Analysis of the Stakeholder Engagement in the Deployment of Renewables and Smart Grid Technologies

Valeriia Vereshchagina, Mario Gstrein, and Bernd Teufel

Analysis of the Stakeholder Engagement in the Deployment of Renewables and Smart Grid Technologies

Valeriia Vereshchagina, Mario Gstrein, and Bernd Teufel

—The implementation of higher shares of renewables in a global energy mix has to be accompanied by simultaneous deployment of enabling smart grid technologies (SGTs). This combination will inevitably lead to a revolutionary change in a conventional energy system, particularly, the shifting role of consumers to prosumers. But resistance may arise from such a dramatic shift, since it is associated with high uncertainty in conjunction with increasing responsibilities of all stakeholders, the urgent need of effective control, and the development of a process. To ensure the positive influence, coherent actions of all players, and appropriate treatment of the spots of resistance, the analysis of the interplay between key stakeholders has been done. The paper introduces the framework for stakeholders’ analysis, applies it on the European Union (EU) example, and provides recommendations to reduce the resistance of SGTs deployment.

Index Terms—Communication strategy, crowd energy, renewable energy, smart grid technologies, stakeholder analysis.

1. Introduction

The trends are showing that the demand for energy is continued growing day-by-day leading to unbalance in existing grid systems. Moreover, the increasing energy consumption and high shares of fossil fuels in an energy mix increase environmental concern all over the world, forcing governments to join efforts in promoting the use of renewables. As long as higher shares of renewable energy (RE) have been implemented, the obsolete grid system has to be modernized accordingly to integrate renewables and to significantly increase the energy efficiency. Thus, the implementation of enabling technologies is vital.

The smart grid technologies (SGT) are seen to be an important step toward greener, cheaper, and more efficient energy use and help to achieve the renewable portfolio goals for many countries all over the world. However, the integration of innovative technologies that imply such a dramatic change in the conventional energy system requires congruent and coherent actions of all stakeholders. The example of the European Union shows that the ambitious goals set up under The Third Energy Package[1]are under the risk of being not fully accomplished. One of the main reasons for this could be the latent reluctance of certain stakeholders to actively participate in the deployment of SGTs and adapt to indispensable changes in an energy system. In order to identify the spots of resistance, the analysis of a system of the key stakeholders involved in a process of SGTs’ deployment is needed.

Thus, the authors propose a framework for the interplay of the energy stakeholders. First, developments in energy consumption, renewables, crowd energy and SGTs as well as the associated benefits and obstacles of their deployment are elaborated. Hereinafter, an analysis of the complex system is given taking into account the stakeholders’positive and negative impact. The framework is discussed on a European focus, but it can easily apply to other regions. Finally, a communication strategy presents public awareness campaigns, social advertising, and customer education for an actively promotion of the SGTs deployment.

2. Overview of Developments in an Energy Consumption

In the recent decades, society consumes continuously more energy to satisfy the demand of the growing economy and the related welfare. It is no wonder that the global energy consumption expects a growth by 56% in the period of 2010 to 2040 years, i.e. from 524 quadrillion British thermal units (Btu) to 820 quadrillion Btu[2]. The distribution of energy consumption by type of energy shows that liquids, coal, and natural gas are heading the chart with increasing volumes[2]. Even though, different energy forms present best dynamics for development, fossil fuels are keeping the leading position with the supply amount nearly 80% of world energy use through 2040[2].

Such trends are undesirable in the augmented sustainability mind-set; hence coal, oil, and natural gas are the main sources of CO2emissions[3]. Numerous initiatives and directives address this issue by advocating lower carbon emissions meaning the enforcement of enhanced energy production, distribution, and consumption.

The dynamics of sustainable energy systems involves also the electricity industry leading to higher shares of renewables in an energy mix. Today’s energy landscape in the European Union (EU) is active and shows positive tendencies for increasing renewable energy usage. For example, the EU achieves around 25% of renewables in total electricity supply and expresses further ambitious goals by doubling the share of renewables by 2030[4]. The challenge supports the development of RE and the implementation of SGTs.

3. Renewables and Smart Grid Technologies

3.1 Motivations for the SGTs Deployment

Much of the existing power system infrastructure built at 1950s or earlier is becoming obsolete and needs to be modernized in order to respond to the recent tendencies, such as increasing demand and power system loadings, which may lead to overstress of the system equipment. Furthermore, the electricity system becomes more complex due to the integration of distributed renewables causing a dislocation of generation sites and load centers (from a central network perspective)[5]. An impact is the introduction of SGT which allows a sophisticated allocation of production—integration of decentralized renewables—and consumption under the premise to reduce transmission and distribution. Thus, the intermittence of renewables has to be counter-balanced with more intelligence in a grid, base load power generation (hydro, nuclear), and storage[5].

