中国儿童肝移植临床诊疗指南(2015版)

中华医学会器官移植学分会 中国医师协会器官移植医师分会

·标准与指南·

中国儿童肝移植临床诊疗指南(2015版)

中华医学会器官移植学分会 中国医师协会器官移植医师分会

1 前 言

儿童肝移植是临床肝移植的重要组成部分。自1963年世界首例儿童肝移植手术实施以来,经过半个世纪的发展,儿童肝移植的术后生存率已得到极大提高。在美国、日本等发达国家,儿童肝移植比例均超过肝移植总例数的10%,术后5年生存率约为80%,儿童活体肝移植的生存率则更高[1-2]。目前,国外儿童肝移植方面的指南有美国肝病研究协会与美国移植协会共同发布的《2013年儿童肝移植术后长期医疗管理指南》[3]和《2014年儿童肝移植术前评估指南》[4]。

中国大陆地区儿童肝移植的开展起步较晚,但近年来发展迅速。大陆地区在1996年成功实施了首例儿童肝移植。截至2013年12月31日,中国肝移植注册(China Liver Transplant Registry,CLTR)系统登记的18岁以内的儿童肝移植为935例,占大陆地区肝移植总数的3.6%。目前,儿童肝移植已逐渐在全国范围内广泛实施,亟待相关临床实践指南来指导全国儿童肝移植工作更规范、安全、有效地开展。中华医学会器官移植学分会、中国医师协会器官移植医师分会组织专家制订了《中国儿童肝移植临床诊疗指南(2015版)》(以下简称“指南”),以期为我国儿童肝移植工作的规范化开展提供指引。

2 指南参照的推荐级别/证据水平标准

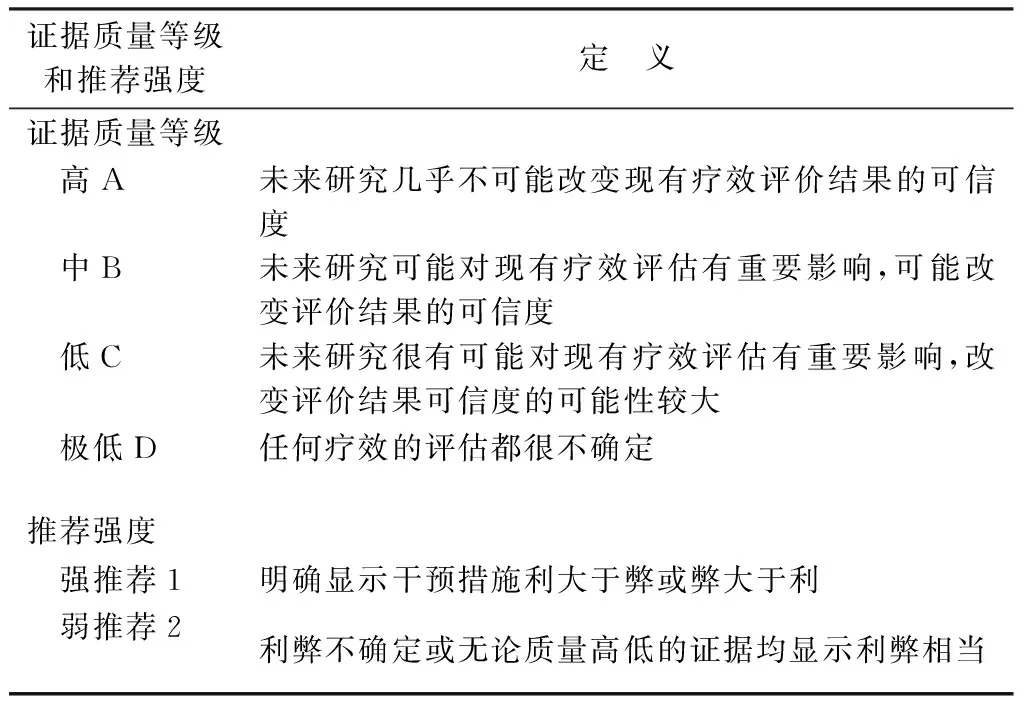

本指南按照“推荐分级的评估、制定与评价(GRADE)”系统对证据质量等级和推荐强度进行分级(见表1)。

表1 GRADE系统证据质量等级和推荐强度[5]

3 临床问题及推荐

3.1 儿童肝移植适应证和禁忌证(见表2,3)

表2 儿童肝移植适应证[2,4,6-8]

推荐意见:

1.儿童肝移植的适应证应结合患儿的临床表现、疾病严重程度、肝外器官受累情况以及其他治疗手段的疗效综合判定(1-A)。

表3 儿童肝移植禁忌证[4, 8-9]

推荐意见:

2. 若肝母细胞瘤的肺转移灶在化疗后完全消失或单发肺转移灶经根治性手术切除,则不被视为肝移植的禁忌证(1-B)。

3. 门脉性肺动脉高压患儿应尽快接受肝移植评估(2-B),且移植前应将肺动脉压力控制在35 mmHg (1 mmHg=0.133 kPa,下同)以内;药物控制无效的肺动脉高压为肝移植的相对禁忌证(1-B)。

4. 肝移植无法改善C型尼曼匹克病进行性加重的神经系统症状,故为肝移植的绝对禁忌证(1-B)。

5. Alper′s综合征或丙戊酸钠诱导的肝衰竭常合并严重的肝外病变,故不适合行肝移植手术(1-B)。

6. 噬血细胞性淋巴组织细胞增多症引起的急性肝功能衰竭应首选化疗或骨髓移植(2-B)。

3.2 儿童肝移植的术前准备与评估

3.2.1 儿童肝移植的术前多学科评估团队[4, 8]

儿童肝移植术前评估团队应涵盖所有相关学科,包括移植外科、小儿外科或儿童肝脏科、营养科、感染科、重症医学科、麻醉科、移植协调员、精神医学科、监护人、社会工作者等。参与评估的各学科医疗成员应擅长儿科疾病的临床诊疗。

