Elements of a Design Strategy 设计策略的要素

文/卡里•约尔马卡 By Kari Jormakka

Elements of a Design Strategy 设计策略的要素

文/卡里•约尔马卡 By Kari Jormakka

除了提出将世界从装饰中解放外,阿道夫•路斯(Adolf Loos)的“空间体量设计”理念还掀起了建筑领域的哥白尼式革命。他曾说:“人类过去无法进行空间思维,建筑师不得不把浴室设计得和客厅一样高”,但“人类终将学会玩三维棋盘,所以未来的建筑师同样也将解决三维建筑设计问题。”

但到目前为止,似乎多数人都没能达到路斯的预期。斐迪南•马克(Ferdinand Maack)于1907年发明了德国式空间国际象棋,但其从未得到普及,如今,人们多是通过《星际迷航》系列电影才知道三维国际象棋的。然而幸运的是,仍然有建筑师实现了路斯预言的后半部分,德鲁甘-麦斯尔联合建筑师事务所即是为数不多的“三维棋盘”建筑大师之一,相比平面,它的设计更注重剖面效果。

DMAA近期设计完成的苏格兰敦提市维多利亚和阿尔伯特博物馆即是这种设计理念的突出例证。该博物馆位于敦提市滨海区,占地面积极小,犹如巨大的冰川漂砾,长达40米的悬臂甚至超出了建筑大师奥斯卡•尼迈耶(Oscar Niemeyer)最狂野的想象。但是,其地面并非天然的,同样也是建造出来的。德鲁甘-麦斯尔将公共广场延伸至了泰伊河河口,同时将其合拢,提供了进入悬于其上主楼的入口。因此,公共广场垂直向内翻转进入建筑,所有功能区域围绕这个“公共空间”分组布置。

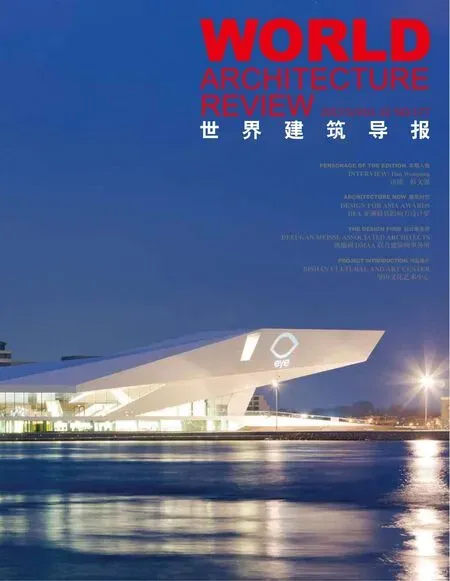

类似的剖面理念同样为阿姆斯特丹电影博物馆增添了生气和活力。博物馆泊靠于艾河北岸,从城市中央火车站跨水而建,水晶般的光芒使伫立其旁的欧法赫斯塔黯然失色。博物馆内部,四个放映厅、一个研究中心、一个图书馆、一间餐厅、一间商店和多个工作空间围合成一个大型火山口式中庭,或者说更像一个竞技场,为城市生活的演绎提供了各色舞台。

景观

从外部看,这些大型建筑就像抽象雕塑,内部通过广阔视角、倾斜平面、大量楼梯和阔景阳台开辟出人工景观。的确,建筑根据景观模型塑形是DMAA作品中反复出现的主题,无论是维也纳Wimbergergasse的办公大楼还是公寓建筑,亦或经过精心打造的萨尔斯堡上行观光电梯都是如此。尽管没有大型项目摄人心魄的悬臂、Ray1的钢质健身房或RT私人住宅的人工景观,电梯与陡壁完美地融为一体,成为了其不可分割的一部分。

DMAA室内装饰的效果不仅仅依赖于动力地形的形式美学。对地面基准的重新定义是一种更为强大的表现手法,相比其他形式处理,其能更直接地吸引观者。由于我们往往或多或少地局限于水平面设计,因此,我们能敏锐的察觉到建筑体的垂直位置。同时,德鲁甘-麦斯尔似乎还采用了英国人文地理学家杰・阿普拉顿(Jay Appleton)的“瞭望”和“藏匿”景观美学原理。在伯克崇高理论和达尔文进化论的基础上,阿普拉顿提出,看见和隐蔽的能力,即“瞭望”和“藏匿”对生物体在人类和次人类层面的生存前景都非常重要。他进一步提出了四种不同的视野,即全景广角视野、远景框架视野以及全景和远景的间接视野,例如从塔楼看到的二次全景,或从篱笆缝隙获得的偏转或偏置远景。同样,“藏匿”也可以有很多形式。

