合成免疫策略治疗慢性乙肝病毒感染综述

谌 平 何成宜 陈志英

(中国科学院深圳先进技术研究院基因与细胞工程研究室 深圳 518055)

合成免疫策略治疗慢性乙肝病毒感染综述

谌 平 何成宜 陈志英

(中国科学院深圳先进技术研究院基因与细胞工程研究室 深圳 518055)

慢性乙型肝炎病毒(Hepatitis B Virus,HBV)感染可诱发肝硬化与肝癌,是危害人类健康的重大疾病。基于对 HBV 感染持续不愈主要是机体免疫功能缺陷所致的认识,提出用“合成免疫”策略重建抗 HBV 免疫功能,消除感染以预防致命病变的发生。用优化的基因治疗载体微环 DNA,在体内表达一套工程抗体,模拟急性 HBV感染康复时机体的免疫反应,由单克隆抗体中和病毒,双靶向抗体将非特异的 T 淋巴细胞转化为抗 HBV 的 T 淋巴细胞,杀死 HBV 感染的肝细胞,两者协同达到根治慢性 HBV 感染的目的。微环 DNA 安全、经济,可建立一个安全、高效、可负担的抗 HBV 免疫体系,有效消除 HBV 的危害。

乙肝病毒;慢性 HBV 感染;合成免疫;微环 DNA;过继免疫

1 引 言

乙型肝炎病毒(Hepatitis B Virus,HBV)感染严重威胁人类健康。中国有 1 亿左右、全球有超过 3 亿慢性 HBV 感染患者(Chronic Hepatitis B virus carrier,CHB),每年导致超过 60 万人死于原发性肝癌和肝硬化[1]。多数肝癌和肝硬化的发生,是由于 HBV 感染诱发肝脏持久炎症与肝细胞反复死亡增生所致,清除病毒可有效防止肝癌和肝硬化的发生。目前还缺乏经济、方便的治疗方法来有效消除 HBV 的危害。虽然现有的核苷类似物和干扰素治疗能有效抑制 HBV 的复制,减轻或消除症状,但这些治疗疗效短暂,只有长期接受治疗,才能有效预防肝硬化及肝癌的发生。由于接受长期治疗的 HBV 携带者并不多,故这种治疗对解除全球 HBV 威胁意义不大。世界卫生组织最新官方统计表明,CHB 患者接受长期抗 HBV 核苷类似物治疗的比例不超过 10%[2]。除了因为没有明显的症状,携带者不知道感染的存在而没有接受治疗外,开始治疗而中途放弃的比例很高。经济负担不是一个主要因素,每天服药造成的麻烦是主要的原因[2]。抗 HBV 感染的治疗性疫苗曾经被寄以厚望,但多个临床实验效果不彰[3,4]。虽然疫苗能有效预防 HBV 感染,并已经逐渐减少中国 HBV 携带率,但是,由于原来慢性 HBV 携带者的基数非常庞大,接近一亿之巨,加上疫苗覆盖不全,在可以预见的未来,慢性 HBV 感染及引起的肝硬化和肝癌,仍然是中国和世界最重要的健康问题。本文将系统陈述慢性 HBV 感染形成的机制以及目前的治疗现状,并提出合成免疫策略,作为根本解决 HBV 感染这个重大健康问题的方案。

2 免疫系统的缺陷是 HBV 感染持续的关键

HBV 是一种典型的非致细胞病变病毒,病毒本身对肝细胞不会造成病理伤害。肝脏病变的发生,是由于机体的免疫系统清除病毒的过程,造成肝脏的炎症反应,包括肝细胞死亡,转氨酶升高。有资料表明,在中国感染过 HBV的总人数超过 6 亿人,但大部分人的机体能产生有效的免疫反应,将病毒完全清除,并获得终生免疫。其中,康复过程包括机体产生中和抗体灭活病毒,细胞毒性 T 淋巴细胞(Cytotoxic Lymphocyte,CTL)杀灭带毒的肝细胞,两者协同达到根治的效果,且这种抗 HBV 免疫终生有效。但是,在从急性感染康复多年之后,用敏感的检测方法仍可在肝脏中检测到微量的cccDNA,血液中也可检测到 HBV 病毒颗粒。这表明,康复不一定伴随 HBV 全部消灭,而是建立起一个有效的免疫监督机制,使残留的cccDNA 不能大量复制造成复发。临床上发现HBV 感染康复多年后,在机体的免疫系统受抑制如接受免疫抑制治疗时,HBV 感染复发,与这个假说相吻合。

