碎屑电气石的LA-MC-ICPMS硼同位素原位微区分析及其源区示踪: 以哀牢山构造带为例

聂小松, 夏小平, 张 乐, 任钟元, 李 玲

(1. 中国科学院 广州地球化学研究所 同位素地球化学国家重点实验室, 广东 广州 510640; 2. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049)

0 引 言

硼有两个稳定同位素10B和11B, 是自然界中同位素相对质量差最大的元素之一(Δm/m≈10%), 在自然过程中同位素分馏效应十分显著。目前文献报道的自然界中不同储库的δ11B值变化范围为–37‰ ~+58‰[1–4], 其中较负的δ11B值常见于非海相蒸发硼酸盐矿物和某些电气石, 而较正的δ11B值则常见于某些盐湖卤水和蒸发海水[4–5]。硼同位素已广泛应用于地热与水环境地球化学[6–9]、壳-幔演化作用[10–12]、矿床成矿环境及物质来源[13–18]、海陆相形成环境[19–21]、重建古海洋环境与古气候演变[22–25]以及天体地球化学[1,24]研究之中。

目前最广泛使用的硼同位素分析方法为表面热电离质谱(TIMS)法, 该方法具有较高的分析精度但化学分离提纯过程繁琐, 而且该过程可能产生硼同位素分馏[26–27]。近些年硼同位素微区原位分析方法取得了很大的发展, 用离子探针或激光剥蚀多接收电感耦合等离子体质谱(LA-MC-ICPMS)直接对地质样品进行原位硼同位素比值测定可以取得很好的分析结果[28–32]。原位微区分析方法不仅避免了常规热电离质谱法繁杂的化学分离纯化流程, 提高了工作效率, 而且可以对矿物的环带和微层等进行原位分析, 揭示矿物形成的多期次精细过程和不同的形成条件[31–32]。

电气石是常见的副矿物之一, 可以在近地表到上地幔的温压范围内保持稳定, 它硬度大, 物理化学性质非常稳定, 能在岩石风化、沉积物搬运、成岩过程中保持稳定, 是沉积岩中常见的重矿物之一,与锆石、金红石合称为沉积岩中的三大“超稳定的矿物”。这种优良的物理化学稳定性使得碎屑电气石能够准确地指示源区组成, 有效地保留原岩信息[33–35],是物源分析的理想指针矿物[36–37]。岩浆成因和变质成因的电气石具有不同的 Mg、Ca、Fe、Al[34–35]和F、Li[34]组成。这一特征已广泛应用于沉积岩物源研究之中[37–39]。电气石是自然界中硼的主要载体之一,硼含量高(~3%), 因此也是一个硼同位素分析和示踪的理想矿物。

电气石的硼同位素在矿床成因和成岩物质来源[13,15,33,40,41]等方面的研究显示它能很好地保存其形成时的地球化学和同位素信息, 对其寄主岩组成具有良好指示作用[33–35]。结合电气石稳定的物理化学性质, 电气石的硼同位素可以用来对沉积岩进行源区分析, 对沉积岩的源区分析提供新的工具。因此本文利用中国科学院广州地球化学研究所同位素地球化学国家重点实验室建立的LA-MC-ICPMS电气石硼同位素原位微区分析方法, 以哀牢山构造带缝合线两侧碎屑岩为例, 对两侧志留系-泥盆系沉积岩中的碎屑电气石进行原位硼同位素测定, 结合已有的碎屑锆石年代学数据, 尝试反演其物源信息, 为哀牢山构造带的古特提斯演化提供新的制约,探讨碎屑电气石的硼同位素对碎屑岩源区示踪的意义。

1 区域地质背景及样品描述

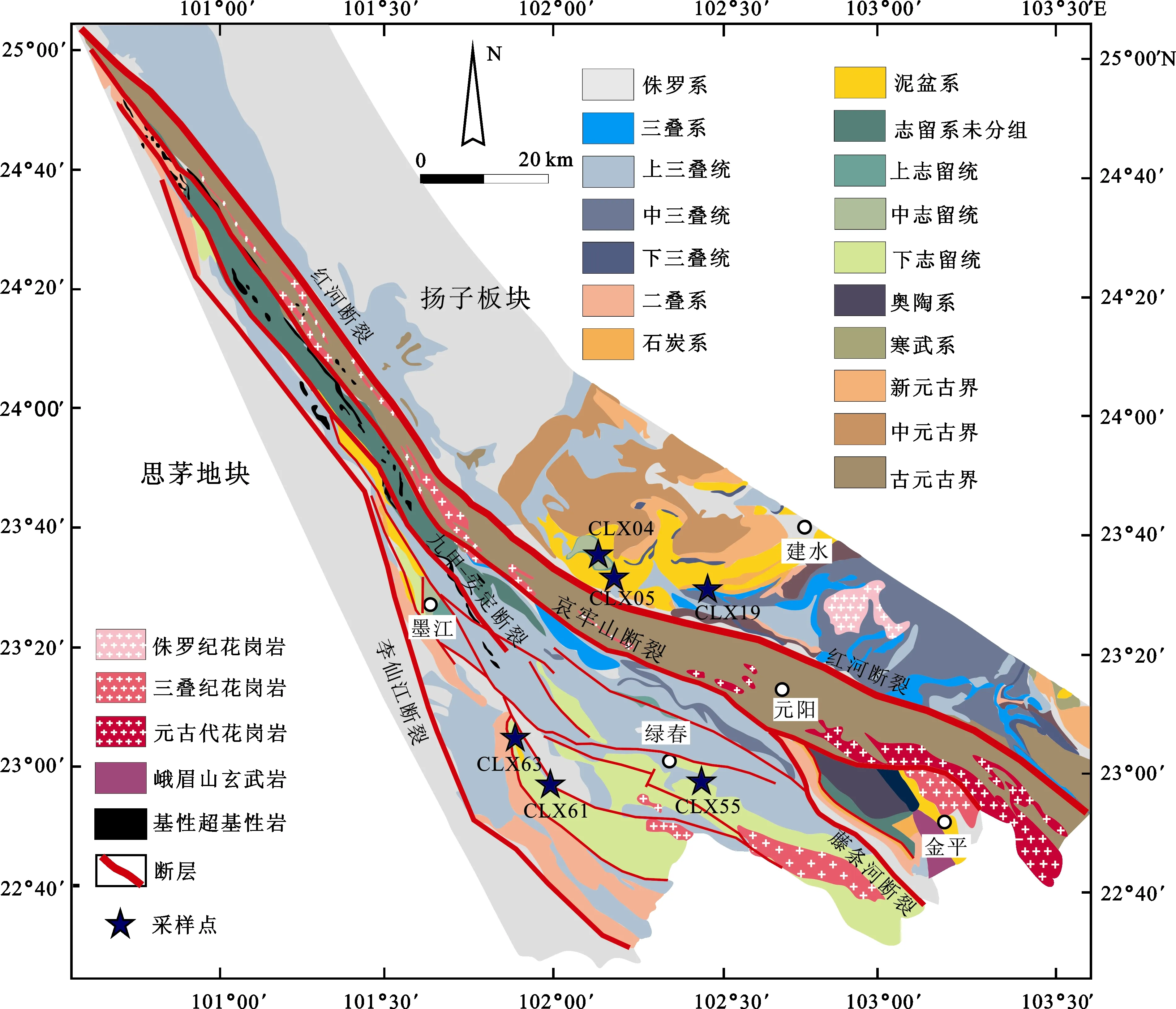

哀牢山构造带夹持于思茅-印支地块与扬子陆块之间[42–43], 经历了哀牢山古特提斯洋或者弧后盆地的打开与闭合, 是理解古特提斯演化最关键的地区之一。该构造带总体呈北西-南东向展布, 北西窄,南东宽, 在云南省中西部延伸上千千米[42,44–47]。哀牢山构造带是一个由不同时代地质单元组合构成的复合构造带, 其组成多样、结构复杂, 经历了长时期、多期次的地块拼贴和改造。该构造带可沿哀牢山断裂分为东西两个部分, 西部主要为奥陶系-早三叠沉积地层, 而东部为元古代哀牢山深变质岩系,而整个区域都发育有大量不同时期的火山-沉积岩、基性-超基性和中-酸性岩(图1)[43]。

