Critical care nurses' attitude towards life-sustaining treatments in South East Iran

Farideh Razban, Sedigheh Iranmanesh, Hasan Eslami Aliabadi, Mansooreh Azzizadeh ForouziNeuroscience Research Center, Institute of Neuropharmacology, University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, IranSchool of Nursing and Midwifery, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, IranBirjand University of Medical Sciences, Birjand, Iran

Critical care nurses' attitude towards life-sustaining treatments in South East Iran

Farideh Razban1, Sedigheh Iranmanesh2, Hasan Eslami Aliabadi3, Mansooreh Azzizadeh Forouzi11Neuroscience Research Center, Institute of Neuropharmacology, University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran2School of Nursing and Midwifery, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran

3Birjand University of Medical Sciences, Birjand, Iran

KEY WORDS:Life-sustaining treatments; Critical care nurse; Attitude; South East Iran

World J Emerg Med 2016;7(1):59–64

INTRODUCTION

The primary purpose of intensive care is focused on saving the life of individuals.Critical care professionals do not always succeed to restore the health, and death is common in intensive care units (ICUs).[1]Death is often viewed as a failure, and critical care specialists can cause a great damage by their efforts to treat illness, disease, and injury and save the life of patients.[2]This "life-saving" culture continues to drive life-sustaining treatments (LSTs) such as ventilator support, dialysis and cardiopulmonary resuscitation even the ultimate outcome will be death.[2]LSTs may prolong life but greatly reduce the quality of death.[3]Extending patient's life in a severely compromised state may be associated with unnecessary pain or sufferings for the patient and his/ her family.At this time, the patient's life may no longer worth living and the burden of the life far outweigh the benefit.[4]When implementation or continuance of such therapies is not benefitial to the patient, treatment is never prescibed (withholding) or the prescribed treatment should be stopped (withdrawing).[5]

Decisions about withholding or withdrawing LSTs are complex and pose moral, legal, and social problems.[6]Nurses are responsible for decision-making about LSTs for patients.[7]The nurse assists the patient to evaluate the positive and negative results of LSTs, thus making the decision that is most congruous with his/her values and beliefs.[8]The nurse cannot make an ultimate decision to initiate or give up a treatment,[9]and does not impose any decisions or values on the patient.[8]Asattitudes of individuals guide their behaviors,[10]attitude of nurses towards LSTs might affect their caring behaviors to patients.Moreover, the patient and his/her family may have come to appreciate the opinions and understanding of critical care nurses, and they may rely on nurses' advice about withholding or withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments.

Review of the literature indicated that there are a number of studies that examined health care providers' attitude towards LSTs.Sjokvist et al[11]in Sweden, Kim and Lee[12]in Korea and Cramel et al[13]in Israel assessed nurses' attitude towards LSTs.They reported that participating nurses believed that a patient has the right to refuse these treatments.[11–13]Some studies[11,14,15]assessed physician's attitude towards LSTs in Sweden, and stated that physicians have a general positive attitude towards limited use of life-sustaining treatment for a good death.

In Iran, there are no studies assessing health care providers attitude towards LSTs.Although some studies evaluated nurses,[16]nursing students[17]and medical students[18]attitude towards do not resuscitate (DNR) orders, they reported that in many key items participants showed negative attitude towards DNR orders.[16–18]They believed that DNR orders do not prevent unnecessary suffering and may cause legal problems for them.

Diverse cultural, religious, philosophical, legal and professional attitudes lead to great difference in attitudes and practice relating to LSTs.[19]In the review, no study was found on health care providers' attitude towards LSTs in countries whose main religion is Islam, such as Iran.Thus, this study was conducted to assess critical care nurses' attitude towards LSTs in the South East Iran.

