Sowing for a Second Boom

by+Zi+Mo

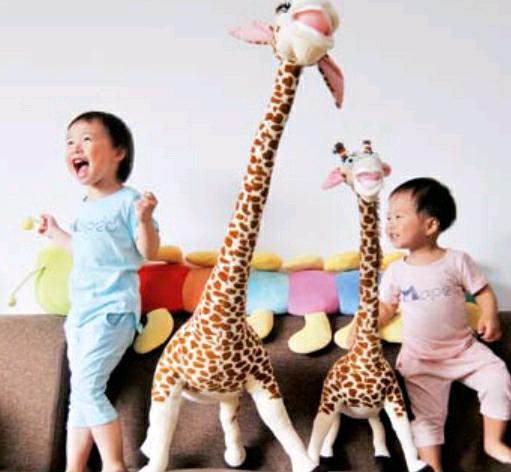

A change in the national policy allowing couples to have a second child – passed at the Fifth Plenary Session of 18th CPC Central Committee held in October 2015 – ends the 30-year-old one-child policy and heralds a second-child boom in China.

The one-child policy dates back to the late 1970s, when Chinas economy went through a chaotic stage after the “cultural revolution” (1966-1976), with 250 million people stuck in poverty. In 1978, Chinas GDP ranked 15th in the world, and its per capita GDP ranked second from the bottom – one result of a heavy population restraining the economic development.

The Chinese government thus laid down the “one couple, one child” policy to ease the pressure on resources arising from rapid population growth. “The idea of controlling population quantity and upgrading its quality was initiated at the Fourth Plenary Session of the Fifth National Peoples Congress (NPC) in 1981,”recalls Peng Peiyun, former head of the State Family Planning Commission.

In the 30-plus years since then, great changes have taken place in the countrys economy and population structure, helped further by the reform and opening up. Aging has emerged as a challenge just when China has become the worlds second largest economy trailing the United States.

Statistics indicate that Chinas population under 14 years accounted for 33.6 percent of the total in 1982 and dropped to 16.5 percent in 2014 – 27 percent lower than the world average and 20 percent lower than that of the U.S. At the same time, those above 65 years were 137 million in 2014, making up 10.1 percent of the total population.

“The rate of aging is irreversible,” insists Lu Mai, secretary general of the China Development Research Foundation. One of the reasons behind Chinas aging is a fall in youth population caused by the one-child policy. The proportion of those above 65 is expected to exceed 15 percent and 20 percent by 2027 and 2035, respectively; and, 25 percent by 2050. If not adjusted, according to a United Nations report, Chinas dependency ratio will rise contin- uously after the mid-21st Century touching as high as 0.8 by 2070, which means four laborers have to provide for at least two elders and one child. That would push China to the brink of economic decline with the erosion of the demographic dividend that enabled economic development over the last three decades.

The year-by-year fall in the working-age population and the rising pressure on social provision for the aged triggered loud calls from across the country – including from decision makers, academic circles, and the general public – for abolition of the one-child policy. At the eleventh hour, the government seized the opportunity for correcting the population structure by launching the second-child policy. In 2013, there was a conditional relaxation: any of a couple who was an only child in his/her family was allowed to have another child. According to official figures, by the end of September 2015, 1.76 million eligible couples had applied for a second child.

“Its not only about protecting the equal fertility right of the non-only-child community, but also a way to minimize the crisis of falling young population,” remarks Prof. Mu Guangzong from Peking Universitys Population Research Institute. “The move is essential for a moderate birth rate and sustainable development of a population balance.”

Analysts believe that at present, there are 90 million couples eligible for a second child. The anticipated second-child boom over the next few years will consume 100 billion yuan annually, replenish a long-term labor supply, and restore the population structure.

Wang Peian, deputy director of the National Health and Family Planning Commission, believes that the policy will result in abundant labor resource and light dependency burden – thus presenting a favorable opportunity to adjust and improve the family planning policy. “The implementation of the second-child policy will drive consumption in such segments as women and child health, baby and infant goods, nursery and kindergarten services, and education,” noted Deputy Director Wang. “In the long run, by 2050, the working-age population between 15 and 59 will increase by 30 million, beneficial to stabilizing our economic growth.”

“Different people have different understandings about the second-child policy,” opines Li Shuzhuo, head of the Population and Development Research Institute under Xian Jiaotong University. “To me, it is encouraging. One of the objectives for such an adjustment is to encourage people to have more children so as to properly raise fertility for dealing with the tension in Chinas internal structure and distribution of population, aging, labor shortage, and inputs for economic growth.”

The policy is only a permit for birth. The question is whether couples want or can afford a second child. The increasing cost of child-raising and the growing pressure on providing for the aged have led to changes in peoples thinking, especially in urban China. A low-birth-rate culture has taken shape over the last few years, which might slow down the implementation of the secondchild policy.

The new policy might not fall in place as expected without more supportive measures, such as expanding education, lowering the cost of parenting, and providing for the aged. “The next step of the policy should be a transition to encourage births with incentive measures,” asserts Li Shuzhuo. “This is also a new subject for scholars and specialists to deal with. To encourage new policy might require steps such as tax reduction and paid leave. There should be more policy-oriented research with regards to the allocation of social and medical resources to meet the demands of older womens pregnancy and reproductive health. The existing system, which has served the previous policy, should be fixed.”

As China turns the page of the only-child generation and prepares for a second-child boom, the government should offer a“policy bonus” for more people to say “yes.”