西藏高原草地生态系统丛枝菌根真菌的地理分布

蔡晓布,彭岳林

西藏大学农牧学院,林芝 860000

西藏高原草地生态系统丛枝菌根真菌的地理分布

蔡晓布*,彭岳林

西藏大学农牧学院,林芝860000

摘要:西藏高原是地球上极具特色的地理单元,对生物物种的形成与演化具有重要影响。基于孢子形态学鉴定,对从藏东南到藏西北(海拔高差>3500 m,年均温、年均降水量差异分别>20 ℃、>800 mm)高原热带、亚热带、温带、亚寒带和寒带环境下发育而成的热性草丛、暖性草丛、温性草原、温性荒漠、高寒草甸草原、高寒草原、高寒荒漠和高寒荒漠草原中的AM真菌群落进行研究,结果表明,不同类型草地间AM真菌的群落相似度普遍较低,环境对AM真菌群落具有重要影响。从藏东南到藏西北,不同类型草地间AM真菌的群落相似度呈下降趋势(Jaccard相似性系数从0.52降至0.20),AM真菌群落组成及结构变化渐趋加大,不同草地中的同种植物(包括广谱种、青藏高原特有种)AM真菌群落相似度亦不同。沿藏东南到藏西北环境梯度,随草地寒旱程度的逐步加剧,AM真菌种的丰度,特别是种数、Shannon-Weiner指数在总体上趋于显著(P<0.05)下降,孢子密度则在总体上趋于显著提高,优势种比例、Shannon-Weiner指数亦表现出增加的趋势,表明AM真菌物种多样性虽趋于下降,但生存及对环境的适应能力趋于提高。海拔、土壤pH、有效磷和有机碳含量对AM真菌群落组成均具显著影响,但海拔对水热环境的影响决定着土壤环境的变化。因此,海拔和寒旱程度不断上升所导致的pH显著提高、土壤有机碳和有效磷含量显著下降的综合作用影响并决定着AM真菌的群落组成。研究结果对进一步理解西藏高原生物多样性的产生和维持机制等具有重要的参考价值。

关键词:AM真菌;物种多样性;生物地理分布;草地生态系统;西藏高原

研究生物体的时空分布规律、生存状态、丰富程度及其原因是深入了解生物多样性地理分布、产生和维持机制的重要基础[1]。因此,更为深入了解微生物的生物地理分布对保护与维持生态系统多样性、预测不同区域微生物的作用与影响至关重要[1]。长期以来,人们对大生物的生物地理分布开展了大量研究,对多样性很高的微生物的研究却非常缺乏[1- 2],认为微生物的生物多样性水平完全不同于大生物[3],不存在生物地理分布[4- 5],并认为这主要与微生物自身的生理与繁殖特性等因素有关[6]。同时,过去基于培养的研究错过了对大多数微生物多样性的发现亦是重要原因[7]。近年来,研究者对微生物,特别是AM真菌等不可培养的微生物的生物地理分布给予了更多的关注[1,8]。越来越多的证据表明,微生物不仅存在着生物地理分布特征[1,8- 11],且类似于大生物的地理分布[1],尽管对此仍存争论[4,12- 14]。新近,一些研究者基于对根际土壤中或植物根内AM真菌DNA的提取,研究了AM真菌分类群(OUT, operational taxonomic unit)的地理分布特征[10- 11,15]。与此同时,一些学者则通过对已发表文献的分析,就AM真菌的地理分布格局开展了研究[16- 17]。研究发现,自然状态下的微生物也有不同的数量、分布和多样性,不同地点的微生物群落及生物地理分布特征不同,且微生物的群落组成影响着生态系统的过程[1,18- 19]。因此,许多研究者认为环境异质性是影响微生物群落空间异质性的重要因素[20],微生物群落趋于生境选择[17, 21- 23]。但亦有研究认为寄主植物对AM真菌群落的影响较生境更为重要[14]。

西藏高原是地球上一个极具特色的地理单元,对生物物种的形成与演化具有重要影响。近10年来,西藏高原AM真菌相关研究主要集中在群落组成和物种多样性[24- 25],以及AM真菌群落沿海拔梯度的变化[25- 26]等方面。已有工作多以局部区域、个别生态系统为对象,且取样方法、研究手段等方面亦有所不同[24- 26],难以从大尺度上了解西藏高原AM真菌的地理分布特征。从生物地理学的层面看,环境影响并决定着植物的群落结构和物种多样性[27],高生产力环境发育和保存了古老的植物区系和最大的物种多样性,低生产力环境则为现代植物种系的演化、发生创造了条件,但植物群落物种多样性较低[28- 29]。从藏东南到藏西北,地理跨度(>2000 km)巨大、环境变化剧烈(海拔高差>3500 m,年均温和年均降水量差异分别>20℃、>800 mm),高原热带、亚热带、温带、亚寒带和寒带环境依次展布,气候呈暖温湿润—寒冷半湿润—寒冷半干旱—寒冷干旱的规律性变化,渐次呈现出从热性草丛到高寒荒漠、从黄壤到高山寒漠土的植物、土壤地理分布格局[30]。因此,在从藏东南到藏西北这一环境梯度上,植物区系由古老到年轻、植物物种多样性和资源生产力由高到低的变化将可能意味着AM真菌亦具有与环境、植物相适应的地理分布格局。因此,以横贯西藏高原多类草地的这一地理带为轴线,有助于进一步探究不同区域AM真菌的地理分布及其环境影响等重要科学命题。

1材料和方法

1.1样品采集

西藏高原不同类型草地AM真菌孢子繁殖的高峰期(孢子形态亦较稳定)均在暖季(5—9月),但受海拔主导的水、热环境影响,藏东南地区AM真菌的最适产孢时间相对较早(5—6月),其它区域7—9月孢子数量则较大。因此,本研究中均以各区域AM真菌的产孢高峰期作为采样期。其中,藏东南热性草丛、暖性草丛供试样品采集于2010年5—6月,藏中温性草原、温性荒漠供试样品采集于2008年8—9月,藏北高寒草原、高寒草甸草原供试样品分别采集于2009年8—9月、2013年8—9月,藏西北高寒荒漠草原、高寒荒漠供试样品采集于2011年8—9月。

由于西藏高原不同类型草地分布面积、植物种类差异悬殊,故在不同类型草地所采集的目标植物带根土壤混合样品数不同。具体采样时,为有效避免其它植物对目标植物根际的干扰,在各类草地中均选择具有丛生或片生特点的草本植物做为目标植物。目标植物选定后,即随机确定面积为1 m × 1 m的采样点3个(间隔100—150 m左右);于每个采样点铲除表层土壤2 cm,并按2—30 cm土层采集带根土样;之后,将每一目标植物的3个带根土壤样品组成1个混合样品(热性草丛、暖性草丛、温性草原、温性荒漠、高寒草甸草原、高寒草原、高寒荒漠草原和高寒荒漠混合样品数分别为13、14、17、18、13、30、19、11个)。在实验室将植物根系存放在4 ℃冰箱,土壤样品经室内自然风干后备用。土壤pH值、有机碳分别采用电位法、K2Cr2O7容量法-外加热法,中性和石灰性土壤、酸性土壤有效磷(P2O5)分别采用0.5 mol/L NaHCO3法、0.03 mol/L NH4F-0.025 mol/L HCl法测定。

