Rethinking Enterprise Architecture for Sustainable Energy System Development

Jovita Vasauskaite and Asif Qumer Gill

Rethinking Enterprise Architecture for Sustainable Energy System Development

Jovita Vasauskaite and Asif Qumer Gill

—The development of a sustainable energy system throughout an enterprise is a complex task, which requires an agile holistic approach. Such an approach needs to include a variety of objectives including energy strategy formation and strategic decision-making, which are directly related to the analysis and management of the main areas of sustainable development: The economic, technological, environmental, and social. These multidimensional requirements of sustainability are often difficult to achieve within the enterprise, because these aspects are interrelated and influenced by various internal and external environment factors. This paper first reviews the main challenges for an energy system, and then demonstrates how a strategic agile enterprise architecture driven approach could effectively guide the sustainable energy system development. The study presented in this paper provides a holistic approach that contributes to the advancement and usage of literature dealing with issues of sustainable energy system development and agile enterprise architecture, which has not been discussed before to any great extent.

Index Terms—Development, energy system, enterprise architecture, industry, sustainability.

1. Introduction

Enterprises are confronted with a new challenge of sustainability due to the global environmental deterioration, transformation in power industry, demanding energy policies, decentralisation, natural resources depletion, and society pursuing higher life quality. The enterprises need to carefully consider their strategic actions to deal with the sustainability challenge which are targeted towards gaining the competitive position, the formation and maintaining of a long-term competitive advantage in order to achieve favourable financial results in the particular market or industry[1]. The planning and implementation of strategies and design processes of an enterprise should incorporate many internal and external aspects of the enterprise[2]. Some of them are related to the overall political, economic, social, environmental, and technological areas. Other factors reflect the inner aspects: Change of energy sources using a wider range of equipments, reduction of resources consumption and production costs, shortening of production cycle, and improvement of production quality. Multidimensional requirements of sustainability are often difficult to achieve because these aspects are interrelated in a complex way. The strategic actions of an enterprise can be realised through the design of the enterprise architecture[3].

Enterprise architecture is an important discipline for describing the holistic and integrated complex human (business, information, and social), information technology (IT) (application, platform, and infrastructure), and facility (e.g., spatial, energy, etc.) layers of an enterprise[4]. These layers can be reviewed to identify the strategic requirements of the energy efficient technology for creating an adaptive and sustainable enterprise. For instance, a spatial architecture (e.g., data center facility, office location), within the facility layer, is built to support the human and IT architectures. The spatial architecture is supported by the energy architecture. The energy architecture describes the energy elements (energy supply chain) that supply power for the smooth running of the energy efficient or sustainable enterprise. Hence, the enterprise is a key to understand and identify the requirements of the energy efficient technology at different architecture layers such as the energy requirements for the human, IT, and facility architectures. This enterprise architecture driven approach could lead to the sourcing or development of a sustainable energy system.

There have been significant efforts over the last decade to define appropriate theories and best practices and construct the consistent sustainable energy system to increase and maintain energy savings[5]-[7]. A lot of researches have been focusing on environmental innovations, particularly related to the intensity of emissions, energy efficiency, and economic performance. Thus, the areas of scientific research works have beenwidely expanded and focused on the development of knowledge, related with energy efficiency, renewable energy, energy management, and the implementation of energy saving technologies[9]-[11]. The importance of the sustainable energy system has been stressed by many scientists[5],[12],[13]. Countless reports have been written on the subject of sustainable energy, but few have approached this specifically from the perspective of an enterprise architecture approach. There is a need of a strategic and agile approach to guide the sustainable energy system development.

The aim of this paper is to propose and demonstrate a strategic agile enterprise architecture driven approach that could effectively guide the sustainable energy system development.

2. Sustainable Enterprise Architecture Concept

The development and management of a complex sustainable energy system is not an easy task. It can be assisted by a holistic and strategic enterprise architecture approach[4]. The architecture is defined as the fundamental concept or property of a system in its environment embodied in its elements, relationships, and the principles of its design and evolution[14].

The “system” concept, in the definition, can be used to refer to a number of systems, such as the information and communication (ICT) system, energy system, and facility system, etc. The enterprise architecture is a strategic approach that can be used to describe the system design principle properties, elements, environment, and their relationships. It includes diverse views of the enterprise[15]: The strategy view including tactical and strategic goals and evaluation metrics to achieve them, the capability view which regards the primary enterprise functions and the units that perform them, the value stream view which refers to the set of activities that deliver value to external and internal stakeholders, knowledge view which concerns the vocabulary of the organization to communicate and structure the understanding among the different units, and the organizational view including the relationships among roles, capabilities, business units, and the internal and external management of these units.