多方面的证据表明,HBV 感染迁延不愈转化为慢性的主要机制是宿主的免疫功能受损,对 HBV 各种抗原产生不同程度的免疫耐受,不能像大多数成人那样有效地清除 HBV[5]。慢性HBV 感染最多是母婴传播的结果,其次是儿童期感染,成年人感染转为慢性者较少。 母婴传播包括妊娠期、分娩期间和哺乳期的感染。胎儿期通过胎盘途径接触病毒抗原,免疫系统可通过“阴性选择”,将 HBV 特异性 T 细胞克隆清除,结果不论是胎儿期、分娩期或更迟才感染 HBV 病毒,感染都将持续[5,6]。新生儿通过母婴传播感染 HBV 病毒后,90% 以上会发展成为慢性感染,是为“新生儿免疫耐受”。3 岁以前的幼儿期,机体免疫系统发育还不健全,也容易造成慢性感染[5,7]。而当成人感染 HBV 时,超过90% 的人都能清除病毒得以痊愈,只有不到 5%的人群发展成为慢性感染。成人感染 HBV 的免疫耐受主要机制为个体免疫系统不健全,如 Th1/ Th2 细胞失衡、病毒特异性 CD8+T 细胞功能损伤、树突状细胞(Dendritic Cell,DC)功能缺陷、调节性 T 细胞(Regulatory T Cell,Treg)增多、免疫抑制途径异常活跃等[5,8-10]。在对 CHB 病程进一步分析的基础上,可把 CHB 分为免疫耐受期和免疫清除期[11]。在免疫耐受期病毒滴度可高达109~1010/mL,而肝脏不见任何炎症反应,血液也检测不到标志肝细胞损伤的转氨酶异常,表明机体免疫系统对病毒几乎不产生任何反应;免疫耐受期持续的时间长短不一,可长达 30 年以上;随后,可进入免疫清除期,表现为一次或多次的急性肝炎症状,HBV 病毒滴度下降,经数次反弹之后,病毒滴度维持在较低水平,但肝脏严重损害导致纤维化与肝硬化;HBV 持续感染往往导致病毒突变株出现,可能是机体免疫选择压力的结果[11]。CHB 彻底持久清除 HBV,像急性HBV 感染后康复者很少见。

在急性 HBV 感染时,机体产生强烈免疫应答,HBV 特异的细胞毒性 T 细胞(CTL)是清除病毒的主要效应细胞;抗体在预防 HBV 感染起关键作用,但在清除 HBV 感染过程中的作用较小。 用黑猩猩所做的 HBV 感染实验表明,用抗体耗尽血液中的 CD4+T 细胞,CD8+CTL 仍能有效清除病毒[12],这突显 CD8+CTL 细胞在该过程的重要作用。CTL 细胞主要通过肝细胞溶解途径,清除病毒;此外,还可通过促进病毒基因组降解的非细胞溶解机制清除病毒[13]。相比之下,慢性 HBV 感染时,CTL 免疫应答要弱得多,无法有效清除病毒感染。有研究表明,在慢性感染患者,特别是病毒 DNA 载量高者,其外周血中难以检测到 HBV 特异的 CTL[14]。

3 重建抗 HBV 免疫可治疗慢性 HBV 感染

3.1 骨髓移植

多方面的证据表明, 通过移植抗 HBV 获得性免疫的方法,可以清除 HBV,并建立持久的抗 HBV 免疫机制。有多个报道表明,合并慢性 HBV 感染患者通过骨髓移植,在重建造血和免疫系统的同时,体内的 HBV 也被清除[15],提示捐赠者的骨髓为受捐者提供了抗 HBV 免疫机制。Lau 等[15]报道的 21 例接收骨髓移植的合并HBV 感染的淋巴瘤患者中,5 例接受了抗-HBs/抗-HBc 阳性的骨髓移植,有 2 例(40%)产生持续的 HBsAg 血清学阴转;而其余 16 例接受抗-HBs 阴性供体骨髓移植的患者,无人发生阴转。详细分析接受移植者体内 T 淋巴细胞后发现:抗 HBV 特异性 T 细胞来源于骨髓供体;而抗-HBs 阴性供体体内缺乏抗 HBV 特异性 T 细胞,故此,没有一例发生 HBV 感染状态的变化。这些令人信服的证据证明,供者抗 HBV 的免疫功能被转移到受者体内并产生治疗效果[16,17]。还有研究表明,接受骨髓移植后的 HBsAg 阴转率明显高于自发的转换率或应用干扰素后的阴转率[18],进一步支持该假说。这些成功的个案,成为支持我们提出的合成免疫治疗 CHB 的基础。

尽管如此,骨髓移植治疗慢性 HBV 感染技术没有普遍用于临床,除了费用高昂的因素外,骨髓移植潜在的危险是重要的限制。骨髓移植存在固有的免疫排斥反应问题,常常需要终生服用免疫抑制药以控制排斥反应;此外,慢性 HBV携带者在接受骨髓移植后,可能激活 HBV 大量复制,诱发肝炎甚至致命的重型肝炎[19,20]。

3.2 细胞治疗

细胞治疗指的是将外周血或脐带血的单核细胞在体外用细胞因子诱导扩增后回输到体内的治疗方法。细胞疗法有多种,如 CIK 细胞,DCCIK 细胞、DC 细胞等。有报道表明,细胞治疗对 HBV 感染有一定疗效。

