完美故乡巴克汉诺

by Jayne Anne Phillips

For me, “hometown” refers to a small town, home to generations of family, a place whose history is interspersed with family stories and myths. Buckhannon was a town of 6,500 or so then, nestled in the foothills of the Allegheny Mountains of north-central West Virginia.

I left for college, but went “home” for years to see my divorced parents, and then to visit their graves in the rolling cemetery that splays its green acreage on either side of the winding road where my father taught me to drive. I know now that I loved Buckhannon, that its long history and layers of stories made it the perfect birthplace for a writer. My mother had grown up there, as had most of her friends, and their mothers before them. People stayed in Buckhannon all their lives. Despite the sometimes doubtful economy, no one wanted to leave, or so it seemed to me as a child.

Buckhannon was beautiful. Main Street was thriving. Local people owned the stores and restaurants. We lived out on a rural road in a ranch-style brick house my father had built. My father went to town early on Sundays to buy the 2)Charleston Gazette at the Acme Bookstore on Main Street. The Acme smelled of 3)sawdust, where Id replenish armloads of borrowed books under my mothers watchful eye. Shed finished college, studying at night while her children slept, and taught first grade in the same school her children attended.

I looked out the windows of Academy Primary School and saw, across South Kanawha Street, the large house in which my mother had lived until she married my father. My mother had graduated from high school in 1943, and my father, nearly a generation earlier, in 1928, but he wasnt a true native. Born in neighboring Randolph County, he was raised by three 4)doting 5)paternal aunts. Each took him into their families for a few years, and hed moved to Buckhannon for high school, winning the 6)elocution contest and giving a speech at graduation. This fact always amazed me. My father, 7)masculine in bearing and gesture, was not a talker.

Women in Buckhannon told stories, and men were defined by their jobs. He attended the local college for a semester, then went to work, building roads, learning construction. His first name was Russell; for years, he owned a concrete company: Russ Concrete. My brothers and I rode to school past 8)bus shelters 9)emblazoned with the name. We seemed to have lived in Buckhannon forever.

The town was truly a rural paradise; even into the 1920s, some 2,000 farms, averaging 87 acres each, surrounded Buckhannon. Such small, nearly self-sufficient farms survived through the Depression and two world wars. Miners and farmers kept Main Street alive, and the town rituals, seasonal and dependable, provided a world. Everyone knew everyone, and everyones story was known.

My father would be cooking fried potatoes in the kitchen, “starting supper,” the only domestic chore he ever performed. I knew hed learned to peel potatoes in the Army, cutting their peels in one continuous 10)spiral motion.

My dad, who was past 30 when he enlisted, served as an Army engineer and built airstrips in New Guinea throughout World War II, foreman to crews of G.I.s and Papuan natives. He came back to Buckhannon after the war and met my mother at a 11)Veterans of Foreign Wars dance in 1948. During the war shed trained as a nurse in Washington, D.C. The big city was exciting, she told me, but the food was so bad all the girls took up smoking to cut their appetites. A family illness forced her return; she came home to nurse her mother. My grandmother was still well enough that my mother went out Saturday nights; she wore red lipstick and her dark hair in a 12)chignon. My father looked at her across the dance floor of the VFW hall and told a friend, “Im going to marry that girl.” He was 38; she, 23.

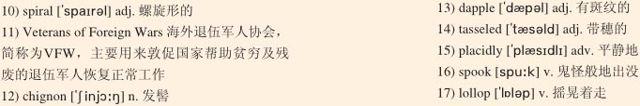

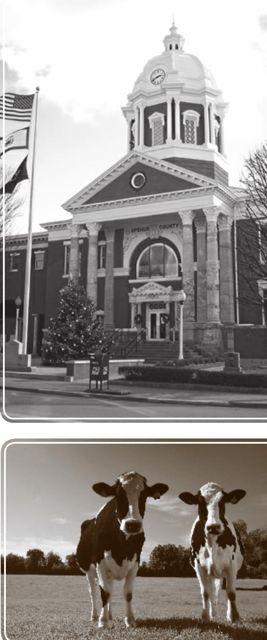

Hometowns are full of stories and memories rinsed with color. The dome of the courthouse in Buckhannon glowed gold, and Kanawha Hill was lined with tall trees whose dense, leafy branches met over the street. The branches lifted as cars passed, 13)dappling sunlight or showering snow. Open fields bordered our house. 14)Tasseled corn filled them in summer. Cows grazing the high-banked meadow across the road gazed over at us 15)placidly. They sometimes 16)spooked and took off like clumsy girls, rolling their eyes and 17)lolloping out of sight. Telephone numbers were three digits; ours was 788. The fields are gone now, but the number stays in my mind. Towns change; they grow or diminish, but hometowns remain as we left them. Later, they appear, brilliant with sounds and smells, intense, suspended images moving in time. We close our eyes and make them real.

对我而言,“家乡”就是那个小镇,那个一家几代人生活的故乡,其历史缀满了家族的故事和神话。巴克汉诺坐落于西弗吉尼亚中北部的阿勒格尼山麓,镇上大约有6500人。

我离开家乡去上大学,多年来,经常会回“家”探望离异的双亲,后来就是去到地势绵延起伏的墓园,探视他们的陵墓。将绿意盎然的墓园一分为二的是一条蜿蜒道路,就是在这条路上,父亲教会我如何开车。如今,我知道自己深爱着巴克汉诺,其悠久的历史和丰富的故事对于一位作家来说,简直是再完美不过的故乡。我母亲就是在这里长大,这和她大多数的朋友一样,而他们的母亲亦是如此。人们选择在巴克汉诺度过一生。即使有时候经济状况摇摆不定,也没人愿意背井离乡,或许这只是我作为一个小孩的见解。

巴克汉诺是个美丽小镇。镇上的主干道十分繁荣,商店和餐馆均由当地人经营。我们住在郊区公路旁一座农庄式的砖房里,房子是我父亲自己建造的。父亲每周日一大早就去主干道上的阿珂姆书店买《查尔斯顿邮报》。书店里满是木屑的香味,就是在这里,我常常会在母亲警觉的目光下借上一满怀的书。她完成了大学学业,当孩子们都入睡之后,她才开始秉烛夜读,同时她还在我们念书的学校教授一年级的课程。