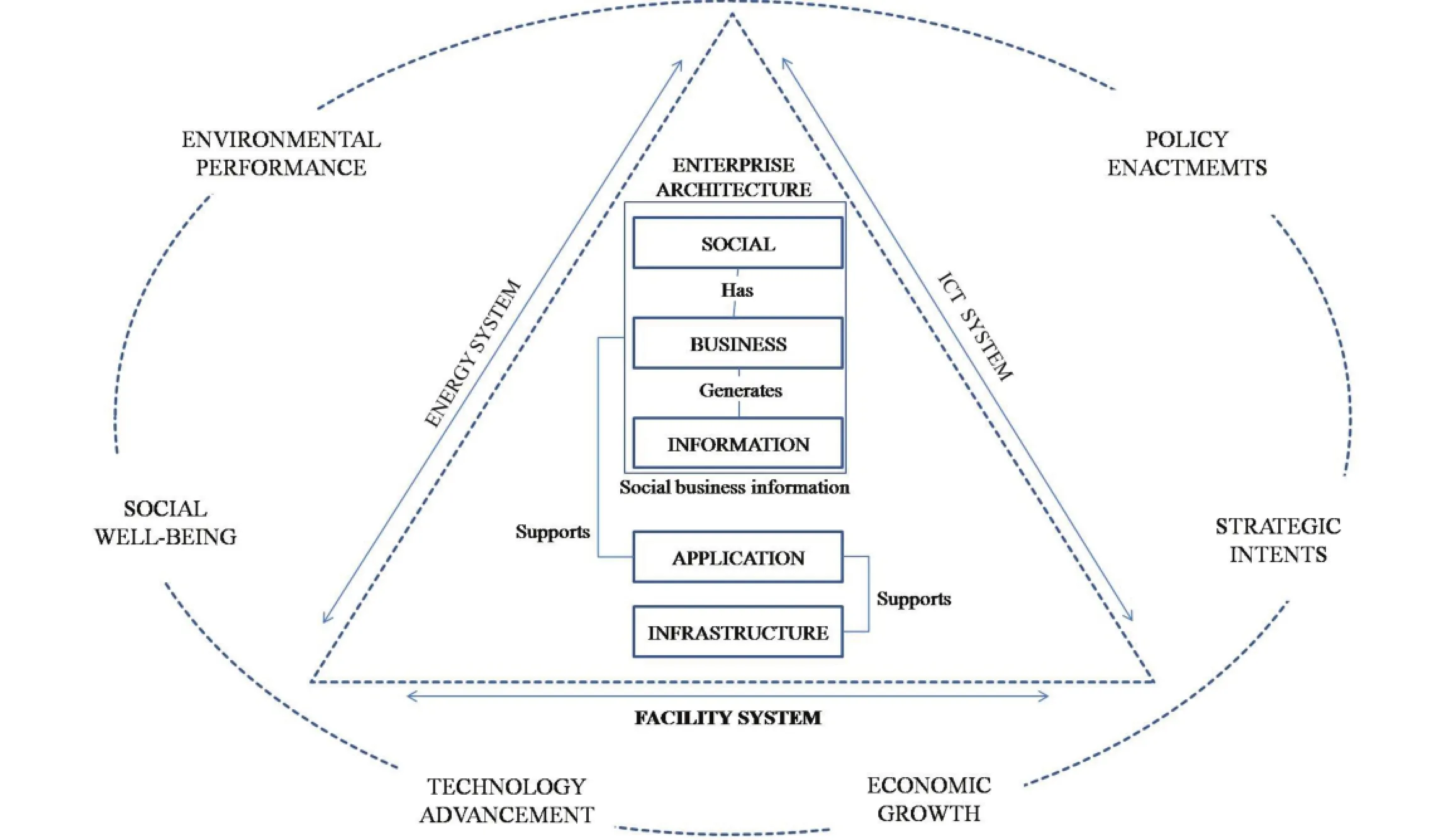

Fig. 1. Sustainable enterprise architecture concept.

The key concept of the enterprise architecture and the influencing factors are depicted in Fig. 1. The enterprise architecture is a blueprint that encompasses different architecture layers such as social, business, information, application, and infrastructure architectures including platform layer. These layers describe the overall architectures of a system that share common goals and principles[16],[17].

The business layer refers to the business architecture of an enterprise which includes business actors, capabilities, processes, services, and products. In addition to the formal business structure or architecture, it has also a social architecture. The social architecture layer describes the social or human aspects of a business such as business culture, human behaviour, motivations, and beliefs, etc. The business generates or is dependent on the effective management of business information, which may be required to run business operations and support decisions (e.g., technological decisions and investment decisions). Therefore, the information architecture is an integral part of the business architecture, which is focused on handling the business information. These integrated layers define the social business information (SBI) architecture within the context of the overall enterprise architectures.

The integrated SBI is supported by the applications such as social (e.g., Facebook and Twitter), business (e.g., energy, customer, and financial), and information (e.g., information management and analytics) software applications. The application architecture supports the SBI and describes various applications and their relationships. The application architecture is supported by the infrastructure architecture (including application development and deployment platforms) that describes the technology resources, such as computing, storage, and network. These integrated layers of the enterprise architecture provide a holistic lens to define energy and ICT systems. The facility system provides the spatial environment (e.g., data center, building, and grid station) for hosting the energy and ICT systems.

