封面故事

BY DAVID DAWSON

封面故事

COVER STORY

BY DAVID DAWSON

How Communist China became a cradle for innovative startups an d the plucky tech entre preneurs that call it home

在电子科技的带领下,一场创业风暴正在席卷中国

Whittled down from around 30 over the course of a weekend at Microsoft’s China R&D of fi ces in Beijing’s bustling tech district Zhongguancun (中关村), six hopeful Chinese tech startups remained in the running. Would the victor be the minds behind a personalized fi tness app or those who developed a platform for private equity transactions? Perhaps the creators of a journey planner complete with suggestions based on users’ hobbies?

They were competing for a guaranteed 50,000 RMB in seed money, but perhaps more tantalizing were the potential contacts that could be forged with representatives of the venture capital groups scrutinizing them. In the end, the March 2015 event concluded when a novelty check was handed to the creators of an app that hopes to replace employee workshops with an app that trains staff in operating procedures and measures milestones. The scene was one that would have been alien to the Chinese mainland of a few decades ago, when the idea of Chinese venture capital funds on the prowl was just as outlandish a concept as the yet-to-be-invented smartphone.

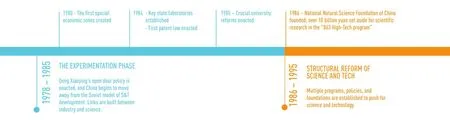

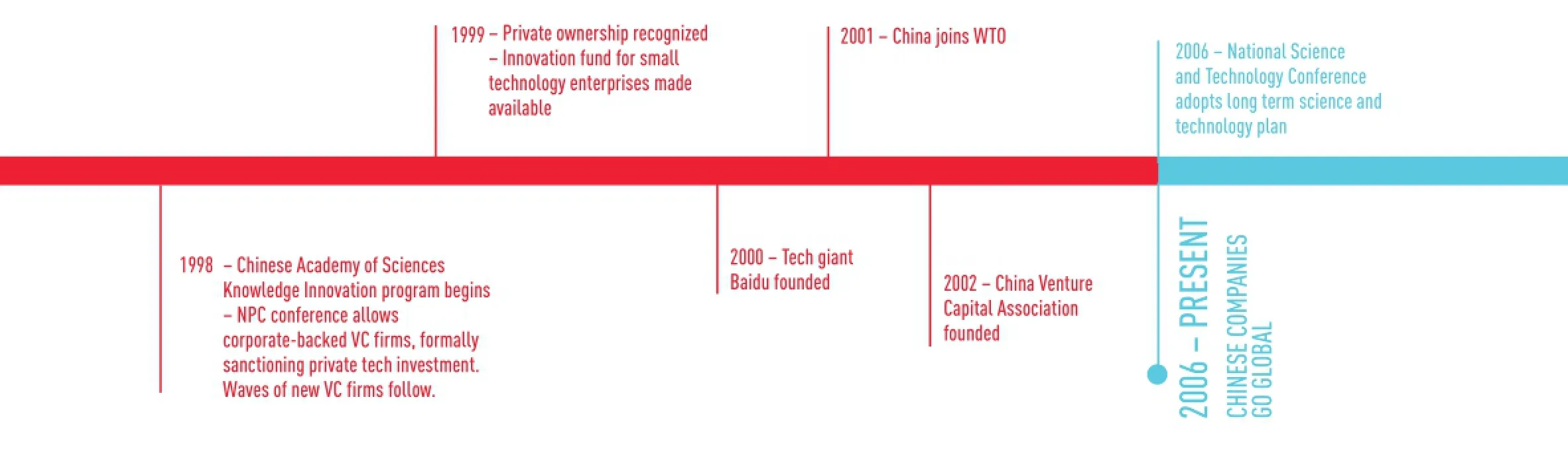

But times have certainly changed. In 2015, of all the global technology companies worldwide with a market value of over a billion, the 50 top performers all came from China, Bloomberg reported in April. The pace and scale of this change in the Middle Kingdom is nowhere more apparent than Zhongguancun, the fi rst successful creation from the Ministry of Science and Technology’s “Torch” program (火炬计划) in 1988.