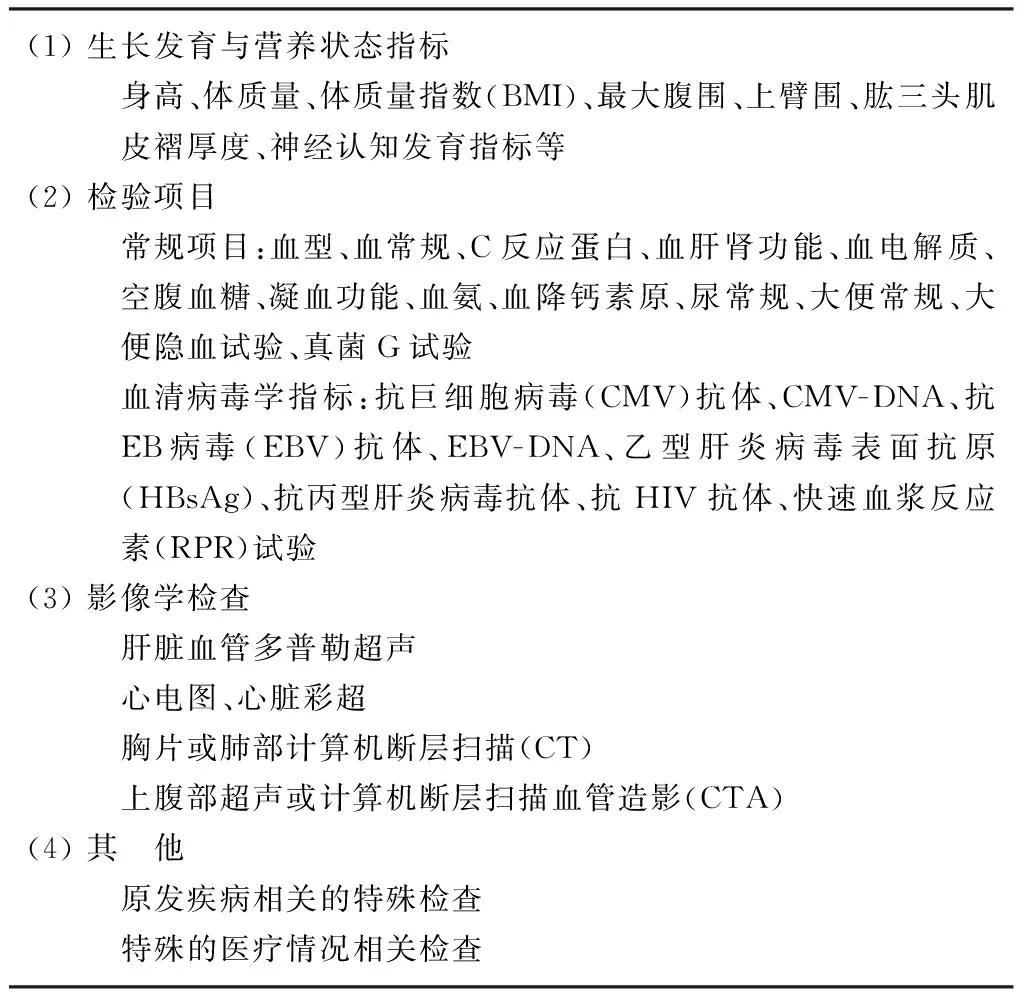

3.2.2 儿童肝移植术前的主要检查项目(见表4)

3.2.3 终末期肝病的严重程度评估[10]

终末期肝病模型(model for end-stage liver disease,MELD)评分仅适用于年满12周岁的儿童或成人肝病患者的疾病严重程度评估。儿童终末期肝病(pediatric end-stage liver disease,PELD)评分是评价12周岁以内儿童的疾病严重程度最常用的参数。

表4 肝移植前检查项目

PELD评分的计算公式为:

PELD评分=4.36[年龄(<1周岁)]-6.87×Loge(血清白蛋白,g/dL)+4.80×Loge(血清总胆红素,mg/dL)+18.57×Loge[国际标准化比值(INR)]+6.67[生长发育不良(<-2倍标准差)]

注:(1)若血清白蛋白(g/dL)、总胆红素(mg/dL)或INR的数值小于1,则直接将其设为1后进行计算;(2)若患儿在登记肝移植时未满1周岁,则其在2周岁以前的PELD评分均需加上4.36;(3)生长发育不良是指身高低于相同年龄、性别的儿童身高中位数的2倍标准差以下;(4)计算所得的PELD评分需以整数表示。

推荐意见:

7. 推荐使用PELD评分(<12周岁)与MELD评分(≥12周岁)来评定儿童终末期肝病的严重程度,尸体器官应优先分配给PELD评分较高的患儿(1-B);少数疾病严重程度与PELD/MELD评分不符的病例应校正评分后重新进入肝移植等待名单(1-B)。

3.2.4 重要脏器功能评估

移植前应对患儿的心肺功能、肾脏功能、营养状态、神经认知发育等情况进行综合评估。在心肺功能评估中,应重视对门-体循环分流患儿的门脉性肺动脉高压或肝肺综合征的评估[11-13],以及对囊性纤维化患儿的呼吸功能评估[14]。肾小球滤过率(glomerular filtration rate,GFR)是目前公认的评价肾功能最准确的指标,但是直接测定GFR价格昂贵、程序繁琐,而且不能完全排除对患者的危害。改良的Schwartz公式[15][GFR估计值=0.413×身高(cm)/血清肌酐值(mg/dL)]计算的GFR估计值[mL·min-1·(1.73 m2)-1]或血清胱抑素C值[4, 16-17]可用于评估GFR的变化水平。另外,合理地评估与纠正患儿的营养不良[18-20]与神经认知发育障碍[21-22]也是移植前评估的重要内容。

推荐意见:

8. 儿童肝移植前应行超声心动图检查(2-B);若超声心动图显示右心室收缩压高于50 mmHg,可进一步行右心导管检查以排除门脉性肺动脉高压(2-B)。

9. 对于可能存在门-体循环分流的患儿应在直立位行血氧饱和度测定(2-B);囊性纤维化患儿应在移植前行肺功能检查(2-B)。

10. 儿童肝移植前应行肾功能测定(1-A);可使用改良Schwartz公式(2-C)或血清胱抑素C测定(2-B)间接评估GFR水平;不推荐使用血清肌酐值直接评价肾功能状态(1-B)。

11. 对于营养不良的患儿,应给予针对性的营养支持,必要时通过胃管或肠外营养途径补充营养(2-B)。

12. 胆汁淤积性肝病患儿应注意补充中链脂肪酸与蛋白质(排除肝性脑病)(2-B),同时可适当补充脂溶性维生素(2-B),尤其对于INR延长的患儿可经静脉补充维生素K(2-C)。

13. 术前应对患儿进行神经认知发育测试(2-C),对于神经认知发育不良的患儿应查明原因并尽早接受治疗(1-B)。

3.3 儿童肝移植的手术时机

3.3.1 胆道闭锁与其他胆汁淤积性肝病[4, 8, 23-26]

(1)肝硬化导致肝功能失代偿;

(2)胆道闭锁葛西术(又称Kasai术)后3~6个月血清胆红素仍高于34 μmol/L;

(3)胆道闭锁葛西术后门脉高压导致难以控制的反复消化道出血或顽固性腹水等并发症;

(4)胆道闭锁葛西术后无法控制的反复胆管炎发作;

(5)严重的生长发育障碍,体质量与身高低于同龄、同性别儿童的第3百分位水平。

推荐意见:

14. 出生60 d以内的胆道闭锁患儿的初始外科治疗应首选葛西术(1-B),若患儿葛西术后3~6个月总胆红素仍高于100 μmol/L,则需尽快行肝移植手术;葛西术后总胆红素介于34~100 μmol/L之间(1-B)、难以控制的门脉高压症状(2-B)或反复胆管炎发作(2-B)的患儿也应考虑行肝移植评估。

15. 未行葛西手术的患儿若出现肝硬化失代偿可直接行肝移植手术(2-B)。

3.3.2 代谢性疾病[8, 27-28]

