海洋浮游微食物网对氮、磷营养盐的再生研究综述

张武昌,陈雪,3,李海波,3,赵丽,赵苑,董逸,肖天(1.中国科学院海洋研究所海洋生态和环境科学重点实验室,山东 青岛 266071;2.青岛海洋科学与技术国家实验室海洋生态与环境科学功能实验室,山东 青岛 266071;3.中国科学院大学,北京 100049)

海洋浮游微食物网对氮、磷营养盐的再生研究综述

张武昌1,2,陈雪1,2,3,李海波1,2,3,赵丽1,2,赵苑1,2,董逸1,2,肖天1,2

(1.中国科学院海洋研究所海洋生态和环境科学重点实验室,山东青岛266071;2.青岛海洋科学与技术国家实验室海洋生态与环境科学功能实验室,山东青岛266071;3.中国科学院大学,北京100049)

海洋浮游微食物网包括病毒、细菌、聚球藻蓝细菌、原绿球藻、微微型自养真核生物、微型浮游动物(混合营养和异养鞭毛虫、纤毛虫)等生物类群,其中病毒、细菌及微型浮游动物等异养生物类群是海洋中氮、磷营养盐再生的重要贡献者。海洋中细菌吸收还是释放营养盐取决于细菌与底物中元素的比例,在多数海区,异养细菌都是吸收营养盐。病毒主要通过溶解宿主来释放宿主细胞中的物质,释放的营养元素的存在形态大多为有机物。微型浮游动物对营养盐的再生主要通过排泄来完成,目前在实验室内测定微型浮游动物排泄率的研究比较少,进行研究的主要困难有两个:第一,微型浮游动物的室内培养较难;第二,测定微型浮游动物的代谢率技术难度较高。根据已有研究结果,鞭毛虫的单位体重排氮率为2.8~140 μg N(mg DW)-1h-1,最大排氮率为7.0×10-9~13.8×10-6μg NH4+N cell-1h-1,再生效率为0~100%;最大排磷率为3.8×10-9~6.6×10-7μg P cell-1h-1,再生效率为0~100%。鞭毛虫的营养盐排泄率和再生效率受鞭毛虫自身的生长阶段和生活策略、饵料中元素比例及温度的影响。纤毛虫的单位体重排氮率为0.25~178 μg N(mg DW)-1h-1,最大排氮率为1.59×10-7~ 1.2×10-4μg NH4+N cell-1h-1;单位体重排磷率为13~363 μg P(mg DW)-1h-1,最大排磷率为0~1.3×10-5μg P cell-1h-1。影响纤毛虫排泄率和再生速率的主要因素为纤毛虫生长阶段和温度。自然海区测定微型浮游生物对营养盐的再生的方法主要为同位素稀释法,此外还可以根据其他资料推算微型浮游生物的营养盐再生速率及产生率以反映再生能力。多数野外实验结果证明微型浮游动物是营养盐主要的再生者。

微食物网;微型浮游动物;营养盐再生;排泄

海洋浮游微食物网包括病毒、细菌、聚球藻蓝细菌、原绿球藻、微微型自养真核生物、微型浮游动物(混合营养和异养鞭毛虫、纤毛虫)等生物类群,除聚球藻蓝细菌、原绿球藻和微微型自养真核生物外,其他类群都是异养生物。海洋中的氮、磷等营养盐随生物地球化学循环在生物体和环境间循环。异养生物(含混合营养生物)在生长过程中会将溶解态营养盐释放到海水中,这一过程即为营养盐再生(nutrient regeneration)。海洋浮游微食物网的营养盐再生过程主要是异养生物类群来完成,微型浮游动物对营养盐的再生主要通过排泄(excretion)来完成,细菌对营养盐的再生也被称为再矿化(remineralization) (Glibert et al,1982;Glibert,1982)。营养盐再生效率(R,regeneration efficiency)可以用来衡量生物对营养盐再生的贡献,即在一定时间段内摄食者排出的营养盐(E)和摄入的营养盐(I)的比值(E/I×100%),或者是整个培养时间段内排出的所有的营养盐和培养开始时颗粒态营养盐的比值(Goldman et al,1985b)。

目前国内外在浮游微食物网对营养盐的再生的研究还很少,本文对以往的研究进行综述,以期为此类研究提供借鉴。

1 异养细菌对营养盐的再生

在微食物环概念(Azam et al,1983)提出之前,Johannes(1964 b)就发现海洋异养细菌能够吸收无机磷营养盐。随着微食物环概念的提出,人们逐渐意识到单细胞异养生物(细菌和原生动物)也是大部分营养盐再生的贡献者(Caron,1994)。

海洋中没有被摄食消耗的有机碳被称为碎屑(Fenchel et al,1977),海洋浮游细菌依靠分解海水中的碎屑进行生长和代谢,这些碎屑被称为细菌的底物(substrate)。碎屑的化学组成变化很大,如大型海藻和海草的残体是一类高分子量、结构复杂的惰性碳化合物碎屑,而海洋浮游生物排出的单糖、氨基酸等则是极易被氧化的溶解性碎屑。在大洋中,细菌的主要底物是后者。传统观点认为细菌利用这些溶解和颗粒碎屑物质并向海水中释放氮、磷元素。但是在20世纪80年代,很多研究表明这些异养浮游细菌可以吸收海水中的无机氮、磷营养盐,与浮游植物是竞争关系(Kirchman,1994;Wheeler et al,1986)。

Caron(1994)指出细菌是吸收还是释放营养盐取决于细菌和底物的元素比例。当底物的C∶N比例远高于细菌C∶N含量时,底物中氮营养盐缺乏,细菌就主要是吸收海水中的氮营养盐;反之细菌就主要向海水中释放氮营养盐。例如,Goldman等(1987 a)利用不同CN(1.5∶1到10∶1)的底物喂养细菌研究氮元素的再生效率,细菌的C∶N比值为5∶1,当底物的C∶N比值为10∶1时,底物中氮营养盐缺乏,细菌吸收海水中的氮营养盐,因此氮的再生效率(RN)为0%;当底物的C∶N比值为1.5∶1时,细菌释放氮营养盐,RN为86%。虽然至今仍不能确定浮游异养细菌的底物的化学组成,但是一般认为海洋中碳水化合物是细菌生长和代谢的主要底物,其C∶N可能大于10∶1;而细菌的核酸含量较高,N元素含量较高,在生长率较高的时候,细菌的C∶N含量可低至4∶1。所以海洋中快速生长的细菌主要吸收海水中的氮营养盐,不太可能是引起氮再生的主要生物类群。

