祁连山鸡类物种多样性及其成因

文陇英

西南山地濒危鸟类保护重点实验室, 乐山师范学院生命科学学院, 乐山 614000

祁连山鸡类物种多样性及其成因

文陇英*

西南山地濒危鸟类保护重点实验室, 乐山师范学院生命科学学院, 乐山 614000

青藏高原祁连山孕育了丰富的鸡类物种多样性,有2科11种5个亚种,是我国鸡类分布中心之一,也是珍稀特有物种分布中心之一。祁连山鸡类多样性的成因主要有以下几方面:悠长的进化时间产生新的分类阶元;残存分布和迁入定居丰富了祁连山鸡类多样性;环境空间异质性,为不同生境要求的鸡类提供了适宜生境和可利用的生态位,以及鸡类生态位分化维持了祁连山鸡类的多样性;已建自然保护区为祁连山鸡类多样性提供了良好保护。

祁连山; 鸡类; 物种多样性; 残存分布; 迁入定居; 环境空间异质性

祁连山位于青藏高原东北缘,由多条西北—东南走向的平行山脉和宽谷组成,平均海拔4000 m以上,因位于河西走廊南侧,又名南山。西端以党金山口与阿尔金山脉相接;东端至黄河谷地,与秦岭、六盘山相连,是亚洲中部著名的高大山系之一。祁连山是相当古老的山脉,是青藏高原最早脱离海浸的地区,这里曾生活着白垩纪的鸟类[1]。祁连山以其漫长的进化史、特殊的生境和地理位置孕育了丰富的鸡类物种多样性,是我国鸡类分布中心之一[2],也是我国特有鸟类分布中心之一[3]。地球上物种多样性分布并不均匀,这一现象一直吸引着生物地理学家和生态学家,他们从时间、空间、气候、竞争、捕食和生产力等方面提出了多种假说,但至今没有统一解释[2]。祁连山鸡类研究经历了19世纪的标本收集和物种命名;20世纪的资源考察、区系和生态研究[2,4-7];进入21世纪以来,分子系统地理学研究为生物多样性研究提供了新的信息。国内外科学家在青藏高原和祁连山的地学、环境科学、冰川、植被和古动植物学等领域的研究成果颇多,为探讨祁连山鸡类多样性成因提供了交叉学科信息。

本文以青藏高原祁连山鸡类物种多样性为研究对象,以高原抬升、第三纪晚期和第四纪环境演变为背景,综述以往的研究成果,探讨祁连山鸡类多样性及其成因,希望在理论上能为生物多样性研究有所補益。

