千岛湖陆桥岛屿鸟类集团对栖息地片段化的敏感性及其季节变化

刘 超, 丁志锋, 丁 平,*

1 浙江大学生命科学学院, 杭州 310058 2 广东省昆虫研究所 & 华南濒危动物研究所, 广州 510260

千岛湖陆桥岛屿鸟类集团对栖息地片段化的敏感性及其季节变化

刘 超1, 丁志锋2, 丁 平1,*

1 浙江大学生命科学学院, 杭州 310058 2 广东省昆虫研究所 & 华南濒危动物研究所, 广州 510260

为探究千岛湖陆桥岛屿不同鸟类集团对栖息地片段化敏感性的差异和季节变化,于2009年4月—2012年1月鸟类繁殖季(4、5、6月)和冬季(11、12、1月)对千岛湖41个陆桥岛屿鸟类集团进行了研究。结果表明,冬季杂食鸟对片段化敏感性高于食虫鸟,繁殖季时二者无显著差异,繁殖季和冬季时下层鸟对片段化敏感性均高于林冠鸟,冬季留鸟对片段化敏感性高于候鸟,繁殖季则无显著差异。杂食鸟和留鸟对片段化敏感性存在季节差异,而食虫鸟、林冠鸟、下层鸟和候鸟对片段化敏感性均无季节差异。不同鸟类集团对栖息地片段化敏感性的差异和季节变化规律,有助于人们在栖息地管理和保护区设计时采取更有针对性的鸟类保护措施。

鸟类集团; 栖息地片段化; 敏感性; 季节差异

栖息地丧失和片段化是导致物种多样性丧失的最重要因素[1-2]。栖息地片段化后,各种片段化效应将导致物种多样性的丧失[3-5],进而影响生物群落物种组成与多样性及其动态[5-8]。因此,深入了解栖息地片段化对物种多样性和群落的影响成为当今生态学与保护生物学学领域的核心问题之一[3,5]。鸟类作为人类最为关注的生物类群之一,栖息地片段化对其多样性与群落的影响亦已引起鸟类学家的广泛关注[6,9-13]。

集团是指一群具有相似的方式探索和利用同类环境资源的物种集合和群落功能单位[14]。作为群落功能群的重要类型,通过鸟类群落集团划分有助于从功能群的角度探究鸟类物种在群落中的功能定位[15-16],分析群落内部物种相互关系,评估物种对资源和环境变化的响应[17-18]。集团已成为鸟类群落功能群研究的常用方法[19-21],从集团角度揭示片段效应亦已成为了片段化研究的热点之一[22]。

栖息地片段化不仅影响鸟类的物种多样性和和丰富度,也影响着鸟类的群落及其集团结构。不同鸟类对片段化的敏感性不同,使得不同鸟类集团对片段化的敏感性亦存在差异[23]。已有研究显示,候鸟和留鸟[16]、核心种和边缘种[8]、不同食性[24-27]和取食基底集团[28-31]等不同类型和功能群的鸟类对栖息地片段化的响应均呈现不同的规律。然而,以往的研究大部分是在陆地栖息地岛屿中进行,而鸟类群落集团在陆桥岛屿和陆地栖息地岛屿间对片段化的敏感性和响应是否存在相同的模式需进一步验证。

因大坝建设形成的人工湖泊型陆桥岛屿,其形成时间较为一致、隔离基质单一、边缘分明,排除很多其它因素的干扰,因而是较为理想的研究栖息地片段化问题平台[32-33]。为此,本研究以千岛湖陆桥岛屿为研究平台,选择食性、取食基底和居留类型等功能性状将鸟类进行集团划分,研究鸟类集团的物种丰富度和岛屿面积关系、鸟类集团对栖息地片段化的敏感性与季节变化,以及不同鸟类集团敏感性差异及其季节变化的机制。

1 研究地区和方法

1.1 研究地区

千岛湖位于浙江省淳安县境内,是1959年新安江水库建成后形成的拥有众多陆桥岛屿的人工湖泊。在最高水位108 m时,面积大于0.25 hm2的岛屿有1078个[34]。千岛湖地区为典型的亚热带季风型气候,四季分明,夏季温暖湿润,冬季寒冷少雨,年平均气温为17.0℃,年平均降水量为1430 mm。Hu等[7]对该地区植物调查共记录野生维管束植物456种,其中乔木120种,灌木61种,草本232种,藤本43种。岛屿间植被类型比较一致,乔木以马尾松(Pinusmassoniana)为主,还有苦槠(Castanopsissclerophylla)、柏树(Platycladusorientalis)等;灌木层主要为满山红(Rhododendronmariesii)、盐肤木(Rhuschinensis)、黄檀(Dalbergiaodrifera)、檵木(Loropetalumchinese)等;草本主要为芒萁(Dicranopterisdichotoma),夹杂一些矮竹丛。