从私人住宅和公寓到大型公共建筑,DMAA的所有作品无不体现了“藏匿”和“瞭望”的相互作用,一种景色小巧、隐蔽,另一种景色则广阔而明亮。除了形式体系,德鲁甘-麦斯尔还倾向于将建筑视作行为的舞台。尤其是进入、穿过和观察建筑的意境都经过精心排布,通过驻足凝望将各个空间联系起来。

展演

展演性对DMAA的作品至关重要。建筑设计并非源于场地、项目或地形分析,而更多受到背景、活动和建筑类型的影响,这点在公共建筑中尤为明显。在搭建前,我们甚至不知道DMAA建筑的功能是什么,因为建筑学干预影响着文化感知和社会传统。同时,建筑外形也加强了建筑的展演性。除了美观外,复杂的折叠几何形状与罗伯特•莫里斯和其他上世纪六十年代极简抽象派艺术家的雕塑作用类似,即通过外形的不断转换,引导观者从不同角度对建筑进行探索。

对于极简抽象雕塑早期批评家迈克尔•弗雷德(Michael Fried)来说,作品和观者的相互依赖性实际上牺牲了艺术的纯粹性。他认为,极简抽象作品实际上是拟人化、对抗性和“戏剧性”的,因为它影响了观者的身体尺度,同时需要观者去完善作品所表达的关系网。尽管如此,如果我们将这种观点应用在建筑中,很快我们就会明白,弗雷德关于极简抽象主义的批判,包括观者与作品融合、作品体验的时间展开及尺度的身体感知和理解正是建筑,尤其是DMAA作品的内涵所在。

生理学

与试图以额外建筑理论为基础的现代建筑实践不同,DMAA的作品善用文字手法,与描述和外形截然不同。这种手法的力量源自人类身体和建筑背景的饼子,形式的意义体现在其产生的活动中。在某种程度上,德鲁甘-麦斯尔走近了尼采所许诺的生理美学。

尽管许多DMAA项目的外观引人入胜,但其并不仅仅是迎合视觉感受,而更多地是对运动物体速度的组织。在空间体验中,重要的是人体成为可能性行为的系统,正如莫里斯•梅洛-庞蒂(Maurice Merleau-Ponty)所说,“我的身体即有待作出行为的所在。”这也是为什么不能撇开人体、功能和时间去思考空间的原因。

维也纳威滕伯格(Wienerberg )的城市LOFT项目(2004)即是生理手法的一个简单示例。建筑外立面体现了将建筑外表作为独立元素的情致,同时,也表现出了对现代装饰的巧妙探索。建筑剖面依然是欣赏建筑最重要元素的最佳手段。与2.5m相同层高的楼层反复叠加不同,建筑在南侧设计了3.4m高的居住区,而北侧更加私密的放松或休息区则采用了2.4m层高,从而将不同层高融于一体,让空间体量设计相互关联。公寓类型和空间条件的异常多样性来自这样一个极为简单的理念,即响应人体的功能性、生理性和结构性需求。

崇高

尽管DMAA可以说已经颠覆了弗雷德对戏剧性的批判,建筑和雕塑依然存在巨大差异,其中一个便是尺度。正如埃德蒙•伯克(Edmund Burke)在1757年提出的崇高理论中所称,大尺度开辟了全新的美学效应,尤其是崇高体验。大尺寸往往容易唤起崇高感,同时,伯克还认为,高度比长度和宽度更加有效,因为其更能与人体生理极限形成对比并让其主位化,而保时捷博物馆或达拉特国王阿卜杜拉二世文化和艺术馆中的巨大悬臂则以人们在自然界中前所未见的方式克服重力作用,当然也产生了最彻底的崇高效应。

除了将崇高体验称为思想能够感知的最强烈情绪外,伯克还解释道:“思想被其对象塞得太满,而无法容下任何其他事物,或被其所思事物的后果和原因所取悦。”尽管如此,崇高感并不能通过自身呈现。它是在人类思想面对超出界定之外的事物时所产生的。伯克和伊曼努尔康德(Immanuel Kant)认为,崇高不可分类,同时也不可确定,其产生于人们试图在有形事物中呈现不可见和无形事物时。这也是为什么追求崇高感的建筑必须抛弃具象、表象和指示性,同时排除记忆、联想、怀旧、传奇或神秘等其他障碍的原因。让-弗朗索瓦•利奥塔(Jean-Francois Lyotard)说,我们这一时代的精神无疑是“内在的崇高精神,涉及不可见的精神。”

外表

由于DMAA的作品与崇高效果大量相关,人们不应去寻找隐含意义,这是应当由批判家去挖掘和发现的秘密。建筑墙壁没有在其后藏匿任何事物,相反,墙壁本身即秘密。在保罗•瓦勒里(Paul Valéry)的解读中,我们可以指出,DMAA建筑作品的最深层次即建筑外表。

