Assessment of a predictive score for pulmonary complications in cancer patients after esophagectomy

Xue-zhong Xing, Yong Gao, Hai-jun Wang, Shi-ning Qu, Chu-lin Huang, Hao Zhang, Hao Wang, Quan-hui YangDepartment of Intensive Care Unit, Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100021, China

Assessment of a predictive score for pulmonary complications in cancer patients after esophagectomy

Xue-zhong Xing, Yong Gao, Hai-jun Wang, Shi-ning Qu, Chu-lin Huang, Hao Zhang, Hao Wang, Quan-hui Yang

Department of Intensive Care Unit, Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100021, China

KEY WORDS:Respiratory insuffi ciencty; Esophagectomy; Predictive

World J Emerg Med 2016;7(1):44–49

INTRODUCTION

Esophagectomy is a very important method for the treatment of resectable esophageal cancer, which carries a high rate of morbidity and mortality.[1–2]Postoperative pulmonary complications (PCs) are reported to occur in 15.9% to almost 40% of patients who have undergone esophagectomy,[3–8]and are associated with increased inhospital death rate and decreased 3- and 5-year survival rates.[7]

Several risk factors are reported to be associated with increased postoperative PCs, such as increased age, operation duration, decreased forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1%), decreased diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO%), poor performance status (PS), salvage esophagectomy after definitive chemoradiotherapy, and the amount of blood loss.[3,5,8]In 2011, Ferguson et al[3]developed a predictive pulmonary risk score using the data of 516 patients after esophagectomy.The scoring system including four preoperative variables as age, performance status, FEV1% and DLCO% predicted the occurrence of postoperative major PCs with an area under the curve of 70.8%.In a subsequent external validation study with 136 patients, Reinersman et al[9]found good accuracyof the risk score system for predicting major pulmonary complications with a sensitivity of 76%.However, the scoring system was developed and validated from the patients of similar characteristics, and it has not been validated outside the United States of America.Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the pulmonary risk score in a high volume hospital in China.

METHODS

Patients

Patients who admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) after esophagectomy at Cancer Hospital of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) and Peking Union Medical College (PUMC) between September 2008 and October 2010 were enrolled in the study.Exclusion criteria included patients who underwent exploratory thoracotomy and induction therapy, and those who had incomplete data.This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cancer Hospital of CAMS and PUMC and performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.And patients' consents were waived because of the observational nature of this study.

To determine the sample size of the study, we defi ned the confi dence level as 95%, and the confi dence interval as 34% to 42% (major PCs rate was 38% in Ferguson et al study).Therefore, the sample size was 150, which was needed to validate the predictive score.

Preoperative staging and physiologic assessments

Preoperative staging was carried out according to the guidelines of the Department of Thoracic Surgery of Cancer Hospital of CAMS and PUMC, which included whole blood test, biochemical test, chest CT, abdomen ultrasound, barium contrast study, endoscopy, pulmonary function test, and electrocardiograpy.[10]Preoperative physiologic assessments were based on age older than 70 or less, results of pulmonary function tests including forced expiratory volume at 1 second (FEV1) ≥1.20 L, FEV1% ≥40.0%, and DLCO% ≥40.0%.Patients were advised to stop smoking one week before surgery.And they received antibiotic therapy for at least 3–5 days if pulmonary infection existed, and the therapy continued until disappearance of symptoms of infl ammation shown by chest imaging.

