Imperfect targeted advertising with two-period competition

Zou Xiang Zhong Weijun Mei Shu’e

(School of Economics and Management, Southeast University, Nanjing 211189, China)

Imperfect targeted advertising with two-period competition

Zou Xiang Zhong Weijun Mei Shu’e

(School of Economics and Management, Southeast University, Nanjing 211189, China)

A two-period model is developed to investigate the competitive effects of targeted advertising with imperfect targeting in a duopolistic market. In the first period, two firms compete in price in order to recognize customers. In the second period, targeted advertising plays an informative role and acts as a price discrimination device. The firms’ optimal advertising and pricing strategies under imperfect targeting are compared with those under perfect targeting. Equilibrium decisions show that, under imperfect targeting, when the advertising cost is low enough, both firms will choose to target ads at the rivals’ old segments. This equilibrium, which could not exist under perfect targeting, results in two opposite results. When cost is high, the effect of mis-targeting will soften price competition and increase profits; on the contrary, when cost is low enough, it will lead to aggressive price competition and profit loss with the increase of imperfect targeting, so firms may have incentives to reduce the mis-targeting degree.

targeted advertising; imperfect targeting; price discrimination; two-period game

Targeted advertising, as a new marketing approach, can target advertising to specific segments of consumers within a market. To date, much research has assumed that acquired data about consumer preferences and purchasing behavior are accurate and credible. However, in practice, because of personal and objective reasons, the data may not be accurate and cannot reflect the real attributes of individual consumers. This means that a firm’s targeting based on previous purchase history is imperfect. In this paper, we investigate the competitive implications of this kind of imperfect targeting.

A two-period game is established to examine the targeted advertising with imperfect targeting. For example, when a new or upgraded product is introduced to the market, two firms compete in price during the first period which is the firm’s data collecting and consumer recognition process. Through consumers’ price choices, the market is segmented, so firms acquire the ability to send targeted advertising and price discrimination over the next period. The key feature of this paper is that the acquired data after period 1 is assumed to be imperfect, which will result in different conclusions compared with perfect targeting.

Many previous works stress the positive effects of targeted advertising, such as profit increases and price competition mitigation[1-7].However, some research suggests that in certain circumstances,targeted advertising will play a negative role and result in aggressive competition, even profit loss[8-9]. Another stream of work related to our paper is behavior-based price discrimination and consumer recognition[10-12]. Our present work combines targeted advertising with price discrimination in which advertising is used as a price discrimination device[13]. In addition, in all of these papers above, consumers are perfectly segmented. This means that there is no mis-targeting between different groups.

This paper was inspired by the research on imperfect targetability which received limited attention in previous research. Chen et al.[14]provided the first rigorous analysis of individual marketing with imperfect targetability, but they only focused on targeted price. In this paper, we highlight the importance of advertising which acts as a price discrimination device. Iyer et al.[5]also paid attention to the leakage of targeted advertising and found that increasing leakage reduces the equilibrium profits. But Chen and Iyer et al. ignored the data collecting and consumer recognition process, which is the first step of behavior-based targeted advertising and price discrimination.

1 Assumptions

Consider a market consisting of two risk-neutral firms, denoted by A, B. Each firmiproduces a homogeneous product but different brands to end consumers at a constant marginal production cost, which is, without loss of generality, normalized to zero. Firms do not incur any other cost for marketing except the advertising cost (in this paper,i,j=A,B,i≠j).

On the demand side, every customer buys at most one unit of goods in each period and has a common reservation pricer. To depict the heterogeneity of customers, following Varian et al.[15-16],we assume that there are three segments in the market. First, each firm has its loyal customers with identical sizeαwho are price-insensitive shoppers and purchase only from the firm as long as the charged price is belowr. The rest consumers are price-sensitive comparison buyers with sizeβ, and they switch between two brands according to the lowest price. The total number of customers is normalized to 1, so we have 2α+β=1,β∈(0,1) andα∈(0,1/2).

Suppose that advertising plays an informative role and acts as a price discrimination device. According to Ref.[5], advertising cost is linearly related to the advertised segment size. So the expenditure for the entire market isc, to the loyal segment and comparison segment areαc,βc, respectively.

Firms are expected to maximize profit and behave non-cooperatively, taking the rival’s strategy into account. The size of each segment is common knowledge to both firms, but an individual’s specific type is a “mystery”. In period 1, firms simultaneously set uniform prices. The firm with the lower price will attract all the switchers and thus lose the ability to distinguish between its own loyal consumers and switchers, at the same time, has no choice but to charge a uniform price in period 2. On the contrary, the firm with the higher price only sells to its loyal segment, so it can recognize these loyal customers and charge two prices in period 2: one for the identified segment, the other for the rest of the market which has not been identified. Through price competition and consumers’ own choice, customer recognition will be achieved at the end of period 1. In period 2, they decide their advertising and pricing strategies.

