Multiperspective Analysis of Microscale Trigeneration Systems and Their Role in the Crowd Energy Concept

Parantapa Sawant, Naim Meftah, and Jens Pfafferott

Multiperspective Analysis of Microscale Trigeneration S

ystems and Their Role in the Crowd Energy Concept

Parantapa Sawant, Naim Meftah, and Jens Pfafferott

—The energy system of the future will transform from the current centralised fossil based to a decentralised, clean, highly efficient, and intelligent network. This transformation will require innovative technologies and ideas like trigeneration and the crowd energy concept to pave the way ahead. Even though trigeneration systems are extremely energy efficient and can play a vital role in the energy system, turning around their deployment is hindered by various barriers. These barriers are theoretically analysed in a multiperspective approach and the role decentralised trigeneration systems can play in the crowd energy concept is highlighted. It is derived from an initial literature research that a multiperspective (technological, energy-economic, and user) analysis is necessary for realising the potential of trigeneration systems in a decentralised grid. And to experimentally quantify these issues we are setting up a microscale trigeneration lab at our institute and the motivation for this lab is also briefly introduced.

Index Terms—Adsorption cooling, decentralisation, energy efficiency, energy system analysis, trigeneration.

1. Introduction/Methodology

Energy efficient power conversion and transmission is the transitional bridgeway to a secure and sustainable energy future. Energy efficiency encompasses the entire value chain from the conversion of primary energy to final energy and its distribution and consumption. Thus various fields of science and engineering are involved in the pursuit of higher energy efficiency in different sectors by using innovative ideas, methodologies, processes, and technologies.

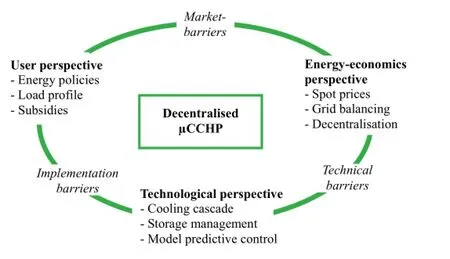

A trigeneration system or a combined cooling, heating, and power (CCHP) system is one such highly efficient primary energy (PE) conversion technology for the power sector[1]. However, its deployment is hindered due to multiple interdisciplinary barriers and accordingly a multiperspective research is necessary to develop possible solutions for making the technology more market-friendly[2]-[4].The barriers and different research perspectives are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Multiperspective analysis of decentralised µCCHP system.

From the operators point of view, questions regarding subsidies on equipment, payback period, energy market, and the policy framework need to be analysed. From the energy-economic perspective, additional aspects on balancing of a decentralised smart grid, system integration of renewable energies, interoperability between gas and electricity grids, and also the heat and electricity market are of importance. System integration, standardisation of the control and operating strategies, and efficiency improvement are technological topics still under discussion.

To analyse these different perspectives for improving the market entry potential of trigeneration systems, further experimental and numerical research is necessary.

This paper takes a theoretical approach for highlighting the research perspectives necessary to overcome the existing barriers for deployment of this technology. Additionally the potential of decentralized adsorption cooled microscale trigeneration systems in the “crowdenergy concept”[5](developed at the International Institute of Management in Technology (iimt), University of Fribourg) is also discussed.

In the next section of this paper the technological perspective and resulting research topics are described. The test rig we are building to pursue these research topics under the project “µGREETS- Micro Grid Reactive Energy Efficient Trigeneration Systems” is also briefly introduced.

The third section covers the initial theoretical analysis of the energy-economic perspective of such a system revealing its potential regarding the crowd energy concept in terms of the technical flexibility of a power system.

The fourth section develops on the technological and energy-economic perspectives to further highlight the user perspective and implementation barriers of trigeneration systems.

