Evidence of increasing L1014F kdr mutation frequency in Anopheles gambiae s.l. pyrethroid resistant following a nationwide distribution of LLINs by the Beninese National Malaria Control Programme

Nazaire Aïzoun, Rock Aïkpon, Martin Akogbéto

1Centre de Recherche Entomologique de Cotonou (CREC), 06 BP 2604, Cotonou, Bénin

2Faculté des Sciences et Techniques, Université d’Abomey Calavi, Calavi, Bénin

Evidence of increasing L1014F kdr mutation frequency in Anopheles gambiae s.l. pyrethroid resistant following a nationwide distribution of LLINs by the Beninese National Malaria Control Programme

Nazaire Aïzoun1,2*, Rock Aïkpon1,2, Martin Akogbéto1,2

1Centre de Recherche Entomologique de Cotonou (CREC), 06 BP 2604, Cotonou, Bénin

2Faculté des Sciences et Techniques, Université d’Abomey Calavi, Calavi, Bénin

PEER REVIEW

Peer reviewer

Dr. Alex Asidi, Malaria Centre, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street, London WC1 7HT, United Kingdom.

Tel: 00 (44) (0) 7405880349

E-mail: alex.asidi@yahoo.com

Comments

The authors have clearly shown a widespread kdr frequency in the transect south-north Benin which have increased even after the distribution of LLINs. The effect of selection pressure after a large scale distribution of LLINs has confirmed previous reports by Czeher et al. (2008) on an increase Leu-Phe kdr mutation in Niger following a countrywide LLINs implementation. The study is important in its field.

Details on Page 242

Objective:To determine the susceptibility status to pyrethroid in Anopheles gambiae s.l. (An. gambiae), the distribution of kdr “Leu-Phe” mutation in malaria vectors in Benin and to compare the current frequency of kdr “Leu-Phe” mutation to the previous frequency after long-lasting insecticide treated nets implementation.

Resistance, Insecticide, Vectors, CDC bioassay, Leu-Phe kdr mutation

1. Introduction

There were an estimated 216 million episodes of malaria in 2010, with 149 million to 274 million cases. Approximately 81%, or 174 million cases, were in the African Region, with the Southeast Asian Region accounting for another 13%[1]. There were also an estimated 655 000 malaria deaths in 2010, of which 91% were in the African Region. Approximately 86% of malaria deaths globally were of children under 5 years of age[1]. So, malaria remains one of the most critical public health challenges for Africa despite intense national and international efforts[2].

The intensive use of insecticide in the malaria control activities means that widespread mosquito insecticide resistance could have a devastating effect on the planned upscaling of the vector control activities[3].

In many African countries, malaria mosquitoes were already resistant to pyrethroids. For instance, pyrethroidresistance inAnopheles gambiaes.s. (An. gambiae) has already been described in Benin[4-6].

Malaria vector resistance to insecticides in Benin is conferred by two main mechanisms: (1) alterations at site of action in the sodium channel,viz.thekdrmutations and (2) an increase of detoxification and/or metabolism through high levels of multi-function oxidases, non-specific esterases and glutathione S-transferases[4-7].

The Beninese National Malaria Control Programme has been implemented. Large-scale and free long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) (OlysetNet) were distributed since July 2011 throughout the country to increase coverage of LLINs. Information on susceptibility to pyrethroid insecticides used in public health in Benin and the underlying mechanisms being investigated are crucial. This will properly inform control programs of the most suitable insecticides to use and facilitate the design of appropriate resistance management strategies.

The aim of this study is to determine the susceptibility status, pyrethroid resistance levels inAn. gambiaeMalanville, Parakou, Bohicon and Suru-lere populations to permethrin and deltamethrin using CDC (Center for Disease Control and Prevention) bottle bioassays, to evaluate the presence and extent of the distribution of thekdrmutation within and among theseAn. gambiaes.l. populations and to compare the current frequency ofkdr“Leu-phe” mutation to the previous frequency in malaria vectors in the southnorth transect Benin after LLINs implementation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area