2 Benchmark Case

We start by establishing the benchmark case where consumer recognition based on price competition of period 1 is dependable and accurate. This benchmark case will help us isolate the competitive effect of imperfect targeting. Backward induction is used to derive the equilibrium.

2.1 Equilibrium in the second period

S1: Both firms target ads only to their old segment.

S2: Firm A targets the old segment; Firm B chooses the entire market.

S3: Firm A does not advertise; Firm B only targets the old segment.

S4: Firm A does not advertise; Firm B chooses the entire market.

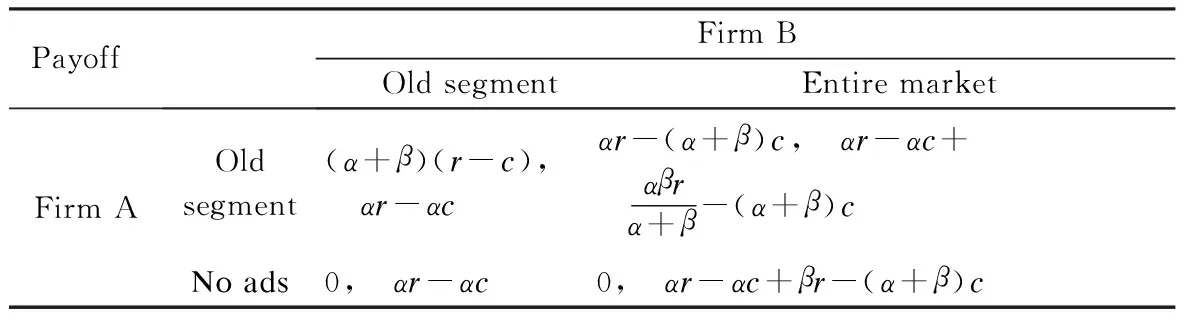

The payoffs of the four subgames are shown in Tab.1. The results of S1, S3 and S4 are obvious, and the detailed computation of S2 follows Narasimhan[16].

Tab.1 The payoff matrix under perfect targeting

2.2 Equilibrium in the first period

When making pricing decisions in period 1, firms rationally anticipate that their strategies will affect the profits in the second period. Similar to the previous analysis, a mixed symmetric equilibrium exists. A rational firm will make the choice to maximize the total profits of two periods. Denote the equilibrium distribution functionFi1(p) as the possibility that firmi’s price is lower thanpin period 1. In the symmetric equilibrium whereFi1(p)=Fj1(p)=F1(p), each firm’s two-period expected profit which is denoted byπiis

πi=[α+(1-Fj1(pi1))β]pi1+[(1-Fj1(pi1))πA2+Fj1(pi1)πB2]pi1∈[p1min,p1max]

(1)

(2)

Proposition 3 With perfect targeting, in period 1, firms set prices according to

(3)

Each firm’s two-period profits are given by

(4)

3 Targeted Advertising with Imperfect Targeting

Consumer recognition of period 1 is a process to make consumers endogenously segmented into different groups. This classification is assumed to be accurate in the benchmark case, but in practice, it is always a less-than-perfect probability. This means that firms’ perceived consumer segmentation differs from the actual situation. For example, the customer happens to purchase only when the firm offers promotions or when he/she receives coupons.