The adaption of the electricity network is incremental and requires time; however, a powerful force for the SGTs deployment is the Energy Union. By creating pressure on member states, the EU drives the implementation of renewables and SGT. The major factor is the significant improvement of the energy usage efficiency. The leverage stems from its principles and objectives, which constitute the common and inevitable EU direction for all member states toward the creation of “… a sustainable, low-carbon and climate-friendly economy, integrated continent-wide energy system where energy flows freely across borders, based on competition and the best possible use of resources, and with effective regulation of energy markets at the EU level where necessary”[6].

For a successful translation of EU directives, the future intelligent system may consider different players like governments (national and regional), associations, business, and privates. This entails the understanding of different motivations, visions, and goals, but also the kind of stakeholders’ contributions to achieve a fruitful synergy. Additionally, a cooperation of varying stakeholders to achieve economic and ecological benefits allows addressing multiple goals.

3.2 SGTs, Renewables, and the New Scenario

The implementation of renewables is associated with a number of particularities, which have to be taken into account in order to allow higher RE penetration. Among the most important are variability and distributed generation, as well as new concepts such as the Crowd Energy.

With increased small-scale decentralized generation units, the electricity system dissociates itself from the traditional one-way flow of energy. Smart metering facilitates the two-way information flow, allows consumers to monitor prices, links the price signals to smart appliances, and provides detailed information on an electricity consumption, etc.[10]. SGTs allow system operators to observe real-time information and exercise significant control over the system, such as: reduction of output/disconnecting distributed generation if it threatens the reliability or matching load; real-time information on distributed generation electrical output; supporting the distribution system via voltage control[10].

SGTs contribute to the improvements of capacity of grid-connected renewables, such as: virtual power plant technology, which integrates renewable power sources; controlled load and energy storage system and active and reactive power flow control method which adopts frequency recovery algorithm based on frequency drop[11],[12]. Such RE sources as wind and solar are inherently intermittent, which creates the need for additional effort to ensure that electricity supply can meet demand at all times. SGTs can improve predictability and reliability. Implementation of such SGTs, as distributed storage, advanced sensing, control software, demand response, information infrastructure, and market signals, enhances the ability to influence and balance supply and demand[7],[8]. If the gap in RE generation occurs, the automated demand response will act as a lever that utilities can pull to help lower demand[9]. In order to optimize energy management, storage technologies become more important. Batteries store excess of energy and discharge it through the smart grid automation technologies when demand is higher than the supply[9]. Renewable energy forecasting contributes to variability issue. Nevertheless, such a system with intelligent generation-storage-load-cell (iGSL-cell)[13]entails a new electricity management philosophy.

The new scenario for the electricity management is based on crowd energy doctrine shifting the role of consumers who deploy RE at their homes[13]. They receive a bundle of new opportunities, such as: generation of ownenergy, storage and load and become prosumers[13]. As a result of decentralized and distributed architecture of an energy system, the energy turnaround becomes vital for the utilization of technological potential and its success. The crowd energy concept, then, means that numerous players of the energy market pool their resources via online information and communication technology-applications in order to ensure effective energy turnaround[13]. The resulted network represents a complex system of interconnected agents of an electrical grid (e.g. transmission and distribution system operators, power generation units, consumers, prosumers). The integration of prosumers into the system requires deep and comprehensive study of their behavior and motivation in order to achieve behavioral predictability and elaborate sufficient tools of control.

3.3 Benefits of SGTs Deployment

Accordingly to McGregor et al.[14], the bundle of benefits associated with integration of SGTs along with RE will lead to economic gains from improved reliability, better public health due to significant reduction of emissions and long-term economic and environmental gains from low-carbon electricity. Increasing shares of renewables reduces a country’s dependence on foreign fossil fuels, significantly decreasing import volumes and, at the same time, ensuring higher levels of a country’s energy security and autonomy, which along with SGTs deployment promise more efficient use of energy in a country[15]. This is especially important in light of recent events when the prices for oil have become a political weapon and thus have brought instability. The combination of RE and SGT has a good argument to support a reliable network during possible grid failures. Customers may reduce their energy bills through advanced control of the energy management, particularly, by consuming energy at off-peak charging hours, installing energy efficient appliances, selling excess of generated energy as well as choosing low-carbon energy supply.

3.4 Obstacles of SGTs Deployment

The interaction and cooperation between different stakeholders (end-user, suppliers, providers etc.) is complicated since the research in technology is still in progress. Understanding and communicating the value proposition of SGTs deployment for each stakeholder in the electricity supply chain may be complicated as far as the implementation requires high initial costs while providing rather uncertain results. It is combined with the lack of appropriate incentive structure that has to align economic and regulatory policy with environmental objectives and efficient use of energy[15]. The awareness of such positive outcomes of SGTs deployment as the creation of new working places and advancement of technically skilled labor is under developed[15]. At the same time, the lack of experience, associated uncertainties of the cost and performance and non-technical issues such as data privacy represent additional challenges to make the best use of technologies[10].

