实践研究:未来框架

作者:M·艾伦·戴明

“若没有考虑到景观解决方案,则无法通过任何措施实现可持续发展——零碳、零废物、净零水、生物多样性和适居性。通过公司的实践型研究和创新设计过程,DesignWorkshop已成为景观绩效领域的先驱。针对特定绩效目标设定成功目标以及测定方法,DW使我们增长知识,并生成关于景观解决方案在实现可持续发展过程中所起关键作用的证据。”

–景观建筑基金会执行董事芭芭拉·多依奇

景观建筑业是一个相对年轻的领域。景观建筑学的第一个专业研究课程建立于1990年(哈佛大学),但建立以来,大部分时间里景观建筑是否与学术相悖,这点一直有争议。数十年来,我们听到从业者抱怨说专业学者开展的研究并不能够满足设计行业的需求。在本论文中,我希望可以推翻这种抱怨:在像景观建筑业这样的知识型行业,从业者为什么不自己开展研究呢?毕竟看上去景观建筑师不是不知道该如何开展研究。那么是什么在阻止我们前进的步伐呢?

自20世纪90年代初,景观建筑师就已得知专业学者或混合从业者创作的文献作品不断增多,其中大部分都有助于设计行业知识性问题的分析,但对实践性问题帮助不大。从公平的角度来说,这些作者与其实践者同行服务的优先级不同。与营利性设计与开发行业相同,受更高教育的行业也制定了自己的规则并创造了自己的迫切需求。因此,我们发现,在某些机构中,理论与研究并非达到目的的手段,而是他们自身就是目的;在某些私营实践中,竞争等同于生存,导致他们不情愿分享学习经验,也不情愿腾出时间发展智力。

在过去10年左右的时间里,全球各大院校的新兴专业课程飞速发展,尤其是在中国,更是出现了新的、令人兴奋的、自由的、有时具有竞争性的议题与前景。学科研究的范围越来越广泛。虽然与任何学科的正常演变相兼容,但是,对于想要解决特定场所有关问题和方法的人而言,这种不确定性是令人困惑甚至沮丧的。

幸运的是,在DesignWorkshop实践的内容和结构下(见《世界建筑导报》的专题),我们可以看到,景观建筑业的专业学者与其它专业人士之间的可见“意见分歧”开始出现弥合的迹象。面对复杂的挑战,许多景观从业者开始认识到,必须有更集中、更具识别性的研究议程,才能在工作中立于不败之地,有效提升该领域的价值,并对环境产生积极的影响。我的观点是,实践者与专业学者应该相互合作,结成强有力的联盟以增长共享的知识,而不是在我们自己的圈子里相互竞争。简言之,为了设计行业的成功,为了从“好变成极好”,景观实践者和景观专业学者都不能无视对方的努力——当然,我们必须找到学习方法,更重要的是,相互学习。

开创性实践研究:记录成功与失败

在努力收集和组织各个实践领域共享的“显性”知识的过程中,有一段富有成效合作的悠久历史。1982年,景观建筑教育者理事会(CELA)创建了第一份景观建筑同行评议杂志《景观期刊》,并在这份杂志上宣传“与景观设计、规划和管理有关的研究和学者调查结果”。30年后,有六份英文版同行评议研究杂志专门为景观建筑业服务,还有其它数百份杂志广泛地丰富了该领域。与CELA和《景观期刊》一起,美国景观建筑师协会(ASLA)及其州立分会长期以来维持着各项专业和学生研究的奖励认证,这些都能“促进该领域的知识体系”。其它国家目前采用的也是类似的方法。

就在过去的10年里,景观建筑基金会(LAF)建立了一种综合、系统的方法来记录该领域的成功、创新性案例研究,从而又向前迈进了一步。马克·弗朗西斯的“景观建筑案例研究方法”(2001年)出版在《景观期刊》上,在此基础上就建立了LAF案例研究倡议。随后,LAF还举办了“土地与社区设计案例研究系列”活动,弗朗西斯的《村庄家园:设计社区》(2003年)在该系列竞争中取得第一名。随着时间的流逝,出版一系列印刷专题论文的巨大经济费用让人咋舌,但是,出现了一种更机敏的创新理念——在线获取案例研究摘要,使学生、设计师、业主和开发商等均可很容易地获取一些数据。为了使这些案例研究得到更清晰的关注,景观绩效系列方法(LPS)明确识别出可持续性特征的项目。自开展景观绩效初步研究以来,已收集到70多个项目的数据,这使得数据库的容量急速增长。

DesignWorkshop积极参与其实践成功与失败的记录,至今已有10个项目被纳入LAFLPS计划(有七个已出版)。正如本期的《世界建筑导报》所展示的,DesignWorkshop创新地运用新知识在许多方面都有好处,其中也使其潜在的竞争对手获益。项目的经验教训有助于其他设计师提升视觉质量,对社区产生积极的社会影响,提供有弹性的生态服务,甚至有助于传授关于成功商业模式的经验。这也提出了一个实践研究的关键问题:对令人日益担忧的由新知识产生的知识产权、版权和竞争优势,如何应对?

?

许多从业者认为,从项目设计、原材料、决策过程或者建造与安装的成败获得的知识属于私人所有,是他们向客户提供的服务所附带的。如果此类知识有助于从业者精通专业知识,则通常属于“隐性”或个人知识。同样地,对于研究型大学和分析型行业所产生的知识产权的分配问题,其管理规则已成为免费信息优化分享的关键。许多机构和政府补助政策限制了新知识的传播,即使是学术带头人也不例外。

不过,通过公平使用条款、开放来源软件和“免费软件”等方式,信息科学和数字创新的另类思维开创了分享公共领域理念的新方法。还有一项日益兴起的运动,认为“新知识”必然有利于实践,所以应该成为专业能力建设的重要和必需形式。像DesignWorkshop这样先进的机构和公司,与研发行业的工程师或开展临床试验的医生相比,似乎是“实践研究”最积极的拥护者。DesignWorkshop的领导层把这种实践视为一项专业挑战,也把其积极地视为企业发展的机遇。如果其他受尊敬的专业机构也有研发的惯例,并且想尽办法把研究活动和其它知识构建形式纳入其商业计划和成本结构,那么,为什么设计行业不这样做呢?为什么景观建筑师不能倡导这样的努力呢?