1.2 研究方法

1.2.1 岛屿参数获取

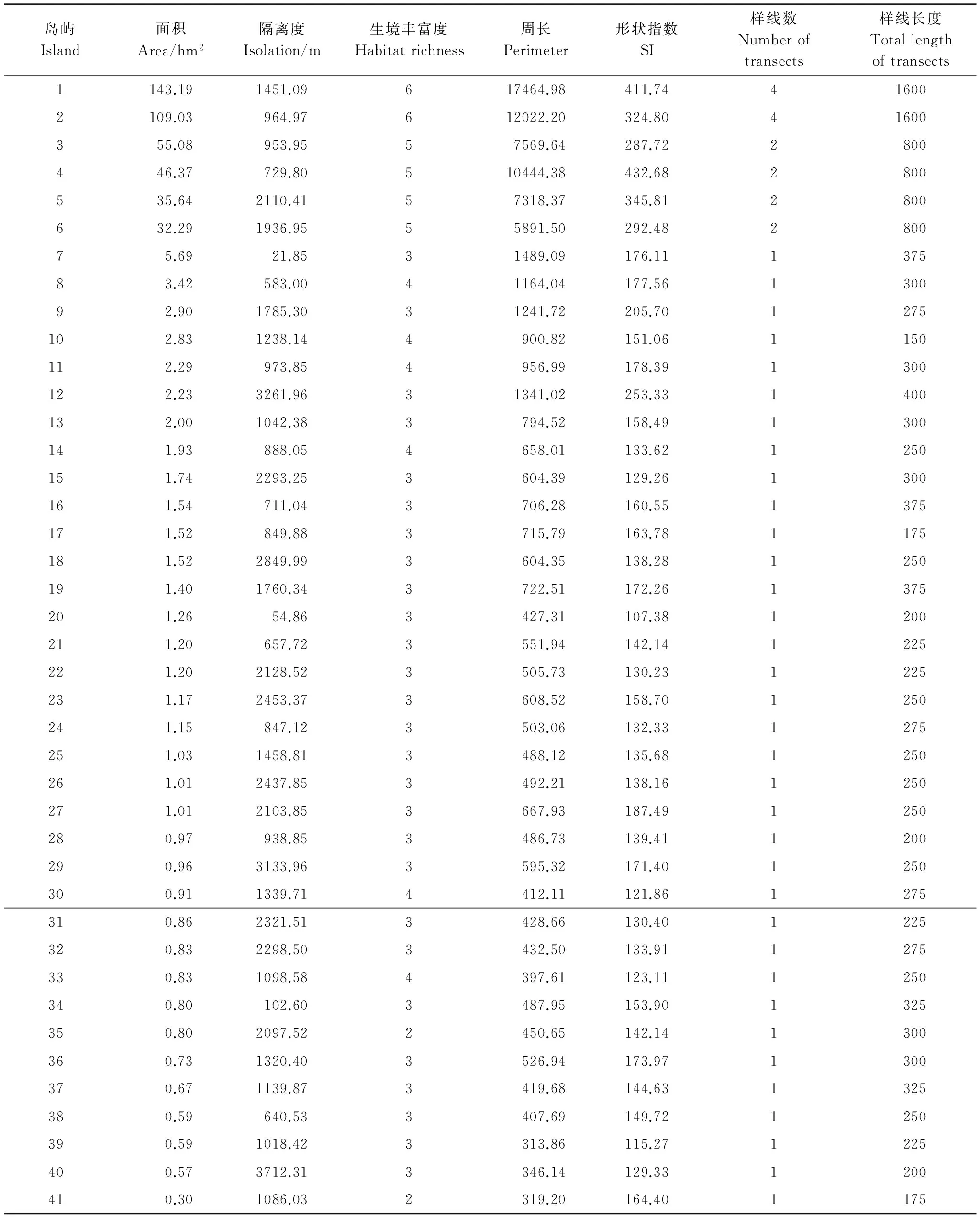

根据岛屿面积、隔离度(距大陆的最近距离)梯度选取41个调查样岛,测定岛屿面积、隔离度等,并计算岛屿形状指数(SI)[34]。SI=P/[2×(π×A)0.5],式中P为岛屿周长,A为岛屿面积。将岛屿植物生境划分为7个类型:针叶林、阔叶林、针阔混交林、竹林、灌丛、杂草和农田[35],以岛屿上所包含植物生境类型的数量作为生境丰富度[36]。具体参数见附表1。