Further, the design of the enterprise architecture can be influenced by a number of internal and external factors, also shown in Fig. 1, such as strategic intents, economic growth, policy enactments, technology advancements, social well-being, and environmental performance following related factors.

A. Technology Advancement

Technology brings both intangible and tangible benefits to become cost efficient and to meet the growing demands and needs of customers. The technological innovations continue to revolutionize the way enterprises conduct business and execute business processes (e.g., cloud-based computing and green technology). However, one must understand that the technologies which are available in today’s time span will likely become obsolescent in subsequent eras, and the requirements of today’s era will likely vary from those of subsequent eras[12]. Therefore, enterprises are looking for new solutions to embrace these technologies from an access, integration, and deployment perspective.

B. Social Well-Being

Enterprises affect people’s well-being in many ways, for example through employment and the quality of services they provide or goods they produce. It may also have smaller effects on broader stakeholder groups, such as the communities they operate within (e.g., corporate responsibility programs). Social well-being should be considered one of the ultimate aims of society—alongside social justice and ecological sustainability.

C. Environmental Performance

The strictness of environmental legislation and regulation ensures the enterprise movement from polluting activities towards cleaner production processes. The established international standard provides recommendations to enterprises how to develop their improvement of environmental performance and energy management, etc., e.g. ISO 14031 for environmental management and ISO 150001 for energy management[1].

D. Strategic Intents

Business has a vision which derives the business goals. These goals can be achieved via strategic intents or initiatives[18]. The strategic initiatives describe the overall business motivations and directions. These initiatives could be business or technology related initiatives, which are realised by the enterprise architecture.

E. Policy Enactments

The realisation of the strategic intents is guided by the policy[4]. The policy enactment refers to the enforcement of specific rules. An enterprise can develop a number of polices suitable to their context such business policy, information management policy, and energy policy, etc.

F. Economic Growth

It means an increase in the value of goods and services produced in an economy. In the long run development of new technologies, the investment in facilities and human capital are the key factors in enabling improved productivity and higher economic growth. The economic growth is a combination of higher productivity and higher consumption of raw materials and also invariably leads to higher consumption of non renewable resources.

When the challenges within an enterprise are visible from all of these various perspectives, enterprise transformation is required to implement the fundamental change across the functional boundaries and can affect their policies, strategies, processes, and cultures. This overview of the sustainable enterprise architecture concept brings up the needs to consider the interdependency between the internal and external systems, processes, and other elements of an enterprise which are often complexly integrated. The objective of the next section is to identify both the internal and external drivers and challenges of the energy system development, which appears to be one of the coreinfrastructure components in the sustainable enterprise architecture concept.

3. Challenges for Sustainable Energy System Development

Modern enterprises, driven by a number of environmental, political, and societal concerns, are focusing on higher standards developing sustainability strategies to remain competitive in the markets. By focusing on the changing nature of the energy infrastructure and the inherent challenges that arise as energy availability becomes scarcer, it becomes evident that a more sustainable energy infrastructure can lead to enterprises being able to deliver more value using fewer resources[12]. Solutions for sustainable energy system development could be provided through[19]:

· The use of an interdisciplinary approach for research, planning, implementation, and linking fields such as ecology, economics, engineering, business management, public administration, and law;

· A holistic systems’ approach to resource management, balancing environmental issues with economic and industrial viability;

· Examination of material and energy flows through complex industrial systems;

· Reduction of energy and material flows used for production and consumption to moderate impacts on the environment to levels that the natural systems can sustain;

· The organized co-location of manufacturing activities to supply neighbouring businesses with waste or energy surplus for reuse and/or reprocessing purposes;

· The creation of strategies to increase manufacturing efficiency and effectiveness while reducing the impacts of flows;

· The re-design of manufacturing development to include activities which have reduced the human ecological impacts.

Sustainable energy development is based on three fundamental policy trends: Energy independence, competitiveness, and sustainable development. The sustainable development is defined as the development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs[20]. Sustainable energy strategies become a matter of introducing and adding flexible energy technologies and designing integrated energy system solutions.

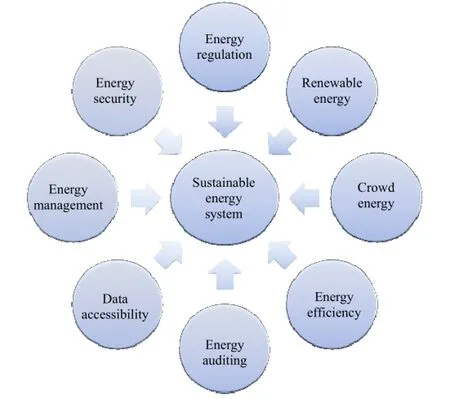

The core components of the sustainability development in energy system are summarized in Fig. 2, such as energy regulation, renewable energy sources, crowd energy/energy decentralization, energy security, energy management, energy efficiency, energy auditing, and reporting/data accessibility.

