大蒜活性成分与硫化氢的关系研究

李新霞, 赵东升, 耿 晶, 张海波, 陈 坚

(1新疆医科大学药学院, 乌鲁木齐 830011; 2新疆埃乐欣药业有限公司, 乌鲁木齐 830013)

大蒜为多年生百合科葱属植物蒜(AlliumSativumL.)的地下鳞茎,在世界各地的使用已有几百年的历史,大蒜的抗真菌、抗细菌和抗病毒的特性早已为人熟知。现代研究发现大蒜对死亡率最高的心脑血管疾病及肿瘤等有防治功效,多个学科从不同角度用现代的方法研究这一古老的药食兼用植物[1]。目前公认大蒜的主要活性成分为其含硫化合物,本文就大蒜含硫活性成分及体内代谢、大蒜含硫化合物与硫化氢(H2S)的关系、H2S检测方法及H2S供体药物的研究进展综述如下。

1 大蒜含硫活性成分及体内代谢

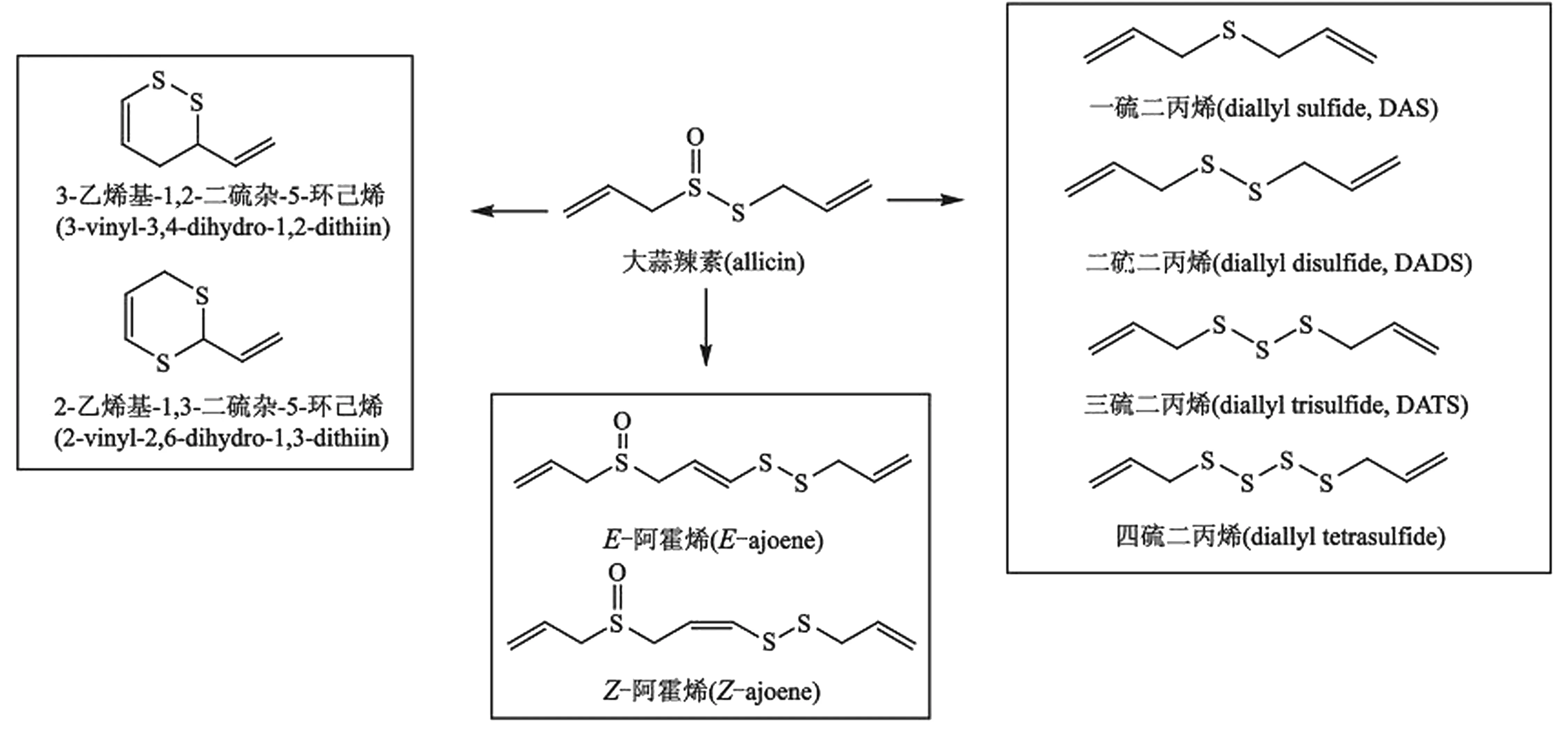

1.1蒜氨酸与大蒜辣素为大蒜的活性成分蒜氨酸(Alliin)为大蒜中标志性含硫氨基酸,化学名为S-烯丙基-L-半胱氨酸亚砜[(+)S-allyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide],天然存在的蒜氨酸为右旋构型,存在于大蒜植物细胞的溶质中。蒜氨酸在大蒜中的含量占0.5%~2.0%(鲜重),因生长环境而异。蒜酶(Allinase)又称蒜氨酸裂解酶(Aliin lyase) (EC 4.4.1.4),是5’-磷酸吡哆醛依赖酶,大蒜中的蒜酶亚单位有448个氨基酸,分子量约51 500 u[2]。 蒜酶与蒜氨酸分处大蒜植物细胞不同的隔室,二者在研碎时接触,快速反应产生大蒜辣素(图1)。大蒜辣素(Allicin)化学名为二丙烯基硫代亚磺酸酯(diallyl thiosulfinate),在完整无损大蒜中并不存在大蒜辣素,只有当大蒜被切开或碾碎后前体物质蒜氨酸与大蒜中的蒜酶接触后瞬时发生催化反应,才生成大蒜辣素(图1)。