(1)预期将出现危及生命或严重影响生活质量的并发症,且经饮食与药物无法控制或得不到有效治疗;

(2)代谢紊乱可引起严重的神经系统并发症,且无其他有效治疗手段;

(3)经内科治疗无效的肝硬化失代偿。

推荐意见:

16. 代谢性疾病常合并肝外器官病变,其肝移植时机应根据不同疾病的特点个体化判断(1-A)。

3.3.3 暴发性肝功能衰竭[4, 29-30]

肝脏损伤单元(liver injury units, LIU)评分可用于指导儿童暴发性肝衰竭的手术时机选择(见表5),计算公式如下:

(1) LIU评分(PT)=3.584×总胆红素峰值(mg/dL)+1.809×凝血酶原时间峰值(s)+0.307×血氨峰值(μmol/L);

(2) LIU评分(INR)=3.507×总胆红素峰值(mg/dL)+54.51×INR峰值+0.254×血氨峰值(μmol/L)。

表5 儿童暴发性肝功能衰竭的肝移植手术时机[29-30]

注: 本表适用于18岁以内的暴发性肝衰竭患者,LIU评分(PT)与LIU评分(INR)二者可任选其一; LIU.肝脏损伤单元; PT.凝血酶原时间; INR.国际标准化比值

推荐意见:

17. 对于暴发性肝功能衰竭应及时联系儿童肝移植中心行多学科评估(1-B),并在暴发性肝功能衰竭的病因明确后充分评估肝移植的必要性及是否存在肝移植的禁忌证(1-B)。

18. 可考虑使用LIU评分系统指导儿童暴发性肝功能衰竭的手术时机选择(1-C)。

3.3.4 肝脏肿瘤[31-32]

(1)术前评估显示手术无法根治切除但无明显血管侵犯的非转移性肝细胞癌;

(2)无法手术切除、其他治疗方式亦无效的非转移性的其他肝脏肿瘤。

推荐意见:

19. 米兰标准不适用于儿童肝癌肝移植,故儿童肝癌行肝移植的指征不应受限于肿瘤大小或数目(2-B)。

3.4 儿童肝移植的手术方式[33-41]

儿童肝移植的手术方式主要分为全肝移植和部分肝移植。全肝移植包括经典原位肝移植与背驼式原位肝移植;部分肝移植包括活体肝移植、劈离式肝移植与减体积肝移植,此类技术可选择的供肝类型有左外叶、带或不带尾状叶的左半肝、带或不带肝中静脉的左半肝、带或不带肝中静脉的右半肝、右后叶、减体积的左外叶或单段移植物(Ⅱ或Ⅲ段)。此外,对于某些特殊的疾病还可选择多米诺肝移植与辅助性肝移植。

推荐意见:

20. 在全肝移植中,若供、受者的下腔静脉管径不匹配,则应优先考虑行背驼式肝移植(2-C)。

21. 对于左外叶供肝体积与受者体质量明显不匹配的婴幼儿部分肝移植,应考虑将移植物体积进行削减后再植入受者体内(1-B)。

22. 应优先选择与受者具有相同或相容血型的供者,但是1周岁以内的儿童在无合适的血型相容供者时可选择性实施血型不相容活体肝移植(1-C)。

23. 对于抗ABO血型抗体滴度较高或大龄患儿的血型不相容活体肝移植,可考虑使用血浆置换(2-C)、抗CD20单克隆抗体(如利妥昔单抗)(2-C)、联合术中脾脏切除(2-D)等措施,对提高移植物生存率有一定作用。

24. 离体状态下的供肝劈离技术可能对供肝质量造成一定损害,因此此类供肝的冷缺血时间应尽量控制在10 h以内(2-C),供肝重量与受者体质量比值(GRWR)应尽量达到1.2%以上(1-C)。

25. 多米诺肝移植的供肝本身存在病变,因此将其移植给其他受者时应谨慎评估供肝病变可能产生的不利影响(1-B)。

26. 辅助性肝移植的主要适应证为非肝硬化性代谢性疾病(1-C)与暴发性肝衰竭(1-C)。

3.5 儿童肝移植常见并发症的预防与处理

3.5.1 血管并发症

(1)动脉并发症[3, 42-45]

最常见的动脉并发症为肝动脉血栓,常引起缺血性胆道并发症,后者是术后移植物失功的主要原因之一。多普勒超声是肝动脉血栓的首选监测手段,动脉开放后应立即行多普勒超声观察动脉血流情况,并在术后定期复查。若出现肝动脉血流异常,需立即行数字减影血管造影或急诊手术予以明确。肝动脉血栓的治疗方式包括急诊手术取栓与动脉再通、经静脉注射药物溶栓治疗、放射介入下溶栓治疗、再次肝移植等。其他的动脉并发症包括肝动脉狭窄、肝动脉假性动脉瘤等。

推荐意见:

27. 多普勒超声是动脉并发症的重要监测手段,动脉阻力指数<0.6需警惕肝动脉血栓的发生风险(1-C)。

28. 早期肝动脉血栓首选的治疗方式为急诊手术取栓与动脉再通(2-C);肝动脉血栓继发的弥散性缺血性胆道并发症通常需行再次肝移植(1-B)。

29. 若肝动脉血栓形成后建立了良好的侧枝循环,患儿肝功能正常且一般情况稳定,则暂可不予处理(2-C)。

(2)门静脉并发症[3, 46-48]

主要包括门静脉血栓和门静脉狭窄。门静脉血栓形成为肝移植术后的严重并发症,术后早期的门静脉血栓形成可导致急性肝功能恶化,后期的门静脉血栓因侧枝循环的建立通常以门脉高压症状为主要表现。多普勒超声是首选的诊断方法,常用的治疗手段包括手术取栓、血管架桥、溶栓治疗、放射介入下支架置入等。门静脉狭窄常发生于门静脉吻合口处,多与吻合缝线收缩过紧、门静脉扭曲或成角等技术性因素有关。术中发现的门静脉狭窄需拆除原吻合口重新吻合;术后门静脉狭窄可通过放射介入手段行球囊扩张或放置内支架。

推荐意见:

30. 门静脉血栓引起肝功能恶化需立即实施手术或其他治疗方式,尽快恢复门静脉血流(1-C)。

31. 后期门静脉血栓引起的门脉高压的治疗与非移植后的门脉高压治疗相似,必要时需行再次肝移植(1-C)。

32. 门静脉血栓患儿若存在血管异常不适合重建或发生急性肝功能衰竭,则再次肝移植是唯一的治疗选择(1-C)。

(3)流出道梗阻[49-50]

包括下腔静脉梗阻、肝静脉回流障碍、架桥血管回流障碍等。梗阻的发生常与流出道狭窄、扭曲成角、血栓形成等因素有关。临床表现为腹水增多、低蛋白血症、腹泻等。术后应行多普勒超声动态监测流出道直径与最大流速。若由于移植物位置不佳导致肝静脉扭曲可重建镰状韧带和圆韧带固定移植物(左叶供肝);术后发现的肝静脉吻合口狭窄可通过介入治疗置入金属支架扩张并支撑。