Fig. 2. Sustainable energy system components.

A. Energy Regulation

An energy policy is the manner by which a given entity (often governmental) has decided to address issues of energy development including energy production, distribution, and consumption. The attributes of the energy policies may include legislation, international treaties, incentives to investment, agreements, guidelines for energy conservation, taxation, energy efficiency standards, and energy guide labels[20]. The energy policies are used widely in the industrial sector to meet specific energy use or energy efficiency targets. An industrial energy policy can be viewed as a tool for developing a long-term strategic plan, covering a period of 5 years to 10 years, for increasing the industrial energy efficiency and reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This policy engages not only the engineers and management at industrial facilities, but also includes government, industry associations, financial institutions, and others[21]. There are many types of policies and programs that have been used in countries worldwide to improve energy efficiency in the industrial sector, e.g., regulations, standards, fiscal policies, agreements, and benchmarking.

B. Renewable Energy Sources

Renewable energy sources include solar, wind, hydro, geothermal, and biomass. All have been realized to a limited degree so far. This is a more realistic solution for the near future. Renewable energy is freely available and it is pollution-free, but at the present time it does not compete in economic terms with cheap fuels such as coal, oil, and gas. This is because, so far, the technology of harnessing renewable energy is relatively inefficient. However, considerable international efforts have been coordinated to increase the use of renewable energy in order to reduce theglobal warming caused by the combustion of fossil fuels[22]. Sustainable energy development strategies typically involve three major technological changes: Energy savings on the demand side, efficiency improvements in the energy production, and the replacement of fossil fuels by various sources of renewable energy. Consequently, large-scale renewable energy implementation plans must include strategies for integrating renewable sources in coherent energy systems influenced by energy savings and efficiency measures[7].

C. Crowd Energy/Energy Decentralization

Considering the progress of the industrial automation in terms of technical processes in the last few years, it seems to be logical to apply the developed knowledge, tools, and processes to the energy sector. This leads us to the crowd energy concept: Crowd energy is the collective effort of individuals or profit or non-profit organizations, or both, pooling their resources through online ICT applications to help to implement the energy turnaround. This implies both, the concept of decentralization (production, storage, and consumption of renewable electricity) and a substantial change in society, economy, and politics. Electricity storage is the innovation crystallization point. The information and communication technology will play an essential role in the future power grids[23].

D. Energy Security

Energy security is defined as the uninterrupted availability of energy sources at an affordable price. Energy security has many aspects. For example, long-term energy security mainly deals with timely investments to supply energy in line with economic developments and environmental needs. On the other hand, short-term energy security focuses on the ability of the energy system to react promptly to sudden changes in the supply-demand balance[24].

The enterprise architecture is now getting a fresh look as an approach for addressing specific IT problems, including enhancing agency cyber security defences. Government agencies will also need some glue codes to make the various tools work together, as the energy security issue in general and a highly multidisciplinary topic.

E. Energy Management

Nowadays energy management begins to be considered one of the main functions of industrial management. Even top management of the enterprises participates in planning various energy management projects on a regular basis. Energy management is the judicious and effective use of energy to maximise profits and to enhance competitive positions through organisational measures and optimisation of energy efficiency in the processes. It combines the knowledge and skills of engineering, management, and housekeeping. The energy management system establishes clear-cut responsibilities, documented procedures, ongoing training, internal checks for conformance, corrective and preventive actions, management reviews, and continual improvement[10]. The main objectives of energy management are to minimize the energy costs/wastes without affecting the productions and quality and to minimize the negative environmental effects.

F. Energy Efficiency

Energy efficiency is the main target of a sustainable development policy as energy efficiency improvement allows to save means and to reduce energy consumptions, energy import dependency, and GHG emissions from energy productions and consumptions. There are various possible energy efficiency improvements including the changes in production process, investment in researches and developments (R&D), and implementation of energy-saving technologies or energy management systems[25]. Energy efficiency also can be achieved by adjusting and optimizing energy using systems and procedures so as to reduce energy requirements per unit of output while holding constant or reducing total costs of producing the output from these systems. Improving energy efficiency may result in other benefits that outweigh the energy cost savings, including decreasing business uncertainties and reducing exposure to fluctuating energy costs, increasing product quality and switching to higher added value market segments, increasing productivity, and reducing environmental compliance cost such as greenhouse gases and criteria air pollutants[11].