CIK 即细胞因子诱导的杀伤细胞,是一类具有 T 细胞与自然杀伤细胞特性的免疫效应细胞。其他免疫效应细胞如 CTL,只能识别 MHC 递呈的抗原,称为 MHC 依赖性免疫细胞。与此不同,CIK 细胞能在不依赖 MHC 的情况下识别、杀死感染细胞或癌细胞,反应迅速、精确,加上细胞毒力强、易于增殖等优点,已经被广泛应用于肿瘤免疫治疗,也有用于治疗 CHB 的尝试。CIK 的作用机制还没有完全了解,但已知该细胞通过 NKG2D、DNAM-1 与 NKp30 等受体介导细胞与细胞之间直接接触而发挥作用,肿瘤常常过表达 NKG2D 而成为 CIK 细胞的靶标。体外试验发现,CIK 与 HBsAg 共培养,可以增强 CIK 细胞产生特异性杀伤作用。Gao 等[21]对 14 名慢性乙肝患者用 CIK 治疗 52 周后取得较好效果,其中有 6名(42.86%)患者肝功能恢复正常、血清 HBeAg 转阴。CIK 细胞用于临床治疗 CHB 的报道尚少,如进一步证实,可成为一个不错的治疗选项。

DC-CIK 细胞是树突状细胞(DC 细胞)与 CIK细胞共培养的产物。 DC 细胞是体内最重要的专业抗原递呈细胞,将抗原加工后通过 MHC 递呈到细胞表面刺激初始 T 细胞增殖,是诱导机体获得性免疫应答必不可少的环节。如上所述,由DC 细胞介导产生 HBV 特异 CTL,是清除 HBV的主要机制[22]。大量证据表明,DC 细胞与属于天然免疫的 CIK 细胞也有协同作用,导致 DCCIK 细胞毒性作用比 CIK 细胞更强,治疗效果也更好[23]。

有证据表明,CHB 患者 T 细胞应答不足,与 DC 功能缺陷导致抗原递呈功能低下有关。与健康人相比,CHB 患者外周血中的 DC 细胞数量较少,DC 表面共刺激分子 CD80、CD86 及主要组织相容性复合体 Ⅱ 类分子(MHC II)的表达显著降低,辅助 HBV 特异性的 CD8+T 细胞应答的能力降低,刺激 T 细胞增殖的能力也低于健康人[24-26]。基于 DC 细胞在 HBV 细胞免疫中的重要作用,已经有用诱导成熟的 DC 细胞作为过继性免疫治疗 CHB 的尝试。Chen 等[27]用 HBsAg刺激的 DC 治疗 19 例 CHB 患者,其中 10 名(52.6%)患者 HBeAg 转阴,这一结果与干扰素的疗效相当。这一研究结果如经过进一步证实,将有临床治疗价值。

3.3 阻断免疫抑制信号

机体不能对 HBV 产生正常的免疫反应,可能跟 CHB 患者的 T 细胞功能缺陷也有关系。已经发现,CHB 患者 HBV 特异的 CD8+T 细胞过度表达程序性死亡受体-1(Programmed Death Protein-1,PD-1)或程序性死亡配体-1(PD-1 Ligand,PD-L1),造成 T 细胞功能低下。PD-1/ PD-L1 系统是 T 细胞功能负调控机制之一,正常水平的 PD-1/PD-L1 可将 T 细胞功能维持在适度水平;如表达不足,T 细胞的功能过高,可致自身免疫反应;相反,表达过高,则可造成 T 细胞功能不足或缺失,导致肿瘤发生或感染持续。实验证明,在 PD-1/PD-L1 过表达造成 T 细胞功能缺失时,用抗体阻断 PD-1 与 PD-L1 相互作用可解除对 T 细胞的抑制作用,促进 T 细胞增殖,恢复对靶细胞的杀伤功能[28]。多个临床实验发现,部分肿瘤过度表达 PD-1/PD-L1,应用抗 PD-1 或抗 PD-L1 抗体,可恢复 T 细胞的抗癌功能,导致肿瘤消退,证明这个治疗策略的可行性。 近来,用抗 PD-1/PD-L1 抗体治疗 CHB 的研究取得了初步进展。Tzeng 等[28]利用抗 PD-1 抗体阻断PD-1 与 PD-L1 的作用,能上调 HBV 持续感染小鼠模型中肝内 T 细胞 HBcAg 特异性 IFN-γ 的产生,也能恢复 CTL 对病毒感染的清除作用,表明了抗 PD-1/PD-L1 抗体用于治疗 CHB 的潜在价值,但其疗效和安全性仍有待临床实验证明。