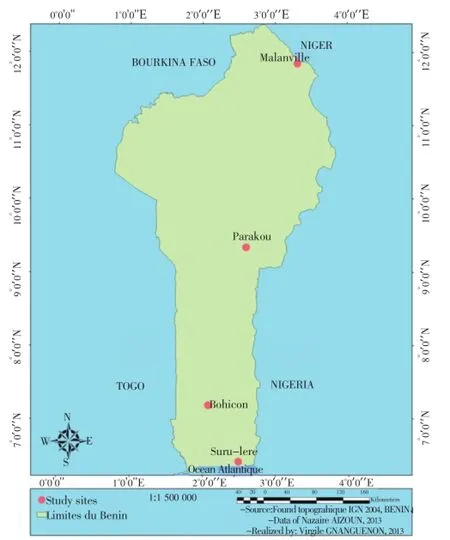

The study was carried out in some localities, following a south-north transect. Four contrasting localities of Benin were selected for mosquito collection on the basis of variation in agricultural production, use of insecticides and/or ecological settings (Figure 1). The localities are as follows. Bohicon is located in the middle part of the country where the farmers used significant amounts of pyrethroids and organophosphates for cotton protection or to control agricultural pests. Parakou, an urban vegetable growing area located in the north of Benin. Malanville is a rice growing area located near the Niger River. Suru-lere is an urban locality in Cotonou district located in southern Benin.

The choice of the study sites took into account the economic activities of populations, their usual protection practices against mosquito bites, and peasant practices to control farming pests. The southern zone (Cotonou) is characterized by a tropical coastal Guinean climate with two rainy seasons (April-July and September-November). The mean annual rainfall is over 1 500 mm. The middle part of the country (Bohicon) is characterized by a Sudano-Guinean climate with an average rainfall of 1 000 mm per year. The northern zone (Parakou and Malanville) is characterized by a Sudanian climate with only one rainy season per year (May to October) and one dry season (November-April). The temperature ranges from 22 to 33 °C with the mean annual rainfall of 1 300 mm.

Figure 1. Map of the study area.

2.2. Sample collection

From March 2012 to November 2012, larvae and pupae ofAn. gambiaemosquito were collected several times per year,i.e.at the beginning and the end of rainy season from a wide range of breeding sites (puddles, shallow wells, gutters and rice fields) in Malanville, Parakou, Bohicon districts and in Suru-lere locality of Cotonou district. All larvae were brought back to laboratory of Centre de Recherche Entomologique de Cotonou for rearing. Emerging adult female mosquitoes were used for insecticide susceptibility tests. A susceptible strain ofAn. gambiaeKisumu was used as reference strain for bioassays.

2.3. Insecticide susceptibility tests

FemalesAn. gambiaeaged 2 to 5 d old were exposed to CDC diagnostic dosage of various insecticides according to the CDC protocol[8]. The following insecticides were tested: permethrin (21.5 µg per bottle) and deltamethrin (12.5 µg per bottle). Mosquitoes were exposed for 2 h to insecticidetreated bottles and monitored at different time intervals (15, 30, 35, 40, 45, 60, 75, 90, 105 and 120 min). This allowed us todetermine the total percent mortality (Y axis) against time (X axis) for all replicates using a linear scale. All susceptibility tests were conducted in the Centre de Recherche Entomologique de Cotonou laboratory at (25±2) °C and 70 to 80% relative humidity.

Dead and surviving mosquitoes were separately stored in individual tubes with silicagel and preserved at -20 °C in the laboratory for further molecular characterization. The choice of permethrin was justified by the insecticide used on OlysetNets that were distributed free by the national malaria control program in July 2011 across all the country whereas we used deltamethrin, an insecticide of same class as permethrin to assess its cross-resistance with this product.

2.4.PCRdetection of species and the kdr mutation

At the end of CDC bioassays, PCR tests for species identification was performed to identify the members ofAn. gambiaecomplex collected from each site[9]. PCR for the detection of thekdr“Leu-phe” mutation was carried out on dead and aliveAn. gambiaemosquitoes as described by Martinez-Torreset al[10].

2.5. Statistical analysis

The resistance status of mosquito samples was determined according to the CDC criteria[8,11]. The susceptibility thresholds at the diagnostic time of 30 min for pyrethroids are shown below:

Mortality rate=100%: the population is fully susceptible.

Mortality rate<100%: the population is considered resistant to the tested insecticides.

Molecular results (kdrfrequencies) were correlated with the results of insecticide susceptibility tests performed with CDC method from each of the districts surveyed.

ANOVA test was performed with mortality rate as the dependent variable and the localities as a covariate. ANOVA test was also performed withkdrfrequency as the dependent variable and the localities as a covariate.