4. Interplay of the Key Stakeholders

Cooperation among the involved stakeholders achieves synergy and produces substantial benefits to the system but also to each party, such as the increase of independence of fossil fuels, facilitation of energy efficiency through a number of energy efficiency programs, achievement of planned shares of renewables, reduction of the carbon output, protection of the environment, and the improvement of public health, as well as, numerous economic benefits. These

variousinterests

are

crucial

fora

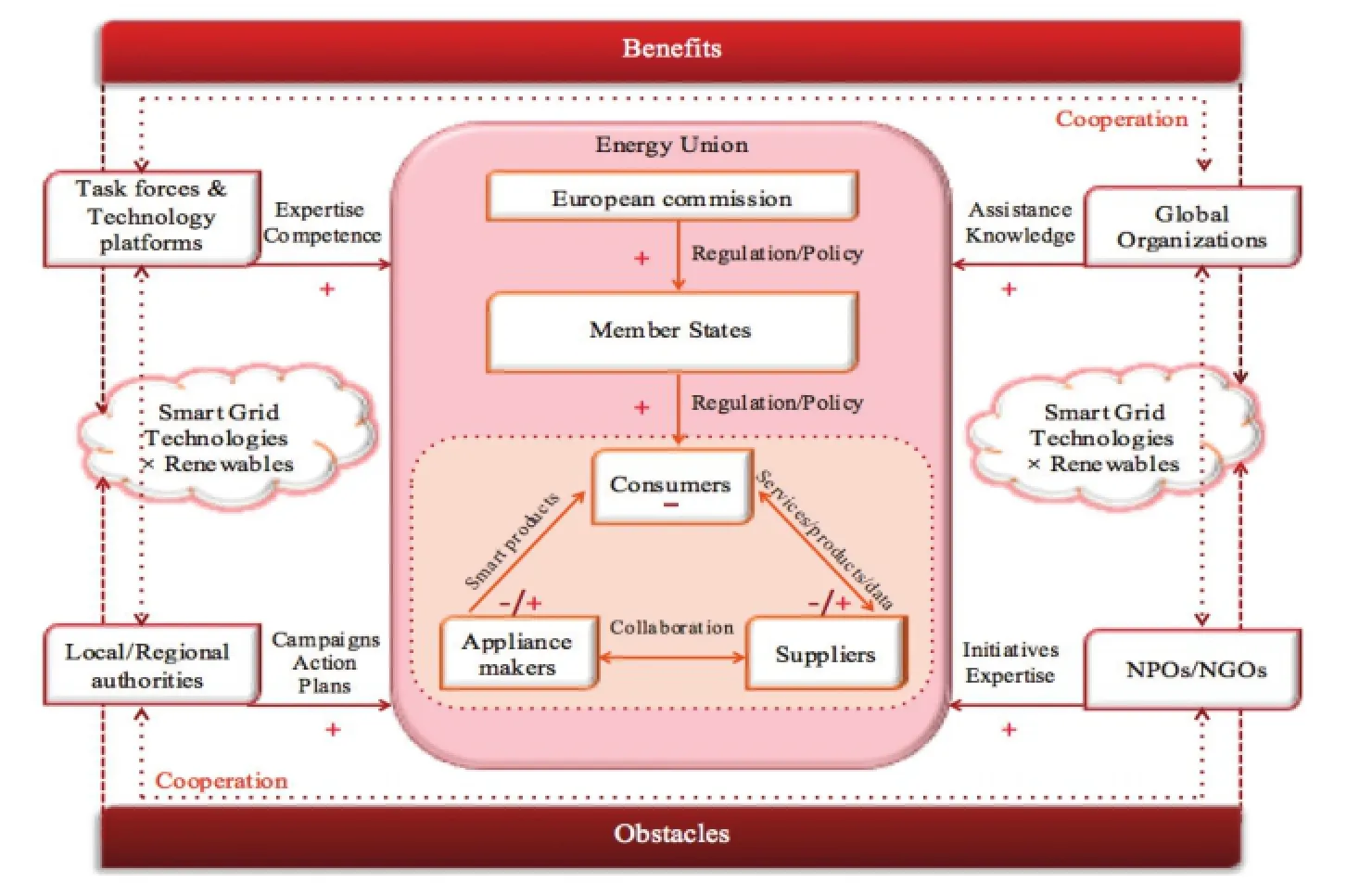

Fig. 1. Interplay of the key stakeholders in the EU.

successfuldeployment of RE and SGTs and hence an in-depth analysis of the stakeholders’ relationships and influences is necessary. Fig. 1 depicts the holistic view of the complex electricity system in which different stakeholders have positive or negative impacts on the deployment of renewables and SGTs. The framework covers not only the main players, but also the benefits and obstacles, which help to determine the sign of the influence. The framework can be applied to other countries or regions with specific adaptations, such as the existence of unique circumstances (e.g. Energy Union in case of the EU) or the structure of policy-makers (in case of EU, it is 2 layers: EU-wide and nation-wide).