2. Technological Perspective

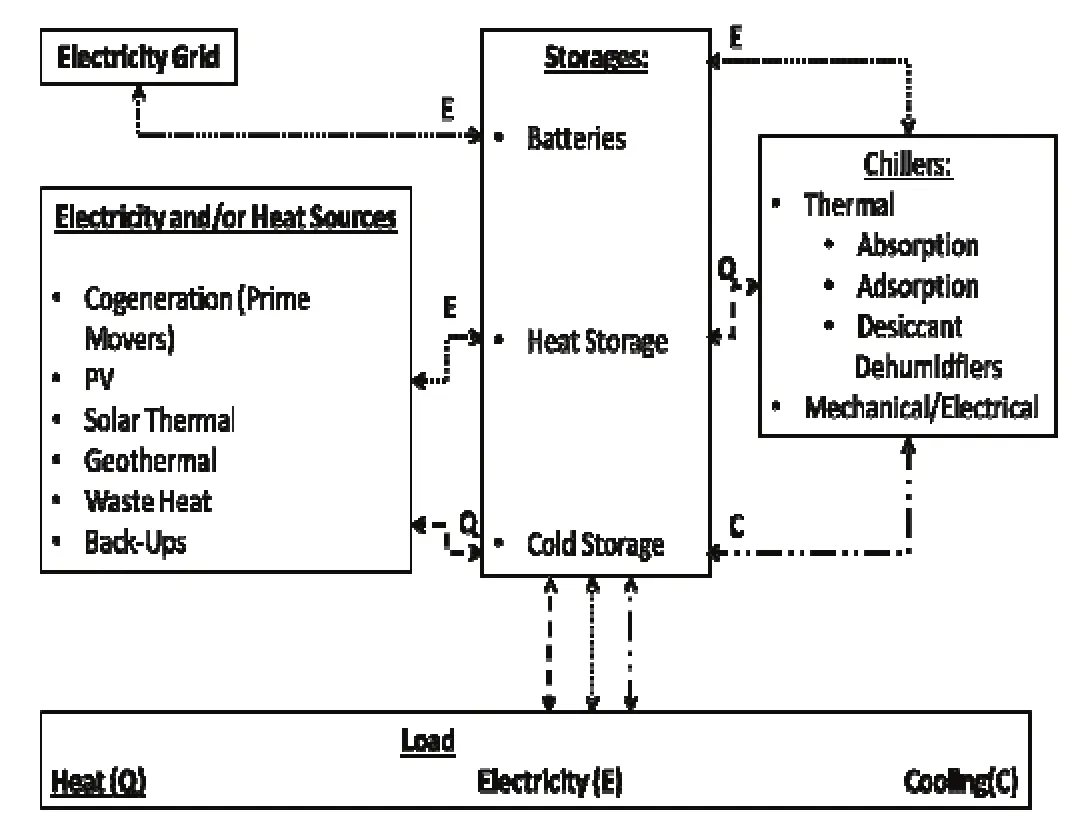

The general setup of trigeneration systems is shown in Fig. 2. The electricity grid and primary energy converters interact with their respective storages by transferring electricity (E) and heat (Q). This electricity and heat is used in the chilling section to produce cooling energy (C).

Fig. 2. Typical trigeneration set-up for smart buildings.

The system components interact based on the demand profile of the load section. Trigeneration plants are classified based on the components installed in each section and their capacities[6]-[8]. The primary energy converters could be conventional prime movers or renewable energy based systems. The prime movers could be further classified on the basis of fuel or technology used (biogas, natural gas, fuel oil engines or Stirling engines or fuel cells). The chillers are divided into thermal or mechanical chillers. Traditionally small to medium scale absorption chillers have been the backbone of the thermal chiller industry for decades by utilising high temperature waste heat from industrial processes or from power plants. They exhibit 90% primary energy conversion efficiency[9]. However, adsorption chillers are now slowly entering the market, especially for micro and small scale applications. This is because of their capability to work with low temperature waste heat (<95°C)[10]. This makes it an attractive technology to be clubbed with renewable energy or cogeneration (combined heat and power (CHP)) systems.

With the advent of micro scale prime movers, more efficient renewable energy heat sources cogeneration systems have become more compact and apt for decentralised solutions. This is also paving the path for trigeneration systems on the microscale (<20 kWel). Moreover, microscale trigeneration systems promise even greater flexibility and possibilities for demand side management in industrial, residential, educational or market complexes.