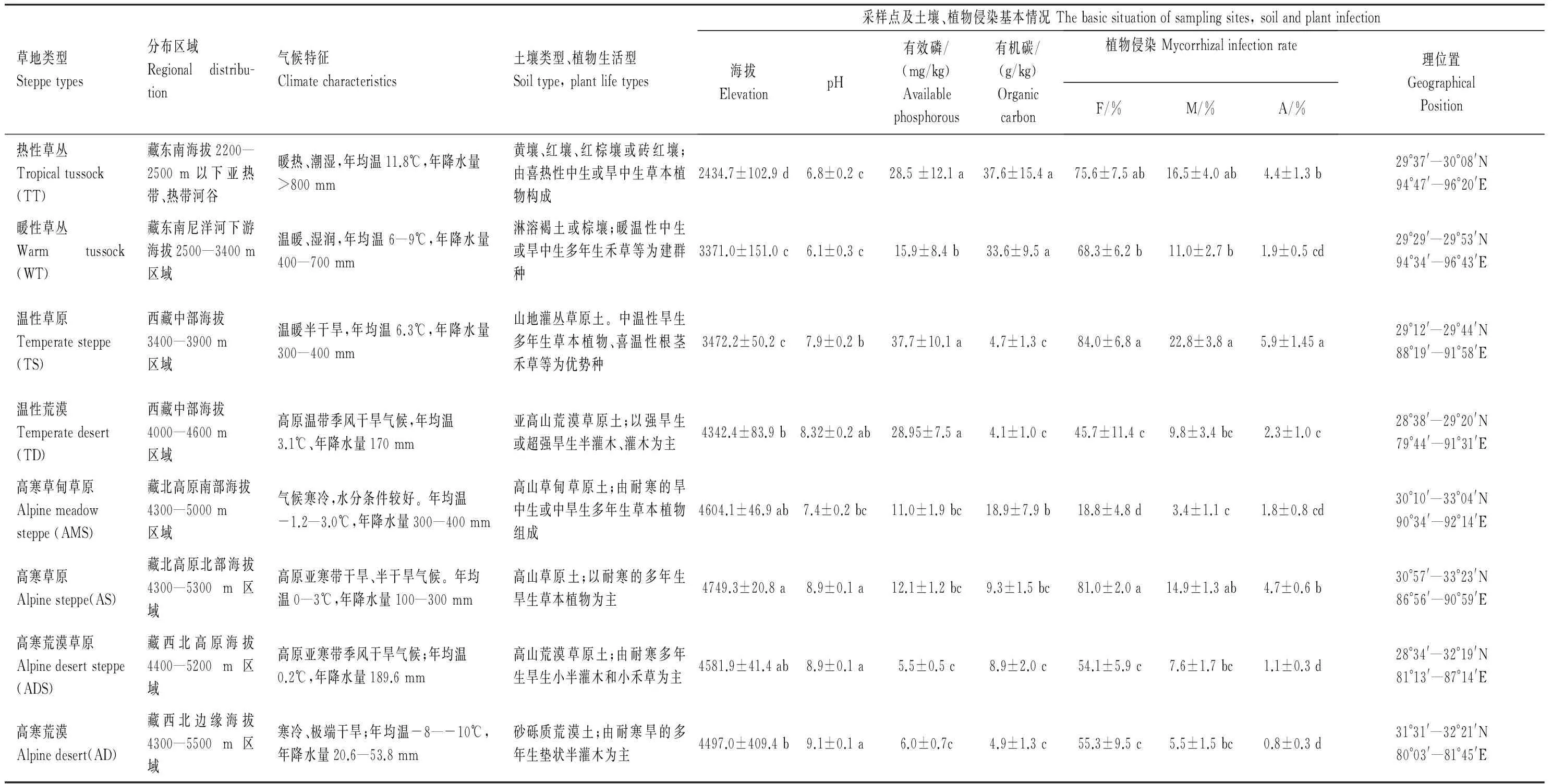

所涉各类草地采样点地理位置,以及土壤、植物侵染情况等见表1。

1.2AM真菌形态学鉴定

取100 g自然风干土样,采用湿筛倾析-蔗糖离心法筛取孢子;之后,用微吸管挑取孢子于载玻片上(加30%甘油浮载剂封片),显微观测并记录孢子颜色、连孢特征,测定孢子大小;压碎孢子后观测内含物、孢壁层次及各层颜色,测定各层孢壁的厚度(莱卡显微镜自带图像分析软件测定)等。鉴定中辅助使用Melzer′s试剂以观测孢子的特异性反应。综合以上观测结果,根据《VA菌根真菌鉴定手册》及INVNAM(http://invam.caf.wvu.edu/Myc-lnfo/)的分类描述进行属(种)检索、鉴定(表2)。

1.3数据计算方法

以3次重复平均值作为结果。

①孢子密度(SD)每100 g风干根层土样中不同AM真菌种的孢子数。

②种数(SN)指某生境中AM真菌的物种数。

③种的丰度(SR)每100 g根层土样所含AM真菌种的平均数:

SR= AM真菌种出现总次数/土壤样本数。

④物种多样性(H)采用Shannon-Weiner指数公式计算:

(1)

式中,k为某样点中AM真菌的种数,Pi为该样点AM真菌种i的孢子密度占该样点总孢子密度的百分比。

⑤ 分离频度(IF)某AM真菌属(种)在样本总体中的出现频率:

IF= AM真菌某属(种)的出现土样数/总土样数)× 100%

据此将AM真菌划分为3个优势度等级:IF≥50%为优势属(种)、≥10%—<50%为常见属(种)、<10%为偶见属(种)。

此外,共有种、特有种分别指见于各类草地或仅见于一类草地的AM真菌。

⑥相对多度(RA)

RA=SD/ ∑SD× 100%

式中,SD为某样点AM真菌某属(种)的孢子数,∑SD为某样点AM真菌总孢子数。

表 1 不同类型草地分布特征及土壤、植物样品概况

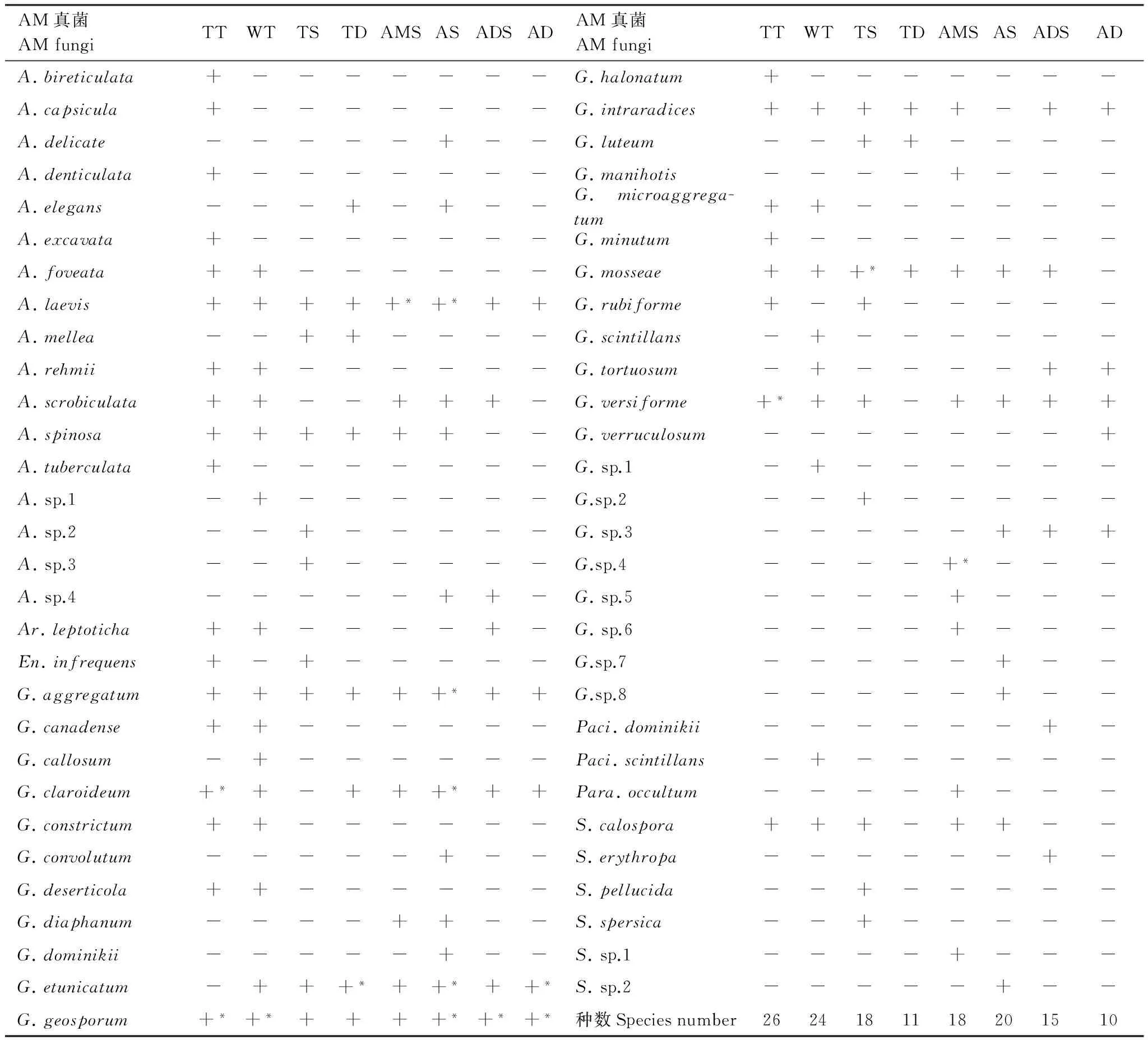

表 2 不同类型草地AM真菌

+ 表示某AM真菌在该草地出现Sign (+) indicates the AM fungi occurred in this sample site; *优势种 Dominant species of grassland types