While in many ways it still resembles the electronics markets of the 80s, jostling with patrons out to buy bargain-basement laptops, Zhongguancun today is in many ways the brainchild of Chen Chunxian (陈春先), a Sichuan physicist, who in the 1970s led a team of scientists to create China’s fi rst tokamak reactor—a device fi rst devised by Russian scientists in the 1950s to create and contain thermonuclear fusion power.

But it was Chen’s trip to Silicon Valley in the early 1980s that would lay the seeds for Zhongguancun. He returned with ideas regarding areas with a concentration of talent and technology, which would form the basis for the fi rst and most successful of China’s innovation clusters.

As with the tokamak reactor, Chen both copied and innovated to create something that would work for China. Crucially for startups, these clusters had incubators for tech businesses, which offered free rent and connections with universities and government departments. A startup that was part of the Torch program also, crucially, had the green light from banks to receive loans.

Thus, somewhat ironically, startups—arguably the most cutting edge form of capitalism–in China arose from centrally-planned industry zones, an idea that sits quite comfortably with communism. Since then, China has developed something of an addiction to industry zones, creating tens of thousands of them throughout the country.

While at fi rst this may seem entirely at odds with the entrepreneurial spirit of Silicon Valley, in reality the difference isn’t quite so pronounced. Andy Mok, the organizer of the Beijing Tech Hive and a partner at Songyuan Capital—the venture capital group that fronted the 50,000 RMB—points out that although China is often in the headlines for supporting tech businesses, Silicon Valley did not emerge from a vacuum.

Although many of the plucky, fi ercely independent entrepreneurs who lead US startups today tend to play down the impact of government investment, in its early days, government funding in the form of defense spending poured into Silicon Valley, with the fi rst government contract being awarded to Stanford researchers led by Frederick Terman in 1946.

If Chen is responsible for Zhongguancun, then Terman, along with William Shockley, who helped create and commercialize the transistor, are responsible for Silicon Valley. Terman encouraged his students to set up fi rms in the area, including the founders of Hewlett Packard. Later Stanfordwould lease areas to startup fi rms which included Lockheed Martin, today a bene fi ciary of extensive government largesse and one of the largest employers in Silicon Valley, in a pattern somewhat similar to that which characterizes Zhongguancun today.

One would think that with its proximity to China’s best universities, startups residing in Zhongguancun and greater Beijing would have no problem fi nding talent, but for Mok—also a former Rand corporation researcher who analyzed Chinese tech—it is perhaps the most signi fi cant challenge.

“Silicon Valley is a magnet for people with the right expertise,” Mok points out. “Beijing has Tsinghua, Beida, and Beihang [universities]. The quality of education is not as high, but this is changing.” Mok also recruits talent for placement in Chinese startups, and says he sees immense potential for their growth in the future. He points to the massive growth in smartphones and tech consumers in locations like Southeast Asia and India and says, “Chinese companies are better situated to take advantage of these markets.”

“I think as a developing country, China understands these markets more,” he says, drawing parallels between the experiences of consumers in both. Mok says as a rule of thumb (stressing that it’s a very loose rule of thumb) that it takes around fi ve million USD in capital to launch a startup in the US, whereas it is around 500,000 USD in China. They also require a culture where participants are able to make mistakes and learn from them, something which in the past was dif fi cult in China’s risk-averse corporate environment.

“A successful startup really is about making mistakes, learning and adapting,” Mok points out, saying that the best ones “make their mistakes quickly”. He adds that even in cases where it appears from the outside that a startup has been an immediate success, there are usually more subtle forms of failure that shaped the experiences of the founders.

But as with all industries, the Chinese tech sector has both its bulls and its bears.

The bears point toward the massive growth in the Chinese tech sector, and draw parallels with the dot-com bubble. With the industry at the forefront of China’s stock market, and valuations now at an average of 220 times reported pro fi ts, the discrepancy is far above the earnings versus price ratio of 1:156 that characterized the US dot-com bubble of the late 1990s and 2000.

