淡水水生态基准方法学研究:繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物水生态基准探讨

金小伟,王子健, 王业耀, 刘娜

1. 中国环境监测总站,北京 100012 2. 中国科学院生态环境研究中心,北京 100085 3. 中国地质大学(北京), 北京 100083

淡水水生态基准方法学研究:繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物水生态基准探讨

金小伟1,王子健2,*, 王业耀1, 刘娜3

1. 中国环境监测总站,北京 100012 2. 中国科学院生态环境研究中心,北京 100085 3. 中国地质大学(北京), 北京 100083

繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物由于特殊的毒理作用模式(mode of action, MOA),通过影响生物繁衍影响到种群和群落,因此依靠基于急、慢性毒性测试终点和传统基准推导方法推导的水生态基准值并不能够为水生生物群落结构提供足够的保护。本文根据文献资料,分析了推导此类化合物水生态基准时的关键科学问题,包括繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物MOA,毒性数据类型,受试物种选择,以及不同生命阶段、多代毒性测试和测试终点的判别和选择。并用所收集的壬基酚数据,尝试推导了基于水生生物生殖毒性的水生态基准值。研究得出基于生殖毒性的壬基酚预测无观察效应浓度(PNEC)值为0.12 μg·L-1,其数值比美国环境保护局根据传统基准方法推导的基准持续浓度(CCC)的6.59 μg·L-1低了近50倍。因此,基于其繁殖毒性(包括产卵量、受精率、孵化率、多代效应以及种群变化等)的实验结果更适合用于具有繁殖/生殖毒性污染物水生态基准的推导。

壬基酚;内分泌干扰物;淡水生物;繁殖/生殖毒性;水质基准

具有繁殖/生殖毒性的环境污染物主要是环境内分泌干扰物,对水生生物(尤其是鱼类)的生殖系统,包括其排卵、生精,从生殖细胞分化到整个细胞发育、胚胎发育导致不同程度的损害,引起生殖系统功能和结构的变化;并因此影响生殖/繁殖能力、雄性化或雌性化,进而累及子代繁衍,影响到整个水生生物群落结构,破坏水生态系统的完整性。越来越多的证据表明,许多具有内分泌干扰效应的外源性化学物质,如工业、农业排放和生活污染源中的内分泌干扰物,通过不同途径进入水生生态环境中。例如,人工合成的乙烯雌酚(diethylstilbestrol, DES)开始进入临床,并在20世纪60—70年代被频繁使用以防止流产,然而几十年后发现服药的女性易患乳腺癌,其子女也易患生殖系统癌症[1]。20世纪40年代,人们发现白三叶植株中含有香豆素衍生物等植物雌激素,食用这种植物的绵羊不孕率及生殖系统疾病发病率上升[2]。20世纪70—80年代,随着工农业快速发展,人类向环境中排放了大量农药、工业废水等,进而引发了大量生物生殖发育异常现象,美国佛罗里达州Apopka湖5年间90%的短吻鳄(Alligator spp)消失,剩余雄鳄阴茎长度只为正常的75%,体内睾丸酮含量显著下降,雌鳄的子宫及卵泡异常,在其蛋黄里检测出二氯二苯三氯乙烷(DDT)和二氯苯基二氯乙烯(DDE)[3]。近年来,有关通过生活污水排放进入天然水体的药物和个人护理用品(pharmaceuticals and personal care products, PPCPs)类物质的文献报道越来越多,导致如英国城市污水处理厂下游河流中捕获到具有雌雄两性特征斜齿鳊鱼(R. rutilus),日本东京附近多摩川中贝类具有两性特征,鲤鱼生殖器畸形[4]。这些PPCPs类物质中,类雌激素已被证实可引起水体中雄性鱼的卵黄蛋白原增加,并出现明显的雌性化[5-7]。研究表明,即使出水中含有1 ng·L-1低剂量的人工合成雌激素17a-乙炔基雌二醇(EE2),也会干扰正常的内分泌,并导致鱼类的雌性化[8]。同时,Gooding等[9]研究了多环麝香对淡水中幼期河蚌的毒性试验,发现佳乐麝香(HHCB)和吐纳麝香(AHTN)对河蚌的繁殖和生长有一定程度的抑制。另有研究表明,HHCB可以通过江豚胎盘转移至胎儿体内[10]。孙立伟等[11]研究发现来曲唑在低剂量下就能够对青鳉鱼(Oryzias latipes)的生殖和早期发育产生明显的影响。查金苗等[12]发现在连续三代暴露于0.2 ng·L-1乙炔基雌二醇后,稀有鮈鲫(Gobiocypris rarus)雄性个体完全消失。这些初步的研究结果揭示出这些具有内分泌干扰效应、生殖/繁殖毒性效应[13]物质的毒理学作用机制不同于基线毒物,对其环境管理也成为一项十分复杂的任务。

水生态基准作为建立水质标准的科学基础和水环境管理的重要依据,成为国内目前研究的热点[14-17]。然而针对繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物(chemicals causing reproductive toxicity, CCR),由于其特殊的毒理作用模式,目前尚没有完善的水生态基准推导方法。Caldwell等[18]从39篇已发表的文献中整理了29个水生物种基于生殖效应的慢性毒性数据,并利用物种敏感度分布曲线法推导了17α-乙炔雌二醇(EE2)的预测无观察效应浓度(predicted no effect concentration, PNEC)值为0.35 ng·L-1。而当毒性数据不足时,按照传统的生存或生长抑制为测试指标推导的EE2的PNEC值0.13 mg·L-1,比基于生殖效应推导的结果高出几十万倍。美国环境保护局(US EPA)于2005年制定了关于壬基酚(nonyl phenol, NP)水生态基准的纲领文件中规定,由于慢性毒性数据的缺乏,利用急慢性毒性比的方法计算获得基准持续浓度(criteria continuous concentration, CCC),规定长期持续暴露可接受的壬基酚CCC为6.59 μg·L-1[19]。部分学者的研究显示当NP的浓度为1 μg·L-1甚至更低0.1 μg·L-1时会对水生生物的生殖系统产生不同程度的影响[20]。同时一些学者认为传统的US EPA水生态基准的推导方法已经过于陈旧,使用急慢性比的方法预测慢性毒性结果一直存在争议,因为在一定程度上,利用平均急慢性比不能够准确地从急性毒性结果外推到慢性毒性结果[21-22]。随着科学研究的不断发展,内分泌干扰物质以及其他激素类物质的在水体中被检测出来,不断的有新的化合物被发现有生殖毒性效应,研究发现仅仅依靠传统基准推导方法和毒性测试终点推导的水生态基准值并不能够为水生生物提供足够的保护。