近年来,建筑越来越面临设计仅流于外表(具有或无媒体立面)的风险。DMAA的装饰物实验,如在Wimbergergasse或Paltramplatz的住房项目初看似乎与二维的类似情致背道而驰。尽管如此,对于他们来说,外皮中的真实建筑学理念与城市战略或总体建筑外形中体现的一样多,同时,外表是组织空间和社会关系的工具,而非仅仅是一个界定面或广告牌。

如果说雕塑是外部视觉观察的对象,则建筑不仅提供了外部美学特征,同时还提供了进入或拒绝进入建筑内部的阈值。打开或封闭建筑空间的外表通过过滤视觉、听觉、物理和其他连系,定义了开放性和隐私性程度。如同生物有机体,在DAMM的许多项目中,建筑外皮实际上并非二维表面,而更多地是定义其内部空间的一个器官。

DMAA的一个秘密就是在各个尺度和材料上运用相同原理和空间思维,同时关注各个元素的美观性和展演性的能力。

In addition to liberating the world from the burden of ornament, Adolf Loos boasted of having launched a Copernican revolution in architecture with his concept of the Raumplan. In the past, he claims, “mankind was unable to think in terms of space,and architects were compelled to make the bathroom as high as the salon,” but “as man will one day succeed in playing chess with a three-dimensional board, so other architects in the future will also solve the plan in three dimensions.”

So far, mankind at large seems to have failed Loos’ expectations. The Raumschach game, as introduced by Ferdinand Maack in 1907, never made it big, and today most people know three-dimensional chess only from old episodes of Star Trek.Fortunately, however, there are architects who have lived up to the second part of the Loosian prophecy. Delugan Meissl Associated Architects are among those few who really do play architecture on a three-dimensional board: their designs live from the section even more than the plan.

A striking demonstration is the recent design for the Victoria & Albert Museum in Dundee, Scotland. The building sits at the waterfront on an impossibly smallfootprint like a giant glacial erratic, with its 40-meter cantilevers outperforming even the wildest dreams of Oscar Niemeyer. But the ground is not a natural given either, but rather a construct. The architects extended the public plaza o ff shore into the River Tay estuary, and folded it so as to provide access to the main building hovering above it. Thus a public square turns vertical inside the building, with all the functions grouped around this ‘public void.’

Similar sectional concept animates the Film Museum in Amsterdam. Anchored on the north bank of the Ij, across the water from the city’s central train station, the building eclipses its tall neighbor, the Overhoeks Tower, with its crystalline brilliance.Inside, four screening rooms, a study center, a library, a restaurant, a shop and workspaces are grouped around a large crater-like atrium, or ‘arena’ that offers several stages for the performance of urban life.

Landscape

While from the outside these large buildings look like abstract sculptures, the interior opens up artificial landscapes with broad perspectives, tilted planes, massive staircases and wide balconies. Indeed, the shaping of the building according to a landscape model is a recurring theme in the work of DMAA, whether we think of their office and apartment building on the Wimbergergasse in Vienna or the unrealized panorama lift for Salzburg with its carefully orchestrated ascent to the top of the hill. Even without the death-defying cantilevers of the larger projects,or the steely gymnastics of House Ray I and the private house RT form artificiallandscapes, the latter one becoming literally part of the steep hill.

The effect of DMAA’s interiors does not only rely on the formal qualities of their dynamic topography. Rather, the redefinition of the ground datum is a powerfuldevice because it engages the viewer more directly than any other formalmanipulation. As we normally are limited to operating on a more or less horizontalplane, we are acutely aware of the vertical positioning of the body.

The architects also seem to make use of the principles that the British geographer Jay Appleton characterized as ‘prospect’ and ‘refuge’. Building upon Burke’s theory of the sublime and Darwin’s theory of evolution, Appleton suggested that the ability to see, a prospect, and the ability to hide, a refuge, are important in calculating a creature’s survival prospects at both human and sub-human level. He further articulated four di ff erent kinds of prospects: the wide view of a panorama vs. the framed view of a vista, and indirect versions of both, such as a secondary panorama from a tower or a de fl ected or o ff set vista from a break in a hedge. Analogously,the refuge can take many forms.

The interplay between refuge and prospect – one small and dark, the other prospect expansive and bright – is one of those aspects that run through the entire DMAA portfolio, from private houses and apartments to large public buildings. Instead of a formal system, the office tends to view architecture as a stage for actions.In particular, the conditions of entering, traversing and viewing the building are carefully arranged, linking spaces together through a situated gaze.

Performative

Performativity is crucial to the work of DMAA. In particular with their public buildings,it is clear that the design is not derived from an analysis of site, program or typology;instead, the context, the activities and the types are really e ff ects of the architecture.Before it is constructed, we don’t even know what a DMAA building is capable of because the architectural intervention affects cultural perceptions and socialconventions. The performative qualities are enhanced also by the shapes of the buildings. In addition to its beauty, the complex folded geometry functions much like the sculptures of Robert Morris and other minimalists in the 1960s: by constantly transforming itself, the shape invites the viewer to explore the building from allperspectives.