According to Islam, human life is sacred and a gift from God.The Holy Quran ordains that "if anyone killed a person not in retaliation of murder, or (and) to spread mischief in the land it would be as if he killed all mankind, and if anyone saved a life, it would be as if he saved the life of all mankind".[20]It is an equal honour that all humankind enjoy, and all humankind are directed to preserve this valuable life regardless of individuals' level of function or contribution to society, let alone their health status.[21]For Muslims, everything possible must be done to prevent premature death.[1]When medical experts believe death is inevitable, withdrawal of withholding treatment is acceptable, because this is seen as allowing death to take its natural course.[22]According to Atashzadeh et al[23]in Iran, withholding and withdrawing LSTs are not legal.They go on that since there are no guidelines, legislations or offi cial statements concerning end-of-life care, Iranian physicians are not likely to write orders regarding withholding and withdrawing LSTs.They afraid of legal problems and criminal prosecution.[23]

METHODS

Design

In this study we used a cross-sectional descriptive design.Before the collection of any data, the study was approved by both Kerman University of Medical Sciences and the three hospitals (Shahid Bahonar, Afzalipour, and Shafa Hospitals) of the university.

Participants and procedures

Critical care nurses working in the hospitals were supervised by the hospitals of Kerman University of Medical Sciences between September and November 2013.The data were collected from 9 ICUs in the three hospitals.These ICUs comprised four traumatic ICUs in Shahid Bahonar Hospital, a general ICU and a surgical ICU in Afzalipour Hospital as well as a general ICU, an open heart ICU and a Neuro-ICU in Shafa Hospital.Convenience sampling was used for collection of data.Participation in the survey was voluntary and all responses were kept confidential.To ensure that the eligible staff were provided with an opportunity to participate in the study, the wards were repeatedly visited by a researcher, covering all three staff shifts (days, evenings, and nights).A total of 104 questionnaires were handed out by the third researcher, along with a letter containing information about the aims of the study.Eighty-four questionnaires were returned.The rate of response to the questionnaires was 80.76%.Within these questionnaires, 89% of all questions were answered.

Instruments

The questionnaire consisted of questions about age, gender, marital status, level of education, years of experience in ICU, etc.

To fulfill the aim of the study, a translated version of the "Ethnicity and Attitudes towards Advance Care Directives Questionnaire" was used.This questionnaire designed by Blackhall et al[24]in 1999.

It consists of two sections: (1) attitude towards use of life-sustaining/prolonging technology "general attitude", and (2) personal desire for use of life-support "personal desire".The "general attitude" was assessed through 13 items, each measured by a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).Six items were termed as "positively" (in favor of life-sustaining/prolonging technology) and seven items as "negatively" (opposed to life- sustaining/prolonging technology).Thus, the scores of negative items were reversed.The second part "personal desire" consists of 8 items in four different hypothetical situations.For the four items related to cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), three response choices were given (want, don't want, and not sure).For the four items related to mechanical ventilation, four response choices were given (want, don't want, not sure, and for a short time only).Higher scores imply greater personal desire for life-prolonging/sustaining technology.For translation of questionnaire from English into Farsi, the standard forward–backward procedure was applied.The items and the response categories were independently translated by two professional translators and then temporary versions were provided.Afterwards, they were back translated into English, and, after a careful cultural adaptation, the fi nal versions were provided.Translated questionnaires were subjected to pilot testing.Suggestions by nurses were combined into the fi nal version of the questionnaire.

Validity and reliability

Blackhall et al[24]reported acceptable internal (construct and content) and external validity (including extensive pilot testing) for this instrument.Also Ko et al[25]computed Cronbach's alpha for the scale with the sample of Korean and Mexican Americans and it was 0.89.In Iran, there was no study assessing the reliability and validity of this scale, so the validity and reliability of scale were checked again.The validity of scale was assessed through a content validity.Ten faculty members in Nursing and Midwifery School have reviewed the content of the scales from cultural aspects.They agreed on an acceptable validity (CVI: 0.83).To reassess the reliability of translated scale, alpha coefficients of internal consistency (n=20) was computed.The alpha coeffi cient for the instrument was 0.78.So the translated scale showed reasonable reliability and validity.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS version 20 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the data from a population with a normal distribution.Descriptive statistics was used for the study variables.The demographic factors were compared using Student's t test or one-way ANOVA.The results were of signifi cance with an α level of 0.05.