推荐意见:

33. 多普勒超声为首选的诊断方式,若诊断困难可行肝静脉造影术明确(1-B);经介入支架置入术是首选的治疗方式(1-B)。

3.5.2 胆道并发症

(1)胆瘘[51-52]

主要包括胆道吻合口瘘与肝切面胆瘘,一般发生于术后早期,在部分肝移植中的发生率高于全肝移植。胆瘘发生时,腹腔引流管常可见胆汁样液体流出,如胆汁引流不畅或引流管已拔除,则可出现腹肌紧张、腹痛、发热等临床表现。引流液检测、腹部超声、CT或磁共振胰胆管成像(magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, MRCP)可协助诊断。大多数胆瘘可通过腹腔引流或经内镜逆行胰胆管造影(endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancretography,ERCP)放置鼻胆管引流等方法予以治愈。非手术治疗无效者需接受手术治疗。

推荐意见:

34. 胆瘘可先采用非手术治疗,ERCP适用于胆管端端吻合后发生的胆瘘(1-B);如非手术治疗无效,可采用手术方式治疗(1-B)。

(2)胆道狭窄[3, 51-54]

包括吻合口狭窄与非吻合口狭窄,可行超声或MRCP予以诊断。相较于胆管-空肠吻合,胆管端端吻合术后胆道狭窄发生风险较高。ERCP置入支架内支撑治疗胆管端端吻合口狭窄通常可获得较好的疗效;对于胆管-空肠吻合口狭窄或ERCP治疗困难的端端吻合口狭窄可行经皮肝穿刺胆道引流,必要时需再次手术解除胆道梗阻。由于肝内胆管缺血引起的弥漫性非吻合口狭窄需行再次肝移植术。

推荐意见:

35. 胆管端端吻合后的单纯性吻合口狭窄首选ERCP置入内支架(1-B),ERCP治疗困难者可选择再次手术拆除原吻合口并改为Roux-en-Y胆管-空肠吻合(2-C)。

3.5.3 感染性并发症

(1)巨细胞病毒(cytomegalovirus,CMV)感染[3, 55-58]

儿童肝移植术后最常见的感染类型之一,临床表现无特异性,可出现发热、乏力、白细胞减少、转氨酶升高等症状。CMV-DNA阳性、PP65抗原阳性或新发的CMV-IgM阳性可诊断为CMV感染。接受抗CMV+供肝而自身抗CMV为阴性的患儿是术后CMV感染的高危人群;使用过高剂量的免疫抑制剂也会明显增加CMV感染风险。移植后预防性抗病毒治疗可显著减低CMV感染率。更昔洛韦与缬更昔洛韦是抗CMV感染最有效的药物,其他二线用药包括膦甲酸、西多福韦、抗CMV免疫球蛋白等。

推荐意见:

36. 抗CMV-IgG供者+/受者-的高危患儿术后应接受至少3个月的预防性抗病毒治疗,术后14 d内使用静脉注射更昔洛韦,14 d后改为口服更昔洛韦或缬更昔洛韦(1-B)。

37. CMV感染的首选治疗为静脉注射更昔洛韦,治疗应持续至血液CMV-DNA转阴(1-C)。

38. 难治性病例(静脉注射更昔洛韦2周无效)可使用二线用药,同时应行耐药突变基因检测(2-D)。

(2)EB病毒(Epstein-Barr virus,EBV)感染与移植后淋巴增殖性疾病(posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder, PTLD)[59-62]

对于大多数PTLD,EBV感染在其发病上起着关键性作用。PTLD在移植术后1年内较常见,且多见于5岁以内患儿,其在儿童肝移植术后的发病率约为3%,死亡率达12%~60%。对于术后不明原因发热、淋巴结肿大的患儿,PTLD的诊断需结合组织病理学结果或其他检查(如EBV-DNA)予以明确。PTLD的主要治疗手段为降低免疫抑制剂用量、静脉注射免疫球蛋白和抗CD20单克隆抗体,其他治疗还包括化疗、放疗、手术等。

推荐意见:

39. 对于抗EBV抗体供者+/受者-的患儿术后应定期监测EBV-DNA与血清抗EBV抗体(1-B)。

40. 降低免疫抑制剂剂量应作为PTLD的初始治疗(1-B);对于CD20表达阳性的PTLD患儿,可考虑选择抗CD20单克隆抗体(2-C)。

(3)新发乙型肝炎病毒(hepatitis B virus,HBV)感染[63-65]

移植后新发HBV感染多见于接受乙肝核心抗体阳性(抗HBc+)供肝但自身抗HBc为阴性的患儿。移植后预防性抗HBV治疗可显著降低此类患儿新发HBV感染的发生率。儿童肝移植术后新发HBV的治疗与慢性乙型肝炎患儿相似,用药方案应根据患儿的年龄与体质量作出合适的选择。

推荐意见:

41. 抗HBc+供肝患儿术后应监测HBV病毒学指标(1-A),且术后应使用核苷类药物行预防性抗HBV治疗(1-C),并适时接种乙肝疫苗(1-C)。

42. 移植后HBV感染并出现病毒耐药的患儿需行HBV变异检测(2-C)。

(4)真菌感染[66]

术后真菌感染可见于各种类型的儿童肝移植,严重的侵袭性真菌感染甚至会危及患儿生命。对于供者感染风险较高(如重症监护病房暴露时间较长)的尸体肝移植受者,术后可行预防性抗真菌治疗。感染后的抗真菌治疗方案应根据药敏试验结果予以选择。

3.5.4 排斥反应

(1)急性排斥反应[3, 67]

最常见的排斥反应类型,大多发生在移植后3个月内,术后7~14 d最为多见。术后血清转氨酶、总胆红素、碱性磷酸酶和/或γ-谷氨酰转移酶升高伴免疫抑制剂浓度偏低常提示急性排斥反应,必要时需行肝穿刺活检予以明确。轻度急性排斥反应者可增加钙调神经磷酸酶抑制剂(calcineurin inhibitor,CNI)剂量或加用麦考酚酸类药物;如加药后效果仍不理想,可考虑更换CNI种类。若转氨酶升高持续1周以上或出现明显肝功能异常,可行糖皮质激素冲击治疗。

推荐意见:

43. 大多数急性排斥反应可通过肝功能变化与免疫抑制剂浓度监测进行判定(1-C),但是肝穿刺活检仍然是诊断急性排斥反应的“金标准”(1-A)。

(2)慢性排斥反应[68]

是影响移植物长期生存的重要因素之一,在存活超过5年的患儿中发生率约为5%。其治疗与急性排斥反应相似,部分反复治疗无效者需接受再次肝移植。

(3)移植物抗宿主病(graft-versus-host disease,GVHD)[69]

