海水甲壳类寄生性病原血卵涡鞭虫(Hematodinium spp.)研究进展*

李才文 许文军

海水甲壳类寄生性病原血卵涡鞭虫(spp.)研究进展*

李才文1①许文军2

(1. 中国科学院海洋研究所海洋生态与环境科学重点实验室 青岛 266071; 2. 浙江省海洋水产研究所海水增养殖重点实验室 舟山 316100)

血卵涡鞭虫(spp.)是一类危害海水甲壳类的致病性寄生性甲藻, 在世界范围内严重威胁了多种重要经济甲壳类的渔业生产。近年来, 血卵涡鞭虫先后在我国浙江、广东沿海的锯缘青蟹、三疣梭子蟹、脊尾白对虾等重要养殖甲壳类中被报道发现, 并已确定该寄生病原是近年来引起当地养殖青蟹“黄水病”、三疣梭子蟹“牛奶病”和脊尾白对虾大规模死亡的主要病原之一。本文结合作者近年来关于spp.的研究成果, 系统综述了国内外该寄生性病原的研究进展, 包括其系统分类、生活史、传播途径、发生机制等; 并针对目前该寄生性病原研究中存在的关键问题, 结合我国相关研究现状做出了分析和展望, 以期为我国海水甲壳类血卵涡鞭虫流行病的预防与控制提供理论依据和技术支持。

寄生性甲藻; 生活史; 传播途径; 孢子; 水产养殖

血卵涡鞭虫(spp.)是一类危害海水甲壳类的致病性寄生性甲藻(parasitic dinoflagellate), 它具有间核结构、蜂窝状表皮、无甲片甲藻孢子和特征分裂方式等甲藻的典型特征 (Chatton, 1931; Ris, 1974)。自1931年Chatton等首次在法国沿岸绿蟹()报道发现感染以来, 已经在世界范围内20多种螃蟹、1种对虾、1种龙虾和十几种端足类动物中检测到和-like spp.感染(表1)。近二十年来,已经先后在法国、英国、加拿大、澳大利亚和美国等国家近岸海域大范围流行(图1), 并严重威胁到了挪威龙虾()、美国兰蟹()、蛛雪蟹()、白氏雪蟹()等多种重要经济甲壳类的渔业生产(Field, 1992; Meyers1987; Messick, 2000; Stentiford, 2002, 2003, 2005; Sheppard, 2003)。

近年来, 我们先后在浙江舟山、宁波和台州海域的海捕和养殖三疣梭子蟹()、锯缘青蟹()等甲壳类体内检测到感染, 并已初步确定该寄生性病原是近年来引起浙江沿海海水养殖三疣梭子蟹大规模死亡“牛奶病”和青蟹“黄水病”的主要病原之一(许文军等, 2007a, b)。2008年Li等在我国广东汕头低盐养殖的锯缘青蟹中也发现并报道了的发生。最近, 我们在养殖脊尾白对虾 ()中也发现了感染, 并确认其是导致当地脊尾白对虾规模性死亡的主要病原, 这是迄今为止首例在对虾类中确认报道的感染 (Xu, 2010)。的发生, 不仅给我国虾蟹类养殖业造成了直接的经济损失; 而且由于缺乏有效的控制方法, 许多养殖户往往在疾病发生时大量使用抗生素和杀虫剂等, 在危害养殖产品品质的同时, 也造成了周边海水环境的污染。目前国内有关该寄生性甲藻的相关研究集中于实地调查、病原确定、诊断技术等前期研究, 尚缺乏有关该类寄生性甲藻生活史特征及其传播途径等方面的基础研究, 这些基础研究的缺失已经制约了在实际渔业生产中的针对性预防和控制。