3. Results

3.1. Susceptibility ofAn. gambiaes.l. populations to permethrin and deltamethrin

Table 1 shows that Kisumu strain (control) confirmed its susceptibility status as a reference strain. All females mosquitoes ofAn. gambiaeKisumu which were exposed to CDC bottles treated with permethrin 21.5 µg/bottle and deltamethrin 12.5 µg/bottle were dead and none of them can fly after 30 min, which represented susceptibility threshold time or diagnostic time clearly defined by CDC protocol. That confirmed this strain was fully susceptible to these products. A non neglected proportion ofAn. gambiaeMalanville and Suru-lere populations, 100% and 13.93% respectively, after 30 min exposure to CDC bottles treated with deltamethrin, continued to fly in these bottles. That showed these populations were resistant to this product.An. gambiaeParakou and Bohicon populations after 30 min exposure to CDC bottles treated with permethrin 7.5% and 12.5% respectively, continued again to fly in these bottles. That also showed these populations were resistant to this product (Table 1).

Table 1 Mortality of An. gambiae from the districts of Malanville, Parakou, Bohicon and Suru-lere locality of Cotonou district after 2 h exposure to permethrin (21.5 µg/bottle) and deltamethrin (12.5 µg/bottle).

Univariate logistic regression performed with mortality rate as the dependent variable and localities as a covariate with ANOVA test showed that the phenotypic resistance to permethrin and deltamethrin was associated with the localities (P<0.05) on the one hand. Univariate logistic regression performed withkdrfrequency as the dependent variable and localities as a covariate with ANOVA test showed that highkdrfrequency was associated with the localities (P<0.05) on the other hand.

3.2. Species of An. gambiae

Mosquitoes from CDC bioassay were analysed by PCR for identification of sibling species amongAn. gambiaes.l. complex. PCR revealed 100% of mosquitoes tested wereAn. gambiaes.s. (Table 2).

Table 2 Species identification and kdr frequency in An. gambiae s.l. from CDC bioassays.

3.3. Detection of resistance genes

The L1014Fkdrmutation was found inAn. gambiaes.s. Malanville and Parakou at various allelic frequencies (Table 2). The increase ofkdrallelic frequency was positively correlated with CDC bioassays data.

4. Discussion

The resistance level to deltamethrin observed inAn. gambiaeMalanville was higher than the one observed withAn. gambiaeSuru-lere. It was also higher than the resistance level to permethrin observed inAn. gambiaeParakou and Bohicon. Similar results were already reported by Aïzounet al[7]. In fact, Malanville is a rice growing area where no insecticidal products are generally used to control agricultural pests comparatively to the vegetable growing area of Parakou and cotton growing area of Bohicon where various insecticidal products are used for this purpose.

The alterations at site of action in the sodium channel,viz.thekdrmutations inAn. gambiaes.l. mosquitoes from Malanville were not the same resistance mechanism involved in these mosquitoes populations. A previous study carried out by Djègbéet al.showed higher oxidase activity inAn. gambiaes.l. Malanville populations compared to the Kisumu susceptible strain in 2009[5]. In addition, a recent study carried out by Aïzounet al.onAn. gambiaeKandi in Alibori province including Malanville district showed that the synergist assay with piperonyl butoxide, an inhibitor of cytochrome P450 monooxygenases, played a role in the deltamethrin resistance observed in Kandi[7].

In the cuurent study,kdrfrequencies recorded inAn. gambiaeParakou and Malanville were 74% and 90% respectively. Thekdrfrequencies recorded inAn. gambiaeParakou and Malanville in 2007 by Corbelet al.were 20% and 6% respectively[12]. These results showed thatkdrfrequencies in theseAn. gambiaepopulations had significantly increased after five years. This is consistent with previous observation reporting an increase of thekdr1014F frequency inAn. gambiaefollowing a nationwide distribution of LLINs in Niger[13].

In the rice field area of Malanville, the increase in resistance to deltamethrin can be attributed to the augmentation of the 1014Fkdrprevalence even if deltamethrin is a cyanopyrethroid and detoxifying enzymes such as cytochrome P450 monooxygenases. The sudden increase inkdrfrequency and pyrethroid resistance is worrying considering the relatively low amount of insecticide use in Malanville. It is possible thatAn. gambiaepopulations carrying thekdrmutation might have migrated through active or/and passive ways from bordering countries (e.g.Niger, Nigeria) due to intense traffic and exchanges in this locality[5].

Higher mortality rates were observed with permethrin compared to DDT inAn. gambiaeParakou and Bohicon populations and may be explained by the presence of an additional resistance mechanism in Benin (e.g.“Leu-Ser”mutation) which might confer higher resistance to DDT than to permethrin[14].