The technology to produce chilled water using heat as process energy for thermal chillers is now a mature technology[11]. Also the other individual components such as mechanical chillers, thermal storages, CHP units, and cooling towers are readily available. However, the technical barriers for the deployment of this technology exist and need to be solved. These barriers comprise of issues related to selection and design of components, plant processes, system integration and control strategies, comparison to other technologies, and standardisation of operational strategies for different possible configurations[12],[13].

2.1 Overcoming the Technical Barriers

Many different system configurations are possible for a trigeneration system and since three different power sources (electricity, heating, and cooling) are to be managed, the interdependency of the components is very complex. Stable engineering designed to handle different operating modes and robust control strategies are necessary to make this technology more market-friendly.

To achieve these factors, extensive field research on real life test rigs is the need of the hour. However, most of the research is focussing on the improvement of the adsorption cycle, the power density, and the adsorbent material itself. In order to understand the technical challenges and potential of this technology, system level studies are necessary.

Additionally theoretical and experimental research on the component level has shown the potential for improving the efficiency of the system through innovative concepts, such as cooling cascading, balancing the fluctuating temperatures of adsorption cycle using stratified storages[14]and storage management. These ideas and methods must also be integrated in test rigs simulation that is close to reality situations to obtain an insight into the various control strategies and engineering design of such systems.

Although some field tests exist but research projects focussing on high level control and system integration arestill inadequate[15]-[17]. Also, each configuration is different from another and the research focus also differs. Thus no benchmarking is yet possible.

In order to pursue experimental research that is complimentary to the existing theoretical and practical developments, we are setting up a test rig at the Institute for Energy System Technologies (INES) in Offenburg for a micro scale trigeneration system based on adsorption cooling.