G. Energy Auditing

The energy audit is the key for decision-making in the area of energy system development. It plays an important role in identifying energy saving possibilities of the enterprise. The energy audit is thus a reliable and systematic approach in the industrial sector. It helps an organization to analyze its energy use and discover areas where energy use can be reduced, also helps to identify all the energy streams in a facility and quantify energy usage[20]. Hence, the energy management approach can be one answer to reduce energy consumption and meet CO2emission mitigation obligations[22]. The energy audit requires a systematic approach-from the formation of a suitable team, to achieve and maintain energy savings. Benefits can be achieved through the energy audit[26]:

· Reduction in specific energy consumption and environmental pollution;

· Reduction in operating costs (approximately 20%-30%) by systematic analysis;

· Improving the overall performance of the total system, the profitability and productivity;

· Slowering the depletion of natural resources and narrowing the demand supply gap;

· Averting the equipment failure.

H. Reporting/Data Accessibility

Enterprises globally adopt sustainability initiatives, executives need tools to support the reporting and management of these initiatives. While sustainability reporting is mandatory in some countries, many business leaders are working to become more responsible in managing their energy and water usages, GHG emissions, and social and community programs. They are collecting and reporting this information to support internal improvement initiatives and to provide stakeholders a better sense of the impact an organization has on the environment and the regions in which it operates. The annual reports of the many companies should mention the details of energy conservation activities and various achievements by the companies regarding energy conservation projects[20]. Enterprises are looking for software solutions that can support a more easily repeatable process, while providing a higher level of quality and confidence in the data reported. This is particularly important if the data are subject to the external auditing and assurance. Technologies that support these activities should conform to global sustainability reporting guidelines, e.g., Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP).

Table 1: Sustainable energy system architectural properties[12]

Sustainable energy system architectural properties should be used to guide the architecting and design processes. It is difficult to define a generic energy system architecture that meets the needs of all enterprise architectures. However, it is important to develop an architecture that is adaptable, agile, and to meet the enterprise strategic objectives of evolving into a sustainable enterprise’s development. Table 1 lists and describes the critical energy system architectural properties that are important to guide the development of a sustainable energy system[12].

Fortunately many essential elements of a sustainable energy transition can be expected to mesh well with other critical development objectives, which have been analyzed in this section. The objective of the next section demonstrates how a strategic enterprise architecture driven approach could effectively guide the sustainable energy system development.

4. Enterprise Architecture for Sustainable Energy System Development

Since energy is an enabler for almost all efforts within a technology-driven business, redefining of how energy is to be generated, stored, managed, and distributed should be incorporated into the enterprise value streams. From powering lightings and computers to complex productions and communication equipments, the energy system is a core necessity to power electronic and mechanical devices which are relied upon the conduct of enterprise efforts. The development of the sustainable energy systems can be assisted by the enterprise architecture. Through the application of the enterprise architecture, the interrelations between the energy system and the other fields, such as processes, services, and knowledge, and the other supporting infrastructure components, such as facilities, communication networks, and IT networks, can be more easily understood and exploited to develop incentive to implement the enterprise transformation[12].

There are a number of frameworks that can be used to develop the enterprise architecture to support the sustainable energy system development such as Zachman[26], Department of Defense Architecture Framework (DoDAF)[27], The Open Group Architecture Framework (TOGAF)[17], Federal Enterprise Architecture Framework (FEAF)[28], and The Gill Framework[4], etc. The Zachman framework offers the architecture taxonomy. The DoDAF and FEAF focus on the government enterprise architecture implementation. TOGAF is an open generic framework that provides an architecture development method and guidelines for developing the business and information system (application and data) and technology architectures within the overall enterprise architecture context.

