妇女乳腺癌医院出院率与在含持久性有机污染物场地邮政区居住之间的关系

卢晓霞, Lawrence Lessner, David O. Carpenter,#

1. 北京大学城市与环境学院 地表过程分析与模拟教育部重点实验室,北京 100871 2. 纽约州立大学奥尔巴尼分校 健康与环境研究所,纽约 12144

妇女乳腺癌医院出院率与在含持久性有机污染物场地邮政区居住之间的关系

卢晓霞1,, Lawrence Lessner2, David O. Carpenter2,#

1. 北京大学城市与环境学院 地表过程分析与模拟教育部重点实验室,北京 100871 2. 纽约州立大学奥尔巴尼分校 健康与环境研究所,纽约 12144

持久性有机污染物(persistent organic pollutants,简称POPs)大多具有毒性,有的甚至致癌,但目前对POPs引起的健康风险仍知之甚少。本研究的假设是在含POPs场地邮政区居住妇女的乳腺癌风险增大。从纽约州计划与研究合作系统(SPARCS)等数据库中收集乳腺癌患者的信息及居住地危险废弃物暴露、经济收入和城市化等数据。以邮政区编码表征居住地,采用负二项回归方法,对纽约州30岁以上妇女乳腺癌医院出院率进行了模型分析,参数包括种族、年龄、污染暴露、经济收入和城市化率。结果显示,不同参数之间(如暴露与种族、暴露与收入、暴露与城市化)存在交互作用。对部分子群而言,与居住在不含危险废弃物场地邮政区的妇女相比,居住在含POPs场地邮政区的妇女乳腺癌出院率显著升高(率比(rate ratio, RR) 1.10 ~ 1.34,P < 0.05)。这种关系在非裔妇女中强于白种妇女、在城市化高的地区强于农村地区。调整了混杂因素后,某些妇女人群乳腺癌出院率升高与在含POPs场地邮政区居住有显著的关系。

持久性有机污染物;乳腺癌;医院出院率;妇女;居住

Received 14 December 2015 accepted 20 January 2016

乳腺癌是世界上最常见的浸润性肿瘤,也是妇女癌症死亡的主要原因[1]。Lichtenstein等[2]在一项针对双胞胎的研究中得出结论,27%的乳腺癌归因于遗传因素,剩余的可能归因于“环境因素”。越来越多的证据表明,暴露于化学品可引起乳腺癌的发生[3-6]。Rudel等[7]根据国际癌症研究机构、美国国家毒理学计划和其他来源的研究,发现216种化学品与乳腺肿瘤的增加有关,其中包括持久性有机污染物(persistent organic pollutants,简称POPs),如多环芳烃(PAHs)、有机氯农药等。

POPs为潜在的内分泌干扰物,它们会干扰对激素敏感的组织功能,导致激素信号转导和细胞功能失调。Reaves等[8]的研究表明,通过饮食暴露的POPs会蓄积在脂肪组织中,促进肥胖的发展,并最终影响乳腺癌的发展或进展。Liu等[9]报道多氯联苯(PCBs)会通过激活Rho相关激酶增强乳腺癌细胞的转移特性。Zhang等[10]进行元分析,从观察性研究中评估环境PCBs暴露和乳腺癌风险之间的关系,发现第II组(潜在的抗雌激素和免疫毒性的类二噁英)和第III组(苯巴比妥,CYP1A和CYP2B诱导物,生物持久性)PCBs暴露可能对乳腺癌风险有贡献,但第I组(潜在的雌激素)PCBs或总PCBs暴露没有。Ghisari等[11]在一项针对格陵兰因纽特妇女的研究中,发现BRCA1、CYP1A1和CYP17基因多态性可增加乳腺癌的风险,这种风险随着血浆中全氟辛烷磺酰基化合物(PFOS)和全氟辛酸铵(PFOA)的水平增高而增大。血浆氟代化合物(PFAS)是乳腺癌的一个风险因子,但个体间多态性差异可能会造成对PFAS/POP暴露的敏感性差异。Zhang等[12]的研究表明,受环境PCBs暴露妇女体内CYP1A1 m2多态性可能增加乳腺癌的风险。Arrebola等[13]发现妇女乳腺癌风险和血浆中β-六六六(β-HCH)水平显著相关。White等[14]报道RARb基因特异甲基化可能与PAH-DNA加合物反应,增加激素受体阳性乳腺癌的风险。

在危险废弃物场地附近居住,可能会受到污染物的暴露,引发病症。已有研究报道,在含危险废弃物场地的郡居住,男性肺癌、膀胱癌、食道癌、胃癌、大肠癌和直肠癌以及女性肺癌、乳腺癌、膀胱癌、胃癌、大肠癌和直肠癌的死亡率高于不含危险废弃物场地的郡[15]。本研究的假设是在含POPs场地邮政区居住妇女的乳腺癌风险增大。为此,从纽约州计划与研究合作系统(SPARCS)数据库等来源中收集有关数据和信息,通过统计分析,旨在确定妇女乳腺癌医院出院率与在含POPs场地邮政区居住之间的关系。

1 材料与方法(Materials and methods)

1.1 研究人群

从纽约州计划与研究合作系统(SPARCS)数据库中获得1993年至2008年期间从纽约州医院出院的乳腺癌患者的数据。患者信息包括年龄、性别、种族、以及居住地邮政编码。妇女乳腺癌的诊断代码为174.0、174.1、174.2、174.3、174.4、174.5、174.6、174.8和174.9。纽约市的情况比较特别,环境状况及市民行为都与其他地方不同,因而没有包含在本研究中。在所研究的患者中,84.6%为白种人,6.3%为非裔,0.2%为印第安人,1.1%为亚裔,3.5%为其他种族,4.8%为未知。由于白种人和非裔共占患者的90%以上,本研究中仅対这2个种族的人群进行研究。由于年龄在30岁以下的患者仅占总患者的0.5%,因此这部分人群不包含在本研究中。对30岁及以上的人群,分为6个水平:年龄段1 (30 ~ 39岁)、年龄段2 (40 ~ 49岁)、年龄段3 (50 ~ 59岁)、年龄段4 (60 ~ 69岁)、年龄段5 (70 ~ 79岁)、年龄段6 (80岁及以上)。