1 祁连山鸡类物种多样性、分布及特点

1.1 多样性

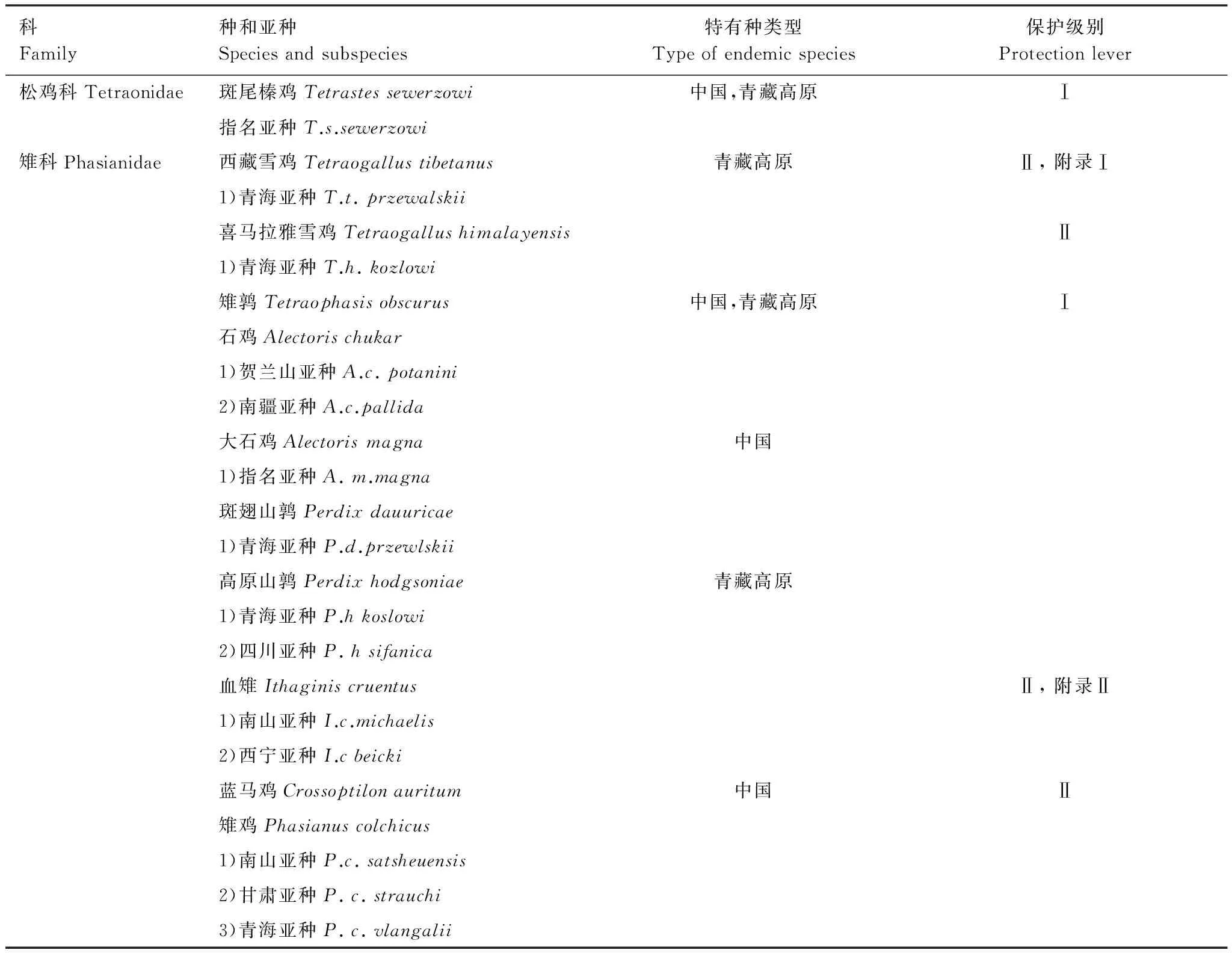

祁连山栖息着鸡类2科11种,具有我国全部的鸡类科级阶元(表1)。

1.2 亚种分化及其分布规律

11种鸡类中9种是多型种,在祁连山分布2个亚种以上的有4个种:石鸡、高原山鹑、血雉和雉鸡。其中雉鸡有3个亚种分布于祁连山;石鸡2个亚种中A.c.pallida分布于干旱的祁连山西段,而A.c.potanini则分布于较湿润的东段[8];高原山鹑的2个亚种中P.h.koslowi分布于甘肃张掖马蹄寺以西的祁连山南坡,而P.h.sifanica则分布于祁连山的东端,由此经甘肃和青海交界的山地向南分布到四川、西藏,该亚种更喜好湿润环境;血雉2个亚种中I.c.michaelis分布于祁连山的北坡,而I.c.beicki则分布于南坡[8];雉鸡3个亚种中P.c.satsheuensis分布于祁连山西部低山带,P.c.vlangalii分布于干旱的西段南坡,而P.c.strauchi则分布于较湿润的东段[8]。分布规律是每个种各有一个亚种分别分布于祁连山东段和西段,或者南坡和北坡,地理上相互替代。

2 鸡类物种多样性形成及维持机制

2.1 漫长的进化历史和冰期避难地

决定生物多样性的主要原因之一是需要漫长的进化历史。据祁连山鸡类分子系统进化研究,其分子钟标记的物种分化时间是晚第三纪和早更新世[9-13]。上新世祁连山生活着森林型和森林-草原型三趾马动物群,当时气候温暖[14],海拔高度约1330 m,青藏运动结束时上升到3000 m[15],到晚更新世末期接近现今的高度。中更新世晚期,大约0.45 Ma—0.47 Ma进入青藏高原冰冻圈,祁连山地区出现最早的冰期作用[16],雪线下移1400—1650 m[17-18]。之后祁连山虽然经历了几次冰期,但是冰川规模越来越小,冰期的雪线不断迁升[19],几乎没有发生山谷冰川[20],这给一些鸟类进化提供了充分的时间和空间。大石鸡起源于柴达木盆地干旱的祁连山南麓[21],斑翅山鹑也起源于祁连山[22,12]。漫长的进化时间,新的分类阶元丰富了祁连山鸡类多样性。