图1 Hematodinium spp.在世界范围内的分布

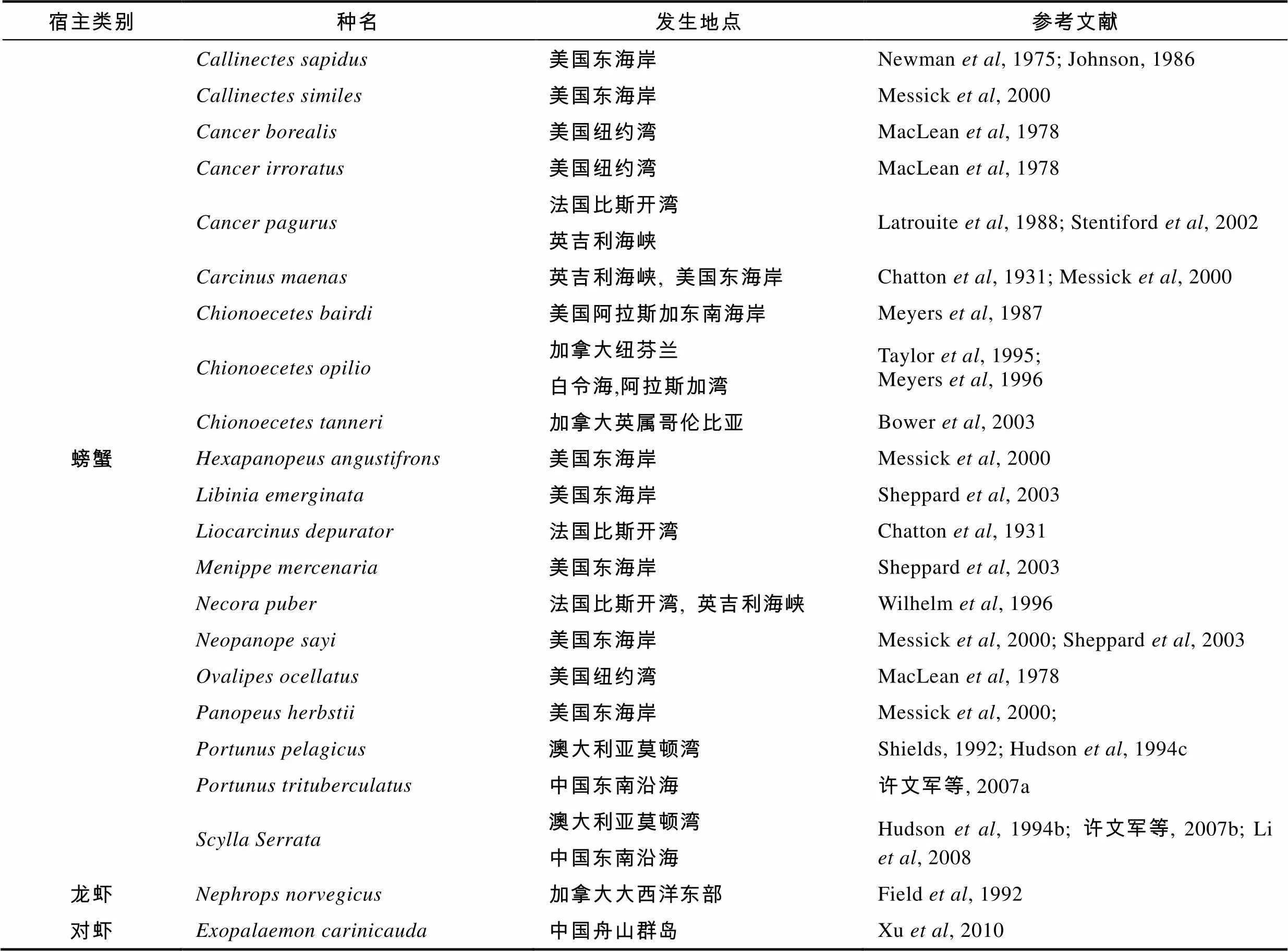

表1spp.的主要海水甲壳类宿主

Tab.1 Major crustacean species infected by Hematodinium spp.

1 系统分类

的系统分类地位并没有最终确定, 文献中报道的和-like spp.组成属暂列在甲藻(Dinophyceae)纲、寄生藻目(Syndiniales)、寄生藻(Syndiniaceae)科下(Integrated Taxonomic Information System; NCBI Taxonomy Data Base; Stentiford, 2005)。目前该属仅有两个正式命名的物种, 典型种和。典型种最早在法国诺曼底和地中海沿岸的两种梭子蟹和中被报道发现(Chatton, 1931); 后来在附近海域的黄道蟹()和英吉利海峡的天鹅绒梭子蟹()中也报道了的流行(Latrouite, 1988; Wilhelm, 1996; Stentiford, 2002, 2003)。另外一种发现于澳大利亚的深海梭子蟹中, 但这种不仅形态和大小上都与有差异 (Hudson, 1994), 而且18S rRNA的分子测序也存在差异(Hudson, 1996)。而在我国发现的sp.及其它和-like spp.都没有正式命名。另外, 在挪威龙虾、蛛雪蟹和白氏雪蟹中发现的被认为是不同的种(Meyers, 1987; Field, 1992)。在早期文献中, 研究者认为在美国兰蟹()中发现的与典型种属于同一种因而一直沿用这一命名; 然而最新研究表明这种与典型种是不同的基因型(Small, 2012)。相信随着分子生物学技术的广泛应用和生活史研究的进一步深入, 我们对于的系统分类将会有更清晰的认识。

2 生活史

的生活史比较复杂, 通常至少包括多核原生质期(multinucleate plasmodial stage)、滋养体(trophont)和孢子(dinospore)三个阶段 (Shields, 1994; Stentiford, 2005)。有关生活史研究的报道较少, 目前只有从挪威龙虾和美国兰蟹中分离出来的种已经有了较为完整的生活史研究(Appleton, 1998; Li, 2011a), 除此之外, 包括典型种在内的其它30多种都没有生活史方面的系统研究, 这也从客观上限制了该类寄生虫在系统分类和传播途径方面的研究。Appleton等(1998)从挪威龙虾中分离出并在实验室内实现了连续培养。结果发现大孢子(macrospore)或小孢子(microspore)先发展成为丝状滋养体(filamentous trophont), 而后进一步形成丝状滋养体集合体(Gorgonlocks trophonts colony)。这些丝状滋养体集合体既能发展成为团块状聚合体(clump colony), 而后形成更多的丝状滋养体; 又会发育成为蛛网状滋养体(arachnoid trophonts), 并发展成为蛛网状孢子体(arachnoid sporonts)。蛛网状孢子体通过孢子生殖产生大量孢子母细胞(sporoblasts), 进一步发展成为大孢子或小孢子。