⑦Jaccard系数

R=a/ (a+b+c)

式中,R为Jaccard系数,用以测度2个群落物种的亲缘关系;a指2个群落共同出现的物种数目;b、c指2个群落各自出现的物种数之和。据此,将群落物种组成的亲缘关系划分为极低(<0.20)、低(0.21—0.40)、中(0.41—0.60)、高(0.61—0.80)、极高(0.80—1.00)等5个等级。

差异显著性分析采用LSR法,相关分析、CCA分析分别采用Excel 2003、CANOCO 4.5计算。

2结果与分析

2.1不同类型草地AM真菌群落构成及其变化

西藏高原不同类型草地AM真菌属、种构成具有地域性分布特征。不同类型草地AM真菌属的构成介于2—5属之间,属数变化缺乏明显规律,环境条件差异很大的暖性草丛与高寒荒漠草原间、温性荒漠与高寒荒漠间AM真菌属的构成完全相同(表2)。

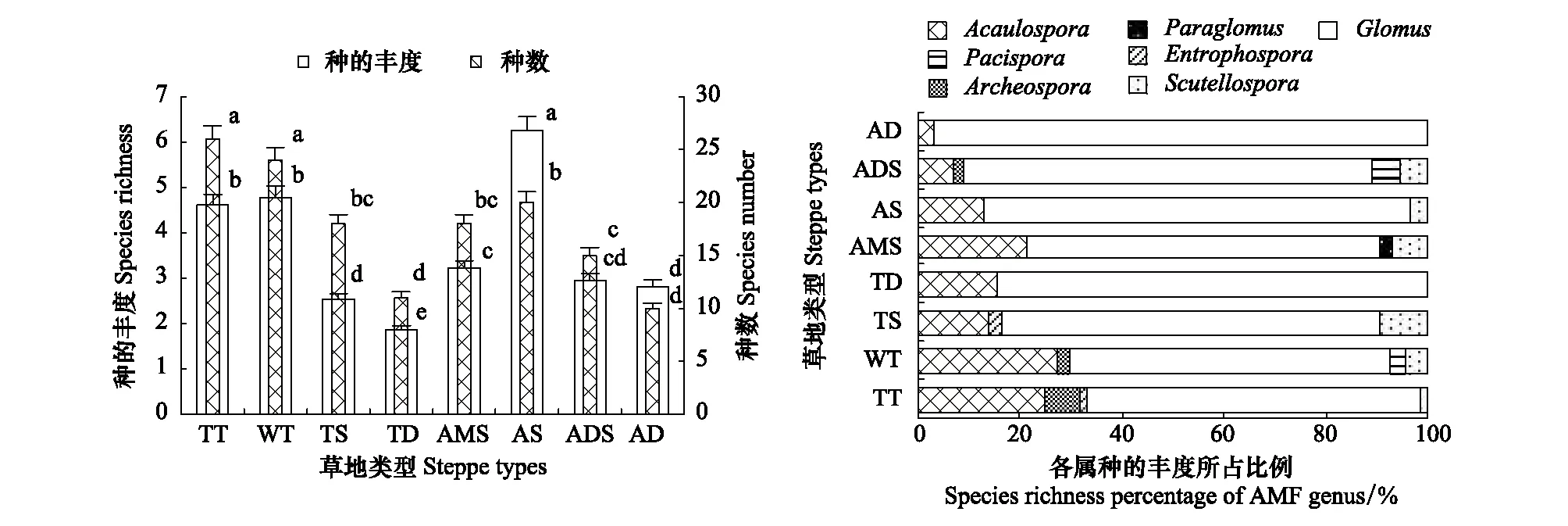

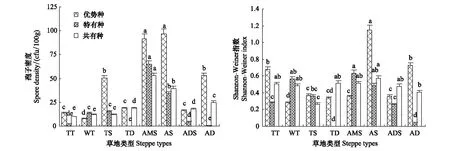

西藏高原草地生态系统中,AM真菌种数、种的丰度间呈显著正相关(r= 0.710*)。从藏东南到藏西北,草地AM真菌种数总体呈显著的波动式下降,种的丰度亦基本呈相同趋势,但高寒草原种的丰度显著高于热性草丛、暖性草丛(图1)。共有属(Acaulosporas、Glomus)对AM真菌种数、种的丰度均具重要影响,但各类草地中Glomus属种的丰度所占比重均远大于Acaulosporas属。同时,从藏东南到藏西北,Glomus、Acaulosporas属真菌种的丰度在不同类型草地中所占比重分别呈增、减趋势,其它各属对AM真菌群落构成的作用相对较小(图1)。

图1 各类草地AM真菌种数、种的丰度Fig.1 Number of AM fungi species and species abundance in all types of grasslandsTT:热性草丛Tropical tussock,WT:暖性草丛Warm tussock,TS:温性草原Temperate steppe,TD:温性荒漠Temperate desert,AMS:高寒草甸草原Alpine meadow steppe,AS:高寒草原Alpine stepp,ADS:高寒荒漠草原Alpine desert steppe,AD:高寒荒漠Alpine desert

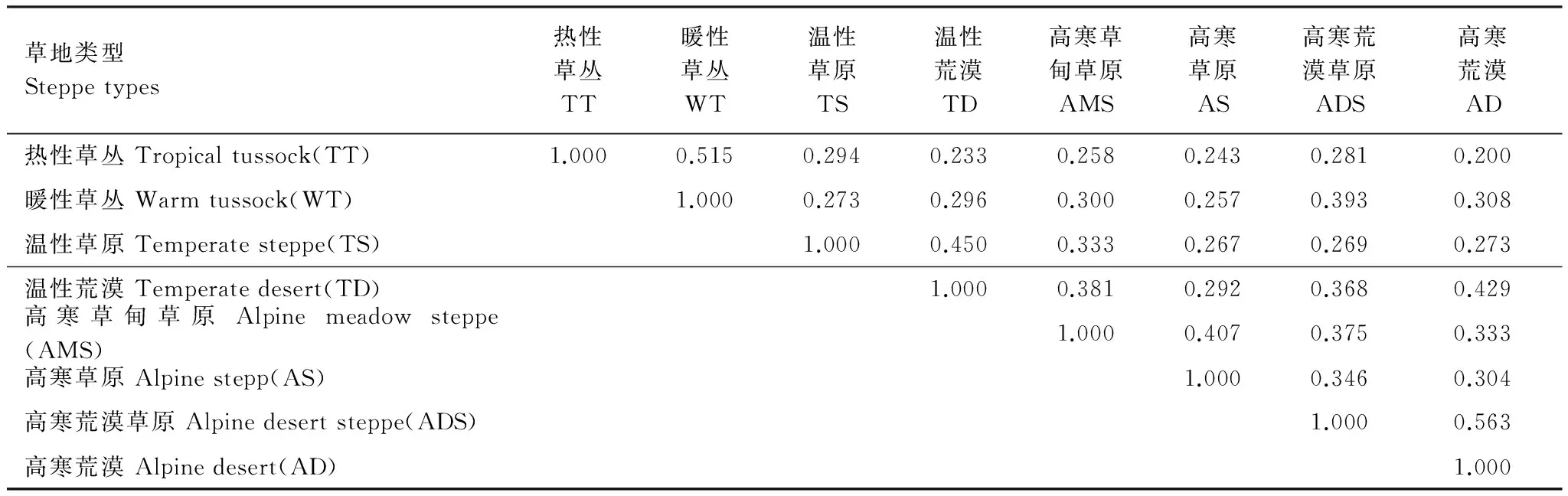

西藏高原不同类型草地间AM真菌的群落相似度普遍较低(表3),群落组成变化较大。从藏东南到藏西北,随环境差异的逐步扩大,热性草丛与其它草地间的Jaccard系数总体呈下降趋势,说明AM真菌对环境变化的敏感度差异不断增加,群落组成及结构变化渐趋加大。可见,草地环境对AM真菌的群落组成具有重要影响,且草地间环境差异越大,AM真菌Jaccard系数越低。