A number of experts are warning of a Chinese bubble that would be more abrupt, albeit have less fallout than the US bubble due to the more limited role tech stocks play in the Chinese equity market. But in the meantime, scrappy startups continue to emerge, hoping to make a place among China’s tech billionaires.

RED TAPE

Starting a business isn’t easy, but the process has become vastly simplified in recent years. One anonymous web entrepreneur revealed the process behind starting one of the easiest kinds of businesses—a simple website offering shopping advice. First up, the business will need a name. This requires an application with the Bureau of Industry and Commerce as well as the State Administration of Tax. Both departments will use the one application, but you will be shuttled from one to the other at some point. If the name is free, congratulations, you’re on the 20-working-day waiting list for approval. There is also a two-week period when the website is being recorded, though this can happen in conjunction with the other process. In many cases, aspiring entrepreneurs ask agencies, with more experience and possibly connections, to handle these matters on their behalf. In total, the process will cost around 2,000 RMB for a business in Beijing, and around 1,000 RMB in Shanghai. Then you need an actual business license. For registering a website that offers shopping advice, it’s relatively easy. Same goes for certain online businesses, such as website design or advertising. So best case scenario, you are up and running after about a month. But if you want to go into something like banking, insurance or medicine, be prepared for a grueling wait, as the requirements for establishing these businesses are notoriously bureaucratic and involve multiple government departments. Once the business is up and running, monthly financial reports must be filed with the tax bureau. But as the business grows, so too does the red tape.

FINDING A NICHE

Whether it’s China’s Google-equivalent Baidu, bargain smartphone manufacturer Xiaomi, or online payment system Alipay, China has no shortage of tech giants of its own, though one thread they all share is that they used the unique circumstances of the Chinese market to carve out their niche. This allowed them to prosper in China’s very different market but has posed challenges when large companies seek to spread their wings on the global stage.

Nevertheless, for startups it is that unique Chinese niche that de fi nes whether they will fail or succeed. Take Tuanche for example. Going from around a dozen employees in 2009 to over 700 now, Tuanche is among the leaders in its niche. The website offers advice on buying cars andmakes arrangements with car dealers to sell in bulk to large groups of customers, thus obtaining lower prices for clients.

The sheer size of the Chinese market—combined with the relative ignorance of many consumers when it comes to purchasing cars, due in no small part to fi rst-time buyers in a rapidly growing marketplace—created this niche for the “group buying” of cars.

CEO Wen Wei says that success wasn’t easy. Echoing Mok’s comments about the importance of failure, Wen said he previously operated several startups and learned from his mistakes. The most crucial lesson was having the right people on board at the beginning. “We started out as a group of salespeople. But over time we had to bring in developers.”

“Many Chinese buyers are not well-educated when it comes to buying cars. We were able to forge links with car dealers, and by buying in bulk, we were able to leverage better deals for our customers,” Wen says.

As has been the case with most successful startups in China, copycats seeking to make a fast buck immediately swarmed, and to stay ahead of the pack, Wen says that the company has had to ensure it stays focused on its customers and keep long term goals in mind rather than jumping at immediate opportunities.

Other startups fi nd industry-speci fi c problems and seek to remedy them. Previous tech-hive winner Apricot Forest targeted the medical industry, in which underpaid doctors fi nd themselves under extreme pressure from both hospitals and angry patients. A survey by the China Hospital Association found an average of 27 assaults on doctors per hospital each year. Long waiting times and overloaded doctors combined with a culture of bribery and poor wages created a situation in which any tool that saves time is of immense use.

This was where Apricot Forest entered the equation, providing a collection of services via an app. The app allows doctors to record all patient records and can facilitate communication with patients via China’s immensely popular WeChat messaging platform. It also allows the doctors to liaise with peers on diagnoses and check the latest medical journals.

Adaptation is another key component. Wei Rongjie, one of the founders of fl edgling company Caputer Labs, initially began working on lenses to magnify smartphone screens to make the experience of watching movies on them more pleasant. Many young Chinese rely on smartphones for multimedia viewing, as many may not have easy access to other equipment to watch movies.