4.1 Global Organizations

Among large number of powerful global organizations, which influence SGTs and RE implementation, 3 groups can be identified: technology development organizations (e.g. Global Smart Grid Federation), organizations involved in development of directions for the energy industry (e.g. International Renewable Energy Agency), and environmental organizations (e.g. Greenpeace, WWF). Technology development organizations aim to bring together all SGTs related initiatives around the world and facilitate the worldwide knowledge transfer. The organizations represent the global centers for competency on SGTs and policy issues, facilitate cooperation between public and private sectors around the world, and release reports and overviews on related issues. Organizations involved in the development of directions for the energy industry aim to assist countries worldwide to fulfill their RE and efficiency goals by providing necessary data and statistics, advices on policy developments, and insights on financial issues and technological expertise. Environmental organizations are actively working on the field of popularization of sustainable energy and innovative technologies and playing a role of energy policy advisor. Such organizations provide ideas, solutions, calculations, methods, and strategies helping to overcome the main obstacles and resolve vital problems associated with RE and SGTs deployment in the most efficient way. The global organizations are showing strong interest in the implementation of smart grid technologies and influencing the development positively.

4.2 Local Non-Profit and Non-Governmental Organizations

At the energy industry most of non-profit organizations (NPOs) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) create associations in order to pool efforts, resources and, thus, increase their power and influence on policy-making authorities. Renewable Grid Initiative (RGI) is a good example of such an association. RGI consists of NGOs (including environmental groups) and transmission system operators (TSOs) advocating national and EU authorities to focus on efficient, sustainable, clean, and socially accepted development of the energy infrastructure for both smalland large-scale RE generators[16]. Among the non-profit organizations the most prominent is The Council of European Energy Regulators (CEER), which represents the interests of Europe’s national regulators of electricity and gas at the EU and international levels. CEER allows national regulators to cooperate, exchange knowledge, and share the best practices. NPOs and NGOs can positively influence the SGTs and RE deployment by providing related initiatives to the policy-making authorities.

4.3 Technology Platforms and Task Forces

Technology platforms and task forces represent different types of stakeholders. Technology platforms are the specific places where the knowledge and competences are accumulated, processed, and disseminated by participants. Technology platforms aim to provide a strategic navigation on the development of SGTs for the numerous stakeholders, where they bring together: policymakers, TSOs, distribution system operators (DSOs), manufacturers, large- and small-scale electricity generators, prosumer organizations, research centers, academia etc. Specifically, in the EU, the Smart Grids European Technology Platform (ETP SG) mobilizes stakeholders, facilitates the exchange of knowledge, and organizes the events for improved two-way communication process such as joint workshops with national smart grid platforms.

Task forces are usually set up temporarily by regulators with the main purpose—to fulfill the mission, which was induced by the creator. For example, the European Commission has established the Smart Grid Task Force (SG Task Force) to examine several issues associated with SGTs deployment and to provide an advice directly to the EU on policy and regulatory directions concentrating on the EU-wide level and to coordinate steps for the SGTs deployment under the provision of the Third Energy Package. The five expert groups produced a number of reports concerning data privacy, standardization, and data management models. Task Forces and Technology Platforms provide critical informative and supportive assistance and expertise, thus, positively influence the SGTs and RE deployment.

4.4 Associations of Local and Regional Authorities

Local and regional authorities may pool their efforts and take an active participation in achieving governmental energy-related goals. Since they are the closest link to the citizens they have a direct access to them and understand them better, meaning they can organize a number of programs, which involve private households and local business. In EU, this role plays a Covenant of Mayors whose main aim is to put efforts together in order to meetand exceed the EU objective of a 20 % reduction in CO2by 2020 through the enhanced efficiency and the focus on the development of RE. The covenants of mayors acting through the sustainable energy action plan which signatories have to develop and submit on a voluntary basis.

4.5 Policymaker

The European Parliament is a legislative branch of the EU, which enacts policies and legislation into law. After that, the European Commission enforces policies and legislation through directives, regulations, and decisions that take precedence over national law and are binding on national authorities. The European Commission also provides recommendations and opinions, which can be taken into account by national authorities on a voluntary basis. In order to achieve the cost-effective, efficient, and consistent implementation of the new energy grids, according to the directives form the Third Energy Package, which requires, also, that at least 80% of European households have to deploy smart meters by 2020[17], the European Commission has established such organizations as ETP SG, SG task force.

4.6 Interplay of Consumers, Suppliers, and Appliance Makers

The relationships between consumers, suppliers, and appliance makers create a triangle, which represents the distinctive system in which the formal and informal rules, policies, and laws materialize and become real. This system could be seen as an indicator of whether other stakeholders’regulation and policies are harmonious and non-contradictory. The situation when all stakeholders display positive influence and sincere interest may, still, produce negative results. The root of the problem lies in congruence. Numerous stakeholders may have positive influence. But the lack of synergy and alignment between different functions, visions (especially in task prioritization), and actions may cause the opposite effect and lead to or worsen existing problems. In the EU the triangle represented resistance in RE and SGTs deployment.