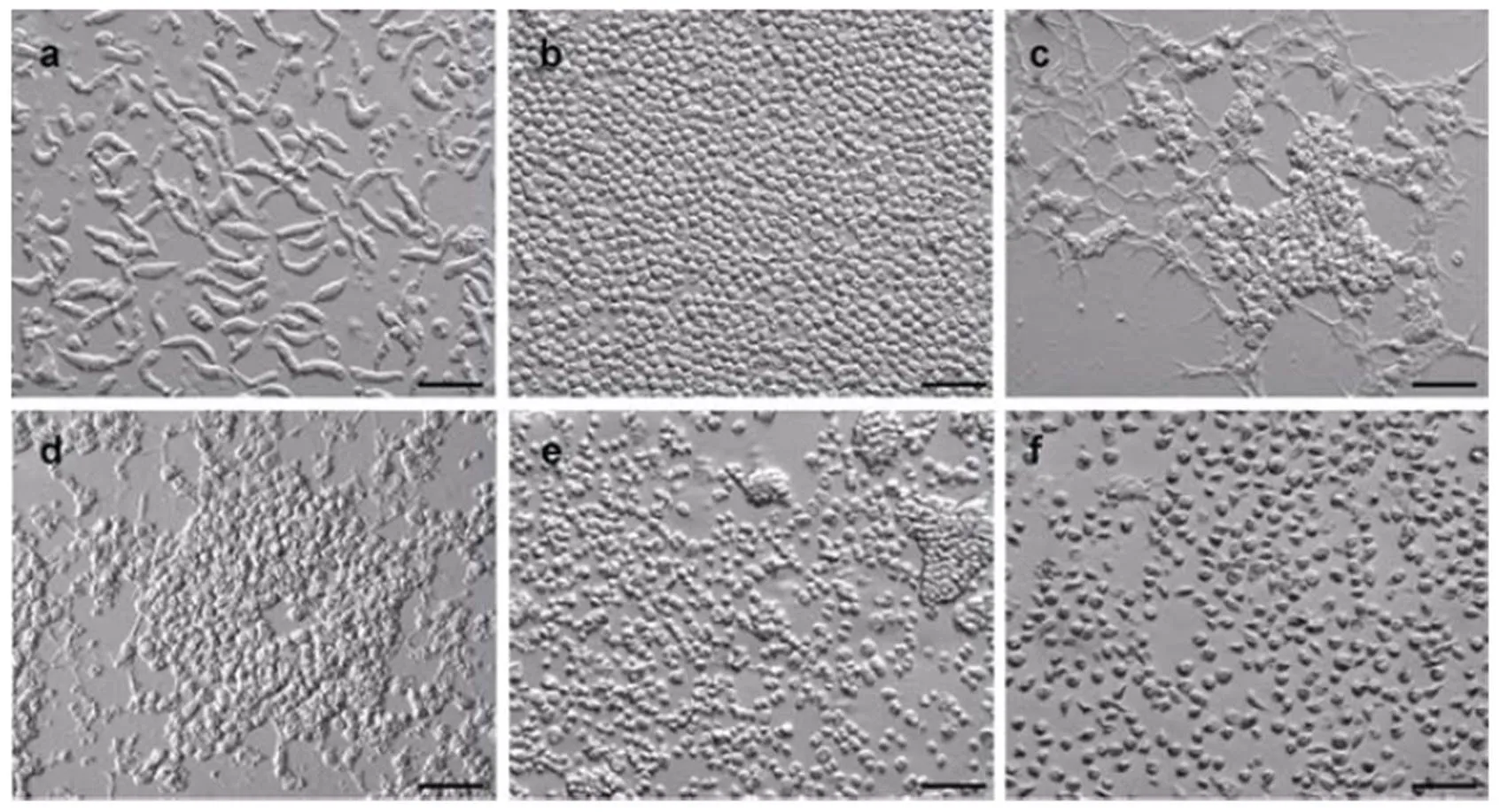

最近, 美国兰蟹中的生活史研究也取得了突破性进展, Li等(2011a)首次实现了ex的体外连续培养, 并阐明了其完整生活史。与挪威龙虾的生活史类似, 兰蟹中的生活史经历了丝状滋养体(图2a)、类变形虫滋养体(amoeboid trophont)(图2b)、蛛网状滋养体(图2c)、蛛网状孢子体(图2d)、孢子母细胞、孢子前细胞(prespore)(图2e)和孢子(图2f)等阶段。然而, 兰蟹中的生活史发展过程与挪威龙虾的生活史又存在明显差异(Appleton, 1998; Li, 2011a)。首先丝状滋养体集合体(Gorgonlocks trophonts colony)并不是由丝状滋养体发展而成, 而是从裂殖体(schizont)中发展出来, 而后形成为丝状滋养体, 并进一步发展成团块状聚合体。裂殖体(schizont)这个发展阶段是首次在生活史中报道发现。裂殖体一般出现在蛛网状孢子体的发展末期, 包埋在孢子母细胞中。网状孢子体是兰蟹中的生活史发展的重要阶段, 它既可以延续在宿主体内的继续增殖, 又承启在宿主体内的持续感染。但是究竟是什么因素调控蛛网状孢子体生成裂殖体或孢子母细胞有待进一步 研究。

3 传播、扩散方式

在虾蟹类宿主中的传播途径目前尚未清晰, 这很大程度上受限于我们对生活史以及关键生活史阶段在传播过程中的作用缺乏了解。同类相食(cannibalism)、性传播(sexual transmission)和水体传播(waterborne transmission)是海水病原微生物的常见传播途径。Meyers等(1996)在少数几个白氏雪蟹的雄性个体输精管液体中发现了, 认为性传播是的可能传播途径之一, 但迄今没有进一步的研究证实这一假设。近年来研究者虽然进行了一些投喂感染实验, 但对于同类相食是否是主要的传播途径尚无一致的结论。Hudson等(1994c)发现澳大利亚深海梭子蟹并不能通过摄食染病蟹组织获得感染。Sheppard等(2003)提到在美国兰蟹中可以通过投喂染病组织在幼蟹()中传播, 但并没有详细实验报道。近来, Walker等(2009)研究报道, 经过一次投喂实验, 63%的实验兰蟹(共11只)在24小时内检测出感染, 并且有些已经呈重度感染。这些结果与文献中报道的在兰蟹宿主体内的增殖过程有很大差异, 因为在兰蟹注射感染实验中, 注射高剂量虫体后7—14天才会发现中度感染的宿主(Shields, 2000)。

图2 美国兰蟹中Hematodinium sp.的典型生活史阶段

a. 丝状滋养体; b. 类变形虫滋养体; c. 蛛网状滋养体; d.蛛网状孢子体; e. 孢子母细胞、孢子前细胞; f. 孢子. 图中比例尺为50μm

鉴于同类相食(cannibalism)这种传播方式的争议性结论, 笔者用幼体和成体兰蟹进行了多次投喂感染实验(Li, 2011b), 结果发现在120只实验兰蟹中, 只发现两只兰蟹感染, 而且这两只兰蟹很可能在实验前已经携带, 只是在实验前的初检中没有被检测出来。在同时进行的注射感染实验中, 直到注射感染后11—21天才发现有明显的感染。这些实验结果与Walker等(2009)有明显差异, 本文认为在实验中使用了具有隐性感染的兰蟹可能是导致不同结论的原因之一。大部分蟹类是很活跃的同类摄食类, 而且成蟹比幼蟹具有更高的捕食率, 因此假如同类相食是传播的首要途径,应该在成蟹中具有更高的发病率, 但这种假设结果与实地的流行病调查结果不符, 因为在幼体宿主中发病率更高(Messick, 1994; Field, 1998; Messick, 2000)。而且如果同类相食是传播的首要途径, 由于蟹类的同类相食在摄食期间是一直发生的, 理论上推测在宿主群体的发病率应该相对稳定, 而不是观察到的季节性发病(Meyers, 1990; Eaton, 1991; Love, 1993; Messick, 1994, 2000; Field, 1998; Sheppard, 2003)。因此, 同类相食在该类病害传播过程中的确切作用, 以及在宿主群体间的主要传播途径还有待于进一步研究。