Surgical approaches

Surgical approaches included transthoracic approach, either one incision (left transthoracic) or two incisions (Ivor-Lewis approach), or Mckeown approach (three stage esophagectomy and cervival anastomosis).The selection of which approach was based on the location of the lesions, the results of pulmonary function test, and the general status of the patients.None of patients with minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) was admitted to the ICU in the study period although MIE was introduced to our hospital in 2009.[11]

Postoperative respiratory tract management

Postoperative management of the respiratory tract included chest physiotherapy and early ambulation.And patient-controlled analgesia was given to every patient to control postoperative pain.Simple goal directed fluid therapy was used for postoperative fluid management, and the following four goals were considered: level of blood pressure, central venous pressure, urine output, and circulation of skin.[12]First, blood pressure (BP) was kept at normal level individually, i.e.at 100–110/60–70 mmHg for patients without a history of hypertension and at preoperative level for patients with a history of hypertension.Second, CVP level was kept at 8–12 cmH2O in our practice, which resembles conservative therapy in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).[13]Third, fluid volume was adjusted according to whether there is edema of skin.Finally, urine output was kept at more than 0.5 mL/(kg•hour).To achieve these goals, diuretic agents, fluid supplements or vasopressors were used to keep these four variables in the ranges mentioned above.

Groups

The patients were divided into two groups: postoperative major PCs group and no major PCs group.Postoperative major PCs were defined as respiratory insufficiency in need of ventilation, and pneumonia requiring antibiotic therapy.Pneumonia was defined according to the definition of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) surveillance definition.[14]Pathological staging was performed using the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Handbook (7thedition).[15]The operative mortality of the patients was defined as death within 30 days of esophagectomy.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS software for Windows, version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).Continuous variables were presented as mean±standard deviation and compared respectively using Student's t test.Categorical variables were reported as absolute numbers (frequency percentages) and analyzed using the Chi-square test.The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) was used to evaluate the ability of the model to discriminate between patients who developed postoperative PCs or not (discrimination).A two-tailed P value<0.05 was considered statistically signifi cant.