With inspiration coming from the success of the Oculus Rift headset, the idea evolved, eventually becoming the Seer headset, an open-source Augmented Reality developer kit. The Caputer Labs team recently exceeded a Kickstarter goal of 100,000 USD, bringing in over 160,000 USD.

Business lead Baicheng Hou said that because augmented reality is a new fi eld, the time-window for development is quite limited. “We have had to speedup our research and development. It is crucial for us to plan and improve our product so it can survive in the market.”

Of course, once enough money becomes involved, survival becomes not just about business nous but politics as well. Take for example the case of Li Jingwei—in 1984 he took over soft drink maker Jianlibao, a state-owned company under the Sanshui government in Guangdong Province.

In the 90s the company hit its peak, with fi ve billion RMB in annual revenue, and the Jianlibao soft drink had become an iconic brand for many young Chinese. But this then raised the question—to what extent could Li try to exert ownership?

Things came to a head when Li offered a 450 million RMB buyout of the company and attempted to move it out of the province. Instead the government hurriedly sold the company to another state-owned company, and Li was noti fi ed just a few days before the signing ceremony, according a report in Forbes, which said that he was in tears. Within days he suffered a brain hemorrhage.

He was charged with embezzlement of public funds in 2002, and died in 2013. The company had been through a tumultuous period, with high debt and accusations of mismanagement.

FINANCIAL FRONTIERS

The truism is as valid in China as in the West: startups can’t survive without capital. But capital in China is subject to an entirely different set of rules, which change year to year. Although the strict barriers to obtaining loans from China’s banking behemoths (four of the world’s ten biggest banks are Chinese) are being worn away, it remains almost impossible for plucky startups to obtain a bank loan. High requirements for deposits and curbs aimed at controlling the often turbulent property market make it dif fi cult for smaller players to access any kind of loan, whether for a startup or simply to buy property.

With banks out of the picture, connections to government funding can help, with it often coming through universities, incubators, innovation funds, or R&D think tanks. On the private side of the equation, a wide array of fi nancial options—often entirely above board, but occasionally very shady—have emerged as alternatives for those seeking to pro fi t from the country’s booming economy. Collectively they are referred to as shadow banking.

As was the case in ancient China, the most common way of obtaining money for an investment is to tap friend and family networks. In these cases, someone buying an apartment or launching a business fi rst turns to family, then friends, then connections. Most of the time, they are unremarkable, particularly when the loan pays off—which is generally a safe bet when property is involved, given the consistently increasing land prices.

But there are darker tales as well. At the village level, these networks of connections have been known to coalesce into lending empires, which then metastasize into entire counties becoming fi nancial hubs. As the interest rates soar and businesses collapse, these lending sprees occasionally implode with catastrophically violent results.

In one of the most high pro fi le cases, in April of

2012, The Jinan Times reported on a hit and run caraccident which claimed the life of two men. One of them, Zhu Bao, called his family at midnight asking for help, as he and his cousin were being pursued by three cars carrying a dozen people. Their car crashed into a truck and both men died at the scene. The pair had reportedly been targeted by loan sharks after a four million RMB deal went bad.

PURSUIT OF PROFIT

A HANDFUL OF STARTUPS TO WATCH IN 2015

· Microloans for college kids who need an iPhone by Aixuedai (爱学贷)

· Universal power adapters by Kankun Technology (坎坤科技)

· An app called Hao Chushi (好厨师) lets you hire a chef for the night

· Milk Nanny, a milk powder mixer birthed on Kickstarter

· AutoBot (车车智能) app lets you track your car’s analytics

· Tingchebao (停车宝) parking app that finds you a spot

· Virtual—reality—equipped drone from ElecFreaks

The media followed the trail to the textile hub of Zouping County in the middle of Shandong Province. In this area of 13 towns and hundreds of villages which houses roughly 950,000 people, reporters discovered that thousands of ordinary citizens had rushed to become lenders, but residents told the Jinan Times many had been killed over debts. Loans had been given out with rates far higher than those demanded by banks, which then became loans to others at even higher rates. Attracted by the scent of pro fi t, lenders from China’s entrepreneurial hub of Wenzhou came to get in on the action and the operation ballooned in size.

The loans became almost impossible to pay off.