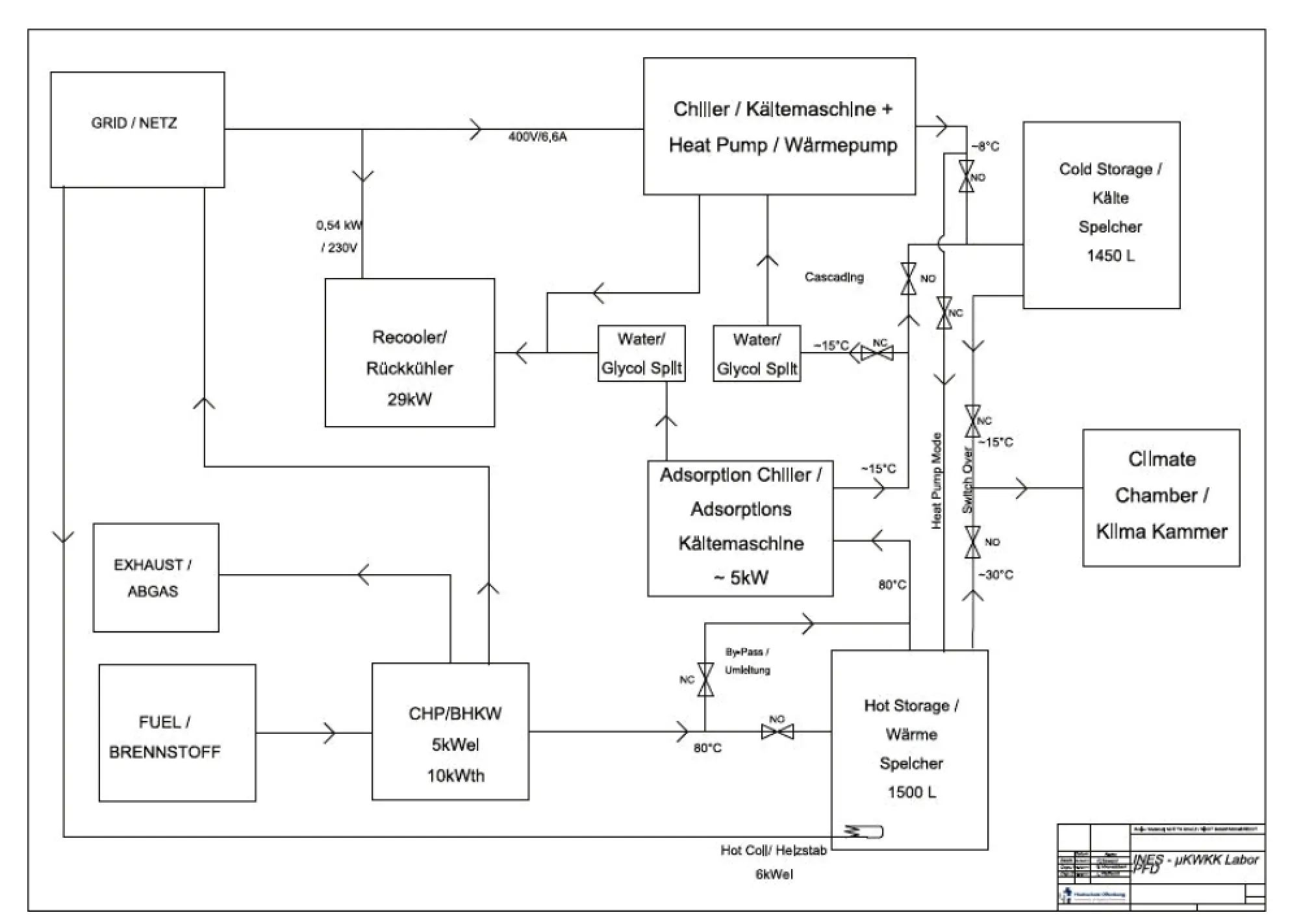

A process flow diagram for the test rig is shown in Fig. 3. A real life CHP machine is being used and will give us the chance to analyse its behaviour under different operational conditions. An adsorption chiller will serve as a low temperature thermal chilling device. For comparing with other technologies, a conventional mechanical chiller will also be integrated into the system. The adsorption chiller will be cascaded with the mechanical chiller to provide the step cooling cascading effect in an attempt to increase overall efficiency of the system. A water cooled recooler will act as the heat sink for the chilling units and thus we will gather experience for planning and operation of such systems.

To completely tap the potential of trigeneration systems, thermal storages play a central role. Storage management will help to optimize the energy of the system and also achieve better CHP runtime and thermal comfort. The thermal storages will be connected to the INES climate chamber in a heating or cooling switch-over mode.

The climate chamber will act as a smart building load with concrete core activation. A novel non-linear model predictive control (NLMPC) algorithm for optimising the operational capability of a microscale trigeneration system based on thermal storage management will be developed. This algorithm will include statistical references and integrated system parameters, and provide control strategy for a trigeneration system that is integrated into smart buildings.

Unfortunately, overcoming only the technological barriers is not enough to capitalise on this technology and thus the energy-economic perspective must also be covered.

3. Energy-Economics Perspective

Literature research to assess the energy-economic perspective of trigeneration systems has pointed out the many benefits of these systems in terms of increased fuel efficiency, emissions reduction, usage of local resources, and the potential role they can play as a decentralized energy source in the crowd energy concept[18].

Fig. 3. Process flow diagram for the test facility at INES, Offenburg University of Applied Sciences.

However an all-inclusive analysis of trigeneration applications from this perspective is a complex issue to address. The profitability is influenced by various factors for example, plant configuration, operational strategies, and external variables, such as energy prices and energy policies.

The market entry of these technologies is still plagued by negative perception of thermal chillers and economic comparison with grid electricity for mechanical chilling. Also, many cogeneration planners and installers focus on heating only operations of their units.

Factors such as fluctuating fuel prices, energy security, and flexibility in a grid need to be incorporated in the techno-commercial analysis of such systems to comprehend their overall advantages. This is the link between trigeneration systems and the crowd energy concept.

This concept was promptly introduced by Stephanie Teufel and Bernd Teufel in their position paper aptly titled“The Crowd Energy Concept”. The idea extensively involves management of resources utilising information and communication technology. Individuals or organizations manage resource pools with the common goal of energy security for everyone at the cheapest possible price. Inevitably, this brings the need for decentralised energy conversion and storage, and the participation of people from the socio-political perspective.