1.2.2 鸟类群落调查方法

鸟类调查采用样线法进行分层随机取样调查[37]。根据岛屿面积按照一定比例确定岛屿样线长度、数量(41个岛屿样线长度及数量见附表1),每个季节(繁殖季和冬季)对每个岛屿各调查9遍,调查强度能确保有效记录各岛屿上的鸟类。于2009年4月—2012年1月鸟类繁殖季(4、5、6月)和冬季(11、12、1月)沿着各岛屿样线行走,沿途记录样线两侧25m范围内看到或听到鸟类的名称、数量及行为等数据。调查选择在晴朗、无风的天气条件下进行,根据鸟类活动规律确定调查时间。调查选择在日出和日落前后鸟类活动高峰期进行,日出前半个小时开始,到11:00结束;15:00开始,日落前半个小时结束,具体调查时间参考光线强弱和实际鸟况进行调整。每个研究岛屿由不同调查者完成且每次调查顺序随机选择,以尽量减少人为因素和实验设计产生的误差,确保鸟类调查的科学性和准确性。

1.2.3 鸟类集团的划分

通过野外观察并参考O′Connell 等[38]和Canterbury等[39]的研究方法,结合《浙江动物志·鸟类》[40]对鸟类的详细介绍,将所有调查记录的鸟类按照以下三类指标进行集团划分:食物类型、取食基底和居留类型。具体划分见表1。由于物种丰富度高于3的鸟类集团才具有一定统计功效,本研究仅分析岛屿上物种丰富度大于3的鸟类集团:留鸟、候鸟,食虫鸟、杂食鸟,林下层取食鸟、林冠层取食鸟。研究所记录的全部鸟类所属集团详细情况见附表2。

1.2.4 鸟类集团对栖息地片段化敏感性的比较

经典的岛屿生物地理学理论认为,物种丰富度面积关系能较好阐明片段化栖息地中物种丰富度与斑块面积之间的变化关系,物种丰富度随着岛屿面积的增加而增加,随着隔离度的增加而减少,而物种丰富度面积关系曲线的斜率z值大小可以衡量物种对栖息地片段化的敏感性,z值越大,物种对片段化越敏感,反之则对片段化越不敏感[41-43]。采用Zar[44]的方法对不同回归方程z值差异性进行检验。该方法统计表达式为td=(b1-b2) /Sb1-b2,式中b1和b2为回归斜率,Sb1-b2为回归斜率间的标准误。然后通过t分布t(td,df)得到概率分布值p, df表示自由度。所有显著性差异设定若P<0.05,则两个z值之间存在显著差异,表明不同鸟类集团敏感性存在显著差异,反之,则敏感性无显著差别。

2 数据处理

根据丁志锋[45]对各岛屿参数(面积、隔离度、PAR、形状指数、栖息地多样性、植物物种丰富度)所作的Pearson相关性检验和共线性分析结果,岛屿形状指数和生境多样性与岛屿面积呈现很强正相关(r> 0.8),将其剔除以避免对统计结果的干扰[46]。且所有参数VIF值小于10,表明共线性不影响最终结果。本研究选择解释度较高的幂函数模型(logS=logc+z×logA,式中S为岛屿物种丰富度,A为岛屿面积,c和z均为常数)研究鸟类集团物种丰富度与岛屿面积之间的关系。统计分析采用R software 2.13和SPSS19.0进行,绘图在Excel 2007中完成。

