Bloodstream Infection with Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae and Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter Baumannii: a Case Report

Hong-min Zhang, Da-wei Liu, Xiao-ting Wang, Yun Long, and Huan Chen

Department of Critical Care Medicine, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China

IN the presence of septic shock, every hour in delaying the administration of effective antibiotics is associated with a measurable increase in mortality. This is especially true for neutropenic patients with septic shock.1As there is a higher incidence of involving multi-drug resistant pathogens for neutropenic patients, the decision on antibiotics regime remains a challenge for physicians.2Immunosuppression and previous antibacterial use are factors that promote the spread of multi-drug resistant pathogens, and the possibility of co-existing multi-drug resistant pathogens should be suspected when treating patients with these risk factors who developed refractory shock. Here we present a case with neutropenic fever and refractory shock whose blood culture yielded multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and carbapenem- resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 42-year-old male was diagnosed with gout in 2003, usually took allopurinol and colchicines to ease the pain. The arthralgia exacerbated recently and could not be alleviated by those two medications. A friend of him suggested methotrexate might have a better effect for his illness, upon which he began taking the medicine 4 pills a day without consulting a doctor. He did not stop the medicine until 5 days later when he found herpes around his mouth as well as nasal bleeding and a body temperature of 38°C. After administration of ceftazidime for 5 days at a local hospital and no sign of improvement, laboratory test showed that his leucocyte count was 0.9×109/L, hemoglobin was 85 g/L, and platelet count was 115×109/L. He was treated with calcium folinate, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and blood transfusion, and antibiotics was changed to meropenem. Two days later, his leucocyte count dropped to 0.47×109/L and platelet count to 17×109/L. He developed a persistent high fever above 39°C, even when he was treated for another 2 days with meropenem, vancomycin, and fluconazole. Then he was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit of Peking Union Medical College Hospital.

The patient's medical history was otherwise not notable except for “slightly high serum creatinine” not treated. He was taking no other medications and had no known drug allergies. He was a non-smoker, had never worked outdoors, and had not traveled for the latest 12 months.

On physical examination, the patient was acutely ill-looking, a bit agitated and breathless. Purpura was noticed on his chest skin. The oxygen saturation was 85% while he was breathing ambient air. The heart rate was 122/minute, and blood pressure 80/40 mmHg. Auscultation of his chest revealed no abnormal findings. Heart sounds were normal. The jugular venous pressure was not elevated, and there was no peripheral edema.

Laboratory test showed that his hemoglobin level was 7.2 g/L, the platelet count was 1.1×109/L, and the white blood cell count was 0.31×109/L, with a neutrophil count of 0.07×109/L. The results of liver function tests revealed hyperbilirubinemia, with a conjugated bilirubin level of 110.7 μmol/L. The serum creatinine level was 155 μmol/L and uric acid level was 667 mmol/L. Arterial blood gas analysis showed a pH of 7.32, a partial pressure of oxygen of 49 mmHg, a partial pressure of carbon dioxide of 31 mmHg, and arterial lactate level at 3.8 mmol/L.

A chest radiograph showed no focal abnormality. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed normal biventricular function, normal valves, and an estimated pulmonary artery pressure of 25 mmHg.