大蒜辣素不稳定,在不同条件下可进一步分解产生系列含硫的活性物质,研究较多的为较大蒜辣素稳定性的降解产物,如二烯丙基单硫化合物(diallyl sulfide,DAS)、二烯丙基二硫化合物(diallyl disulfide,DADS)、二烯丙基三硫化合物(diallyl trisulfide, DATS)等(图2),因此大蒜辣素被称为含硫活性物质的母体(mother compound)[3]。

图1 蒜酶催化蒜氨酸产生大蒜辣素

1.2大蒜含硫化合物代谢产物有关大蒜中含硫化合物活性作用的研究报道较多,但对其作用机制和代谢的研究报道很少,且多集中于DAS、DADS、DATS等二烯丙基硫化物[4],单硫化合物(DAS)在组织中经序列氧化,形成亚砜(sulfoxide)后继续氧化为砜(sulfone)[5-6],并迅速与细胞内的抗氧化剂谷胱甘肽结合[7]。二硫化物DADS在鼠肝脏代谢为烯丙基硫醇(allyl mercaptan, AM)、烯丙基甲基硫化物(allyl methyl sulfide,AMS)[8-9]、烯丙基甲基亚砜(allyl methyl sulfoxide,AMSO)和烯丙基甲基砜(allyl methyl sulfone,AMSO2)[10]。

大蒜含硫半胱氨酸类似物的代谢可形成S-巯基结合物(S-mercapto conjugates),且S-烯丙基硫醇(S-allyl mercaptan, SAMC)和S-烯丙基半胱氨酸(S-allylcysteine, SAC)是大鼠肝脏匀浆中β-裂解酶-γ-胱硫醚酶(cystathionineylyase cystathionase, CSE)的底物[9]。

众多研究报道中,有关大蒜辣素及其降解产物的活性作用的文献很多,但只有部分较为稳定的大蒜辣素降解产物如DADS、DATS等的代谢情况有研究报道,真正到达靶组织的物质或代谢产物是什么还不清楚,但已有的信息显示,这些化合物的代谢速度非常快[10-11]。但蒜氨酸与大蒜辣素在体内代谢途径和作用机制还不十分清楚。