哀牢山构造带邻区主要地质单元和断裂边界可依次自西向东划分为: 兰坪-思茅盆地、李仙江-阿墨江断裂、哀牢山构造带、红河断裂、扬子板块(图1)。扬子板块具有太古代-古元古代的结晶基底, 靠近哀牢山构造带的扬子板块西缘结晶基底仅在大红山、东川等地方出露, 大部分区域被新元古代火山-沉积岩、未变质-弱变质古生代地层和二叠纪峨眉山溢流玄武岩所覆盖[43,48]。

图1 哀牢山构造带及邻区区域地质简图Fig.1 Simplified geological map of the Ailaoshan belt and its adjacent region据1990年云南区域地质图[48]及Wang et al.[49]改编

此次的研究地区位于绿春墨江地区和相邻扬子西缘的建水地区。绿春-墨江地区志留系-泥盆系地层出露较完整, 岩性上主要为中细粒砂岩及粉砂岩夹少量页岩(图1, 图2); 建水地区志留系-泥盆系主要为一套中细粒砂岩及粉砂岩夹少量页岩(图1, 图2)。在绿春-墨江地区和建水地区分别采集了样品CLX55、CLX61、CLX63和 CLX04、CLX05、CLX19,所有样品均为中细粒砂岩, 其具体采样层位及位置见图1和图2。

2 实验方法

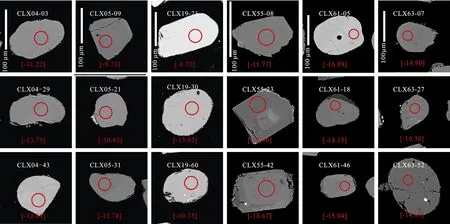

野外采集的新鲜岩石样品送河北廊坊区调研究所实验室通过机械破碎, 淘洗、 磁选和重液分选后,每个样品分离出约1000粒碎屑电气石。然后在双目镜下每个样品随机挑选 200粒, 固定在玻璃板上,以环氧树脂充填固结制成靶, 将其进行抛光。随后将样品靶进行透/反射光以及BSE照相, 获得其内部结构, 以便分析测试时避开破裂或含有包裹体的位置, 并区分可能不同期次形成的环带结构, 筛选出最佳的分析点位(图3)。

