Comparison of the Outcomes of Monopolar and Bipolar Radiofrequency Ablation in Surgical Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation

Wei-zhao Huang, Ying-meng Wu, Hong-yu Ye, and Hai-ming Jiang

Cardiothoracic Surgery Department, Zhongshan People’s Hospital (Zhongshan Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University), Zhongshan 528403, China

SALINE-IRRIGATED radiofrequency (RF) ablation- modified Maze III surgery is widely used to treat organic heart disease complicated by atrial fibrillation (AF). In China, most surgeries featuring RF ablation continue to employ the monopolar approach, but even continuous endocardial monopolar RF ablation may not successfully yield a uniform transmural effect. In recent years, bipolar ablation systems have been used to treat entire clamped layers of heart tissue, improving the transmural effect. In the present study, we retrospectively analyzed the outcomes of patients receiving monopolar or bipolar RF ablation to compare the efficacies of the two approaches.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient selection

From January 2007 to March 2011, 81 patients with AF were treated with open cardiac surgery in Zhongshan People's Hospital, including 33 males and 48 females, aged 18-72 years (mean age: 48.2 ± 24.9 years). All the patients had been diagnosed with rheumatic valvular heart disease and all exhibited AF as measured by 12-lead electrocardiography. Preoperative cardiac function was New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II in 28 cases, class III in 44, and class IV in 9. The mean duration of AF was 23.2±14.6 months (range, 8-42 months). The preoperative left atrial diameter as measured by echocardiography was 57.7±16.3 mm (range, 39-68 mm), and the left ventricular end-diastolic diameter was 45.2±14.1 mm (range, 39-61 mm).

Surgical procedure

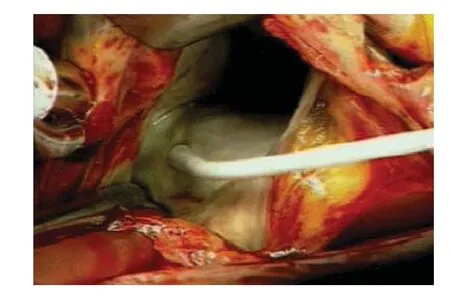

Median sternotomy and heparinization were performed after general anesthesia, followed by conventional establishment of a cardiopulmonary bypass. All right pulmonary veins (RPVs) from the inferior to the superior were bluntly dissected under circulation, and all left pulmonary veins (LPVs) were similarly dissected after induction of circulatory arrest. The Marshall ligament was cut and a Medtronic cardioablation RF system was connected to either an ablation pen or an ablation clamp (as appropriate). The LPVs, RPVs, and the left atrial appendage (Figs. 1 and 2) were subjected to ablation. The principal ablation line commenced at the connection of the right superior pulmonary vein to the left superior pulmonary vein, and proceeded as follows: from the right inferior pulmonary veins to the left inferior pulmonary veins; from the lower end of the incision of the interatrial groove to the mitral annulus; from the left atrial appendage to the left superior pulmonary vein; from the incision in the anterior wall of the right atrium to the postcava; the coronary sinus; and the tricuspid ring (Fig. 3). Valve replacement, plasty, and neoplasty proceeded after completion of ablation. A total of 42 patients underwent mitral valve replacement, 11 mitral valvuloplasty, 9 aortic valve replacement, and 19 mitral and aortic valve replacement; 28 received tricuspid valvuloplasty; and 11 received left atrial thrombus clearance.

Postoperative management

A temporary pacing wire was routinely placed in the ventricular epicardial surface. Intravenous administration of amiodarone commenced after heart resuscitation, changed to oral amiodarone at 200-400 mg/day on the first day after operation and taken for 6 months. Amiodarone or direct current cardioversion was used to treat patients exhibiting postoperative AF. Warfarin was routinely prescribed after mechanical valve replacement; the international normalized ratio was maintained within 2.0-2.5.

Figure 1. The monopolar approach of radiofrequency ablation treatment.

Figure 2. Performance of bipolar ablation in the left atrial appendage.

