Joel Bellassen:Sinology on the French Fast Track

RECALLING his decision in the 1970s to learn Chinese, consid- ered perhaps unusual at that time, Joel Bellassen, now Inspector-General of Chinese Language Teaching at Frances Ministry of Education (Inspecteur général de chinois), remarks that many people were astonished by his choice, since it was not out of selfinterest but out of conviction.

Joel Bellassens legendary life parallels the progress in bilateral relations between China and France. He was among the first batch of students sent to China after the establishment of diplomatic relations. On graduation, he became Frances first Chinese-language teacher at the kindergarten and primary school level. He was appointed as the very first Inspector-General of Chinese language teaching in 2006. Joel has since devoted himself to promoting Chinese language learning in France.

Attracted from Afar by the Mysteries of Chinese Language

Back in 1970, Joel Bellassen was a philosophy student. Diplomatic relations between the two countries had already been established, but Joel had no idea about Chinese culture, let alone any contact with Chinese studies. For him, China was as distant as the moon.

During his second year doing his MA, Frances higher education underwent reforms – and selecting a minor became a prerequisite for all students. Joel first chose Spanish, but quickly found that, being so close to French, it held no surprises for him. The Chinese written characters he frequently noticed on the door of the Chinese Department lured him, and he switched to learning Chinese.

In 1970s France, or even the whole Europe, learning Chinese provided few job opportunities. China had not opened its doors to the outside world, so study or travel in China was also still quite difficult.

Joel recalled, “It may seem a little strange that I chose to learn Chinese. But if you were familiar with the attraction of Chinas image, along with my personality, you would see it as a natural choice. China, like France, is a very ancient country with a long history . Both value their historical records and cultural heritage. French people pay great respect to countries with history. It was in this frame of mind that I started to learn this remote language.”

Since that was just after the May 1968 events in France had ended, and Chinas “cultural revolution” had commenced, many people thought his choice was related to politics. But he denies this. “My classmates and I never participated in any political events. The politics and those unusual times were not our motivation to learn the language.”

What most inspired Joel Bellassen was the distinctive differences between Chinese and European languages. Within the very first several classes, Chinese became a magnet pulling him along.

Joel Bellassen has always enjoyed adventure and learning different things. He has never followed the mainstream. After learning Chinese, he had been frequently asked the question by friends and family why he chose to learn this language. He felt proud for being special and gaining such attention. For him Chinese learning has never been a problem, but rather posed a challenge full of inspiration.

A Trip to the “Moon”

Joel Bellassens MA dissertation was on Chinese idioms. He explained and made notes on 1,000 of them. For him, these idioms are linguistic devices encapsulating charm, culture and philosophy.

His study originated in having to review some Chinese idioms assigned by a teacher for their winter vacation. They were asked to gain a good understanding and make sentences with them. He decided to research the idiom, Zuò jǐng guān tiān(literally means [a frog] sitting in a well, gazing at the sky) for he had been confused about the meaning of the idiom. When Joel returned to Paris, he went to a metro exit with a little note stating the proverbs literal meaning in French. He interviewed French passersby and solicited their views on its figural connotation. They all showed great interest on learning it was an ancient Chinese expression. They would think the meaning over and respond. Joel discovered that most of their guesses involved a frog living leisurely deep in a well and enjoying the view overhead, or meditating in comfort. They believed this idiom praised the frogs enjoyment of a tranquil life, acquiring philosophical insights – totally different from the Chinese meaning (of a narrow or limited worldview). From this, Joel Bellassen surmised that mutual understanding between the two different cultures might not be so easy.

After finishing his dissertation, Joel had to face the reality that his Chinese studies had come to an end. At that time, there were only 10 universities in France teaching Chinese, with 1,000 students studying it. He was momentarily at a loss as to what to do with Chinese, but later welcomed the prospective challenges.