For an early critic of minimal sculpture, Michael Fried, such interdependence of the work and the viewer actually compromised the purity of art. He argued that minimalist pieces are implicitly anthropomorphic, confrontational and “theatrical” in that they implicate the scale of the body of the viewer and require him to complete the web of relationships projected by the work. If we try to apply this discussion to architecture, however, it soon becomes clear that the aspects of theatricality which Fried criticizes in minimalism – including the commingling of the space of the viewer and the space of the work, the temporal unfolding of the experience of the work and the somatic apprehension of scale – are the very stu ff of architecture, especially as regards the projects by DMAA.

Physiology

As opposed to many contemporary practices that try to ground their work on extraarchitectural theories, DMAA operate with literal, as opposed to depicted, shape.This approach derives its force from a visceral juxtaposition of the human body with the architectural setting where the meaning of the form is in the action it generates.In a way, then, the office approaches the kind of physiological aesthetics that Nietzsche promised.

Despite the spectacular appearance of many DMAA projects, their architecture does not work solely for the eyes but rather organizes the speeds of moving bodies. What counts in the experience of space is the body as a system of possible actions, and, as Maurice Merleau-Ponty used to say, “my body is wherever there is something to be done.” That is why space cannot be thought of without reference to body, function and time.

To take a simple example of the physiological approach, consider a project from 2004, the city lofts in Wienerberg in Vienna. The facades suggest an interest in the skin of the building as an independent element and present a skillful investigation into contemporary ornament. Still, what is most signi fi cant in the building can be best appreciated in section. Instead of stacking identical, 2.5 meter high fl oors on top of

each other, the design combines zones with di ff erent fl oor heights into a complex,interlocking Raumplan, allowing the height of 3.40 m for living areas on the southern side of the building but using 2.40m for more intimate zones of relaxation or sleep in the north. An unusual variety of apartment types and spatial conditions result from this apparently simple concept that responds to the functional, physiological and anatomical requirements of the body.

The sublime

Although DMAA can be said to have turned Fried’s critique of theatricality around,there are many big di ff erences between architecture and sculpture, and one has to do with scale. As Edmund Burke recognized in his theory of the sublime, published in 1757, vast size opens up a whole new set of aesthetic effects, in particular the experience of the sublime. While huge dimensions always tend to evoke the sublime, Burke argues that height is much more e ff ective than length or breadth,because it confronts and thematizes the physiological limits of the human body, and a gigantic cantilever – as in the Porsche museum or the Darat King Abdullah II for Culture and Arts, for example – that resists the forces of gravity in a way we never encounter in nature certainly produces the most radical of such e ff ects.

Claiming that the experience of the sublime was the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling, Burke further explained that “the mind is so entirely filled with its object, that it cannot entertain any other, nor by consequence reason on that object which employs it.” However, it is not the object that would be sublime in itself. Instead, the e ff ect is created by the human mind confronted by something that resists de fi nition. For Burke and Immanuel Kant, the sublime is not classi fi able or determinable: it arises from the attempt to present the unpresentable, the invisible within the visible. That is why architecture that aspires to the sublime must reject fi guration, representation and indexicality, as well as other impediments of memory,association, nostalgia, legend, or myth. The spirit of our times, according to Jean-Francois Lyotard, is surely “that of the immanent sublime, that of alluding to the nondemonstrable.”

Skin

Since the work of DMAA is so involved with the e ff ects of the sublime, one should not look for a hidden meaning, a secret, that criticism should dig out and bring to the open. The walls of their buildings are not hiding anything behind them: instead, they are the secret. In a paraphrase of Paul Valéry, we could suggest that the deepest in the architecture of DMAA is the skin.

In recent years, architecture has increasingly faced the danger of being reduced to a mere design of attractive surfaces (with or without a media façade). At first glance, DMAA’s experiments with ornamentation, as in the housing projects on the Wimbergergasse or Paltramplatz, seem to betray a similar interest in twodimensionality. However, for them, there can be as much real architecture in the skin as in the urban strategy or overall building shape: also the skin is a toolfor organizing spatial and social relationships, not just a delimiting surface or a billboard.

While a sculpture functions as an object of visual observation from the outside,architecture provides not only external aesthetic qualities but also thresholds that allow or deny access to the interior. The skins that open and close architecturalspaces de fi ne levels of publicity and privacy by filtering visual, acoustic, physicaland other connections. As with biological organisms, the architectural skin is in reality not a two-dimensional surface but in many of their projects rather an organ that de fi nes a space in itself.

One of the secrets of DMAA is their ability to apply the same principles and the same three-dimensional thinking across scales and materials, simultaneously focusing on both aesthetic appearance and performative force of every element.