已发现的 T 细胞负调控分子机制还包括CD244、细胞毒 T 细胞相关蛋白-4(Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-Associated Protein 4,CTLA-4)和 T 细胞免疫球蛋白粘蛋白分子-3(T-cell immunoglobulin domain and mucin domain containing molecule-3,Tim-3)。与 PD-1 一样,CD244 在 CHB 患者 HBV 特异 CD8+T 细胞中过表达,通过不同的信号通路负调控 T 细胞免疫功能,因此阻断 CD244 和其配体 CD48 成为潜在的免疫疗法作用靶标而受关注[29]。CTLA-4 在肿瘤和病毒感染中的作用已有深入研究。有证据表明,阻断 CTAL-4 能促进 HBV 特异的 CD8+T 细胞增殖、诱导 Th1/Th2 应答产生、增强 CTL 杀伤效应[22,30,31]。临床上,抗 CTLA-4 抗体对多种肿瘤有明确的治疗作用,美国 FDA 已经批准抗CTLA-4 抗体治疗黑色素瘤[32],但该抗体药是否同样适用于 CHB 治疗仍有待进一步研究。Tim-3是近年来发现的另一种T细胞负调控机制,可能与 CHB 的发生有关。 在 CHB 患者体内观察到,高表达 Tim-3 的 T 细胞产生 IFN-γ 和 TNF-α 的能力减弱;Tim-3 阻断剂或抑制 Tim-3 的表达能促进HBV 特异 CD8+T 细胞增殖和细胞因子产生[33,34],增强 PBMC 和 NK 细胞的抗病毒作用[35]。

总之,已经发现多种免疫抑制蛋白在 CHB中对 T 细胞免疫起到抑制作用,因此应用这些分子的阻断剂(主要是单克隆抗体)来恢复 T 细胞抗HBV 的功能,已经成为 CHB 免疫疗法的一个研究热点。但这类蛋白对 T 细胞的抑制作用是免疫系统一种正常的调控机制,必不可少,如何使用抑制剂达到抗 HBV 的治疗效果而不使 T 细胞的功能失衡而导致严重副作用,是在实现临床应用之前必须解决的问题。因此,这类抑制剂的使用,还有很长的路要走,目前未见相关药品批准上市。

3.4 治疗性疫苗

目前已有多种治疗性疫苗经过临床试验。最常见的是针对表面抗原(HBsAg)或核心抗原(HBcAg)的常规疫苗。这些常规疫苗能实现血清 e 抗原(HBeAg)阴转、诱导 HBV 特异性免疫应答,也能降低病毒滴度,但是它们的有效期短暂,无法持续抑制 HBV 复制[36-42]。

分子生物学技术被用于设计复杂的治疗性疫苗,试图突破免疫耐受问题。例如,将 HBsAg和特异性 anti-HBs 抗体连接起来,组成了抗原-抗体复合物(Immunogenic Complex,IC)[43]。IC中的 Fc 段与 APC 膜表面受体结合,增加对抗原(HBsAg)的加工和递呈,同时还促进 Th1 细胞分泌 IFN-γ,从而诱发更强烈的细胞免疫反应。临床 I 期结果表明,IC 疫苗能导致部分 HBeAg 阳性病人发生 HBeAg 转阴,病人体内检测到 HBs抗体的表达、体内病毒载量也明显减少[44]。在随后的临床 II 期实验中,通过 IC 疫苗治疗,21.8%(17/78)的治疗组患者发生了 HBeAg 血清学转换,但是在治疗 24 周以后,这些患者体内仍能检测到少量病毒 DNA 和 HBsAg[45]。但是最新的临床 III 期试验发现 IC 组与安慰剂对照组差异不显著,跟临床 II 期结果相比,IC 组 HBeAg转阴率从 21.8% 降至 14%,而对照组则从 9% 升至 21.9%[3]。因此,这些结果不能证明 IC 疫苗具有长期治疗效果[3,4]。

由于 DNA 疫苗能较好地诱发 Th1 型细胞介导的细胞毒反应,而且比蛋白疫苗设计更简单、生产成本更低,因此 DNA 疫苗也成为了 CHB 免疫治疗的一种选择[46],一些表达 HBsAg 的 DNA疫苗也进入了临床 I 期试验。试验结果表明 DNA安全,且能恢复部分 T 细胞免疫,但是不足以显著抑制病毒复制[47,48]。因此,还没有治疗性 DNA疫苗进入市场。

4 合成免疫策略治疗慢性 HBV 感染

4.1 合成免疫抗 HBV 感染的基本原理

最近,我们提出了利用合成免疫治疗肿瘤的免疫疗法创新策略[49]:用微环 DNA 表达工程抗体,其中的单克隆抗体介导抗体依赖性细胞毒性作用,而双靶向抗体将非特异的 T 细胞转化为抗癌 CTL,两者协同,达到治疗癌症的目的。基于对急性感染康复过程以及对 CHB 发病机制的认识,我们提出用类似的合成免疫策略,来达到根治 CHB 的目的。这里描述 HBV 感染与肿瘤的差别,以及合成免疫实施方案的异同。

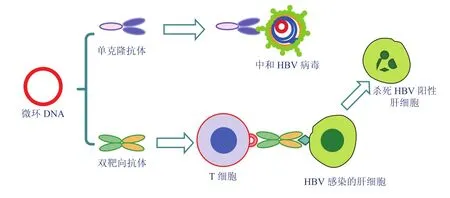

合成免疫抗 HBV 的策略是利用微环 DNA 合成并表达一组 HBV 特异的工程抗体(engineered Antibodies,eAbs),包括单克隆抗体(monoclonal Antibody,mAb)和双靶向抗体(BispecificAntibodies,BsAbs),用它们模拟急性 HBV 感染康复过程,由 mAb 中和病毒,而 BsAbs 在 T 细胞与感染 HBV 的肝细胞之间形成免疫突触,发挥 T 细胞受体一样的功能,介导 T 细胞杀死靶细胞(图 1)。