在脊椎动物体内,生殖受下丘脑-垂体-性腺轴(hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis)的调控[23]。除了核心的雌激素和雄激素,该系统还包含更多的组织及生化机制来支配脊椎动物的性发育,成熟和繁殖。繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物的干扰不限于直接结合到雌激素或雄激素受体,同时也包括在整体生化路径的相互作用。和其他麻醉毒性类化合物以及亲电物质不同,HPG活性化合物往往具有与生化途径中的特定分子靶特异性的相互作用。繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物的靶特异性往往也决定了这类化合物水生态基准的推导,这类化合物往往具有较小的急性毒性,却即使在较低剂量的暴露下有明显的慢性或亚致死效应[24-25]。这直接影响到水生态基准推导过程中急慢性比(acute to chronic ratios, ACRs)方法的使用。传统化合物的ACRs约为10[13, 26],与此相反,EE2和17β-trenbolone(孕三烯酮)针对鱼类实验获得的ACRs范围从1 000至大于300 000[27]。繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物的靶特异性同时有可能影响不同生物类群对特定作用模式(mode of action, MOA)的敏感性差异。一些生物作用途径(如能量代谢)通常存在于所有的生物体,而有的可能是特定于某些亲缘群体。基于HPG轴的控制生殖功能往往适用于脊椎动物,而对于低分类群,如无脊椎动物则具有不同的内分泌系统结构和功能。Segner等[28]研究证明对于EE2,鱼类比无脊椎动物更为敏感。因此在EE2水生态基准的推导过程中,鱼类慢性毒性数据所起的作用至关重要。此外,特定的作用模式也会影响毒性试验结果的表达,即使是潜在的敏感物种。HPG活性化合物对生物全生命周期的实验过程中一般有2个敏感的阶段:幼体发育性分化阶段和成熟个体繁殖阶段[29]。因此,繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物毒性试验过程中选择敏感的测试阶段尤为重要。

本文针对繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物特殊的作用模式,通过探讨繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物水生态基准推导过程中需要注意的关键科学问题,如:毒性数据类型,受试物种选择,以及不同生命阶段、多代毒性测试和测试终点的判别和选择等。并以壬基酚为例,基于生殖毒性结果推导壬基酚预测无观察效应浓度值,以期为繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物水质基准的制定和风险管理提供科学依据。

1 繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物水生态基准推导关键科学问题

1.1 毒性数据类型的判别

在推导水生态基准时,急性毒性数据一般有2个用途:(1)用于直接推导短期暴露基准(或基准最大浓度,criteria maximum concentration, CMC);(2)当慢性毒性数据不足时,用最终急慢性比(final acute to chronic ratio, FACR)的方法推导长期暴露基准(或基准持续浓度,criteria continuous concentration, CCC)。然而从理论上讲,对于一些特殊污染物,如果短期暴露基准超过长期暴露基准的96倍,则一般认为使用长期暴露基准更适合于此类化合物的限值。因为这标准的实施过程中,CMC和CCC分别被定义为1 h和4 d的平均时间内污染物浓度不可超过的标准限值[30]。如果它们之间的差距超过96倍,当污染物浓度不超过CCC的条件下理论上也不会超过CMC[31]。因此对于这一类急性毒性和慢性毒性结果存在极端差异的特殊污染物,在推导水生态基准时只推导一个长期暴露基准似乎更为合理。

由于急性毒性和慢性毒性的致毒机制不同,使得繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物具有独特作用模式以及较大的ACR。另外,不同生物类群生物对繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物急慢性毒性的敏感性也存在差异[28],从而增加了FACR方法的不确定性。因此,从水生态基准方法学的角度看,一旦ACR高于10[31],尤其是针对繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物似乎不宜使用最终急性值(FAV)除以FACR来推导CCC。我们推荐使用更直接的慢性毒性数据(如繁殖毒性以及多代效应)的结果来推导最终的长期暴露基准。

1.2 受试物种的判别

为了提高水质基准的准确性,用于推导水质基准的数据必须满足一定的生物类群数量的要求,从而能够为不同类群水生生物都提供足够的保护[15]。如1.1所述,繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物由于特殊的MOA以及较大的ACRs,因此不适合用FACR来推导长期暴露基准,而只能利用纯粹的慢性毒性实验结果。当慢性毒性数据量不能满足推导长期暴露基准最少的数据量(如US EPA规定的三门八科)需求时,则需要判别哪些受试生物(或测试终点)比较敏感,而对于不敏感的生物则没有必要测定慢性毒性值。