3 结果

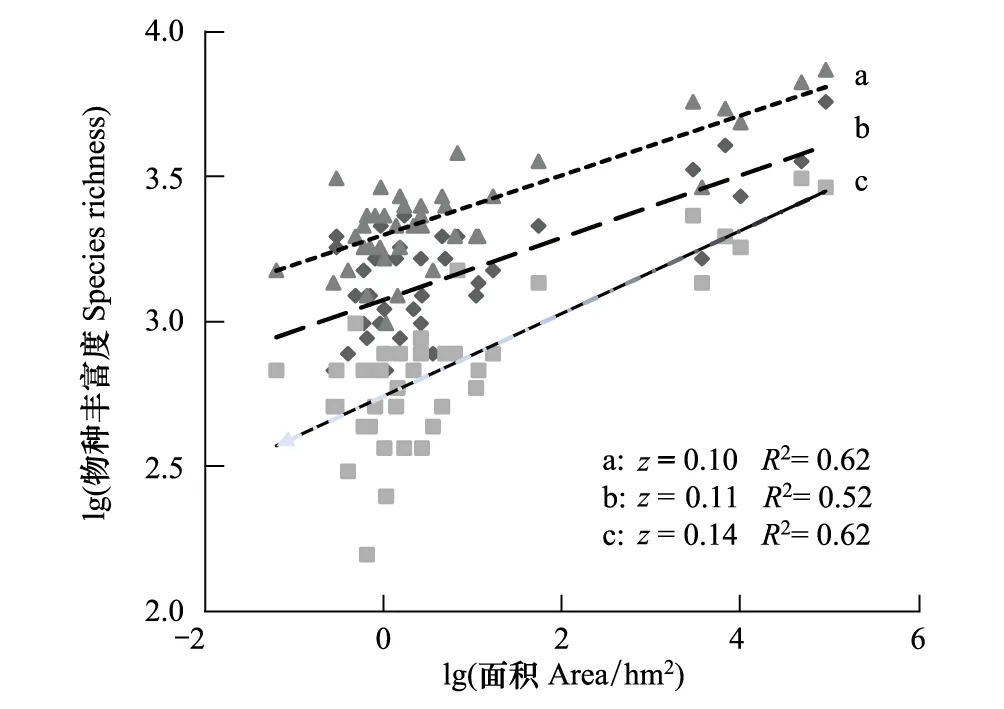

3.1 不同季节同一鸟类集团的敏感性

繁殖季共记录61种鸟,冬季共记录52种鸟。繁殖季和冬季调查记录的不同鸟类集团物种丰富度见表1。繁殖季和冬季各鸟类集团物种丰富度岛屿面积关系z值在0.07—0.21之间(图1,图2)。杂食鸟和留鸟对片段化敏感性存在季节差异(P<0.05),食虫鸟、林冠鸟、下层鸟和候鸟对片段化敏感性则无季节差异(P>0.05)。

图1 所有鸟类(a)、繁殖季(b)和冬季(c)鸟类物种丰富度面积关系Fig.1 Species-area relationship of all birds(a), birds in breeding(b) and winter(c) seasons

3.2 同一季节不同鸟类集团的敏感性

在繁殖季,岛屿所有鸟类物种丰富度与岛屿面积关系z值为0.11,冬季所有鸟类物种丰富度与岛屿面积关系z值为0.14,两个季节全部鸟类物种丰富度面积关系z值为0.10,三者之间无显著差异(P> 0.05)。所有鸟类集团中,冬季杂食鸟对片段化敏感性高于食虫鸟(P< 0.05),繁殖季时二者无显著差异(P> 0.05),繁殖季和冬季下层鸟对片段化敏感性均高于林冠鸟(P<0.05),冬季留鸟对片段化敏感性高于候鸟(P<0.05),繁殖季则无显著差异(P> 0.05)。

4.1 不同季节同一鸟类集团的敏感性差异

研究结果显示,千岛湖陆桥岛屿上繁殖季和冬季各自包含的所有物种对栖息地片段化的敏感性无差异;但不同食性、取食基底和居留型鸟类集团对栖息地片段化的敏感性存在差异,部分集团的敏感性存在季节变化。鸟类群落和各鸟类集团对片段化敏感性表现出不同规律,这也表明通过更加细致的集团划分深入探究鸟类群落动态变化规律是有必要的。各鸟类集团的物种丰富度面积关系z值相较于陆地片段化栖息地中研究结果偏低,这可能和本地区岛屿隔离度较小从而导致鸟类较高迁移频繁及较低灭绝速率有关[47-48]。调查发现,红头长尾山雀(Aegithalosconcinnus)和大山雀(Parusmajor)等体型小、飞行能力相对有限的鸟类几乎在所有岛屿都有分布,且在岛屿间频繁迁移,可见隔离度对其影响有限。

表1 鸟类集团划分及繁殖季、冬季各集团物种丰富度(“/”前半部分:繁殖季物种丰富度,”/”后半部分:冬季物种丰富度)

图2 繁殖季(a)和冬季(b)不同食性、取食基底、居留型的鸟类集团物种丰富度面积关系Fig.2 Relationships between species richness of bird guild with different dietary type、foraging strata、migratory status and island area in the breeding(a) and winter(b) seasons