在海洋中,细菌的底物中溶解有机碳归根结底来自浮游植物。由于底物中的C∶N比值是细菌是否吸收无机营养盐的因素,Kirchman(1994)提出假说:在寡营养海区,浮游植物缺乏氮营养盐,形成的底物C∶N比值较高,因此,细菌会从海水中吸收更多无机营养盐;在近岸富营养海区,浮游植物产生的底物C∶N比值较低,细菌能从底物中获得足够的氮营养盐,对海水中无机氮营养盐的吸收会较少。同理,在层化较好的水体中,真光层中营养盐较缺乏,浮游植物产生的底物C∶N比值较高,细菌会吸收海水中的无机营养盐;而在真光层以下,营养盐丰富,浮游植物产生的底物C∶N比值低,细菌很可能是营养盐的再生者(Caron,1994)。

此后的研究在以上假说的基础上进行了细化研究,在近岸河口等富营养海区也发现异养细菌吸收营养盐,不过是有机形态的营养盐(王秋璐等,2010;白洁等,2005)。因此目前普遍认为异养细菌在多数海区都吸收营养盐,海洋浮游原生动物才是营养盐再生的主要贡献者。

2 病毒对营养盐的再生

海洋浮游病毒会导致浮游细菌和浮游植物死亡,在有些情况下病毒导致的死亡率甚至会大于被摄食导致的死亡率。病毒感染宿主,导致宿主溶解,宿主细胞中的物质释放到周围海水中,营养元素的存在形态大多为有机物的形态,这一点不同于浮游动物排泄的营养盐,因此这一过程又被称为再活化(remobilization) (Wilhelm et al,2000)。

到目前为止,直接测量病毒对营养盐的再活化是非常困难的。在实验室内,研究在病毒和宿主培养体系中用放射性标记法研究病毒感染对营养元素的释放,发现病毒感染单胞藻 Aureococcus anophagefferens后,在培养体系中没有发现溶解态的有机氮营养盐,可能说明释放的有机氮营养盐很快被细菌分解利用(Gobler et al,1997)。

因为直接测定比较困难,间接估计病毒对营养元素再活化是另一种选择。间接估计的方法估计病毒通过溶解细菌释放到水体中的营养盐,需要的参数包括病毒的周转率和裂解量、细菌的死亡率和生长率、细菌的元素含量等。利用这种方法,Wilhelm等(2000)估计墨西哥湾病毒对氮营养盐的再活化速率为0.02~1.0μgL-1d-1,佐治亚海峡病毒对氮、磷和铁营养盐的再活化速率分别为0.25~1.98 μg L-1d-1,0.02~0.18 μg L-1d-1和0.05~0.17 μg L-1d-1。

除了病毒杀死细菌释放营养盐外,病毒自身死亡导致的营养盐释放正在引起关注(Thomas et al,1999;Jover et al,2014)。在自然条件下,病毒衰亡会释放其体内的营养元素。病毒颗粒与其宿主相比,磷元素的含量较高,因此,与氮元素相比,病毒衰亡对海洋磷循环的重要性要更大(Jover et al,2014)。

3 微型浮游动物对营养盐的再生

在测定微型浮游动物的排泄率的研究开展之前,Johannes(1964a) 就以磷循环为例首次指出研究微型浮游动物对营养盐的再生的重要性。浮游动物代谢释放的营养盐是海洋浮游植物生长所需营养盐的重要来源。Johannes(1964a)用等体重代谢时间(Body-weightEquivalentExcretionTime,BEET),即动物排出等同于自身体内所含营养盐总量的营养盐所需的时间,来衡量不同粒级的生物的代谢率的快慢。根据当时已有的资料,确立了几种浮游动物排泄磷的BEET与动物体重的关系。动物的体重越小,单位体重的代谢率越高,BEET越短。根据这些数据的关系,推论出体重为2.5×10-7μg dry wt(体积为1 μ3)的鞭毛虫,其BEET为2 min。微型浮游动物在浮游动物生物量中占的比例比中型浮游动物大,因此微型浮游动物的代谢对营养盐的再生的作用比中型浮游动物大。

目前对微型浮游动物的营养盐再生研究主要集中在两个方面:针对微型浮游动物的某一种类,研究其对营养盐的排泄率(excretion rates);针对某一海区的所有微型浮游动物,研究其对营养盐的再生速率(regeneration rates)。