对于未知作用模式的污染物,判断对哪一类生物类群的敏感性较高需要大量的实验数据来证明和判断。而对于具有特殊作用模式的繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物,我们也可以根据这种方法来判断不同生物对污染物的敏感性[32-33]。US EPA推导水质基准的方法规定利用4个最敏感物种的数据来推导水质基准[30],由于一些不敏感种属的毒性数据对最终的基准结果影响较小,因此只需要足够的敏感物种的毒性数据。以EE2为例,研究证明对于EE2,鱼类相比无脊椎动物更为敏感[28]。因此在考虑EE2水生态基准的推导过程中,鱼类慢性毒性数据对最终的基准值所起的作用至关重要。由于无脊椎动物的毒性数据对最终基准结果影响较小,因而可以减少不必要的实验浪费。同时,当某一污染物的毒性数据不足时,可以用相似作用模式污染物的毒性数据辅助判断生物类群的敏感性差异,比如EE2和E2同作为雌激素类物质对水生生物有着相同的MOA,如果EE2的慢性毒性数据较少时,对于E2敏感的生物类群可以被认定为对EE2也有着相似的结论。

此外,从生物多样性和地理分布差异的角度出发,不同地区的物种敏感度分布也存在差异。因此,许多国家在推导水生态基准时规定使用本土物种的毒性测试数据[30, 34-36]。如US EPA特别规定在制定水生生物基准时不能使用北美地区以外的物种,以免影响到美国基准的正确性。然而,由于繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物针对本土鱼类的慢性数据较少,尤其是一些生命周期较长的鱼类。因此对于一些非本土的国际通用模式鱼类的慢性毒性数据也可以用来推导水生态基准。比如斑马鱼和青鳉鱼,这2种鱼类已经被OECD认定为评价内分泌干扰类化合物的标准受试物种[29]。同时它们也具有非常丰富的毒性数据库。因此,为了保持国际统一性以及协调一致,这类被国际认可的模式物种在推导水生态基准时应该赋予和本土物种相同的权重。

1.3 慢性毒性测试阶段和终点的判别

通常用于推导长期暴露基准的慢性毒性测试包括脊椎动物和无脊椎动物的全生命周期实验(从F0到F1代),以及鱼类的部分生命周期实验(从成鱼到下一代幼鱼)和生命早期阶段实验(从胚胎到幼鱼)。Mckim等[37]研究证实生命早期阶段的实验结果可以被用来作为慢性毒性的实验结果,同时有研究表明可以用生命早期阶段实验结果推算全生命周期的实验结果(通常除以系数2)。然而对于一些特殊的化合物,比如具有繁殖/生殖毒性的EE2,可能更多地会影响生命早期阶段之后性成熟阶段的生殖或者更早的生命阶段(如胚胎性分化和性发育)。这表明对于这一类特殊的化合物不能用生命早期阶段的试验来替代全生命周期的实验。同时,一些研究报道,暴露在很低剂量的内分泌干扰物虽然不会对当代生物产生不良的影响,但是通常会对下一代或者更低代的生物产生影响[38]。如果这种情况比较普遍,这也就意味着即使全生命周期的实验也可能会低估这类化学品的慢性毒性,造成对水生生物保护不足的现象。然而,在目前的条件下我们没有足够的证据要求对在推导水生态基准时一定要使用多代测试实验数据,除非对于某些特别的化合物有足够的信息证明如果不使用多代实验数据会对水生生物保护不足。因此对于常见的繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物在推导水生态基准的过程中,慢性毒性实验需要考虑性成熟阶段对生殖的影响以及早期阶段对胚胎性分化和发育的影响。

制定水质基准的目的是为了“保护水生生物及其用途”,生物的生存、生长和繁殖常被作为评价标准来实现这一保护目标[30]。因为这些效应很容易和群落效应关联起来,所以也常被用来推导水质基准用于保护整个生态系统。然而当生物暴露于毒性污染物,一些生物响应不仅发生在生物个体水平(如行为学),也有可能发生在更低水平的生物组织(如生化和病理学)。而目前对于这些测试终点和保护目标之间的关系尚不清楚。研究证明繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物可能在生物不同的水平产生不同的影响,然而一个重要的挑战是如何建立这些不同水平的响应与生物种群变化之间的关系。针对影响到脊椎动物下丘脑-垂体-性腺轴(HPG轴)的可能的测试终点包括:生化指标(如卵黄蛋白原、雌二醇、睾酮等);组织病理学指标(如精原细胞比例、雌雄兼性的比例等);形态学指标(如第二性征);行为学指标等。这些指标通常被分为2类,一类是指当毒性暴露终止之后对生物个体产生生殖和发育的影响是不可逆的,如性逆转、雌雄兼性等;另一类指暴露终止后个体可能恢复到之前的状态,如行为学、第二性征、卵黄蛋白原等。针对繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物水生态基准推导过程中非常规慢性毒性数据的使用,一个基本的判别原则为是否能够和水生态基准的保护目标以及生物种群的变化有本质的联系(如性别比例的改变)[31]。其他内分泌敏感的指标(如卵黄蛋白原、雌雄兼性)在通过检验之后若等同于生物学意义上重要的测试终点(如繁殖力),比如通过全生命周期试验验证,以及其他具有相同作用模式的化合物(EE2或17β-雌二醇(E2))的毒性结果的验证,可以被用于繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物水生态基准的推导。

2 基于生殖毒性的壬基酚水生态基准推导

壬基酚(nonylphenol, NP)是一种多用途的非离子表面活性剂,是烷基酚类化合物中有代表性的环境污染物,其化学性质稳定、难降解。被广泛应用于农药乳化剂、日用洗涤剂、橡胶塑料的防老剂以及防腐剂等方面。壬基酚在水环境中广泛分布,而且有可能通过生物富集。由于壬基酚在世界上的广泛使用,在日本、美国、德国、韩国等国家的河水与河底淤泥中均有检出[39-41]。同样壬基酚在我国水体环境中的分布范围较广[42-44]。研究表明,壬基酚是一种环境内分泌干扰物,具有类雌激素效应[45-48]。当暴露浓度在5 μg·L-1以上时,即可对稀有鮈鲫的性腺指数、激素含量以及组织水平产生明显的影响[6]。科学家们推测,近年来出现的人类精子数量下降、隐睾和尿道下裂等疾病发生率上升,以及某些水生生物发生性别畸形现象都可能与环境中包括壬基酚在内的某些化学物质对生物体的正常代谢、生殖、发育等功能产生严重干扰有关[49]。因此对这一污染物产生的危害效应识别以及其存在的生态风险管理引起了人们广泛的关注和重视[50]。我国目前尚没有壬基酚的水质标准。