表1 祁连山鸡类种及亚种的特点

中更新世冰期祁连山地区还是一些鸟类的避难地[23-25],隔离分化形成不同亚种。祁连山血雉的两个亚种都是该山所特有,I.c.beicki分布于祁连山的南坡,而I.c.michaelis分布于祁连山的北坡[8],说明更新世冰期它们的祖先种群分别被隔离在祁连山南坡和北坡的避难地(森林),分化形成祁连山的两个特有亚种。高原山鹑青海亚种也为祁连山所特有[8],起源于祁连山;斑翅山鹑的P.d.przewlskii虽不是祁连山特有,但也起源于祁连山[12]。

2.2 残存和迁入

第三纪晚期和早更新世青藏高原生长着阔叶林、针阔混交林和针叶林[26],蓝马鸡、雉鹑、雉鸡和血雉几种森林鸡类的祖先种群可能广泛分布在高原山地的森林中,随高原抬升和第四纪冰期作用,森林型鸡类随森林逐渐退出高原面。祁连山东段受东亚季风影响,湿润气流被带到这里,形成多降水带,因此在海拔2500—3300 m有寒温性针叶林[18],使得高原土著森林鸡类残存于祁连山。斑尾榛鸡祖先种群在第四纪冰期从欧亚大陆北部南迁到青藏高原的寒温性针叶林,隔离进化成斑尾榛鸡[6],分子钟标定的时间[17]进一步为此提供了佐证。类似斑尾榛鸡的鸟还有黑啄木鸟(Dryocopusmartius)、三趾啄木鸟(Picoidestridactylus)、鬼鴞(Aegoliusfunereus)和黑头噪鸦(Perisoreusinternigrans)等[27]。

中更新世以来,青藏高原抬升和冰期干旱寒冷气候使高山灌丛草甸和荒漠草原得以发展,高山顶部发育了高山亚冰雪稀疏植被[28],适于草原型鸡类生存。起源于不同地区的西藏雪鸡、喜马拉雅雪鸡、石鸡和高原山鹑种群从不同的方向迁入到祁连山定居[29-30,12],丰富了祁连山鸡类多样性。

2.3 环境空间异质性和生态位分化

第三纪晚期以来祁连山快速抬升,到晚更新世,东段冷龙岭平均海拔4860 m,西段高山海拔达到5300—5600 m,从而形成了气候垂直带,包括暖温带、温带、寒温带和寒带,海拔5000 m以上的高山终年积雪不化。高原抬升影响了季风气流,形成祁连山东部湿润、西部干旱的气候格局。受地形、气候垂直和水平格局影响,祁连山东西段、南北坡的植被不尽相同[31],从而形成了祁连山环境空间异质性,为鸡类提供了可利用的不同生态位。

几种森林鸡类蓝马鸡、血雉和斑尾榛鸡栖息地要求很相似,但它们营巢空间生态位、觅食空间生态位和营养生态位互有不同[6]。雉鹑分布于海拔3100—4100 m的森林和高山灌丛;雉鸡适应性强,利用的生境广,在祁连山分布海拔1900 m以下,与上述几种森林鸡类分布生境没有重叠。

6种草原-草甸-灌丛型鸡类隶属于3个属,组成3对近缘种,都是草食性,食物上相互竞争。但是它们栖息空间不同,相互替代。斑翅山鹑较高原山鹑分布海拔低在2800 m以下,而高原山鹑在2800 m以上。两种雪鸡分布海拔高度不同,西藏雪鸡在祁连山东、西部分别为3800—4800 m和4100—4500 m,而喜马拉雅雪鸡在西祁连山2600—3600 m[8]。由于不同海拔高度食物可利用性不同,西藏雪鸡向狭食性进化,而喜马拉雅雪鸡向广食性进化[8]。两种石鸡都喜好山地裸岩区,大石鸡分布于祁连山南坡2600—4100 m[32],而石鸡分布于北坡1890—3160 m[7],它们在接触地带杂交,形成的杂交带隔离了两个种[32]。生态位分化使得物种在竞争中共存,保持了祁连山鸡类物种多样性。