3.1实验室内测定微型浮游动物的排泄率

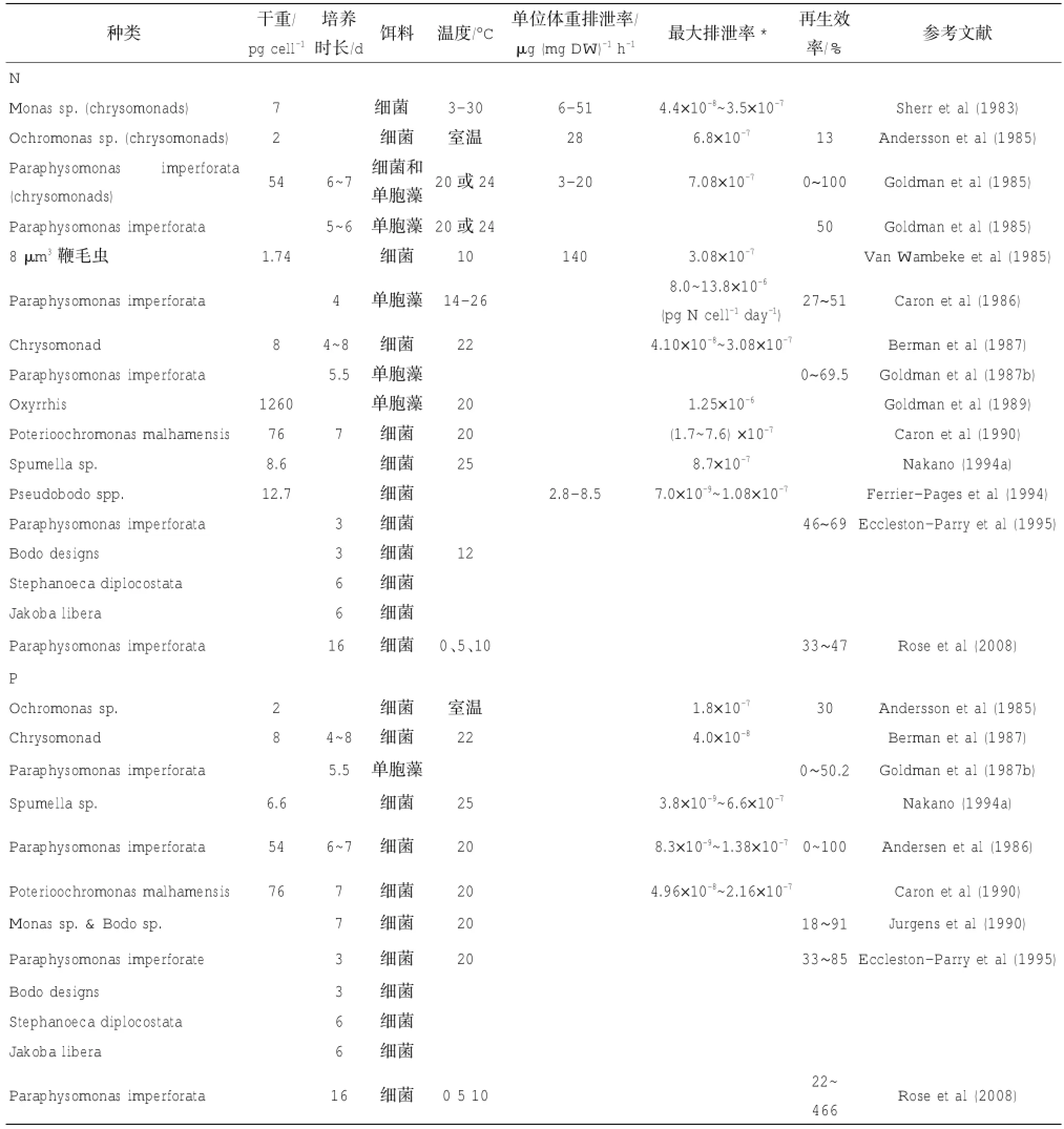

测定微型浮游动物对营养盐的排泄率主要在实验室内进行,此类研究比较少(表1,表2)。目前进行研究的主要困难有两个。第一,微型浮游动物的室内培养较难。第二,测定微型浮游动物的代谢率技术难度较高。由于微型浮游动物个体微小,虽然单位体重的代谢率较高,但个体的代谢率却很小,要克服单个个体代谢率低的困难,就要加长培养时间(例如Goldman等(1985 b)培养7 d),为了在培养时间内使动物保持好的状态,就要投喂浮游植物、细菌等作为饵料,这时就产生了饵料吸收浮游动物释放的营养盐的问题。目前主要有两种方法消除投喂饵料对营养盐的影响:第一种培养在持续黑暗的条件下进行,从而避免饵料浮游植物在培养过程中吸收营养盐;第二种方法是设立对照组,估计饵料对营养盐的吸收率。除此之外,Eccleston-Parry等(1995)用细菌为饵料测定鞭毛虫的营养盐再生作用时,用细菌抑制剂阻止细菌生长,以消除细菌对营养盐的影响。

表1 实验室内测定海洋鞭毛虫的营养盐排泄率

异养原生动物排泄物中,NH4+和PO4-是营养盐的主要存在形式,还有溶解有机氮(DON)和溶解有机磷(DOP),其中溶解有机氮主要有氨基酸、多肽、尿素、尿酸、次黄嘌呤、二氢尿嘧啶、腺嘌呤、鸟嘌呤等。这些溶解有机营养盐也很重要,但是其绝对量比无机营养盐要小,例如尿素在稳定生长期开始排放,大约占总排放量的15%(Goldman et al,1985b),Bidigare(1983)的研究结果表明氨基酸只占总氮排放的10%~15%,Andersson等(1985)和Goldman等(1985b)在其研究中则发现氨基酸占比更少,只有0.02%。由于和无机磷酸盐(等)是原生动物排泄的主要形式,本文仅介绍和无机磷酸盐(等)的排泄率。

3.1.1鞭毛虫的营养盐排泄率

表2 实验室内测定海洋纤毛虫的营养盐排泄率

Goldman等(1985b)在将浮游植物、细菌单独培养时和两者混合培养时,培养液中非常少;当培养液中加入以浮游植物、细菌为饵料的异养鞭毛虫Paraphysomonas imperforata时,培养液中的含量很高,这说明鞭毛虫是再生的主要贡献者,细菌的贡献可以忽略。

到目前为止,已经测定9种鞭毛虫的排氮率,9种鞭毛虫的排磷率。根据这些研究,鞭毛虫的单位体重排氮率为2.8~40 μg N(mg DW)-1h-1,最大排氮率为7.0×10-9~13.8×10-6μgN cell-1h-1,再生效率为0~100%。最大排磷率为3.8×10-9~6.6× 10-7μg P cell-1h-1,再生效率为0~100%(表1)。

鞭毛虫的排氨率和再生效率在培养的不同时期不同。在饵料的生长不受营养盐限制的条件下,鞭毛虫P.imperforata的排氨率在指数生长期最高,在进入稳定生长期后明显变小;再生效率在指数生长期最低(15%~30%),当饵料生物受到氮限制时,鞭毛虫的氮再生效率降为8% (Goldman et al,1985b)。

鞭毛虫P.imperforata在摄食浮游植物时,浮游植物的N∶P含量对鞭毛虫进行氮再生和磷再生有影响。饵料中氮缺乏越严重,鞭毛虫再生的滞后期越长,甚至到稳定生长期才有再生;在饵料中磷缺乏的情况下,的排出在指数生长期即开始,直到稳定生长期后还有排出。当饵料中缺乏氮时,鞭毛虫在整个生长周期中都有磷的排泄,且排泄速度大体相同;当饵料中缺乏磷时,磷的排泄在鞭毛虫的任何生长期都没有发生(Goldman et al,1987)。