Figure 3. Radiofrequency ablation line.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 15.0 software was used for all the statistical analysis. Data are expressed as means±SD, raw counts, frequencies, or percentages. The significance of inter-group differences was analyzed using the t-test and Pearson's χ2test. Long-term follow-up data were compared using the Kaplan-Meier method, log-rank text was used to explore survival distributions. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Clinical data

Detailed clinical data of the patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Clinical data of patients in the monopolar and bipolar radiofrequency ablation groups

Table 2. Severe perioperative complications and procedural times in the monopolar and bipolar ablation groups

Outcomes of operation

All the surgeries were successfully performed. The cardio- pulmonary bypass time was 113.2 ± 27.7 minutes, the aortic cross-clamping duration 85.2 ± 24.9 minutes, and the RF ablation time 21.6 ± 8.0 minutes. Three patients exhibited ventricular fibrillation upon heart resuscitation, but defibrillation using electrical shocks restored sinus rhythm. All the other patients experienced normal resuscitation with development of sinus rhythm. No instance of high-degree atrioventricular block was encountered. Three patients required re-operation to ensure hemostasis. Three patients died postoperatively from extremely low cardiac output accompanied by multiple organ failure. All the other patients recovered after the operation. The total procedural time using bipolar RF ablation was significantly shorter than that using monopolar ablation (19.7±4.6 minutes vs. 28.1±8.5 minutes, P < 0.001, Table 2).

Cardiac rhythm on postoperative day 1

Of all the patients examined on the first postoperative day, 68 (84.0%) exhibited sinus rhythm, 10 (12.3%) junctional or pacing rhythm, and 3 (3.7%) AF. One week after operation, 66 patients (81.5%) showed sinus rhythm, 6 (7.4%) junctional rhythm, 3 (3.7%) atrial flutter rhythm, and 6 (7.4%) AF. A total of 78 patients received postoperative follow-up for 15.1±12.6 months (range, 1-49 months). At the last follow-up visit, sinus rhythm was evident in 57 patients (73.1%), atrial flutter rhythm in 2 (2.6%), and AF in 19 (24.3%). Cardiac function status was NYHA class I in 43 patients and class II in 35. No patient died or experienced stroke or limb embolism.

Re-establishment of sinus rhythm

Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed no significant difference between the 2 groups in 36-month sinus rhythm restoration rate (68.3% in bipolar vs. 50.2% in monopolar, P=0.199, Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Sinus rhythm restoration rates in the monopolar and bipolar ablation groups.

DISCUSSION

The Maze procedure is widely adopted in treatment of AF.1In recent years, Cox's Maze procedure has gradually replaced traditional “cut and sew” operations with small wound ablations using various forms of energy, of which RF has received the most attention. Both monopolar and bipolar RF ablation are used in China today. In the present study, we retrospectively compared the efficacy of monopolar and bipolar RF ablation used to control AF during heart valve surgery.

RF ablation uses molecular vibration to generate heat. The temperature rises to 50°-60° in the vicinity of the atrial wall, resulting in regional myocardial necrosis. For ablation to be effective, it must be transmural in nature and linearly continuous.2,3However, monopolar RF ablation cannot guarantee a complete transmural effect; the extent of transmural ablation varies with the level of operator experience and is associated with the risk of perforation. Bipolar RF ablation relies on changes in tissue conductivity to indicate the extent of transmural ablation. A competent operator can ensure complete transmural ablation by measuring the decline in tissue conductivity between ablation clamps and controlling the ablation time. Therefore, bipolar ablation is, in theory, more effective and safer than monopolar ablation.

To avoid the shortcomings of monopolar ablation, combination of endocardial and epicardial ablation4and that of monopolar and bipolar ablation have been developed.5In the present study, the proportions of patients who exhibited sinus rhythms soon after operation and later were both lower in the monopolar group than those in the bipolar group. However, no significant inter-group difference in the cumulative sinus rhythm restoration rate was observed. Geidel et al6found that 66.7% and 50% (respectively) of patients treated using monopolar or bipolar ablation exhibited sinus rhythms postoperatively. Onan et al7reported that 83.3% and 68.8% of patients treated with monopolar and bipolar ablation respectively exhibited restoration of sinus rhythm upon long-term follow-up. In both of the cited studies, the patients treated with monopolar ablation showed higher rates of sinus rhythm, but the differences were not significant. Therefore, both studies concluded that monopolar and bipolar ablation had similar effects. Thus, although effective monopolar ablation may require a high level of skill, appropriate monopolar treatment may be as effective as bipolar ablation. It must be noted that, apart from ablation, case selection, design of the ablation line, and perioperative anti-arrhythmic therapy all affect the effect of AF control. Thus, intraoperative RF ablation is but a component of treatment, not a stand-alone approach. A recent study showed the overall freedom from AF at late follow-up did not differ for the two approaches (monopolar vs. bipolar) and the presence of early atrial tachyarrhythmia and age were predictors of AF recurrence.8