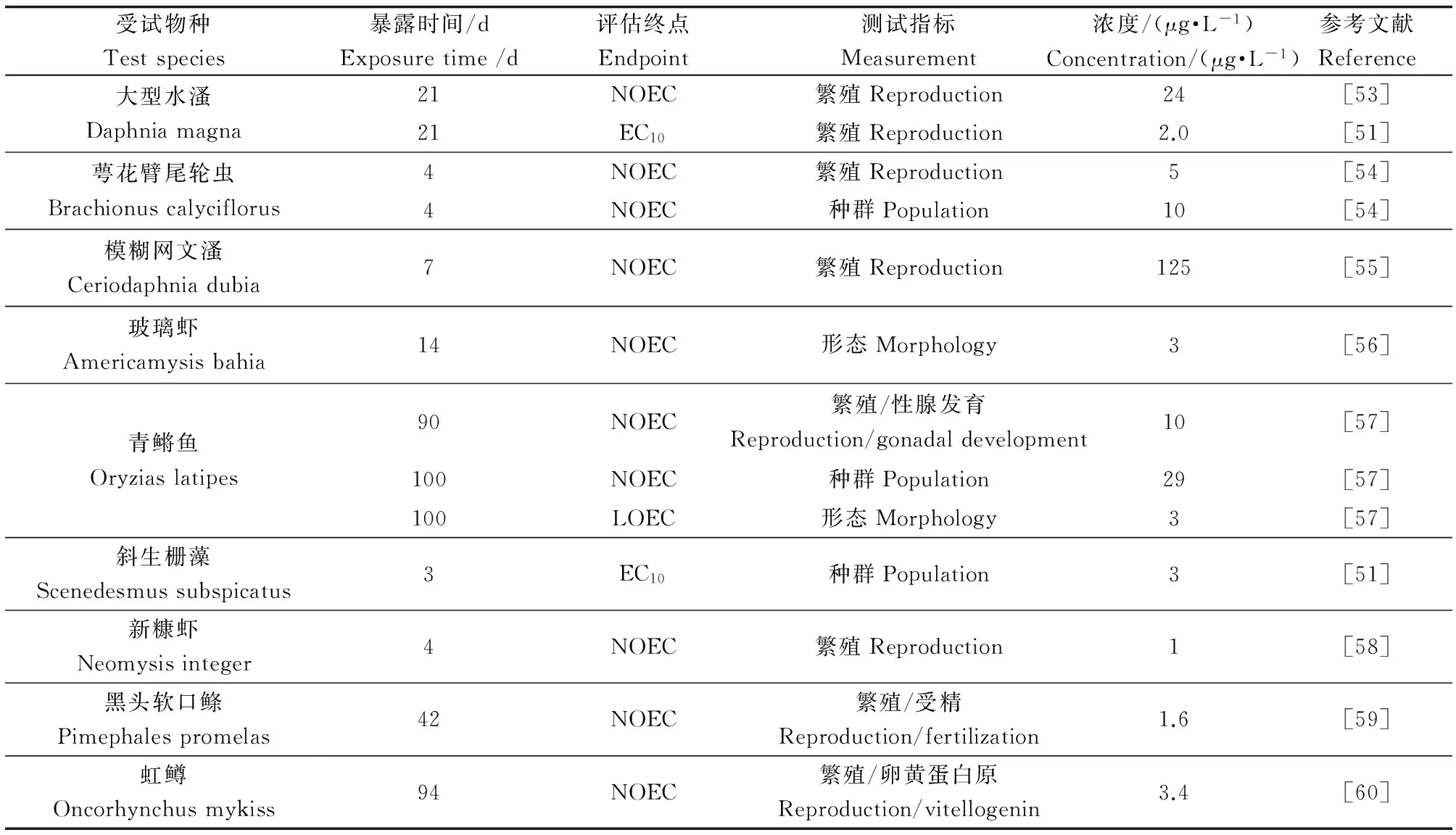

针对繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物的特殊性,直接筛选慢性毒性数据推导壬基酚的长期暴露基准。壬基酚对淡水水生生物的毒性数据主要来自于现有的毒性数据库(例如,ECOTOX数据库http://cfpub.epa.gov/ecotox/)[51],以及已发表的文献等。受试生物以鱼类的繁殖毒性以及种群变化的数据为主,其他生物类群的生物的生殖毒性数据作为补充。基于生殖毒性的测试终点包括生殖力、受精率、孵化率、性腺指数以及多代效应等。慢性毒性数据评价终点为无观察效应浓度(no observed effect concentration, NOEC),当未搜索到NOEC值时,可用最大可接受浓度(maximum acceptable toxic concentration, MATC),最低可观察效应浓度(lowest observed effect concentration, LOEC)或ECx来替代,并在数据中标注(表1)。毒性数据筛选一般遵循3个原则:精确性、适当性、可靠性[18,52]。

表1 壬基酚对不同类群水生生物的繁殖毒性结果

注:NOEC为无观察效应浓度;LOEC为最低可观察效应浓度;EC10为10%效应浓度。

Note: NOEC stands for no observed effect concentration; LOEC stands for lowest observed effect concentration; EC10stands for effective concentration at 10%.

