现代性更难

∷林巍 文/译

原 文

[1] 周围的同胞们去国外旅游,回来后常听他们讲,美国、欧洲的那些城市也没什么,马路、建筑还不如我们的好呢,或曰还不如我们现代化。我想,那大概是因为他们大都“下车拍照、上车睡觉”,看到更多的是“现代化”而非“现代性”。

[2] 分析起来,“现代”的含义,主要包括两个方面,即现代化和现代性。现代化,主要是从经济和社会层面上来谈论问题,如社会从农业文明进入工业文明过程中所体现的生产方式转型、经济增长、社会发展、教育普及、知识提高等方面的根本变化;而现代性,则主要在哲学层面、从理性高度审视真正现代化社会的含义,从思想观念与行为方式上把握现代化社会的属性、意识和精神。简言之,前者侧重于生产和物质,后者侧重于制度和精神;所以,二者是不同性质的概念。一个社会,可能具有了某种程度的现代化,但不一定必然具有现代性。

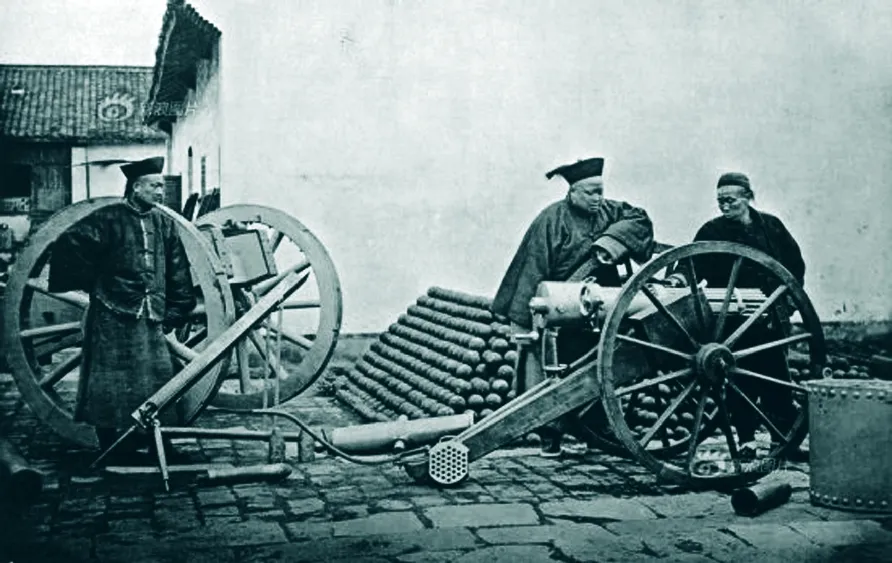

[3] 现代化不易,现代性则更难。以此观点回顾中国近代史,自19世纪60年代以来,主要经历了三次重大社会变革:第一次是洋务运动,约30年,以甲午战争和《马关条约》为标志而失败;第二次是戊戌变法,到20世纪20年代,约30年,亦未成功;第三次便是上世纪80年代初开始的改革开放,至今30余年,在经济层面上可谓成功。然而,这三次有一共同特点,即都以现代化压过了现代性。

[4] 现代性的基本特征是法治社会和公民意识。传统社会的统治,靠的是神圣信仰、礼俗、特权、身份、宗法、血缘等,中国传统社会的“君君、臣臣、父父、子子”便最为典型;而现代社会是靠理性设计出来的法律来维持统治,其基本特征是法制化,废除特权,强调人的独立性、平等性、自觉性和能动性。

[5] 既然现代性是一种社会理念和精神财富,就须通过一定社会模式和制度安排得以实现和彰显。现代性不是自发形成的,而是一种自觉的社会功能;在制度与人性的互动中,不断测试、概括、整合和提升,进而渗透在人们的日常生活方式中。

[6] 严格讲,现代性不是看出来的,而是体悟出来的;要在那里切切实实地生活、经历一段,才会感到人性在不同制度框架下所进化的文明程度。

译 文

[1] Quite often, I hear my countrymen speak lightly about the roads or buildings in the United States or Europe after their overseas trips; it seems that ours are much more modern.I reckon they were probably on a tour of “taking photos off the bus while flipping through others” and they have been so obsessed with “modernization” rather than “modernity”.