从Claritas公司(圣地亚哥,美国)收集1993年至2008年按邮政编码给出的家庭收入中值(MHI)数据。MHI被用于作为社会经济状况的表征。已有研究显示,由MHI衡量的极端社会经济状况人群具有与普通人不同的获得健康服务的行为[16]。因此,本研究仅取MHI分布中位于第10个($ 26 151)至第90个($ 58 673)百分点的邮政编码区进行分析。在该范围内,MHI进一步根据四分位数分为4个水平:第一个四分位数(1stQ) $ 26 151~32 853、第二个四分位数(2ndQ) $ 32 853~39 047、第三个四分位数(3rdQ) $ 39 047~51 909、第四个四分位数(4thQ) $ 51 909~58 673。根据美国人口调查局关于城市地区的定义(每平方英里人数在1 000以上)[16],采用2000年的调查数据将邮政编码区分为3个城市化水平:低城市化率(UR1,少于25%的人群居住在城市地区,如农村)、中城市化率(UR2,25 ~ 75%的人群居住在城市地区)、高城市化率(UR3,大于75%的人群居住在城市地区)。从纽约州环境保护部收集危险废弃物场地信息,包括场地的位置和主要污染物。

1.2 暴露评估

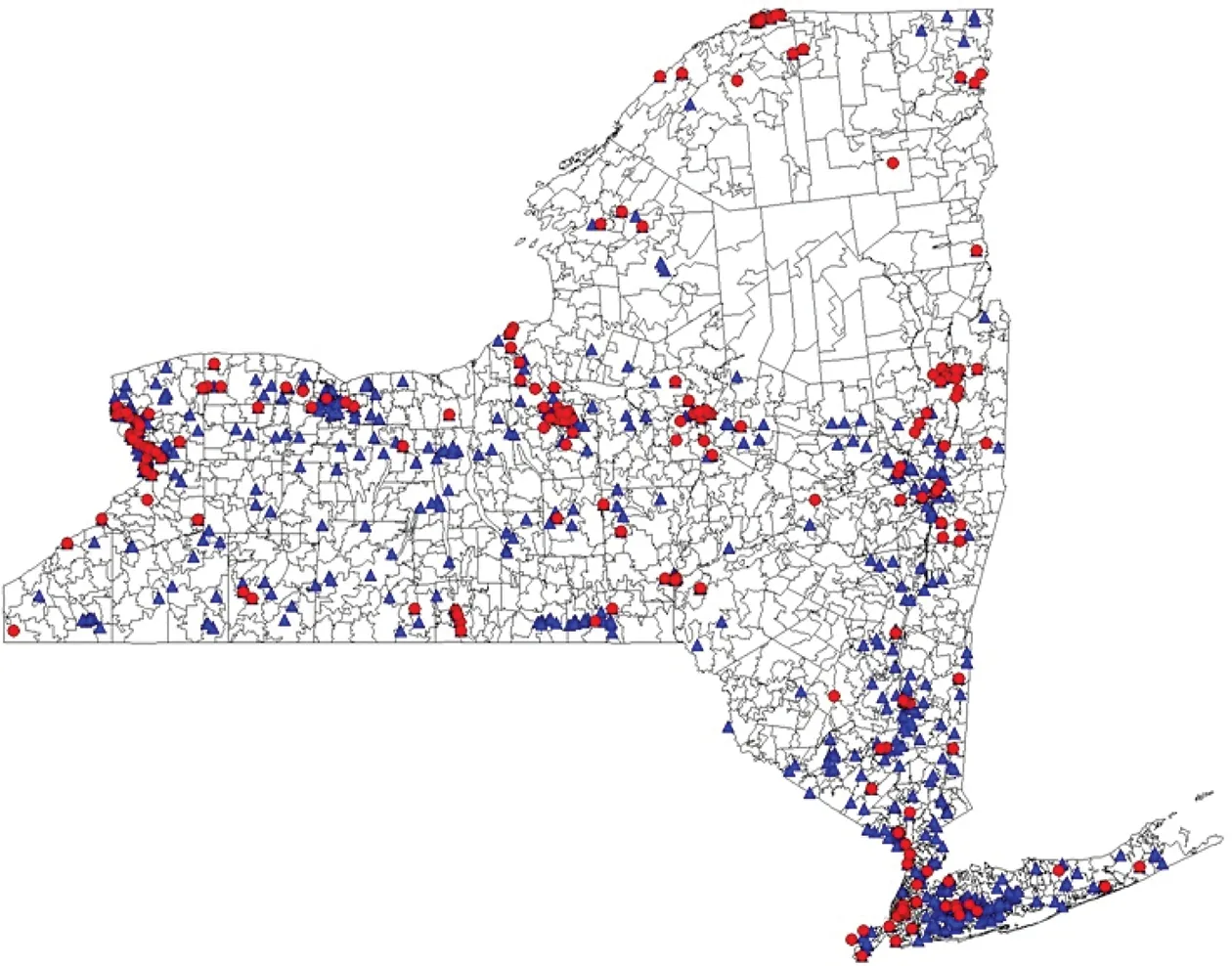

纽约州环境保护部鉴定出818个对人体健康有潜在威胁的危险废弃物场地,它们分布在纽约州416个邮政编码区,如图1所示。危险废弃物场地中的污染物包括POPs(二噁英、PCBs、PAHs、有机氯农药等)、挥发性有机污染物(氯乙烯类、氯乙烷类、氯甲烷类、氯苯类、苯系物等)和其他污染物(重金属、邻苯二甲酸盐、酸、放射性物质等)。由于受高浓度PCBs污染,从哈德逊瀑布到曼哈顿200英里的哈德逊河都被美国环保局列为国家优先名单中的一个危险废弃物场地,因此与哈德逊河毗邻的47个邮政编码区都被视为污染物暴露区[17]。根据场地污染物类型,将暴露分为3个水平:POPs区(至少含有1个POPs场地)、其他污染区(不含POPs但含其他危险废弃物场地)、干净区(不含任何危险废弃物场地)。

图1 纽约州危险废弃物场地的分布(•POPs场地,▲其他污染物场地)Fig. 1 Distribution of hazardous waste sites in New York State (•POPs site, ▲other waste site)

1.3 统计分析

采用SAS软件(版本9.3,SAS软件研究所,美国)进行统计分析,根据负二项回归模型拟合数据。模拟过程中,先只考虑主效应,然后在主效应模型中加入暴露与年龄、种族、收入和城市化率的交互作用。模型公式如下:

Log (乳腺癌住院人数) = Log (总人年数)+截距+b1×暴露2+b2×暴露3 +b3×种族2+b4×年龄2+b5×年龄3+b6×年龄4+b7×年龄5+b8×年龄6+b9×收入2+b10×收入3+b11×收入4+b12×城市化率2+b13×城市化率3+交互作用