Eccleston-Parry等(1995)发现除了饵料中N: P之外,不同生活策略的鞭毛虫的营养盐再生效率不同。以4种鞭毛虫P.imperforata、Bodo designs、Jakobalibera和Stephanoecadiplocostata为例,前两者是高生长率(分别为0.2和0.14 h-1)的鞭毛虫,后两者为低生长率的鞭毛虫(分别为0.029和0.026 h-1)。这4种鞭毛虫对氮的再生效率相差不大(46%~69%),但是对磷的再生效率有明显差异,高生长率鞭毛虫为63%~85%,而低生长率鞭毛虫为33~35%。

大多数实验研究的温度都比较温和,处于15℃~ 25℃的范围。Sherr等(1983)的实验温度为3℃~ 30℃,研究发现鞭毛虫Monas sp.在18~23.5℃的排氨率较低,而在低温和高温时排氨率明显提高。这种变化可能是鞭毛虫在低温和高温处于生理不适应状态造成的。从南极海域分离的P.imperforata在0~10℃的温度范围内生长率随温度升高而明显升高,但是温度的变化对氮和磷的再生没有明显影响(Rose et al,2008)。

3.1.2纤毛虫的营养盐排泄率

表2列举了几种纤毛虫的营养盐排泄率,其中真正属于浮游类群的只有 Codonella、Colpidium、Stokesia、Strombidium和Tintinnopsis,因为浮游类群太少,表2也列出了一些底栖类群的数据以供比较。这些研究表明纤毛虫单位体重排氮率为0.25~ 178 μg N(mg DW)-1h-1,最大排氮率为1.59×10-7~ 1.2×10-4μg NH4+N cell-1h-1;单位体重排磷率为13~363 μg P(mg DW)-1h-1,最大排磷率为0~ 1.3×10-5μg P cell-1h-1。

纤毛虫的营养盐排泄率和再生效率在培养的不同时期不同。排氨率在指数生长期一般比较高,Ferrier-Pages等(1994) 用活的细菌喂养无壳纤毛虫(Strombidiumsulcatum)时,排氨率在指数生长期一直保持高值,进入稳定生长期时迅速降低。再生效率在指数生长前期一直较低(<30%),在指数生长期后期开始升高(>100%),稳定生长期保持高值(30%~100%) (Ferrier-Pages et al,1994)。Allali等(1994)用同种无壳纤毛虫研究了纤毛虫的排磷率,在培养实验刚开始的停滞期排磷率最高(13±12×10-6μg P cell-1h-1),随后降低,到稳定生长后期为0 μg P cell-1h-1。

温度对纤毛虫的营养盐排泄率有一定影响。Verity(1985) 研究了两种近岸砂壳纤毛虫(Tintinnopsis acuminata,T.vasculum)的排氮率,发现这两种砂壳纤毛虫的营养盐排泄率随温度升高而升高,T.acuminata的营养盐排泄率在15℃时为0.05 h-1,温度为25℃时上升至0.12~0.14 h-1;T. vasculum的营养盐排泄率在5℃时为0.01~0.02 h-l,温度为15℃时上升为0.05~0.06 h-1。

3.1.3最大营养盐排泄率和干重的关系

Dolan(1997)根据当时已有的实验室内测定的原生动物排泄率资料,用氮和磷的最大排泄率(Excr,μg cell-1h-1)和干重(DW,mg cell-1)进行回归,得出两者的关系:

Log Excr N=-1.388+0.622 log DW

(n=15,r=0.899)

Log Excr P=-2.101+0.570 log DW

(n=12,r=0.847)

根据上述等式,原生动物最大的单位体重排磷率高于通过后生动物“体长-排泄率”关系外推得出的数值(Ikeda et al,1982;Wen et al,1994;Hargrave et al,1968;Mullin et al,1975),而最大的单位体重排氮率接近通过后生动物“体长-排泄率”关系外推得出的数值(Ikeda et al,1982;Verity,1985; Vidal et al,1982; Mullin et al,1975),表明原生动物对磷再生的作用可能高于对于氮再生的作用。

3.2自然海区测定微型浮游动物对营养盐的再生

在自然海区进行的研究,多以粒径级划分生物类群,通常很难将细菌、浮游植物和浮游动物严格划分出来。本节讨论的研究对象微型浮游生物中的主要类群为微型浮游动物,因此这些研究结果主要反映了微型浮游动物的营养盐再生能力。

3.2.1测定微型浮游动物对营养盐的再生的方法

同位素稀释法是测定微型浮游动物对营养盐的再生速率的方法之一,这种方法最初用于土壤生境的研究中,Alexander(1970)将这种方法用于湖泊研究中,随后,Harrison(1978),Caperon等(1979),Glibert(1982),Paasche等(1982)将这种方法用于海洋中。

同位素稀释法的原理如下:海水中的微型浮游动物吸收氮营养盐,同时也在排放出氮营养盐,如果在海水中加入15N同位素标记的氮营养盐进行培养,在培养过程中,假设浮游生物对15N和14N的吸收没有差别,即对海水中15N和14N按照海水中的原子比例进行吸收,而吸收的15N并没有排出到海水中,因此海水中氮营养盐的15N所占的比例会变小。通过测量海水中氮营养盐15N和14N的原子比例的变化(一般是变小,这种方法也因此被称为同位素稀释法(isotope dilution technique) Caperon et al,1979),就可以估计氮营养盐的吸收速率和再生效率(Glibert et al,1982)。用同位素稀释法也可以同时得出浮游动物对氨、尿素等氮营养盐的吸收速率和再生速率(μg atoms L-1h-1),Caperon等(1979)给出了计算公式,Glibert等(1982)和Laws(1984)对这个方法的理论和操作进行了完善。此方法也可以用于磷再生速率的测定,Harrison(1983)利用33P同位素稀释技术计算了磷的再生速率。

除了直接测定外,也可以根据其他参数推算微型浮游动物的营养盐再生速率。Sorokin(1985)根据微型浮游动物生物量、呼吸率和P∶C(1.4%)来估计磷的再生速率。Sorokin(2002)和Sorokin等(2008)则是利用环境中磷浓度的变化率和吸收率计算磷再生速率。此外,Caron等(1988)根据C和N的代谢模型,用微型浮游动物的摄食率来估计其营养盐产生率,以此来反映其对营养盐的再生能力。Landry(1993)对这个模型进行了改进:

EN=(AEN×IC×N:CPP)-(IC×GGEC×N:CMZ)

其中:EN是N排泄率(μg N L-1d-1),AEN是微型浮游动物对N的同化效率,IC是微型浮游动物对C的摄食率,N∶CPP和N∶CMZ分别是饵料浮游植物和微型浮游动物体内N和C的比值,GGEC是微型浮游动物摄食碳的毛生长率。Lehrter等(1999),曾祥波等(2007)使用这个方法估计微型浮游动物对营养盐的产生率。

3.2.2自然海区微型浮游生物对NH4+的再生

多数野外实验结果验证了Johannes(1964a)提出的微型浮游动物是营养盐主要的再生者的假说(表3)。在加利福尼亚沿岸,大于90%的再生的NH4+来自微型浮游生物 (粒级小于 183 μm)(Harrison,1978)。在夏威夷卡内奥赫湾(Kaneohe Bay),微型浮游动物排泄的NH4+是大型浮游动物的30~40倍,主要的排泄者粒级小于 35 μm (Caperon et al,1979)。在上升流区,大于95%的NH4+再生是由粒级小于15 μm的浮游生物贡献的(Probyn,1987)。在英吉利海峡,粒级为1~15 μm的生物对营养盐的再生速率全年都大于粒级为15~ 200 μm和粒级小于1 μm的生物(Le Corre et al,1996)。在挪威奥斯陆峡湾,粒级为45~200 μm的微型浮游生物是最主要的营养盐再生者(Paasche et al,1982)。例如在切萨皮克湾(Glibert et al,1992),粒级小于10 μm的生物对NH4+的再生速率远远大于粒级超过200 μm的生物。在密西西比河羽流区也出现类似的情况(Jochem et al,2004)。

表3 自然海区微型浮游生物对NH4+的再生速率

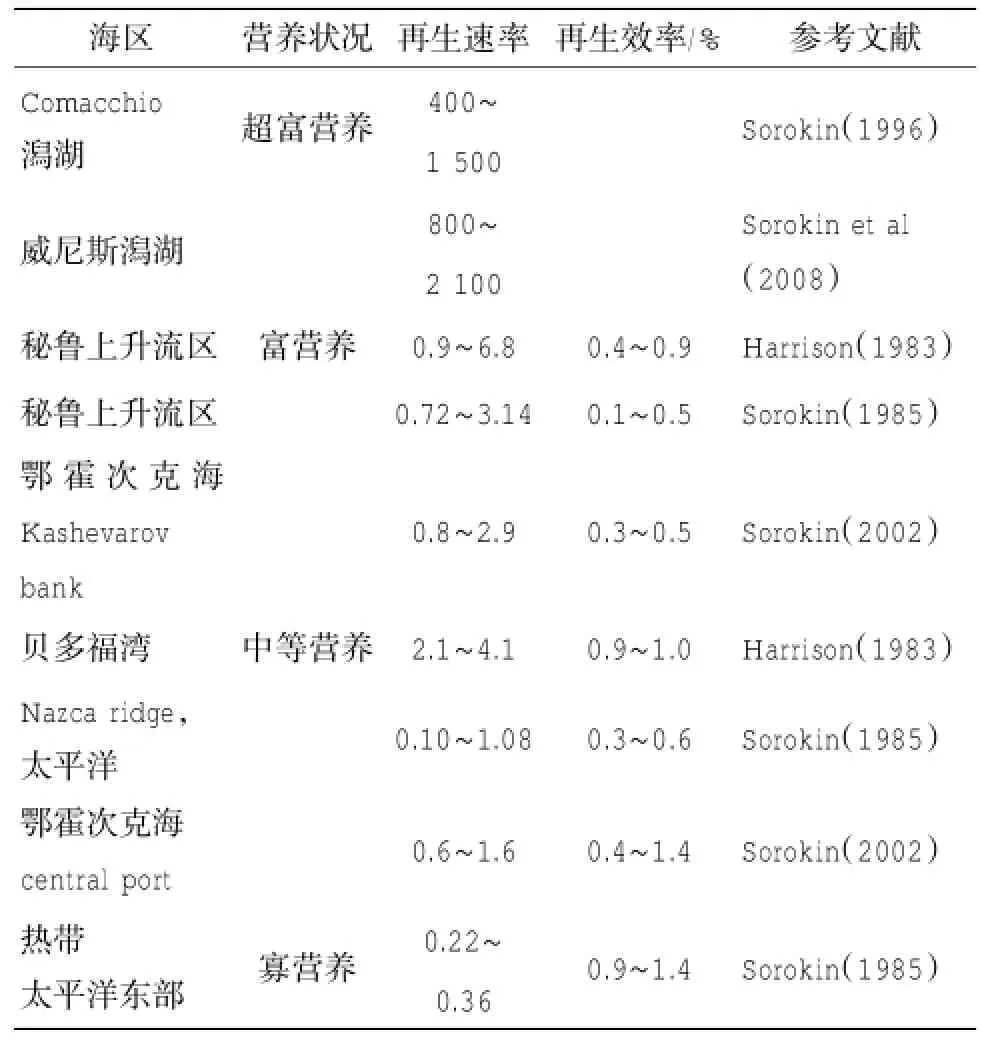

表4 自然海区微型浮游生物对磷的再生速率 (μg P L-1d-1)

在添加不同丰度(最大丰度20 L-1)桡足类的实验中,再生速率在桡足类丰度达到一定数值时达到最大,然后随着添加桡足类丰度的增加而降低(Glibert et al,1992)。这些现象说明,浮游动物各个营养级之间的摄食作用对的再生有影响。

3.2.3自然海区微型浮游动物对尿素的再生

微型浮游动物对尿素的再生可以用15N同位素稀释法进行测定(Slawyk et al,1990)。在切萨皮克湾,尿素的再生速率为0.42~2.58 μg N L-1h-1,尿素的再生速率一直大于吸收速率(Lomas et al,2002)。在英吉利海峡,粒级小于200 μm的浮游生物对尿素的再生速率为0.6~20.6 nmol N L-1h-1,nano级和micro-级浮游生物再生尿素分别为51% 和36%,pico级的再生尿素很低,只在4月和10月才能测到;再生速率在冬季最低,夏季最高;再生和吸收速率的比值在不同的季节和水层都接近1,说明异养生物再生的尿素几乎完全被浮游植物吸收;在周年内,再生尿素占再生氮(和尿素)的33%(L’Helguen et al,2005)。