图2 大蒜辣素在不同条件下可转化为系列含硫化合物

2 大蒜含硫化合物与H2S的关系研究进展

2.1内源性H2S的产生H2S是继一氧化氮(NO)和一氧化碳(CO)之后发现的第3种气体信使分子(Gastransmiter),在生理pH 7~8条件下,约4/5的H2S主要以HS-阴离子的形式存在,约1/5以H2S的形式存在,另外还有痕量的S2-,目前文献研究所指的H2S是3种形式的总和。H2S在脂溶性溶剂中的溶解性是水中的5倍,能够自由通过细胞膜。

H2S在哺乳动物体内的产生可通过酶系统或非酶系统2条途径,胱硫醚-γ-裂解酶(Cystathionine-γ-lyase,CSE)和胱硫醚-β-合酶(cystathionine-β-synthase ,CBS)是体内转硫化作用途径的2个关键酶。CSE和CBS遍布全身各组织,包括心血管系统、神经系统和胃肠道系统。CBS催化半胱氨酸等含硫氨基酸产生H2S,CSE可将胱氨酸转化为半胱氨酸、H2S、铵盐和丙酮酸盐;在细胞内还原剂存在下3-MPST可催化硫烷硫而产生H2S;线粒体内的天冬氨酸氨基转移酶(aspartate aminotransferase,AAT)可将半胱氨酸转化为3-巯基丙酮酸(3-mercaptopyruvate)和铵盐之后 3-MPST将3-巯基丙酮酸转化为丙酮酸盐和H2S[12-13]。除了经由酶系统途径外,还有一种非酶途径可以释放H2S,即从细胞内“酸-不稳定硫储库(acid-labile sulfur pool)”中释放,如硫烷硫(sulfane sulfur),而DADS、DAT、DATS释放H2S的途径可能都与此途径有关[14]。

2.2大蒜硫化学的研究进展大蒜的活性成分是一系列的含硫化合物,生物学家试图将大蒜含硫化合物的生物活性作用与体内H2S的产生联系在一起。首先,2003年Biteau等[15]在酵母中发现了蛋白硫氧化还原素,之后在人体内也发现了这种蛋白。这种蛋白可将过氧化物酶基因中的半胱亚磺酸(cysteine sulfinic acid)还原为半胱次磺酸( cysteine sulfenic acid)。与此同时,Giles等[16]在2001-2003年提出一个新的概念——活性硫类(reactive sulfur species, RSS),研究意外发现体内硫的氧化还原化学反应,对人们理解RSS在人体内的生物化学和细胞内氧化还原信号传导和控制的作用具有重要影响。其次,2003年,Munday等[17]的研究显示,与大蒜相关生物学活性多硫化合物的化学比之前的研究要复杂得多,如多硫化合物可被催化产生超氧自由基,从而调节细胞内的氧化还原状态,如氧化还原信号传导、细胞凋亡和抗癌研究。

2.3大蒜衍生含硫化合物活性作用与H2S的关系2007年几乎同时发表的文章将大蒜与H2S的释放联系在了一起。2007年4月德国的Munchberg等[18]提出大蒜含硫化合物有可能释放硫化氢。随后相继有关于大蒜的含硫化合物与H2S的关系报道[19-20]。

2.3.1 大蒜辣素降解产物的生物学活性作用 Benavides等[19]报道DADS与DATS释放硫化氢的数据,提出体内的血管舒张活性作用可能是由H2S介导产生的,并通过体外实验验证了有机硫化合物通过与红细胞作用直接产生H2S;含硫化合物可以穿过细胞膜与细胞内的GSH反应,因此认为大蒜含硫化合物可以被细胞内任何含有巯基化合物诱导产生H2S,H2S经扩散作用通过质膜引起平滑肌细胞舒张。研究还发现,源于大蒜的含硫化合物含有较多的烯丙基和硫原子,有助于该化合物生成H2S。