与典型甲藻类似, 大多数寄生性甲藻也是通过孢子在水体中扩散和个体间传播(Anderson, 1982; Cachon, 1987; Coats, 1999)。Appleton等(1998)在进行ex.连续培养时发现孢子可以直接发展为丝状滋养体, 而丝状滋养体一般出现在感染初期的宿主内; 笔者在进行ex培养时也发现了类似的发生发展模式(Li, 2011a)。有文献报道长期感染的甲壳类宿主在感染晚期会通过腮丝释放大量的孢子到环境水体中(Appleton, 1998; Shields, 2000), 宿主在释放孢子不久后死亡(Love, 1993; Stentiford, 2002)。笔者在研究美国兰蟹中的时, 也多次发现重度感染的兰蟹会释放大量的孢子, 在暂养池内孢子浓度可达106/mL以上 (Li, 2010), 这些孢子在局部范围内的浓度甚至高于某些典型的有害藻华(Hallegraeff, 1993; Smayda, 1997)。Eaton等(1991)报道在白氏雪蟹()时发现的大小两种孢子注射到健康蟹体内后, 都可以引起新的感染。我们最近还发现兰蟹中孢子在适宜盐度条件下(>20)一般可存活5—7天以上, 而滋养体阶段则在24小时内已经死亡或丧失活性(Li, 2011b)。由此我们推断孢子很可能是传播过程的关键阶段; 然而,孢子是真正的传播阶段, 还是一个中间阶段?孢子怎么由环境水体进入新的宿主体内并造成感染?这些都有待进一步的调查研究和实验验证。

4 发病规律

在易感虾蟹类宿主群体的发病具有明显的季节性。长期的流行病学调查显示, 在挪威龙虾中一般在冬春季达到发病高峰(发病率可达70%), 而在夏秋季则降至低点(发病率18%—35%)(Field, 1992, 1998; Stentiford, 2001a; Briggs, 2002)。在白氏雪蟹中,一般在夏季达到发病高峰, 到冬季则降至低点(Meyers, 1990; Eaton, 1991; Love, 1993)。在美国兰蟹中,一般在秋季达到明显的发病高峰, 在冬季则几乎检测不到发病; 而后到第二年春天, 发病率又开始回升 (Messick, 2000; Sheppard, 2003)。在幼体虾蟹中具有较高的发病率, 而幼体需经过多次连续蜕皮后才能成长为成体(Tagatz, 1968), 上述几种虾蟹类都有季节性的蜕皮现象。因此很多研究者认为在这些宿主内的传播发生与宿主蜕皮有紧密联系(Meyers, 1990; Eaton, 1991; Field, 1992; Love, 1993; Stentiford, 2001a; Shields, 2005)。Meyers等(1990)和Love等(1993)研究发现重度染病白氏雪蟹一般在夏季释放孢子, 认为疾病传播也发生在夏季并达到发病高峰。据此, 不少研究者推测孢子有可能在宿主蜕皮期间侵入宿主体内而造成疾病的发生和大规模传播, 但具体机理尚不清楚(Meyers, 1990; Eaton, 1991; Stentiford, 2001a; Shields, 2005, 2007)。

的流行也受温度、盐度等环境因素的影响。Messick(1999)发现当水温高于15°C时, 美国兰蟹的感染较严重, 水温低于15°C则感染较少。另外笔者在进行美国兰蟹体外培养时, 也发现当温度低于15°C时,生长发育比较缓慢, 甚至不能完成生活史(Li, 2011a)。Appleton等(1998)研究发现挪威龙虾生长发育的适宜温度范围为8—15°C。除温度外, 盐度也是影响传播的重要因素之一。在生活在盐度低于18的美国兰蟹中, 几乎没有发现感染(Newman, 1975; Messick, 1992, 2000)。Coffey等(2012)进行了美国兰蟹在不同盐度条件下的感染实验, 发现盐度并不能影响在兰蟹体内的增值, 尽管的孢子在盐度低于15的水体中会迅速失去活性而死亡(未发表数据)。这说明携带感染的兰蟹在低盐条件下会继续发展感染, 但由于释放到水体的孢子会迅速死亡, 可能并不会造成的继续传播。

5 定性、定量检测

有些严重感染的个体可以通过外部症状观察初步确定, 例如感染的宿主其外观会体色暗淡或关节膜处呈白垩色, 重度感染的挪威龙虾()会呈现出甲壳高温加热变性后特有的红橙色(Field, 1992; Stentiford, 2000)。此外,感染会导致宿主肌肉口感改变, 如蛛雪蟹()和白氏雪蟹()感染后肉质变苦, 在当地又称为“苦蟹病” (bitter crab disease, BCD)(Meyers, 1987; Taylor, 1995; Dawe, 2002)。然而, 在美国兰蟹和我国养殖虾蟹类中发现的感染没有明显的体表症状, 需要借助血涂片法和化学染色法进一步确认感染(Messick, 1994; Messick, 2000; 许文军等, 2007a, 2007b, 2010)。