RESULTS

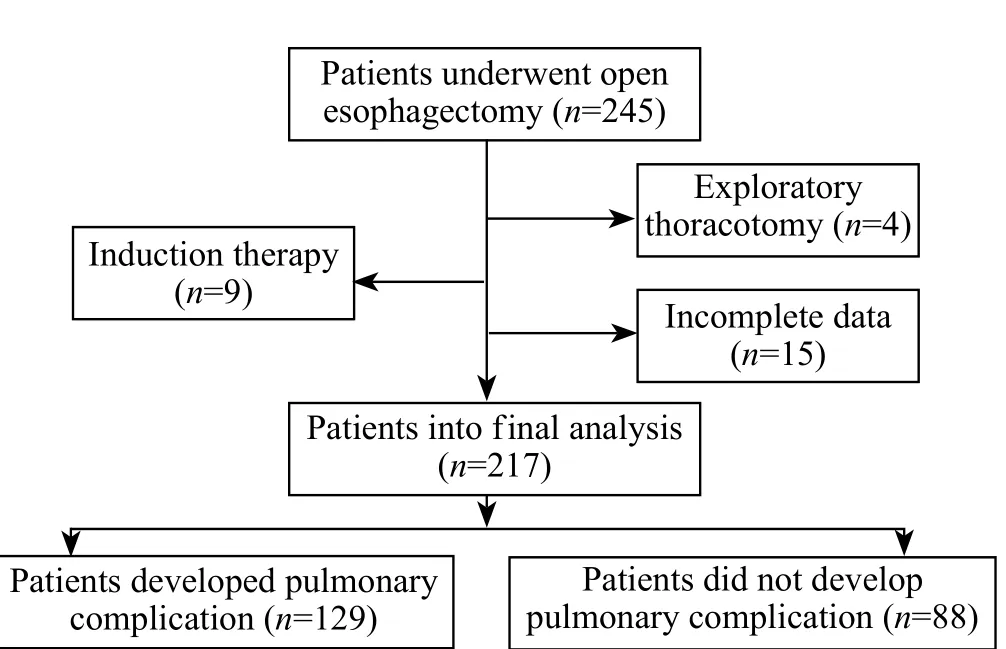

A total of 245 patients were admitted to the ICU during the study period.Twenty-eight patients were excluded including 4 patients who underwent exploratory thoracotomy, 9 patients who received induction therapy, and 15 patients with incomplete data.Thus, 217 patients were enrolled for the final analysis (Figure 1).Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are listed in Tables 1 and 2.No significant differences were seen in co-morbidities including hypertension, coronary heart diseases, diabetic mellitus, and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases in patients with or without major PCs.Other preoperative variables including age, performance status, FEV1% and DLCO% were also not significantly different between the two groups.Overall, 129 (59.4%) patients had postoperative major PCs and 13 (6.0%) patients died during the operation.Of the 129 patients, 106 were subjected to mechanical ventilation for more than 24 hours because of respiratory insufficiency, and 23 were given antibiotics because of pulmonary infection.Of the 13 patients, 7 died of septic shock caused by gastrointestinal fistula, 1 died of myocardial infarction, 1 died of cardiac arrest during intubation due to respiratory insuffi ciency, and 4 died of respiratory insufficiency induced by pulmonary infection.

Figure 1.Flowchart of the study.