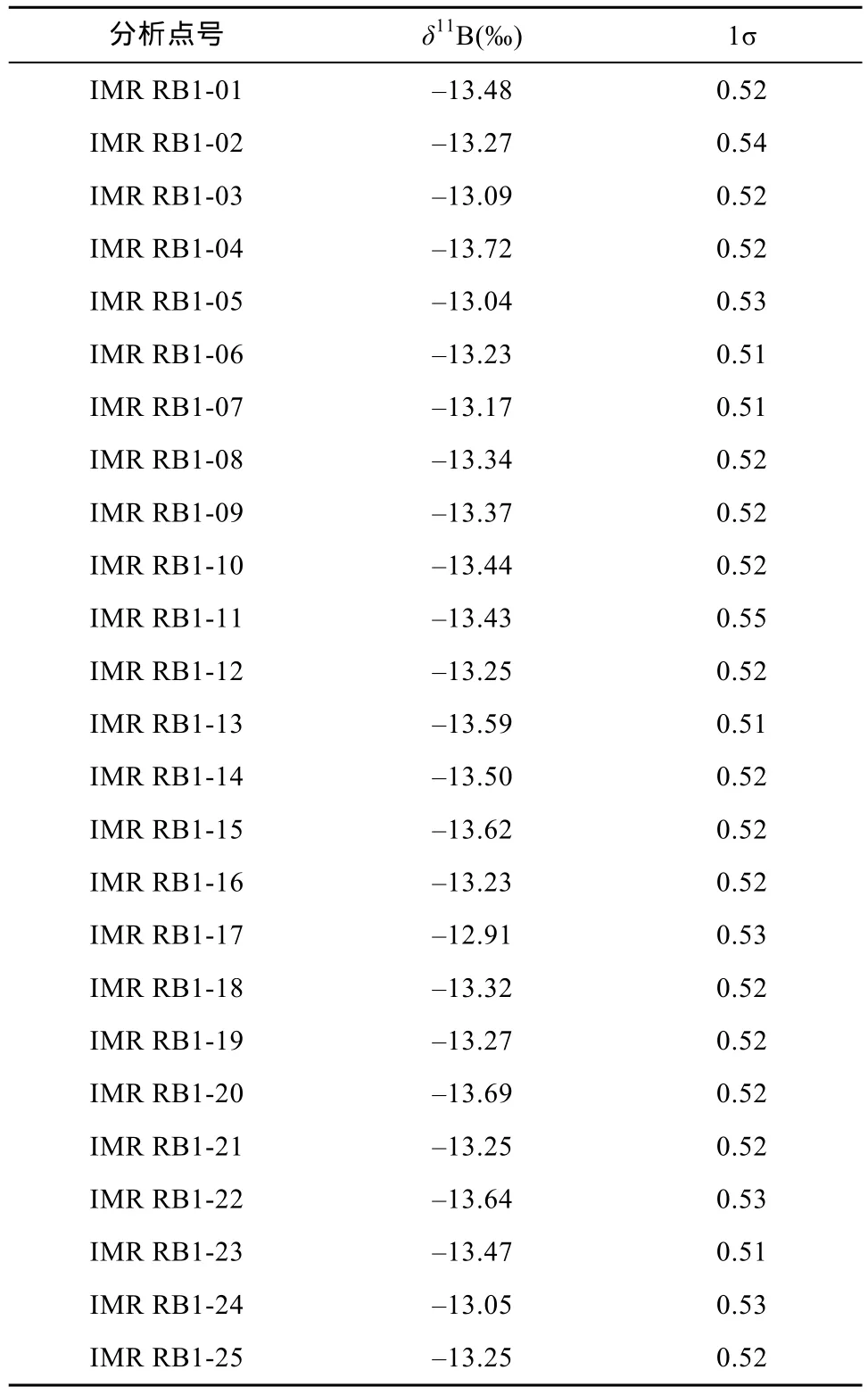

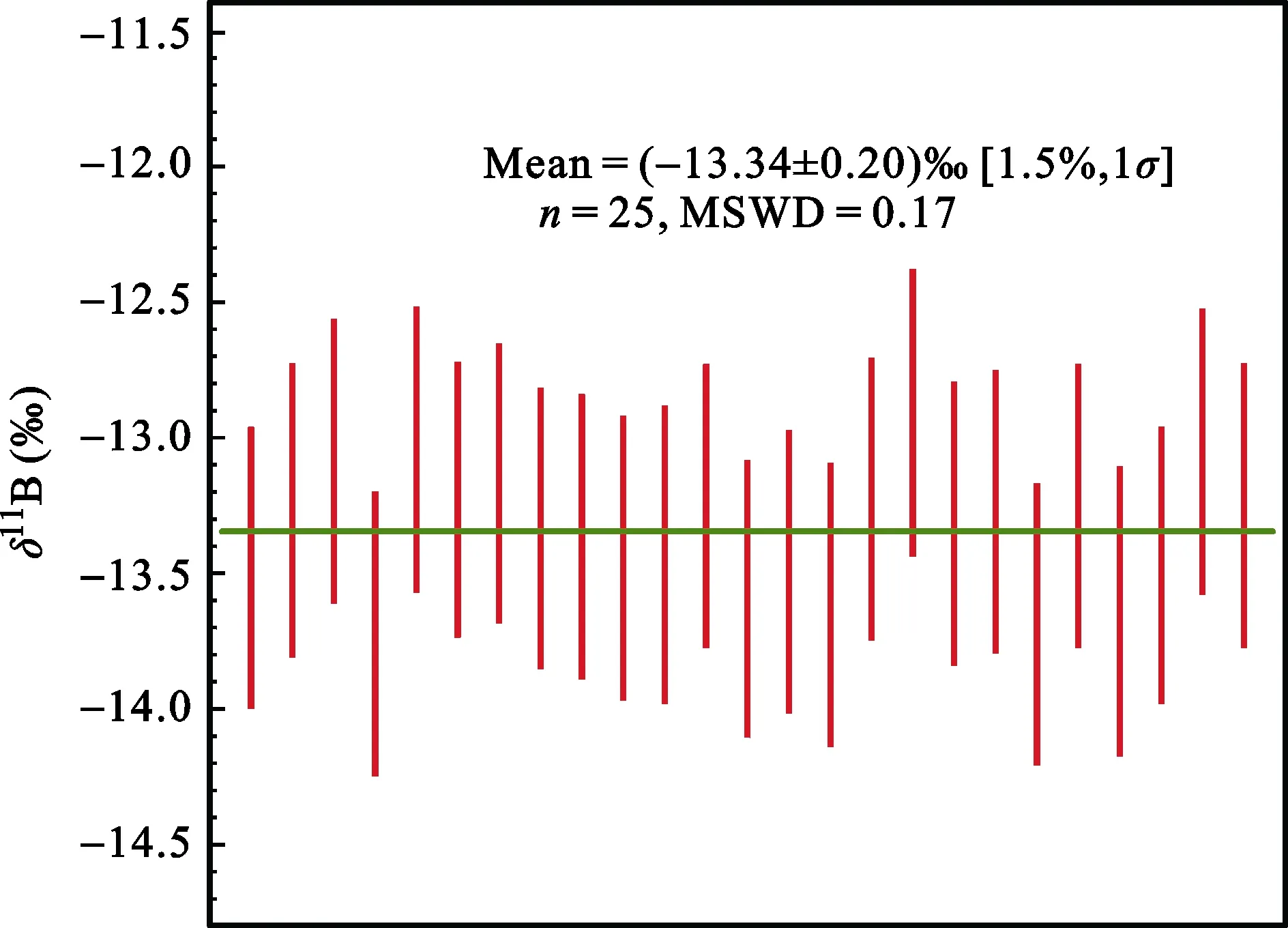

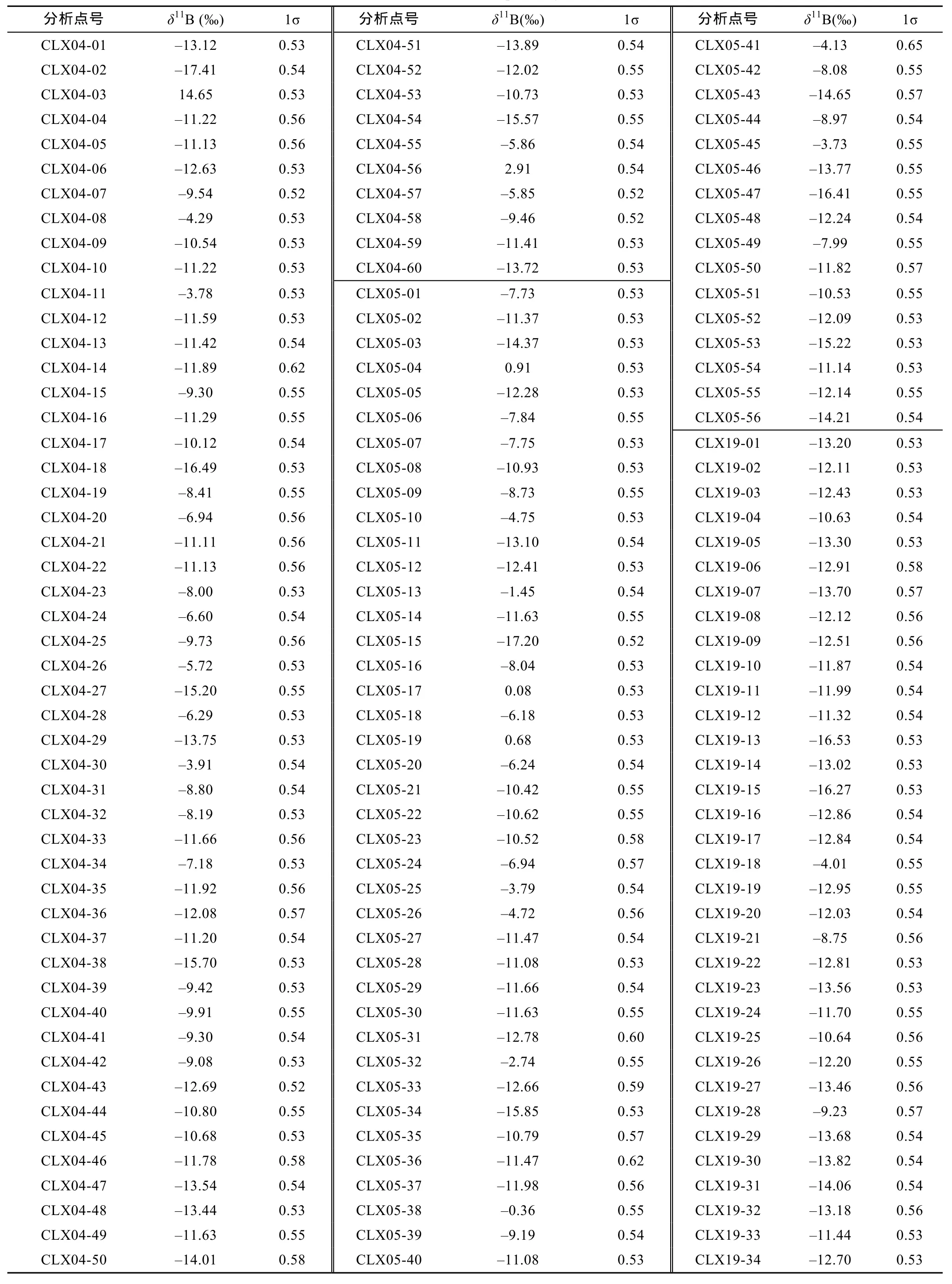

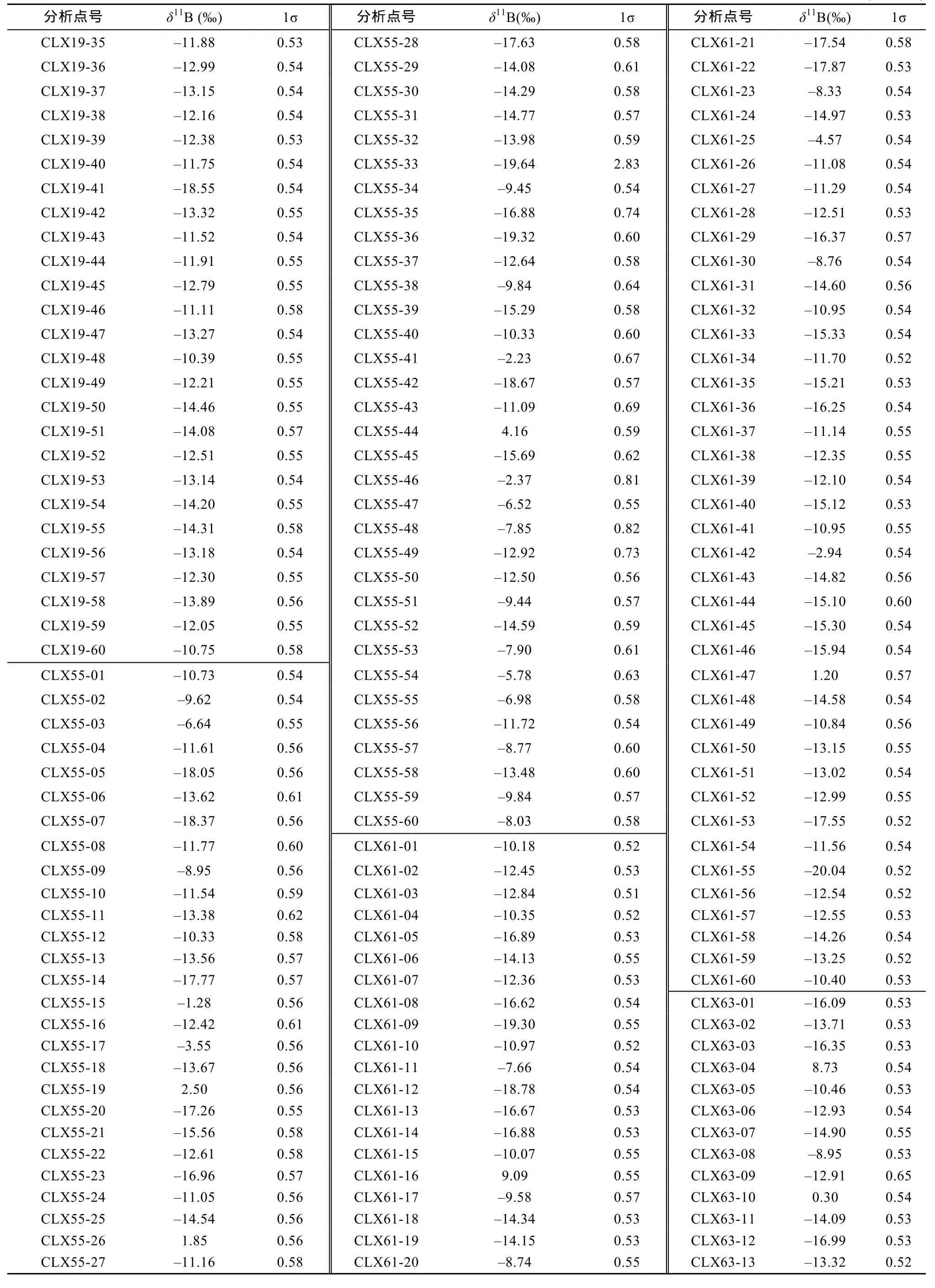

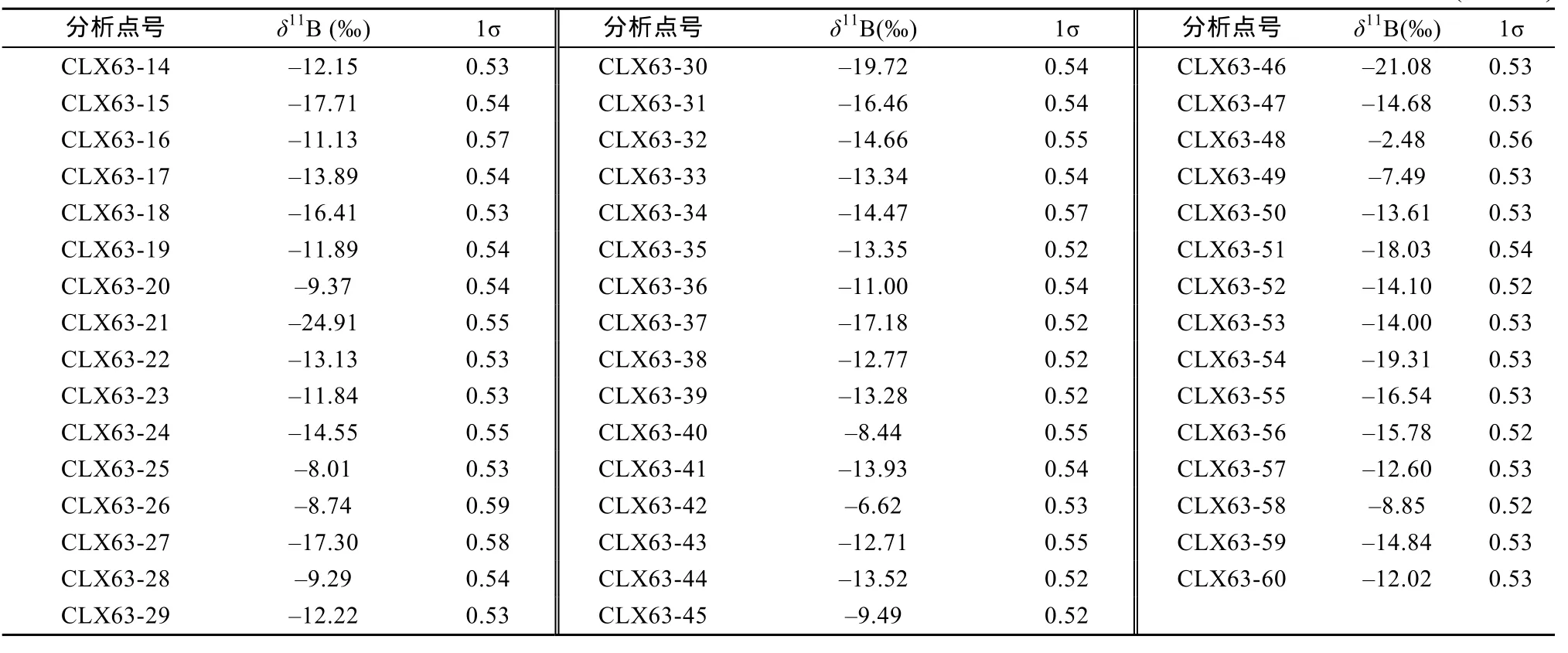

电气石的LA-MC-ICPMS微区原位硼同位素分析测定在中国科学院广州地球化学研究所同位素地球化学国家重点实验室完成。分析所使用的仪器为Thermo Scientific公司生产的Neptune Plus多接收等离子体质谱仪及与之相连接的美国 Resonetics LLC公司生产的RESOlution M-50激光剥蚀系统。激光剥蚀条件为: 束斑直径45 μm, 剥蚀频率5 Hz, 激光输出能量100 mJ, 经过50%的衰减后作用于样品表面。剥蚀产生的气溶胶以He气作为载气带出, 通过三通与Ar气混合载入MC-ICPMS进行离子化。10B和11B分别以法拉第杯L3和H3同时静态接收。正式测定之前先以线扫描国际原子能机构的电气石硼同位素标样IAEA B4[26–27]对仪器参数进行调试, 使之达到最佳状态。数据采集所用的积分时间为0.131 s,共采集400组数据, 包括200组气体空白测试(不开激光), 共耗时约为54 s。每个点分析完成后等待30 s清洗时间再开始下一个点的分析。10B和11B的信号强度在0.5 V和2.3 V左右, 背景信号强度分别小于0.003 V和0.01 V。在分析过程中采用每10个未知样品点前后分别分析 2个标样点, 以 4个标样点的平均值校正未知样品的方法, 来校正仪器质量歧视和同位素分馏。