Deltamethrin resistance inAn. gambiaeSuru-lere may be explained by increased use of household insecticide and availability of xenobiotics for larval breeding sites in the urban. It was one of the possible factors selecting for pyrethroid resistance inAn. gambiaein urban areas.

In conclusion, pyrethroid resistance is widespread in malaria vector in Benin andkdrmutation is the main resistance mechanism involved. The L1014Fkdrmutation frequency inAn. gambiaes.l. which is resistant to pyrethroid from the south-north transect Benin may increase after a nationwide LLINs implementation. More attention may be paid for the future success of malaria control programmes based on LLINs with pyrethroids in the country.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche Scientifique, Benin for supporting the doctoral training of Nazaire. We also thank Dr. William G. BROGDON from CDC Atlanta who supplied us the reagents used for CDC bioassays. The authors would also like to thank Frédéric OKE-AGBO for statistical analysis, Damien TODJINOU for providing technical assistance and Virgile GNANGUENON who contributed to the mapping. This research was funded by the President’s Malaria Initiative of the U.S. Government through USAID and the Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche Scientifique, Benin.

Comments

Background

The spread of pyrethroid resistance in malaria vectors is increasingly becoming a cause of concern especially in endemic countries where insecticide treated nets were the basic tool for vector control. Several published reports on pyrethroid resistance inAnophelesmosquitoes in Benin have raised an alarm to the threat it causes to the future usefulness of insecticide treated nets for effective malaria control.

Research frontiers

The present study evaluated the status of pyrethroid resistance, the distribution ofkdrmutation and compared the presentkdrallelic frequencies to that of previous reports before the distribution of LLINs took place. Significant increase frequencies ofkdrmutation have been evidenced in areas of Malanville and Parakou previously with remarkablylow frequencies.

Related reports

Pyrethroid resistance has been documented inAn. gambiaes.l. in South Benin with Leu-Phekdrmutation as the main resistance mechanism with 80% frequency (Corbelet al., 2007). The experimental huts reducing efficacy of ITNs and IRS against pyrethroid resistant mosquitoes was reported (N’Guessanet al., 2007). Another report in South Benin showed evidence of loss of household protection by insecticide treated nets in areas of pyrethroid resistance (Asidiet al., 2012).

Innovations and breakthroughs

Pyrethroid resistance is a serious concern forAnophelescontrol in South Benin. In the present paper, the authors showed evidence that those populations ofAn. gambiaefrom Malanville (North Benin) had lost their susceptibility to deltamethrin. And thekdrmutation is rapidly spreading with increased frequency in the northern and central (Parakou) parts of Benin despite a scaling up of LLINs distributions nationwide.

Applications

Good knowledge on the status of insecticide resistance would help to prevent vector control failure and the right choice of insecticides. The findings from this study suggested that resistance monitoring would be best advised and helpful to the national malaria control program. In the meantime, investigations on alternatives to pyrethroids would be an indicative route to develop effective tools for insecticide resistance management strategies.

Peer review

The authors have clearly shown a widespreadkdrfrequency in the transect south-north Benin which have increased even after the distribution of LLINs. The effect of selection pressure after a large scale distribution of LLINs has confirmed previous reports by Czeheret al. (2008) on an increase Leu-Phekdrmutation in Niger following a countrywide LLINs implementation. The study is important in its field.

[1] World Health Organization. World malaria report 2011. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [online] Available from: http://www.who.int/malaria/ world_malaria_report_2011/en/. [Accessed on 23 Jun, 2013]

[2] World Health Organization. Launch of the global plan for insecticide resistance management in malaria vectors 2012. Geneva: WHO; 2012. [online] Available from: http://www.who.int/ malaria/vector_control/gpirm_event_report_2012.pdf. [Accessed on 23 Oct, 2013]

[3] Verhaeghen K, Bortel WV, Roelants P, Okello PE, Talisuna A, Coosemans M. Spatio-temporal patterns in kdr frequency in permethrin and DDT resistant Anopheles gambiae s.s. from Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2010; 82(4): 566-573.

[4] Djogbénou L, Pasteur N, Akogbéto M, Weill M, Chandre F. Insecticide resistance in the Anopheles gambiae complex in Benin: a nationwide survey. Med Vet Entomol 2011; 25(3): 256-267.

[5] Djègbé I, Boussari O, Sidick A, Martin T, Ranson H, Chandre F, et al. Dynamics of insecticide resistance in malaria vectors in Benin: first evidence of the presence of L1014S kdr mutation in Anopheles gambiae from West Africa. Malar J 2011; 10: 261.