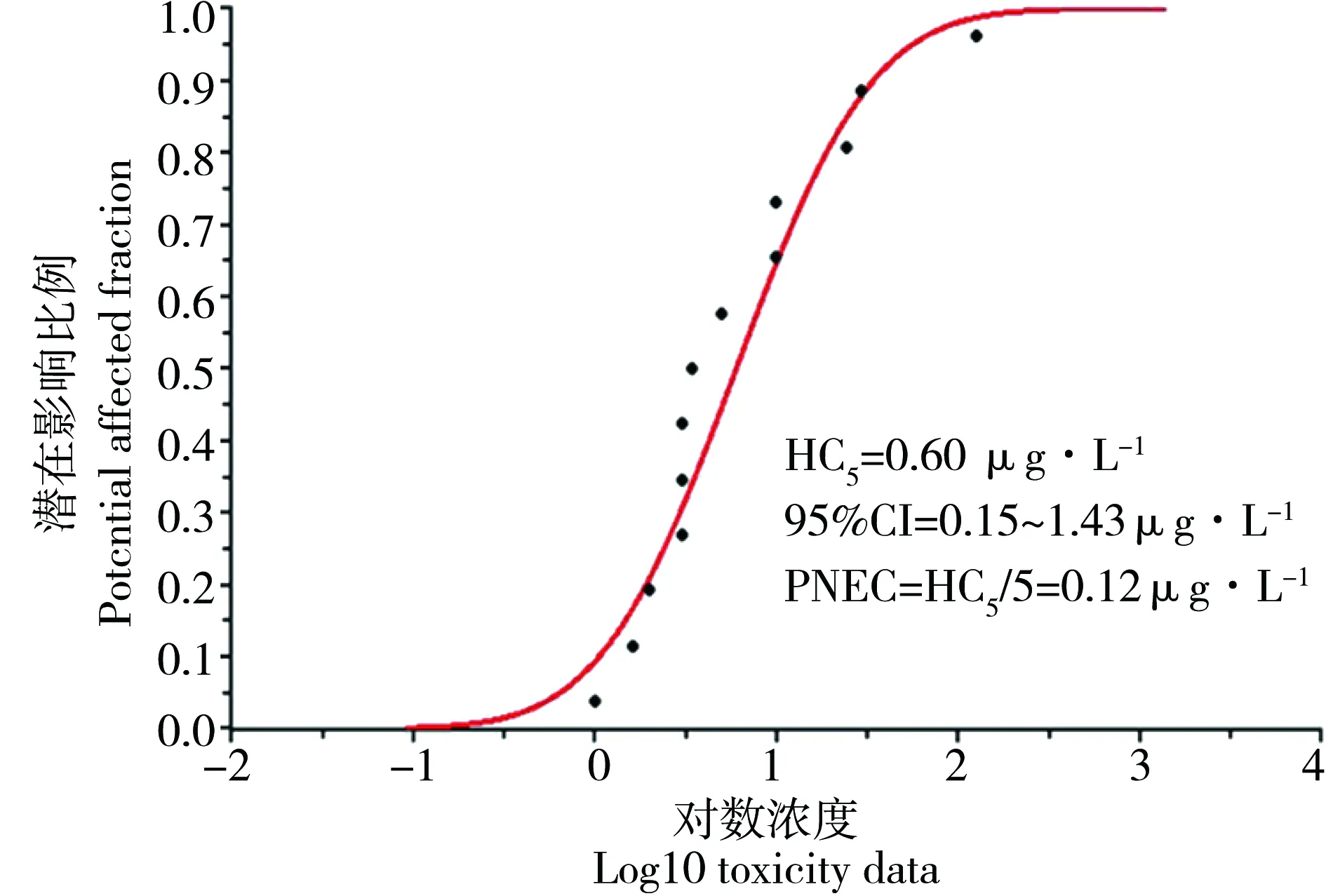

物种敏感度分布曲线法(SSDs)常被用于生态风险评估中的效应评估,即使用累计概率分布拟合SSD曲线来表述对某一特定生物群体不引起不良效应的最高浓度[15, 36, 61]。通常使用HC5来表示至少能够保护95%以上物种的浓度值。本文采用荷兰开发的ETX 2.0, RIVM程序计算50%置信度的HC5值[62],最后将50%置信度的HC5值除以5分别计算得出壬基酚的PNEC值[63]。

图1 基于繁殖毒性结果的壬基酚物种敏感度曲线分布Fig. 1 Species sensitivity distribution of nonylphenol based on reproductive toxicity data

依据毒性数据筛选原则,共整理到14个壬基酚对水生生物的繁殖毒性(包括产卵量、受精率、孵化率、多代效应以及种群变化等)结果,其中包括5种鱼类,8种无脊椎动物和1种浮游藻类,其NOEC(ECx)值的范围为1.0~125 μg·L-1,均值为21.24 μg·L-1。用ETX 2.0、RIVM程序计算50%置信度的HC5值0.60(95% CI 0.15~1.43) μg·L-1。从而得出基于生殖毒性的壬基酚PNEC值为0.12 μg·L-1。这一结果比US EPA推导的CCC(6.59 μg·L-1)低了近50倍[19]。欧盟关于壬基酚的生态风险评估中基于鱼类的内分泌干扰数据推导出壬基酚的PNECs值为0.33 μg·L-1[64],Lin等[65]研究结果显示壬基酚对青鳉鱼种群变化不产生明显效应的NOECs值范围为0.82~2.10 μg·L-1。本研究推导得出的PNEC值基本与基于鱼类内分泌干扰数据推导得出的安全阈值在同一数量级,但是在数字上略小。这种差异可能是由于不同地理区域物种分布以及不同生物类群物种敏感性的差异造成。由此可见,根据壬基酚生殖毒性结果推导的PNEC值0.12 μg·L-1作为壬基酚的水生态基准值,适用于避免水生生物可能受到的生殖繁殖损伤。基于本研究中关于壬基酚水生态基准的推导与Caldwell等[18]基于生殖效应对17α-乙炔雌二醇(EE2)PNEC值的研究,我们认为针对繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物,基于其繁殖毒性(包括产卵量、受精率、孵化率、多代效应以及种群变化等)的实验结果更适合用于具有繁殖/生殖毒性污染物水生态基准的推导[50]。