以 IAEA B4 ((δ11B=(–8.71 ± 0.18)‰)为校正标准, 以中国地质科学院矿产资源研究所电气石标样 IMR RB1作为监控标样, 本实验测试中25个IMR RB1分析点给出的δ11B结果(表1)加权平均值为(–13.34±0.20)‰ (1σ, 图 4), 跟侯可军等[32]报道的(–12.96±0.49)‰ (1σ)在误差范围内一致。

图3 样品碎屑电气石BSE图像及对应的δ11B值Fig.3 BSE images of some detrital tourmalines and corresponding δ11B valuesδ11B (‰) = [(11B/10B)样品/(11B/10B)NIST SRM 951-1]×1000, 红色圆圈代表分析点位, 红色数值为 δ11B 值The red circles indicate the analytical spots. Numbers near the analytical spots are the δ11B values

表1 电气石标样IMR RB1硼同位素测试结果Table 1 Analytical results of the tourmaline standard IMR RB1

图4 电气石标样IMR RB1 δ11B分析结果Fig.4 Analytical results of the tourmaline standard IMR RB1

3 分析结果

样品中的碎屑电气石多呈长柱状, 自形到半自形, 长 80~200 μm, 长宽比约为 1∶1 到 2∶1。反射光图像下颜色较为均一, 可见部分包裹体及裂缝。大部分颗粒磨圆较好, 呈次棱角状到次圆状, 显示其在水动力搬运过程中经历了较强的磨蚀作用(图3)。