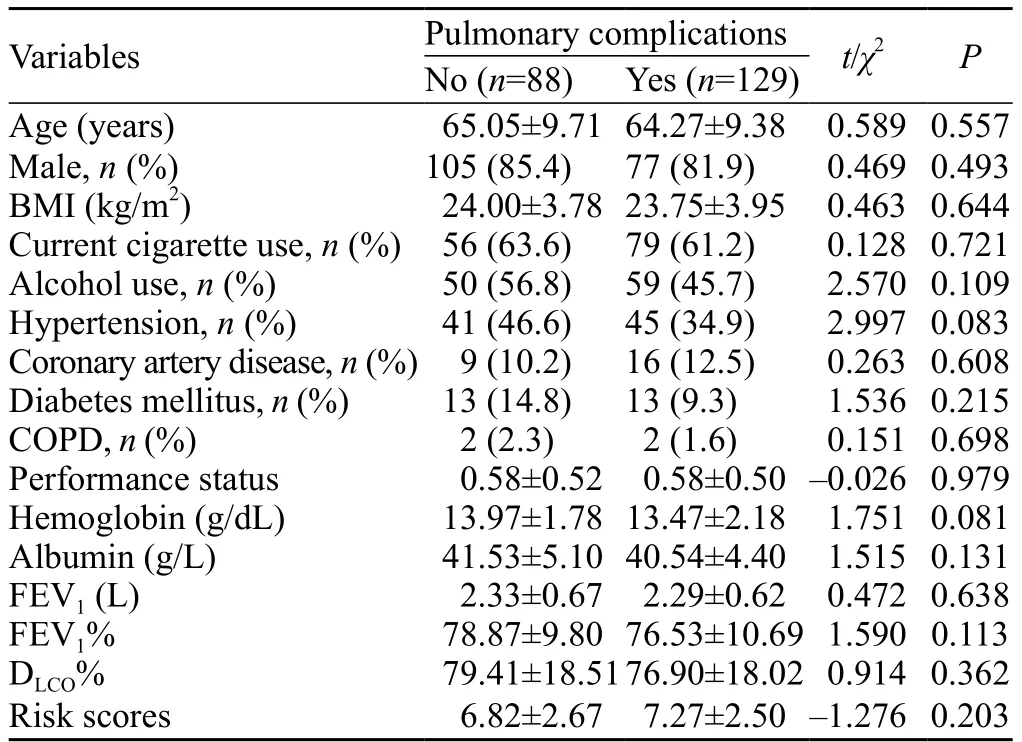

Table 1.Preoperative characteristics of patients who underwent esophagectomy

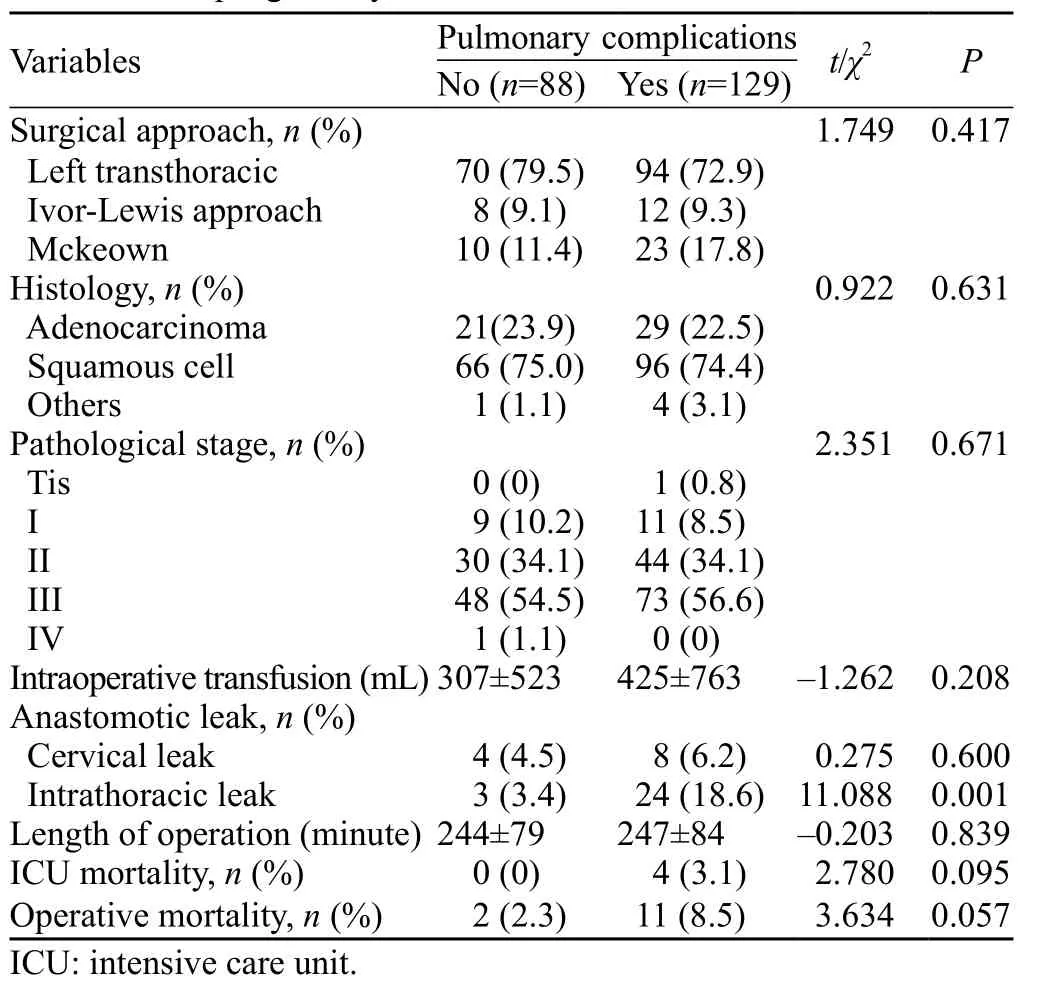

Table 2.Operative and postoperative characteristics of patients who underwent esophagectomy

The risk score of patients with major PCs was 7.27±2.50, which was higher than 6.82±2.67 of patients without postoperative PCs.However, there was no signifi cant difference between the two groups (P=0.203).Patients with postoperative intrathoracic anastomotic leak had more major PCs than did those without anastomotic leak (18.6% vs.3.4%; P=0.001).