The suppliers (TSOs, DSOs, utilities, etc.) in their relationships with consumers risk being overly technocratic in their communicating approach. Lack of understandable dialogue between utilities and consumers already resulted with unsatisfied consumer participation rates in the smart grid projects[18]. Utilities, TSOs, and DSOs are providing customers with a bundle of services, products, solutions, and data. The milestone in the relationships is data flows, which suppose to be a bi-directional, from suppliers to customers and vice versa. It leads to increasing concerns about data privacy and ownership, as long as, utilities require data to ensure system reliability and such issues as access to consumers’ data, the security has to be negotiated between utilities and consumers. Another issue in consumer-utility relationships is that utilities are concerned of losing their revenues, because more and more distributed renewables will be deployed by private households. In addition to complicated relationships with suppliers, consumers are not predominantly aware of, or do not perfectly understand the nature of such innovative technology as SGTs, as well as, the increased responsibilities associated with its deployment and the future of a crowd energy, and its benefits.

Appliance makers and utilities collaborate to boost the demand on smart appliances. In fact, utilities can use numerous networked appliances (e.g. water heaters) to tap to prevent blackouts. Moreover utilities can “…build into their future planning to avoid building or buying new peak power generation or transmission and distribution grid upgrades”[19]. However, the appliance makers have marginal interests in production of smart appliances if there will not be enough demand. The demand, in turn, is directly related to the consumers’ awareness of the whole shift in the energy system. For example, consumers may be not aware that SGTs are not motivated to buy smart appliances, but it would be beneficial only in case of simultaneous integration with SGTs. Consumer’s reluctance to deploy SGTs and participate in crowd energy leads to increasing resistance from suppliers and appliance makers as well, since only consumers’ high involvement may insure the win-win situation for all the parties.

5. Recommendations

The new prosumers within the intelligent generation-storage-load-cell (iGSL-cell) structure[13]promote new requirements for the energy management in order to capture new opportunities and harmonically integrate the new actors into an energy system. Stakeholders in the triangle represent highly dependent interconnected units, which mean the resistance at one unit may provoke resistance in other units. The implementation of higher shares of renewables and SGTs affect all processes and lead to full reconsideration of the roles in the triangle and, consequently, the managerial approaches. Prosumers are seen to represent the main source of resistance. At the same time the predictability and manageability of their behavior are crucial for smooth integration of renewables, SGTs, and the crowd energy[20]. Thus, the EU has to put more attention to socio-psychological aspect of the integration of innovative technologies in an energy sector.