4 讨论

食物是影响鸟类对片段化敏感性的重要因素,食物资源获得情况影响鸟类取食效率和繁殖成功率。此外,鸟类食性、觅食位置、特定环境依赖性、扩散能力和栖息地特征也会对敏感性产生影响[31]。Zannette等[49]的研究表明,面积小的森林斑块中鸟类食物资源相对短缺。千岛湖陆桥岛屿面积较小,植被类型较为单一,且该地区气候存在明显的季节变化,食物的种类和数量会产生季节波动,引发各鸟类集团对片段化敏感性的不同程度响应。

以往在陆地片段化斑块中的研究表明,食虫鸟、下层鸟等集团往往对片段化敏感性更高,敏感性强弱也更容易受到影响[29,50]。对千岛湖陆桥岛屿鸟类集团敏感性研究发现,杂食鸟和留鸟对栖息地片段化的敏感性存在季节差异,其敏感性时间波动大,而其它鸟类集团未表现出季节差异。本地区杂食鸟和留鸟中,以白头鹎(Pycnonotussinensis)、黑鹎(Hypsipetesleucocephalus)等鹎类常见,这些鸟对本地环境适应性强、分布广,在资源呈现季节变化时,这些鸟在大陆和岛屿间分布呈现季节性规律,表现出敏感性的季节差异。这一规律与陆地片段化栖息地中鸟类集团呈现的规律不同,造成这种差异的原因可能是多方面的,可能与千岛湖陆桥岛屿面积较小、植被类型较为单一以及本地区气候存在显著的季节分化有关。小型斑块中的食物资源季节性波动,冬季时食物资源相对匮乏,部分集团敏感性会随之上升。

陆地斑块普遍具有面积及隔离度大、边界模糊、隔离基质复杂多样、斑块内部植被类型多样等特征,而陆桥岛屿面积和隔离度较小、边界清晰、隔离基质单一、植被类型简单。两类生态系统具有完全不同的特点,因而在片段化研究中常常呈现不同的规律。以往的研究表明,千岛湖陆桥岛屿植物、蜥蜴、小型兽类、鸟类等不同类群的分布具有不同于陆地斑块的格局和决定机制[36,51],此次对鸟类集团敏感性季节变化规律的研究进一步揭示:陆桥岛屿鸟类集团对片段化敏感性及变化具有不同于陆地斑块的规律。这种差异在保护区建设和栖息地管理时需要考虑。

4.2 同一季节不同鸟类集团的敏感性差异

以往对陆地斑块栖息中鸟类食性集团研究表明,食虫鸟比杂食鸟对片段化的敏感性更高。这与食虫鸟对食物需求更加固定有关,也和它们对栖息地要求更高有关[25,52]。本研究结果恰恰相反,繁殖季时二者对片段化的敏感性无显著差异,冬季杂食鸟对片段化的敏感性甚至高于食虫鸟。在小型陆桥岛屿片段化栖息地中,资源有限会导致鸟类种间竞争加剧,杂食鸟的食性占据生态位更宽,物种彼此间更易产生生态位重叠或挤压,导致竞争加剧、鸟类集团敏感性增加。食虫鸟相比于杂食鸟,可选择食物种类少,但陆桥岛屿特定的环境使得其在岛屿间能频繁迁移获得食物,在一定程度上也削弱了食虫鸟的敏感性。

研究发现,无论在繁殖季或冬季,下层鸟比林冠鸟对栖息地片段化都更加敏感,这和陆地斑块中关于鸟类集团的研究结果相同。这可能与下层鸟在岛屿间扩散能力较差有关,而林冠鸟的活动特点使得其具备较强穿越林层能力,扩散能力更强。因而相比于下层鸟,林冠鸟对片段化不敏感[29-31]。

关于留鸟和候鸟对栖息地片段化的响应,多数研究表明,片段化对留鸟的影响要大于候鸟,留鸟对片段化的敏感性高于候鸟。这与留鸟常年生活在某个区域从而对栖息地有特定要求有关,也和其对本地营巢及食物资源要求较高有关[16,53]。留鸟和候鸟可能受到彼此正的相互作用影响,这种机制被称为“异种特异性吸引”。候鸟选择栖息地可能会参考留鸟的选择,使得二者对栖息地片段化的敏感性更加相近,这在繁殖季有时更加明显[54]。千岛湖陆桥岛屿留鸟和候鸟集团在繁殖季时对片段化敏感性无显著差异,而在冬季时留鸟对片段化敏感性更高,不同季节可能存在不同机制影响留鸟和候鸟对片段化敏感性的相对强弱。

致谢:斯幸峰、宋虓、丁文勇对实验数据处理提供帮助,王思宇、吴强、陈传武等参与野外工作,淳安县林业局和千岛湖国家森林公园管理部门对研究给予支持,特此致谢。

[1] Raffaelli D. How extinction patterns affect ecosystems. Science, 2004, 306(5699):1141-1142.