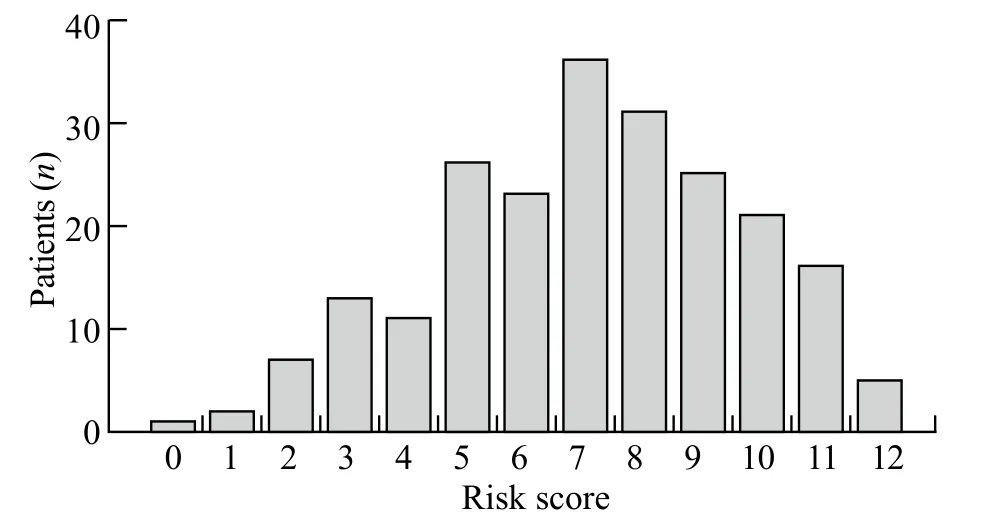

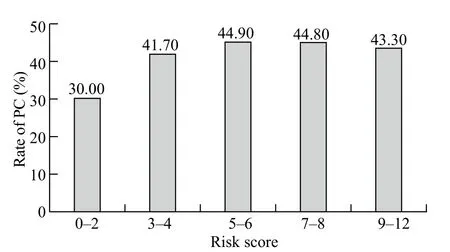

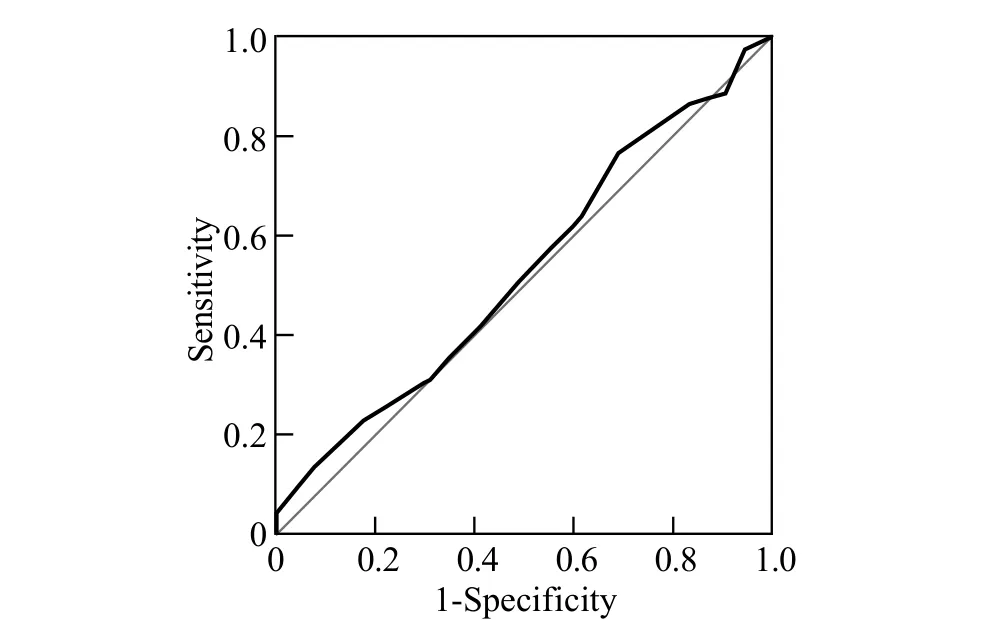

Risk scores varied from 0 to 12 in all patients (Figure 2).There was no significant difference in the incidenceof postoperative major PCs but there was an increment of risk scores (χ2=5.477, P=0.242; Figure 3).AUROC of the predictive score was 0.539±0.040 (P=0.324; 95% confidential interval 0.461 to 0.618) in predicting the occurrence of postoperative major PCs (Figure 4).