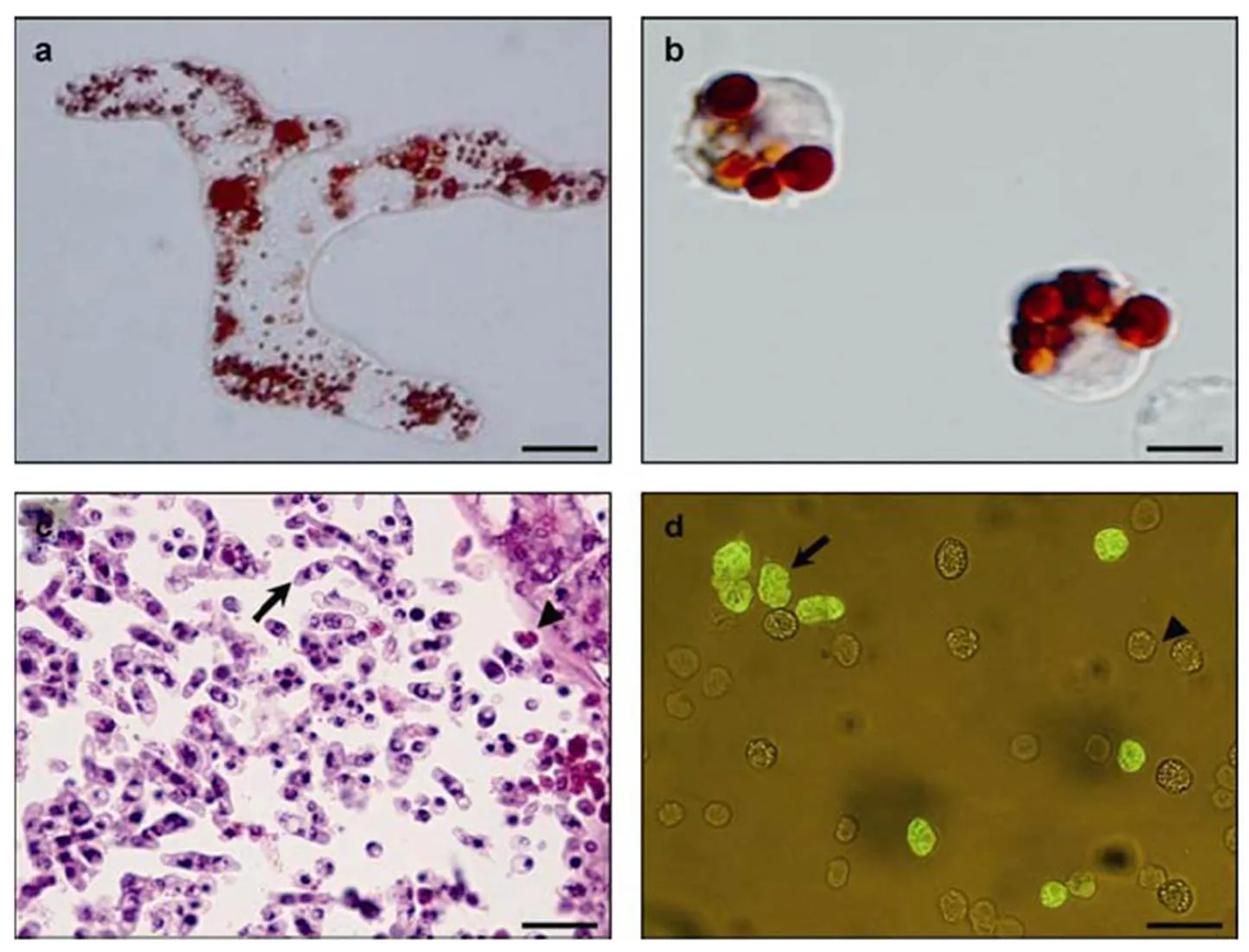

主要寄生于甲壳类宿主的血淋巴和血腔、肝胰腺、心脏、肌肉等组织器官的血腔内。感染晚期的宿主的血细胞数量会显著降低, 代之以大量寄生虫体; 血淋巴由正常时的蓝青色、能瞬间凝集的液体转变为淡黄色或乳白色牛奶状不能凝固的变性液体。在血淋巴液中可观察到典型发育阶段的虫体, 如丝状变形体(filamentous trophonts or plasmodium)、单核或多核滋养体阶段(trophonts)、以及甲藻孢子阶段(dinospores)。利用显微镜观察中性红染色的新鲜血淋巴涂片(wet smears), 可以基本确定是否有该寄生虫的感染; 除孢子阶段外, 血淋巴中常见的丝状变形体和滋养体细胞中的溶酶体(lysosomes)均会被中性红染色, 从而在显微镜下显示特征红色(Stentiford, 2005)(图3a, b)。另外, 也可以通过制作干血涂片, 而后用甲醇或Bouins固定剂固定, 再用Giemsa或苏木精-曙红(hematoxylin-eosin staining, H&E)染色(图3c)来定性检测感染 (Meyers, 1987; Love, 1993; Hudson, 1994c; Messick, 1994; Messick, 2000)。

图3 Hematodinium spp.的常见病理学形态及检测

a. 中性红染色的丝状滋养体; b. 中性红染色的类变形虫滋养体; c. H&E染色的感染肝胰腺组织(长箭头指示丝状滋养体, 短箭头指示宿主组织细胞); d. 间接荧光抗体检测血淋巴中类变形虫滋养体(长箭头指示类变形虫滋养体, 短箭头指示血淋巴细胞). 图中a 和b 比例尺为10μm, c 和d 比例尺为20μm.

组织病理学检测显示患病宿主的肝胰腺、心脏、肌肉、鳃的组织切片中均会观察到大量寄生原虫, 被寄生虫侵袭的组织出现以坏死为主的变质性病变。肝胰腺细胞大部分水肿、变性, 可见轻度细胞排列紊乱, 部分细胞核坏死消失; 肝管上皮细胞间界线模糊、消失, 细胞核固缩或溶解, 乃至整个肝管细胞都坏死, 肝管间的血腔隙及结缔组织间充满大量寄生原虫。染病宿主鳃丝变性、坏死, 鳃上皮细胞水肿变性, 鳃腔扩张, 鳃腔内有大量寄生原虫。心肌纤维浊肿, 呈现与步足肌相同的肌纤维断裂溶解现象, 大部分横纹消失, 心肌纤维弯曲、断裂和局部坏死, 其间寄生有大量寄生原虫。足部肌肉纤维断裂, 横纹消失, 呈均质样变性或坏死; 肌束间空隙扩大并寄生有大量虫体。感染末期的甲壳动物宿主往往由于寄生虫在体内大量增生而造成宿主感染器官的显著组织病理变化, 并最终由于呼吸代谢系统功能紊乱乃至丧失而死亡 (Field, 1995; Taylor, 1996; Stentiford, 2005)。

除上述方法外, 分子生物学技术如PCR、DNA探针、qRT-PCR等在的定性、定量检测方面都得到了广泛应用。例如早期的针对属 (Hudson, 1994a, 1996; Gruebl, 2002; 施慧等, 2008), 以及更为特异的针对ex.种的定性传统PCR方法和DNA探针检测(Small, 2007; Li, 2010)都可以比较灵敏的检测轻度感染; 基于环介导恒温扩增技术(Loop- mediated isothermal amplification, LAMP)的高灵敏度、快速诊断方法也得到了实际应用(施慧等, 2010); 另外, 实时荧光定量PCR(quantative real-time PCR)技术也成功地用于定量检测水体中的孢子(Frischer, 2006; Nagle, 2009; Li, 2010)。基于细胞多克隆抗体的酶联免疫吸附检测(Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, ELISA)和间接荧光抗体检测技术(Indirect fluorescent antibody technique, IFAT)(图3d)等在的检测方面也得到了一定程度的应用(Stentiford, 2001b; Small, 2002; 谢建军等, 2009; 查智辉等, 2011)。

6 我国Hematodinium研究现状及展望

孟庆显和俞开康早在1996年综述国内外海水养殖常见疾病时曾引述了国外的研究(孟庆显等, 1996), 并将译为血卵涡鞭虫。

2004年7—9月, 许文军等在对浙江舟山市三疣梭子蟹养殖基地“牛奶病”病蟹取样调查时发现, 大部分濒死的病蟹有相似的典型症状, 即蟹体消瘦, 肌肉白浊, 蟹盖内充满大量乳白色液体。光镜观察乳白色液体发现大量虫体, 几乎没有血淋巴细胞。高倍显微镜和电镜观察, 可清楚看到该寄生虫带有两根鞭毛, 大小约7—9μm。从不同病蟹的血淋巴液中发现了处于其他发育阶段的虫体, 大多呈卵圆型, 大小约14—16μm。染病梭子蟹的内脏及肌肉组织有显著的组织病理变化, 被侵染的组织出现以坏死为主的变质性病变, 在H&E染色的肝胰腺、心脏、肌肉、腮的组织切片中均发现有大量寄生虫。该寄生虫的大小、形态、内部结构、寄生部位以及宿主组织病理变化, 均与文献中报道描述的类似。采用针对的特异性PCR检测发现, 阳性样品均能扩增出分子量为580bp左右的特异性条带, 并且序列一致 (Hudson, 1994a, 1996), 由此确定该寄生虫为一种sp. (许文军等, 2007a, b)。