蛇葡萄素F对脂多糖致炎模型细胞的抗炎作用及其机制研究 ……………………………………………… 梁晓玲等(14):1927

公式中,暴露1是指不含任何危险废弃物场地;暴露2是指含POPs场地;暴露3是指不含POPs但含其他危险废弃物;种族1是指白种美国妇女;种族2是指非裔美国妇女;年龄1是指30 ~ 39岁;年龄2是指40 ~ 49岁;年龄3是指50 ~ 59岁;年龄4是指60 ~ 69岁;年龄5是指70 ~ 79岁;年龄6是指80岁及以上;收入1是指家庭收入中值为$26 151 ~ $32 853;收入2是指家庭收入中值为$32 853 ~ $39 047;收入3是指家庭收入中值为$39 047 ~ $51 909;收入4是指家庭收入中值为$51 909 ~ $58 673;城市化率1是指少于25%的人群居住在城市地区;城市化率2是指25% ~ 75%的人群居住在城市地区;城市化率3是指大于75%的人群居住在城市地区;b1~b13为拟合系数。

2 结果(Results)

2.1 研究人群的特征

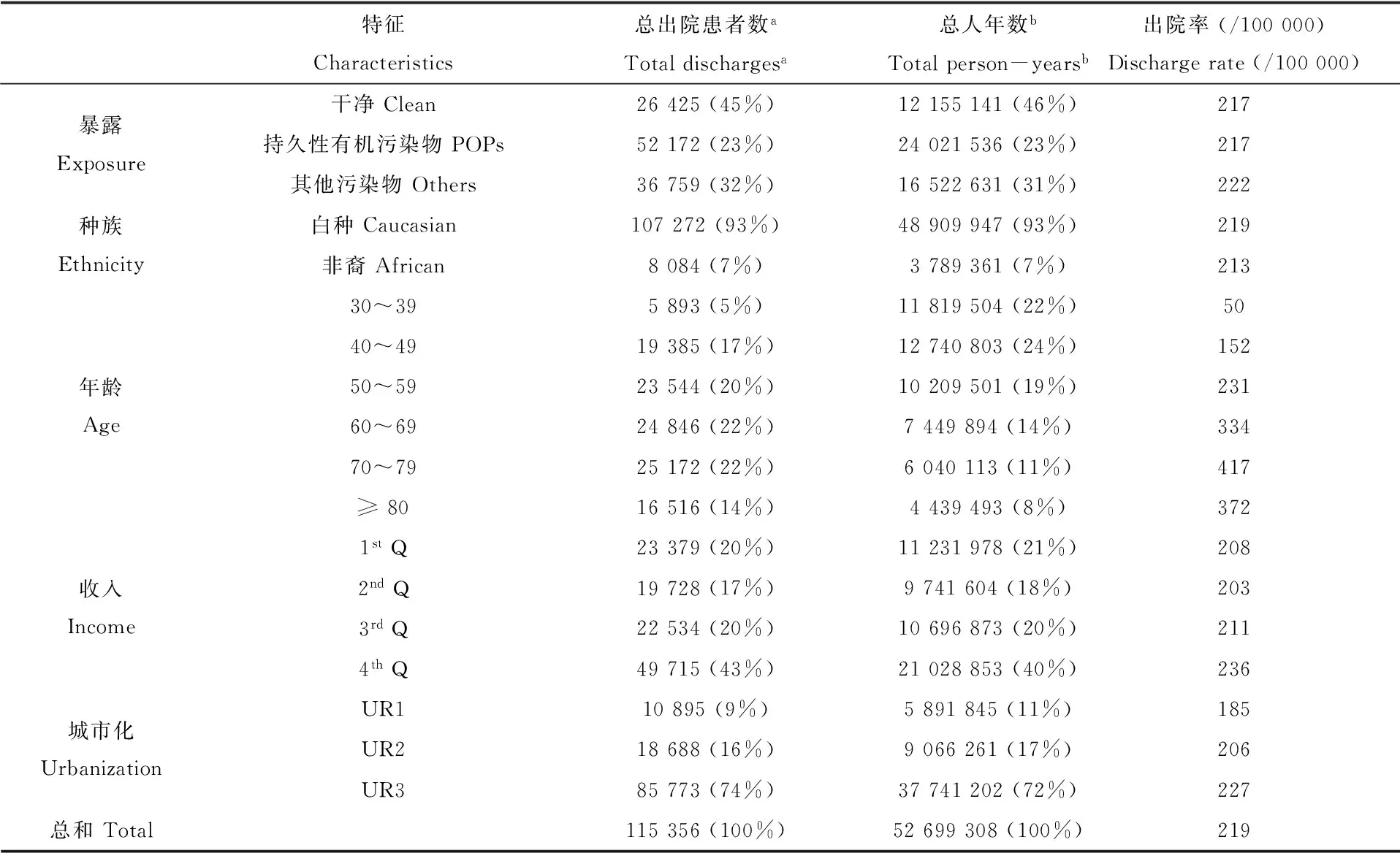

在研究人群中,约23%居住在含POPs场地邮政区,约31%居住在不含POPs但含其他危险废弃物场地邮政区,约46%居住在不含任何危险废弃物场地邮政区。在不考虑混杂因素的情况下,POPs区、其他污染区和干净区的乳腺癌出院率分别为217/100 000、222/100 000和217/100 000,白种美国妇女的乳腺癌出院率(219/100 000)高于非裔美国妇女(213/100 000),乳腺癌出院率随年龄增大(在30 ~ 79岁范围内)、收入增大、以及城市化率增大而增高。表1列出研究人群的特征。