Figure 2.Distribution of risk scores in patients who underwent esophagectomy.

Figure 3.The incidence of pulmonary complications calculated according to risk scores grouped in quintiles.PC: pulmonary complications.

Figure 4.Receiver operator characteristic curve for risk score and pulmonary complications.Area under the curve=0.539±0.040 (P=0.324; 95%CI 0.461 to 0.618).

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrated that the predictive risk score proposed by Ferguson et al[3]was poor in predicting the occurrence of postoperative PCs in patients after esophagectomy for cancer.

The predictive score should be validated before clinical application.Ferguson et al[3]developed a predictive risk score in 2011 using the data of 516 patients who underwent esophagectomy.The scoring system based on four preoperative variables including age, FEV1%, DLCO% and PSscore predicted the occurrence of postoperative major PCs with an area under the curve of 70.8%.Postoperative major PCs in our study were defi ned as respiratory insuffi ciency in need of ventilation, pneumonia requiring antibiotic therapy, similar to the defi nition proposed by Ferguson et al,[3]which included respiratory insufficiency and pulmonary infiltrate requiring antibiotic therapy.Therefore, the method of our study was comparable to that of Ferguson et al's study.In the present study, however, the area under the curve of this predictive score was only 53.9%.We did not fi nd its sensitivity in predicting the risk of postoperative major PCs in our cohort.

In our study, age was not significantly different in univariate analysis of patients with or without postoperative PCs.Some tudies[3,7,8]found that age was an independent predictor for postoperative PC, but others found different results.[5,16,17]Zingg et al[16]reported that unlike age, preoperative co-morbidities were associated with increased pulmonary morbidity.Therefore, advanced age alone may not exclude esophagectomy for patients with esophageal cancer.[18]

Impaired preoperative pulmonary function has long been considered as an important tool for the evaluation of the risk of PCs after esophagectomy.[3,19,20]Avendano et al[19]and Shiozaki et al[20]reported that preoperative FEV1% less than 65% and 60% were associated with increased PCs after esophagectomy.But Ferguson et al[3]found that FEV1% an DLCO% could be used as independent predictors for postoperative PCs.In our study, however, both FEV1% and DLCO% were not significantly different in patients with or without postoperative PCs.In a study from our center,[21]69.3% of the patients with normal pulmonary function defined as FEV1% larger than that in 70% of the patients with postoperative respiratory insufficiency.Surgery-related complications such as anastomotic fistula played an important role in the development of postoperative respiratory insufficiency.Another study[22]revealed that postoperative anastomotic fistula was an independent risk factor for acute respiratory distress syndrome, a serious pulmonary complication after esophagectomy with a mortality rate of 50%.In our study, postoperativeanastomotic intrathoracic leak was found to be associated with an increased rate of postoperative PCs, which was consistent with the result of previous studies.[21–22]

Almost 1 500 esophagectomies were performed in our hospital annually and less than 50 patients who were admitted to the ICU directly from operation room were subjected to ventilation, other patients were transferred to wards after direct extubation.About 50 patients in the wards were admitted to the ICU mainly because of respiratory insuffi ciency after esophagectomy.Thus, the proportion of PCs was over 50% in the ICU, which was higher than 10%–20% reported in the literature.[2–3,5,8]

Currently, many studies have investigated the risk factors of esophagectomy.[2,5,8]But only Ferguson et al developed a scoring system for predicting the risk of complication after esophagectomy and validated it in patients.[3,9]

There are some limitations to this study.First, we excluded the patients who received induction therapy such as chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy.Induction therapy may decrease FEV1% and DLCO%, thereby increasing the risk of postoperative PCs.However, a recent study[23]did not find an increased rate of PCs in patients who received neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy compared with those who did not receive neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy.Therefore, exclusion of patients who received induction may not influence the result of this study.Second, only 217 patients were enrolled in the study, so it is difficult to draw a conclusion.However, the number of patients in our study was more than 150, which made the result of this study credible.Third, the retrospective nature of this study may be related to the completeness of data.However, we excluded the patients who had incomplete data making the results of this study believable.