进一步研究发现, 所有“牛奶病”病蟹肝胰脏、心脏、足部肌肉以及鳃等部位均充满上述寄生虫, 而作为对照组健康梭子蟹的各器官组织中则未发现, 表明该寄生虫与梭子蟹的牛奶症有密切关系。“牛奶病”病蟹发病中后期, 由于寄生虫的大量寄生, 导致血淋巴数量急剧下降, 使体液表现出浊白色和不能凝聚等症状; 同时病蟹各重要组织器官均发生严重病变, 导致主要生理功能丧失, 如鳃组织病变, 导致呼吸功能受阻, 病蟹往往浮游于水面或池边浅水处, 进而死亡; 心肌纤维病变, 导致血淋巴循环障碍; 肝胰腺病变, 导致新陈代谢紊乱, 病蟹摄食、活动能力减弱, 反应迟钝, 行动缓慢等, 进一步导致病蟹死亡。对病蟹的细菌分离培养结果显示, 多数病蟹的血淋巴以及肝胰腺未分离到细菌; 虽然少数分离到细菌, 但是种类较杂, 且不同病蟹缺少共性; 我们认为细菌是在梭子蟹体质下降, 感染卵涡鞭虫的同时或之后获得的继发感染, 虽然其可能促进病蟹的死亡, 但并非此次梭子蟹“牛奶病”的主要病原。另外, 电镜结果显示, 病蟹的肝胰腺、心肌、血淋巴以及鳃丝等组织均未发现有病毒颗粒, 而血卵涡鞭虫则在所有的组织中大量存在。综合调查研究结果, 我们确定血卵涡鞭虫(sp.)是导致这次养殖梭子蟹“牛奶病”暴发死亡的主要病原。这也是国内首次报道的蟹类sp.感染并在养殖中引起暴发性死亡。随后我们陆续在附近海区和养殖区域内的锯缘青蟹和脊尾白对虾中发现了sp.感染, 并已确定该寄生虫是浙江沿海海水养殖青蟹“黄水病”和养殖脊尾白对虾大规模死亡的的重要病原之一。后来, Li等(2008)在我国广东汕头的养殖锯缘青蟹中也报道发现了感染, 这是迄今第一次在低盐环境(<9)中发现并报道的感染。

在我国发现的常见生活史形态已确定包括滋养体(单核或多核)和孢子阶段; 然而, 由于目前还没有实现实验室内连续培养, 该种的完整生活史目前尚不清楚。初步基因片断(SSU rDNA 和 ITS1)序列分析结果表明, 感染我国舟山群岛附近海域三疣梭子蟹、锯缘青蟹和脊尾白对虾的sp.是同一种; 而且与美国兰蟹中发现的sp.具有较近的分子种系演化关系。因此, 我们可以借鉴美国兰蟹中sp.的研究进展, 对我国发现的这种sp.的完整生活史和传播方式进行系统研究; 并通过与典型种和其他sp.的生活史和分子种系演化关系进行比较研究, 以期对我国发现的sp.正式命名并确定其系统分类地位。另外, 该病在围塘老化、水交换差的池塘容易发生; 在7—9月高水温期以及在温度盐度环境变化较大的梅雨季节和台风季节也容易发病。但具体哪些环境因子与其在该区域的传播流行相关, 以及相关环境因子的具体作用机制都有待进一步的调查研究。我国集约工厂化养殖是虾蟹类的主要产业模式, 流行性疾病在这种养殖系统中可能更易于传播扩散。因此我们更迫切需要系统研究在我国发现的的生活史和传播、扩散途径, 以期减少直接经济损失和由于滥用抗生素和杀虫剂等而造成的环境污染。

7 结语

寄生性甲藻(parasitic dinoflagellates)广泛寄生于甲壳类动物和藻类等体内(Cachon, 1987; Shields, 1994; Coats, 1999), 是目前国际上海洋微型生物研究的新热点之一。甲壳类寄生性甲藻血卵涡鞭虫(spp.)流行和宿主范围广、宿主死亡率高, 给虾蟹类渔业生产带来的危害堪比虾类白斑综合症病毒(white spot syndrome virus, WSSV)病和龙虾类高夫败血病(Gaffekemia), 已开始受到国外越来越多研究者的重视(Stentiford, 2005)。而且不仅是海水甲壳类的重要病原微生物, 近来也被有些研究者归类为非典型性有害藻华物种(Harmful algal bloom, HAB)(Burkholder, 2006; Frischer, 2006)。虾蟹类养殖是我国沿海地区水产养殖业的支柱产业, 流行性疾病的暴发会严重影响到海产养殖业的可持续发展。为此我们在关注常见流行性海洋病原微生物的同时, 也应该重视诸如寄生性甲藻等这些原来不具备流行条件, 而随着近海海水环境的变化而逐渐流行起来的新兴海洋病原微生物, 并开展系统的调查研究。

许文军, 绳秀珍, 徐汉祥等, 2007a. 血卵涡鞭虫在养殖锯缘青蟹中的寄生. 中国海洋大学学报,37(6): 916—920

许文军, 施慧, 徐汉祥等, 2007b.养殖梭子蟹血卵涡鞭虫感染的初步研究. 水生生物学报, 31(5): 27—32

许文军, 谢建军, 施慧等, 2010. 池塘养殖脊尾白虾感染血卵涡鞭虫的研究. 海洋与湖沼, 41(3): 321—329

孟庆显, 俞开康, 1996. 鱼虾蟹贝疾病诊断与防治. 北京: 中国农业出版社, 1—367

查智辉, 施慧, 许文军等, 2011. 血卵涡鞭虫单克隆抗体制备及初步应用. 水产学报, 35(5): 780—786

施慧, 张静, 谢建军等, 2010. 环介导恒温扩增技术检测血卵涡鞭虫. 中国水产科学, 17(5): 1028—1035

施慧, 许文军, 徐汉祥, 2008.三疣梭子蟹感染血卵涡鞭虫PCR检测方法的建立. 上海水产大学学报, 17(1): 28—33

谢建军, 许文军, 施慧等, 2009. 海产蟹类血卵涡鞭虫病间接荧光抗体快速检测技术. 水产学报, 33(1): 126—131

Anderson D M, Aubrey D G, Tyler M A, 1982. Vertical and horizontal distributions of dinoflagellate cysts in sediments.Limnology and Oceanography, 27: 757—765