The concept of a “prosumer” coined by Alvin Toffler[19]is extrapolated to an energy prosumer in the crowd energy concept. The energy prosumer is compared to an intelligent cell or block capable of generating-storing-loading energy. A network based on crowd energy would presumably involve many such cells eventually forming a crowd. Decentralisation would play a very important role in such a energy cell/block based network and tools for demand response and energy storage would be key.

3.1 Overcoming the Market Barriers

For the decentralisation concept to be realized in the practical and technical sense, the flexibility of a system to incorporate variable renewable energies is very important. As described in International Energy Agency’s “Harnessing Variable Renewables—A Guide to the Balancing Challenge”[20], if a power system aims to integrate more renewable, it should have enough flexibility/capability to modify electricity production and consumption in response to any expected or unexpected variability. Fig. 4 gives an overview of such a relationship.

The flexibility of a system measured as units of electricity that could be ramped up or down in a minute is achievable through dispatchable and decentralised power plants, such as a trigeneration plant with thermal storages. As discussed in the earlier section of this paper a microscale trigeneration system fits the requirements of a decentralised cell defined in the crowd energy concept. Utilising the intelligence of the thermal storages such systems can help in shaving off peak heating and cooling loads.

Another factor, through which decentralised trigeneration systems support the crowd energy concept, is through their potential to supply energy reliably. Such disperse and flexible systems are relatively independent from grid malfunctions and other natural or human disruptions. This reliability should be qualitatively analysed in the crowd energy research projects to improve the energy-economic perspective of trigeneration.

Fig. 4. Variability flexibility relationship in a power system.

A system that includes many on-site trigeneration plants operated with renewable energies such as photovoltaics and biogas can also provide an added advantage of geographical spread. This reduces the impact of variance in renewable energy supply within a localised geographical area. Since the dimensions of these systems are smaller, it is easier to choose between different sources of primary energy. And thus the capacity of a prosumer to react to grid fluctuations increases.

The crowd energy concept can tap the immense potential of decentralised trigeneration systems and in turn support these technologies to overcome their market barriers.

However, the flexibility and decentralisation of systems comes at the price of high level automation, control, and information transfer. To achieve the maximum possible benefits of microscale trigeneration in the crowd energy concept, a techno-commercial optimisation of the system isnecessary. The optimisation algorithm should be able to interact with the grids considering spot prices for the gas and electricity market, heating and cooling costs, and weather forecasts.

4. User Perspective

Energy efficiency and rentability are the main driving forces for the installation of trigeneration systems. Energy costs (yearly) can be easily calculated based on an energy flow diagram. Considering monetized benefits from grid integration and self-sufficiency such as that in crowd energy concepts, the overall system may become economically feasible.

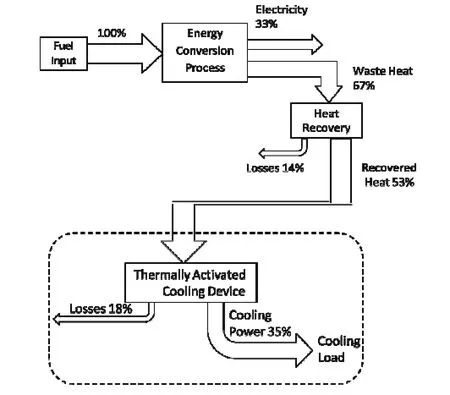

From the implementation perspective, trigeneration systems are a technical extension of cogeneration systems to increase overall efficiency and to achieve longer operating periods[21]as shown in Fig. 5. Over the summer months the waste heat overflow from the cogeneration units is converted to cooling load using thermal chillers.

Fig. 5. Simplified Sankey diagram for trigeneration.

The implementation barriers result from the influence of the factors that create the technological and the market barriers for this system.

4.1 Overcoming the Implementation Barriers

Day-to-day practice cogeneration systems are frequently planned but rarely realised. There are many reasons for the poor market dissemination. Though many systems may be operated profitably, the high investment costs and complex operation strategy are main barriers. These issues manifest themselves also to the case of trigeneration systems.

Planners must develop implementation strategies for user specific demand side load profiles for heating, cooling, and electricity. This involves deeper analysis and need for standardisation. The possibility to benefit from energy policies regarding feed-in tariffs and usage of biogas or grid balancing should also be analysed at least in a qualitative manner. Weighting and scoring methods could be a possible approach to signify the importance of grid integration parameters.