2.2 模型分析

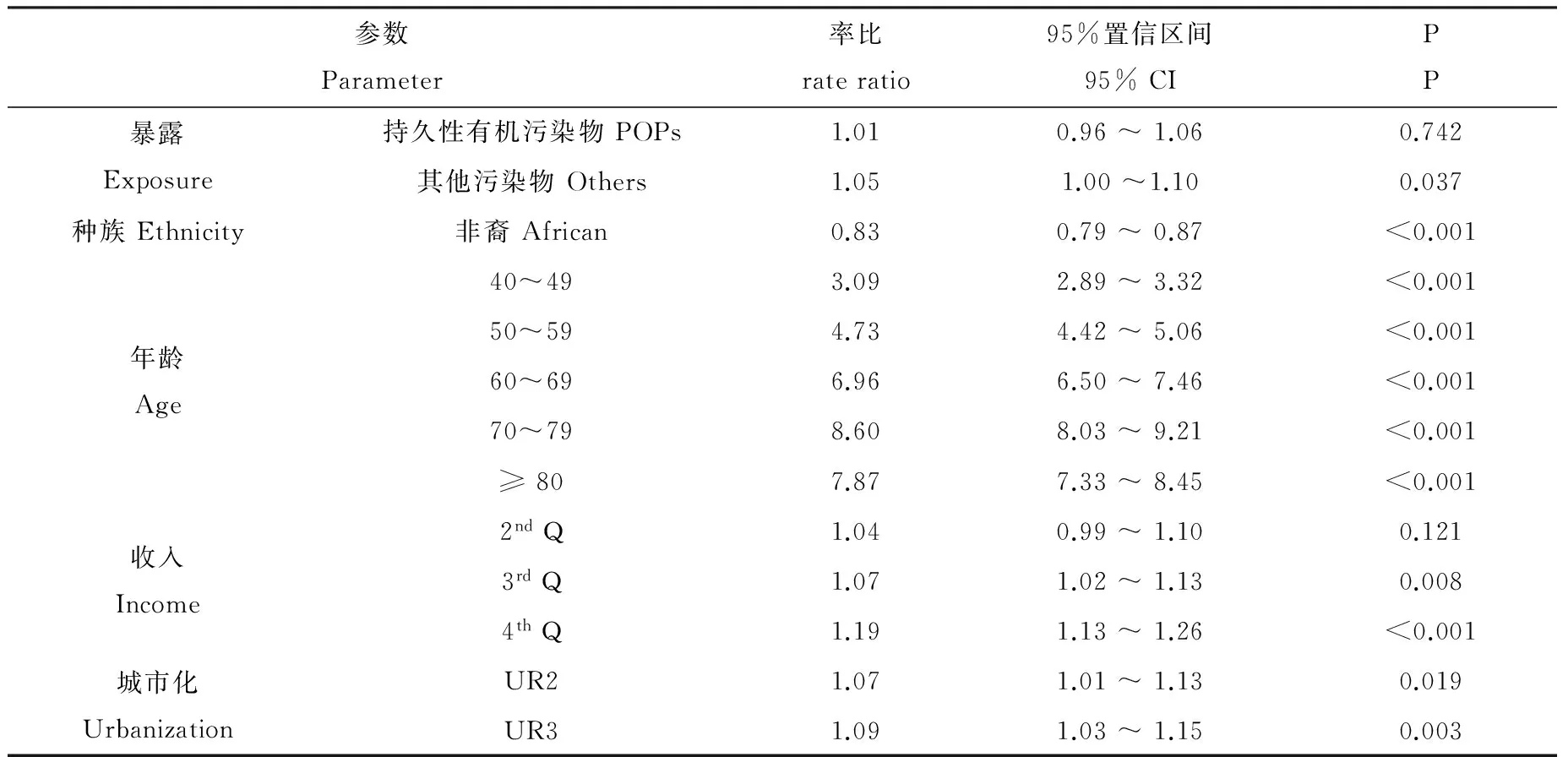

首先对主效应模型进行了分析,结果如表2所示。POPs区妇女乳腺癌医院出院率与干净区相比没有明显差异(率比(RR)为1.01,95%置信区间(95% CI)为0.96 ~ 1.06,P =0.742),而其他污染区妇女乳腺癌出院率与干净区相比显著升高(RR为1.05,95% CI为1.00 ~ 1.10,P =0.037)。非裔妇女乳腺癌出院率与白种妇女相比显著降低(RR为1.83,95% CI为0.79 ~ 0.87,P < 0.001)。与30 ~ 39岁年龄段妇女相比,高年龄段的妇女乳腺癌出院率显著升高,且RR在40 ~ 79岁范围内随年龄增大而增大。与低收入(1stQ)妇女相比,高收入(3rdQ和4thQ)妇女乳腺癌出院率显著升高。与城市率低地区(UR1)妇女相比,城市率较高地区(UR2和UR3)妇女乳腺癌出院率显著升高。这些发现与其他研究报道的结果基本一致[18-19]。