在预防 HBV 感染时,抗体中和病毒是主要的效应机制,但在清除 HBV 感染的过程中,抗体的作用有限。因为病毒生产大量 HBsAg 分泌到血液中,与中和抗体结合,成为病毒颗粒的保护伞。因此,急性 HBV 感染的康复,主要依靠 CTLs 清除 HBV 感染的靶细胞。相应地,抗HBV 合成免疫策略也应以 BsAb 介导 T 细胞杀伤感染肝细胞为主,辅以 mAb 中和体液中的病毒颗粒。

4.2 基于微环 DNA 技术的 HBV 合成免疫实施方案

工程抗体 BsAb 和 mAb 可以通过体外生产并纯化得到(基于抗体制备的免疫疗法),但抗体的制造成本高,且在体内的半衰期很短,难以用来建立起上述康复者体内持久的抗 HBV 免疫机制。这里提供了另一种抗 HBV 合成免疫的实施方案,即通过优化的非病毒 DNA 载体-微环 DNA(Minicircle,MC),在体内生产适量的抗HBV 工程抗体(mAb 及 BsAb)。MC 通过 DNA重组技术消除标准质粒载体中的骨架 DNA 成分,只含外源基因表达框[50,51]。骨架 DNA 成分包括质粒 DNA 复制起始位点、抗生素抗性基因和F1复制序列;它们只在DNA克隆时有用,在哺乳动物细胞中不但无用,还会产生多种不利作用,包括诱发转基因的沉默效应[52]和其富含的未甲基化 CpG 引起的炎症反应[53,54]。将这些成分去除后所得的 MC 载体,能在体内长期、稳定、高效地表达目的基因,对比普通标准质粒,优势明显[55]。当前,微环 DNA 的制备技术已经发展成熟,通过简单方法即可制备安全、无毒、高质量的医用级别 MC[56,57],并已逐渐被生物医学领域的研究者广泛应用。与基于抗体的免疫疗法相比,MC 具有明显优势,包括:

(1) 费用低廉

MC 的生产、纯化、储存和运送成本非常低廉,每一环节的费用都只是抗体技术的一小部分;

(2) 技术简单、灵活

更易于建立起多个 MC 组成的基因库,编码针对不同抗原表位的多种抗体;

图 1 合成免疫治疗慢性乙肝病毒感染。微环DNA表达工程抗体,其中单克隆抗体中和游离病毒,双靶向抗体介导非特异T细胞杀灭感染HBV的肝细胞,两者协同治疗CHBFig . 1 Anti-HBV synthetic immunity strategy. The minicircles are used to produce a goup of mAbs a nd BsAbs, the mAbs of which are to neutralize the viruses, while the BsAbs to retarget the resting T cells to become HBV-specific CTLs that is capable of killing HBV-infected hepatocytes

(3) 易于大量生产

MC 适于大批量生产,理论上能满足所有患者的需求;

(4) 安全性好

MC 本身不具有感染性,不会整合进患者基因组,十分安全。目前,FDA 已批准多种非病毒DNA 载体的商品化应用,也间接证明了 MC 的安全性。

制约 MC 大规模应用的主要因素是它的投递问题。然而,这一问题近期已经有所突破,已经有临床试验在评价体外和体内转染核酸技术的治疗效果[58-60]。比如,可利用 PBMC 或源于 PBMC的 DC-CIK 细胞作为 MC 的携带者,转染 MC 后回输到体内产生抗体。虽然 B 细胞是体内唯一生产抗体的细胞,但已经有多个报道表明,抗体可用转基因由皮肤或肌肉等细胞产生[61,62]。重要的是双靶向抗体只含有天然抗体的一小部分,与天然抗体有很大区别,具有转基因的基本特性[63-66]。基于该认识,笔者用 MC 转染人的 DCIK 细胞,生出产双靶向抗体(待发表资料)。本课题组已经合成了若干可生物降解的化合物,能在体内或体外高效介导微环 DNA 的转染,目前正在进一步优化。随着 DNA 投递技术的不断发展,投递已不再成为 MC 应用的制约因素。理想的治疗系统是,将微环 DNA 投送到如肝脏、肌肉一类的稳定的细胞群,长期表达抗 HBV 工程抗体,建立稳定的抗病毒机制。

总之,基于 MC 的合成免疫有望成为一个安全、高效、可负担的免疫治疗技术,可为攻克CHB 贡献力量。笔者已经初步证明这个设想的可行性,目前正在进一步完善这个治疗体系。

[1] WHO. Hepatitis B [OL]. [2015-03]. http://www. who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/.

[2] WHO. Guidelines for the Prevention, Care and Treatment of Persons with Chronic Hepatitis B Infection [M]. Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2015.

[3] Xu DZ, Wang XY, Shen XL, et al. Results of a phase III clinical trial with an HBsAg-HBIG immunogenic complex therapeutic vaccine for chronic hepatitis B patients: experiences and findings [J]. Journal of Hepatology, 2013, 59(3): 450-456.