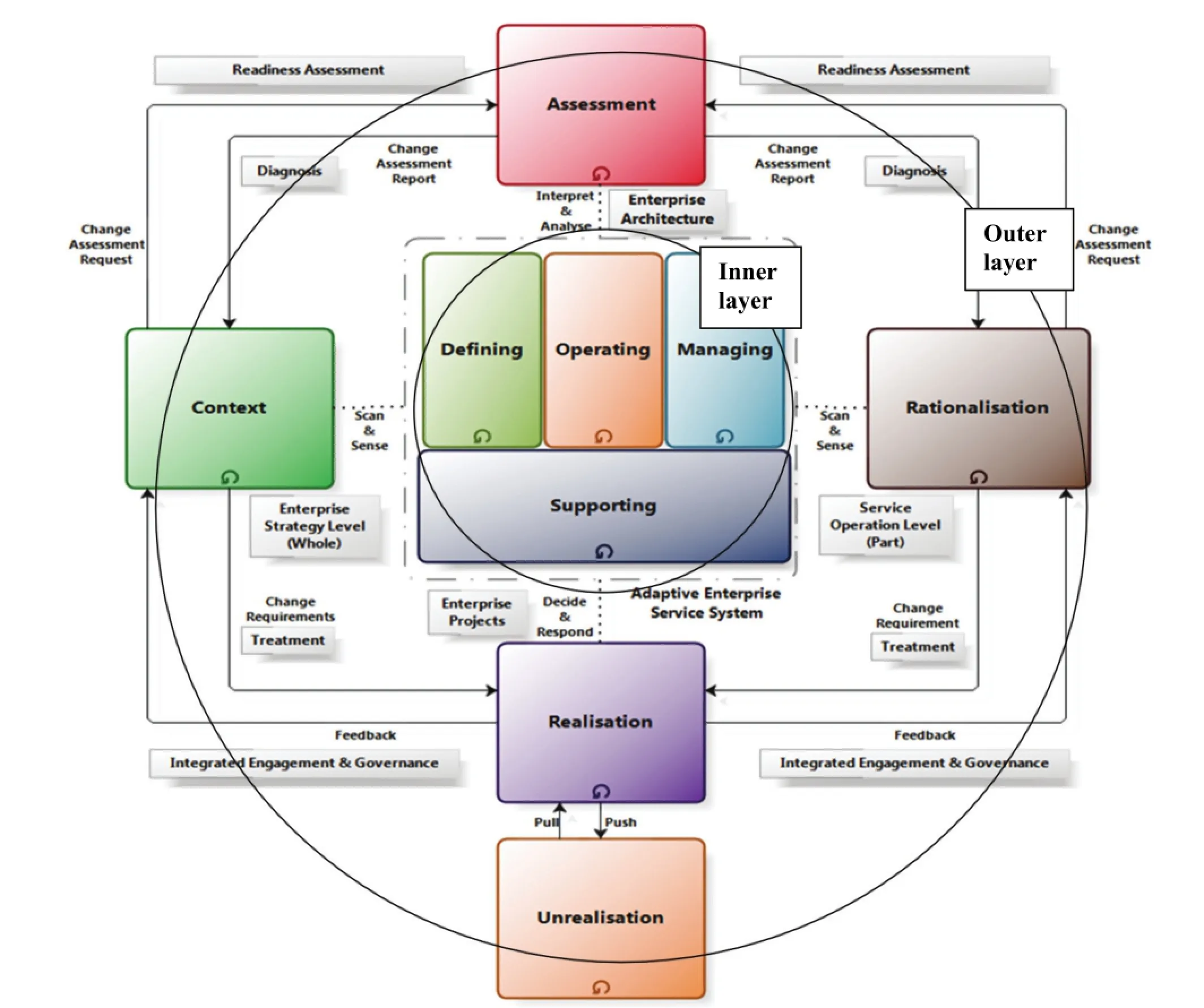

These frameworks are different in the nature and scope and are continuously evolving. It is unlikely that a single framework is able to be used or adopted off-the-shelf for any specific organisational context. Organisations need to tailor their local enterprise architecture frameworks by combiningelements from different frameworks that suit their specific needs. The challenge is which enterprise architecture framework(s) are appropriate and provide the necessary elements to develop the sustainable energy system architecture. It has been noticed that none of the above mentioned frameworks explicitly provide the support for developing the energy architecture. The Gill Framework is a meta-framework that provides an adaptive approach and energy architecture metamodel to define an adaptive enterprise architecture framework and capability for developing sustainable energy system architecture within the overall context of the agile or adaptive enterprise architecture. Therefore, we propose and discuss the use of The Gill Framework (see Fig. 3) for developing the sustainable energy system architecture. The Gill Framework is not another prescriptive enterprise architecture framework. It builds on the action-design research and adaptive enterprise service system theory[4]. The adaptive enterprise service system theory incorporates the living systems thinking[29],[30], agility[31], and service science[32]and defines an adaptive or agile enterprise as an adaptive enterprise service system (AESS). This framework provides an AESS lifecycle management approach and an AESS metamodel. The AESS lifecycle management approach can be used for adapting—A, defining—D, operating—O, managing—M, and supporting—S (a.k.a. ADOMS) the AESS architecture. The ADOMS approach is organised into two main layers (see Fig. 3): Outer layer and inner layer.

Fig. 3. The Gill Framework—ADOMS[4].

A. Outer Layer

The outer layer guides the continuous monitoring (context awareness), assessment, and adaptation of internal and external changes. The outer layer presents the following adapting stage services: Context, assessment, rationalisation, realisation, and unrealisation.

The context service continuously scans and senses (monitors) strategic changes at the holistic enterprise level.The rationalisation service continuously scans and senses the changes at the operational individual capability service level. The identified changes could be technological advancement, environmental performance, and economic growth concerns, etc. The assessment service interprets and analyses the impacts and root causes of the identified changes both at the enterprise and capability service level and produces the change assessment report with recommendations. The realisation service responds to the identified changes and may result in the initiation of one or more projects or program of works for developing or improving the energy system architecture to guide the energy system development.

B. Inner Layer

The inner layer realises the changes or requirements reported by the outer layer through defining, operating, managing, and supporting.