RESULTS

Participants

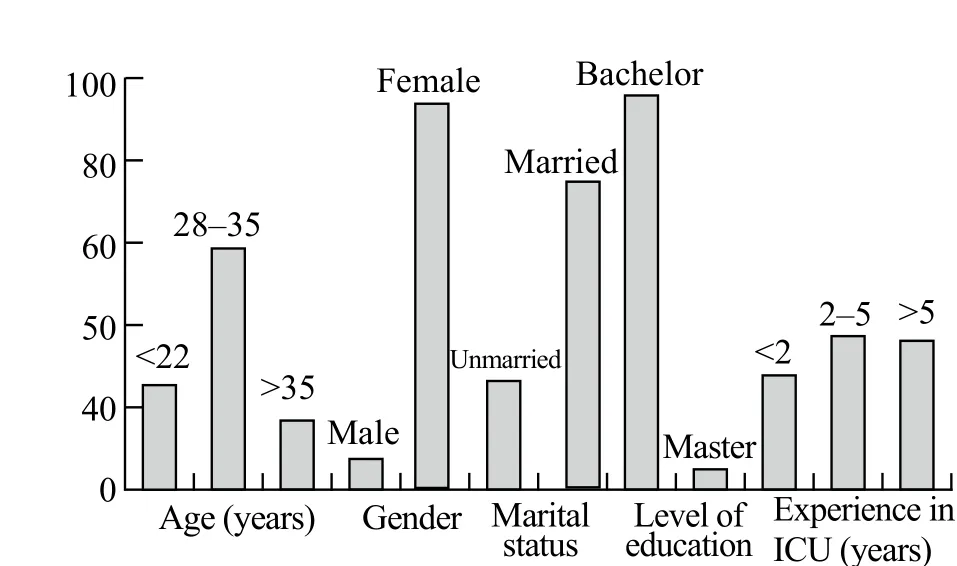

In this study, most (58.3%) of the participants were at age of 28–35 years (Figure 1), and 92.9% were female and 73.8% were married.Most of the participants had a degree of Bachelor of Science in nursing (95.2%).Approximately36.9 % of the participants had 2–5 years of experience in ICU and 35.7% had more than 5-year experience in ICU.

Figure 1.Background information of participants.