[4] Liu J, Kosinska A, Lu M, et al. New therapeutic vaccination strategies for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B [J]. Virologica Sinica, 2014, 29(1): 10-16.

[5] Chisari FV, Ferrari C. Hepatitis B virus immunopathogenesis [J]. Annual Review Immunology, 1995, 13: 29-60.

[6] Milich DR, Jones JE, Hughes JL, et al. Is a function of the secreted hepatitis B e antigen to induce immunologic tolerance in utero? [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1990, 87(17): 6599-6603.

[7] Jung MC, Pape GR. Immunology of hepatitis B infection [J]. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2002, 2(1): 43-50.

[8] Bertoletti A, Kennedy PT. The immune tolerant phase of chronic HBV infection: new perspectives on an old concept [J]. Cellular & Molecular Immunology, 2015, 12(3): 258-263.

[9] Bertoletti A, Gehring AJ. Immune therapeutic strategies in chronic hepatitis B virus infection: virus or inflammation control? [J]. PLoS Pathogens, 2013, 9(12): e1003784.

[10] Moskophidis D, Lechner F, Pircher H, et al. Virus persistence in acutely infected immunocompetent mice by exhaustion of antiviral cytotoxic effector T cells [J]. Nature, 1993, 362(6422): 758-761.

[11] Seeger C, Mason WS. Molecular biology of hepatitis B virus infection [J]. Virology, 2015, 479-480C: 672-686.

[12] Thimme R, Wieland S, Steiger C, et al. CD8+T cells mediate viral clearance and disease pathogenesis during acute hepatitis B virus infection [J]. Journalof Virology, 2003, 77(1): 68-76.

[13] Lucifora J, Xia Y, Reisinger F, et al. Specific and nonhepatotoxic degradation of nuclear hepatitis B virus cccDNA [J]. Science, 2014, 343(6176): 1221-1228.

[14] Boni C, Fisicaro P, Valdatta C, et al.Characterization of hepatitis B virus(HBV)-specific T-cell dysfunction in chronic HBV infection [J]. Journal of Virology, 2007, 81(8): 4215-4225.

[15] Lau GK, Lok AS, Liang RH, et al. Clearance of hepatitis B surface antigen after bone marrow transplantation: role of adoptive immunity transfer [J]. Hepatology, 1997, 25(6): 1497-1501.

[16] Lau GK, Liang R, Lee CK, et al. Clearance of persistent hepatitis B virus infection in Chinese bone marrow transplant recipients whose donors were anti-hepatitis B core- and anti-hepatitis B surface antibody-positive [J]. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 1998, 178(6): 1585-1591.

[17] Lau GK, Suri D, Liang R, et al. Resolution of chronic hepatitis B and anti-HBs seroconversion in humans by adoptive transfer of immunity to hepatitis B core antigen [J]. Gastroenterology, 2002, 122(3): 614-624.

[18] Ilan Y, Nagler A, Zeira E, et al. Maintenance of immune memory to the hepatitis B envelope protein following adoptive transfer of immunity in bone marrow transplant recipients [J]. Bone Marrow Transplantion, 2000, 26(6): 633-638.

[19] Chen PM, Chiou TJ, Fan FS, et al. Fulminant hepatitis is significantly increased in hepatitis B carriers after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation [J]. Transplantation, 1999, 67(11): 1425-1433.

[20] Caselitz M, Link H, Hein R, et al. Hepatitis B associated liver failure following bone marrow transplantation [J]. Journal of Hepatology, 1997, 27(3): 572-577.

[21] 高燕, 魏来, 陈红松, 等. 免疫活性细胞回输法治疗慢性乙型肝炎不引起肝组织损害 [J]. 中华肝脏病杂志, 2003, 11(7): 391-393.

[22] Wang L, Zou ZQ, Liu CX, et al. Immunotherapeutic interventions in chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a review [J]. Journal of Immunological Methods, 2014, 407: 1-8.

[23] Ma YJ, He M, Han JA, et al. A clinical study of HBsAg-activated dendritic cells and cytokineinduced killer cells during the treatment for chronic hepatitis B [J]. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology, 2013, 78(4): 387-393.

[24] Wang FS, Xing LH, Liu MX, et al. Dysfunction of peripheral blood dendritic cells from patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection [J]. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 2001, 7(4): 537-541.

[25] Duan XZ, Wang M, Li HW, et al. Decreased frequency and function of circulating plasmocytoid dendritic cells(pDC) in hepatitis B virus infected humans [J]. Journal of Clinical Immunology, 2004, 24(6): 637-646.

[26] 王福生, 张纪元. HBV 感染免疫应答和免疫治疗新进展 [J]. 传染病信息, 2011, 24(4): 193-198.

[27] Chen M, Li YG, Zhang DZ, et al. Therapeutic effect of autologous dendritic cell vaccine on patients with chronic hepatitis B: a clinical study [J]. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 2005, 11(12): 1806-1808.

[28] Tzeng HT, Tsai HF, Liao HJ, et al. PD-1 blockage reverses immune dysfunction and hepatitis B viral persistence in a mouse animal model [J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(6): e39179.