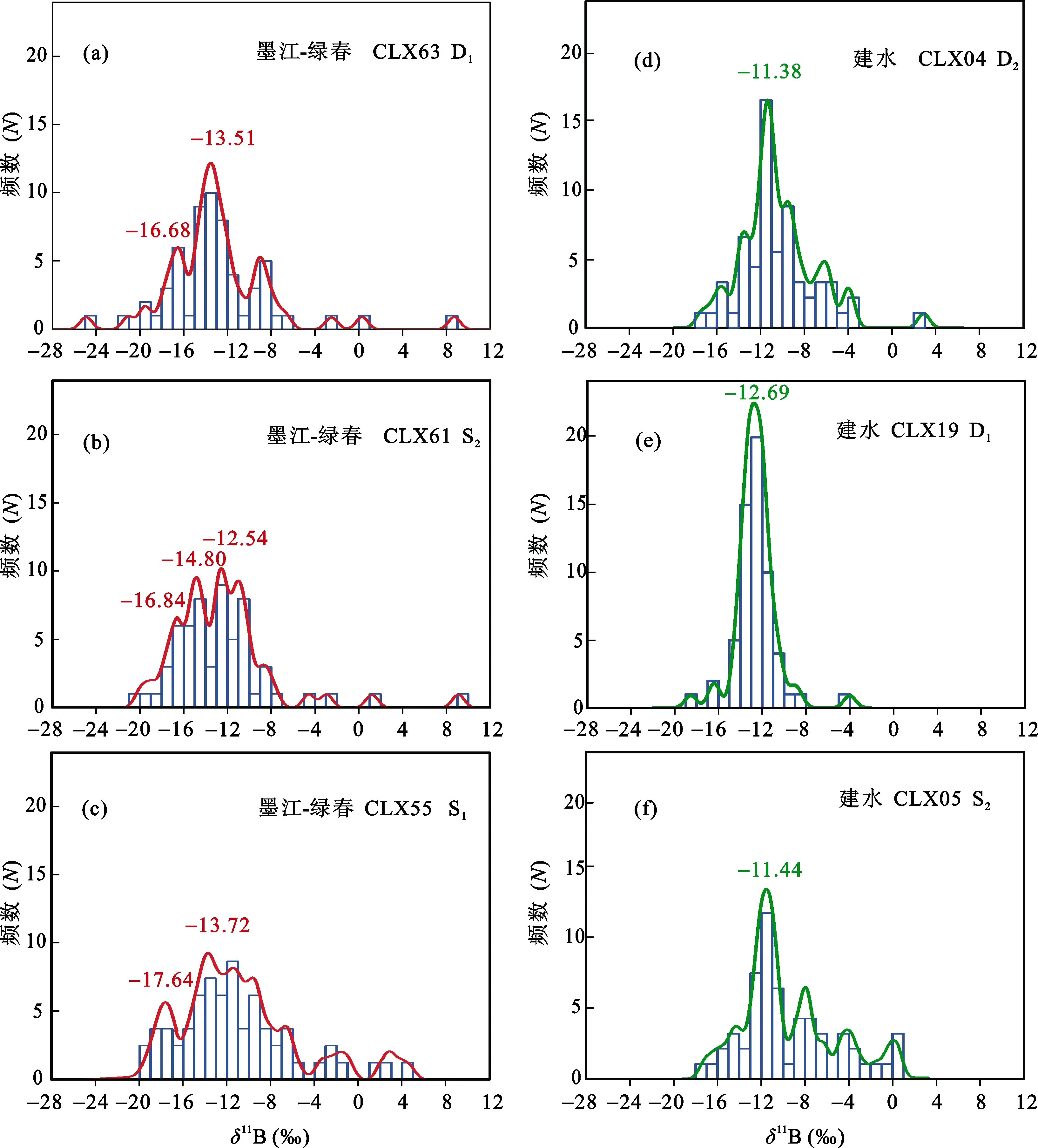

依据透反射光及BSE图像, 在每个碎屑岩样品中随机挑选了约 60颗碎屑电气石进行原位微区硼同位素分析测试, 其详细结果见表 2, 并利用ISOPLOT version 4.7软件[50]对每个样品的碎屑电气石硼同位素绘制概率密度图(图5)。

来自哀牢山构造带内的 3个样品(CLX55,CLX61, CLX63)中的碎屑电气石硼同位素δ11B值均较为分散(图 5a, 图 5b, 图 5c), 大多数电气石δ11B值集中在–21‰ ~ –1‰之间。其中下泥盆统样品CLX63共测定了 60个数据点, 计算的δ11B值介于–24.91‰ ~ 8.73‰之间, 在概率密度图上呈多峰状,主要峰值有–13.51‰和–16.68‰(图 5a); 中志留统样品CLX61共测试了60个数据点, 计算的δ11B值介于–20.04‰~ 9.09‰之间, 在概率密度图上呈多峰状,主要峰值有–12.54‰、–14.80‰和–16.84‰(图 5b);下志留统样品 CXL55共测试了 60个数据点, 计算的δ11B 值在–19.4‰~4.16‰之间, 在概率密度图上呈多峰状, 主要峰值有–13.72‰和–17.64‰ (图 5c)。

来自扬子西缘建水地区的 3个样品(CLX04,CLX05, CLX19)碎屑电气石硼同位素δ11B值均较为集中(图 5d, 图 5e, 图 5f), 大多数电气石δ11B值集中在–14‰ ~ –4‰之间。其中中泥盆统样品CXL04共测试了 60个数据点, 计算的δ11B值在–17.41‰~14.65‰之间, 在概率密度图上呈 1个峰值为–11.38‰主峰和几个较小的峰(图 5d); 中志留统样品CLX05共分析了56个数据点, 计算的δ11B值介于–17.20‰ ~ 0.91‰之间, 在概率密度图上呈1个峰值为–11.44‰的主峰和几个较小峰值(图5e); 下泥盆统样品 CLX19共测定了 60个数据点, 计算的δ11B值介于–18.55‰ ~ –4.01‰之间, 在概率密度图上呈一个峰值为峰值为–12.69‰主峰(图5f)。

4 讨 论

哀牢山构造带内 3个不同时代的样品(CLX55,CLX61, CLX63)的碎屑电气石δ11B值主要集中在–21‰ ~ –1‰, 均呈现多个峰值(图 5a, 图 5b, 图 5c和图 6a), 说明哀牢山构造带内下志留统-下泥盆系碎屑岩可能接受大致相同物源区的剥蚀供给, 而δ11B值分布范围广, 且呈多峰状则可能指示了物源

区组成较为复杂多样。样品中有37%~42%(平均39%)的碎屑电气石δ11B值与来自壳源花岗岩的原生电气石的δ11B 值(–14‰ ~ –10‰)一致[4,13,41,51–53], 反映这些电气石可能来源于壳源花岗岩[4,40]。此前的研究表明 ,结 晶 于 变 质 流 体 中 的 电 气 石 (–16.0‰ ~–17.1‰)[4,40]、经历强烈去气作用演化晚期岩浆中结晶的电气石 (–23‰ ~ –13.9‰)[4,54,55]以及与非海相蒸发岩相关的电气石[56–57]具有轻的硼同位素组成, 因此样品中 30%~44% (平均 38%)具有较轻硼同位素组成(小于–14‰)的碎屑电气石可能来自这些环境。

表2 碎屑电气石硼同位素测试结果Table 2 LA-MC-ICPMS in-situ boron isotopic analyses of detrital tourmalines

(续表 2)

(续表 2)

图5 哀牢山构造带与扬子西缘志留系-泥盆系碎屑岩样品碎屑电气石硼同位素概率密度图Fig.5 Detrital tourmalines δ11B probability histograms for the analyzed samples from the Ailaoshan belt and the western margin of the Yangtze Block