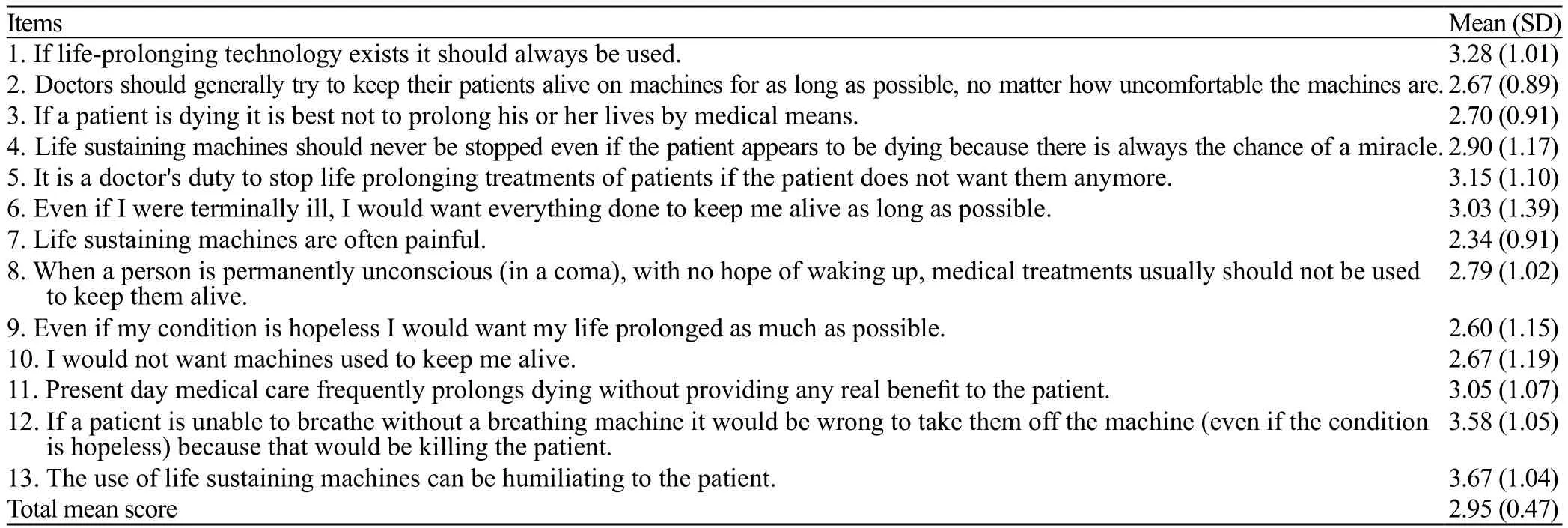

Table 1.The general attitude of critical care nurses towards LSTs

Descriptive fi ndings

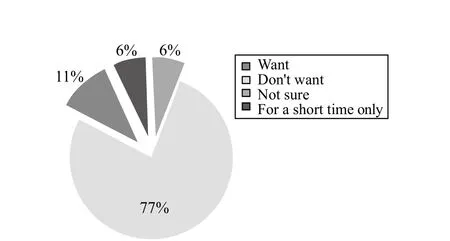

Descriptive analysis showed that the nurses were likely to accept LSTs, with a total mean score of 2.95 out of 5 (Table 1).The item "use of life-sustaining machines can be humiliating to the patient", and had the highest mean score of 3.67±1.04 among all items.The item "life-sustaining machines are often painful" and had the lowest mean score of 2.34±0.91 among all items.As demonstrated in Figure 2, most (77%) of the nurses showed that they have no intention to use LSTs including CPR and mechanical ventilation.Moreover, 6% of the nurses preferred CPR or mechanical ventilation and 6% favored mechanical ventilation for a short time only.The rest (11%) were not sure which method they preferred.