[29] Raziorrouh B, Schraut W, Gerlach T, et al. The immunoregulatory role of CD244 in chronic hepatitis B infection and its inhibitory potential on virus-specific CD8+T-cell function [J]. Hepatology, 2010, 52(6): 1934-1947.

[30] Yu Y, Wu H, Tang Z, et al. CTLA4 silencing with siRNA promotes deviation of Th1/Th2 in chronic hepatitis B patients [J]. Cellular & Molecular Immunology, 2009, 6(2): 123-127.

[31] Schurich A, Khanna P, Lopes AR, et al. Role of the coinhibitory receptor cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 on apoptosis-Prone CD8 T cells in persistent hepatitis B virus infection [J]. Hepatology, 2011, 53(5): 1494-1503.

[32] Ledford H. Melanoma drug wins US approval [J]. Nature, 2011, 471: 561-561.

[33] Wu W, Shi Y, Li S, et al. Blockade of Tim-3 signaling restores the virus-specific CD8+T-cell response in patients with chronic hepatitis B [J]. European Journal of Immunology, 2012, 42(5): 1180-1191.

[34] Nebbia G, Peppa D, Schurich A, et al. Upregulation of the Tim-3/galectin-9 pathway of T cell exhaustion in chronic hepatitis B virus infection [J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(10): e47648.

[35] Ju Y, Hou N, Meng J, et al. T cell immunoglobulinand mucin-domain-containing molecule-3 (Tim-3) mediates natural killer cell suppression in chronic hepatitis B [J]. Journal of Hepatology, 2010, 52(3): 322-329.

[36] Couillin I, Pol S, Mancini M, et al. Specific vaccine therapy in chronic hepatitis B: induction of T cell proliferative responses specific for envelope antigens [J]. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 1999, 180(1): 15-26.

[37] Dikici B, Bosnak M, Ucmak H, et al. Failure of therapeutic vaccination using hepatitis B surface antigen vaccine in the immunotolerant phase of children with chronic hepatitis B infection [J]. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2003, 18(2): 218-222.

[38] Jung MC, Gruner N, Zachoval R, et al. Immunological monitoring during therapeutic vaccination as a prerequisite for the design of new effective therapies: induction of a vaccine-specific CD4+T-cell proliferative response in chronic hepatitis B carriers [J]. Vaccine, 2002, 20(29-30): 3598-3612.

[39] Pol S, Nalpas B, Driss F, et al. Efficacy and limitations of a specific immunotherapy in chronic hepatitis B [J]. Journal of Hepatology, 2001, 34(6): 917-921.

[40] Ren F, Hino K, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Cytokinedependent anti-viral role of CD4-positive T cells in therapeutic vaccination against chronic hepatitis B viral infection [J]. Journal of Medical Virology, 2003, 71(3): 376-384.

[41] Safadi R, Israeli E, Papo O, et al. Treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection via oral immune regulation toward hepatitis B virus proteins [J]. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 2003, 98(11): 2505-2515.

[42] Yalcin K, Acar M, Degertekin H. Specific hepatitis B vaccine therapy in inactive HBsAg carriers: a randomized controlled trial [J]. Infection, 2003, 31(4): 221-225.

[43] Wen YM, Wu XH, Hu DC, et al. Hepatitis B vaccine and anti-HBs complex as approach for vaccine therapy [J]. The Lancet, 1995, 345(8964): 1575-1576.

[44] Yao X, Zheng B, Zhou J, et al. Therapeutic effect of hepatitis B surface antigen-antibody complex is associated with cytolytic and non-cytolytic immune responses in hepatitis B patients [J]. Vaccine, 2007, 25(10): 1771-1779.

[45] Xu DZ, Zhao K, Guo LM, et al. A randomized controlled phase IIb trial of antigen-antibody immunogenic complex therapeutic vaccine in chronic hepatitis B patients [J]. PLoS One, 2008, 3(7): e2565.

[46] Pol S, Michel ML. Therapeutic vaccination in chronic hepatitis B virus carriers [J]. Expert Review Vaccines, 2006, 5(5): 707-716.

[47] Mancini-Bourgine M, Fontaine H, Scott-Algara D, et al. Induction or expansion of T-cell responses by a hepatitis B DNA vaccine administered to chronic HBV carriers [J]. Hepatology, 2004, 40(4): 874-882.

[48] Mancini-Bourgine M, Fontaine H, Brechot C, et al. Immunogenicity of a hepatitis B DNA vaccine administered to chronic HBV carriers [J]. Vaccine, 2006, 24(21): 4482-4489.

[49] Chen ZY, Ma F, Huang H, et al. Synthetic immunity to break down the bottleneck of cancer immunotherapy [J]. Science Bulletin, 2015, 60(11): 977-985.

[50] Darquet AM, Cameron B, Wils P, et al. A new DNA vehicle for nonviral gene delivery: supercoiled minicircle [J]. Gene Therapy, 1997, 4(12): 1341-1349.