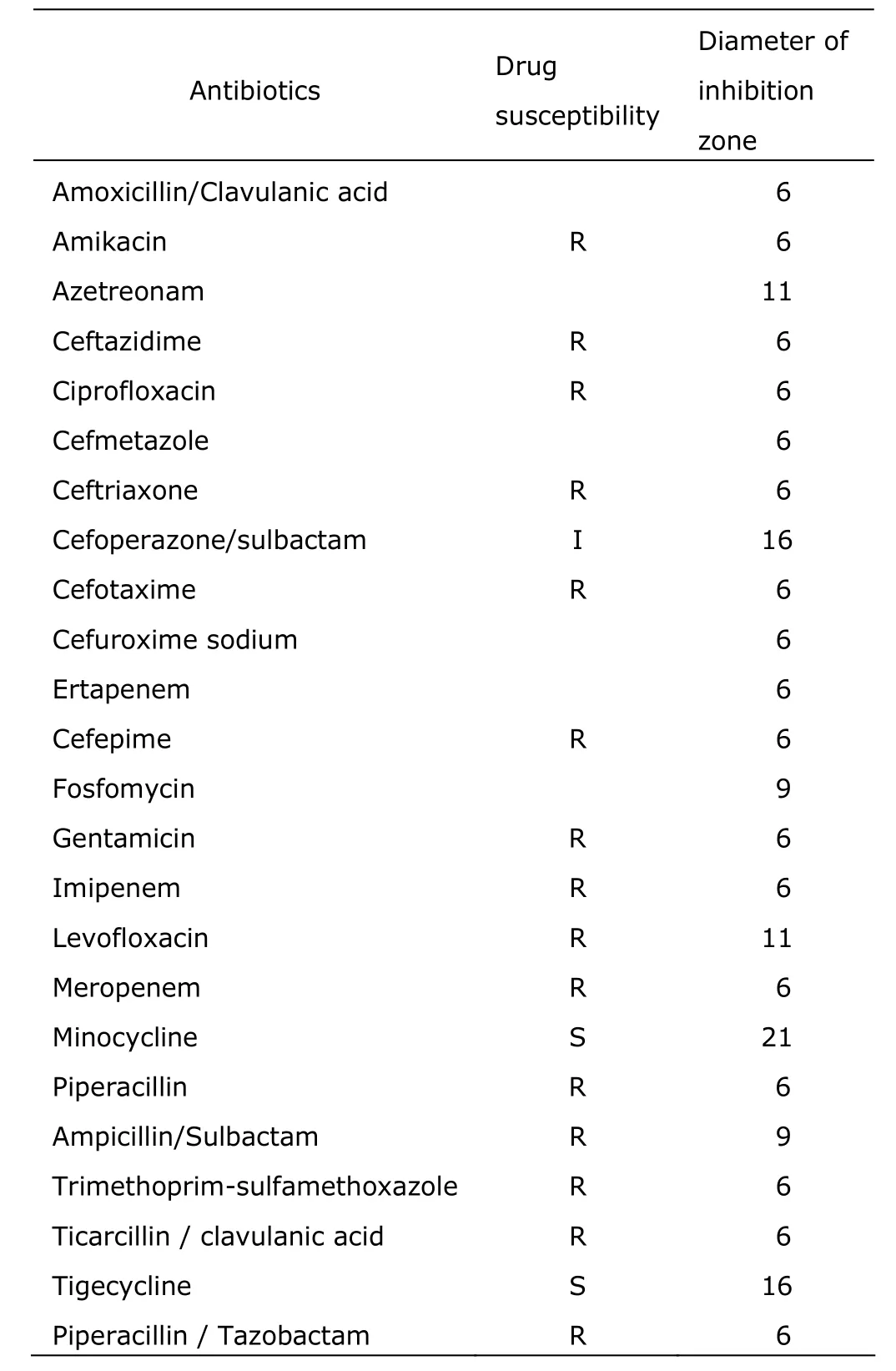

The patient was diagnosed with septic shock and multi-organ dysfunction. Blood was cultured, and medication therapy with meropenem, vancomycin plus amikacin and caspofungin was started. In the meantime he was intubated and on mechanical ventilation. Fluid resuscitation and norepinephrine were given for the shock treatment. But the patient remained febrile, and his absolute neutrophil count dropped to 50 cells/mm3the next day. The serum procalcitonin was 110.7 ng/mL. Blood culture was positive with gram-negative bacilli and coccobacilli. The antibiotics regime was switched from meropenem to cefoperazone/ sulbactam with tigecycline added. Unfortunately his condition continue to deteriorate and died two days later. The blood culture finally yielded Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae (Tables 1, 2).

Table 1. Acinetobacter baumannii in the blood culture of the patient

Table 2. Klebsiella pneumonia in the blood culture of the patient

DISCUSSION

Administering appropriate antibiotics timely is the mainstay of therapy for septic shock patients. Inadequate antimicrobial treatment has been associated with increased mortality in patients with serious infections. And the recently published Surviving Sepsis Campaign guideline underscored that broad-spectrum antimicrobials should be administered within one hour of recognition of septic shock.1However, the decisions about the choice of antibiotics are empirical and not easy, even for the most experienced expert of infectious disease.2For the patient in this case, we are fully aware that no matter what kind of antibiotics we prescribed for him upon admission into the Intensive Care Unit, he may still not be able to survive, unless his bone marrow recovered and his neutrophil count rose to at least 500 cells/mm3. His blood culture involved two multidrug- resistant gram-negative bacteria, which is worth discussing.

In patients with severe neutropenia, especially with an absolute neutrophil count <100 cells/mm3, the risk of systemic bacterial and fungal infections increases at a near-exponential rate.3The respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts and the skin are the major reservoirs of potential pathogens in patients with neutropenia. The risk factors for infection with drug-resistant bacteria listed by Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society in their guidelines include antimicrobial therapy in preceding 90 days, current hospitalization for more than 5 days, high frequency of antibiotic resistance in the community or in the specific hospital unit, and immunosuppression.4The case under discussion fulfilled nearly all risk factors of drug-resistant bacterial infection with longer neutropenic duration, absolute neutrophil count of only 50 cells/mm3, and antibiotics treatment with cephalosporin and carbapenem.