Correlations

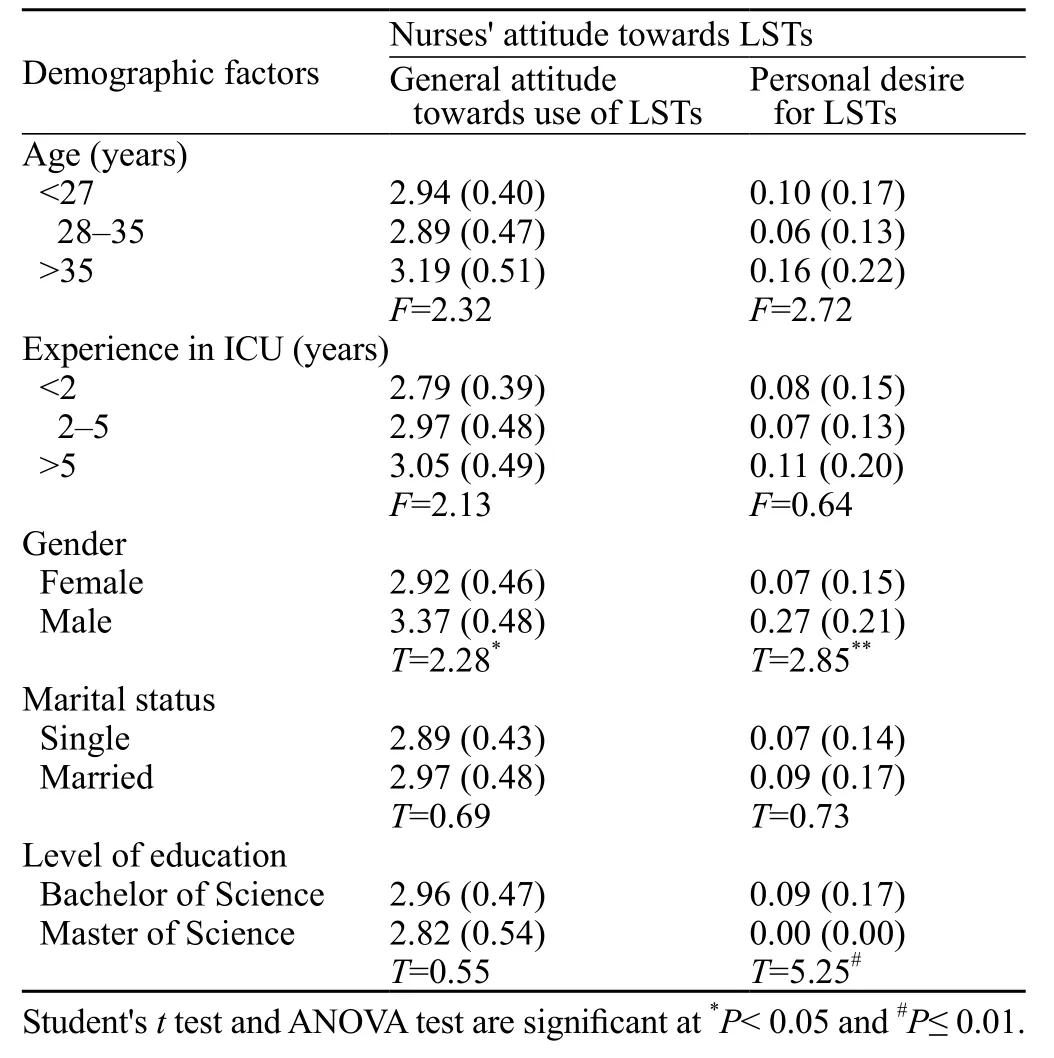

Analytic analysis revealed that the personal desire of male and female nurses as well as their general attitude towards LSTs was different (Table 2).Male nurses were more likely to use life-support in general (P=0.02) and had a more strong desire for such life-support for themselves than female nurses (P<0.01).The results of the analysis showed that the personal desire of critical care nurses for LSTs was infl uenced by their educational levels.Nurses with a Master Science degree had a less strong desire for LSTs than those with a degree of Bachelor of Science (P<0.001).

Figure 2.The preferation for life support in critical care nurses.

Table 2.Demographic factors affecting nurses' general attitude towards LSTs and their desire for LSTs

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to examine the attitude of critical care nurses towards LSTs in South East Iran.The results of the study indicated that a majority (77%) of nurses do not have a desire to use LSTs including CPR and mechanical ventilation.Sjökvist et al[26]reported that 59% of Swedish nurses stated that if they were the patients who are conscious and competent with pneumonia and sever cancer, they would wish to discontinue the ventilator treatment.Kim and Lee[12]also reported that 90.8% of Korean nurses would refuse LSTs if there was no chance of recovery.The low desire of nurses for life-support at the end of their life might be related to association of ICU nurses with pain and sufferings from LSTs of patients.Being witness to suffering patients causes nurses to be aware of their own vulnerability.[27]As shown in the present study, nurses mostly considered that "life-sustaining machines are often painful".They had the least positive preference towards this treatment (2.34±0.91).

Although most (77%) of nurses were reluctant to undergo LSTs, critical care nurses preferred the general use of LSTs (2.95 out of 5).It could be due to nurses' unawareness of the patients' wishes about use or forgoing of LSTs.At the end of life, patients may be unconscious or too cognitively impaired to communicate directly, and health care practitioners are unsure of the patients' wishes, advance directives are used.Advance directive is a legal document that requires medical care to include patients' preferences about medical treatment known before any serious injury or unplanned illness.[28]It provides guidance about a patient's wishes for treatment, provides legally valid instruction about treatment, and protects the patient's rights and the provider who honors the patient.[29]Tia et al[30]and Sjökvist et al[26]claimed that advance directive is one of the most important factorsinfluencing nurses' willingness to withdraw or continue life-support.Since 1991, advance directives have been developed in some Western countries.[31]In Islamic countries such as Iran, there is no advance directives regarding end of life medical decisions.[32]Based on Islamic law, "decisions about life belong to Allah, not to the person himself and documents to preserve or end personal life are not recognized" (Babgi, 2009).Of course, Islamic idea of humanity provides a provisional framework in which advance directive can generally be considered legitimate.[33]