3.2.4自然海区微型浮游动物对磷的再生

目前在自然海区进行微型浮游动物对磷的代谢的研究较少,多数研究内容是微型浮游生物对磷的吸收速率(Sorokin,1985;Sorokin et al,1996)。磷的再生速率变化范围很大(0.02~2100 μg P L-1d-1),富营养化程度越高,再生速率越高(表4)。再生速率和吸收速率的比值为0.1~1.4,总体来说再生和被吸收保持平衡(Sorokin et al,2008)。

4 总结

目前,科学界普遍认为海洋浮游微食物网在海洋水体营养盐的再生中起到重要作用,其中主要的贡献者为异养生物类群(异养细菌,病毒,微型浮游动物等)。海洋中细菌吸收还是释放营养盐取决于细菌与底物中元素的比例,在多数海区,异养细菌都是吸收营养盐。病毒主要通过溶解宿主来释放宿主细胞中的物质,释放的营养元素的存在形态大多为有机物。微型浮游动物对营养盐的再生主要通过排泄来完成,但是微型浮游动物的营养盐再生速率测定还较少,主要是因为技术难度较大。微型浮游动物自身的生长阶段和生活策略、饵料中元素比例及温度等环境因子是影响微型浮游动物排泄率和再生速率的主要因素。自然海区测定微型浮游生物对营养盐的再生的方法主要为同位素稀释法,还可以根据其他资料推算微型浮游生物的排泄率。多数野外实验结果证明微型浮游动物是营养盐主要的再生者。我国的微型浮游动物生态学研究才刚刚起步,只在台湾海峡估计了营养盐的再生(曾祥波等,2007)。

Alexander V,1970.Relationships between turnover rates in the biological nitrogen cycle and algal productivity,37-50,in Dynamics of the nitrogen cycle in lakes.Institute of Marine Science,University of Alaska.

Allali K,Dolan J R,Rassoulzadegan F,1994.Culture characteristics and orthophosphate excretion of a marine oligotrich ciliate,Strombidium sulcatum,fed heat-killed bacteria.Marine Ecology Progress Series, 105:159-165.

Andersen O K,Goldman J C,Caron D A,et al,1986.Nutrient cycling in a microflagellate food chain:III.Phosphorus dynamics.Marine Ecology Progress Series,31:47-55.

Andersson A,Lee C,Azam F,et al,1985.Release of amino acids and inorganic nutrients by heterotrophic marine microflagellates.Marine Ecology Progress Series,23(1):99-106.

Azam F,Fenchel T,Field J G,et al,1983.The ecological role of watercolumn microbes in the sea.Marine Ecology Progress Series,10 (3):257-263.

Berman T,Nawrocki M,Taylor G T,et al,1987.Nutrient flux between bacteria,bacterivorous nanoplantonic protists and algae.Marine Microbial Food Webs,2(2):69-82.

Bidigare R R,1983.Nitrogen excretion by marine zooplankton.In Carpenter EJ and Capone DG(ed)Nitrogen in the marine environment.New York:Academic Press,385-409.

Bode A,Dortch Q,1996.Uptake and regeneration of inorganic nitrogen in coastal waters influenced by the Mississippi River:Spatial and seasonal variations.Journal of Plankton Research,18(12) :2251-2268.

Caperon J,Schell D,Hirota J,et al,1979.Ammonium excretion rates in Kaneohe Bay,Hawaii,measured by a15N isotope dilution technique. Marine Biology,54(1):33-40.

Caron D A,Goldman J C,1988.Dynamics of protistan carbon and nutrient cycling.Journal of Protozoology,35(2):247-249.

Caron D A,Goldman J C,Dennett M R,1986.Effect of temperature on growth,respiration,and nutrient regeneration by an omnivorous microflagellate.Applied and Environmental Microbiology,52(6): 1340-1347.

Caron D A,Porter K G,Sanders R W,1990.Carbon,nitrogen and phosphorusbudgetsforthemixotrophicphytopflagellatePoterioochromonas malhamensis(Chrysophyceae)during bacterial ingestion.Limnology and Oceanography,35(2):433-443.

Caron D A.1994.Inorganic nutrients,bacteria,and the microbial loop. Microbial Ecology,28(2):295-298.

Dolan J R,1997.Phosphorus and ammonia excretion by planktonic protists.Marine Geology,139(1):109-122.

Eccleston Parry J D,Leadbeater B S C.1995.Regeneration of phosphorus and nitrogen by four species of heterotrophic nanoflagellates feeding on three nutritional states of a single bacterial strain.Applied and Environmental Microbiology,61(3):1033-1038.

Fenchel T,Jorgensen B B,1977.Detritus food chains of aquatic ecosystems:the role of bacteria.Advances in Microbial Ecology,1:1-49.

Ferrier PagesC,RassoulzadeganF,1994.N remineralization in planktonic protozoa.Limnology and Oceanography,39(2):411-419.

Gardner W S,Cavaletto J F,Cotner J B,et al,1997.Effects of natural light on nitrogen cycling rates in the Mississippi River Plume.Limnology and Oceanography,42(2):273-281.

Gardner W S,Cotner J B,Herche L,1993.Chromatographic measurement of nitrogen mineralization rates in marine coastal waters with15N. Marine Ecology Progress Series,93:65-73.

Gast V,Horstman U,1983.N-remineralization of phyto-and bacterioplankton by the marine ciliate Euplotes vannus.Marine Ecology Progress Series,13:55-60.

Glibert P M,1982.Regional studies of daily,seasonal and size fraction variability in ammonium remineralization.Marine Biology,70(2): 209-222.

Glibert P M,Lipschultz F,McCarthy J J,et al,1982.Isotope dilution models of uptake and remineralization of ammonium by phytoplankton.Limnology and Oceanography,27(4):639-650.

Glibert P M,Miller C A,Garside C,1992.regeneration and grazinginterdependent processes in size-fractionatedexperiments. Marine Ecology Progress Series,82(2):65-74.