[2] Pimm S L. Biodiversity:Climate change or habitat loss-Which will kill more species?. Current Biology, 2008, 18(3):R117-R119.

[3] Saunders D A, Hobbs R J, Margules C R. Biological consequences of ecosystem fragmentation:A review. Conservation Biology, 1991, 5(1):18-32.

[4] Ewers R W, Didham R K. Confounding factors in the detection of species responses to habitat fragmentation. Biological Reviews, 2006, 81(1):117-142.

[5] Laurance W F. Theory meets reality:how habitat fragmentation research has transcended island biogeographic theory. Biological Conservation, 2008, 141(7):1731-1744.

[6] Boulinier T, Nichols J D, Hines J E, Sauer J R, Flather C H, Pollock K H. Forest fragmentation and bird community dynamics:inference at regional scales. Ecology, 2001, 82(4):1159-1169.

[7] Hu G, Feeley K J, Wu J G, Xu G F, Yu M J. Determinants of plant species richness and patterns of nestedness in fragmented landscapes:evidence from land-bridge islands. Landscape Ecology, 2011, 26(10):1405-1417.

[8] Yu M J, Hu G, Feeley K J, Wu J G, Ding P. Richness and composition of plants and birds on land-bridge islands:effects of island attributes and differential responses of species groups. Journal of Biogeography, 2012, 39(6):1124-1133.

[9] Andrén H. Effects of habitat fragmentation on birds and mammals in landscapes with different proportions of suitable habitat:a review. Oikos, 1994, 71(3):355-366.

[10] Wiens J A. Habitat fragmentation:island v landscape perspectives on bird conservation. Ibis, 1994, 137(S1):S97-S104.

[11] Borgella R Jr, Gavin T A. Avian community dynamics in a fragmented tropical landscape. Ecological Applications, 2005, 15(3):1062-1073.

[12] Watson J E M, Whittaker R J, Freudenberger D. Bird community responses to habitat fragmentation:how consistent are they across landscapes?. Journal of Biogeography, 2005, 32(8):1353-1370.

[13] Zuckerberg B, Porter W F. Thresholds in the long-term responses of breeding birds to forest cover and fragmentation. Biological Conservation, 2010, 143(4):952-962.

[14] Root R B. The niche exploitation pattern of the blue-gray gnatcatcher. Ecological Monographs, 1967, 37(4):317-350.

[15] Freemark K E, Merriam H G. Importance of area and habitat heterogeneity to bird assemblages in temperate forest fragments. Biological Conservation, 1986, 36(2):115-141.

[16] Lampila P, Mönkkönen M, Desrochers A. Demographic responses by birds to forest fragmentation. Conservation Biology, 2005, 19(5):1537-1546.

[17] Holmes R T, Bonney R E Jr, Pacala S W. Guild structure of the Hubbard Brook bird community:a multivariate approach. Ecology, 1979, 60(3):512-520.

[18] Block W M, Finch D M, Brennam L A. Single-species versus multiple-species approaches for management // Martin T E, Finch D M, eds. Ecology and Management of Neotropical Migratory Birds:A Synthesis and Review of Critical Issues. Oxford:Oxford University Press, 1995:461-476.

[19] Park C R, Lee W S. Relationship between species composition and area in breeding birds of urban woods in Seoul, Korea. Landscape and Urban Planning, 2000, 51(1):29-36.

[20] Lim H C, Sodhi N S. Responses of avian guilds to urbanisation in a tropical city. Landscape and Urban Planning, 2004, 66(4):199-215.

[21] Sandström U G, Angelstam P, Mikusiński G. Ecological diversity of birds in relation to the structure of urban green space. Landscape and Urban Planning, 2006, 77(1/2):39-53.

[22] Kattan G H, Alvarez-López H, Giraldo M. Forest fragmentation and bird extinctions:San antonio eighty years later. Conservation Biology, 1994, 8(1):138-146.