[1] 包国章, 董德明, 李向林. 环境雌激素生态影响的研究进展[J]. 生态学杂志, 2001, 20(5): 44-50

Bao G Z, Dong D M, Li X L, et al. Progress of studies on ecological effects of ecoestrogen [J]. Chinese Journal of Ecology, 2001, 20(5): 44-50 (in Chinese)

[2] Bennetts H, Uuderwood E, Shier F. A specific breeding problem of sheep on subterranean clover pastures in Western Australia [J]. Australian Veterinary Journal, 1946, 22(1): 2-12

[3] Semenza J C, Tolbert P E, Rubin C H, et al. Reproductive toxins and alligator abnormalities at Lake Apopka, Florida [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 1997, 105(10): 1030-1032

[4] Hennies M, Wiesmann M, Allner B, et al. Vitellogenin in carp (Cyprinus carpio) and perch (Perca fluviatilis): Purification, characterization and development of an ELISA for the detection of estrogenic effects [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2003, 309(1): 93-103

[5] Crane M, Watts C, Boucard T. Chronic aquatic environmental risks from exposure to human pharmaceuticals [J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2006, 367(1): 23-41

[6] Zha J, Wang Z, Wang N, et al. Histological alternation and vitellogenin induction in adult rare minnow (Gobiocypris rarus) after exposure to ethynylestradiol and nonylphenol [J]. Chemosphere, 2007, 66(3): 488-495

[7] Zha J, Sun L, Spear P A, et al. Comparison of ethinylestradiol and nonylphenol effects on reproduction of Chinese rare minnows (Gobiocypris rarus) [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2008, 71(2): 390-399

[8] Kim Y, Choi K, Jung J, et al. Aquatic toxicity of acetaminophen, carbamazepine, cimetidine, diltiazem and six major sulfonamides, and their potential ecological risks in Korea [J]. Environment International, 2007, 33(3): 370-375

[9] Gooding M, Newton T, Bartsch M, et al. Toxicity of synthetic musks to early life stages of the freshwater mussel Lampsilis cardium [J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2006, 51(4): 549-558

[10] Nakata H. Occurrence of synthetic musk fragrances in marine mammals and sharks from Japanese coastal waters [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2005, 39(10): 3430-3434

[11] Sun L, Zha J, Spear P A, et al. Toxicity of the aromatase inhibitor letrozole to Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) eggs, larvae and breeding adults [J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology, 2007, 145(4): 533-541

[12] Zha J, Sun L, Zhou Y, et al. Assessment of 17α-ethinylestradiol effects and underlying mechanisms in a continuous, multi-generation exposure of the Chinese rare minnow (Gobiocypris rarus) [J]. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2008, 226: 298-308

[13] Cunningham V L, Buzby M, Hutchinson T, et al. Effects of human pharmaceuticals on aquatic life: Next steps [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2006, 40(11): 3456-3462

[14] 金小伟, 雷炳莉, 许宜平, 等. 水生态基准方法学概述及建立我国水生态基准的探讨[J]. 生态毒理学报, 2009, 4(5): 609-616

Jin X W, Lei B L, Xu Y P, et al. Methodologies for deriving water quality criteria to protect aquatic life (ALC) and proposal for development of ALC in China: A review [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2009, 4(5): 609-616 (in Chinese)

[15] 金小伟, 王业耀, 王子健. 淡水水生态基准方法学研究: 数据筛选与模型计算[J]. 生态毒理学报, 2014, 9(1): 1-13

Jin X W, Wang Y Y, Wang Z J. Methodologies for deriving aquatic life criteria (ALC): Data screening and model calculating [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2014, 9(1): 1-13 (in Chinese)

[16] 雷炳莉, 金小伟, 黄圣彪, 等. 太湖流域三种氯酚类化合物水质基准的探讨[J]. 生态毒理学报, 2009, 4(1): 40-49

Lei B L, Jin X W, Huang S B, et al. Discussion of quality criteria for three chlorophenols in Taihu Lake [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2009, 4(1): 40-49 (in Chinese)

[17] 吴丰昌, 孟伟, 宋永会, 等. 中国湖泊水环境基准的研究进展[J]. 环境科学学报, 2008, 28(12): 2385-2393

Wu F C, Meng W, Song Y H, et al. Research progress in lake water quality criteria in China [J]. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae, 2008, 28(12): 2385-2393 (in Chinese)

[18] Caldwell D J, Mastrocco F, Hutchinson T H, et al. Derivation of an aquatic predicted no-effect concentration for the synthetic hormone, 17 alpha-ethinyl estradiol [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2008, 42(19): 7046-7054

[19] US EPA. National Recommended Water Quality Criteria, United States Environmental Protection Agency [S]. Washington DC: US EPA, 2006

[20] Ackermann G E, Schwaiger J, Negele R D, et al. Effects of long-term nonylphenol exposure on gonadal development and biomarkers of estrogenicity in juvenile rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2002, 60(3): 203-221

[21] Besser J M, Wang N, Dwyer F J, et al. Assessing contaminant sensitivity of endangered and threatened aquatic species: Part II. Chronic toxicity of copper and pentachlorophenol to two endangered species and two surrogate species [J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2005, 48(2): 155-165

[22] Brix K V, Deforest D K, Adams W J. Assessing acute and chronic copper risks to freshwater aquatic life using species sensitivity distributions for different taxonomic groups [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2001, 20(8): 1846-1856.