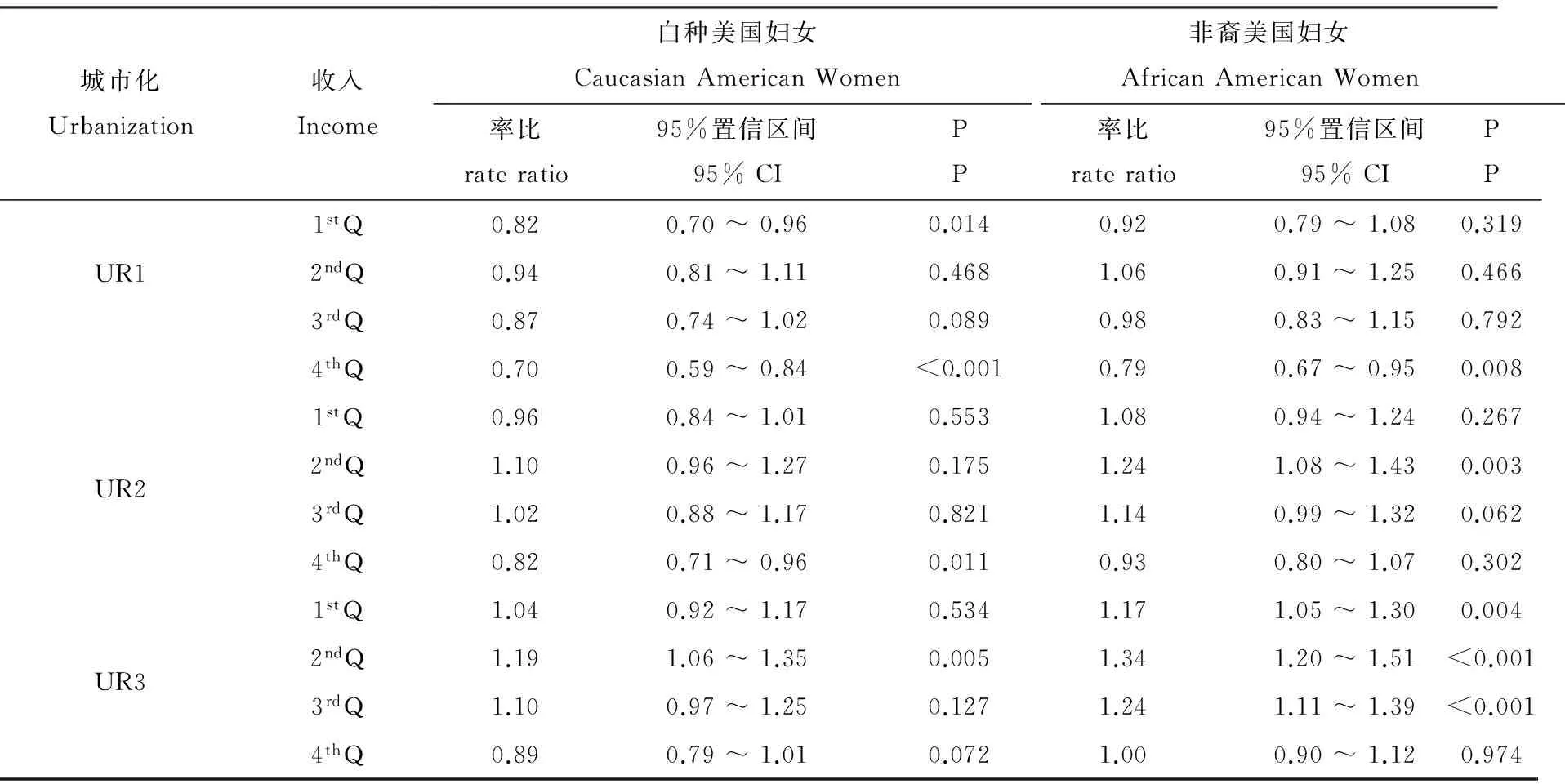

为了提高模型精度,进一步阐明暴露与妇女乳腺癌的关系,在模型中加入了暴露与混杂因素的交互作用。结果显示,暴露与年龄之间的交互作用不显著,因而从模型中去除。暴露与其他混杂因素的交互作用显著。表3列出POPs区与干净区相比不同子群妇女乳腺癌出院率的率比。

在城市化高的地方(UR3),POPs区与干净区相比,除高收入(4thQ)子群之外的非裔美国妇女乳腺癌出院率都显著升高(幅度为17% ~ 34%),而白种美国妇女中只有中低收入(2ndQ)子群乳腺癌出院率显著升高(幅度为19%)。在城市化中等的地方(UR2),POPs区与干净区相比,仅中等收入(2ndQ和3rdQ)的非裔美国妇女乳腺癌出院率显著升高(幅度为24%和14%)。在城市化低的地区(UR1),POPs区与干净区相比,非裔和白种美国妇女乳腺癌出院率均无显著升高,对高收入(4thQ)子群而言甚至呈现显著降低现象,同样现象也发生在低收入(1stQ)白种美国妇女群中。

表1 研究人群的特征

注:a括号内为占总出院患者数的比例;b括号内为占总人年数的比例;1st、2nd、3rd和4th分别表示收入为26 151~32 853,32 853~39 047,39 047~51 909,51 909~58 673,UR1、UR2、UR3表示城市化率为<25%, 25%~75%, >75%。

Note:aNumber in parentheses is percentage of the total number of discharged patients;bNumber in parentheses is percentage of the total person-years;1st, 2nd, 3rdand 4threpresent the income of26 151-32 853,32 853-39 047,39 047-51 909,51 909-58 673; UR1, UR2, UR3 represent urbanization rate of <25%, 25%-75%, >75%.

3 讨论(Discussion)

通常环境暴露被认为是乳腺癌的一个危险因素,但明确的证据是有限的。Brody等[20]识别了152篇关于环境污染物与乳腺癌流行病学研究的文章,其中约57%使用生物测量描述暴露,约20%使用地理位置描述暴露。大多数研究未发现乳腺癌风险与POPs有强关联性,仅有个别研究显示乳腺癌与某些PCBs同系物单体有关联,以及在一些带有CYP1A1-m2基因变型的绝经妇女中乳腺癌与体内总PCBs浓度相关[21-23]。国际癌症研究机构(International Agency for Research on Cancer,简称IARC)将PCBs定为第一组人类致癌物,认为PCBs暴露与乳腺癌之间的特定关联是“有限”的因果关系的证据。