表3 西藏高原不同类型草地AM真菌Jaccard系数

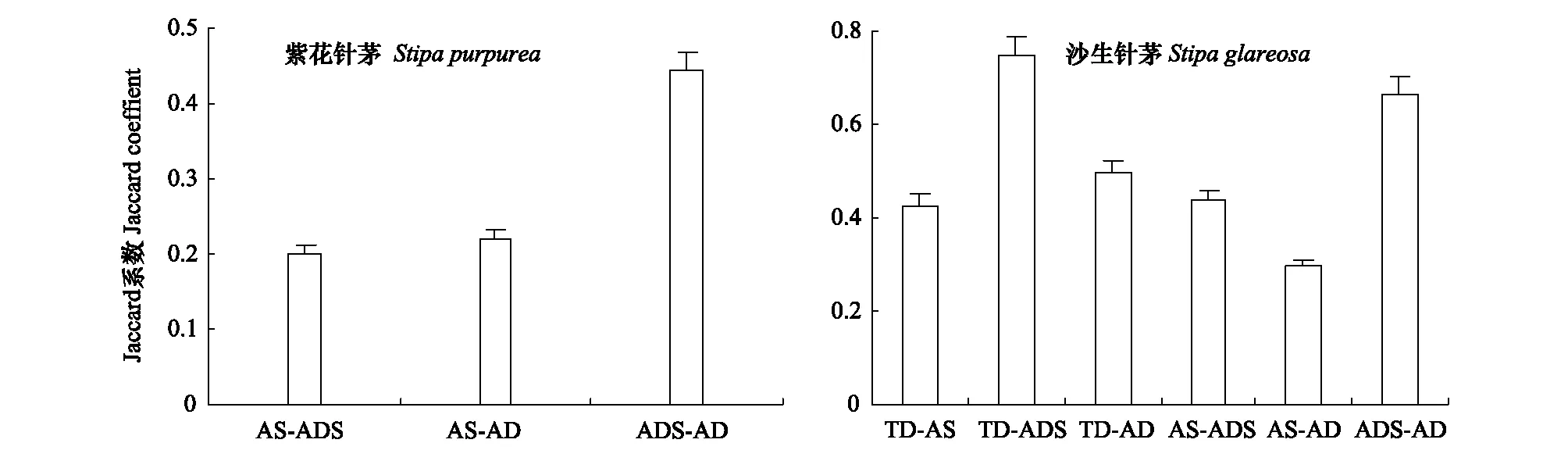

同种植物在不同草地中的AM真菌群落相似度亦不同,如不同草地中的青藏高原特有种紫花针茅(图2)、广谱种沙生针茅(图2)均表现出草地环境越接近且寒旱程度愈高,AM真菌群落相似度越大、亲缘关系相对越高的趋势,说明草地环境对AM真菌群落的影响较大。

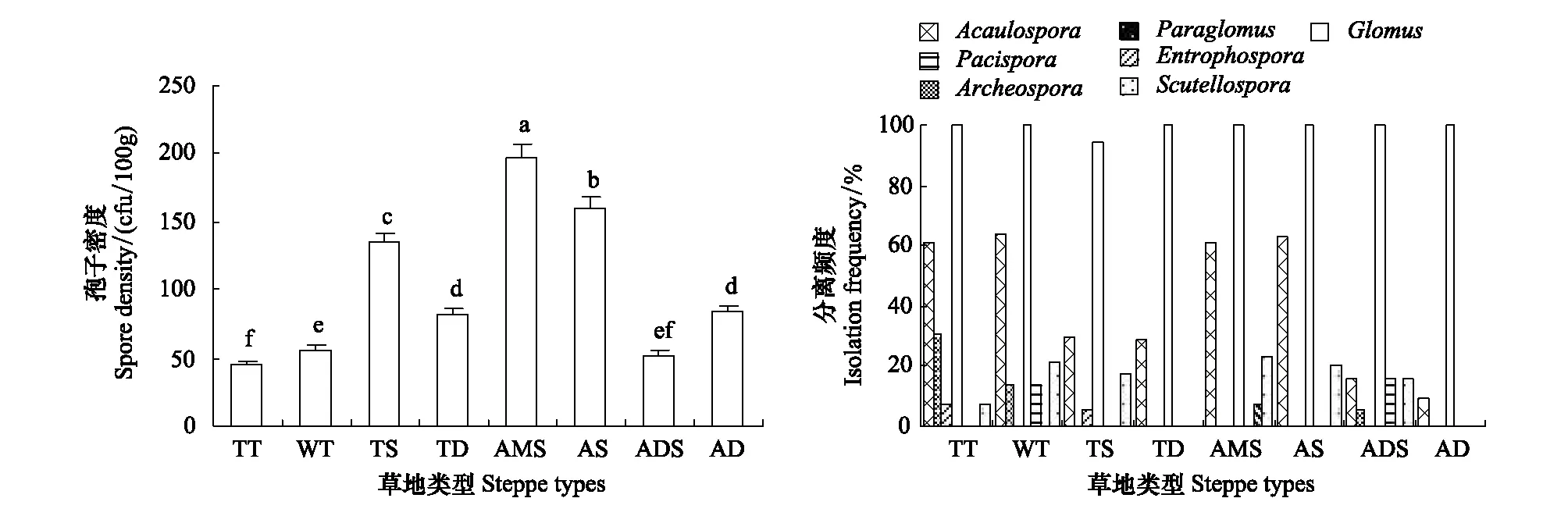

2.2不同类型草地AM真菌生存与繁殖能力及其变化

孢子密度是表征AM真菌群落生存状态的重要指标。西藏高原生态条件下,不同类型草地中AM真菌孢子密度显著不同,从藏东南到藏西北总体表现出不同程度的上升趋势,并以藏北高寒草甸草原、高寒草原孢子密度最大,而随海拔和寒旱程度的加剧,至藏西北高寒荒漠草原、高寒荒漠孢子密度的增加趋于显著下降(图3)。

从分离频度看,共有属中Glomus属均为优势属,Acaulospora属则仅为部分草地优势属;Scutellospora属见于6类草地,亦具较强的环境适应能力;其余各属则仅见于1—3类草地,环境适应能力弱或极弱(图3)。

图2 不同草地中青藏高原特有种紫花针茅、广谱种沙生针茅AM真菌群落相似性Fig.2 Community similarity of the AM fungi endemic species Stipa purpurea and the broad-spectrum Stipa glareosa in different grasslands of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau

图3 不同类型草地AM真菌孢子密度、相对多度和分离频度Fig.3 Spore density, relative abundance and isolation frequency of the AM fungi in different types of grasslands

