Liu Xiaodong:Drawn to Everyday People

By+JON+BURRIS

By the time I saw one of Liu Xiaodongs paintings in person, in the summer of 1995 at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, he was completing his Masters degree and was already a recognized member of what was called the New Generation artists. His work had been included in the infamous China Avant-garde exhibition at the National Gallery in 1989 but by the mid-1990s critics were applying the term neo-Realist to him, placing him in a different category from the Cynical Realists with whom he had previously been identified. Personally, I felt his work was so different; it belonged in a class by itself.

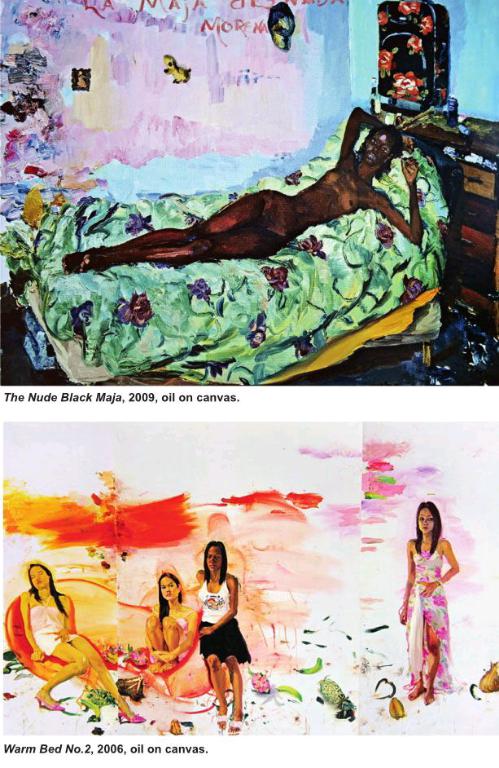

I can remember thinking that his figurative paintings of people, mostly friends, family, fellow students and artists, were as immediate and forceful as anything I had seen by any other contemporary Chinese artist. Lius paintings were honest and direct. Stylistically, they were expressionistic, full of energy and color, yet they were realistic enough to define their subjects: everyday people in settings anyone could relate to.

If they borrowed from anything, it was from the medium of film and photography that had a strong influence on Xiaodong given his friendships with Chinas sixth-generation filmmakers he had known in school. But Xiaodongs painted compositions seemed to catch his subjects in those in-between instances that get recorded by photographers trying to stop time; the exposures on either side of the chosen one that best defines the “decisive moment.”They didnt preserve moments, they were not narrative, they didnt represent any particular class or generation, they made no political statements, they were not clever or ironic. They were simply real.

Xiaodong began making photographs in 1984 as reference material for his paintings and, in part, as a way to record the developing relationship he was having with his future wife, the painter Yu Hong. While I had admired Xiaodongs work since meeting both he and Hong briefly at the Central Academy, we had never really talked until 2009 when I visited them both at their studios in Beijings 798 art district to photograph them for this book.

Occupying a single, nondescript building, their studios were quite separate and each utilitarian, even modest by comparison to many other studios I have been over the last couple of years. Xiaodongs smelled of fresh paint. He was working on a canvas that showed seven figures in a Muslim cafe. Scattered on a drafting table were snapshots he had made of individual Muslim men, women and children in disparate poses. Collectively, they comprised the painting in progress.

As I photographed him painting, he moved intensely between a palette covered in oils and his canvas, changing brushes by color as needed. His every move was deliberate and quick unlike some painters I have watched who are slow and studied. I was amazed at how quickly the details of the painting in front of me came into focus, and I was finally able to get a sense of why Xiaodong is such a prolific artist. He is compelled to paint; as if he can hardly wait to see for himself what the finished work will look like.

I commented on how intense he seemed. He joked that when he was a child, a fortune teller told him he would not live past the age of nineteen or twenty so he was working on borrowed time! He said he was traveling more to other countries like Thailand and Cuba. I asked if a healthy contemporary Chinese art market had made that possible. He laughed and said perhaps, but added that he had never been that concerned with the market. “Im still painting the same subjects I have always been drawn to, everyday people.”