5. Conclusions/Research Focus

This paper summarised the findings of the initial literature research for the microscale trigeneration project at the Institute of Energy System Technologies in Offenburg. The findings were expressed in a multiperspective approach. The potential of trigeneration systems as a decentralised, energy efficient, flexible, and environment friendly transitional bridgeway to a secure energy future was established. Innovative ideas such as crowd energy concepts to propagate renewables and decentralisation can benefit from trigeneration systems under favourable technological and energy-economic parameters.

The motivation to setup an experimental lab for techno-commercial analysis of a real life test rig was explained. In the first phase of the project a test bench will be commissioned. Experiments will be run utilising stratified thermal storages, a state of the art adsorption chiller, and a cooling cascade. Corresponding results will be used for system modelling and analysis. In the next phase, operating strategies would be designed to achieve higher overall efficiency of the system.

To realise the true potential of trigeneration systems, our future research focuses will be to achieve technological enhancements in storage management, system integration and control as pointed out in this theoretical study. Energy-economic analysis for quantifying the benefits of trigeneration systems in terms of flexibility, demand side management and decentralisation will be done. Such developments will open new doors to increase market acceptance of trigeneration systems.

[1] D.-W. Wu and R.-Z. Wang, “Combined cooling, heating and power: A review,” Progress in Energy and Combustion Science, vol. 32, pp. 459-495, Aug. 2006.

[2] X.-Q. Kong, R.-Z. Wang, J.-Y. Wu, X.-H. Huang, Y. Huangfu, D.-W. Wu, and Y.-X. Xu, “Experimental investigation of a micro-combined cooling, heating and power system driven by a gas engine,” Intl. Journal of Refrigeration, vol. 28, pp. 977-987, Jul. 2005.

[3] G. Badea, “Microgeneration outlook”, in Design for Micro-Combined Cooling, Heating and Power Systems: Stirling Engines and Renewable Power Systems, 1st ed. vol. 1, N. Badea, Ed. Romania: Springer, 2014, pp. 1-29.

[4] N. Petchers, Combined Heating, Cooling & Power Handbook: Technologies & Applications: An Integrated Approach to Energy Resource Optimization, Lilburn: TheFairmont Press Inc., 2003, ch.3.

[5] S. Teufel and B. Teufel, “The crowd energy concept,”Journal of Electronic Science and Technology, vol. 12, pp. 263-269, Oct. 2014.

[6] U. Jakob, “Solare Klimatisierung und Kaelteerzeugung aus Sicht eines Systemanbieters”, presented at the DBU Workshop, Isnabrueck, Germany, Dec. 2-3, 2008. (in Germany)

[7] S. Li and J.-Y. Wu, “Theoretical research of a silica gel-water adsorption chiller in a micro combined cooling, heating and power (CCHP) system,” Applied Energy, vol. 86, pp. 958-967, Nov. 2008.

[8] K. C. Kavvadias, A. P. Tosios, and Z. B. Maroulis, “Design of a combined heating, cooling and power system: Sizing, operation strategy selection and parametric analysis,”Energy Conversion and Management, vol. 51, pp. 833-845, Nov. 2009.

[9] X.-Q. Kong, R.-Z. Wang, Y. Li, and J.-Y. Wu. (June 2010). Performance research of a micro-CCHP system with adsorption chiller. Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University (Science). [Online]. 15(6). pp. 671-675. Available: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12204-010-1067-2

[10] D.-C. Wang, Y.-H. Li, D. Li, Y.-Z. Xia, and J.-P. Zhang, “A review on adsorption refrigeration technology and adsorption deterioration in physical adsorption systems,”Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 14, pp 344-353, Aug. 2010.

[11] T. Núñez, “Thermally driven cooling: Technologies, developments and applications,” Journal of Sustainable Energy, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 16-24, 2010.

[12] E. Cardona, A. Piacentino, and F. Cardona, “Energy saving in airports by trigeneration. Part I: Assessing economic and technical potential,” Applied Thermal Engineering, vol. 26, no. 14-15, pp. 1427-1436, Oct. 2006.