[51] Bigger BW, Tolmachov O, Collombet JM, et al. An araC-controlled bacterial cre expression system to produce DNA minicircle vectors for nuclear andmitochondrial gene therapy [J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2001, 276(25): 23018-23027.

[52] Chen ZY, Riu E, He CY, et al. Silencing of episomal transgene expression in liver by plasmid bacterial backbone DNA is independent of CpG methylation [J]. Molecular Therapy, 2008, 16(3): 548-556.

[53] Chen ZY, He CY, Ehrhardt A, et al. Minicircle DNA vectors devoid of bacterial DNA result in persistent and high-level transgene expression in vivo [J]. Molecular Therapy, 2003, 8: 495-500.

[54] Dietz WM, Skinner NE, Hamilton SE, et al. Minicircle DNA is superior to plasmid DNA in eliciting antigen-specific CD8+T-cell responses [J]. Molecular Therapy, 2013, 21(8): 1526-1535.

[55] Stenler S, Blomberg P, Smith CI. Safety and efficacy of DNA vaccines: plasmids vs. minicircles [J]. Human Vaccines Immunotherapeutics, 2014, 10(5): 1306-1308.

[56] Jechlinger W, Azimpour Tabrizi C, Lubitz W, et al. Minicircle DNA immobilized in bacterial ghosts: in vivo production of safe non-viral DNA delivery vehicles [J]. Journal of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2004, 8(4): 222-231.

[57] Kay MA, He CY, Chen ZY. A robust system for production of minicircle DNA vectors [J]. Nature Biotechnology, 2010, 28: 1287-1289.

[58] Zhao Y, Moon E, Carpenito C, et al. Multiple injections of electroporated autologous T cells expressing a chimeric antigen receptor mediate regression of human disseminated tumor [J]. Cancer Research, 2010, 70(22): 9053-9061.

[59] Bhang HE, Gabrielson KL, Laterra J, et al. Tumorspecific imaging through progression elevated gene-3 promoter-driven gene expression [J]. Nature Medicine, 2011, 17(1): 123-129.

[60] Barrett DM, Zhao Y, Liu X, et al. Treatment of advanced leukemia in mice with mRNA engineered T cells [J]. Human Gene Therapy, 2011, 22(12): 1575-1586.

[61] Perez N, Bigey P, Scherman D, et al. Regulatable systemic production of monoclonal antibodies by in vivo muscle electroporation [J]. Genetic Vaccines and Therapy, 2004, 2(1): 2.

[62] Noel D, Pelegrin M, Kramer S, et al. High in vivo production of a model monoclonal antibody on adenoviral gene transfer [J]. Human Gene Therapy, 2002, 13(12): 1483-1493.

[63] You XJ, Yang J, Gu P, et al. Feline neural progenitor cells II: use of novel plasmid vector and hybrid promoter to drive expression of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor transgene [J]. Stem Cells International, 2012: 604982. doi: 10.1155/2012/604982.

[64] Kymalainen H, Appelt JU, Giordano FA, et al. Long-term episomal transgene expression from mitotically stable integration-deficient lentiviral vectors [J]. Human Gene Therapy, 2014, 25(5): 428-442.

[65] Mizutani A, Kikkawa E, Matsuno A, et al. Modified S/MAR episomal vectors for stably expressing fluorescent protein-tagged transgenes with small cell-to-cell fluctuations [J]. Analytical Biochemistry, 2013, 443(1): 113-116.

[66] Lufino MM, Popplestone AR, Cowley SA, et al. Episomal transgene expression in pluripotent stem cells [J]. Methods in Molecular Biology, 2011, 767: 369-387.

Perspectives on Synthetic Immunity to Treat Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection

CHEN Ping HE Chengyi CHEN Zhiying

(Laboratory for Gene and Cell Engineering,Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology,Chinese Academy of Sciences,Shenzhen518055,China)

Chronic infection of hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a severe public health problem because it affects millions of people worldwide and results in 600 thousand deaths from liver cirrhosis and hepatocarcinoma each year. Currently, no treatment is available to cure this disease. Here, we propose a synthetic immunity strategy to treat this disease. Specifically, minicircle DNA, an optimized non-viral vector, is used to express a group of engineered antibodies, of which the monoclonal antibodies act to neutralize the virus, while the bispecific antibodies (BsAbs) to render the resting T lymphocytes the function of anti-HBV CTLs to eliminate HBV-infected hepatocytes. The two classes of antibodies work in concert to cure the disease as the host immune system eliminates the virus during recovering from acute infection. With the superior features in safety, transgene expression profile and cost-effectiveness, minicircle can be used to establish a powerful anti-HBV synthetic immunity to achieve this goal.

Hepatitis B virus; chronic HBV infection; synthetic immunity; minicircle DNA; adoptive immunity

Q 812

A

2015-05-15

:2015-06-01

深圳市政府基金(SFG 2012.566 和 SKC 2012.237)

谌平,博士,研究方向为 HBV 免疫治疗;何成宜,高级工程师,研究方向为基因与细胞治疗技术;陈志英(通讯作者),研究员,研究方向为基因与免疫细胞治疗,E-mail:zy.chen1@siat.ac.cn。