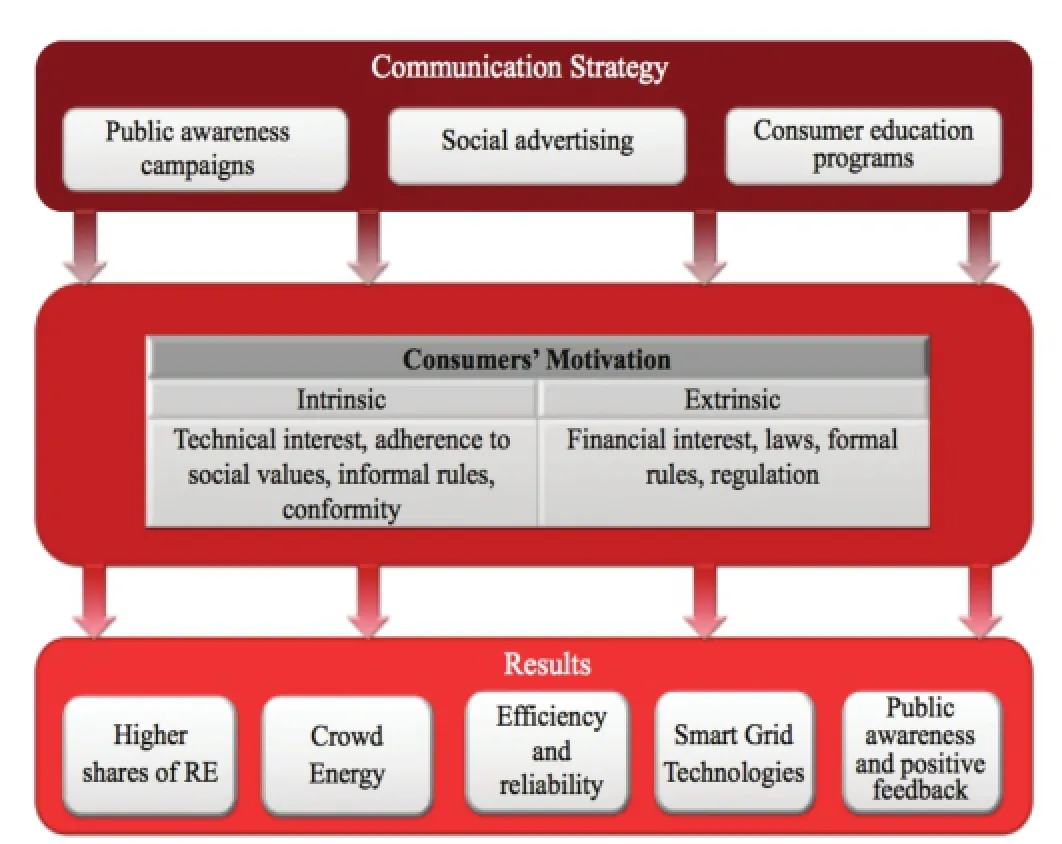

The European Commission identifies public awareness and acceptance of SGTs as one of the key challenges in meeting the goals of the Third Energy Package[21]. Mc Kinsey highlights the lack of consumers’ demand for SGTs, supporting the statement with a survey results showing only 32% of British understand what a smart meter is, eventhough, in 2009 the debate over the issue was extensively covered by local media[22]. Such dynamic is due the fact that consumers are not aware of benefits of SGTs deployment, but they face high initial costs of the implementation, data privacy, and data security and uncertainty about economic outcomes, i.e. they lack motivation to overtake active part in the process. To overcome this obstacle, the government’s challenge is the supervision of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation through a communication strategy. This includes public awareness campaigns, social advertising, and customer education (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Expected impact of the implementation of the communication strategy.

The idea of public awareness campaigns is to communicate the idea of significant benefits, which stems from the deployment of SGTs that have to be accompanied by the explanation of what SGTs are in general. In order to do so, the demonstration projects might be launched. The local authorities have to ensure active participation of consumers in demand-response demonstration programs and allow consumers to figure out how the process is done and what the consequences are. It is also necessary to ensure the data privacy and security, because data sensing and monitoring functionalities are embedded in SGTs[23]. Therefore, one of the necessary elements of awareness campaigns should be the explanation of how the government is going to ensure the safety in such issues, and provide standards and certificates needed to ensure the appropriate use of private data. National governments have potential to educate consumers on the benefits and necessity of SGTs, with regard to consumer-oriented issues, such as affordability, privacy, cyber-security, health, and safety[23].

Social advertising is one of the most effective instruments in approaching the large auditory. Considering the EU level, the Covenant of Mayors jointly with Renewable Grid Initiative would elaborate the standardized social advertising (which can be used in all member states with the purpose of achieving economies of scale). The social advertising may include authentic consumer testimonials, which have experienced benefits from the deployment of the SGT. When the awareness of SGTs in a community is low, it is necessary to construct the communicated massage in an understandable way considering appropriate levels of complexity. After a particular period of time, the survey has to be conducted to measure the level of awareness and the attitude about the SGTs and RE. If the results will be positive, more complex messages can be conveyed to enhance consumers’involvement.

Consumer education programs could be an effective instrument not only in the dissemination of information, but what is more important, in the context of the crowd energy, it may be an effective tool of shaping the consumers’behavior. National governments jointly with SGT oriented NGOs and NPOs may elaborate brief educating programs which will comprise the overview of directions of the development of energy policies in the EU, and convey the concepts of SGTs, RE integration, and the crowd energy. The programs communicate the benefits of the smarter usage of energy and shape the consumption behavior of current energy users who in the nearest future will make their own energy-use decisions.

As Fig. 2 shows the set of measures are directed to influence the intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (see [24], [25] as examples) of consumers to deploy renewables and SGTs, participate in crowd energy, improve efficiency and reliability in an energy system as well as increase public awareness and positive feedback. Through the impact on extrinsic motives, the EU government will facilitate the awareness of consumers about potential financial gains, related laws and regulation, and formal rules (formal rules may take place between consumers/prosumers and suppliers). Through the impact on consumers’ intrinsic motives, the EU government receives the opportunity to shape and predict energy consumption behavior as well as reduce consumers’/prosumers’ latent resistance through the formation of the system of appropriate social values and norms (informal rules).

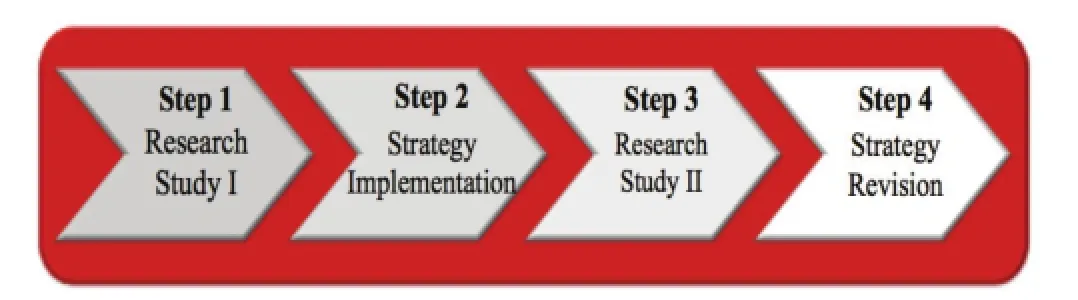

To ensure the successful implementation of the communication strategy, several steps have to be taken (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Implementation process of the communication strategy.