表2 作为暴露、种族、年龄、收入和城市化函数的妇女乳腺癌出院率比

表3 POPs区与干净区相比不同子群妇女乳腺癌医院出院率的率比

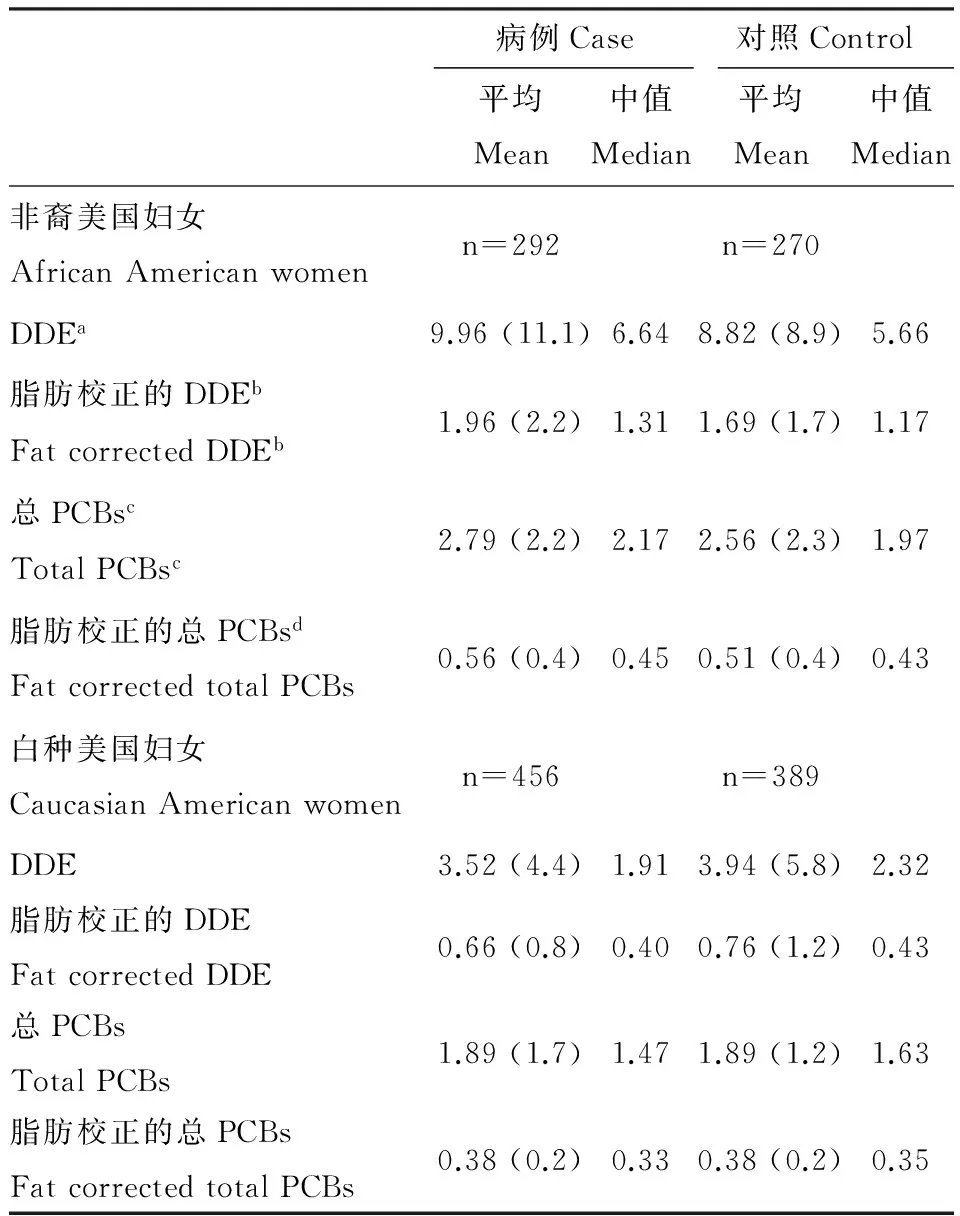

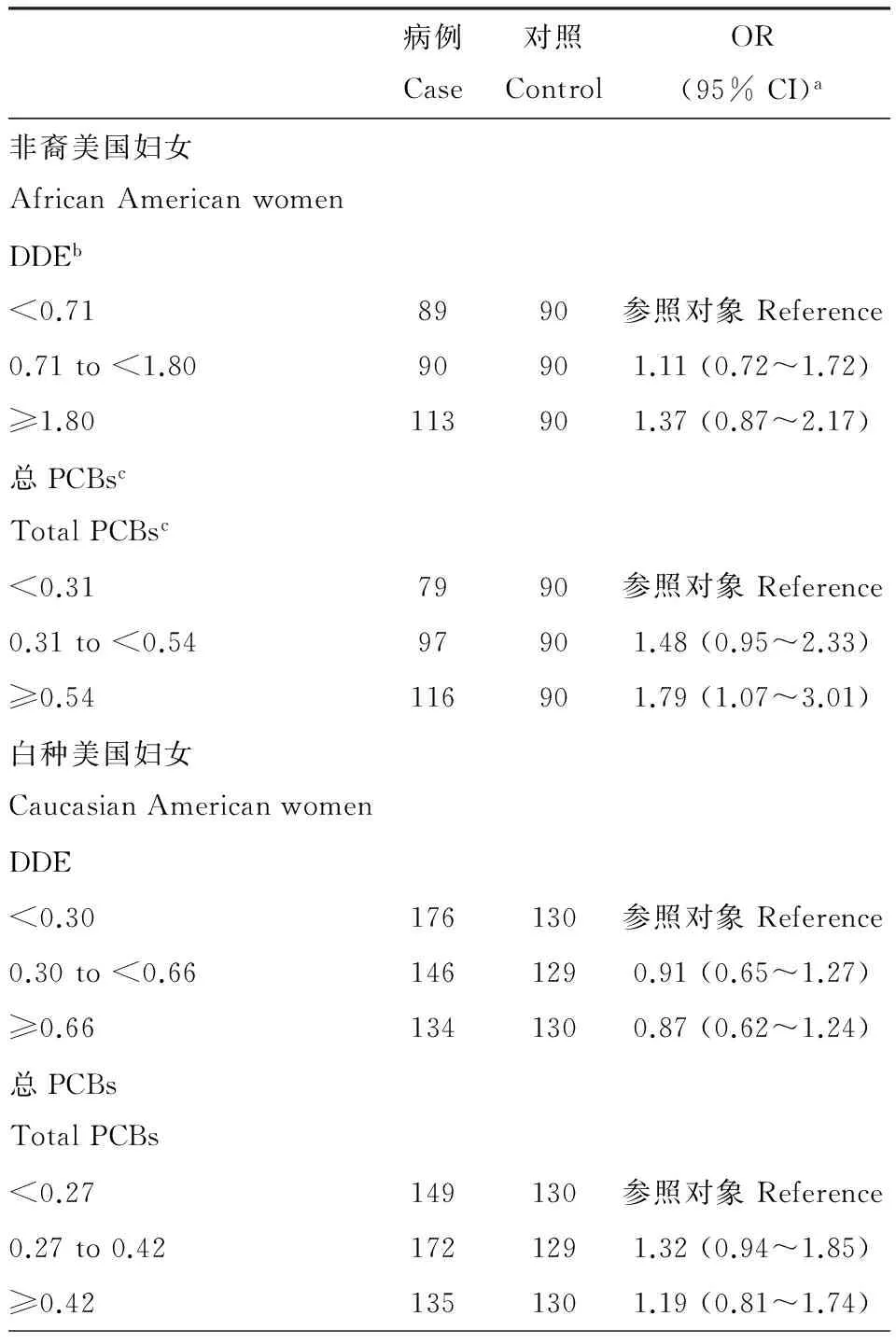

一些研究者报道基因多态性会引发乳腺癌风险[22-25]。据报道,CYP1A1-m2基因变型(一种乳腺癌风险因素)在非裔美国妇女体内存在的频率为白种美国妇女的3倍多(在白种美国妇女体内的存在频率为10% ~ 15%)[26-27]。也有研究发现非裔美国妇女体内的POPs含量比白种美国妇女高[28-29]。表4显示美国北卡罗莱纳州乳腺癌研究中非裔美国妇女和白种妇女血浆中1,1-双(对氯苯基)-2,2-二氯乙烯(DDE)和总多氯联苯(PCBs)的浓度[29]。表5显示根据DDE和总PCBs浓度确定的乳腺癌比值比[29]。

表4 美国北卡罗莱纳州乳腺癌研究中非裔美国妇女和白种妇女血浆中DDE和PCBs浓度

注:ap,p’-DDE浓度单位ng·mL-1,未经脂肪校正;bp,p’-DDE 浓度单位μg·g-1,经脂肪校正;c总PCBs 浓度单位ng·mL-1,未经脂肪校正;d总PCBs浓度单位μg·g-1,经脂肪校正。

Note:ap,p’-DDE concentration unit ng·mL-1, not corrected by fat;bp,p’-DDE concentration unit μg·g-1, corrected by fat;ctotal PCBs concentration unit ng·mL-1, not corrected by fat;dtotal PCBs concentration unit μg·g-1, corrected by fat.