Gobler C J,Hutchins D A,Fisher N S,et al,1997.Release and bioavail-ability of elements following viral lysis of a marine chrysophyte. Limnology and Oceanography,42(7):1492-1504.

Goldman J C,Caron D A,Andersen O K,et al.1985 b.Nutrient cycling in a microflagellate food chain:I.Nitrogen dynamics.Marine Ecology Progress Series,24(3):231-242.

Goldman J C,Caron D A,Dennett M R,1987 a.Regulation of gross growth efficiency and ammonium regeneration in bacteria by substrate C:N ratio.Limnology and Oceanography,32(6):1239-1252.

Goldman J C,Caron D A,Dennett M R,1987b.Nutrient cycling in a microflagellatefoodchain:IVphytoplankton-microflagellate interactions.Marine Ecology Progress Series,38:75-87.

Goldman J C,Caron D A.1985 a.Experimental studies on an omnivorous microflagellate:implications for grazing and nutrient regeneration in the marine microbial food chain.Deep-Sea Research,32:899-915.

Goldman J C,Dennett M R,Gordin H,1989.Dynamics of herbivorous grazing by the heterotrophic dinoflagellate Oxyrrhis marina.Journal of Plankton Research,11(2):391-407.

Hargrave B T,Geen G H,1968.Phosphorus excretion by zooplankton. Limnology and oceanography,13(2):332-342.

HarrisonWG,1978.Experimentalmeasurementsofnitrogen remineralization in coastal waters.Limnology and Oceanography,23 (4):684-694.

Harrison W G,1980.Nutrient regeneration and primary production in the sea.In Primary Productivity in the sea.New York:Falkowski GP ed Plenum Press.

Harrison W G,1983.Uptake and recycling of soluble reactive phosphorus by marine microplankton.Marine Ecology Progress Series,10:127-135.

Harrison W G,Douglas D,Falkowski R,et al,1983.Summer nutrient dynamics of the Middle Atlantic Bight:nitrogen uptake and regeneration.Journal of Plankton Research,5(4):539-556.

Ikeda T,Hing Fay E,Hutchinson S A,et al,1982.Ammonia and inorganic phosphate excretion by zooplankton from inshore waters of the great barrier reef,Queensland.I.relationship between excretion rates and body size.Australian Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research,33(1):55-70.

Jochem F J,McCarthy M J,Gardner W S,2004.Microbial ammonium cycling in the Mississippi River plume during the drought spring of 2000.Journal of Plankton Research,26(11):1265-1275.

Johannes R E,1964a.Phosphorus excretion and body size in marine animals:microzooplankton and nutrient regeneration.Science,146 (3646):923-924.

Johannes R E,1964b.Uptake and release of dissolved organic phosphorus by representatives of a coastal marine ecosystem.Limnology and Oceanography,9(2):224-234.

Jover L F,Effler T C,Buchan A,et al,2014.The elemental composition of virus particles:implications for marine biogeochemical cycles. Nature Reviews Microbiology,12(7):519-528.

Jurgens K,Gude H,1990.Incorporation and release of phosphorus by planktonic bacteria and phagotrophic flagellates.Marine Ecology Progress Series,59:271-284.

Kirchman D L,1994.The uptake of inorganic nutrients by heterotrophic bacteria.Microbial Ecology,28(2):255-271.

L'Helguen S,Slawyk G,Corre P L,2005.Seasonal patterns of urea regeneration by size-fractionated microheterotrophs in well-mixed temperate coastal waters.Journal of Plankton Research,27(3):263-270.

La Roche J,1983.Ammonium regeneration:its contribution to phytoplankton nitrogen requirements in a eutrophic environment.Marine Biology,75(2-3):231-240.

Landry M R,1993.Predicting excretion rates of microzooplankton from carbon metabolism and elemental ratios.Limnology and Oceanography,38(2):468-472.

Laws E A,1984.Isotope dilution models and the mystery of the vanishing15N.Limnology and Oceanography,29(2):379-386.

Le Corre P,Wafar M,L'Helguen S,et al,1996.Ammonium assimilation and regeneration by size-fractionated plankton in permanently well-mixed temperate waters.Journal of Plankton Research,18: 355-370.

Lehrter J C,Pennock J R,McManus G B,1999.Microzooplankton grazing and nitrogen excretion across a surface estuarine-coastal interface. Estuaries,22(1):113-125.

Lomas M W,Trice T M,Glibert P M,et al,2002.Temporal and spatial dynamics of urea uptake and regeneration rates and concentrations in Chesapeake Bay.Estuaries,25:469-482.

Mullin M M,Perry M J,Renger E H,et al,1975.Phosphorus excretion by zooplankton:a comparison of methods.Marine Sciences Communication,1:1-13.

Nakano S I,1994 a.Carbon:nitrogen:phosphorus ratios and nutrient regeneration of a heterotrophic flagellate fed on bacteria with different element ratios.Archiv fuer Hydrobiologie,129(3):257-271.

Nakano S I.1994.Rates and ratios of nitrogen and phosphorus released by a bacterivorous flagellate.Japanese Journal of Limnology,55 (2):115-123.

Paasche E,Kristiansen S,1982.Ammonium regeneration by microzooplankton in the Oslo fjord.Marine Biology,69(1):55-63.

Probyn T A,1987.Ammonium regeneration by microplankton in an upwelling environment.Marine Ecology Progress Series,37(5):53-64.

Rose J,Vora N M,Caron D A,2008.Effect of temperature and prey type on nutrient regeneration by an Antarctic bacterivorous protist.Microbial Ecology,56(1):101-111.

Sherr B F,Sherr E B,Berman T,1983.Grazing,growth and ammonium excretion rates of a heterotrophic microflagellate fed with four species of bacteria.Applied and Environmental Microbiology,45 (4):1196-1201.

Slawyk G,Raimbault P,L'Helguen S,1990.Recovery of urea nitrogen from seawater for measurement of15N abundance in urea regeneration studies,using the isotope-dilution approach.Marine Chemistry,30:343-362.

Sorokin Y I,1985.Phosphorus metabolism in planktonic communities of the Eastern Tropical Pacific.Marine Ecology Progress Series,27 (14):87-97.