Although an investigation in 391 intensive care unit patients showed that the co-colonizaiton with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter baumannii accounts for 7.6% among the patients,5it is not common to see both organisms cultured at the same time in a patient's bloodstream.

Gram-negative micro-organisms are highly efficient at up-regulating or acquiring genes related to mechanisms of antibiotic resistance, especially in the presence of antibiotic selection pressure. Furthermore, they often resort to multiple mechanisms against the same antibiotic or a single mechanism to affect multiple antibiotics.6If the microbes were sensitive to only one of the administered antibiotics, the possibility of treatment failure was higher than that when the microbes were sensitive to both aminoglycoside and β-lactam antibiotics.

Previous data showed that more than 27% of the bloodstream isolates of Klebsiella pneumonia were resistant to third-generation cephalosporins and 10% were resistant to carbapenems.7Carbapenemase-producing enterobac- teriaceae has caught attention as a major challenge for immune-compromised or severely ill patients. The β-lactamase responsible for this phenotype, also known as Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase, leads to reduced susceptibility to all cephalosporins, monobactams and the carbapenems. Previous antibiotic exposure is a risk factor for carbapenem- resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteraemia.8The β-lactamase is encoded on mobile genetic elements, mostly plasmids and transposons, hence capable of spreading among gram-negative genera. To make the situation more difficult, it often coexists with other resistance genes, leaving the physician with fewer therapeutic options.

Acinetobacter is a gram-negative coccobacillus, which has emerged as an important infectious agent worldwide during the past three decades. That micro-organism could accumulate diverse mechanisms of resistance including β-lactamases, alterations in cell-wall channels, and efflux pumps. Some strains of acinetobacter are resistant to all commercially available antibiotics.9For patients with multidrug-resistant acinetobacters, the most active agents in vitro are the polymixins. Tigecycline is another drug having the active effect against some multidrug-resistant strains of Acinetobacter baumannii, however, certain strains resistant to tigecycline have been reported.10

In conclusion, for a high risk neutropenic patient who was treated with cephalosporins and carbapenems before admission, infections with two multidrug-resistant gram- negative bacteria such as Acinetobacter baumannii plus Klebsiella pneumoniae should be suspected. Clinicians should take this into consideration when deciding the treatment protocol.

1. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med 2013; 41:580-637.

2. Horowitz HW. Fever of unknown origin or fever of too many origins? N Engl J Med 2013; 368:197-9.

3. Safdar A, Armstrong D. Infections in patients with hematologic neoplasms and hematopoietic stem cell trans- plantation: neutropenia, humoral, and splenic defects. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53:798-806.

4. American Thoracic Society, Infectious Disease Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare- associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 171:388-416.

5. Mammina C, Bonura C, Vivoli AR, et al. Co-colonization with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter baumannii in intensive care unit patients. Scand J Infect Dis 2013; 45:629-34.

6. Peleg AY, Hooper DC. Hospital-acquired infections due to gram-negative bacteria. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 1804-13.

7. Souli M, Galani I, Giamarellou H. Emergence of extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli in Europe. Euro Surveill 2008; 13:pii:19045.

8. Hussein K, Raz-Pasteur A, Finkelstein R, et al. Impact of carbapenem resistance on the outcome of patients' hospital-acquired bacteraemia caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Hosp Infect 2013; 83:307-13.

9. Munoz-Price LS, Weinstein RA. Acinetobacter infection. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:1271-81.

10. Rice LB. Challenges in identifying new antimicrobial agents effective for treating infections with Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43 Suppl 2:S100-5.

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2014年1期

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2014年1期

- Chinese Medical Sciences Journal的其它文章

- Reversible Posterior Leukoencephalopathy Syndrome in Children with Nephrotic Syndrome: a Case Report

- Factors Associated with Coronary Artery Disease in Young Population (Age≤40): Analysis with 217 Cases

- Comparison of the Outcomes of Monopolar and Bipolar Radiofrequency Ablation in Surgical Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation

- Laryngo-tracheobronchial Amyloidosis: a Case Report and Review of Literature

- Palliative Local Radiotherapy in the Treatment of Tumor-stage Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma/ Mycosis Fungoides

- Isolated Pancreatic Tuberculosis in Non-immunocompromised Patient Treated by Whipple’s Procedure: a Case Report