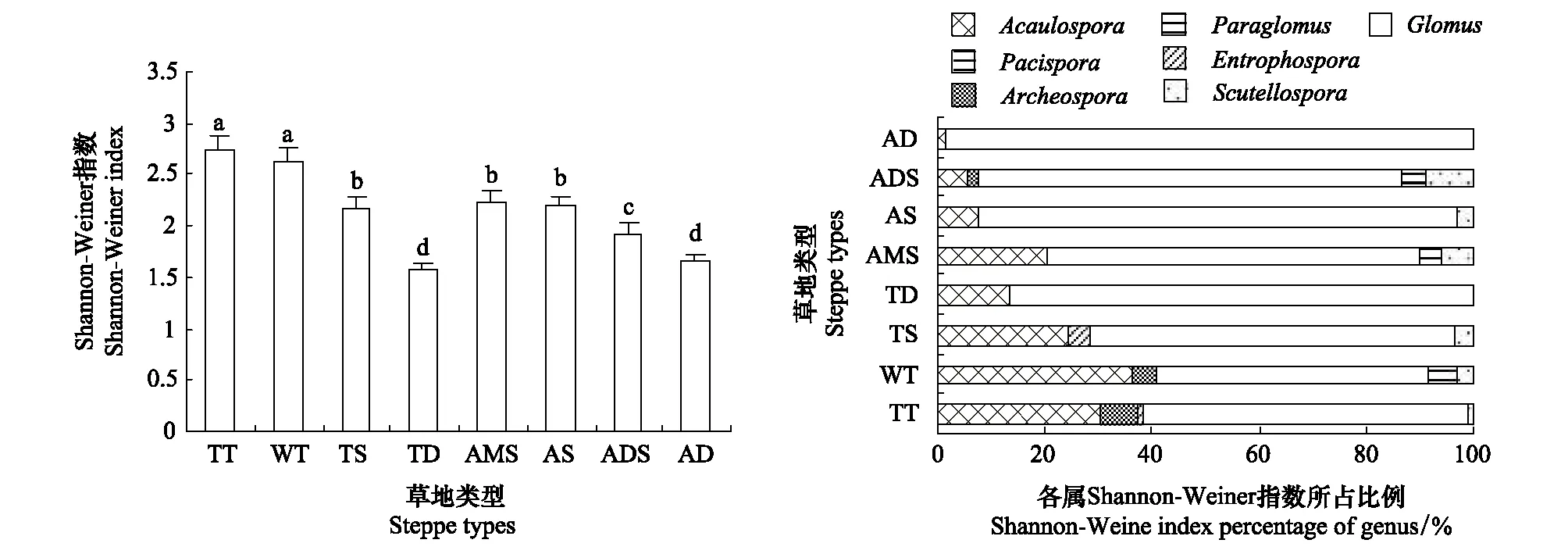

2.3不同类型草地AM真菌物种多样性及其变化

从藏东南到藏西北,AM真菌Shannon-Weiner指数在总体上虽趋显著下降,但下降过程表现出很大的波动性。从热性草丛到温性荒漠,Shannon-Weiner指数从最高降至最低,之后即呈不同程度的回升,但回升幅度随草地寒旱程度的加剧而下降(图4)。

共有属对AM真菌物种多样性均具重要贡献。统计分析表明,Acaulosporas、Glomus属种数与Shannon-Weiner指数均呈极显著正相关(r值分别为0.794**、0.890**),Acaulosporas、Glomus属相对多度则与Shannon-Weiner指数分别呈极显著正相关和负相关(r值分别为0.869**、-0.888**)。各类草地中,Glomus属真菌Shannon-Weiner指数所占比重不仅均远高于Acaulospora属,且所占比重亦基本随草地旱寒程度的增加而提高,Acaulospora属则相反。其它各属在所涉及的草地中亦表现出一定的规律(图4)。可见,同类草地各属AM真菌间、各类草地同属AM真菌间Shannon-Weiner指数均不同,Glomus属真菌在很大程度上影响并决定着AM真菌的物种多样性。

图4 不同类型草地AM真菌Shannon-Weiner指数及各属所占比例Fig.4 The Shannon-Weiner index and the proportion of AM fungi in different types of grasslands

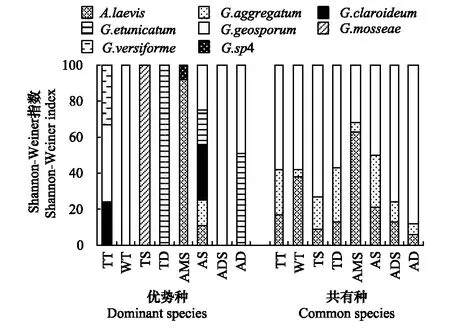

2.4AM真菌优势种、特有种与共有种及其变化

优势种、特有种和共有种体现着生物群落中的不同或相同个体对环境适应能力的差异。西藏高原草地生态系统中,AM真菌优势种、特有种、共有种分别占AM真菌总数的13.6%、54.2%和5.1%,并均以Glomus属真菌为主;不同类型草地中,AM真菌优势种、特有种和共有种所占比例分别在4.2%—25.0%、0—33.3%、11.5%—30.0%之间(表2)。地理分布上,从藏东南到藏西北,AM真菌群落中的优势种、共有种所占比例在总体上均趋于增加;特有种则有所不同(温性荒漠未见分布),由高寒草甸草原向水热环境的两极(特别是寒旱程度高的藏西北区域)均趋于下降。

孢子密度、Shannon-Weiner指数在总体上呈优势种>共有种>特有种的趋势;从藏东南到藏西北,不同类型草地优势种、共有种孢子密度、Shannon-Weiner指数在总体上均趋于不同程度的提高;特有种则在总体上表现出藏北>藏东南>藏中>藏西北的趋势(图5)。

图5 不同草地AM真菌优势种、特有种、共有种变化Fig.5 The changes of the dominant, endemic and common species in different types of grasslands同类草地不同小写字母表示差异显著性达5%水平

同类草地、不同草地中,优势种、共有种Shannon-Weiner指数均不同,如共有种Shannon-Weiner指数在总体上表现出G.geosporum>G.aggregatum>A.laevis的趋势。见,即使是共有种,其物种多样性及在群落中的作用亦受草地环境的强烈影响(图6)。

图6 不同草地AM真菌优势种、共有种H值所占比重 Fig.6 The proportions of H value of the AM fungi dominant species, common species in different types of grasslands