[2] By definition, the so-called “modern” consists of two aspects—modernization and modernity. Modernization is generally viewed in China from economic and social aspects,such as fundamental alters of production modes, economic growth, social development, the spread of education and knowledge during the transition from an agrarian society to an industrial one. Modernity, on the other hand, typically refers to rational evaluation of the nature, ideas, spirit and behavioral patterns of fully modernized societies at a philosophical level. Surely, the two are different concepts in different phases of the developmental process, with the former accentuating production and materials and the later stressing the system and spirit. A society may have achieved a certain degree of modernization, but may not be completely modern.

[3] It is not easy to achieve modernization, and even more so modernity. Reviewing modern Chinese history from this point of view, there have been three major modernizing social reforms: the Westernization Movement, which lasted about 30 years, failed miserably with the Sino-Japanese War of 1894—1895 (launched by Japanese imperialists to annex Korea and invade China)and the Treaty of Shimonoseki; a capitalist enlightenment from the Hundred Days Reform (1898) to the 1920s,also about 30 years, ended unsuccessfully; and the most recent “reform and openness” initiated by Deng Xiaoping from the 1980s up to now, has over the past 30 years or so been successful economically. These reforms,nevertheless, have one thing in common: “modernity”was overwhelmed by “modernization”.

[4] Modernity is chiefly characterized by rule of law and civic awareness. Unlike traditional societies which were ruled by holy beliefs, etiquette, custom, and patriarchal kinship typified by the Chinese hierarchical structure of family and social relations, modern societies are governed by laws and regulations designed out of rationality. The core values of a modern society are therefore legislation, equal rights,inde pendence, equality, consciousness and motivation of individuals.

[5] As an idea and spiritual treasure, modernity did not happen spontaneously but consciously in a functional social setting; it is through interactions between systems and humanity that modernity evolves, synchronizes and crystallizes, gradually merging into people’s daily life.

[6] Strictly speaking, modernity is not visibly sensed but has to be felt, experienced and reasoned. Different aspects of human nature, as well as its civilization, may be better revealed and compared when framed in certain environments.

译 注

在[1]中,“下车拍照、上车睡觉”不一定译得那么“实”,而是译出其核心含义,即将旅游过程简化为只重拍照而忽略其他。

在[2]中,将“现代”具体划分:“分析起来,‘现代’的含义,主要包括两个方面,即现代化和现代性”,此处的“分析”未必是by analysis,而是就其性质、定义而言的,故以 by definition 更宜;“而现代性,则主要在哲学层面、从理性高度审视真正现代化社会的含义”,其中的“哲学层面”、“理性高度”在译文中不一定仍然并列,而可分开处理,即由rational evaluation of 和 at a philosophical level构成;“真正现代化社会”亦非为real modernized society,而可从内涵上理解为fully modernized societies;“简言之,前者侧重于生产和物质,后者侧重于制度和精神”,“简言之”未用通常的 in short, concisely, in sum, in conclusion 等,而是surely,以示强调;而对于“前者”、“后者”的处理,则不妨稍加扩展,添入补充成分the two are different concepts in different phases of the developmental process, with the former... and the later...;至于最后一句“一个社会,可能具有了某种程度的现代化,但不一定必然具有现代性”,则又涉及到在更深层次上理解“现代性”的问题,然而此处并未用modernity,而是...completely modern,意为certain degree of modernity,足见可变通的尺度。

然而,对于诸如modernity一类含义丰富而模糊的词汇及其相关篇章的翻译,有时要采取整体贯通的策略,以求得实效。对此,翻译家严复早有论述:“此在译者将全文神理,融会于心,则下笔抒词,自然互备。至原文词理本深,难于共喻,则当前后引衬,以显其意。凡此经营,皆以为达,为达即所以为信也。”(俞政,2003:32)这里的主旨是“全文神理,融会于心”(have a thorough understanding and digested original text in mind beforehand)。

在[6]中,“感到人性在不同制度框架下所进化的文明程度”,其中的“感到”含义颇丰,不是一个简单的feel所能了结,而是一种在比较中的自觉意识,故用了reveal and compare两个动词,且用了被动语态,而“在……制度框架下”则简化为framed in...environments。

在学术界,有学者认为,中国直至近现代,只有“思想”而没有“哲学”(王国维,1905),只有语言文学而没有文法(马建忠,1894),中国的翻译长久以来也只有“文论”而没有“理论”,因而与西方的现代翻译学不在一个层面上。其实,通过上文围绕“现代化”和“现代性”的理解与翻译,就具体翻译中所采用的“变通”策略而言,中西方对此的分析和探索,有着许多交叉、重叠和相通之处。