[23] Vetter D, Hansbauer M M, Végvári Z, Storch I. Predictors of forest fragmentation sensitivity in Neotropical vertebrates:a quantitative review. Ecography, 2011, 34(1), doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.2010.06453.x.

[25] Gray M A, Baldauf S L, Mayhew P J, Hill J K. The response of avian feeding guilds to tropical forest disturbance. Conservation Biology, 2007, 21(1):133-141.

[27] Giraudo A R, Matteucci S D, Alonso J, Herrera J, Abramson R R. Comparing bird assemblages in large and small fragments of the Atlantic Forest hotspots. Biodiversity and Conservation, 2008, 17(5):1251-1265.

[28] Dale V H, Pearson S M, Offerman H L, O′Neill R V. Relating patterns of land-use change to faunal biodiversity in the central Amazon. Conservation Biology, 1994, 8(4):1027-1036.

[29] Stouffer P C, Bierregaard R O Jr. Use of Amazonian forest fragments by understory insectivorous birds. Ecology, 1995, 76(8):2429-2445.

[30] Stratford J A, Stouffer P C. Local extinctions of terrestrial insectivorous birds in a fragmented landscape near Manaus, Brazil. Conservation Biology, 1999, 13(6):1416-1423.

[31] Ribon R, Simon J E, De Mattos G T. Bird extinctions in Atlantic forest fragments of the Viçosa region, southeastern Brazil. Conservation Biology, 2003, 17(6):1827-1839.

[32] Diamond J M. Dammed experiments!. Science, 2001, 294(5548):1847-1848.

[33] Wu J G, Huang J H, Han X G, Xie Z Q, Gao X M. Three-Gorges Dam-Experiment in habitat fragmentation?. Science, 2003, 300(5623):1239-1240.

[34] Ding Z F, Feeley K J, Wang Y P, Pakeman R J, Ding P. Patterns of bird functional diversity on land-bridge island fragments. Journal of Animal Ecology, 82(4):781-790.

[35] 张竞成, 王彦平,蒋萍萍,李鹏,于明坚,丁平. 千岛湖雀形目鸟类群落嵌套结构分析. 生物多样性, 2008, 16(4):321-331.

[36] Wang Y P, Bao Y X, Yu M J, Xu G F, Ding P. Biodiversity research:Nestedness for different reasons:the distributions of birds, lizards and small mammals on islands of an inundated Lake. Diversity and Distributions, 2010, 16(5):862-873.

[37] Bibby C J, Burgess N D, Hill D A, Mustoe S. Bird Census Techniques, 2nd ed. London:Academic Press, 2000.

[38] O′Connell T J, Jackson L E, Brooks R P. Bird guilds as indicators of ecological condition in the central Appalachians. Ecological Applications, 2000, 10(6):1706-1721.

[39] Canterbury G E, Martin T E, Petit D R, Petit L J, Bradford D F. Bird communities and habitat as ecological indicators of forest condition in regional monitoring. Conservation Biology, 2000, 14(2):544-558.

[40] 诸葛阳, 顾辉清, 蔡春抹. 浙江动物志:鸟类. 杭州:浙江科学技术出版社, 1990.

[41] Arrhenius O. Species and area. Journal of Ecology, 1921, 9(1):95-99.

[42] MacArthur R H, Wilson E O. The Theory of Island Biogeography. Princeton, New Jersey:Princeton University Press, 1967.

[43] Rosenzweig M L. Species Diversity in Space and Time. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press, 1995.

[44] Zar J H. Biostatistical Analysis. 3rd ed. Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education India, 1996.

[45] 丁志锋. 片段化斑块中鸟类群落结构与功能多样性格局[D]. 杭州:浙江大学, 2012.

[46] Torras O, Gil-Tena A, Saura S. How does forest landscape structure explain tree species richness in a Mediterranean context?. Biodiversity and Conservation, 2008, 17(5):1227-1240.

[47] Johnson M P, Simberloff D S. Environmental determinants of island species numbers in the British Isles. Journal of Biogeography, 1974, 1(3):149-154.

[48] Fraser G S, Stutchbury B J M. Area-sensitive forest birds move extensively among forest patches. Biological Conservation, 2004, 118(3):377-387.

[49] Zanette L, Doyle P, Trémont S M. Food shortage in small fragments:Evidence from an area-sensitive passerine. Ecology, 2000, 81(6):1654-1666.

[50] Anjos L D, Boçon R. Bird communities in natural forest patches in southern Brazil. The Wilson Bulletin, 1999, 111(3):397-414.