The defining stage or capability is focused on defining or tailoring an architecture method or framework by using the practices from existing well-known frameworks, such as TOGAF and Zachman, etc., in response to the identified changes or requirements. It defines the actors and roles (stakeholders), processes and tools for developing the energy system architecture. The operating stage is focused on the operating the defined capability. It engages actors and roles that execute processes, use tools, and iteratively produce energy system architecture. This involves developing and integrating all layers of the enterprise architecture such as social, business, information, application, and infrastructure layers and their integrations to describe the overall integrated energy system architecture. The energy system architecture is then used to guide the energy system development. The managing stage is focused on handling any changes in the architecture capability (e.g., processes, actors, roles, and tools) or in the energy system architecture itself through changing management processes. Finally, the adapting, defining, operating, and managing stages or capabilities are supported by the supporting capability which includes human resources and financial supports, etc. The ADOMS approach stages or capabilities are iteratively executed to evolve the energy system architecture in small increments, which is different from a big bang traditional upfront detailed architecture development approach.

Traditional big bang approaches focus too much on upfront detailed architecture documents and heavy processes, which have been criticized for not delivering a system or value early[33]. Therefore, the adaptive or agile ADOMS approach seems appropriate, in which energy system architecture details emerging as its implementation is progressed in short iterations. In this way, a high level architecture is developed at the start and low level details are emerged through the iteration implementation. The iterative implementation enables a feedback loop mechanism, e.g., plan, do, check, and adjust, and architecture is adjusted as the required in response to the feedback. This states the adaptive nature of the architecture through the ADOMS approach.

5. Conclusions

The sustainability phenomenon is fundamentally changing the way enterprises develop and operate different systems. The multidimensional sustainable energy system is one such system, which is difficult to develop due to the inherent complexity and involvement of various interrelated internal and external factors. Further, it is found that the energy system is a core enabler for technology-based business, and linked with the current focus on green and sustainable energy which provides a focal point for enterprises to leverage and initiate transformation efforts to align the energy infrastructure with larger enterprise strategic objectives. This paper highlighted that the sustainable energy system development requires a holistic and strategic approach. Also it was demonstrated how to use an agile enterprise architecture driven approach to handle the complex case of sustainable energy system development. One of the advantages of using the agile enterprise architecture driven approach is that it helps to iteratively design and integrate the different architecture layers, such as social, business, information, application, and infrastructure, to holistically define the components of the complex sustainable energy system and related influencing factors.

In future, we intend to further extend our research and present the details of each architecture layer relevant to describe the sustainable energy system design, which can then be used to guide its implementation.

[1] J. Vasauskaite and L. Gaspareniene, “The impact of EU energy policies on technological performance of Lithuanian manufacturing enterprises,” in Proc. of the 8th Intl. Scientific Conf. on Business and Management, Vilnius, 2014, pp. 612-619.

[2] H. P. Wallner, “Towards sustainable development of industry: Networking, complexity and eco-clusters,” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 49-58, 1999.

[3] S. C. Feng and C. B. Joung, “An overview of a proposed measurement infrastructure for sustainable manufacturing,”in Proc. of the 7th Global Conf. on Sustainable Manufacturing, Chennai, 2009, pp. 355-360.

[4] A. Q. Gill, Adaptive Cloud Enterprise Architecture, World Scientific Publisher, 2015.

[5] B. H. Roberts, “The application of industrial ecology principles and planning guidelines for the development of eco-industrial parks: An Australian case study,” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 12, no. 8, pp. 997-1010, 2004.

[6] T. Tsoutsos, M. Drandaki, N. Frantzeskaki, E. Iosifidis, and I. Kiosses, “Sustainable energy planning by using multi-criteria analysis application in the island of Crete,”Energy Policy, vol. 37, no. 5, pp. 1587-1600, 2009.

[7] H. Lund, “Renewable energy strategies for sustainable development,” Energy, vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 912-919, 2007.

[8] B. Swords, E. Coyle, and B. Norton, “An enterprise energy-information system,” Applied Energy, vol. 85, no. 1, pp. 61-69, 2008.

[9] A. Kolk and J. Pinkse, “Towards strategic stakeholder management? Integrating perspectives on sustainability challenges such as corporate responses to climate change,”Corporate Governance, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 370-378, 2007.

[10] R. Kannan and W. Boie, “Energy management practices in SME--case study of a bakery in Germany,” Energy Conversion and Management, vol. 44, no. 6, pp. 945-959, 2003.

[11] E. Worrell, P. Blinde, M. Neelis, E. Blomen, and E. Masanet, Energy Efficiency Improvement and Cost Saving Opportunities for the U.S. Iron and Steel Industry, University of California, 2010, ch. 7.

[12] A. C. Sheets, “Leveraging enterprise architecture to enable integrated test and evaluation sustainability,” Ph.D. dissertation, Engineering Systems Division, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambrige, MA, 2011.

[13] D. Gordic, M. Babic, N. Jovicic, V. Šušteršic, D. Koncalovic, and D. Jelic, “Development of energy management system -Case study of Serbian car manufacturer,” Energy Conversion and Management, vol. 51, no. 12, pp. 2783-2790, 2010.

[14] Defining Architecture, ISO/IEC/IEEE 42010,. 2007.