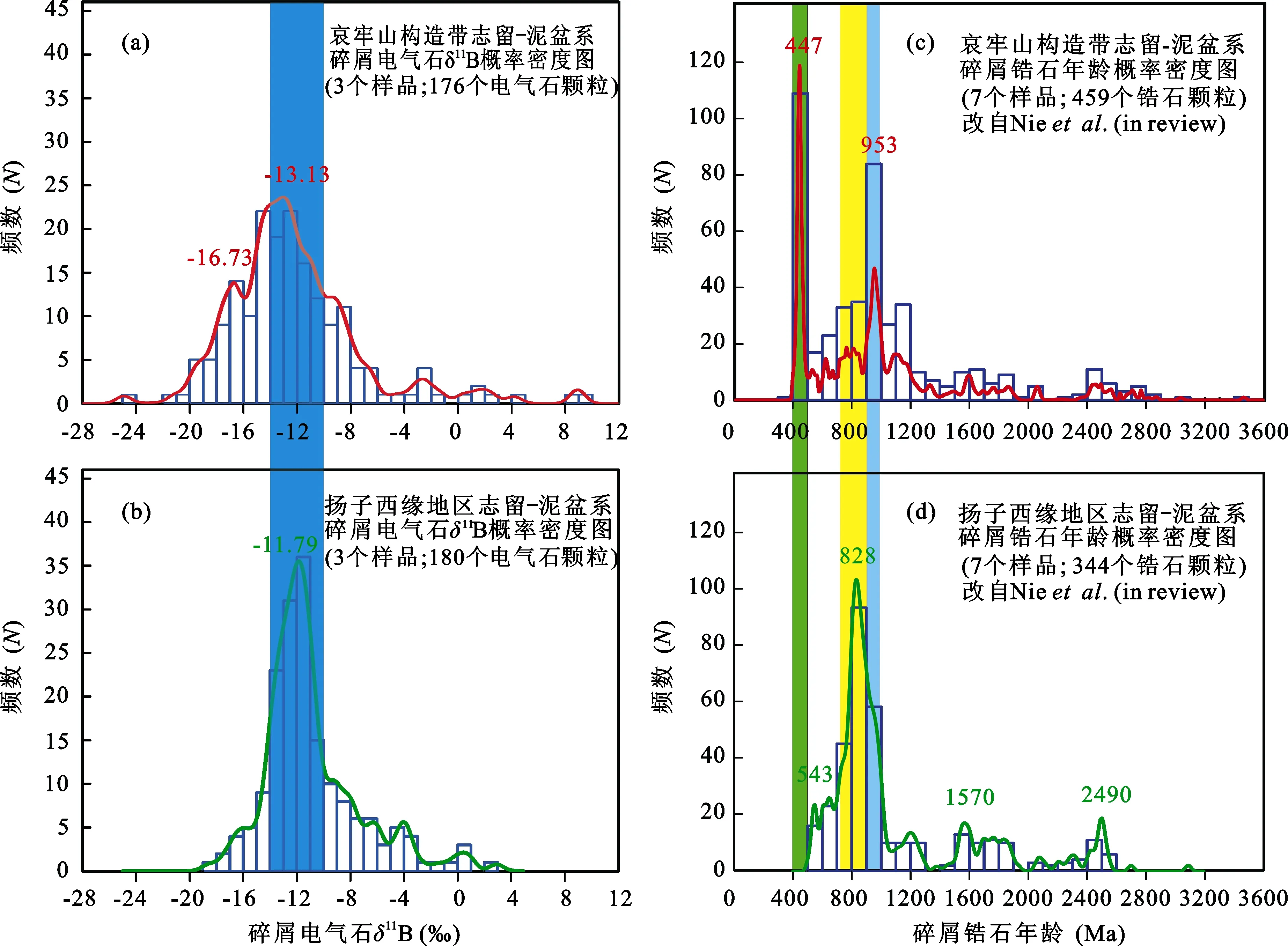

图6 哀牢山构造带与扬子西缘志留-泥盆系样品碎屑锆石年龄(Nie et al., in review)及碎屑电气石硼同位素概率密度图Fig.6 Summary of detrital tourmalines δ11B distributions for this study and detrital zircon age distributions for previous study of sedimentary rocks from the Ailaoshan belt and the western margin of the Yangtze Block

而扬子板块西缘 3个样品(CLX04, CLX05,CLX19)的碎屑电气石硼同位素概率密度图分布较为集中,δ11B 主要集中在–16‰ ~ –1‰, 概率密度图中呈现一个显著主峰, 峰值大约在–12‰(图5d,图5e,图5f, 图6b), 可能指示主要物源较为稳定。3个样品中有 47%~78%(平均 58%)的碎屑电气石具有的δ11B值在来自壳源花岗岩的原生电气石的δ11B(–14‰ ~ –10‰)范围内, 接近大陆地壳值[4], 反映其物源可能主要为壳源花岗岩来源[40]; 扬子西缘样品中小于–14‰的碎屑电气石比例为 10%~16%(平均13%), 明显低于哀牢山构造带内样品, 可能说明这些电气石的寄主岩对物源贡献较低; 而这些样品中较高比例(平均27%)的电气石具有较重硼同位素(大于–10%), 可能其源区受到来自俯冲板片流体[58–60]或者海相碳酸盐岩、蒸发岩的影响更为明显[4,5,61]。

对比两侧碎屑电气石硼同位素数据可以发现,哀牢山构造带内样品所具有的特征与扬子西缘样品显著不同, 哀牢山构造内样品δ11B值较为分散, 相对较轻, 而扬子西缘样品的δ11B值较为集中, 相对较重, 指示两者物源存在明显差异(图5,图6)。这与利用碎屑锆石方法得出的结论较为一致, 即认为特提斯缝合线哀牢山藤条河断裂两侧古生代沉积岩中碎屑锆石年龄谱存在显著差异(图6c,图6d), 缝合线以西思茅一侧志留系-泥盆系碎屑锆石年龄谱极为相似, 年龄主要集中在400~500 Ma和900~1000 Ma,指示碎屑岩物源较为稳定, 但是源区组成较为复杂,可能来自印支地块及冈瓦那大陆北缘[49,62,63]; 而缝合线以东扬子西缘志留系-泥盆系碎屑锆石年龄主要集中在 730~1000 Ma, 指示碎屑岩物源较为稳定且单一, 扬子西缘新元古代汉南-攀西-元江新元古代岩浆弧[45,63–66]可能为其主要源区[63]。

5 结 论

(1) 测定标样 IMR RB1δ11B 值为(–13.34±0.20)‰ (1σ), 与前人报道在误差范围内, 证明我们在中国科学院广州地球化学研究所开发的电气石LA-MC-ICPMS硼同位素分析方法准确可靠。

(2) 哀牢山构造带内古特提斯缝合线以西思茅侧志留系-泥盆系碎屑岩中碎屑电气石硼同位素组成偏轻, 较为分散, 指示源区组成较为复杂。

(3) 古特提斯缝合线以东扬子西缘建水地区志留系-泥盆系碎屑岩中碎屑电气石硼同位素组成偏重, 较为集中, 指示源区较为单一, 且源区可能受到了来自俯冲板片流体或者海相碳酸盐岩、蒸发岩的影响。

(4) 哀牢山构造带古特提斯缝合线两侧碎屑电气石硼同位素特征显著不同, 显示两者物源有明显差异, 哀牢山构造带内的志留系-泥盆系碎屑岩并不是前人所认为的扬子被动大陆边缘的斜坡沉积。

本研究受国家自然科学基金项目(41173007)资助。中国地质科学院矿产资源研究所侯可军博士提供了本次实验中使用的标准电气石样品IAEA B4和IMR RB1; 野外和实验过程中得到了龙晓平研究员、蔡永峰博士的支持和帮助, 在此一并表示感谢。

:

[1] Palmer M R, Swihart G H. Boron isotope geochemistry: An overview[J]. Rev Mineral, 1996, 33(1): 709–744.

[2] Jiang S Y, Palmer M R. Boron isotope systematics of tourmaline from granites and pegmatites: A synthesis[J]. Eur J Mineral, 1998, 10(6): 1253–1265.

[3] Barth S. Boron isotope variations in nature: A synthesis[J].Geol Rundsch, 1993, 82(4): 640–651.

[4] Marschall H R, Jiang S Y. Tourmaline isotopes: No element left behind[J]. Elements, 2011, 7(5): 313–319.

[5] 蒋少涌. 硼同位素及其地质应用研究[J]. 高校地质学报,2000, 6(1): 1–16.Jiang Shao-yong. Boron isotope and its geological applications[J]. Geol J China Univ, 2000, 6(1): 1–16 (in Chinese with English abstract).

[6] Eppich G R, Singleton M J, Wimpenny J B, Yin Q Z, Bradley K E. California GAMA Special Study: Stable isotopic composition of boron in groundwater-San Diego County Domestic Well Data[R]. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), Livermore, CA, 2012.

[7] Wei G J, McCulloch M T, Mortimer G, Deng W F, Xie L H.Evidence for ocean acidification in the Great Barrier Reef of Australia[J]. Geochim Cosmochim Acta, 2009, 73(8):2332–2346.

[8] Wei H Z, Jiang S Y, Tan H B, Zhang W J, Li B K, Yang T L.Boron isotope geochemistry of salt sediments from the Dongtai salt lake in Qaidam Basin: Boron budget and sources[J]. Chem Geol, 2014, 380: 74–83.

[9] Yuan J, Guo Q, Wang Y. Geochemical behaviors of boron and its isotopes in aqueous environment of the Yangbajing and Yangyi geothermal fields, Tibet, China[J]. J Geochem Explor,2014, 140: 11–22.