In summary, in this cohort the predictive risk score for postoperative PCs was not accurate in discriminating patients with or without postoperative PCs after esophagectomy for cancer.Other factors such as anastomotic leak were associated with an increased rate of major PCs.

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cancer Hospital of CAMS and PUMC.It was therefore performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments.Patients' consents were waived because of the observational nature of this study.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that there are no confl icts of interest related to the publication of this paper.

Contributors: Xing XZ proposed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the fi rst draft.All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts.

REFERENCES

1 Mamidanna R, Bottle A, Aylin P, Faiz O, Hanna GB.Shortterm outcomes following open versus minimally invasive esophagectomy for cancer in England: a population-based national study.Ann Surg 2012; 255: 197–203.

2 Wright CD, Kucharczuk JC, O'Brien SM, Grab JD, Allen MS; Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database.Predictors of major morbidity and mortality after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: a society of thoracic surgeons general thoracic surgery database risk adjustment model.J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009; 137: 587–596.

3 Ferguson MK, Celauro AD, Prachand V.Prediction of major pulmonary complications after esophagectomy.Ann Thorac Surg 2011; 91: 1494–1501.

4 Xing XZ, Gao Y, Wang HJ, Yang QH, Huang CL, Qu SN, et al.Risk factors and prognosis of critically ill cancer patients with postoperative acute respiratory insufficiency.World J Emerg Med 2013; 4: 43–47.

5 Yoshida N, Watanabe M, Baba Y, Iwagami S, Ishimoto T, Iwatsuki M, et al.Risk factors for pulmonary complications after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer.Surg Today 2014; 44: 526–532.

6 Molena D, Mungo B, Stem M, Feinberg RL, Lidor AO.Outcomes of esophagectomy for esophageal achalasia in the United States.J Gastrointest Surg 2014; 18: 310–317.

7 Kinugasa S, Tachibana M, Yoshimura H, Ueda S, Fujii T, Dhar DK, et al.Postoperative pulmonary complications are associated with worse short- and long-term outcomes after extended esophagectomy.J Surg Oncol 2004; 88: 71–77.

8 Law S, Wong KH, Kwok KF, Chu KM, Wong J.Predictive factors for postoperative pulmonary complications and mortality after esophagectomy for cancer.Ann Surg 2004; 240: 791–800.

9 Reinersman JM, Allen MS, Deschamps C, Ferguson MK, Nichols FC, Shen KR, et al.External validation of the Ferguson pulmonary risk score for predicting major pulmonary complications after oesophagectomy.Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2015 Feb 26.pii: ezv021.[Epub ahead of print]

10 Mu J, Gao S, Mao Y, Xue Q, Yuan Z, Li N, et al.Open threestage transthoracic oesophagectomy versus minimally invasive thoraco-laparoscopic oesophagectomy for oesophageal cancer: protocol for a multicentre prospective, open and parallel, randomised controlled trial.BMJ Open 2015; 17; 5: e008328.

11 Mu J, Yuan Z, Zhang B, Li N, Lyu F, Mao Y, et al.Comparative study of minimally invasive versus open esophagectomy for esophageal cancer in a single cancer center.Chin Med J (Engl) 2014; 127: 747–752.

12 Xing X, Gao Y, Wang H, Qu S, Huang C, Zhang H, et al.Correlation of fluid balance and postoperative pulmonary complications in patients after esophagectomy for cancer.J Thorac Dis 2015; 7: 1986-93.

13 Wiedemann HP, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Thompson BT, Hayden D, deBoisblanc B, et al.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network.Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury.N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 2564–2575.

14 Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA.CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specifi c types of infections in the acute care setting.Am J Infect Control 2008; 36: 309–332.

15 Rice TW, Blackstone EH, Rusch VW.7th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: esophagus and esophagogastric junction.Ann Surg Oncol 2010; 17: 1721–1724.