[6] Aïzoun N, Ossè R, Azondekon R, Alia R, Oussou O, Gnanguenon V, et al. Comparison of the standard WHO susceptibility tests and the CDC bottle bioassay for the determination of insecticide susceptibility in malaria vectors and their correlation with biochemical and molecular biology assays in Benin, West Africa. Parasit Vectors 2013; 6(1): 147.

[7] Aïzoun N, Aïkpon R, Padonou GG, Oussou O, Oké-Agbo F, Gnanguenon V, et al. Mixed-function oxidases and esterases associated with permethrin, deltamethrin and bendiocarb resistance in Anopheles gambiae s.l. in the south-north transect Benin, West Africa. Parasit Vectors 2013; 6(1): 223.

[8] Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center. Methods in Anopheles research. 2nd ed. Atlanta: Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center; 2010.

[9] Scott JA, Brogdon WG, Collins FH. Identification of single specimens of the Anopheles gambiae complex by the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1993; 49(4): 520-529.

[10] Martinez-Torres D, Chandre F, Williamson MS, Darriet F, Berge JB, Devonshire AL, et al. Molecular characterization of pyrethroid knockdown resistance (kdr) in major malaria vector An. gambiae s.s. Insect Mol Biol 1998; 7(2):179-184.

[11] Brogdon WG, McAllister JC. Simplification of adult mosquito bioassays through use of time-mortality determinations in glass bottles. J Am Mosq Control Assoc 1998; 14(2):159-164.

[12] Corbel V, N’Guessan R, Brengues C, Chandre F, Djogbenou L, Martin T, et al. Multiple insecticide resistance mechanisms in Anopheles gambiae and Culex quinquefasciatus from Benin, West Africa. Acta Trop 2007; 101(3): 207-216.

[13] Czeher C, Labbo R, Arzika I, Duchemin JB. Evidence of increasing Leu-Phe knockdown resistance mutation in Anopheles gambiae from Niger following a nationwide long-lasting insecticidetreated nets implementation. Malar J 2008; 7: 189.

[14] N’Guessan R, Boko P, Odjo A, Chabi J, Akogbeto M, Rowland M. Control of pyrethroid and DDT resistant Anopheles gambiae by application of indoor residual spraying or mosquito nets treated with a long-lasting organophosphate insecticide, chlorpyrifosmethyl. Malar J 2010; 9: 44.

10.1016/S2221-1691(14)60238-0

*Corresponding author: Nazaire Aïzoun, Centre de Recherche Entomologique de Cotonou, 06 BP 2604, Cotonou, Bénin; Faculté des Sciences et Techniques, Université d’Abomey Calavi, Calavi, Bénin.

Tel: (229) 95317939

E-mail: aizoun.nazaire@yahoo.fr

Article history:

Received 12 Dec 2013

Received in revised form 20 Dec, 2nd revised form 25 Dec, 3rdd revised form 30 Dec 2013

Accepted 20 Jan 2014

Available online 28 Mar 2014

Methods:Larvae and pupae of An. gambiae s.l. mosquitoes were collected from the breeding sites in Littoral, Zou, Borgou and Alibori provinces. CDC susceptibility tests were conducted on unfed females mosquitoes aged 2-5 d old. An. gambiae mosquitoes were identified to species using PCR techniques. Molecular assays were also carried out to identify kdr mutations in individual mosquitoes.

Results:The results showed that An. gambiae Malanville and Suru-lere populations were resistant to deltamethrin. Regarding An. gambiae Parakou and Bohicon populations, they were resistant to permethrin. PCR revealed 100% of mosquitoes tested were An. gambiae s.s. The L1014F kdr mutation was found in An. gambiae s.s. Malanville and Parakou at various allelic frequencies. The increase of kdr allelic frequency was positively correlated with CDC bioassays data.

Conclusions: Pyrethroid resistance is widespread in malaria vector in Benin and kdr mutation is the main resistance mechanism involved. More attention may be paid for the future success of malaria control programmes based on LLINs with pyrethroids in the country.

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine2014年3期

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine2014年3期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine的其它文章

- An update on Ayurvedic herb Convolvulus pluricaulis Choisy

- Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella spp. in raw retail frozen imported freshwater fish to Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia

- Hesperidin as a preventive resistance agent in MCF-7 breast cancer cells line resistance to doxorubicin

- Anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory effects of Tagetes minuta essential oil in activated macrophages

- Long-term spatial memory and morphological changes in hippocampus of Wistar rats exposed to smoke from Carica papaya leaves

- Survey on cattle ticks in Nur, north of Iran