[10] Bast R, Scherer E E, Mezger K, Austrheim H, Ludwig T,Marschall H R, Putnis A, Löwen K. Boron isotopes in tourmaline as a tracer of metasomatic processes in the Bamble sector of Southern Norway[J]. Contrib Mineral Petrol, 2014,168(4): 1–21.

[11] Genske F S, Turner S P, Beier C, Beier C, Chu Mei-Fei,Tonarini S, Pearson N J, Haase K M. Lithium and boron isotope systematics in lavas fromthe Azores islands reveal crustal assimilation[J]. Chem Geol, 2014, 373: 27–36.

[12] Jones R E, de Hoog J C M, Kirstein L A, Kasemann S A,Hinton R, Elliott T, Litvak V D, EIMF. Temporal variations in the influence of the subducting slab on Central Andean arc magmas: Evidence from boron isotope systematics[J]. Earth Planet Sci Lett, 2014, 408: 390–401.

[13] Yang S Y, Jiang S Y. Chemical and boron isotopic omposition of tourmaline in the Xiangshan volcanic-intrusive complex,Southeast China: Evidence for boron mobilization and infiltration during magmatic-hydrothermal processes[J].Chem Geol, 2012, 312: 177–189.

[14] Hu Guyue, Li Yanhe, Fan Changfu, Hou Kejun, Zhao Yue,Zeng Lingsen.In situLA-MC-ICP-MS boron isotope and zircon U-Pb age determinations of Paleoproterozoic borate deposits in Liaoning Province, northeastern China[J]. Ore Geol Rev, 2015, 65: 1127–1141.

[15] Slack J F, Trumbull R B. Tourmaline as a recorder of ore-forming processes[J]. Elements, 2011, 7(5): 321–326.

[16] Swihart G H, Carpenter S B, Xiao Yun, McBay E H, Smith D H, Xiao Yingkai. A boron isotope study of the Furnace Creek,California, borate district[J]. Econ Geol, 2014, 109(3):567–580.

[17] Wang F L, Wang C Y, Zhao T P. Boron isotopic constraints on the Nb and Ta mineralization of the syenitic dikes in the ~260 Ma Emeishan large igneous province (SW China)[J]. Ore Geol Rev, 2015, 65: 1110–1126.

[18] Yan X, Chen B. Chemical and boron isotopic compositions of tourmaline from the Paleoproterozoic Houxianyu borate deposit, NE China: Implications for the origin of borate deposit[J]. J Asian Earth Sci, 2014, 94: 252–266.

[19] MacGregor J R, Grew E S, de Hoog J C M, Harley S L,Kowalski P M, Yates M G, Carson C J. Boron isotopic composition of tourmaline, prismatine, and grandidierite from granulite facies paragneisses in the Larsemann Hills, PrydzBay, East Antarctica: Evidence for a non-marine evaporite source[J]. Geochim Cosmochim Acta, 2013, 123: 261–283.

[20] Tan Hongbing, Ma Haizhou, Li Binkai, Zhang Xiying, Xiao Yingkai. Strontium and boron isotopic constraint on the marine origin of the Khammuane potash deposits in southeastern Laos[J]. Chinese Sci Bull, 2010, 55(27/28):3181–3188.

[21] Zhang X, Ma H, Ma Y, Tang Q, Yuan X. Origin of the late Cretaceous potash-bearing evaporites in the Vientiane Basin of Laos:δ11B evidence from borates[J]. J Asian Earth Sci,2013, 62: 812–818.

[22] Kasemann S A, Schmidt D N, Bijma J, Foster G L.In situboron isotope analysis in marine carbonates and its application for foraminifera and palaeo-pH[J]. Chem Geol,2009, 260(1): 138–147.

[23] Liu Y, Liu W, Peng Z, Xiao Y K, Wei G J, Sun W D, He JF,Liu G J, Chou C L. Instability of seawater pH in the South China Sea during the mid-late Holocene: Evidence from boron isotopic composition of corals[J]. Geochim Cosmochim Acta, 2009, 73(5): 1264–1272.

[24] Wei H Z, Lei F, Jiang S Y, Lu H Y, Xiao Y K, Zhang H Z, Sun X F. Implication of boron isotope geochemistry for the pedogenic environments in loess and paleosol sequences of central China[J]. Quatern Res, 2015, 83(1): 243–255.

[25] Pagani M, Lemarchand D, Spivack A, Gaillardet J. A critical evaluation of the boron isotope-pH proxy: The accuracy of ancient ocean pH estimates[J]. Geochim Cosmochim Acta,2005, 69(4): 953–961.

[26] Tonarini S, Pennisi M, Adorni-Braccesi A, Dini A, Ferrara G,Gonfiantini R, Wiedenbeck M, Gröning M. Intercomparison of boron isotope and concentration measurements. Part I:Selection, preparation and homogeneity tests of the intercomparison materials[J]. Geostand Newslett, 2003, 27(1):21–39.

[27] Gonfiantini R, Tonarini S, Gröning M, Adorni-Braccesi A,Al-Ammar A S, Astner M, Bächler S, Barnes R M, Bassett R L, Cocherie A. Intercomparison of boron isotope and concentration measurements. Part II: Evaluation of results[J].Geostand Newslett, 2003, 27(1): 41–57.

[28] Chaussidon M, Robert F, Mangin D, Hanon P, Rose E F.Analytical procedures for the measurement of boron isotope compositions by ion microprobe in meteorites and mantle rocks[J]. Geostand Newslett, 1997, 21(1): 7–17.

[29] Fietzke J, Heinemann A, Taubner I, Böhm F, Erez J,Eisenhauer A. Boron isotope ratio determination in carbonates via LA-MC-ICP-MS using soda-lime glass standards as reference material[J]. J Anal Atom Spectrom, 2010, 25(12):1953–1957.

[30] Kobayashi K, Tanaka R, Moriguti T, Shimizu K, Nakamura E.Lithium, boron, and lead isotope systematics of glass inclusions in olivines from Hawaiian lavas: Evidence for recycled components in the Hawaiian plume[J]. Chem Geol,2004, 212(1): 143–161.

[31] Le Roux P, Shirey S, Benton L, Hauri E, Mock T.In situ,multiple-multiplier, laser ablation ICP-MS measurement of boron isotopic composition (δ11B) at the nanogram level[J].Chem Geol, 2004, 203(1): 123–138.

[32] 侯可军, 李延河, 肖应凯, 刘峰, 田有荣. LA-MC-ICP-MS硼同位素微区原位测试技术[J]. 科学通报, 2010, 55(22):2207–2213.Hou Kejun, Li Yanhe, Xiao Yingkai, Liu Feng, Tian Yourong.LA-MC-ICP-MSin-situboron isotope measure technique[J].Chinese Sci Bull, 2010, 55(22): 2207–2213 (in Chinese).

[33] van Hinsberg V J, Henry D J, Dutrow B L. Tourmaline as a petrologic forensic mineral: A unique recorder of its geologic past[J]. Elements, 2011, 7(5): 327–332.

[34] Henry D J, Dutrow B L. Metamorphic tourmaline and its petrologic applications[J]. Rev Mineral, 1996, 33(1): 503–557.

[35] Henry D J, Guidotti C V. Tourmaline as a petrogenetic indicator mineral: An example from the staurolite-grade metapelites of NW Maine[J]. Am Mineral, 1985, 70(1/2): 1–15.

[36] Morton A C, Hallsworth C R. Processes controlling the composition of heavy mineral assemblages in sandstones[J].Sediment Geol, 1999, 124(1): 3–29.

[37] Morton A C, Whitham A G, Fanning C M. Provenance of Late Cretaceous to Paleocene submarine fan sandstones in the Norwegian Sea: Integration of heavy mineral, mineral chemical and zircon age data[J]. Sediment Geol, 2005, 182(1):3–28.

[38] Salata D. Detrital tourmaline as an indicator of source rock lithology: An example from the Ropianka and Menilite formations (Skole Nappe, Polish Flysch Carpathians)[J]. Geol Q, 2013, 58(1): 19–30.

[39] Morton A C, Meinhold G, Howard J P, Phillips R J, Strogen D,Abutarruma Y, Elgadry M, Thusu B, Whitham A G. A heavy mineral study of sandstones from the eastern Murzuq Basin,Libya: Constraints on provenance and stratigraphic correlation[J]. J Afr Earth Sci, 2011, 61(4): 308–330.