3 祁连山鸡类多样性保护

祁连山地区鸡类物种多样性分布不均匀,由东部的11种逐步减少到西部的5种,需要依据GAP分析原则检验现有自然保护区分布格局和主要保护对象能否足以保护祁连山鸡类多样性。地理概念的祁连山总面积 20.6 万km2,祁连山植被的水源涵养和冰川调控区域径流作用及丰富的野生动物资源深受各级政府和群众的重视,积极建立自然保护区。目前祁连山地区已建立10个自然保护区,其中国家级6个、省级4个,总面积52409.74 km2,占祁连山面积的25.4%。其中7个设立在祁连山东部,面积35912.95 km2,占祁连山保护区面积的68.5%,其面积对保护祁连山11种鸡类已经足够了。西祁连山有3个自然保护区,核心是甘肃盐池湾国家级自然保护区,面积13600 km2,西祁连山的5种鸡(石鸡、大石鸡、喜马拉雅雪鸡、西藏雪鸡和雉鸡)在该保护区均有分布,且两种雪鸡在核心分布区。该保护区的主要保护对象是自然生态系统、高山有蹄类和其它珍稀濒危物种[33],几种鸡类得到了良好保护。综上所述,每种鸡类和植被类型在己有保护区系统内都有,依据GAP分析原则,祁连山已建自然保护区足以保护鸡类物种多样性。

目前祁连山鸡类受胁严重的是6种以草为食的放牧型种类,两种雪鸡、两种石鸡种群受限于降水波动引发的牧草丰歉,降水充沛、牧草丰收的年份种群数量增加或保持稳定[32,34]。近20年来气温升高、降水减少和过度放牧,草原生产力大幅下降,雪鸡和石鸡数量随之减少[35,7]。虽然人类无法控制气候影响,但是随着法律的不断完善、新的牧业政策的实施和牧业生产方式的转变,超载放牧逐步解决,过度放牧给草食性鸡类带来的威胁也在缓解。

[1] 侯连海, 刘智成. 甘肃早白垩世鸟化石兼论早期鸟类的进化. 中国科学B辑, 1984, (3):250-256.

[2] 刘迺发. 甘肃鸡类物种多样性研究. 动物学研究, 1993, 9(3):233-239.

[3] Lei F M, Qu Y H, Tang Q Q, Cheng S. Priorities for the conservation of avian biodiversity in China based on the distribution patterns of endemic bird genera. Biodiversity and Conservation, 2003, 12(12):2487-2501.

[4] 王香亭, 刘迺发, 陈毅峰, 杨友桃, 胥明肃. 斑尾榛鸡的生态研究. 动物学报, 1987, 33(1):73-81.

[5] 刘迺发, 王香亭. 高山雪鸡繁殖生态研究. 动物学研究, 1990, 11(4):299-302.

[6] 刘迺发. 斑尾榛鸡成功定居青藏高原的机制 // 中国鸟类学研究. 北京:中国林业出版社, 1996.

[7] 马新年, 杨志松, 刘迺发, 金园庭. 石鸡繁殖期栖息地的特征. 动物学杂志, 2006, 41(3):1-6

[8] 刘迺发, 包新康, 廖继承. 青藏高原鸟类分类与分布. 北京:科学出版社, 2013.

[9] Lucchini V, Hoglund J, Klaus S, Swenson J, Randi E. Historical biogeography and a mitochondrial DNA phylogeny of grouse and ptarmigan. MolecularPhylogenetics and Evolution, 2001, 20(1):149-162.

[10] Ruan L Z, Zhang L X, Wen L Y, Sun Q W, Liu N F. Phylogeny and molecular evolution ofTetraogallusin China. Biochemical Genetics, 2005, 43(9/10):507-518.

[11] Wen L Y, Liu N F. Cytochrome b gene based phylogeny and genetic divergence ofTetraohpasisof China. Animal Biology, 2010, 60(2):133-144.