In the present study, participants preferred likely the general use of LSTs.This finding is supported by studies on Iranian health care providers' attitudes towards DNR orders,[16–18]i.e.participants had negative attitudes towards many key items of DNR orders.In contrast, several studies[11–14,34]reported that health care providers considered that treatments are unnecessary when there is no hope of recovery.Participants' preference to general use of LSTs may be related to their religious beliefs.In the present study participants were Muslims.In Islam, life is sacred.According to Zahedi et al,[35]Muslims believe that death does not happen except by God's permission, as dictated in the Quran: "it is not given to any soul to die, but with the permission of Allah at an appointed time".[35]

Nurses' nearly neutral attitudes towards the general use of LSTs could also be due to their insuffi cient professional autonomy.Job autonomy has been an important factor for proactive idea implementation and problem solving.[36]Job autonomy fosters personal initiatives, expressing voice and suggesting improvement.[37]Iranmanesh et al[38]assessed critical care and oncology nurses' professional autonomy in South East Iran and reported that the participants had a moderate level of professional autonomy (3.08 of 5).Likewise, Amini et al[39]examined nurses' level of autonomy in North West Iran.The results of this study revealed that nurses had medium professional autonomy and most of the nurses compared with those in western societies have lower professional autonomy (Amini, Negarandeh, Ramezani-Badr, Moosaeifard, & Fallah, 2013).[39]

Another reason for nurses' moderate willingness to select the general use of LSTs might be the lack of end of life care education and specifi c training among Iranian nurses.Iranian nursing curriculum in all levels contains neither theoretical nor practical education about end of life care.The nurses' curriculum contains only 2–4 hours of theoretical education about death and caring for a dead body.Recently, just 0.1 credit units about palliative care are added to Master of Science in critical care nursing curriculum.Moreover, in the present study, participants with a Master of Science degree had less personal desire for LSTs compared to nurses with a Bachelor of Science degree (P<0.001).

The fi ndings of the present study indicated that male nurses had a more positive general attitude towards life-support (P=0.02) and were more likely to receive such life-support for themselves compared to female nurses (P<0.01).This is consistent with the finding of a previous study on attitudes towards LSTs among Hispanic Americans and older adults of Korean culture background.[25]The current study as well as the study of Ko et al[25]were conducted in context with male-dominant cultures.This specifi c cultural framework might affect the more positive attitude towards life-sustaining treatments among male participants in the current study.In Iranian culture, men usually earn more and view themselves as responsible for their families and they are in the position of making household decisions.[40]Hence, in this context, male family members might consider their presence vital for family survival.

Nurses have a professional responsibility to maintain a positive attitude towards clients at all times, so every effort must be made to put personal concern and feelings aside while communicating with clients, relatives and other health care professionals.[41]Decision-making about LSTs is a process that takes place in a team.Physicians are required to consult and discuss with other health care professionals such as nurses while making a final decision.[42]According to Curtis,[42]a large amount of data show that health care professionals depend on personal values and biases rather than ethics principles and outcomes while making decisions about LSTs.

In conclusion, some critical care nurses in Iran hold that LSTs should be used, regardless of their usefulness to dying patients.Lack of education, cultural and professional limitations, and religious issues may contribute to this kind of idea among Iranian nurses.These findings suggest that nurses' attitude towards LSTs can be changed through education on professional, religious and cultural aspects of palliative care and LSTs.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: Prior to the collection of any data, project approval was obtained from both Kerman University of Medical Science and the heads of the three hospitals the university supervises.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that there are no confl icts of interest related to the publication of this paper.

Contributors: Razban F proposed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the fi rst draft.All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts.

REFERENCES

1 Rocker G, Puntillo K, Azoulay É.End of life care in the ICU: From advanced disease to bereavement.Oxford University Press, 2010.

2 Sole ML, Klein DG, Moseley MJ.Introduction to critical care nursing 6: introduction to critical care nursing.Elsevier Health Sciences, 2012.

3 Negri S.Self-determination, dignity and end-of-life care: regulating advance directives in international and comparative perspective (Vol.7).Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2012.

4 Sheehan C, Potter M.Palliative care nursing.Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2011: 107–108.

5 Peirce AG, Smith JA.Ethical and legal issues for doctoral nursing students: a textbook for students and reference for nurse leaders.DEStech Publications, Inc., 2013.