The Southern Weekly reported on the case of Liu Dapeng, who had borrowed four million RMB in 2011 because he wanted to invest in a fi sh pond, duck farm, and air-conditioning factory. Unsurprisingly, he was unable to make the payments, which amounted to 12 percent of the loan, every month. He fl ed but was later reportedly captured and tortured to death.

The Jinan Times cited estimates that said billions of RMB may have churned through Zouping County’s lending schemes over the years. Despite the scheme, the area’s growth grew through the entire period. Of fi cial estimates put the county’s total GDP at 53.8 billion RMB in 2010. By 2014, it had grown to 76.9 billion. In Sunzhen Township, locals said that at the height of the lending craze luxury cars clogged the streets. Later villagers would speak of communities left impoverished. But outside of the villages lies a vibrant private lending industry which in recent years has gone online. Gone are the local connections or family lenders, replaced by the impersonal ties offered by the internet.

Dubbed P2P lending, the process involves third parties who match lenders to those seeking loans. The process was on display in January of 2015, at the Internet Financial Summit in Beijing. There, Zheng Chunxiang, chief risk of fi cer at Subangloan. com, told the audience that since its founding in 2012, lending transactions had reached 1.06 billion yuan. And Subangloan is hardly the biggest player in the industry. Other competitors have amassed larger amounts of money, though it is rough going in a business which is expanding rapidly but also faces high rates of attrition. The risk of defaults is high, and some proprietors simply fl ee, taking the money with them.

In 2015, P2P industry information provider wangdaizhijia.com said that China had 1,575 P2P lenders at the close of 2014, with the total transaction value in 2014 amounting to around 252 billion RMB. That same year, 275 P2P lenders defaulted. The bigger survivors say that one of their biggest overheads is hiring all the staff required to properly scrutinize lenders.

Greater regulation is expected to arrive in 2015 along with slowing growth in the economy—a sure recipe for more defaults, but hopefully a more stable environment.

So for startups, venture capital is often the favored bet. Just several years ago aspiring companies had to struggle to fi nd any potential venture capital investors, but today they are proliferating.

The website of the largest industry group, the China Venture Capital and Private Equity Association, boasts that the organization has over 100 member fi rms, controlling 500 billion USD in assets—the vast majority of members being big players with at least 100 million USD in assets, with just over half of them being private equity funds and a third consisting of venture capital. Though it is worth bearing in mind that many may be based in Hong Kong, which is subject to entirely different rules than the mainland.

Citing research by Zero21PO Capital, a private equity group, Reuters reported that in the fi rst half of 2014, fresh capital available for investment had surged by 157 percent to around 6.76 billion USD—just shy of 42 billion RMB. In that period 83 venture capital funds were set up.

The Chinese government is now a direct player with its own startup fund, complete with resources set to rival the entire amount of fresh private capital put on the market in that same half-year period. In January of 2015 the authorities announced the establishment of a 40 billion RMB venture capital fund.

The announcement of the fund, which will support areas such as technology and green energy, came shortly after the authorities tweaked the rules to allow insurance companies to also get in on the action—they are now permitted to take cash from their massive insurance premium funds and put it into venture capital—the twin announcements further blurring the line between private and government ownership.

Foreign ownership is another very grey area. One lawyer intimately familiar with foreign investments in China revealed that while it was common for large multinationals to successfully conduct business in China, it was very common for those seeking to invest in startup companies to fi nd themselves on the losing end of disputes due to weak legal protections for minority investors, necessary due to strict requirements for startups to be helmed by Chinese citizens.

Foreign investors tend to come into Chinese mainland via investment vehicles registered in Hong Kong or Taiwan, or in some cases Chinese spouses, but the lawyer said that in decades of doing business in China, he had yet to see these foreign investors in mainland startups successfully “take-out” and get any large amounts of money back past out fl ow restrictions and into foreign accounts.

Nevertheless, the money continues to fl ow in, and with Chinese enterprises continuing to boom, few are looking to move their money elsewhere, at least not yet. And as other emerging markets continue to grow, the frontiers for Chinese startups will continue to expand.

——长春市第一中学学校特色