[12] Bao X K, Liu N F, Qu J Y, Wang X L, An B, Wen L Y, Song S. The phylogenetic position and speciation dynamics of the genusPerdix(Phasianidae, Galliformes). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 2010, 56(2):840-847.

[13] Zhan X J, Zheng Y, Wei F W, Bruford M W, Jia C X. Molecular evidence for Pleistocene refugia at the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau. Molecular Evolution, 2011, 20(4):3014-3026.

[14] 郑绍华. 甘肃天祝松山第二和第三地点化石及松山上新世哺乳动物群. 古脊椎动物学报, 1982, 20(3):216-227.

[15] 李吉均, 方小敏, 马海洲, 朱俊杰, 潘保田, 陈怀录. 晚新生代黄河上游地貌演化与青藏高原隆起. 中国科学:D辑, 1996, 26(4):316-322.

[16] 周尚哲, 李吉均. 第四纪冰川测年研究新进展. 冰川冻土, 2003, 25(6):660-666.

[17] 施雅风, 郑本兴, 李世杰, 叶佰生. 青藏高原中东部最大冰期时代高度与气候环境探讨. 冰川冻土, 1995, 17(2):97-112.

[18] 施雅风, 李吉均, 李炳元. 青藏高原晚新生代隆升与环境变化. 广州:广东科技出版社, 1998.

[19] 肖清华, 张旺生, 张伟, 朱创鑫, 王杰. 祁连山地区更新世以来冰期雪线变化研究. 干旱区研究, 2008, 25(3):426-432.

[20] 陈发虎, 张維信. 甘青地区的黄土地层学与第四纪冰川问题. 北京:科学出版社, 1993.

[21] 刘迺发, 黄祖豪. 中国石鸡生物学. 北京:中国科学技术出版社, 2007.

[22] Cao M M, JinY T, Liu N F, Ji W H. Effects of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau uplift and environmental changes on phylogeographic structure of the Daurian Partridge (Perdixdauuricae) in China. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 2012, 65(3):823-830.

[23] An B, Zhang L X, Browne S, Liu N F, Ruan L Z, Song S. Phylogeography of tibetan snowcock (Tetraogallustibetanus) in Qingzang-Tibetan Plateau. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 2009, 50(3):526-533.

[24] Qu Y H, Lei F M. Comparative phylogeography of two endemic birds of the Tibetan plateau, the white-rumped snow finch (Onychostruthustaczanowskii) and the Hume′s ground tit (Pseudopodoceshumilis). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 2009, 51(2):312-326.

[25] Qu Y H, Lei F M, Zhang R Y, Lu X. Comparative phylogeography of five avian species:Implications for Pleistocene evolutionary history in the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. Molecular Ecology, 2010, 19(2):338-351.

[26] 李吉均, 文世宣, 张青松, 王富葆, 郑本兴, 李炳元. 青藏高原隆起的时代、幅度和形式的探讨. 中国科学 A 辑, 1979, 22(6):608-616.

[27] 张荣祖. 中国自然地理--动物地理. 北京:科学出版社, 1979.

[28] Kozlova E V. 西藏高原鸟类分布及其类缘关系和历史. 动物学报, 1953, 5(1):25-36.

[29] Barbanera F, Marchi C, Guerrini M, Panayides P, Sokos C, Hadjigerou P. Genetic structure of Mediterranean chukar (Alectorischukar, Galliformes) populations:conservationand management implications. Naturwissenschaften, 2009, 96(10):1203-1212.

[30] 王香亭. 甘肃脊椎动物志. 兰州:甘肃科学技术出版社, 1991.

[31] 陈桂琛, 彭敏, 黄荣福, 卢学峰. 祁连山地区植被特征及其分布规律. 植物学报, 1994, 36(1):63-72.

[32] 刘迺发, 黄族豪, 文陇英. 大石鸡亚种分化及——新亚种描述(鸡形目, 雉科). 动物分类学报, 2004, 29(3):600-605.

[33] 刘迺发, 张惠昌, 窦志刚. 甘肃盐池湾国家级自然保护区综合科学考察. 兰州:兰州大学出版社, 2010.