No significant inter-group difference in the postoperative incidence of severe complications (mortality and bleeding) was observed in this study, suggesting that the two ablation methods were comparable in terms of safety, in agreement with the findings of Onan et al7. The monopolar approach required a significantly longer ablation time compared with the bipolar approach (P<0.001). One possible reason is that monopolar ablation was adopted earlier in our hospital and an initial lack of experience with the RF ablation Maze procedure may have resulted in longer procedural times. Another reason is associated with the differences between the two ablation systems. Bipolar ablation is easier to control; a transmural ablation may be completed in only 3-5 seconds using the transmural monitoring function. Thus, in the present study, the mean ablation time in the bipolar group was 19.7±4.6 minutes, consistent with previous studies.9-11When monopolar ablation is used, in contrast, more careful observation is often required to ensure that ablation is indeed transmural and to avoid atrial tissue-penetrating injury. Sometimes minimally invasive suturing or repair is necessary to treat suspected or apparent left atrial penetrating wounds. This factor obviously increases the duration of the ablation procedure.

In conclusion, both monopolar and bipolar RF ablation are safe and effective when used to treat chronic AF in patients during open cardiac valve surgery, but bipolar RF ablation is a more convenient method than monopolar approach.

1. Gillinov AM, Wolf RK. Surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2005; 48:169-77.

2. Cox JL. The role of surgical intervention in the management of atrial fibrillation. Tex Heart Inst J 2004; 31:257-65.

3. Haïssaguerre M, Jaïs P, Shah DC, et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating from the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med 1998; 339:659-66.

4. Wang JG, Meng X, Li H, et al. Combined endocardial and epicardial radiofrequency modified Maze procedure in the treatment of atrial fibrillation. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi 2007; 45:415-8.

5. Lim SL, Chua YL. Surgery for atrial fibrillation. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2004; 33:432-6.

6. Geidel S, Ostermeyer J, Lass M, et al. Three years experience with monopolar and bipolar radiofrequency ablation surgery in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2005; 27:243-9.

7. Onan B, Onan IS, Caynak B, et al. Comparison of the results of irrigated monopolar and bipolar radiofrequency ablation in the surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg 2011; 11:39-47.

8. Lazopoulos G, Mihas C, Manns-Kantartzis M, et al. Radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation during concomitant cardiac surgery: mid-term results. Herz. 2013 Mar 30 [cited 2013 Dec 13]. Available from: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00059-01 3-3787-1

9. Voeller RK, Zierer A, Lall SC, et al. Efficacy of a novel bipolar radiofrequency ablation device on the beating heart for atrial fibrillation ablation; a long-term porcine study.J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010; 140: 203-8.

10. Canale LS, Colafranceschi AS, Monteiro AJ, et al. Use of bipolar radiofrequency for the treatment of atrial fibrillation during cardiac surgery.Arq Bras Cardiol 2011; 96: 456-64.

11. Gillinov AM. Advances in surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. Stroke 2007; 38:618-23.

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2014年1期

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2014年1期

- Chinese Medical Sciences Journal的其它文章

- Sorafenib in Liver Function Impaired Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma

- Isolated Pancreatic Tuberculosis in Non-immunocompromised Patient Treated by Whipple’s Procedure: a Case Report

- Reversible Posterior Leukoencephalopathy Syndrome in Children with Nephrotic Syndrome: a Case Report

- Laryngo-tracheobronchial Amyloidosis: a Case Report and Review of Literature

- Bloodstream Infection with Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae and Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter Baumannii: a Case Report

- Factors Associated with Coronary Artery Disease in Young Population (Age≤40): Analysis with 217 Cases