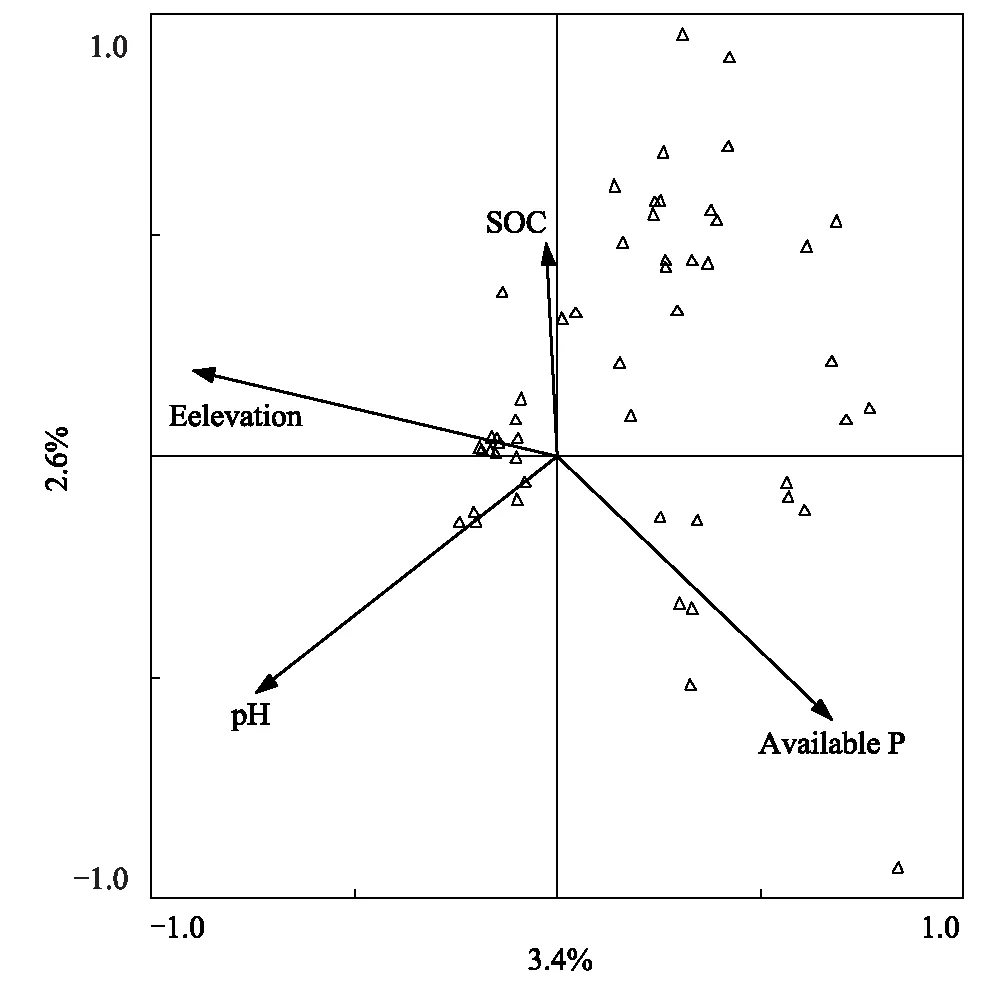

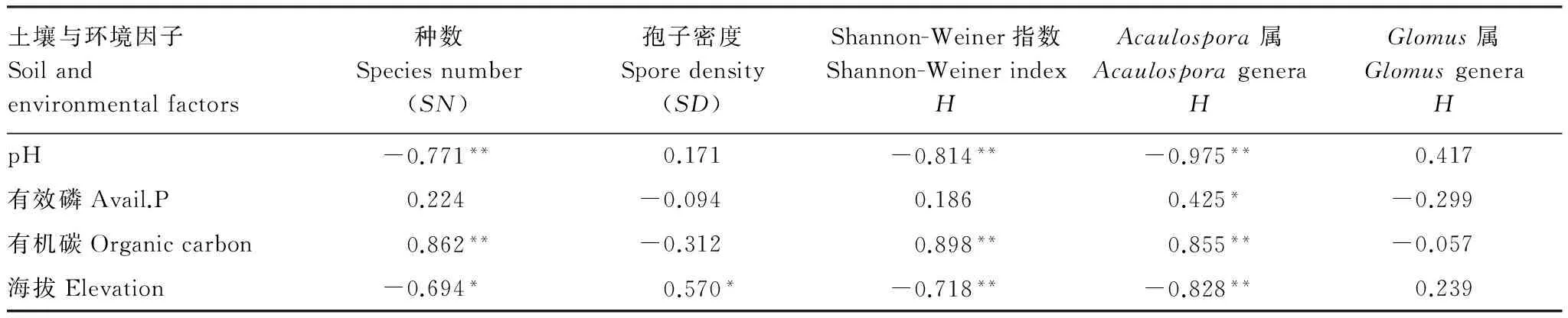

2.5环境与土壤因子对AM真菌地理分布的影响

CCA分析结果表明,第一轴和所有轴蒙特卡罗检验的P值均<0.01,第一轴和第二轴的解释量分别为3.4%和2.6%。海拔、土壤pH值、有效磷和有机碳对AM真菌的群落均具显著影响。其中,海拔是影响AM真菌群落的主要因素(图7)。

图7 不同类型草地土壤中AM真菌物种组成与环境因子的CCA排序Fig.7 The composition of the AM fungi species and the CCA sequencing in different types of grasslands

环境因子对AM真菌种数、孢子密度和Shannon-Weiner指数均具重要影响,环境因子对Acaulospora属的影响显著高于Glomus属(表4)。

3讨论

生物群落结构、种群组成、物种多样性及其差异是反映生物地理分布的重要指标[31]。从整体看,西藏高原环境并不利于AM真菌的种群发展,不同类型草地AM真菌种数均较少,藏东南热性草丛AM真菌种数亦仅为其它地区多类生态系统平均种数的52.6%[32]。但是,西藏高原不同草地生态系统AM真菌的群落组成、物种多样性显著不同。AM真菌的群落形成受菌丝扩散[33]和自然扩散[13]的严重限制,人为因素(尤其是农业)则是推动其孢子扩散的主要原因[13]。从藏东南到藏西北,不同草地间崇山阻隔,彼此处于相对隔离的状态,加之地广人稀(藏北、藏西北地区多属“无人区”),人类干扰极为有限或无干扰,多类草地尚处于原生状态,阻断了AM真菌的人为扩散过程。近年研究表明,资源的限制是菌根共生体产生局域适应性的主要驱动力[34],尽管地理距离、土壤温度和湿度、植物群落类型等对AM真菌分布、群落结构均具重要影响,但生境(地理距离、土壤温度和湿度)或扩散限制的影响对AM真菌的群落形成可能更具重要作用[17]。新近基于全球采样和高通量测序分析,研究者发现不同的地史成因亦影响并决定着AM真菌的地理分布[10]。因此,受生境和扩散限制的影响,西藏高原不同类型草地中AM真菌群落组成的显著差异应主要在于不同环境中AM真菌的自然进化。而在崇山阻隔,草地环境差异悬殊的条件下,部分草地间AM真菌属的构成相同、共有种所占比例很大(如暖性草丛、高寒荒漠草原间共有种分别占45.8%、73.3%、温性荒漠、高寒荒漠间共有种分别占54.5%、60.0%)的现象(表1),亦在一定程度上体现了西藏高原不同类型草地中AM真菌的平行进化过程。与此同时,宿主植物显著的地理分布特征,以及其对AM真菌所具有的一定程度的选择性[14],亦可能是影响西藏高原AM真菌地理分布格局的重要因素。

一般而言,在影响AM真菌群落结构的诸多土壤因子中,土壤pH、土壤有机质、土壤有效磷的影响最为显著[35]。一些研究甚至认为,由于土壤pH决定着植物群落的构成,因而对AM真菌群落、菌丝生长亦具有关键影响[36-37],通过土壤pH变化可以预测AM真菌群落的变化[38]。一些研究则发现,温度、降水量对AM真菌群落及菌丝发育具有重要影响[39- 40]。本研究中,相对于土壤环境变量,海拔对AM真菌群落的影响最为显著。

表4 环境因子对AM真菌种数、种的丰度和Shannon-Weiner的影响

有关研究表明,影响AM真菌群落的多种因素沿海拔梯度所产生的相应变化均可能影响AM真菌的功能和组成[25],其中温度的影响至关重要[41],海拔梯度主要通过影响温度、降水量而影响植物群落和AM真菌的群落分布[41]。最近几年,国内一些研究者对藏东南色季拉山等高大山体开展了研究,发现并证实海拔所导致的温度和降水量变化对AM真菌群落组成具有显著影响[25- 26]。尽管本研究所涉及的草地类型、地域多而广泛,但从藏东南到藏西北草地类型递变的实质是由于海拔高度的逐步提升所导致的温度、降水量的不断下降,这不仅决定着植物群落的组成,对土壤的形成与发育亦具深刻影响。因此,沿这一环境梯度,由于气候渐由潮湿向湿润、半干旱、干旱类型过渡,在植物多样性、资源生产力渐趋降低[30]的同时,土壤环境亦发生着相应的变化。如从藏东南到藏西北,随海拔和干旱程度的不断提高,土壤钙积过程、盐碱化过程均呈不同程度的提高,其结果是导致土壤pH值的不断提高。统计分析表明,本研究中海拔与土壤pH值的相关系数为0.735**,海拔与土壤有效磷、有机碳含量的相关系数分别为-0.631*、-0.719**,这是导致从藏东南到藏西北AM真菌种的丰度,特别是种数、Shannon-Weiner指数在总体上趋于显著下降、孢子密度趋于显著提高的主要原因。但从局部看,环境条件相对较好的西藏中部草地AM真菌种的丰度、多样性指数不同程度的低于藏北、藏西北草地,则与该区域草地退化严重、植被盖度低有关[42-43]。可见,海拔主导下的水热环境所导致的土壤环境变化的综合作用在整体上影响并决定着西藏高原草地生态系统中AM真菌的地理分布,从藏东南到藏西北AM真菌物种多样性虽趋显著下降,但长期的自然进化则使AM真菌主要通过强化繁殖与产孢的策略提高其生存与抗逆能力。盖京苹等对藏中、藏北草地的研究亦有AM真菌孢子密度、Shannon-Weiner指数随草地寒旱程度提高分别表现出增、减趋势[44]的类似结果。但土壤pH值与孢子密度、物种多样性分别呈正相关和极显著负相关的结果则与其它研究完全不同[45-46]。需要强调的是,尽管随不同类型草地海拔高度的变化,气温、降雨量、植物类型、土壤性质等均会发生相应变化,但对此问题的上述讨论仅仅是基于一般科学原理的推测,尚缺乏全面、具体的数据支撑,如果能进一步了解西藏高原环境,特别是水、热梯度变化对AM真菌群落的影响,将有助于深入理解AM真菌群落沿海拔梯度变化的实质和地理分布特征。

