯宇航员拿扳手用力敲打机器,大声喊着:“在俄罗斯太空站我们就是这么修理东西的!”),或是衣着花哨、趣味低俗、性格古怪的俄罗斯暴发户。但是在美国人眼中,俄罗斯人的罪行从未消失过,即便它只是越来越多地被当成笑话中的“梗”而已。史蒂文·库鲁兹在《纽约时报》上指出,冷战最后那几年,动作片中的反派人物变得多样化,但近几年貌似又再次通通变回俄罗斯人的形象。

事实上,美国人还是对俄罗斯很不放心;那些刻板印象和不信任感依旧存在。彼此之间持续一个世纪的敌意在普通美国民众心目中仍然难以消除。如今的地缘政治联盟说变就变,相比之下,普通民众的心理却无法轻易改变。在美俄关系的起起落落中,美国公民对俄罗斯依然保持着警惕的态度。

鉴于特朗普本人的独裁主义倾向,他对普京的敬重是不适宜的——但这恐怕不是令美国人感到恐惧的唯一原因。我们对俄罗斯人有一种特殊的感情,对于他们的缺点有特别的固恋,从他们的攻击性到他们的无能。对于今天的美国人来说,俄罗斯依旧是那头熊。

1. Bolshevik: 布尔什维克(20世纪初拥护列宁及其政治观点的人);buffoon:粗俗而愚蠢的人。

2. authoritarian: 独裁主义的,权力主义的;incumbent: 有责任的,义不容辞的;appall: 惊吓,使……恐惧;annexation: 吞并,强行占领;repression: 压制,镇压;dissent: 分歧,异议。

3. freak out: 吓坏,使……害怕。

4. Cold War: 冷战,指1946年至1991年之间,以美国、北大西洋公约组织为主的资本主义阵营与以苏联、华沙条约组织为主的社会主义阵营之间的政治、经济、军事斗争;Russophobia:由Russia和phobia(恐惧,厌恶)两个单词合成;brand: v. 给……打上烙印;psyche: 灵魂,精神。

5. rub sb. the right way: 讨好某人,让某人高兴。

6. clumsy: 笨拙的;oaf: 傻瓜,痴儿;menacing: 险恶的;predator:捕食者,食肉动物。

7. trope: 转义,比喻。

8. Tsar: 俄国沙皇;Soviet Union: 苏联,全称“苏维埃社会主义共和国联盟”(USSR),1922年12月30日由俄罗斯、白俄罗斯、乌克兰、外高加索合并组成的社会主义联邦制国家,于1991年12月25日解体;manifest: 显示;agitator:(尤指政治变革的)鼓动者,煽动者。

9. paranoia: 臆想,凭空猜疑;grip: 影响,控制;First Red Scare: 第一次红色恐慌,自1917年俄国十月革命爆发后延续至1920年,指在美国兴起的反共产主义风潮。

10. alleged: (未经证实而)被指控的。

11. a spate of: 一系列的,大量的;depict: 描述,描绘。

12. diabolical: 恶魔的,残忍的;obliterate: 消灭,摧毁。

13. revulsion: 厌恶,强烈反感。

14. Second Red Scare: 第二次红色恐慌,指始于1947年,并几乎贯穿20世纪50年代的麦卡锡主义后遗症,恐慌来自于美国国内外共产主义者对美国社会的影响以及对联邦政府的间谍行为,导致美国政府制定了形形色色的反共政策。

15. formidable: 强大的,令人生畏的;adversary: 对手,强手;atomic: 原子能的。

16. sneaky: 鬼祟的,暗中的。

17. McCarthyist era: 麦卡锡时代(1950—1954),指肇因于美国参议员麦卡锡的恶意诽谤、肆意迫害疑似共产党和民主进步人士的时期,是美国历史上最黑暗的时期之一;synonymous: 同义的;scheming:密谋,策划;espionage: 间谍活动;intrigue: 阴谋,密谋。

18. stock character: 传统角色,固定角色;devious: 不正大光明的,狡猾的;KGB:〈俄〉克格勃(苏联国家安全委员会);sadistic: 虐待狂的;mob: 犯罪团伙;lethal: 致命的;seductress: 勾引男人的女子。

19. pendulum: 摇摆不定的事态或局面;inept: 无能的,愚蠢的。

20. Armageddon:《绝世天劫》,是1998年出品的一部科幻灾难电影;bash:猛击;wrench: 扳手;garish: 花哨的,过分艳丽的;tacky: 俗气的,低级趣味的;nouveau-riche:〈法〉暴发户。

21. villainy: 凶恶,罪行;punchline:(故事、笑话中的)妙语,点睛之笔。

22. antagonist: 对手,敌人。

23. linger: 逗留,徘徊。

24. animosity: 憎恨,敵意。

25. geopolitical: 地缘政治的,即根据地理要素和政治格局的地域形式,分析和预测世界或地区范围的战略形势和有关国家的政治行为;with facility: 容易地,不费力地;populace:平民百姓。

26. leery: 警惕的,怀有戒心的。

27. reverence: 尊敬,敬畏;unbecoming:不相称的,不适宜的;authoritarianism:独裁主义;bristle:(因害怕、激怒等而)毛发直立。

28. fixation: 固恋,偏爱。