[51] 孙雀, 卢剑波, 邬建国, 张凤凤. 千岛湖库区岛屿面积对植物分布的影响及植物物种多样性保护研究. 生物多样性, 2008, 16(1):1-7.

[52] Stouffer P C, Bierregaard R O, Strong C, Lovejoy T E. Long-term landscape change and bird abundance in Amazonian rainforest fragments. Conservation Biology, 2006, 20(4):1212-1223.

[53] Brotons L, Mönkkönen M, Martin J L. Are fragments islands? Landscape context and density-Area relationships in boreal forest birds. The American Naturalist, 2003, 162(3):343-357.

[54] Mönkkönen M, Welsh D A. A biogeographical hypothesis on the effects of human caused habitat changes on the forest bird communities of Europe and North America. Annales Zoologici Fennici, 1994, 31:61-70.

Seasonal changes in sensitivity of bird guilds to habitat fragmentation on land-bridge islands in the Thousand Island Lake, China

LIU Chao1, DING Zhifeng2, DING Ping1,*

1CollegeofLifeSciences,ZhejiangUniversity,Hangzhou310058,China2GuangdongEntomologicalInstitute&SouthChinaInstituteofEndangeredAnimals,Guangzhou510260,China

Habitat loss and fragmentation seriously threaten global species diversity. Understanding the impact on species and communities is a core issue for ecology and conservation biology. A guild acts as a functional unit within a community. Bird guild research can help to analyze relationships among different species and evaluate their responses to habitat fragmentation. Much research has focused on bird guilds in terrestrial fragments, while other fragmented systems, such as land-bridge islands, draw relatively less attention. Because different systems tend to display different geological and ecological patterns, we needed to verify whether terrestrial fragments and land-bridge islands share common patterns of response to habitat fragmentation. The land-bridge islands in the Thousand Island Lake, which were created by dam construction, are an ideal platform for the study of habitat fragmentation. To test bird sensitivity to habitat fragmentation across seasons, we conducted bird guild studies on 41 land-bridge islands in the Thousand Island Lake during the breeding season (April-June) and winter season (November-January) of each year between April 2009, and January 2012. We classified birds into guilds according to dietary type, foraging strata, and migratory status. We used an equation with logarithmic transformation from island biogeography,S=CAz, to clarify the relationship between bird guild species richness and island fragment area. In this equation,Srepresents species richness of each bird guild,Arepresents island area,Cis a constant, andzis the slope of the species-area curve. This variable can be considered a measurement of sensitivity to habitat fragmentation. The bigger the value ofz, the greater the sensitivity of the bird guild. We extracted and compared the slope of each species-area relationship curve (zvalue) to determine whether there exists significant variation in sensitivity to habitat fragmentation among the different bird guilds. Our research indicated that omnivorous birds were more sensitive to habitat fragmentation than insectivores during the winter season, while no significant difference was found for the breeding season. Understory birds were more sensitive to habitat fragmentation than canopy birds, both in breeding and winter seasons. Resident birds were more sensitive than migrants in winter, while no significant difference between them were observed in the breeding season. Both omnivorous and resident birds showed seasonal changes in their sensitivity to fragmentation. Other guilds, including insectivorous birds, canopy birds, understory birds, and migratory birds, showed no significant seasonal changes. Previous studies conducted in terrestrial fragments support our findings that responses of bird guilds to habitat fragmentation differ and that seasonal changes in the responses to habitat fragmentation do exist. These results may aid in the effective management of bird habitats and in the design of nature reserves. Future studies may focus on other bird guild types and determine if differences in responses to habitat fragmentation occur at a larger temporal scale.

bird guild; habitat fragmentation; sensitivity; seasonal changes

附表1 41个研究岛屿参数

国家自然科学基金项目(31170397, 31210103908)

2014-06-26; < class="emphasis_bold">网络出版日期:

日期:2014-12-18

10.5846/stxb201406261319

*通讯作者Corresponding author.E-mail: dingping@zju.edu.cn

刘超, 丁志锋, 丁平.千岛湖陆桥岛屿鸟类集团对栖息地片段化的敏感性及其季节变化.生态学报,2015,35(20):6759-6768.

Liu C, Ding Z F, Ding P.Seasonal changes in sensitivity of bird guilds to habitat fragmentation on land-bridge islands in the Thousand Island Lake, China.Acta Ecologica Sinica,2015,35(20):6759-6768.

——千岛湖站