从藏东南到藏西北,各类草地优势种和共有种所占比例、优势种和共有种Shannon-Weiner指数在总体上均趋于不同程度的提高,这是AM真菌对逆境适应策略的另一重要体现。特有种是生物群落中对特定环境具有特殊适应能力的种。Zinger等研究发现,尽管高山土壤中真菌群落受生境的影响,但仅有少数几个种属于特有种[23]。本研究中,除温性荒漠未见分布,其它7类草地特有种比例高达10%—33.3%。但沿藏东南到藏西北环境梯度,特有种所占比例、Shannon-Weiner指数并未表现出随草本植物、青藏(西藏)高原特有植物种比例增加而提高的趋势。

对群落相似度的有关研究发现,洲际尺度上AM真菌的群落相似度无显著差异,而在全球大尺度背景下,随着地理距离的增加,AM真菌的群落相似度下降[17]。本研究则表明,西藏高原环境对AM真菌群落及物种多样性具有很大影响,群落相似度在区域尺度上即已表现出明显差异。从藏东南到藏西北,由于环境对AM真菌群落的影响逐步增大,群落演替过程不断加快,Jaccard相似性系数从0.52降至0.20。不同草地中的同种植物(包括广谱种、青藏高原特有种)AM真菌群落相似度亦明显不同,亦说明生境对AM真菌群落的影响较大。可见,随草地旱寒程度的提高,环境条件的逐步恶化抑或生存压力的不断强化是推动植物、AM真菌协同进化的关键因素。

西藏高原独特的地史成因和生物进化过程对研究AM真菌的地理分布问题提供了一个重要平台。但是,基于AM真菌形态学鉴定所得出的本项研究结果具有一定的局限性。因此,利用分子生物学方法系统地开展此类研究,对深入理解并揭示西藏高原AM真菌的地理分布,预测AM真菌群落变化对高原环境的影响与作用等均具重要意义。

参考文献(References):

[1]Jennifer B Hughes Martiny, Brendan J M Bohannan, James H Brown, Robert K Colwell, Jed A Fuhrman, Jessica L Green, M Claire Horner-Devine, Matthew Kane, Jennifer Adams Krumins, Cheryl R Kuske, Peter J Morin, Shahid Naeem, Lise Øvreås, Anna-Louise Reysenbach, Val H Smith, James T Staley. Microbial biogeography: putting microorganisms on the map. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2006, 4(2): 102- 112.

[2]Jessica Green, Brendan J M Bohannan. Spatial scaling of microbial biodiversity. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 2006, 21(9): 501- 507.

[3]Finlay B J, Esteban G F, Olmo J L, Tyler P A. Global distribution of free-living microbial species. Ecography, 1999, 22(2): 138- 144.

[4]John Whitfield. Biogeography: Is everything everywhere?. Science, 2005, 310(5750): 960- 961.

[5]Jani Heino, Luis Mauricio Bini, Satu Maaria Karjalainen, Heikki Mykrä, Janne Soininen, Ludgero Cardoso Galli Vieira, José Alexandre Felizola Diniz-Filho. Geographical patterns of micro-organismal community structure: are diatoms ubiquitously distributed across boreal streams?. Oikos, 2010, 119: 129- 137.

[6]Tom Fenchel, Bland J Finlay. The ubiquity of small species: patterns of local and global diversity. BioScience, 2004, 54(8): 777- 784.

[7]Melissa Merrill Floyd, Jane Tang, Matthew Kane, David Emerson. Captured diversity in a culture collection: case study of the geographic and habitat distributions of environmental isolates held at the American type culture collection. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2005, 71(6): 2813- 2823.

[8]Fierer N. Microbial biogeography: patterns in microbial diversity across space and time // Zengler K. Accessing Uncultivated Microorganisms: From the Environment to Organisms and Genomes and Back. Washington DC: ASM Press, 2008: 95- 115.

[9]John Davison, Maarja Öpik, Tim J Daniell, Mari Moora, Martin Zobel. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities in plant roots are not random assemblages. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2011, 78(1): 103- 115.

[10]Maarja Öpik, Martin Zobel, Juan J Cantero, John Davison, José M Facelli, Inga Hiiesalu, Teele Jairus, Jesse M Kalwij, Kadri Koorem, Miguel E Leal, Jaan Liira, Madis Metsis, Valentina Neshataeva, Jaanus Paal, Cherdchai Phosri, Sergei Põlme, Ülle Reier, Ülle Saks, Heidy Schimann, Odile Thiéry, Martti Vasar, Mari Moora. Global sampling of plant roots expands the described molecular diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Mycorrhiza, 2013, 23(5): 411- 430.

[11]Christopher J van der Gast, Paul Gosling, Bela Tiwari, Gary D Bending. Spatial scaling of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal diversity is affected by farming practice. Environmental Microbiology, 2011, 13(1): 241- 249.

[12]Bland J Finlay. Global dispersal of free-living microbial eukaryote species. Science, 2002, 296(5570): 1061- 1063.

[13]Søren Rosendahl. Communities, populations and individuals of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytologist, 2008, 178(2): 253- 266.

[14]Katie M Becklin, Kate L Hertweck, Ari Jumpponen. Host identity impacts rhizosphere fungal communities associated with three alpine plant species. Microbial Ecology, 2012, 63(3): 682- 693.

[15]Mari Moora, Silje Berger, John Davison, Maarja Öpik, Riccardo Bommarco, Helge Bruelheide, Ingolf Kühn, William E Kunin, Madis Metsis, Agnes Rortais, Alo Vanatoa, Elise Vanatoa, Jane C Stout, Merilin Truusa, Catrin Westphal, Martin Zobel, Gian-Reto Walther. Alien plants associate with widespread generalist arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal taxa: evidence from a continental-scale study using massively parallel 454 sequencing. Journal of Biogeography, 2011, 38(7): 1305- 1317.

[16]Öpik M, Vanatoa A, Vanatoa E, Moora M, Davison J, Kalwij J M, Reier U, Zobel M. The online database MaarjAMreveals global and ecosystemic distribution patterns in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (Glomeromycota). New Phytologist, 2010, 188(1): 223- 241.

[17]Stephanie N Kivlina, Christine V Hawkesb, Kathleen K Treseder. Global diversity and distribution of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2011, 43(11): 2294- 2303.

[18]Marcel G A van der Heijden, John N Klironomos, Margot Ursic, Peter Moutoglis, Ruth Streitwolf-Engel, Thomas Boller, Andres Wiemken, Ian R Sanders. Mycorrhizal fungal diversity determines plant biodiversity, ecosystem variability and productivity. Nature, 1998, 396(6706): 69- 72.

[19]Thomas Bell, Jonathan A Newman, Bernard W Silverman, Sarah L Turner, Andrew K Lilley. The contribution of species richness and composition to bacterial services. Nature, 2005, 436(7054): 1157- 1160.

[20]Fierer N, Jackson R B. The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2006, 103(3): 626- 631.

[21]Lucie Zinger, David P H Lejon, Florence Baptist, Abderrahim Bouasria, Serge Aubert, Roberto A Geremia, Philippe Choler. Contrasting diversity patterns of crenarchaeal, bacterial and fungal soil communities in an alpine landscape. PLoS One, 2011, 6(5): e19950, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019950.

[22]Bachar A, Al-Ashhab A, Soares M I M, Sklarz M Y, Roey Angel R, Ungar E D, Gillor O. Soil microbial abundance and diversity along a low precipitation gradient. Microbial Ecology, 2010, 60(2): 453- 461.