肝移植术后GVHD较罕见,但致死率很高,临床表现为不明原因发热、腹泻、皮疹、白细胞减少等。结合特征性的临床表现、皮肤组织病理学表现、嵌合体检测等有助于诊断的确立。肝移植术后GVHD尚无理想的治疗方法,已报道的治疗手段包括糖皮质激素、减少免疫抑制剂用量、抗淋巴细胞免疫球蛋白、白介素-2受体拮抗剂等。

3.5.5 原发性移植物无功能

常表现为肝移植术后数小时或数日内(一般不超过2周)严重的肝功能异常,多与供肝质量差、缺血再灌注损伤、冷缺血时间过长等因素有关,是肝移植术后最严重的并发症。再次肝移植是唯一的治疗选择。

3.6 儿童肝移植的长期管理与随访

3.6.1 免疫抑制用药及相关问题

(1)免疫抑制治疗方案[3, 67, 70-74]

首选以CNI类药物(他克莫司或环孢素)为基础且包含糖皮质激素的免疫抑制治疗方案。他克莫司的初始剂量为0.1~0.15 mg·kg-1·d-1,目标血药浓度在第1个月内为8~12 ng/mL,第2~6个月为7~10 ng/mL,第7~12个月为5~8 ng/mL,12个月以后根据肝功能情况酌情维持在5 ng/mL左右。环孢素的初始剂量为6~10 mg·kg-1·d-1,目标血药浓度在第1个月内C0为150~200 ng/mL,C2为1 000~1 200 ng/mL,第2~6个月C0为120~150 ng/mL,C2为800~1 000 ng/mL,第7~12个月C0为100~120 ng/mL,C2为500~800 ng/mL,12个月以后根据肝功能情况酌情将C0维持在100 ng/mL左右,将C2维持在500 ng/mL左右。若CNI血药浓度偏低且增加CNI剂量后仍无法达到目标浓度,可加用麦考酚酸类药物或更换CNI种类。首剂糖皮质激素应在术中无肝期一次性静脉注射(甲泼尼龙10 mg/kg),术后第1天静脉注射糖皮质激素的剂量为4 mg·kg-1·d-1,随后每日逐步减量至术后1周更换为口服糖皮质激素(例如泼尼松,初始剂量0.25~1 mg·kg-1·d-1)。另外,使用含白介素-2受体拮抗剂的免疫诱导方案不仅可减少糖皮质激素的使用剂量,还有利于降低排斥反应的发生率;若使用免疫诱导,则CNI和糖皮质激素的使用剂量和时间可作适当调整。

推荐意见:

44. 接受肝移植的患儿应尽早撤除激素,建议通常在术后3~6个月内停用糖皮质激素(1-C)。

45. 细胞色素P450 3A5基因型检测有助于指导移植后免疫抑制方案(2-C)。

(2)免疫耐受与撤药[75-76]

肝脏是“免疫特惠”器官,约10%~20%的肝移植患者术后可发生免疫耐受并可逐渐撤除免疫抑制剂。儿童的免疫系统尚未发育成熟,更易诱导免疫耐受的发生。但是,术后完全撤除免疫抑制剂目前仅局限于临床试验。

(3)免疫抑制剂相关不良反应

长期使用CNI类药物或糖皮质激素可引起肾功能损伤、心血管并发症、糖尿病等不良反应[3]。对于发生肾功能损伤的患儿应及时调整免疫抑制剂种类或剂量,必要时可考虑使用肾脏保护类药物[15, 77-78]。移植术后高血压的发生多与移植时年龄、免疫抑制剂引起的肾功能损害以及糖皮质激素的使用相关,反复的血压升高应行肾脏功能检查并实施相应治疗[79]。术后新发糖尿病多见于肝移植时年龄>5岁的儿童,且在囊性纤维化、原发性硬化性胆管炎、急性肝坏死等特定疾病中的发生率较高[80-81]。

推荐意见:

46. 移植后肾功能的监测可使用改良的Schwartz公式计算GFR的估计值(2-C);肾功能受损较严重的患儿应在调整免疫抑制方案的同时使用肾脏保护类药物(1-B)。

47. 应注意儿童肝移植术后血压的监测,术后出现高血压的患儿应给予治疗并考虑调整免疫抑制方案(1-B)。

48. 儿童肝移植术后应定期监测空腹血糖,新发糖尿病的诊断与治疗与未接受肝移植的糖尿病患儿相同(1-B)。

3.6.2 生长发育[82-84]

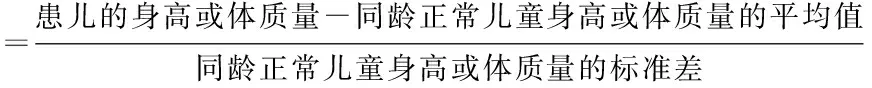

肝病患儿的生长发育常落后于同龄正常儿童,但成功的肝移植手术和术后适当的营养纠正能使大部分患儿实现“追赶生长”。移植后尽量减少糖皮质激素用量或早期撤除糖皮质激素有助于改善患儿的生长发育状态。然而,术后长期的肝功能异常或肾功能损伤则不利于肝移植术后的“追赶生长”。术后身高和/或体质量发育明显滞后、肥胖或骨质疏松的患儿应接受适当的干预治疗。对于身高与体质量的评估,可将其换算为身高或体质量的标准分数(又称Z评分)或同龄正常儿童身高或体质量的百分位数水平。Z评分的计算公式如下:

推荐意见:

49. 儿童肝移植术后应定期监测身高、体质量、体质量指数(BMI)、骨质密度等指标,对于生长发育异常的患儿应查明原因并给予对应的治疗(1-B)。

3.6.3 神经认知发育与社会心理学发育[85-86]

神经认知发育评估内容包括学习、记忆、语言功能、执行能力等。肝移植术前的生长发育情况与术后的CNI药物浓度是影响移植后神经认知发育的主要因素。另外,部分患儿在肝移植后可出现大量缺课、创伤后应激障碍、抑郁、自卑心理等社会心理学问题。评估与纠正儿童肝移植术后的神经认知发育障碍或心理学问题是移植后随访中的重要内容之一。

推荐意见:

50. 对于移植后神经认知发育障碍的患儿应给予必要的康复治疗,并定期评估其恢复情况(1-B);应重视儿童肝移植术后的社会心理学发育,学龄期儿童应积极接受学龄期教育(1-B)。

3.6.4 疫苗接种[66, 87-88]

疫苗接种可有效降低儿童肝移植术后的感染风险。灭活疫苗可在围手术期安全接种,但移植后过早接种疫苗常无法激发足够强度的免疫应答,因此移植后的疫苗接种应在术后2~6个月以后进行。移植后接种减毒活疫苗会引起较大的致病风险,故此类疫苗仅能在移植前为免疫功能正常的患儿接种,且疫苗接种与肝移植的间隔时间应至少达到28 d。另外,积极为患儿的家庭成员接种流感疫苗有助于降低患儿的流感患病率。

推荐意见:

51. 应尽早为患儿接种其年龄适应范围内的常规疫苗(1-B);灭活疫苗可在移植前或移植后2~6个月以后接种(1-B);减毒活疫苗的接种仅限于移植前28 d以上(2-C)。