16 Zingg U, Smithers BM, Gotley DC, Smith G, Aly A, Clough A, et al.Factors associated with postoperative pulmonary morbidity after esophagectomy for cancer.Ann Surg Oncol 2011; 18: 1460–1468.

17 Masoomi H, Nguyen B, Smith BR, Stamos MJ, Nguyen NT.Predictive factors of acute respiratory failure in esophagectomy for esophageal malignancy.Am Surg 2012; 78: 1024–1028.

18 Ruol A, Portale G, Zaninotto G, Cagol M, Cavallin F, Castoro C, et al.Results of esophagectomy for esophageal cancer in elderly patients: age has little influence on outcome and survival.J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007; 133: 1186–1192.

19 Avendano CE, Flume PA, Silvestri GA, King LB, Reed CE.Pulmonary complications after esophagectomy.Ann Thorac Surg 2002; 73: 922–926.

20 Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Okamura H, Murayama Y, Komatsu S, Kuriu Y, et al.Risk factors for postoperative respiratory complications following esophageal cancer resection.Oncol Lett 2012; 3: 907–912.

21 Mao YS, Zhang DC, He J, Zhang RG, Cheng GY, Sun KL, et al.Postoperative respiratory failure in patients with cancer of esophagus and gastric cardia (Article in Chinese).Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 2005; 27: 753–756.

22 Tandon S, Batchelor A, Bullock R, Gascoigne A, Griffin M, Hayes N, et al.Peri-operative risk factors for acute lung injury after elective oesophagectomy.Br J Anaesth 2001; 86: 633–638.

23 Gronnier C, Tréchot B, Duhamel A, Mabrut JY, Bail JP, Carrere N, et al.Impact of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy on postoperative outcomes after esophageal cancer resection: results of a European multicenter study.Ann Surg 2014; 260: 764–770; discussion 770–771.

Received August 26, 2015

Accepted after revision December 20, 2015

BACKGROUND: Esophagectomy is a very important method for the treatment of resectable esophageal cancer, which carries a high rate of morbidity and mortality.This study was undertaken to assess the predictive score proposed by Ferguson et al for pulmonary complications after esophagectomy for patients with cancer.

METHODS: The data of patients who admitted to the intensive care unit after transthoracic esophagectomy at Cancer Hospital of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College between September 2008 and October 2010 were retrospectively reviewed.

RESULTS: Two hundred and seventeen patients were analyzed and 129 (59.4%) of them had postoperative pulmonary complications.Risk scores varied from 0 to 12 in all patients.The risk scores of patients with postoperative pulmonary complications were higher than those of patients without postoperative pulmonary complications (7.27±2.50 vs.6.82±2.67; P=0.203).There was no significant difference in the incidence of postoperative pulmonary complications as well as in the increase of risk scores (χ2=5.477, P=0.242).The area under the curve of predictive score was 0.539±0.040 (95%CI 0.461 to 0.618; P=0.324) in predicting the risk of pulmonary complications in patients after esophagectomy.

CONCLUSION: In this study, the predictive power of the risk score proposed by Ferguson et al was poor in discriminating whether there were postoperative pulmonary complications after esophagectomy for cancer patients.

Corresponding Author:Xue-zhong Xing, Email: xingxzh2000@aliyun.com

DOI:10.5847/wjem.j.1920–8642.2016.01.008

World journal of emergency medicine2016年1期

World journal of emergency medicine2016年1期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Airway foreign bodies: A critical review for a common pediatric emergency

- End-tidal capnometry during emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia: a randomized, controlled study

- Intranasal ketamine for the treatment of patients with acute pain in the emergency department

- Analgesic effect of paracetamol combined with lowdose morphine versus morphine alone on patients with biliary colic: a double blind, randomized controlled trial

- Comparison of intravenous pantoprazole and ranitidine in patients with dyspepsia presented to the emergency department: a randomized, double blind, controlled trial

- A correlation analysis of Broselow™ Pediatric Emergency Tape-determined pediatric weight with actual pediatric weight in India