AFRICA IN GUANGZHOU

By Christopher Cottrell

A decade in Chinas largest African quarter

高速發展的中国经济吸引了许多外籍人士前来中国旅行、定居,广州的“小非洲”就是这种现象的一个缩影。

过去十年,他们经历了什么?

Inside the windy cavern of the hotel lobby, fans hummed above the already ice-cold air conditioning. Flies buzzed and the smell of smoked fish wafted across the lobby from the first floor halal restaurant. The mall was defined by chrome pillars with pale grease smears, and plastic door flaps. Further inside, a warren of glass-walled shops brimmed with garbage bags full of sports jerseys, combat boots, womens knit caps, and electronics—from rice cookers to blenders and mobile phones.

The casual observer first takes note of the hair shop. Rather than offering haircuts, it sold hair extensions. Trash bags of straight ebony hair were strewn across the ground and two African women were combing through them for the finest specimens.

One woman, Clarisse from Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, told me that she came twice a year to Guangzhou to buy the hair—all from Chinese scalps. This little detail was great grist for the media mill in 2008, but more importantly it heralded a far more significant trend. Today, the Sino-African hair trade is valued at some 88 million USD per annum. It supports the entire city of Taihe in Anhui Province with huge Chinese hair factories making weaves from black locks all over China and Southeast Asia.

Its a mere extension of the billions of dollars being exchanged between China and Africa—with the World Bank estimating it to be 170 billion USD for 2013, and the Chinese Ministry of Finance and Commerce (MOFCOM) putting it at 300 billion USD for 2015.

Since Chinese president Xi Jinping took the helm, trade with Africa has nearly doubled. This will have long reaching and peculiar ramifications, especially in Guangzhou.

Heralded as the City of Five Rams, Guangzhous African community is arguably the largest in Asia—with Guangzhou government figures claiming the resident population to be 15,000 and 20,000 with long-term resident numbers over 5,000, according comments from the citys executive vice mayor Chen Rugui in December 2015.

Chen said that Guangzhou records more than two million arrivals and departures by foreign nationals each year at its checkpoints, of which about ten percent, or 200,000 arrivals and departures, are from Africa.

Many of those 200,000 make their living in Foshan and Dongguan. Other cities like Beijing and Yiwu in Zhejiang Province, host notable populations of Africans, but they do not have entire enclaves.

African communities in China are nothing new, and in the late 1980s became the focal point of mass demonstrations by enraged students, both Chinese and African. Mao Zedongs concept of “third world solidarity” had brought many African students to China, and many Chinese students seethed with anger when they saw African men with Chinese women, resulting in protests by both sides of a very sensitive cultural divide.

In 2014, over 430,000 Africans came into China, most for quick buying trips. How many stayed on is unknown, but Guangzhou is clearly the capital for Africans in China and its ranks are growing.

However, “Little Africa” is perhaps a misnomer for the area. Some local media in 2005 first dubbed the area “Little Cairo” as it was as populated by Arab, Persian, Turk, Indian, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi ethnicities, as much as it was by Africans and various Chinese minorities such as Uyghur and Hui. But people from the Middle East, Turkey, and South Asia can be found living all over the city—this holds less so for the African population. Despite the varied nations, cultures, identities, and religions, this area became an enclave of African culture unto itself.

Given Guangzhous chaotic downtown area of Yuexiu (越秀) in the belly of the first inner-ring road, one used to rely on two of the three then existing world-class hotels in the city for geographical reference—the Garden Hotel and the Marriott China Hotel. In the buffer zones between these two hotels, stretching along HuanshiDonglu Road and HuanshiZhonglu Road and intersecting at the north-south running Xiaobei Lu Road (小北路) is the main artery of this pulsing slice of Africa and the Middle East in China. Standing as its trade epicenter and de-facto cultural embassy is the Tianxiu Building (天秀大廈). It is nicknamed Guangzhous “Chongqing Mansions” after the shopping and guest-house tower of Africans, South Asians, and Middle Easterners in Kowloon, Hong Kong.