因此,本研究中观察到的POPs暴露与乳腺癌关联在种族上的差异可能与基因因素和暴露因素都有关系。其他因素如生活方式、种族隔离、文化习俗等都可能会造成所观察到的种族差异。

在城市化水平较高地方居住的妇女乳腺癌医院出院率高于农村的妇女。在城市地区可能有一些有重叠的危险污染源,如机动车的尾气、工厂排放的有毒废气等。本研究中,从美国环境保护局收集了1993年至2008年期间纽约州毒物释放清单(toxic release inventory,简称TRI)场地数据[30],并对它们与妇女乳腺癌出院率的关系进行了测试,结果显示两者无显著关联(RR为1.00,95% CI为0.96 ~ 1.04,P =0.907)。由于没有这些场地的释放物信息,因此对TRI暴露的评估不是基于化学品。农村面积通常较大,居民受危险废弃物暴露的影响较小。

表5 根据DDE和总PCBs浓度确定的乳腺癌比值比

注:a调整了年龄的影响,95% CI为95%置信区间;bp,p’-DDE 浓度单位 μg·g-1,经脂肪校正;c总PCBs浓度单位 μg·g-1,经脂肪校正。Note:aAdjusted the influence of age, 95% CI was 95% confidence interval;bp,p’-DDE concentration unit μg·g-1, corrected by fat;cTotal PCBs concentration unit μg·g-1, corrected by fat.

低收入人群比高收入人群更有可能居住在含危险废弃物场地的邮政区[31],这使得评估社会经济状况的影响有点复杂。低收入人群中一些乳腺癌患者可能无钱就医,他们的信息无法被医院收集。高收入人群中一些乳腺癌患者可能有特殊的治疗渠道,他们的信息也无法被医院收集。这些不足可能会导致低估社会经济状况与乳腺癌风险的真实关系。

本文研究有优势,也有不足。优势体现在:数据量大,收集了1993年至2008年整个纽约州公立医院的数据;研究中有种族、年龄、收入和城市化控制数据;研究中考虑了暴露与其他混杂因素之间的交互作用。不足体现在:SPARCS数据库仅含有出院数据,没有显示某一个患者是第几次入院,也没有在州外就医患者的信息。研究中不具备对一些重要混杂因素的控制数据,如遗传、暴露年龄、月经初潮年龄、生育情况、体质指数、饮食、酒精消费情况、激素替代治疗等。对污染暴露的分类不完全精确。例如,邮政区的大小不一,居民受危险废弃物场地暴露的影响差别较大。研究中没有个人水平的社会经济状况信息,仅用家庭收入中值来代替某个邮政区所有居民的社会经济状况。尽管如此,本研究可在一定程度上说明POPs场地暴露对妇女乳腺癌风险的影响。

综上可知:调整混杂因素后,部分妇女乳腺癌出院率的升高与在含有POPs场地邮政区居住有显著的关系,这种关系在非裔妇女中强于白种妇女、在城市化高的地区强于城市化低的地方、在中低收入群中强于其他收入群。

[1] Brody J G, Rudel R A, Michels K B, et al. Environmental pollutants, diet, physical activity, body size, and breast cancer [J]. Cancer, 2007, 109: 2627-2634

[2] Lichtenstein P, Holm N V, Verkasalo P K, et al. Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer--analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland [J]. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2000, 343(2): 78-85

[3] Ann A, Sarah R, David O. Perchloroethylene-contaminated drinking water and the risk of breast cancer: Additional results from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, USA [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2003, 111(2): 167-173

[4] Zhang Y, Wise J P, Holford T R, et al. Serum polychlorinated biphenyls, cytochrome P-4501A1 polymorphisms, and risk of breast cancer in Connecticut women [J]. American Journal of Epidemiology, 2004, 160(12): 1177-1183

[5] Bonner M R, Han D, Nie J, et al. Breast cancer risk and exposure in early life to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons using total suspended particulates as a proxy measure [J]. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 2005, 14(1): 53-60

[6] Engel L S, Hill D A, Hoppin J A, et al. Pesticide use and breast cancer risk among farmers' wives in the agricultural health study [J]. American Journal of Epidemiology, 2005, 161(2): 121-135

[7] Rudel R A, Attfield K R, Schifano J N, et al. Chemicals causing mammary gland tumors in animals signal new directions for epidemiology, chemicals testing, and risk assessment for breast cancer prevention [J]. Cancer, 2007, 109 (12S): 2635-2666

[8] Denise K R, Ginsburg E, Bang J J, et al. Persistent organic pollutants and obesity: Are they potential mechanisms for breast cancer promotion? [J] Endocrine-Related Cancer, 2015, 22(2): R69-R86

[9] Liu S J, Li S T, Du Y G. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) enhance metastatic properties of breast cancer cells by activating Rho associated Kinase (ROCK) [J]. PLoS One, 2010, 5(6): e11272

[10] Zhang J W, Huang Y, Wang X L, et al. Environmental polychlorinated biphenyl exposure and breast cancer risk:A meta-analysis of observational studies [J]. PLOS One, 2015, DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0142513

[11] Ghisari M, Eiberg H, Long M H, et al. Polymorphisms in phase I and phase II genes and breast cancer risk and relations to persistent organic pollutant exposure: A case-control study in Inuit women [J]. Environmental Health, 2014, 13(1): 19

[12] Zhang Y W, Wise J P, Holford T R, et al. Serum polychlorinated biphenyls, cytochrome P-450 1A1 polymorphisms, and risk of breast cancer in Connecticut women [J]. American Journal of Epidemiology, 2004, 60(12): 1177-1183

[13] Arrebola J P, Belhassen H, Artacho-Cordón F, et al. Risk of female breast cancer and serum concentrations of organochlorine pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls: A case-control study in Tunisia [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2015, 520: 106-113