52. 与患儿有密切接触的家庭成员应每年接种流感疫苗(1-B)。

3.6.5 依从性[8, 89]

肝移植患儿通常需接受终身的免疫抑制剂治疗,稳定的移植物功能有赖于良好的依从性。移植后的不依从在青春期患儿中较为常见,多与服药责任从监护人到患儿本人的过渡有关,其他的危险因素还包括抑郁、经济条件差、特殊的社会状态、创伤后应激障碍等。

推荐意见:

53. 对于反复免疫抑制剂浓度异常的患儿应作依从性评估,必要时增加随访频率或给予其他干预措施(1-B)。

4 总结与展望

虽然大陆地区儿童肝移植的总体疗效与发达国家之间仍存在差距,但是我国的儿童肝移植事业正在兴起,外科技术日趋成熟,活体肝移植已逐渐成为主要的移植类型。另外,近年来国家大力推广的器官捐献政策获得了较明显的成效,极大地缓和了儿童尸体器官短缺状态;多形式儿童肝移植如劈离式肝移植、婴幼儿单段活体肝移植、婴幼儿超减体积活体肝移植、辅助性肝移植、多米诺肝移植等技术的逐步开展也使得越来越多的终末期肝病患儿获得了肝移植的机会。然而,目前全国各个中心在儿童肝移植的操作与管理中尚无统一标准,且相关学科间缺乏交流与合作。本指南的发布将为中国儿童肝移植的临床实践提供理论指导,对提高我国儿童肝移植整体水平、加强多学科合作有着重要意义。我们相信在广大学者与同行的共同努力下,中国的儿童肝移植事业将会有更好的发展。

5 利益声明

本指南的发布不存在与任何公司、机构或个人之间的利益冲突。

执笔:夏强(上海交通大学医学院附属仁济医院)

审稿专家(按姓氏拼音排序):陈其民(上海交通大学医学院附属上海儿童医学中心);冯杰雄(华中科技大学同济医学院附属同济医院);高伟(天津市第一中心医院);贺强(首都医科大学附属北京朝阳医院);李波(四川大学华西医院);李威(武警总医院);石炳毅(解放军第309医院);孙丽莹(首都医科大学附属北京友谊医院);王建设(复旦大学附属金山医院);夏强(上海交通大学医学院附属仁济医院);徐骁(浙江大学医学院附属第一医院);杨家印(四川大学华西医院);张峰(江苏省人民医院);郑树森(浙江大学医学院附属第一医院);朱志军(首都医科大学附属北京友谊医院)

1 United Network for Organ Sharing[DB/OL]. http://www.unos.org/.

2 Kasahara M, Umeshita K, Inomata Y, et al. Long-term outcomes of pediatric living donor liver transplantation in Japan: an analysis of more than 2 200 cases listed in the registry of the Japanese Liver Transplantation Society[J]. Am J Transplant, 2013, 13(7):1830-1839.

3 Kelly DA, Bucuvalas JC, Alonso EM, et al; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; American Society of Transplantation. Long-term medical management of the pediatric patient after liver transplantation: 2013 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation[J]. Liver Transpl. 2013;19(8):798-825.

4 Squires RH, Ng V, Romero R, et al. Evaluation of the pediatric patient for liver transplantation: 2014 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American Society of Transplantation and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition[J]. Hepatology, 2014,60(1):362-398.

5 GRADE working group[DB/OL]. http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/index.htm.

6 中国肝移植注册. 2011年儿童肝移植科学报告[EB/OL]. http://www.cltr.org/.

7 Fagiuoli S, Daina E, D′Antiga L, et al. Monogenic diseases that can be cured by liver transplantation[J]. J Hepatol, 2013,59(3):595-612.

8 Kerkar N. Liver transplantation: a pediatric perspective[M]//Ahmad J, Friedman SL, Dancygier H. Mount Sinai expert guides: Hepatology. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2014:394-403.

9 Ahmed A, Keeffe EB. Current indications and contraindications for liver transplantation[J]. Clin Liver Dis, 2007, 11(2):227-247.

10 Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network[DB/OL]. http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/.

11 Arguedas MR, Abrams GA, Krowka MJ, et al. Prospective evaluation of outcomes and predictors of mortality in patients with hepatopulmonary syndrome undergoing liver transplantation[J]. Hepatology, 2003, 37(1):192-197.

12 Condino AA, Ivy DD, O′Connor JA, et al. Portopulmonary hypertension in pediatric patients[J]. J Pediatr, 2005, 147(1):20-26.

13 Krowka MJ, Swanson KL, Frantz RP, et al. Portopulmonary hypertension: Results from a 10-year screening algorithm[J]. Hepatology, 2006, 44(6):1502-1510.

14 Miller MR, Sokol RJ, Narkewicz MR, et al. Pulmonary function in individuals who underwent liver transplantation: from the US cystic brosis foundation registry[J]. Liver Transpl, 2012, 18(5):585-593.

15 Schwartz GJ, Mu oz A, Schneider MF, et al. New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD[J]. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2009, 20(3):629-637.

16 Finney H, Newman DJ, Thakkar H, et al. Reference ranges for plasma cystatin C and creatinine measurements in premature infants, neonates, and older children[J]. Arch Dis Child, 2000, 82(1):71-75.

17 Samyn M, Cheeseman P, Bevis L, et al. Cystatin C, an easy and reliable marker for assessment of renal dysfunction in children with liver disease and after liver transplantation[J]. Liver Transpl, 2005, 11(3):344-349.

18 Sultan MI, Leon CD, Biank VF. Role of nutrition in pediatric chronic liver disease[J]. Nutr Clin Pract, 2011, 26(4):401-408.

19 Sathe MN, Patel AS. Update in pediatrics: focus on fat-soluble vitamins[J]. Nutr Clin Pract, 2010, 25(4):340-346.

20 Sullivan JS, Sundaram SS, Pan Z, et al. Parenteral nutrition supplementation in biliary atresia patients listed for liver transplantation[J]. Liver Transpl, 2012, 18(1):120-128.

21 Kaller T, Schulz KH, Sander K, et al. Cognitive abilities in children after liver transplantation[J]. Transplantation, 2005, 79(9):1252-1256.

22 Sorensen LG, Neighbors K, Martz K, et al. Cognitive and academic outcomes after pediatric liver transplantation: Functional Outcomes Group (FOG) results[J]. Am J Transpl, 2011, 11(2):303-311.

23 Lykavieris P, Chardot C, Sokhn M, et al. Outcome in adulthood of biliary atresia: a study of 63 patients who survived for over 20 years with their native liver[J]. Hepatology, 2005, 41(2):366-371.

24 Seda Neto J, Feier FH, Bierrenbach AL, et al. Impact of Kasai Portoenterostomy on Liver Transplantation Outcomes: A Retrospective Cohort Study of 347 Children with Biliary Atresia[J]. Liver Transpl, 2015, 21(7):922-927.