6 Criner GJ, Barnette RE, D'Alonzo GE.Critical care study guide: text and review: Springer, 2010.

7 Matzo M, Sherman DW.Palliative care nursing: quality care to the end of life.Springer Publishing Company, 2009.

8 Wicclair MR.Conscientious objection in health care: Cambridge.Cambridge University Press, 2011.

9 Williams L.Lippincott's fast facts for NCLEX-PN.Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012.

10 Petty RE, Krosnick JA.Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences.Psychology Press, 2014.

11 Sjokvist P, Berggren L, Cook D.Attitudes of Swedish physicians and nurses towards the use of life-sustaining treatment.Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1999; 43: 167–172.

12 Kim S, Lee Y.Korean nurses' attitudes to good and bad death, lifesustaining treatment and advance directives.Nurs Ethics 2003; 10: 624–637.

13 Carmel S, Werner P, Ziedenberg H.Physicians' and nurses' preferences in using life-sustaining treatments.Nurs Ethics 2007; 14: 665–674.

14 Lindblad A, Juth N, Fürst CJ, Lynöe N.When enough is enough; terminating life-sustaining treatment at the patient's request: a survey of attitudes among Swedish physicians and the general public.J Med Ethics 2010; 36: 284–289.

15 Rydvall A, Lynöe N.Withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining treatment: a comparative study of the ethical reasoning of physicians and the general public.Crit Care 2008; 12: R13.doi: 10.1186/cc6786.Epub 2008 Feb 15.

16 Mogadasian S, Abdollahzadeh F, Rahmani A, Ferguson C, Pakanzad F, Pakpour V, et al.The attitude of Iranian nurses about do not resuscitate orders.Indian J Palliat Care 2014; 20: 21–25.doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.125550.

17 Abdollahzadeh F, Rahmani A, Paknejad F, Heidarzadeh H.Do not resuscitate order: attitude of nursing students of Tabriz and Kurdistan Universities of Medical Sciences.Iranian Journal of Medical Ethics and History of Medicine 2013; 6: 45–56.

18 Ghajarzadeh M, Habibi R, Amini N, Norouzi-Javidan A, Emami-Razavi SH.Perspectives of Iranian medical students about do-notresuscitate orders.Maedica (Buchar) 2013; 8: 261–264.

19 Elliott D, Aitken L, Chaboyer W.ACCCN's critical care nursing.Elsevier Australia, 2011.

20 Abdul-Rahman MS.The Meaning and Explanation of the Glorious Qur'an (Vol.10).MSA Publication Limited, 2008.

21 Fathalla WM.From quality of life to value of life; an Islamic ethical perspective.Ibnosina Journal of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences 2010; 2: 258–263.

22 Bloomer MJ, Al-Mutair A.Ensuring cultural sensitivity for Muslim patients in the Australian ICU: Considerations for care.Aust Crit Care 2013; 26: 193–196.

23 Atashzadeh Shorideh F, Ashktorab T, Yaghmaei F.Iranian intensive care unit nurses' moral distress: a content analysis.Nurs Ethics 2012; 19: 464–478.

24 Blackhall LJ, Frank G, Murphy ST, Michel V, Palmer JM, Azen SP.Ethnicity and attitudes towards life sustaining technology.Soc Sci Med 1999; 48: 1779–1789.

25 Ko E, Cho S, Bonilla M.Attitudes toward life-sustaining treatment: the role of race/ethnicity.Geriatr Nurs 2012; 33: 341–349.doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2012.01.009.Epub 2012 Mar 8.

26 Sjökvist P, Berggren L, Svantesson M, Nilstun T.Should the ventilator be withdrawn? Attitudes of the general public, nurses and physicians.Eur J Anaesthesiol 1999; 16: 526–533.

27 Eifried S.Bearing witness to suffering: the lived experience of nursing students.J Nurs Educ 2003; 42: 59–67.

28 Williams L.Lippincott's Nursing Procedures: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009.

29 Pozgar GD, MBA C.Legal and ethical issues for health professionals: Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2012.