[13] E. Cardona, A. Piacentino, and F. Cardona, “Energy saving in airports by trigeneration, Part II: Short and long term planning for the malpensa 2000 CHCP plant,” Applied Thermal Engineering, vol. 26, no. 14-15, pp. 1437-1447, Oct. 2006.

[14] H. Taheri, “Numerical investigation of stratified thermal storage tank applied in adsorption heat pump,” Ph.D. dissertation, Dept. Mech. Eng., Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Karlsruhe, Germany, 2014.

[15] M. Becker, B. Anders, K. Sturm T. Patel, and J. Braun,“Regenerativly operated and innovative combined-coolingheating and power system,” in Results of the Research Group Energy Efficient Technologies and Applications, W. Mayer, Ed. Goschy, Munich: Verlag Attenkofer, 2013, ch. G, pp. G1-G26.

[16] M. Jradi and S. Riffat, “Tri-generation systems: Energy policies, prime movers, cooling technologies, configurations and operation strategies,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 32, pp. 396-415, Feb. 2014.

[18] T. Kerr, Cogeneration and District Energy: Sustainable Energy Technologies for Today and Tomorrow, Paris: OECD/IEA, 2009, ch.1.

[19] A. Toffler, The Third Wave: The Classic Study of Tomorrow, New York: Bantam Books, 1980, ch. 4.

[20] H. Chandler, Harnessing Variable Renewables: A Guide to the Balancing Challenge, Paris: OECD/IEA, 2011, ch.3.

[21] S. Borg, “Micro-trigeneration for energy-efficient residential buildings in southern Europe” Ph.D. dissertation, Dept. Mech. & Aerospace Eng., University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, Scotland, 2012.

Parantapa Sawantwas born in Maharashtra, India in 1987. He received the B.E. degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Pune, India in 2009 and the M.Sc. degree from the University of Applied Sciences, Offenburg, Germany in 2011, in energy conversion and management. He is currently pursuing the Ph.D. degree at the Institute of Energy System Technologies, Offenburg University of Applied Sciences, Offenburg. His research interests include CCHP, adsorption cooling, energy system analysis, and model predictive control.

Naim Meftahwas born in Freiburg, Germany in 1991. He has been studying Energiesystemtechnik at the University of Applied Sciences, Offenburg since 2013. Presently he works at the Institute of Energy System Technologies, Offenburg University of Applied

Sciences,

Offenburg.

Hisarea

of responsibility is the construction of the trigeneration plant.

Jens Pfafferottis a professor at Offenburg University of Applied Sciences. He is supervising the MicroKWKK (MicroCCHP) research project and is vice-head of the Institute for Energy System Technologies at Offenburg.

(Jens Pfafferott’s photograph is not available at the time of publication.)

Manuscript received May 3, 2015; revised July 30, 2015. This work was supported by the “Industry on Campus” at HS Offenburg and by the Baden-Württemberg Ministry of Science, Research and Arts (MWK) under the “DENE” Project.

P. Sawant is with the Institute of Energy System Technologies, Offenburg University of Applies Sciences, Offenburg 77654, Germany (Corresponding author e-mail: parantapa.sawant@hs-offenburg.de).

N. Meftah and J. Pfafferott are with the Department of Mechanical and Process Engineering, Offenburg University of Applied Sciences, 77654 Offenburg (e-mail: naim.meftah@stud.hs-offenburg.de; jens.pfafferott@ hs-offenburg.de).

Digital Object Identifier: 10.11989/JEST.1674-862X.505031

Journal of Electronic Science and Technology2015年3期

Journal of Electronic Science and Technology2015年3期

- Journal of Electronic Science and Technology的其它文章

- Energy Management Strategies for Modern Electric Vehicles Using MATLAB/Simulink

- Hybrid Aging Delay Model Considering the PBTI and TDDB

- Time-Efficient Identification Method for Aging Critical Gates Considering Topological Connection

- Residual Phase Noise and Time Jitters of Single-Chip Digital Frequency Dividers

- A Methodology to Measure the Environmental Impact of ICT Operating Systems across Different Device Platforms

- Enhancement of Distributed Generation by Using Custom Power Device