[23] 史熊杰, 刘春生, 余珂, 等. 环境内分泌干扰物毒理学研究[J]. 化学进展, 2009, 21(2/3): 340-349

Shi X J, Liu C S, Yu K, et al. Toxicological research on environmental endocrine disruptors [J]. Progress In Chemistry, 2009, 21(2/3): 340-349 (in Chinese)

[24] Webb S. A Data Based Perspective on the Environmental Risk Assessment of Human Pharmaceuticals II-Aquatic Risk Characterisation [M]// Pharmaceuticals in the Environment, Berlin: Springer Heidelberg, 2001: 203-219

[25] Webb S. A Data-Based Perspective on the Environmental Risk Assessment of Human Pharmaceuticals I-Collation of Available Ecotoxicity Data [M]// Pharmaceuticals in the Environment, Berlin: Springer Heidelberg, 2004: 317-343

[26] Host G, Regal R, Stephan C. Analyses of acute and chronic data for aquatic life. PB93-154748 US EPA Report. [R]. Duluth, MN: US EPA, 1991

[27] Ankley G, Black M, Garric J, et al. A Framework for Assessing the Hazard of Pharmaceutical Materials to Aquatic Species [M]// Human Pharmaceuticals: Assessing the Impacts on Aquatic Ecosystems, 2005: 183-238

[28] Segner H, Navas J, SchäFers C, et al. Potencies of estrogenic compounds in in vitro screening assays and in life cycle tests with zebrafish in vivo [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2003, 54(3): 315-322

[29] Ankley G T, Johnson R D. Small fish models for identifying and assessing the effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals [J]. Ilar Journal, 2004, 45(4): 469-483

[30] US EPA. Guidelines for Deriving Numerical National Water Quality Criteria for the Protection of Aquatic Organisms and Their Uses. National Technical Information Service Accession Number PB85-227049 [S]. Washington DC: US EPA, 1985

[31] US EPA. OW/ORD Emerging Contaminants Workgroup. Aquatic Life Criteria for contaminants of emerging concern, Part I, general challenges and recommendations [R]. Washington DC: US EPA, 2008

[32] Ankley G T, Brooks B W, Huggett D B, et al. Repeating history: Pharmaceuticals in the environment [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2007, 41(24): 8211-8217

[33] Williams R T. Human Pharmaceuticals: Assessing the Impacts on Aquatic Ecosystems [M]. Pensacola, FL: Allen Press/ACG Publishing, 2005: 183-237

[34] Hose G C, Van Den Brink P J. Confirming the species-sensitivity distribution concept for endosulfan using laboratory, mesocosm, and field data [J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2004, 47(4): 511-520

[35] Jin X, Zha J, Xu Y, et al. Derivation of predicted no effect concentrations (PNEC) for 2,4,6-trichlorophenol based on Chinese resident species [J]. Chemosphere, 2012, 86: 17-23

[36] Jin X W, Zha J M, Xu Y P, et al. Derivation of aquatic predicted no-effect concentration (PNEC) for 2,4-dichlorophenol: Comparing native species data with non-native species data [J]. Chemosphere, 2011, 84(10): 1506-1511

[37] Mckim J, Eaton J, Holcombe G W. Metal toxicity to embryos and larvae of eight species of freshwater fish-II: Copper [J]. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 1978, 19(1): 608-616

[38] Nash J P, Kime D E, Van Der Ven L T, et al. Long-term exposure to environmental concentrations of the pharmaceutical ethynylestradiol causes reproductive failure in fish [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2004, 112(17): 1725-1733

[39] Fawell J, Sheahan D, James H, et al. Oestrogens and oestrogenic activity in raw and treated water in severn trent water [J]. Water Reseach, 2001, 35(5): 1240-1244

[40] Kannan K, Keith T, Naylor C, et al. Nonylphenol and nonylphenol ethoxylates in fish, sediment, and water from the Kalamazoo River, Michigan [J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2003, 44(1): 77-82

[41] Ying G G, Williams B, Kookana R. Environmental fate of alkylphenols and alkylphenol ethoxylates-A review [J]. Environment International, 2002, 28(3): 215-226

[42] Jiang W, Yan Y, Ma M, et al. Assessment of source water contamination by estrogenic disrupting compounds in China [J]. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2012, 24(2): 320-328

[43] Shao B, Hu J, Yang M, et al. Nonylphenol and nonylphenol ethoxylates in river water, drinking water, and fish tissues in the area of Chongqing, China [J]. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 2005, 48(4): 467-473

[44] Xu J, Wang P, Guo W, et al. Seasonal and spatial distribution of nonylphenol in Lanzhou Reach of Yellow River in China [J]. Chemosphere, 2006, 65(9): 1445-1551

[45] Bandiera S M. Reproductive and endocrine effects of p-nonylphenol and methoxychlor: A review [J]. Immunology, Endocrine & Metabolic Agents-Medicinal Chemistry, 2006, 6(1): 15-26

[46] Giesy J P, Pierens S L, Snyder E M, et al. Effects of 4‐nonylphenol on fecundity and biomarkers of estrogenicity in fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas) [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2000, 19(5): 1368-1377

[47] Nimrod A C, Benson W H. Environmental estrogenic effects of alkylphenol ethoxylates [J]. CRC Critical Reviews in Toxicology, 1996, 26(3): 335-364

[48] Lei B, Wen Y, Wang X, et al. Effects of estrone on the early life stages and expression of vitellogenin and estrogen receptor genes of Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) [J]. Chemosphere, 2013, 93(6): 1104-1110.