30 Tai CCC, Ng DLL.Factors influencing decisions to withdraw or continue life support and attitudes towards treatment of the critically ill: a survey of registered nurses in intensive care units.Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare, 2011.

31 Swota AH.Culture, Ethics, and advance care planning.Rowman & Littlefi eld, 2009.

32 Al-Jahdali H, Baharoon S, Al Sayyari A, Al-Ahmad G.Advance medical directives: a proposed new approach and terminology from an Islamic perspective.Med Health Care Philos 2013; 16: 163–169.

33 Haker H, Bentele K.Medical ethics in health care chaplaincy (Vol.1).LIT Verlag Münster, 2010.

34 Esteban A, Gordo F, Solsona JF, Alía I, Caballero J, Bouza C, et al.Withdrawing and withholding life support in the intensive care unit: a Spanish prospective multi-centre observational study.Intensive Care Med 2001; 27: 1744–1749.Epub 2001 Oct 12.

35 Zahedi F, Larijani B, Tavakoly Bazzaz J.End of life ethical Issues and Islamic views.Iran J Allergy Asthma Immun 2007; 6 (Supple): 5.

36 Chirkov V, Ryan R, Sheldon KM.Human autonomy in crosscultural context: Springer, 2011.

37 DuBrin AJ.Proactive personality and behavior for individual and organizational productivity: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2013.

38 Iranmanesh S, Razban F, Nejad AT, Ghazanfari Z.Nurses' professional autonomy and attitudes toward caring for dying patients in South-East Iran.Int J Palliat Nurs 2014; 20: 294–300.doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2014.20.6.294.

39 Amini K, Negarandeh R, Ramezani-Badr F, Moosaeifard M, Fallah R.Nurses' autonomy level in teaching hospitals and its relationship with the underlying factors.Int J Nurs Pract 2015; 21: 52–59.

40 Bahramitash R.Gender and entrepreneurship in Iran.Microenterprise and the Informal Sector: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

41 Koutoukidis G.Tabbner's Nursing Care: Theory and Practice: Elsevier Australia, 2012.

42 Curtis JR.Managing death in the ICU: the transition from cure to comfort: the transition from cure to comfort.Oxford University Press, 2000.

Received August 6, 2015

Accepted after revision January 3, 2016

BACKGROUND: Life-sustaining treatments (LSTs) may prolong life but greatly decrease the quality of death.One factor influencing decision-making about withholding and withdrawing these treatments is the attitude of nurses.This study aimed to evaluate the attitude of critical care nurses towards life-sustaining treatments in South East Iran.

METHODS: In this cross-sectional study, "Ethnicity and Attitudes towards Advance Care Directives Questionnaire" was used to investigate the attitude of 104 critical care nurses towards lifesustaining treatments in three hospitals affi liated to Kerman University of Medical Sciences.

RESULTS: The fi ndings of this study indicated that although a majority of critical care nurses (77%) did not have personal desire for use of LSTs including CPR and mechanical ventilation, they had moderately negative to neutral attitude towards general use of LSTs (2.95 of 5).

CONCLUSIONS: These fi ndings suggest that nurses' attitude towards LSTs can be changed by inclusion of specific courses about death, palliative care and life-sustaining treatments in undergraduate and postgraduate nursing curricula.Educating Muslim nurses about religious aspects of LSTs may also improve their attitudes.

Corresponding Author:Mansooreh Azzizadeh Forouzi, Email: m_azzizadeh@kmu.ac.ir

DOI:10.5847/wjem.j.1920–8642.2016.01.011

World journal of emergency medicine2016年1期

World journal of emergency medicine2016年1期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Airway foreign bodies: A critical review for a common pediatric emergency

- End-tidal capnometry during emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia: a randomized, controlled study

- Intranasal ketamine for the treatment of patients with acute pain in the emergency department

- Analgesic effect of paracetamol combined with lowdose morphine versus morphine alone on patients with biliary colic: a double blind, randomized controlled trial

- Comparison of intravenous pantoprazole and ranitidine in patients with dyspepsia presented to the emergency department: a randomized, double blind, controlled trial

- A correlation analysis of Broselow™ Pediatric Emergency Tape-determined pediatric weight with actual pediatric weight in India