[15] M. Holgado, S. Evans, D. Vladimirova, and M. Yang, “An internal perspective of business model innovation in manufacturing companies,” in Proc. of the 17th IEEE Conf. on Business Informatics, 2015, pp. 9-16.

[16] A. Q. Gill, “Towards the development of an adaptive enterprise service system model,” in Proc. of the 9th ACMIS, Chicago, USA, 2013, pp. 1-9.

[17] R. Harrison, TOGAF Foundation, The Open Group, 2011.

[18] Business motivation model (BMM). OMG. 2014. [Online]. Available: http://www.omg.org/spec/BMM/

[19] B. Kultida, H. Sunil, C. Cordia, P. Tri Dung, and S. Jakkris,“The integration of occupational health and safety into the development of eco-industrial parks,” Health and the Environment Journal, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 72-84, 2015.

[20] E. A. Abdelaziz, R. Saidur, and S. Mekhilef, “A review on energy savings in industrial sector,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 15, pp. 150-168. Jan. 2011.

[21] J. Vasauskaite and D. Streimikiene, “Review of energy efficiency policies in Lithuania,” Transformations in Business & Economics, vol. 13, no. 3C, pp. 628-642, 2014.

[22] T. Al-Shemmeri, Energy Audits: A Workbook for Energy Management in Buildings, John Wiley & Sons, 2011, ch.10.

[23] S. Teufel and B. Teufel, “The crowd energy concept,” Journal of Electronic Science and Technology, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 570-578, Sep. 2014.

[24] T. Mather, S. Kumaraswamy, and S. Latif, Cloud Security and Privacy: An Enterprise Perspective on Risks and Compliance, O'Reilly Media Inc., 2009.

[25] A. J. D. Lambert and F. A. Boons, “Eco-industrial parks: Stimulating sustainable development in mixed industrial parks,” Technovation, vol. 22, no. 8, pp. 471-484, 2002.

[26] The Zachman Framework, The Official Concise Definition, Zachman Intl., 2008.

[27] DoDAF. The DoDAF architecture framework. (2010). [Online]. Available: http://dodcio.defense.gov/TodayinCIO/ DoDArchitectureFramework.aspx

[28] Federal enterprise architecture. FEAF. (2013). [Online]. Available: https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/e-gov/fea

[29] M. W. Maier, “Architecting principles for systems-of-systems,” Syst. Engin., vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 267-284, 1998.

[30] J. G. Miller, Living Systems, University Press of Colorado, 1995.

[31] A. Q. Gill and B. Henderson-Sellers, “An evaluation of the degree of agility in six agile methods and its applicability for method engineering,” Journal of Information and Software Technology, vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 280-295, 2008.

[32] J. Spohrer and S. K. Kwan, “Service science, management, engineering, and design (SSMED): An emerging discipline—outline & references,” Intl. Journal of Information Systems in the Service Sector, vol. 1, no. 3, pp.1-31, 2009.

[33] A. Q. Gill and M. A. Qureshi, “Adaptive enterprise architecture modelling,” Journal of Software, vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 628-638, May 2015.

Jovita Vasauskaiteis an associated professor at Kaunas University of Technology, holding the Ph.D degree in economics. sShe has worked as a postdoctoral fellow with Lithuanian Energy Institute. She has experience in the projects related to corporate social and environmental responsibility and entrepreneurial competence. Her main research fields are new

technology implementation, energy efficiency development in industry, and sustainability development.

Asif Qumer Gillis a TOGAF 9 Certified Enterprise Architect, lecturer, and researcher with the School of Software, University of Technology, Sydney. He specializes in software-intensive agile enterprise architecture and engineering practices, tools, and techniques. He is an experienced author, coach, consultant, educator, researcher, speaker, trainer, and thought leader. He has extensive experience in both agile and non-agile, cloud and non-cloud complex software development environments.

Manuscript received May 15, 2015; revised July 21, 2015.

J. Vasauskaite is with Kaunas University of Technology, Kaunas 44249, Lithuania (Corresponding author e-mail: jovita.vasauskaite@ktu.lt).

A. Q. Gillis with University of Technology Sydney, Sydney PO Box 123, Australia (e-mail: Asif.Gill@uts.edu.au).

Digital Object Identifier: 10.11989/JEST.1674-862X.505151

Journal of Electronic Science and Technology2015年3期

Journal of Electronic Science and Technology2015年3期

- Journal of Electronic Science and Technology的其它文章

- Energy Management Strategies for Modern Electric Vehicles Using MATLAB/Simulink

- Hybrid Aging Delay Model Considering the PBTI and TDDB

- Time-Efficient Identification Method for Aging Critical Gates Considering Topological Connection

- Residual Phase Noise and Time Jitters of Single-Chip Digital Frequency Dividers

- A Methodology to Measure the Environmental Impact of ICT Operating Systems across Different Device Platforms

- Enhancement of Distributed Generation by Using Custom Power Device