Sorokin Y I,2002.Dynamics of inorganic phosphorus in pelagic communities of the Sea of Okhotsk.Journal of Plankton Research,24 (12):1253-1263.

Sorokin Y I,Dallocchio F,2008.Dynamics of phosphorus in the Venice lagoon during a picocyanobacteria bloom.Journal of Plankton Research,30(9):1019-1026.

Sorokin Y I,Dallocchio F,Gelli F,et al,1996.Phosphorus metabolism in anthropogenically transformed lagoon ecosystems:Comacchio lagoons.Journal of Sea Research,35:243-250.

Taylor W D,1984.Phosphorus flux through epilimnetic zooplankton from Lake Ontario:relationship with body size and significance to phytoplankton.Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences,41: 1702-1712.

Taylor W D.1986.The effect of grazing by a ciliated protozoan on phosphorus limitation of heterotrophic bacteria in batch culture.The Journal of protozoology,33:47-52.

Thomas H,Ittekkot V,Osterroht C,et al,1999.Preferential recycling of nutrients-the ocean's way to increase new production and to pass nutrient limitationLimnology and Oceanography,44(8):1999-2004.

Varela M M,Barguero S,Bode A,et al,2003.Microplanktonic regeneration of ammonium and dissolved organic nitrogen in the upwelling area of the NW of Spain:relationships with dissolved organic carbon production and phytoplankton size-structure.Journal of Plankton Research,25:719-736.

Verity P G,1985.Grazing,respiration,excretion and growth rates of tintinnids.Limnology and Oceanography,30:1268-1282.

Vidal J,Whitledge T E,1982.Rates of metabolism of planktonic crustaceans as related to body weight and temperature of habitat.Journal of Plankton Research,4(1):77-84.

Wen Y H,Vézina A,Peters R H,1994.Phosphorus fluxes in limnetic cladocerans:coupling of allometry and compartmental analysis. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences,51(5): 1055-1064.

Wheeler P A,Kirchman D L,1986.Utilization of inorganic and organic nitrogen by bacteria in marine systems.Limnology and Oceanography,31:998-1009.

Wilhelm S W,Suttle C A,2000.Viruses as regulators of nutrient cycles in aquatic environments.Microbial Biosystems:New Frontiers.551-556.

Wilhelm S W,Suttle C A.Viruses as regulators of nutrient cycles in aquatic environments.Microbial biosystems:New frontiers,edited by:Bell C R,Brylinsky M,and Johnson-Green P,Atlantic Canada Society of Microbial Ecology,2000:551-556.

白洁,李岿然,张昊飞,2005.胶州湾异养浮游细菌对磷的吸收作用及影响因素研究.中国海洋大学学报,自然科学版,35:835-838.

王秋璐,周燕遐,王江涛,等,2010.海洋异养细菌对无机氮吸收的研究.海洋通报,29:231-234,240.

曾祥波,黄邦钦,2007.台湾海峡微型浮游动物的摄食压力及其对营养盐再生的贡献.厦门大学学报,46:231-235.

(本文编辑:袁泽轶)

Review of nutrient(nitrogen and phosphorus)regeneration in the marine pelagic microbial food web

ZHANG Wu-chang1,2,CHEN Xue1,2,3,LI Hai-bo1,2,3,ZHAO Li1,2,ZHAO Yuan1,2,DONG Yi1,2,XIAO Tian1,2

(1.Key Laboratory of Marine Ecology and Environmental Sciences,Institute of Oceanology,Chinese Academy of Sciences,Qingdao 266071, China;2.Laboratory for Marine Ecology and Environmental Science,Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao266071,China;2.University of Chinese Academyof Sciences,Beijing 100049,China)

Marine planktonic microbial food web mainly includes viruses,bacteria,Synechococcus,Prochlorococcus, picoeukaryotes and microzooplankton(heterotrophic and pigmented nanoflagellates and ciliates).The heterotrophic taxonomic groups(including viruses,bacteria and microzooplankton)play an important role in nitrogen and phosphorus regeneration.In the sea,whether bacteria absorb or release nutrients depends on the element ratio of C:N or C:P in substrates.Most results indicate that heterotrophic bacteria absorb nutrients in the most area.Virus releases the nutrient elements mainly by dissolving the host cells.Excretion was the primary way for microzooplankton to regenerate the nutrients. However,only a few studies measuring the excretion rate of microzooplankton have been carried out in the laboratory due to the difficulties in(1)cultivation of marine microzooplankton in the lab,and(2)the determination of the microzooplanktonmetabolic rates.According to the previous research,the weight-specific nitrogen regeneration of nanoflagellates ranged from 2.8 to 140 μg N(mg DW)-1h-1.The maximum nitrogen excretion ranged from 7.0×10-9to 13.8×10-6μg NH4+N cell-1h-1.The rangeofregenerationrateswas0~100%.The maximumphosphorusexcretion ranged from3.8×10-9to6.6×10-7μgPcell-1h-1.The range of regeneration rates was 0~100%.The excretion rate and regeneration rate were influenced by growth phase and living strategy of nanoflagellates,the ratio of the elements in the prey and temperature,etc.In the case of ciliates,the weightspecific nitrogen regeneration ranged from 0.25 to 178 μg N(mg DW)-1h-1.The maximum nitrogen excretion ranged from 1.59×10-7to 1.2×10-4μg NH4+N cell-1h-1.The weight-specific phosphorus regeneration of ciliates ranged from 13 to 363 μg P(mg DW)-1h-1.The maximum phosphorus excretion ranged from 0 to 1.3×10-5μg P cell-1h-1.The main factors affecting the exretion and regeneration rate were the growth phase of ciliates and temperature,etc.Isotope dilution method was used to determine the nutrients regeneration rates of microzooplankton in situ.Most field test results supported the hypothesis that microzooplankton was the main nutrient regenerator.

microbial food web;microzooplankton;nutrient regeneration;excretion

张武昌(1973-),男,博士,研究员,主要从事海洋微型浮游生物研究。电子邮箱:wuchangzhang@163.com。

Q179

A

1001-6932(2016)03-0241-11

10.11840/j.issn.1001-6392.2016.03.001

2015-07-07;

2015-09-15

中国科学院战略性先导科技专项(XDA11030202.2);973项目(2014CB441504)。