Appleton P L, Vickerman K, 1998.cultivation and developmental cycle in culture of a parasitic dinoflagellate (sp.) associated with mortality of the Norway lobster () in British waters. Parasitology,116: 115—130

Bower S M, Meyer G R, Phillips A, 2003. New host and range extension of bitter crab syndrome inspp. caused bysp.. Bulletin of the European Association of Fish Pathologists, 23: 86—91

Briggs R P, McAliskey M, 2002. The prevalence ofinfrom the western Irish Sea. Journal of the Marine Biologicalof the United Kingdom,82: 427—433

Burkholder J M, Azanza R V, Sako Y, 2006. The ecology of harmful dinoflagellates. In: Graneli E, Turner J T eds. Ecology of Harmful Algae. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 53—66

Cachon J, Cachon M, 1987. Parasitic dinoflagellates. In: Taylor F J R ed. The biology of dinoflagellate. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 571—610

Chatton É, Poisson R, 1931. Sur l’existence, dans le sang des Crabes, de Péridiniens parasites:n.g., n.sp. (Syndinidae). Comptes Rendus des Séances de la Société de Biologie Paris,105: 553—557

Coats D W, 1999. Parasitic life styles of marine dinoflagellates.Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, 46: 402—409

Coffey A H, Li C, Shields J D, 2012. Effects of salinity on developmental ofinfections in blue crabs,. Journal of Parasitology, 98(3): 536— 542

Dawe E, 2002. Trends in the prevalence of bitter crab disease caused bysp. in snow crab () through out the Newfoundland and Labrador continental shelf. In: Crabs in Cold Water Regions: Biology, Management, and Economics, Alaska Sea Grant Report AK-SG-02-01, Alaska Sea Grant Program. University of Alaska, Fairbanks, AK: 385—400

Eaton W D, Love D C, Botelho C, 1991. Preliminary results on the seasonality and life cycle of the parasitic dinoflagellate causing Bitter Crab Disease in Alaskan Tanner crabs (). Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 57: 426—434

Field R H, Appleton P L, 1995. A-like infection of the Norway lobster: observations on pathology and progression of infection. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 22: 115—128

Field R H, Chapman C J, Taylor A C, 1992. Infection of the Norway lobsterby a-like species of dinoflagellate on the west coast of Scotland. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 13: 1—15

Field R H, Hills J M, Atkinson R J A, 1998. Distribution and seasonal prevalence ofsp. infection of the Norway lobster () around the west coast of Scotland. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 55: 846—858

Frischer M E, Lee R F, Sheppard M A, 2006. Evidence for a free-living life stage of the blue crab parasitic dinoflagellate,sp.. Harmful Algae,5: 548—557

Gruebl T, Frischer M E, Sheppard M, 2002. Development of an 18S rRNA genetargeted PCR based diagnostic for the blue crab parasitesp.. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 49: 61—70

Hallegraeff G M, 1993. A review of harmful algal blooms and their apparent global increase. Phycologia,32: 79—93

Hudson D A, Adlard R D, 1996. Nucleotide sequence determination of the partial SSU rDNA gene and ITS1 region ofcf.and-like dinoflagellates. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 24: 55—60

Hudson D A, Adlard R D, 1994a. PCR-techniques applied tospp and-like dinoflagellates in decapod crustaceans. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 20: 203—206

Hudson D A, Lester R J G, 1994b. Parasites and symbionts of wild mud crabs(Forskal) of potential significance in aquaculture. Aquaculture, 120: 183—199

Hudson D A, Shields J D, 1994c.n. sp., a parasitic dinoflagellate of the sand crabfrom Moreton Bay, Australia. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 19: 109—119

Johnson P T, 1986. Parasites of benthic amphipods: dinoflagellates (:). Fishery Bulletin US,84: 605—614

Latrouite D, Morizur Y, Noël P, 1988. Mortalite duprovoquee par le dinoflagellate parasite:sp.. Cons Int Explor Mer, CM, K: 32

Li C, Miller T L, Small H J, 2011a. In vitro culture and developmental cycle of the parasitic dinoflagellatesp. from the blue crab. Parasitology, 138: 1924—1934

Li C, Shields J D, Miller T L, 2010. Detection and quantification of the free-living stage of the parasitic dinoflagellatespin laboratory and environmental samples. Harmful Algae,9: 515—521

Li C, Wheeler K N, Shields J D, 2011b. Cannibalism is not an effective route of transmission forsp. in the blue crab,. Disease of Aquatic Organism, 96: 249—258

Li Y, Xia X, Wu Q,2008. Infection withsp. in mud crabscultured in low salinity water in southern China. Diseases of Aquatic Organism, 82: 145— 150

Love D C, Rice S D, Moles D A, 1993.Seasonal prevalence and intensity of Bitter Crab dinoflagellate infection and host mortality in Alaskan Tanner crabsfrom Auke Bay, Alaska, USA. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 15: 1—7

MacLean S A, Ruddell C L, 1978. Three new crustacean hosts for the parasitic dinoflagellate Hematodinium perezi (Dinoflagellata: Syndinidae). Journal of Parasitology, 64: 158—160

Messick G A, Jordan S J, Van Heukelem W F, 1999. Salinity and temperature effects onsp. in the blue crab. Journal of Shellfish Research, 18: 657—662

Messick G A, Shields J D, 2000. Epizootiology of the parasitic dinoflagellatesp. in the American blue crab. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 43: 139—152

Messick G A, Sindermann C J, 1992. Synopsis of principal diseases of the blue crab,NOAA NMFS Tech Memo NMFS-F/NEC-88, Washington, D.C.:24

Messick G A, 1994.infections in adult and juvenile blue crabsfrom coastal bays of Maryland and Virginia, USA. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms,19: 77—82

Meyers T R, Botelho C, Koeneman T M, 1990. Distribution of bitter crab dinoflagellate syndrome in southeast Alaskan tanner crabs,. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 9: 37—43