[34] Liu N F. Breeding behaviour Koslov′s snowcock (Tetraogallushimalayensiskoslowi) in northwestern Gansu, China. Game and Wildlife, 1994, 11(2):167-177.

[35] 闫永峰, 王玉玲, 朱杰, 倪自银, 刘迺发. 甘肃省东大山自然保护区和盐池湾自然保护区高山雪鸡繁殖期种群密度调查. 四川动物, 2008, 27(1):70-74.

Diversity and evolutionary origins of Gallinaceans in the Qilian Mountains

WEN Longying*

KeyLaboratoryofCollegesandUniversitiesinSichuanProvinceforProtectingEndangeredBirdsintheSouthwestMountains,DepartmentofLifeSciences,LeshanNormalUniversity,Leshan614000,China

The Qilian Mountains are situated on the northeastern edge of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and are home to diverse rare and endemic gallinacean bird species. These include eleven species and five subspecies of gallinaceans belonging to two families; nine of these species are polytypic in the Qilian Mountains. This diversity arose from speciation events, in part because the Qilian Mountains have experienced several ice ages. Over time, the size of the glaciers decreased until almost no valley glacier was present, leading to allopatric speciation due to spatial and temporal separation. Furthermore, the Qilian Mountains have served as a refuge for some birds during the Pleistocene glaciations, which also led to the differentiation of subspecies due to isolation. For example, thechukarpartridge (Alectorischukar), Tibetan partridge (Perdixhodgsoniae), blood pheasant (Ithaginiscruentus), and common pheasant (Phasianuscolchicus) each have two subspecies in the Qilian Mountains. Pairs of subspecies are distributed in the eastern and western regions, or the southern and northern slopes, representing geographical speciation. Furthermore, gallinacean species diversified due to the residual distribution of native birds and the arrival of birds from elsewhere. The forest gallinaceans gradually withdrew from the plateau surface with the plateau uplift that occurred during the Quaternary glacial period. The eastern Qilian Mountains were affected by the East-Asian Monsoon, and humid air led to increased precipitation, resulting in a cold-temperature coniferous forest at an altitude of 2500—3300 m. Thus, the native forest gallinaceans remained in the Qilian Mountains. Since the middle Pleistocene, a dry and cold climate has led to the development of an alpine sub-ice-snow vegetation zone at the top of the mountain, which is a suitable habitat for grassland gallinaceans. Birds such as the Tibetan snow cock (Tetraogallustibetanus), Himalayan snow cock (Tetraogallushimalayensis),chukarpartridge, and Tibetan partridge originated from different parts of the world, enriching gallinacean diversity of this region. Diversity has also been achieved due to complex spatial heterogeneity and niche differentiation, meaning that suitable habitats and niches are available to meet different habitat requirements. For example, the habitats of the blue-eared pheasant (Crossoptilonauritum), blood pheasant, and Chinese grouse (Tetrastessewerzowi) are similar, but their spatial nesting, foraging, and nutritional niches differ. Six types of shrub-grassland-meadow gallinaceans, belonging to three genera and composed of three closely related herbivorous species, are observed. In addition to competition for food, their habitats were replaced with each other. Thus, despite competition, species can coexist due to niche differentiation, maintaining species diversity. Finally, gallinacean diversity is well protected in nature reserves. At present, 10 nature reserves, including six national and four provincial, are located in the Qilian Mountains. Each gallinacean species and subspecies has been found among these protected areas. On the basis of the geographic approach to protect biological diversity (GAP) analysis, we found the existing nature reserves in the Qilian Mountains to be sufficient for protection of gallinacean species diversity.

Qilian Mountains; gallinaceans; species diversity; residual distribution; new arrivals; spatial heterogeneity

国家自然科学基金面上项目(31372171); 四川省科技厅项目(2013JY0073)

2014-03-30;

2014-12-24

10.5846/stxb201403300596

*通讯作者Corresponding author.E-mail: lywen02@126.com

文陇英.祁连山鸡类物种多样性及其成因.生态学报,2015,35(20):6769-6773.

Wen L Y.Diversity and evolutionary origins of Gallinaceans in the Qilian Mountains.Acta Ecologica Sinica,2015,35(20):6769-6773.

——和田盘羊