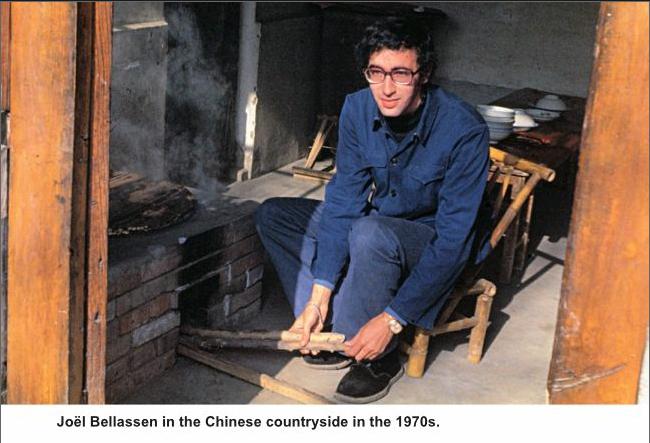

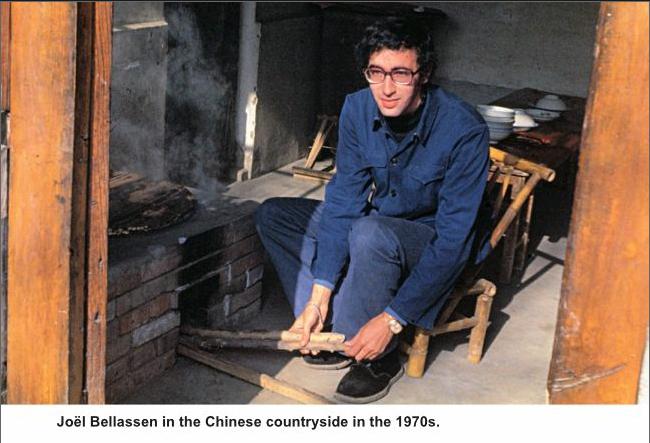

In 1973, cultural exchanges between China and France resumed, including student exchanges. The official batch, with the most people since 1965, consisted of 30 French students coming to China, with Joel Bellassen among them.

Today, French people can learn more about China through travel and books as well as other media. But in the 1970s, little information about China could be found in France. Joel was not able even to imagine what the country would be like at that time. Therefore, he was neither excited nor disappointed when he first arrived in Beijing. He just looked forward to exploring the city and the country.

Those two years in Beijing are indelible in his memory. In his Farewell to China: My impressions of China of the 1970s, Joel recorded his life in China and his friendships with Chinese people. For example, he recalled Zhang Pengpeng, who co-authored with him Méthode dinitiation à la langue et à lécriture chinoises, a book about learning Chinese characters.

Relations between China and France developed rapidly over those two years, laying a solid foundation for Joels career in Chinese-language research and its transmission back in France.

“Youll Definitely Come into Contact with China in the Future”

In 1978, China launched its reform and openingup policy. From then on, more French people became interested in Chinese language. Since his return to France, Joel has been teaching and popularizing the Chinese language. He gave Chinese classes in middle schools and universities. At the same time, he taught basic Chinese to children at lécole Alsacienne de Paris.

While teaching, Joel found Chinese language to be ideal for early childhood education. He believes writing Chinese characters helps in developing childrens coordination, sense of space, and organization skills. The four tones of Chinese language help to sharpen childrens listening skills, while deciphering proverbs or written characters trains their ability to think abstractly.

“The abilities we acquire from Chinese could never be obtained from European languages,” Joel said.“People used to consider Chinese as a complicated and difficult language only suitable for students at the stage of higher education. However, the French media followed closely on my teaching experiments at lécole Alsacienne de Paris and changed such opinions.”

China has become more involved in economic and cultural exchanges with the international community. Many Chinese people started going to France for study, while there has been an increasing number from France streaming into China for work and study. In 1984, the Association for Chinese Teachers in France was established, with Joel as the first president. In 1989, he began to teach Chinese at the Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales, and publishing his Chinese textbooks.

In 1985, Chinese language was taught in primary schools, making France the first European country to provide Chinese classes in primary and secondary schools. The number of Chinese learners in France has increased by leaps and bounds since 2000. In 1999, 111 French middle schools offered Chinese classes. In 2005 the number increased to 208, and soared to 362 in 2007. Today, 600 middle schools are offering Chinese courses, making Chinese the first language ever to enjoy such rapidly increasing attention in foreign-language education in France. Surpassing Portuguese, Hebrew and Arabic, Chinese has risen to fifth place as the foreign language most used in France.

However, it was not always smooth incorporating Chinese language into the French education system. Joel recalls that, at first most people did not expect the fad for the Chinese language to last long. Therefore, although French people actually became interested in Chinese language and culture two centuries before, it was not until 2006 that the French Ministry of Education created the post of Inspecteur général de Chinois, in response to the ever-growing international craze for the Chinese language.

Before taking up the post of Inspecteur Général de Chinois, Joel was an official on Chinese teaching in Frances Ministry of Education, and made extensive contributions to Chinese teaching. He designed the Chinese instructional program, formulating a specific framework for Chinese teaching in France. Moreover, he worked hard to integrate his valuable teaching experience into this framework. His efforts are one of the reasons France is able to keep its lead in Europe in Chinese teaching.

According to Jo?l, Chinese teaching in France still has a long way to go. Unlike in Asia, where Chinese has become an international language, in Westerners eyes the square-block characters are still mysterious and hard to learn. Whats more, Jo?l feels that the challenges presented by the growing demand for Chinese learning require the recruitment of more qualifi ed teachers and the revitalization of Chinese textbooks. On the whole, Jo?l thinks Chinese teaching is still in its primary stage in France.

Thirty years ago, Chinese was distant and mysterious for students in France like a language from the moon, and learning it seemed to have no career prospects at all. But now it is no longer as distant as the moon, and is rapidly popularized. Jo?l believes Chinese language learning has a bright future in France, and he often says: “You will defi nitely come into contact with China in the future.” In France, Chinese language and culture transmission is like a satellite moving fast on the right track and constantly speeding up.