Meyers T R, Koeneman T M, Botelho C, 1987. Bitter crab disease: a fatal dinoflagellate infection and marketing problem from Alaskan tanner crabs,. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 3: 195—216

Meyers T R, Morado J F, Sparks A K, 1996. Distribution of bitter crab syndrome in tanner crabs (,) from the Gulf of Alaska and the Bering Sea. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 26: 221—227

Nagle L, Place A R, Schott E J, 2009. Real-time PCR-based assay for quantitative detection ofsp. in the blue crab. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 84, 79—87

Newman M W, Johnson C A, 1975. A disease of blue crabs () caused by a parasitic dinoflagellate,sp.. Journal of Parasitology, 63: 554—557

Ris H, Kublai D F, 1974. An unusual mitotic mechanism in the parasitic protozoansp.. Journal of Cell Biology,60: 702—720

Sheppard M, Walker A, Frischer M E, 2003. Histopathology and prevalence of the parasitic dinoflagellatesp., in crabs (,,,,) from a Georgia estuary.Journal of Shellfish Research, 22: 873—880

Shields J D, Squyars C M, 2000. Mortality and hematology of blue crabs,, experimentally infected with the parasitic dinoflagellate. Fish Bulletin,98:139—152

Shields J D, Taylor D M, O’Keefe P G, 2007. Epidemiological determinants in outbreaks of bitter crab disease (sp.) in snow crabs,from Newfoundland, Canada. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 77: 61—72

Shields J D, Taylor D M, Sutton S G, 2005. Epizootiology of bitter crab disease (sp.) in snow crabs,, from Newfoundland, Canada. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 64: 253—264

Shields J D, 1992. Parasites and symbionts of the crabfrom Moreton Bay, eastern Australia. Journal of Crustacean Biology, 12: 94—100

Shields J D, 1994. The parasitic dinoflagellates of marine crustaceans. Annual Review of Fish Diseases,4: 241—271

Small H J, Shields J D, Hudson K L, 2007. Molecular detection ofsp. infecting the blue crab. Journal of Shellfish Research, 26: 131—139

Small H J, Shields J D, Reece K S, 2012. Morphological and molecular characterization of(Dinophyceae: Syndininiales), a dinoflagellate parasite of the harbour crab,. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, 59: 54—66

Small H J, Wilson S, Neil D M, 2002. Detection of the parasitic dinoflagellatein the Norway lobsterby ELISA. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 52:175—177

Smayda T J, 1997. Bloom dynamics: physiology, behavior, trophic effects.Limnology and Oceanography, 2: 1132—1136

Stentiford G D, Evans M G, Bateman K, 2003. Coinfection by a yeast-like organism ininfected European edible crabsand velvet swimming crabsfrom the English Channel. Diseases of Aquatic Organism, 54: 195—202

Stentiford G D, Green M, Bateman K, 2002. Infection by a-like parasitic dinoflagellate causes Pink Crab Disease (PCD) in the edible crab. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 79: 179—191

Stentiford G D, Neil D M, Atkinson R J A, 2000. An analysis of swimming performance in the Norway lobster,L. infected by a parasitic dinoflagellate of the genus. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology,247: 169—181

Stentiford G D, Neil D M, Atkinson R J A, 2001a. The relationship ofinfection prevalence in a Scottishpopulation to seasonality, moulting and sexICES Journal of Marine Sciences, 58: 814—823

Stentiford G D, Neil D M, Coombs G H, 2001b. Development and application of an immunoassay diagnostic technique for studyinginfections inpopulations. Diseases of Aquatic Organism, 46: 223—229

Stentiford G D, Shields J D, 2005. A review of the parasitic dinoflagellatesspecies and-like infections in marine crustaceans. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 66: 47—70

Tagatz M E, 1968. Growth of juvenile blue crabs,Rathbun, in the St. Johns River, Florida. Fishery Bulletin, 67: 281—288

Taylor A C, Field R H, Parslow-Williams P J, 1996. The effects of Hematodinium sp.-infection on aspects of the respiratory physiology of the Norway lobster,(L.). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 207: 217—228

Taylor D M, Khan R A, 1995. Observations on the occurrence ofsp. (Dinoflagellata: Syndinidae): the causative agent of Bitter Crab disease in the Newfoundland snow crab (). Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 65: 283—288

Walker A N, Lee R F, Frischer M E, 2009. Transmission of the parasitic dinoflagellatesp. infection in blue crabsby cannibalism. Diseases of Aquatic Organism, 85: 193—197

Wilhelm G, Mialhe E, 1996. Dinoflagellate infection associated with the decline ofcrab populations in France.Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 26: 213—219

Xu W, Xie J, Shi H, 2010.infections in cultured ridgetail white prawns,, in eastern China. Aquaculture,300: 25—31

REVIEW ON PARASITIC DINOFLAGELLATESSPP. IN MAJOR MARINE CRUSTACEANS

LI Cai-Wen1, XU Wen-Jun2

(1. Key Lab of Marine Ecology and Environmental Sciences, Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China; 2. Key Lab of Mariculture and Enhancement, Marine and Fisheries Research Institute of Zhejiang Province, Zhoushan 316100, China)

is a type of parasitic dinoflagellates infecting marine crustacea. It would affect severely various stocks of commercial valuable crustacean fisheries worldwidely. Recently,was found in southeast coast of China and had caused epidemic diseases in several cultured crustaceans, such as,, and, and was identified the causative agent of certain epidemic diseases. However, current research in China focused on field survey, pathogen identification, and diagnostics, little is known about the life cycle and transmission of this dinoflagellate. Understanding its life cycle and transmission is critical to control the spreading of the epidemic pathogen. Thereby, we review the biology and ecology ofspp. in marine crustaceans, focusing on taxonomy, life cycle, transmission, epidemiology etc., to highlight key aspects of the pathogen in the future research and practical strategies to control the spreading of the disease.

parasitic dinoflagellates; life cycle; transmission; dinospores; aquaculture

10.11693/hyhz20120905001

* 国家基金委创新研究群体科学基金项目, 41121064号; 国家基金委青年科学基金项目, 41206145号; 浙江省科技厅院所专项项目, 2011F30017号; 浙江省舟山市科技局项目, 2012C23003号; 海洋公益性行业科研专项经费项目, 201005015-1号。

李才文, 研究员, 博士生导师, E-mail: cwli@qdio.ac.cn

2012-09-05,

2012-12-10

P735