From the lobby and throughout the above apartment tower, Tianxiu was a honeycomb lattice of all kinds of shops. Between 2005 and 2009, French-speaking African women congregated in a private living room that served as a Senegalese restaurant. The hallway outside the apartment was packed with Africans eating plates of fufu rice and barbecued chicken. Cigarette smoke mixed with the cooking chicken provided a heady sensation as Senagalese pop-music blared off the concrete walls. It closed in 2010 as Guangzhou began cleaning up for the 2010 Asia Games.

This area around Xiaobei Lu began seeing thousands of Africans visit in the 1990s as China deepened economic reforms and Guangdong emerged as the nations manufacturing capital. Finding industrial and manufacturing troubles in their own countries, these newcomers arrived in droves at the annual April and October Canton Fairs—cramming shipping containers full of whatever they could.

Just east of the Guangzhou West Train Station, the neighborhoods bound by HuanshiDonglu to the south and Luhu Park to the north, teemed with Hui Muslim Chinese and Uyghurs. Many of them profited for halal restaurants and tea-houses from the influx of traders coming in with Islamic preferences. A community grew, but it was bound culturally and economically from the rest of the international community in the city.

One seldom encountered Africans during the day outside of this area or another commercial area in northwestern Guangzhou, Sanyuan Li, until 2012.

At night, many Africans felt safe to wander past what is now the Crowne Plaza Hotel on HuanshiDonglu Road to three bars—the Old Elephant and Castle, the Gypsy King, and Cave Bar. This is where many would come to party all night. After all, a few blocks northeast from Xiaobei Lu, are forests of apartments tightly knit with tiny alleys inhabited by Chinese Muslims and Muslims from other countries. So, no noisy bars and only a few restaurants even offering beer. The Gypsy King was, and is, a notorious African hangout bar. The evenings dancing snake girl is of particular popularity. At the corner of Jianshe Lu Road at the Garden Hotel, Africans used to get a bad rap—as several drug dealers, allegedly from Nigeria, used to line the street and accost expats and foreign tourists for hashish and harder drugs.

This, perhaps, highlighted divisions within the African community here. One businesswoman from Togo claimed in 2006, “Be careful of the Nigerians. They are the ones making trouble here.”

Han Chinese, of course, have varying levels of multicultural understanding and police are often suspicious of the outsiders. In 2006, just as China and many African nations were formalizing further trade relations at the third Beijing Summit Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), a Chinese police officer explained to me that they were worried about African crimes.

“We are seeing more drug-dealing related crime with Africans. You foreigners should be careful if you break the law in China. We have a special prison to process and deport you here in Guangzhou…There are many Africans in it,” she said.

She claimed that, “When we police go into the African area we are very nervous as many run from us…One time we went into a room and there was an African man there with pictures of his four wives. He pulled a knife on us and jumped out the window onto the next balcony and escaped.”

In the climate of uncertainty and suspicion, things can quickly spiral out of control. In 2009, an African male jumped out of a building on Xiaobei Lu and died while evading police. Scores of African residents later protested by marching on the local police station—an unheard of event in China by any foreign community. The police told media that they were trying to check the mans passport as part of regular visa checks.

This was often a recurring theme—hostility emerged toward police patrols, particularly when they occurred within the context of searches on Africans suspected of drug dealing along Jianshe Lu Road. There were several high-profile cases between 2006 and 2008 in which Africans were found smuggling and selling drugs. Among them eight African drug smugglers were convicted and sentenced to death with a two-year reprieve in November 2008. In December 2012, Guangzhou police cracked down on a drug dealing group formed of over 300 Africans.

Arrests such as these contribute to the climate of mistrust that a lot of Chinese feel toward their African neighbors.

One fascinating way of viewing the cross-cultural relations in the area came via a 2012 report in the Global Times, which looked at the relatively rare instances of marriage among African immigrants and Chinese.

Jo Gan, an African American woman married to a Chinese man, said that Black-Asian couples were rare, and part of the problem was “media stereotypes that portray black women as difficult to control, oversexed, larger, and not attractive due to skin-color and body shape.”

The article further cited Chinese cultural preferences for whiter skin—as evidenced by womens facial products and even the “facekinis” worn bydama at Chinese beaches to prevent tanning. The hostility can, on occasion, be a two-way street.

“They are racist devils, I tell you Christopher,” said a man named Jeremiah from Kenya one night around 5 am in the summer of 2013.