2.3.2 半胱氨酸及同系物的生物活性作用 2007年Chuah等[20]阐述了与大蒜相关的另一个活性成分S-烯丙基半胱氨酸(SAC)在生物组织内通过CSE 和CBS的作用产生H2S,从而发挥心脏保护作用。并提出S-烯丙基半胱氨酸可以作为H2S的供体药物用于心脏保护,而大蒜可以直接作为S-烯丙基半胱氨酸的来源而形成内源性H2S,有助于对心脏耐药心肌缺血疾病的治疗。2010年该课题组又发表文章研究S-丙炔基半胱氨酸作为H2S供体在脑组织作用机制研究及半胱氨酸类似物在急性心肌缺血中通过产生H2S发挥活性作用[21-22]。研究中使用的半胱氨酸类似物并不是大蒜的主要成分,S-烯丙基半胱氨酸是陈蒜的主要含硫化合物。

3 体内H2S检测方法研究进展

由于测试方法的不同,组织中H2S的准确生理浓度还不是很清楚,血液中结合与游离态的H2S的范围很广[23],在哺乳动物血浆中浓度为30~100 μmol/L[15,24],在脑组织CBE将半胱氨酸和高半胱氨酸转化为硫化氢,浓度为50~160 μmol/L[23-24]。

目前生物样品中常用H2S检测方法主要有3种:(1)光谱方法为使用最多的一种方法。采用亚甲蓝分析原理:通过醋酸锌吸收H2S,生成稳定的硫化锌,在酸性条件下与N,N-二甲基对苯二胺及FeCl3反应生成亚甲蓝,在610 nm处测定吸光度。样品测定时除衍生化外,测定前还需除去蛋白再行光度法测定[20]。(2)色谱分析方法。离子色谱法可以测定HS-的检测限为30 ppb[25];采用亚甲蓝衍生化后再用HPLC测定,检测灵敏度较光谱法高,并能与干扰物质有效分离[26];利用H2S与对苯二胺和铁(Ⅲ)衍生后生成有荧光的硫堇,采用HPLC荧光检测器进行检测,灵敏度和专属性显著提高,可用于红细胞中H2S的检测[27];此外,还有以邻苯二甲醛和伯胺衍生化,荧光检测含巯基的化合物[28-29]。Kage等[30]通过烷基化萃取技术测定血液中与血清白蛋白结合的硫,检测限可达0.01 mg/g。(3)Krause课题组采用极谱法原位测定样品中H2S[31]。

4 H2S供体药物的研发进展

2007年之后,敏锐药学研究者立刻将注意力转向H2S供体药物的研究上。因含硫化合物通过释放H2S而产生抗细胞凋亡、抗炎和抗氧化作用(anti-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory,antioxidant)等作用与以往研究的结果相吻合。已有研究设计各种硫化物供体药物并研究其在心血管疾病的治疗作用,特别是心肌缺血疾病。源于大蒜的H2S有机硫供体如DADS、DATS、SAC及类似物SPC、SPRC,还有基于H2S研制治疗心血管疾病的药物[32-33],此外S-diclofenac[34-35]、GYY4137[36]、非甾体抗炎药NSAIDs[37-41]、西地那非(sildenafil)[42]也有潜能。

参考文献:

[1] Tyrrell H. Ischemic heart disease and wine or garlic[J]. Lancet,1979, 1(8129):1294.

[2] Kuettner EB, Hilgenfeld R, Purification WM. Characterization and crystallization of alliinase from garlic[J]. Arch Biochem Biophy, 2002, 402(2):192-200.

[3] Josling P. Allicin&Vitamin C-Power, performance, proof[M]. America:HRC Publications, 2010:12-14.

[4] Rose P, Whiteman M, Moore P K, et al. Bioactive S-alk(en)yl cysteine sulfoxides metabolites in the genus allium:the chemistry of potential therapeutic agents[J]. Nat Prod Rep, 2005, 22(3):351-368.

[5] Brady JF, Ishizaki H, Fukuto JM, et al. Inhibition of cytochrome P-450 2E1 by diallyl sulfide and its metabolites[J]. Chem Res Toxicol, 1992, 4(6):642-647.