3.1 Equilibrium in the second period

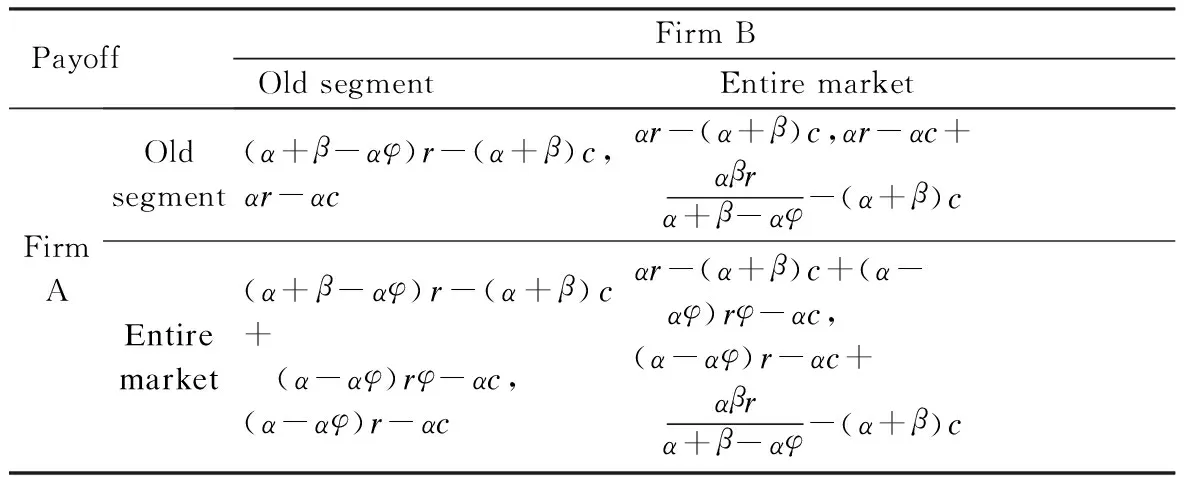

Due to imperfect targeting, the advertising and pricing strategies will be affected. Advertising plays an informative role and can target particular segments. So for Firm B, it is profitable to advertise to the old segment (including parts of B’s loyal consumers and some switchers), and it also has a choice of the new part consisting of A’s loyal consumers, parts of switchers and some of B’s loyal consumers. Firm A, compared to the basic case that it definitely does not target a new segment, in the case of being imperfect, there is some probability for it to advertise to new segment for pursuing the mistaken switchers in B’s old segment. Thus, there are also 2×2 subgames. The results are shown in Tab.2

S1: Both firms target their old segment.

S2: Firm A targets the old segment; Firm B chooses the entire market.

S3: Firm A advertises to the entire market; Firm B only targets the old segment.

S4: Both firms choose the entire market.

Tab.2 The payoff matrix under imperfect targeting

3.2 Equilibrium in the first period

(5)

(6)

Proposition 6 With imperfect targeting, in period 1, firms set prices according to

(7)

Each firm’s two-period profits are given by

(8)

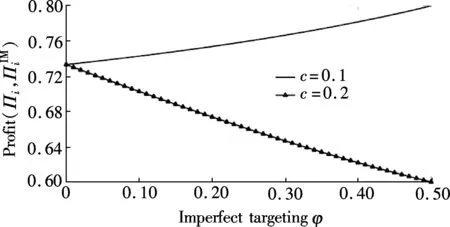

4 Competitive Effects of Imperfect Targeting

From the analysis above, firms’ strategies in the second period will be changed because of imperfect targeting. In that case, firms may have an incentive to distort their first-period behavior for the adjustment in period 2. At the same time, there is some impact on total profit.

4.1 First-period prices

Proposition 7 When the advertising cost is high, the mis-targeting effect can soften price competition. However, when the cost is low, an aggressive price competition will arise with the increase ofφ, and qualitatively change the incentive environment.

When the advertising cost is high and two firms can only target their old segments, the increase of the mis-targeting extentφunder imperfect targeting results in a great profit loss to the low price firm in period 1, in that case, forward looking firms have an incentive to raise prices in order to avoid the profit loss in the next period. When the advertising cost is lower and only the high price firm of period 1 is beneficial to target the rival’s segment, the firm can obtain more profits resulting from extra switchers as loyal consumers under imperfect targeting, so the support of prices and the average price will be higher. If the advertising cost is low enough, the mis-targeting will cause two firms to compete in each other’s old segment which does not exist under perfect targeting. We know that, in S2 under perfect targeting, the profit of the high-price firm is always larger than that of the low-price firm, so the price competition is mitigated. In comparison with that, under imperfect targeting, the higherφ, the more benefit for low-price firms in period 1,which encourages two firms to reduce prices. So an aggressive price competition will arise; meanwhile this situation will make the high-price firm of period 1 reduce the error rate or increase targetability. This conclusion can also be explained by Proposition 3 and Proposition 5.

Fig.1 Cumulative distribution functions for prices under perfect and imperfect targeting

4.2 Profits

Fig.2 Profits as a function of cost c under imperfect and perfect targeting

Fig.3 Profits as a function of imperfect targeting φ

5 Conclusion

This paper compares the firms’ optimal advertising and pricing strategies under imperfect targeting with those under perfect targeting. A two-period model is developed to investigate the competitive effects of imperfect targeting in a duopolistic market. Results show that: 1) The existence of imperfect targeting results in an additional conclusion compared to perfect targeting; that is when the advertising cost is low enough, two firms competing with each other in the rivals’ segment. 2) The mis-targeting effect can soften price competition and increase profit when the advertising cost is high enough, which is consistent with Chen’s results; however, when the cost is low enough, an aggressive price competition and profit loss will arise with the increase of mis-targeting. So firms may have incentives to reduce the mis-targeting degree.