[49] 范奇元, 金泰, 将学之, 等. 我国部分地区环境中壬基酚的检测[J]. 中国公共卫生, 2002, 18(11): 1372-1373

[50] Jin X, Wang Y, Jin W, et al. Ecological risk of nonylphenol in China surface waters based on reproductive fitness [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2014, 48(2): 1256-1262

[51] US EPA. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, ECOTOX Database [DB]. [2014-02-10]. http://cfpub.epa.gov/ecotox/

[52] Klimisch H J, Andreae M, Tillmann U. A systematic approach for evaluating the quality of experimental toxicological and ecotoxicological data [J]. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, 1997, 25(1): 1-5

[53] Comber M, Williams T, Stewart K. The effects of nonylphenol on Daphnia magna [J]. Water Reseach, 1993, 27(2): 273-276

[54] Preston B L, Snell T W, Robertson T L, et al. Use of freshwater rotifer Brachionus calyciflorus in screening assay for potential endocrine disruptors [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2000, 19(12): 2923-2928

[55] Tatarazako N, Takao Y, Kishi K, et al. Styrene dimers and trimers affect reproduction of daphnid (Ceriodaphnia dubia) [J]. Chemosphere, 2002, 48(6): 597-601

[56] Hirano M, Ishibashi H, Kim J W, et al. Effects of environmentally relevant concentrations of nonylphenol on growth and 20-hydroxyecdysone levels in mysid crustacean, Americamysis bahia [J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology, 2009, 149(3): 368-373

[57] Balch G, Metcalfe C. Developmental effects in Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) exposed to nonylphenol ethoxylates and their degradation products [J]. Chemosphere, 2006, 62(8): 1214-1223

[58] Verslycke T, Poelmans S, De Wasch K, et al. Testosterone and energy metabolism in the estuarine mysid Neomysis integer (Crustacea: Mysidacea) following exposure to endocrine disruptors [J]. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2004, 23(5): 1289-1296

[59] Brooke L. Acute and chronic toxicity of nonylphenol to ten species of aquatic organisms [R]. Washionton DC: US EPA, 1993

[60] Schwaiger J, Mallow U, Ferling H, et al. How estrogenic is nonylphenol: A transgenerational study using rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) as a test organism [J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2002, 59(3): 177-189

[61] Wheeler J R, Grist E P M, Leung K M Y, et al. Species sensitivity distributions: Data and model choice [J]. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2002, 45(1-12): 192-202

[62] Aldenberg T, Jaworska J S. Uncertainty of the hazardous concentration and fraction affected for normal species sensitivity distributions [J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2000, 46(1): 1-18

[63] ECB. Technical guidance document on risk assessment in support of commission directive 93/67/EEC on risk assessment for new notified substances, commission regulation (EC) no. 1488/94 on risk assessment for existing sunstances, derective 98/8/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning the placing of biocidal products on the market. Part II. Environmental Risk Assessment. [R]. European Chemicals Bureau, European Commission Joint Research Center, European Communities, 2003

[64] EC. European Union Risk-Assessment Report Vol.10, 2002 on 4-nonylphenol (branched) and nonylphenol [R]. Ispra, Italy: European Chemicals Bureau, Joint Research Centre, European Commission, 2002

[65] Lin B L, Tokai A, Nakanishi J. Approaches for establishing predicted-no-effect concentrations for population-level ecological risk assessment in the context of chemical substances management [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2005, 39(13): 4833-4840

◆

Methodologies for Deriving Aquatic Life Criteria (ALC): Discussion of ACL for Chemicals Causing Reproductive Toxicity

Jin Xiaowei1, Wang Zijian2,*, Wang Yeyao1, Liu Na3

1. China National Environmental Monitoring Center, Beijing100012, China 2. Research Center for Eco-Environmental Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100085, China 3. China University of Geosciences(Beijing), Beijing, 100083

4 April 2014 accepted 20 May 2014

Chemicals causing reproductive toxicity (CCRT) can cause the change of the population and community by affecting biological reproduction due to its specific toxicological mode of action (MOA). It has been recognized that aquatic life criteria based on traditional acute and chronic endpoints of toxicity are unable to provide adequate protection because some chemicals may affect reproductive fitness of aquatic organisms at much lower concentrations. This review was undertaken to identify key outstanding issues of ALC deriving for CCRT, including the need for and relevance of acute toxicity data and a criteria maximum concentration (CMC), defining minimum data requirements in terms of taxonomic coverage, defining appropriate chronic toxicity data and effect endpoints. In addition, a predicted no effect concentration (PNEC) of 0.12 μg·L-1were derived for nonylphenol (NP) based on literature reproduction data. This result is lesser by a factor of 50 than the criteria continuous concentration(CCC) of 6.59 μg·L-1derived by use of acute to chronic ratios (ACRs) recommended by US EPA. Therefore, toxicity data based on their reproductive toxicity (including fecundity, fertility, hatchability, multi-generational effects and changes in the population, and etc.) is more suitable for ALC deriving for CCRT.

nonyl phenol; endocrine disrupter; freshwater organisms; reproductive toxicity; water quality criteria

国家自然科学青年基金(21307165);环境模拟与污染控制国家重点联合实验室(中国科学院生态环境研究中心)开放基金(14K02ESPCR)

金小伟(1985-),男,博士,工程师,研究方向为水质基准与标准以及区域生态风险评价,E-mail: jxw85@126.com;

*通讯作者(Corresponding author),E-mail: wangzj@rcees.ac.cn

10.7524/AJE.1673-5897.20140404001

2014-04-04 录用日期:2014-05-20

1673-5897(2015)1-031-09

X171.5

A

王子健(1953—),男,研究员,博士生导师,主要研究天然水体和水处理过程中的水质转化、相关毒性和毒理变化以及健康和生态风险。

金小伟, 王子健, 王业耀, 等. 淡水水生态基准方法学研究:繁殖/生殖毒性类化合物水生态基准探讨[J]. 生态毒理学报, 2015, 10(1): 31-39

Jin X W, Wang Z J, Wang Y Y, et al. Methodologies for deriving aquatic life criteria (ALC): Discussion of ACL for chemicals causing reproductive toxicity [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2015, 10(1): 31-39 (in Chinese)