[14] White A J, Chen J, McCullough L E, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH)-DNA adducts and breast cancer: Modification by gene promoter methylation in a population-based study [J]. Cancer Causes Control, 2015, 26: 1791-1802

[15] Griffith J, Duncan R, Riggan W, et al. Cancer mortality in U.S. counties with hazardous waste sites and ground water pollution [J]. Archives of Environmental Health, 1989, 44(2): 69-74

[16] Ma J, Kouznetsova M, Lessner L, et al. Asthma and infectious respiratory disease in children - correlation to residence near hazardous waste sites [J]. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews, 2007, 8(4): 292-298

[17] Sergeev A V, Carpenter D O. Hospitalization rates for coronary heart disease in relation to residence near areas contaminated with persistent organic pollutants and others [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2005, 113(6): 756-761

[18] Brody J G, Rudel R A. Environmental pollutants and breast cancer [J]. Environmental Health Perspective, 2003,11(8): 1007-1019

[19] Harper S, Lynch J, Meersman S C, et al. Trends in area-socioeconomic and race-ethnic disparities in breast cancer incidence, stage at diagnosis, screening, mortality, and survival among women ages 50 years and over (1987-2005) [J]. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 2009, 18(1): 121-131

[20] Brody J G, Moysich K B, Humblet O, et al. Environmental pollutants and breast cancer: Epidemiologic studies [J]. Cancer, 2007, 109(12S): 2667-2711

[21] Aronson K J, Miller A B, Woolcott C G, et al. Breast adipose tissue concentrations of polychlorinated biphenyls and other organochlorines and breast cancer risk [J]. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 2000, 9: 55-63

[22] Moysich K B, Shields P G, Freudenheim J L, et al. Polychlorinated biphenyls, cytochrome P4501A1 polymorphism, and postmenopausal breast cancer risk [J]. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 1999, 8: 41-44

[23] Laden F, Ishibe N, Hankinson S E, et al. Polychlorinated biphenyls, cytochrome P450 1A1, and breast cancer risk in thenurses’ health study [J]. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 2002, 11: 1560-1565

[24] Zheng W, Xie D W, Jin F, et al. Genetic polymorphism of cytochrome P450-1B1 and risk of breast cancer [J]. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 2000, 9: 147-150

[25] Figueiredo J C, Knight J A, Briollais L,et al. Polymorphisms XRCC1-R399Q and XRCC3-T241M and the risk of breast cancer at the Ontario site of the Breast Cancer Family Registry [J]. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 2004, 13: 583-591

[26] Shields P G, Caporaso N E, Falk R T, et al. Lung cancer, race and a CYP1A1 polymorphism [J]. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 1993, 2: 481-485

[27] Li Y, Millikan R C, Bell D A, et al. Polychlorinated biphenyls, cytochrome P450 1A1 (CYP1A1) polymorphisms, and breast cancer risk among African American women and white women in North Carolina: A population-based case-control study [J]. Breast Cancer Research, 2005, 7(1): R12-R18

[28] Millikan R, DeVoto E, Duell E J, et al. Dichlorodiphenyldichloroethene, polychlorinated biphenyls, and breast cancer among African-American and white women in North Carolina [J]. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 2000, 9: 1233-1240

[29] Goncharov A, Bloom M, Pavuk M, et al. Blood pressure and hypertension in relation to levels of serum polychlorinated biphenyls in residents of Anniston, Alabama [J]. Journal of Hypertension, 2010, 28(10): 2053-2060

[30] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) Program [OL]. http://www2.epa.gov/toxics-release-inventory-tri-program/tri-basic-data-files-calendar-years-1987-2011.

[31] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Population Characteristics and Environmental Health [OL]. http://ephtracking.cdc.gov/showPopCharEnv.action.

◆

Association between Hospital Discharge Rate for Female Breast Cancer and Residence in Zip Code Containing Persistent Organic Pollutants

Lu Xiaoxia1,*, Lawrence Lessner2, David O. Carpenter2,#

1. Laboratory for Earth Surface Processes, Ministry of Education, College of Urban and Environmental Sciences, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China 2. Institute for Health and the Environment, University at Albany, State University of New York, New York 12144, USA

Persistent organic pollutants (in abbreviation, POPs) are mostly toxic, with some even carcinogenic; however, currently the health risks caused by POPs are still poorly understood. The hypothesis of this research is that residence in zip code containing POPs site increases the risk of female breast cancer. The information of breast cancer patients as well as data of waste exposure, economic income and urbanization of residence areas were collected from databases including the New York Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS), etc. The Zip Code was used to characterize the residence area. Negative binomial regression was applied to model the hospital discharge rate of breast cancer for women over 30 years old and the description parameters included exposure, age, ethnicity, income and urbanization. The results showed that there were interactions between the parameters (such as exposure and ethnicity, exposure and income, exposure and urbanization). For some subgroups, as compared to women living in zip code without hazardous waste sites, women living in zip code containing POPs sites had significantly increased discharge rates of breast cancer (rate ratio (RR) 1.10 ~ 1.34, P < 0.05). This relationship was stronger in African American than Caucasian women and stronger in more urbanized areas than in rural areas. After adjustment for the confounders, the hospital discharge rate of breast cancer was significantly associated with residence in zip code containing POPs sites for some women.

persistent organic pollutants; POPs; breast cancer; hospital discharge rate; women; residence

10.7524/AJE.1673-5897.20151214002

国家自然科学基金项目(41471391,41071311,40871214);教育部新世纪优秀人才支持计划项目(NCET-10-0200)

卢晓霞(1972-),女,副教授,研究方向为环境地学,E-mail: luxx@urban.pku.edu.cn

*通讯作者(Corresponding author), E-mail: luxx@urban.pku.edu.cn

2015-12-14 录用日期:2016-01-20

1673-5897(2016)2-201-08

X171.5

A

简介:卢晓霞(1972—),女,环境地学博士,副教授,主要研究方向环境地学,发表学术论文60余篇。

卢晓霞, Lawrence Lessner, David O Carpenter. 妇女乳腺癌医院出院率与在含持久性有机污染物场地邮政区居住之间的关系[J]. 生态毒理学报,2016, 11(2): 201-208

Lu X X, Lessner L, Carpenter D O. Association between hospital discharge rate for female breast cancer and residence in zip code containing persistent organic pollutants [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2016, 11(2): 201-208 (in Chinese)

#共同通讯作者(Co-corresponding author),E-mail: dcarpenter@albany.edu