[6] Nickson RM, Mitchell SC. Fate of dipropyl sulphide and dipropyl sulphoxide in rat[J]. Xenobiotica, 1994, 24(2):157-168.

[7] Jin L, Thomas AB. Metabolism of the chemoprotective agent diallyl sulfide to glutathione conjugates in rats[J]. Chem Res Toxicol, 1997, 10(3):318-327.

[8] Germain E, Auger J, Ginies C, et al. In vivo metabolism of diallyl disulphide in rat:identification of two new metabolites[J]. Xenobiotica, 2002, 32(12):1127-1138.

[9] Arthur JL, Pinto J. Aminotransferase L-amino acid oxidase and β-lyase reactions involving lcysteine S-conjugates found in allium extracts[J]. Biochem Pharmacol, 2005, 69(2):209-220.

[10] Lawson LD, Wang ZJ. Allicin and allicin-derived garlic compounds increase breath acetone through allyl methyl sulfide:use in measuring allicin bioavailability[J]. J Agricult Food Chem, 2005, 53(6):1974-1983.

[11] Lachmann G, Loren ZD, Radeck W, et al. The pharmacokinetics of the S35 labeled labeled garlic constituents alliin, allicin and vinyldithiine[J]. Arzneimittel Forsch, 1994, 44(6):734-743.

[12] Kabil O, Banerjee R. Redox biochemistry of hydrogen sulfide[J]. Biol Chem, 2010, 285(29):21903-21907.

[13] Shibuya N, Mikami Y, Kimura Y, et al. Vascular endothelium expresses 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase and produces hydrogen sulfide[J]. J Biochem, 2009, 146(5):623-626.

[14] Szabo C. Hydrogen sulphide and its therapeutic potential[J]. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2007, 6(11):917-935.

[15] Biteau B,Labarre J,Toledano MB.ATP-dependent reduction of cysteine-sulphinic acid by S-cerevisiae sulphiredoxin[J]. Nature, 2003, 425(6961):980-984.

[16] Giles GI, Tasker KM, Jacob C. Hypothesis:the role of reactive sulfur species in oxidative stress[J]. Free Rad Biol Med, 2001, 31(10):1279-1283.

[17] Munday R, Munday J S, Munday C M. Comparative effects of mono-, di-, tri-, and tetrasulfides derived from plants of the allium family:redox cycling in vitro and hemolytic activity and phase 2 enzyme induction in vivo[J]. Free Rad Biol Med, 2003, 34(9):1200-1211.

[18] Munchberg U, Anwar A, Mecklenburg S, et al. Polysulfides as biologically active ingredients of garlic[J]. Organic Biomol Chem, 2007, 5(10):1505-1518.

[19] Benavides GA, Squadrito GL, Mills RW, et al. Hydrogen sulfide mediates the vasoactivity of garlic[J]. PNAS, 2007, 104(46):17977-17982.

[20] Chuah SC, Moore PK, Zhu YZ. S-allylcysteine mediates cardioprotection in an acute myocardial infarction rat model via a hydrogen sulfide-mediated pathway[J]. Am J Physiol Heart Circulat Physiol, 2007, 293(5):H2693-H2701.

[21] Gong QH, Wang Q, Pan LL, et al. S-propargyl-cysteine, a novel Hydrogen sulfide-modulated agent, attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced spatial learning and memory impairment:involvement of TNF signaling and NF-κB pathway in rats[J]. Brain Behav Immuni, 2011, 25(1):110-119.

[22] Wang Q, Zhu YZ. Protective effects of cysteine analogues on acute myocardial ischemia:novel modulators of endogenous H2S production[J]. Antioxidant Redox Signaling, 2010, 12(10):1155-1165.

[23] Olson R. Is Hydrogen sulfide a circulating “gasotransmitter” in vertebrate blood?[J]. BBA, 2009, 1787(7):856-863.

[24] Fiorucci S, Distrutti E, Cirino G, et al. The emerging roles of hydrogen sulfide in the gastrointestinal tract and liver[J]. Gastroenterology, 2006, 131(1):259-271.