[40] Jiang S Y, Radvanec M, Nakamura E, Palmer M, Kobayashi K,Zhao H X, Zhao K D. Chemical and boron isotopic variations of tourmaline in the Hnilec granite-related hydrothermal system, Slovakia: Constraints on magmatic and metamorphic fluid evolution[J]. Lithos, 2008, 106(1): 1–11.

[41] 郭海锋, 夏小平, 韦刚健, 王强, 赵振华, 黄小龙, 张海祥,袁超, 李武显. 湘南上堡花岗岩中电气石 LA-MC-ICPMS原位微区硼同位素分析及地质意义[J]. 地球化学, 2014,43(1): 11–19.Guo Hai-feng, Xia Xiao-ping, Wei Gang-jian, Wang Qiang,Zhao Zhen-hua, Huang Xiao-long, Zhang Hai-xiang, Yuan Chao, Li Wu-xian. LA-MC-ICPMSin situboron isotopic analyses of tourmalines from the turmaline-bearing granites in the Shangbao area (southern Hunan Province) and its geological significance[J]. Geochimica, 2014, 43(1): 11–19(in Chinese with English abstract).

[42] 钟大赉. 滇川西部古特提斯造山带[M]. 北京: 科学出版社,1998: 1–231.Zhong Da-lai. Paleotethyan Orogeny in the Western Yunnan and Sichuan[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 1998: 1–231 (inChinese with English abstract).

[43] 刘俊来, 唐渊, 宋志杰, 翟云峰, 吴文彬, 陈文. 滇西哀牢山构造带: 结构与演化[J]. 吉林大学学报: 地球科学版,2011, 41(5): 1285–1303.Liu Jun-lai, Tang Yuan, Song Zhi-jie, Zhai Yun-feng, Wu Wen-bin, Chen Wen. The Ailaoshan belt in western Yunnan:Tectonic framework and tectonic evolution[J]. J Jilin Univ(Earth Sci), 2011, 41(5): 1285–1303 (in Chinese with English abstract).

[44] 董云鹏, 朱炳泉. 哀牢山缝合带中两类火山岩地球化学特征及其构造意义[J]. 地球化学, 2000, 29(1): 6–13.Dong Yun-peng, Zhu Bing-quan. Geochemistry of the two-type volcanic rocks from Ailaoshan suture zone and their tectonic implication[J]. Geochimica, 2000, 29(1): 6–13 (in Chinese with English abstract).

[45] Tapponnier P, Lacassin R, Leloup P H, Schärer U, Zhong Dalai,Wu Haiwei, Liu Xiaohan, Ji Shaocheng, Zhang Lianshang,Zhong Jiayou. The Ailao Shan/Red River metamorphic belt:Tertiary left-lateral shear between Indochina and South China[J].Nature, 1990, 343(6257): 431–437.

[46] Cai Yongfeng, Wang Yuejun, Cawood P A, Fang Weiming,Liu Huichuan, Xing Xiaowan, Zhang Yuzhi. Neoproterozoic subduction along the Ailaoshan zone, South China:Geochronological and geochemical evidence from amphibolite[J]. Precamb Res, 2014, 245: 13–28.

[47] Liu F, Wang F, Liu P, Liu, C. Multiple metamorphic events revealed by zircons from the Diancang Shan-Ailao Shan metamorphic complex, southeastern Tibetan Plateau[J].Gondwana Res, 2013, 24(1): 429–450.

[48] 云南省地质矿产局. 云南省区域地质志[M]. 北京: 地质出版社, 1990: 21.Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources of Yunnan Province. Regional Geology of Yunnan Province[M]. Beijing:Geological Publishing House, 1990: 21 (in Chinese).

[49] Wang Q F, Deng J, Li C S, Li G J, Yu L, Qiao L. The boundary between the Simao and Yangtze blocks and their locations in Gondwana and Rodinia: Constraints from detrital and inherited zircons[J]. Gondwana Res, 2013, 26(2): 438–448.

[50] Ludwig K R. Isoplot 3.0 — A geochronological toolkit for Microsoft Excel[R]. Berkeley Geochronology Center Special Publication, 2003.

[51] Kasemann S, Erzinger J, Franz G. Boron recycling in the continental crust of the central Andes from the Palaeozoic to Mesozoic, NW Argentina[J]. Contrib Mineral Petrol, 2000,140(3): 328–343.

[52] Talikka M, Vuori S. Geochemical and boron isotopic compositions of tourmalines from selected gold-mineralized and barren rocks in SW Finland[J]. Bull Geol Soc Finland,2010, 82(2): 113–128.

[53] Zhao K D, Jiang S Y, Nakamura E, Moriguti T, Palmer M R,Yang S Y, Dai B Z, Jiang Y H. Fluid-rock interaction in the Qitianling granite and associated tin deposits, South China:Evidence from boron and oxygen isotopes[J]. Ore Geol Rev,2011, 43(1): 243–248.

[54] Jiang S Y. Boron isotope geochemistry of hydrothermal ore deposits in China: A preliminary study[J]. Phys Chem Earth Solid Earth Geodes, 2001, 26(9): 851–858.

[55] Trumbull R B, Chaussidon M. Chemical and boron isotopic composition of magmatic and hydrothermal tourmalines from the Sinceni granite-pegmatite system in Swaziland[J]. Chem Geol, 1999, 153(1): 125–137.

[56] Slack J F, Palmer M R, Stevens B P J. Boron isotope evidence for the involvement of non-marine evaporites in the origin of the Broken Hill ore deposits[J]. Nature, 342(6252): 913–916.

[57] Palmer M R, Slack J F. Boron isotopic composition of tourmaline from massive sulfide deposits and tourmalinites[J].Contrib Mineral Petrol, 1989, 103(4): 434–451.

[58] Altherr R, Topuz G, Marschall H, Zack T, Ludwig T.Evolution of a tourmaline-bearing lawsonite eclogite from the Elekdağ area (Central Pontides, N Turkey): Evidence for infiltration of slab-derived B-rich fluids during exhumation[J].Contrib Mineral Petrol, 2004, 148(4): 409–425.

[59] Peacock S M, Hervig R L. Boron isotopic composition of subduction-zone metamorphic rocks[J]. Chem Geol, 1999,160(4): 281–290.

[60] Scambelluri M, Tonarini S. Boron isotope evidence for shallow fluid transfer across subduction zones by serpentinized mantle[J]. Geology, 2012, 40(10): 907–910.

[61] Pal D C, Trumbull R B, Wiedenbeck M. Chemical and boron isotope compositions of tourmaline from the Jaduguda U(-Cu-Fe) deposit, Singhbhum shear zone, India: Implications for the sources and evolution of mineralizing fluids[J]. Chem Geol, 2010, 277(3): 245–260.

[62] Burrett C, Zaw K, Meffre S, Lai C K, Khositanont S,Chaodumrong P, Udchachon M, Ekins S, Halpin J. The configuration of Greater Gondwana — Evidence from LA ICPMS, U-Pb geochronology of detrital zircons from the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic of Southeast Asia and China[J].Gondwana Res, 2014, 26(1): 31–51.

[63] Nie Xiaosong, Xia Xiaoping, Lai Chun-Kit, Wang Yuejun,Long Xiaoping. Where was the Ailaoshan Ocean and when did it open: A perspective based on detrital zircon evidence from the Paleozoic sequences in the Ailaoshan Belt and western Yangtze Block[J]. Gondwana Res (in review).

[64] Sun W H, Zhou M F, Gao J F, Yang Y H, Zhao X F, Zhao J H.Detrital zircon U-Pb geochronological and Lu-Hf isotopic constraints on the Precambrian magmatic and crustal evolution of the western Yangtze Block, SW China[J].Precamb Res, 2009, 172(1): 99–126.

[65] Zhao J H, Zhou M F. Geochemistry of Neoproterozoic mafic intrusions in the Panzhihua district (Sichuan Province, SW China): Implications for subduction-related metasomatism in the upper mantle[J]. Precamb Res, 2007, 152(1): 27–47.

[66] Zhou M F, Yan D P, Kennedy A K, Li Y, Ding J. SHRIMP U-Pb zircon geochronological and geochemical evidence for Neoproterozoic arc-magmatism along the western margin of the Yangtze Block, South China[J]. Earth Planet Sci Lett,2002, 196(1): 51–67.

——一个不整合面的地质属性推论