[3]Johnson J P. Targeted advertising and advertising avoidance [J].RANDJournalofEconomics, 2013, 44(1): 128-144.

[4]Roy S. Strategic segmentation of a market [J].InternationalJournalofIndustrialOrganization, 2000, 18(8):1279-1290.

[5]Iyer G, Soberman D, Villas-Boas J M. The targeting of advertising [J].MarketingScience, 2005, 24(3): 461-476.

[7]Esteves R B, Resende J. Competitive targeted advertising with price discrimination [R]. Portugal: University of Minho, 2013.

[8]Gal-Or E, Gal-Or M, May J H, et al. Targeted advertising strategies on television [J].ManagementScience, 2006, 52(5): 713-725.

[9]Brahim N Ben Elhadj-Ben, Lahmandi-Ayed R, Laussel D. Is targeted advertising always beneficial? [J].InternationalJournalofIndustrialOrganization, 2011, 29(6): 678-689.

[10]Fudenberg D, Villas-Baos J M. Behavior-based price discrimination and customer recognition [C]//EconomicsandInformationSystems. Amsterdam, Holland: Elsevier, 2007: 1-78.

[11]Esteves R B. Pricing with customer recognition [J].InternationalJournalofIndustrialOrganization, 2010, 28(6): 669-681.

[12]Chen Y, Zhang Z J. Dynamic targeted advertising with strategic consumers [J].InternationalJournalofIndustrialOrganization, 2009, 27(1): 43-50.

[13]Zhang J Q, Zhong W J, Mei S E. A model of targeted advertising with consumer recognition [J].JournalofSoutheastUniversity:EnglishEdition, 2012, 28(4):490-495.

[14]Chen Y, Narasimhan C, Zhang Z J. Individual marketing with imperfect targetability [J].MarketingScience, 2001, 20(1): 23-41.

[15]Varian H R. A model of sales [J].AmericanEconomicReview,1980,70(4): 651-659.

[16]Narasimhan C. Competitive promotional strategies [J].JournalofBusiness, 1988, 61(4): 427-449.

不完美定向广告的两阶段竞争模型

邹 翔 仲伟俊 梅姝娥

(东南大学经济管理学院,南京211189)

研究了双寡头市场条件下,基于不完美定向的定向广告竞争模型.通过两阶段博弈来描述新产品或升级产品引入时不完美定向对企业广告及定价决策带来的影响.第一阶段通过价格竞争辨识消费者,第二阶段广告作为传递产品信息和价格歧视的工具.比较分析不完美定向与完美定向情况下企业的广告和定价策略,均衡结果显示:在不完美定向条件下,当广告成本足够低时,会出现在完美定向情境下不可能出现的均衡,即两企业均会选择向对方的优势市场投入广告.这一均衡的存在会导致2种相反的结果:当广告成本较高时,不完美定向能缓和价格竞争并增加企业利润;但当广告成本足够低时,随着不完美定向程度的增加,反而会加剧市场竞争并导致企业利润损失,因此,企业有动机降低定向误差的程度.

定向广告;不完美定向;价格歧视;两阶段博弈

F270.5

The National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.71371050).

:Zou Xiang, Zhong Weijun, Mei Shu’e. Imperfect targeted advertising with two-period competition[J].Journal of Southeast University (English Edition),2014,30(3):374-379.

10.3969/j.issn.1003-7985.2014.03.022

10.3969/j.issn.1003-7985.2014.03.022

Received 2014-02-23.

Biographies:Zou Xiang(1986—), female, graduate; Zhong Weijun (corresponding author), male, doctor, professor, zhongweijun@seu.edu.cn.

Journal of Southeast University(English Edition)2014年3期

Journal of Southeast University(English Edition)2014年3期

- Journal of Southeast University(English Edition)的其它文章

- P-FFT and FG-FFT with real coefficients algorithm for the EFIE

- Compressed sensing estimation of sparse underwateracoustic channels with a large time delay spread

- Improved metrics for evaluating fault detection efficiency of test suite

- Early-stage Internet traffic identification based on packet payload size

- An adaptive generation method for free curve trajectory based on NURBS

- Stability analysis of time-varying systems via parameter-dependent homogeneous Lyapunov functions