[25] Goodwin LR, Francom D, Dieken FP, et al. Determination of sulfide in brain tissue by gas dialysis/ion chromatography:postmortem studies and two case reports[J]. J Anal Toxicol, 1989, 13(2):105-109.

[26] Haddad PR, Heckenberg AL. Trace determination of sulfide by reversed-phase ion-interaction chromatography using pre-column derivatization[J]. J Chromatography, 1988, 447(2):415-420.

[27] Ogasawara Y, Ishii K, Togawa T, et al. Determination of trace amounts of sulphide in human red blood cells by high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorimetric detection after derivatization with p-phenylenediamine and Iron(III)[J]. Analyst, 1991, 116(12):1359-1363.

[28] Nakamura H,Tamura Z.Fluorometric determination of thiols by liquid chromatography with postcolumn derivatization[J]. Anal Chem, 1981, 53(14):2190-2193.

[29] Mopper K,Delmas D.Trace determination of biological thiols by liquid chromatography and precolumn fluorometric labeling with o-phthaladehyde[J]. Anal Chem, 1984, 56(13):2557-2560.

[30] Kage S, Nagata T, Kimura K, et al. Extractive alkylation and gas chromatographic analysis of sulfide[J]. J Forensic Sci, 1988, 33(1):217-222.

[31] Doeller J E, Isbell T S, Benavides G, et al. Polarographic measurement of Hydrogen sulfide production and consumption by mammalian tissues[J]. Anal Biochem, 2005, 341(1):40-51.

[32] Lei YP, Liu CT, Sheen LY, et al. Diallyl disulfide and diallyl trisulfide protect endothelial nitric oxide synthase against damage by oxidized low-density lipoprotein[J]. Mol Nutri Food Res, 2010, 54(Suppl 1):S42-S52.

[33] Benjamin L, Predmore D,Bennett G,et al. The stable hydrogen sulfide donor,diallyl trisulfide,protects against acute myocardial infarction in mice[J]. Coll Cardiol, 2010, 55(Suppl.10A):A116.

[34] Sidhapuriwala J, Li L, Sparatore A, et al. Effect of S-diclofenac, a novel Hydrogen sulfide releasing derivative, on carrageenan-induced hindpaw oedema formation in the rat[J]. Eur J Pharmacol, 2007, 569(1/2):149-154.

[35] Baskar R, Sparatore A, Del-Soldato P, et al. Effect of S-diclofenac, a novel hydrogen sulfide releasing derivative inhibit rat vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation[J]. Eur J Pharmacol, 2008, 594(1):1-8.

[36] Li L, Whiteman M, Guan YY, et al. Characterization of a novel, water-soluble hydrogen sulfide-releasing molecule (GYY4137):new insights into the biology of hydrogen sulfide[J]. Circulation, 2008, 117(18):2351-2360.

[37] Fiorucci SS, Distrutti EN. Coxibs, CINOD and H2S-releasing NSAIDs:what lies beyond the horizon[J]. Digest Liver Dis, 2007, 39(12):1043-1051.

[38] Sparatore, A, Perrino, et al. Pharmacological profile of a novel H2S-releasing aspirin[J]. Free Rad Biol Med, 2009, 46(5):586-592.

[39] Wallace JL, Caliendo G, Santagada V, et al. Markedly reduced toxicity of a hydrogen sulphide-releasing derivative of naproxen (ATB-346)[J]. Brit J Pharmacol, 2010, 159(6):1236-1246.

[40] Li S, Sang S,Pan MH, et al. Anti-inflammatory property of the urinary metabolites of nobiletin in mouse[J].Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 2007, 17(18):5177-5181.

[41] Giustarini D, Del SP, Sparatore A, et al. Modulation of thiol homeostasis induced by H2S-releasing aspirin[J]. Free Radical Biol Med, 2010, 48(9):1263-1272.

[42] Shukla N, Rossoni G, Hotston M, et al. Effect of hydrogen sulphide-donating sildenafil (ACS6) on erectile function and oxidative stress in rabbit isolated corpus cavernosum and in hypertensive rats[J]. BJU Int, 2009, 103(11):1522-1529.