25 Sokol RJ, Shepherd RW, Superina R, et al. Screening and outcomes in biliary atresia: summary of a National Institues of Health wordshop[J]. Hepatology, 2007,46(2):566-581.

26 Emerick KM, Rand EB, Goldmuntz E, et al. Features of Alagille syndrome in 92 patients: frequency and relation to prognosis[J]. Hepatology, 1999, 29(3):822-829.

27 Kasahara M, Sakamoto S, Horikawa R, et al. Living donor liver transplantation for pediatric patients with metabolic disorders: the Japanese multicenter registry[J]. Pediatr Transplant, 2014, 18(1):6-15.

28 Mazariegos G, Shneider B, Burton B, et al. Liver transplantation for pediatric metabolic disease[J]. Mol Genet Metab, 2014, 111(4):418-427.

29 Liu E, MacKenzie T, Dobyns EL, et al. Characterization of acute liver failure and development of a continuous risk of death staging system in children[J]. J Hepatol, 2006, 44(1):134-141.

30 Lu BR, Zhang S, Narkewicz MR, et al; Pediatric Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Evaluation of the liver injury unit scoring system to predict survival in a multinational study of pediatric acute liver failure[J]. J Pediatr, 2013, 162(5):1010-1016.

31 Ismail H, Broniszczak D, Kaliciński P, et al. Liver transplantation in children with hepatocellular carcinoma. Do Milan criteria apply to pediatric patients [J]. Pediatr Transplant, 2009, 13(6):682-692.

32 Romano F, Stroppa P, Bravi M, et al. Favorable outcome of primary liver transplantation in children with cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Pediatr Transplant, 2011, 15(6):573-579.

33 Egawa H, Oike F, Buhler L, et al. Impact of recipient age on outcome of ABO-incompatible living-donor liver transplantation[J]. Transplantation, 2004, 77(3):403-411.

34 Okada N, Sanada Y, Hirata Y, et al. The impact of rituximab in ABO-incompatible pediatric living donor liver transplantation: the experience of a single center[J]. Pediatr Transplant, 2015,19(3):279-286.

35 Schukfeh N, Lenz V, Metzelder ML, et al. First case studies of successful ABO-incompatible living-related liver transplantation in infants in Germany[J]. Eur J Pediatr Surg, 2015, 25(1):77-81.

36 Popescu I, Habib N, Dima S, et al. Domino liver transplantation using a graft from a donor with familial hypercholesterolemia: seven-yr follow-up[J]. Clin Transplant, 2009, 23(4):565-570.

37 Liu C, Niu DM, Loong CC, et al. Domino liver graft from a patient with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia[J]. Pediatr Transplant, 2010, 14(3):E30- E33.

38 Popescu I, Dima SO. Domino liver transplantation: how far can we push the paradigm [J]. Liver Transpl, 2012, 18(1):22-28.

39 Rela M, Muiesan P, Andreani P, et al. Auxiliary liver transplantation for metabolic diseases[J]. Transplant Proc, 1997, 29(1-2):444-445.

40 Rosenthal P, Roberts JP, Ascher NL, et al. Auxiliary liver transplant in fulminant failure[J]. Pediatrics, 1997, 100(2):E10.

41 de Goyet JV, Rogiers X, Otte JB. Split-liver transplantation for the pediatric and adult recipient[M]// Busuttil RW, Klintmalm GK. Transplantation of the Liver. New York: Saunders, 2005:609-627.

42 Ackermann O, Branchereau S, Franchi-Abella S, et al. The long-term outcome of hepatic artery thrombosis after liver transplantation in children: role of urgent revascularization[J]. Am J Transplant, 2012, 12(6):1496-1503.

43 Gu L, Fang H, Li F, et al. Impact of hepatic arterial hemodynamics in predicting early hepatic arterial thrombosis in pediatric recipients younger than three yr after living donor liver transplantation[J]. Pediatr Transplant, 2015, 19(3):273-278.

44 Gu LH, Fang H, Li FH, et al. Prediction of early hepatic artery thrombosis by intraoperative color Doppler ultrasound in pediatric segmental liver transplantation[J]. Clin Transplant, 2012, 26(4):571-576.

45 Warnaar N, Polak WG, de Jong KP, et al. Long-term results of urgent revascularization for hepatic artery thrombosis after pediatric liver transplantation[J]. Liver Transpl, 2010, 16(7):847-855.

46 Rodríguez-Castro KI, Porte RJ, Nadal E, et al. Management of nonneoplastic portal vein thrombosis in the setting of liver transplantation: a systematic review[J]. Transplantation, 2012, 94(11):1145-1153.

47 Jensen MK, Campbell KM, Alonso MH, et al. Management and long-term consequences of portal vein thrombosis after liver transplantation in children[J]. Liver Transpl, 2013, 19(3):315-321.

48 Takatsuki M, Chen CL, Chen YS, et al. Systemic thrombolytic therapy for late-onset portal vein thrombosis after living-donor liver transplantation[J]. Transplantation, 2004, 77(7):1014-1018.

49 Sommovilla J, Doyle MM, Vachharajani N, et al. Hepatic venous outflow obstruction in pediatric liver transplantation: technical considerations in prevention, diagnosis, and management[J]. Pediatr Transplant, 2014, 18(5):497-502.

50 Ko GY, Sung KB, Yoon HK, et al. Early posttransplant hepatic venous outflow obstruction: Long-term efficacy of primary stent placement[J]. Liver Transpl, 2008, 14(10):1505-1511.

51 Dechêne A, Kodde C, Kathemann S, et al. Endoscopic treatment of pediatric post-transplant biliary complications is safe and effective[J]. Dig Endosc, 2015, 27(4):505-511.

52 Laurence JM, Sapisochin G, DeAngelis M, et al. Biliary complications in pediatric liver transplantation: incidence and management over a decade[J]. Liver Transpl, 2015, 21(8):1082-1090.

53 Sharma S, Gurakar A, Jabbour N. Biliary strictures following liver transplantation: past, present and preventive strategies[J]. Liver Transpl, 2008, 14(6):759-769.

54 Tanaka H, Fukuda A, Shigeta T, et al. Biliary reconstruction in pediatric live donor liver transplantation: duct-to-duct or Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy[J]. J Pediatr Surg, 2010, 45(8):1668-1675.

55 Humar A, Snydman D; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Cytomegalovirus in solid organ transplant recipients[J]. Am J Transplant, 2009, 9 (Suppl 4):S78-S86.

56 Ljungman P, Griffiths P, Paya C. Definitions of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in transplant recipients[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2002, 34(8):1094-1097.

57 Madan RP, Campbell AL, Shust GF, et al. A hybrid strategy for the prevention of cytomegalovirus-related complications in pediatric liver transplantation recipients[J]. Transplantation, 2009, 87(9):1318-1324.

58 Danziger-Isakov L, Bucavalas J. Current prevention strategies against cytomegalovirus in the studies in pediatric liver transplantation (SPLIT) centers[J]. Am J Transplant, 2014, 14(8):1908-1911.