“I came to make big money. But my investor stopped sending me cash. Now I am stuck here. I have some business but I am just saving up for my ticket home. It is so expensive and my visa has expired. I want to tell this to everyone in Africa,” he said.

Two weeks later, another African lashed out in frustration. At around 3:30 am in a hotel lobby near BaohanZhijie Street—an intensely populated lane cutting through Little Africas deepest heart—dozens of Chinese were eating outside when an altercation erupted with a young African man. He kicked over a table and bottles flew everywhere. Giving chase, young Chinese men threw bottles at him and the glass exploded near observers passing by, who then ducked into a hotel lobby and watched as the African kicked over an empty security guard pillbox. He seized its umbrella and held it like a spear as he charged the Chinese. They pulled back and he ran off down an obscure alley.

It would be easy to get the impression that the community is brimming with constant conflict, but it is important to keep in mind the economic and social factors that drew migrants to the area in the first place.

As an example, Mwamba, 34, monitors commodity prices and helps his boss in Dubai decide on import orders for Chinese goods. He told Xinhua that since moving to Guangzhou he has gained experience in selling electrical gadgets, accessories, furniture, and motorbikes and now has knowledge of international freight logistics. “I always tell my friends from Africa that we are lucky to settle here.”

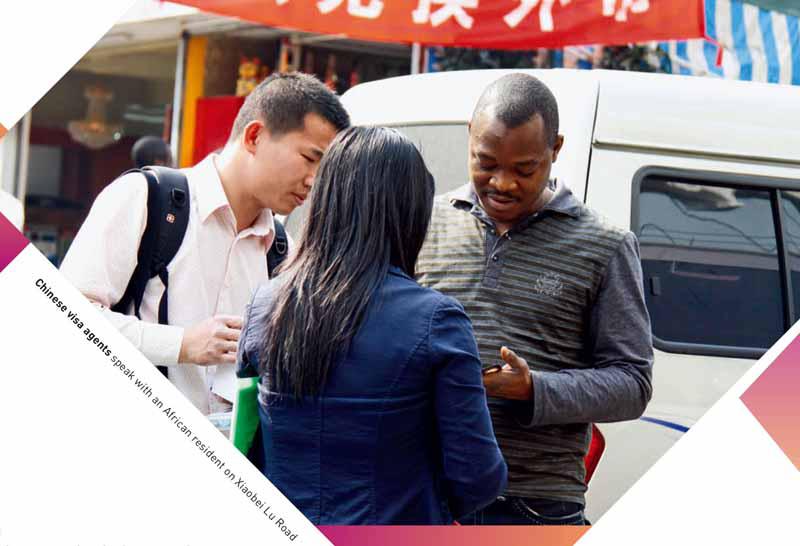

He also found a Chinese girlfriend and they will purchase an apartment together before getting married.Meanwhile, the various chambers of commerce of different African nations in Guangzhou also play an important role in resolving tensions. In Guangzhou there are over ten African organizations that bridge the gap between the African residents and locals. Kubi, 39, from Ghana is the secretary-general in Ghana Chamber of Commerce in Guangzhou. He told the NanduDaily that nearly every Ghanaian knows him and that they go to him directly for answers to visa and rent problems.

For all the tales of conflict that occupy the headlines, the day to day life within Guangzhous Little Africa is far more prosaic—people lured by the promise of a better life, sometimes finding what they seek, sometimes not. This reality can be encompassed in the sights and smells of BaohanZhijie Street, what was once an urban bazaar teeming with Africans in traditional dress and Arabs in keffiyah headdresses. Women—African, Middle Eastern, Chinese—don full burqahs. Before its major clean-up in 2014 and 2015, fruit and vegetable sellers lined Baohan with plastic sheets of goods. Heavy smoke from barbecued fish and lamb sellers wafted like clouds through the dangling string roots of hundred-year-old banyan trees. Hundreds of shops in the surrounding alleys sold ceramic toilets, lacquered doors, Haj pilgrimage garb, ceiling lights, and glass windows. Phone booths with direct call services to Africa were interspersed with foot massage and nail parlors catering specifically to African women.

It has been cleaned up with the times, but those seeking these things can still find them if they look hard enough through the multicultural heart of the area that still beats within.