The first step implies a region-wide study, which consists of qualitative and quantitative research of the consumers’ awareness and attitudes about the SGTs and the crowd energy. Using the example of the EU, the European Commission may delegate this task to the Smart Grid Task Force, which owns the necessary expertise and resources. The second step implies the implementation of the communication strategy. At this step, it is advisable to involve policy-makers, NGOs/NPOs, and local and regional authorities in order to pool efforts, expertise, and resources. This is especially important for the EU, because the communication strategy has to function well in rather heterogeneous cultural environment. During the third step the region-wide study has to be repeated. The third step aims to evaluate the effectiveness of the communication strategy and track the progress. The fourth step implies the adequate respond to the third-step findings. In case of positive evaluation of the results, the decision-making body may be chosen to proceed with the communications strategy. In case of negative evaluation of the results, the obstacles have to be identified and eliminated, and appropriate adjustments to the strategy have to be made.

6. Conclusions

The recent global trends have shown that the implementation of higher shares of renewables and SGTs is inevitable. To achieve the ambitious goals associated with the transformation of the conventional energy system, numerous stakeholders pool their efforts trying to create synergy and overcome obstacles. However, consumers are still cautious about the implementation of SGTs, because of generally low awareness about benefits in combination with a number of obvious threats, which distort their motivation to take active participation in the process. In order to achieve high levels of involvement and motivation among consumers, governments have to improve their communication strategies by the implementation of the set of measures: public awareness campaigns, social advertising, and customer education programs. The measures are called to improve the extrinsic and intrinsic motivation, awareness, predictability, and manageability of consumers’/prosumers’ behavior within the crowd energy concept and will lead to the deployment of higher shares of renewables and SGTs. The framework and the recommendations were presented on the EU example but can be applied to other regions as well.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the members of the crowd energy and smart living lab research groups at the International Institute of Management in Technology (iimt) for fruitful discussions on the topic.

[1] European Commission. (2015). Overview of the market legislation. [Online]. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/ node/50

[2] Intl. Energy Outlook 2013, U.S. Energy Information Administration, Washington, DC, Jul. 2013.

[3] Key World Energy Statistics, Intl. Energy Agency, Paris, Sep. 2014.

[4] A. M. Canete. (March 2015). Innovative smart grids central to energy union. [Online]. Available: http://ec.europa.eu/ energy/en/news/innovative-smart-grids-central-energy-union

[5] E. E.-H. Mohamed, “The smart grid—state-of-the-art and future trends,” Electric Power Components and Systems, vol. 42, no. 3-4, pp. 239-250, 2014.

[6] Energy Union Package: A Framework Strategy for a Resilient Energy Union with a Forward-Looking Climate Change Policy, European Commission, Brussels, Feb. 25 2015.

[7] M. Paget, T. Secrest, and S. Widergren, Using Smart Grids to Enhance Use of Energy-Efficiency and Renewable-Energy Technologies, APEC Energy Working Group, 2011.

[8] R. Zhou, Z. Li, and C. Wu, “An online procurement auction for power demand response in storage-assisted smart grids,”in Proc. of IEEE INFOCOM, Hong Kong, 2015.

[9] M. Chapman and A. Eckelkamp, Cleaner energy—Delivered by a Smarter Grid, General Electric Company, GEA-10002MC, 2009.

[10] R. Kempener, P. Komor, and A. Hoke. (2013). Smart grids and renewables: A guide for effective deployment. Intl. Renewable Energy Agency. [Online]. Available: http://www. irena.org/DocumentDownloads/Publications/smart_grids.pdf

[11] F. Katiraei and M. Iravani, “Power management strategies for a microgrid with multiple distributed generation units,” IEEE Trans. on Power Apparatus and Systems, vol. 21, pp. 1821-1831, Nov. 2006.

[12] Z. Hu, C. Li, Y. Cao, B. Fang, L. He, and M. Zhang, “How smart grid contributes to energy sustainability,” Energy Procedia, vol. 61, pp. 858-861, 2014, doi:10.1016/ j.egypro.2014.11.982

[13] S. Teufel and B. Teufel, “The crowd energy concept,”Journal of Electronic Science and Technology, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 263-267, Sep. 2014.

[14] T. McGregor. (2012). Realizing the value of an optimized electric grid. Gridwise Alliance. [Online]. Available: http://www.smartgridinformation.info/pdf/4902_doc_1.pdf

[15] N. V. Vader and M. V. Bhadang, “System integration: smart grid with renewable energy,” Intl. Journal of Renewable Energy Exchange, vol. 3, no. 1, pp.1-13, 2013.