59 Green M, Michaels MG. Epstein-Barr virus infection and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder[J]. Am J Transplant, 2013, 13(Suppl 3):41-54.

60 Allen UD, Preiksaitis JK; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Epstein-Barr virus and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder in solid organ transplantation[J]. Am J Transplant, 2013, 13(Suppl 4):107-120.

61 Narkewicz MR, Green M, Dunn S, et al; Studies of Pediatric Liver Transplantation Research Group. Decreasing incidence of symptomatic Epstein-Barr virus disease and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder in pediatric liver transplant recipients: report of the studies of pediatric liver transplantation experience[J]. Liver Transpl, 2013, 19(7):730-740.

62 Reshef R, Vardhanabhuti S, Luskin MR, et al. Reduction of immunosuppression as initial therapy for posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder[J]. Am J Transplant, 2011, 11(2):336-347.

63 Xi ZF, Xia Q, Zhang JJ, et al.Denovohepatitis B virus infection from anti-HBc-positive donors in pediatric living donor liver transplantation[J]. J Dig Dis, 2013, 14(8):439-345.

64 Rao W, Xie M, Yang T, et al. Risk factors fordenovohepatitis B infection in pediatric living donor liver transplantation[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2014, 20(36):13159-13166.

65 Jonas MM, Block JM, Haber BA, et al; Hepatitis B Foundation. Treatment of children with chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: patient selection and therapeutic options[J]. Hepatology, 2010, 52(6):2192-2205.

66 Allen U, Green M. Prevention and treatment of infectious complications after solid organ transplantation in children[J]. Pediatr Clin North Am, 2010, 57(2):459-479.

67 Kelly D, Jara P, Rodeck B, et al. Tacrolimus and steroids versus ciclosporin microemulsion, steroids, and azathioprine in children undergoing liver transplantation: randomized European multicentre trial[J]. Lancet, 2004, 364(9439):1054-1061.

68 Ng VL, Fecteau A, Shepherd R, et al; Studies of Pediatric Liver Transplantation Research Group. Outcomes of 5-year survivors of pediatric liver transplantation: report on 461 children from a north americanmulticenter registry[J]. Pediatrics, 2008, 122(6):e1128-e1135.

69 Taylor AL, Gibbs P, Sudhindran S, et al. Monitoring systemic donor lymphocyte macrochimerism to aid the diagnosis of graft-versus-host disease afterliver transplantation[J]. Transplantation, 2004, 77(3):441-446.

70 Xue F, Han L, Chen Y, et al. CYP3A5 genotypes affect tacrolimus pharmacokinetics and infectious complications in Chinese pediatric liver transplant patients[J]. Pediatr Transplant, 2014, 18(2):166-176.

71 Chen YK, Han LZ, Xue F, et al. Personalized tacrolimus dose requirement by CYP3A5 but not ABCB1 or ACE genotyping in both recipient and donor after pediatric liver transplantation[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(10):e109464.

72 Kelly D. Safety and efficacy of tacrolimus in pediatric liver recipients[J]. Pediatr Transplant, 2011, 15(1):19-24.

73 Gras JM, Gerkens S, Beguin C, et al. Steroid-free, tacrolimus-basiliximab immunosuppression in pediatric liver transplantation: clinical and pharmacoeconomic study in 50 children[J]. Liver Transpl, 2008, 14(4):469-477.

74 Turner AP, Knechtle SJ. Induction immunosuppression in liver transplantation: a review[J]. Transpl Int, 2013, 26(7):673-683.

75 Feng S, Ekong UD, Lobritto SJ, et al. Complete immunosuppression withdrawal and subsequent allograft function among pediatric recipients of parental living donor liver transplants[J]. JAMA, 2012, 307(3):283-293.

76 Koshiba T, Li Y, Takemura M, et al. Clinical, immunological, and pathological aspects of operational tolerance after pediatric living-donor liver transplantation[J]. Transpl Immunol, 2007, 17(2):94-97.

77 Campbell K, Ng V, Martin S, et al; SPLIT Renal Function Working Group. Glomerular filtration rate following pediatric liver transplantation--the SPLIT experience[J]. Am J Transplant, 2010, 10(12):2673-2682.

78 Arora-Gupta N, Davies P, McKiernan P, Kelly DA. The effect of long-term calcineurin inhibitor therapy on renal function in children after liver transplantation[J]. Pediatr Transplant, 2004, 8(2):145-150.

79 McLin VA, Anand R, Daniels SR, et al; for SPLIT Research Group. Blood pressure elevation in long-term survivors of pediatric liver transplantation[J]. Am J Transplant, 2012, 12(1):183-190.

80 Hathout E, Alonso E, Anand R, et al; SPLIT study group. Posttransplant diabetes mellitus in pediatric liver transplantation[J]. Pediatr Transplant, 2009, 13(5):599-605.

81 Kuo HT, Lau C, Sampaio MS, et al. Pretransplant risk factors for new-onset diabetes mellitus after transplant in pediatric liver transplant recipients[J]. Liver Transpl, 2010, 16(11):1249-1256.

82 McDiarmid SV, Gornbein JA, DeSilva PJ, et al. Factors affecting growth after pediatric liver transplantation[J]. Transplantation, 1999, 67(3):404-411.

83 Alonso EM, Shepherd R, Martz KL, et al; SPLIT Research Group. Linear growth patterns in prepubertal children following liver transplantation[J]. Am J Transplant, 2009, 9(6):1389-1397.

84 Bartosh SM, Thomas SE, Sutton MM, et al. Linear growth after pediatric liver transplantation[J]. J Pediatr, 1999, 135(5):624-631.

85 Gilmour S, Adkins R, Liddell GA, et al. Assessment of psychoeducational outcomes after pediatric liver transplant[J]. Am J Transplant, 2009, 9(2):294-300.

86 Mintzer LL, Stuber ML, Seacord D, et al. Traumatic stress symptoms in adolescent organ transplant recipients[J]. Pediatrics, 2005, 115(6):1640-1644.

87 Danzinger-Isakov L, Kumar D; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Guidelines for vaccination of solid organ transplant candidates and recipients[J]. Am J Transplant, 2009, 9(Suppl 4):S258-S262.

88 Rubin LG, Levin MJ, Ljungman P, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2014, 58(3):309-318.

89 De Bleser L, Dobbels F, Berben L, et al. The spectrum of non-adherence with medication in heart, liver, and lung transplant patients assessed in various ways[J]. Transpl Int, 2011, 24(9):882-891.

(本文编辑:杨扬)

中华医学会器官移植学分会,中国医师协会器官移植医师分会. 中国儿童肝移植临床诊疗指南(2015版)[J/CD]. 中华移植杂志:电子版, 2016, 10(1):2-11.

10.3877/cma.j.issn.1674-3903.2016.01.002

夏强,200127 上海交通大学医学院附属仁济医院肝脏外科(Email:xiaqiang@medmail.com.cn);石炳毅,100091 北京, 解放军第309医院器官移植研究所(Email:shibingyi@medmail.com.cn)

2016-01-20)