[23]Zinger L, Coissac E, Choler P, Geremia R A. Assessment of microbial communities by graph partitioning in a study of soil fungi in two alpine meadows. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2009, 75(18): 5863- 5870.

[24]蔡晓布, 彭岳林, 盖京苹. 西藏高山草原AM真菌生态分布. 应用生态学报, 2010, 21(10): 2635- 2644.

[25]Gai J P, Tiana H, Yang F Y, Christie P, Li X L, Klironomos J N. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal diversity along a Tibetan elevation gradient. Pedobiologia-International Journal of Soil Biology, 2012, 55(3): 145- 151.

[26]Li X L, Gai J P, Cai X B, Li X L, Christie P, Zhang F S, Zhang J L. Molecular diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi associated with two co-occurring perennial plant species on a Tibetan altitudinal gradient. Mycorrhiza, 2014, 24(2): 95- 107.

[27]Pacala S, Tilman D. The transition from sampling to complementary // Kinzig A P. eds. The Functional Consequences of Biodiversity: Empirical Progress and Theoretical Extensions. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002: 151- 166.

[28]Peter M Vitousek. Beyond global warming: Ecology and global change. Ecology, 1994, 75(7): 1861- 1876.

[29]Diana Lieberman, Milton Lieberman, Rodolfo Peralta, Gary S Hartshorn. Tropical forest structure and composition on a large-scale altitudinal gradient in Costa Rica. Journal of Ecology, 1996, 84(2): 137- 152.

[30]西藏自治区土地管理局. 西藏自治区土壤资源. 北京: 科学出版社, 1994: 51- 153.

[31]Arvie Odland, Roger del Moral. Thirteen years of wetland vegetation succession following a permanent drawdown, Myrkdalen Lake, Norway. Plant Ecology, 2002, 162(2): 185- 198.

[32]刘润进, 焦惠, 李岩, 李敏, 朱新产. 丛枝菌根真菌物种多样性研究进展. 应用生态学报, 2009, 20(9): 2301- 2307.

[33]Scott A Mangan, Gregory H Adler. Consumption of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi by terrestrial and arboreal small mammals in a Panamanian cloud forest.JournalofMammalogy, 2000, 81(2): 563- 570.

[34]Nancy Collins Johnson, Gail W T Wilson, Matthew A Bowker, Jacqueline A Wilson, R Michael Miller. Resource limitation is a driver of local adaptation in mycorrhizal symbioses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2010, 107(5): 2093- 2098.

[35]Matthias C Rillig. Arbuscular mycorrhizae and terrestrial ecosystem processes. Ecology Letters, 2004, 7(8): 740- 754.

[36]Ingrid M Van Aarle, Pål Axel Olsson, Bengt Söderström. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi respond to the substrate pH of their extraradical mycelium by altered growth and root colonization. New Phytologist, 2002, 155(1): 173- 182.

[37]Telgason Helgason, Alastair H Fitter. Natural selection and the evolutionary ecology of the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (Phylum Glomeromycota). Journal of Experimental Botany, 2009, 60(9): 2465- 2480.

[38]Michael S Fitzsimons, R Michael Miller, Julie D Jastrow. Scale-dependent niche axes of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Oecologia, 2008, 158(1): 117- 127.

[39]Mayra E Gavito, Peter Schweiger, Iver Jakobsen. P uptake by arbuscular mycorrhizal hyphae: effect of soil temperature and atmospheric CO2enrichment. Global Change Biology, 2003, 9(1): 106- 116.

[40]Christine V Hawkes, Iain P Hartley, Phil Ineson, Alastair H Fitter. Soil temperature affects carbon allocation within arbuscular mycorrhizal networks and carbon transport from plant to fungus. Global Change Biology, 2008, 14(5): 1181- 1190.

[41]Koske R E, Gemma J N. Mycorrhizae and succession in plantings of beachgrass in sand dunes. American Journal of Botany, 1997, 84(1): 118- 130.

[42]Liu Y J, He J X, Shi G X, An L Z, Maarja Öpik, Feng H Y. Diverse communities of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi inhabit sites with very high altitude in Tibet Plateau. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2011, 78(2): 355- 365.

[43]Su Y Y, Guo L D. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in nongrazed, restored and over-grazed grassland in the Inner Mongolia steppe. Mycorrhiza, 2007, 17(8): 689- 693.

[44]Gai J P, Christie P, Cai X B, Fan J Q, Zhang J L, Feng G, Li X L. Occurrence and distribution of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal species in three types of grassland community of the Tibetan Plateau. Ecological Research, 2009, 24(6): 1345- 1350.

[45]Andrew P Coughlan, Yolande Dalpé, Line Lapointe, Yves Piché. Soil pH-induced changes in root colonization, diversity, and reproduction of symbiotic arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi from healthy and declining maple forests. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 2000, 30(10): 1543- 1554.

[46]Jonas F Toljander, Juan C Santos-González, Anders Tehler, Roger D Finlay. Community analysis of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and bacteria in the maize mycorrhizosphere in a long-term fertilization trial. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2008, 65(2): 323- 338.

Geographical distribution of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in the grassland ecosystems of the Tibetan Plateau

CAI Xiaobu*, PENG Yuelin

AgriculturalandAnimalHusbandryCollegeofTibetUniversity,Linzhi860000,China

Abstract:The Tibetan plateau is a unique geographical unit that plays important roles in the formation and evolution of biological species. On the basis of spore morphology, we preliminarily investigated arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungal communities in tropical tussock (TT), warm tussock (WT), temperate desert steppe (TDS), temperate desert (TD), alpine meadow steppe (AMS), alpine steppe (AS), alpine desert (AD), and alpine desert steppe (ADS) environments in southeastern to northwestern Tibet (altitude > 3500 m; mean annual temperature difference > 20 ℃; mean annual amount of precipitation difference > 800 mm), including plateau tropic, subtropic, temperate, subfrigid, and frigid zones. The results showed that the community similarity of AM fungi in different types of grasslands was generally low, and the type of environment had an important effect on the AM fungal community. Community similarity of AM fungi in different types of grassland demonstrated a decreasing trend from southeastern to northwestern Tibet (Jaccard similarity coefficient decreased from 0.52 to 0.20). Changes in the composition and structure of the AM fungal community increased gradually. AM fungal community similarity for the same plant species (including a broad spectrum of species and species endemic to the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau) in different grasslands was also different. With a gradually aggravated degree of cold and drought in the grasslands along the environmental gradient from southeastern to northwestern Tibet, the abundance of AM fungi species, especially the number of species, showed significantly decreasing trends, according to the Shannon-Weiner index (P<0.05). At the same time, spore density demonstrated dramatically increasing trends, and the proportion of dominant species in relation to the Shannon-Weiner index also showed a tendency to increase. This indicated that although the diversity of AM fungi showed decreasing trends, their survival and adaptability to the environment tended to improve. The effects of altitude, soil pH, effective phosphorus, and organic carbon content on AM fungal communities were significant, whereas the effects of altitude on the hydrothermal environment determined the changes in the soil environment. Therefore, AM fungal community composition was determined by the comprehensive effects of a dramatic increase in pH and soil organic carbon and a dramatic decrease in effective phosphorus content due to the gradually increasing altitude and degree of cold and drought. Our results have an important reference value for the further understanding of the production and maintenance of organism diversity in the Tibetan Plateau.

Key Words:AM fungi, species diversity, geographical distribution of organisms, grassland ecosystem, Tibetan Plateau

基金项目:国家自然科学基金资助项目(41161043, 41461054)

收稿日期:2014- 11- 19; 网络出版日期:2015- 10- 10

*通讯作者

Corresponding author.E-mail: xbcai21@sina.com

DOI:10.5846/stxb201411192291

蔡晓布,彭岳林.西藏高原草地生态系统丛枝菌根真菌的地理分布.生态学报,2016,36(10):2807- 2818.

Cai X B, Peng Y L.Geographical distribution of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in the grassland ecosystems of the Tibetan Plateau.Acta Ecologica Sinica,2016,36(10):2807- 2818.