[16] The Power of Collaboration: A Short Introduction to the Work of RGI, Renewable Grid Initiative, Berlin, 2015.

[17] Directive 2009/72/EC of The European Parliament and of The Council concerning common rules for the internal market in electricity. Official Journal of the European Union. [Online]. pp. 55-93. Available: http://www.detini.gov.uk/ electricity_directive_2009-72-ec_oj.pdf

[18] S.-Y. L. Lee, The Global Smart Grid Federation Report, The Global Smart Grid Federation, Canada, 2012.

[19] J. St. John. (Feb. 2013). A new standard for the smart-grid-ready home appliance. Greentech Media. [Online]. Available: http://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/anew-standard-for-the-smart-grid-ready-home-appliance

[20] M. Gstrein and S. Teufel, “The changing decision patterns of the consumer in a decentralized smart grid,” in Proc. of 2014 the 11th Intl. Conf. on the European Energy Market, Krakow, 2014, pp. 1-5.

[21] M. Sánchez. (Oct. 2014.). Challenges and framework for Smart Grids deployment. [Online]. Available: http://www.jaspersnetwork.org/download/attachments/18743 427/2.%20JASPERS%20NP%20Smart%20Grids%2025%20 March%202015%20-%20DG%20ENER%20.pdf?version=1 &modificationDate=1427306833000&api=v2

[22] E. Giglioli, C. Panzacchi, and L. Senni. (2010). How Europe is approaching the smart grid. [Online]. Available: http://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/dotcom/client_ service/EPNG/PDFs/McK%20on%20smart%20grids/MoSG_ Europe_VF.aspx

[23] Smart Grids: Best Practice Fundamentals for a Modern Energy System, World Energy Council, London, 2012.

[24] R. Ryan and E. Deci, “Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions,” Journal of Contemporary Educational Psychology, vol. 25, pp. 54-67, Jan. 2000.

[25] O. Cinar, C. Bektas, and I. Aslan, “A motivation study on the effectiveness of intrinsic and extrinsic factors,” Journal of Economics and Management, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 690-695, 2011.

Valeriia Vereshchaginawas born in Dresden, Germany in 1991. She received the B.S. degree in management of innovative and investment activities and the M.S. degree (with Honours) in management and administration, both from the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Ukraine in 2012 and 2014, respectively. She worked as an assistant manager at Country Plus, Ltd., Kyiv from July 2012 to October 2013. Currently, she is pursuing her master degree in European business at the University of Fribourg, Switzerland. Her research interests include strategic management, smart grid technologies, and crowd energy.

Mario Gstreinstudied business administration and informatics at the Berufsakademie Lörrach (GER) and received the B.Sc. degree in 2001. He received the M.Sc. degree in innovation and technology management at the Science and Policy Research Unit (SPRU), University of Sussex (UK).HeiscurrentlypursuingthePh.D. degree with the International Institute of Management in Technology (iimt), University of Fribourg, Switzerland. His research interests include energy systems, electricity management, innovation management, value network, and simulation of complex systems.

Bernd Teufelstudied computer science (Informatik) at the University of Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe, Germany. Subsequently he joined the Department of Computer Science, ETH Zurich, where he received his Doctor’s degree (Ph.D.) in 1989. He was a lecturer at the Department of Computer Science, University ofWollongong,Australia,andascientific consultant with Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO), Sydney, before he founded the company“ART Informationssysteme GmbH” in Germany. After several mergers, he left the organization in 2008 and founded the consulting agency “Dr. Teufel Consultancy Services” in Switzerland in 2009, which mainly focuses on independent research consultancy. His research interests include ICT-management, social media, management of energy systems, energy turnaround, innovation and project management.

Manuscript received May 12, 2015; revised July 25, 2015.

V. Vereshchagina and M. Gstrein are with International Institute of Management in Technology, University of Fribourg, Fribourg 1700, Switzerland (e-mail: mario.gstrein@unifr.ch).

B. Teufel is with the International Institute of Management in Technology, University of Fribourg, Fribourg 1700, Switzerland (Corresponding author e-mail: bernd.teufel@unifr.ch).

Digital Object Identifier: 10.11989/JEST.1674-862X.505121

Journal of Electronic Science and Technology2015年3期

Journal of Electronic Science and Technology2015年3期

- Journal of Electronic Science and Technology的其它文章

- Energy Management Strategies for Modern Electric Vehicles Using MATLAB/Simulink

- Hybrid Aging Delay Model Considering the PBTI and TDDB

- Time-Efficient Identification Method for Aging Critical Gates Considering Topological Connection

- Residual Phase Noise and Time Jitters of Single-Chip Digital Frequency Dividers

- A Methodology to Measure the Environmental Impact of ICT Operating Systems across Different Device Platforms

- Enhancement of Distributed Generation by Using Custom Power Device