可持续发展与价值观

正如大家熟知的,通常根据“3个E”,经济(Economic)效益、环境(Environmental)效益和公平(Equitable)社会效益来衡量该项目是否遵循可持续发展理论,这三项也被视为可持续规划设计的基石。目前,有些实践者和学者主张拓宽可持续性的定义,把其它不容易衡量的效益也包括在内。例如,2010年11月,景观建筑师注册管理局(CLARB)进行了一项内容分析,来探索景观建筑的法规授权,以保障并促进公众健康、安全和福祉。在检验“福祉”一词更深层含义的研究中,通过许可检验和专业实践,CLARB意欲对一种衡量能力的替代方式进行评估,这种能力就是理解和保护无形的“优秀设计”。他们发现,福祉的概念与幸福安康的概念(表现为欢乐、健康、自豪、场所关联和繁荣兴旺)的关系非常密切,几乎是不可分割的,因此它是景观和其它设计时表达情感可持续性的重要部分,许多人都将其视为可持续发展的第四个基石。但是,在景观设计中应该如何开展衡量其欢乐、美丽抑或是场所关联性的份额呢?(参看图1和图2)

城市土地学会出版的《城市设计与盈余》(2008年)首次开创了这种思路,它开发了一种宽泛矩阵,作者称之为“四重盈余”。在检验包括“感性回归”在内的城市价值观的过程中,作者认为,对场所营造的审美和情感回应是以“有影响力的支持者”为导向的,可通过其它非数字的社会和财政投资回报的红利进行衡量,包括优秀设计:“新设计支持者关注的是城市生活的质量、环境与文化的敏感性、可持续发展和观赏价值。”此范例表明,通过合作和分享其在每个项目学得的经验,景观建筑师不仅可以帮助社区实现环境的可持续发展;还可以使其通过竞争保有社会资本和智力资本,使社区繁荣昌盛。

高质量的研究才能建立有说服力、有依据的并支持设计带来多重价值的证据。如果我们的价值指引着一切我们所做的和所创造的,那么我们所学到的和所了解的--例如,我们景观建筑的专业知识--将会在根本上与其他行业有所不同。西蒙·史沃斐曾针对这一主题做过决定性的论述:“设计创造了‘可能性的空间’(德·兰达和埃里森,2008年)……通过设计和管理可以塑造合意的、可行的未来,并通过科学评估予以检验。”因此,把开放式的设计价值观与封闭式的研究和评估过程相结合,景观建筑师必须能够自如地协调好这两者的关系。可量化的数据仍然是呈现在开发商、投资商和决策者面前的最具说服力的证据形式,这些人中的大部分仍然控制着全球的设计与开发议程。不过,任何想要建立全面健全的新知识与理解体系的成功行为,应该也能够接受由景观实践(包括设计研究)产生的各项研究的多种价值、形式和定义。

设计与可归纳的知识

越来越多来自该领域的证据(ASLA、LAF、英特网等)证明,景观建筑行业实践整合了许多形式的研究。我们认为,在设计企业以及专业建设领域早已出现了各种研究策略,从仅为了解决某个特殊问题而组建的各个团队到在设计企业任命研究总监,他负责评估和组织建成项目的可衡量效益。这种新的弹性恰恰是景观建筑领域实现其跨案比较的潜在能力所需的。(参看图3)

为了更好地理解现有实践研究的形式和范围,我和同事们已开展一项探索性调研,深入了解专业人士对开展研究调查的态度。我们还力求检验和阐述《景观建筑研究:调查、策略、设计》(2011年)首次引入的综合性框架,这本书阐述了在景观建筑中出现的实践研究的多项策略(表1)。特别值得注意的是,我们的调研要求实践者将其典型的专业服务和调查与普遍接受的“研究”的定义相联系起来(“研究”的普遍公认定义以联邦法规为基础,被合作机构培训学会所采纳),每一个部分都是标准的、有弹性的:“系统研究包括研发、检验和评估,旨在发展或促成可归纳的知识。”虽然具有高度的通用性,但是我们仍然认为,该定义对描述领域和专业机构可能开展的实践范围非常实用。该定义包含了每项实践采用的各种策略和方法,从实验到研究型设计、从参与性设计过程到历史性阐述、从直截了当的描述性案例研究到动态建模,等等。

我们的调研收到的一些早期回应表明,有些实践者抵触可归纳性的概念,仿佛在追求敏感设计的过程中,获得更多专业知识是不可能的或站不住脚的。但是,为什么优秀的设计师不从特定场所的或基于项目的与其它场所和环境有关的调查中获取支配性的见解?是的,按服务收费的、仅为一次性的为解决问题而建立的研究与为获得知识价值而发起的原始的、可归纳的研究之间的智力价值存在着明显的区别。但研究实践无须受这种非黑即白的观点的局限。在解决以客户为导向的问题的过程中,如果项目信息被系统地收集、组织成数据集,并按照理论上已知的问题进行严谨的分析,那么,实践与研究之间固定的传统界限很快就会模糊。因此,我们针对实践研究开展的调研寻求的是以专业实践的典范来指引前进的道路——不仅使研究变成一种承诺,而且使研究变成一个“品牌”;不仅是一种商业模式,而且是一种倡导类型。

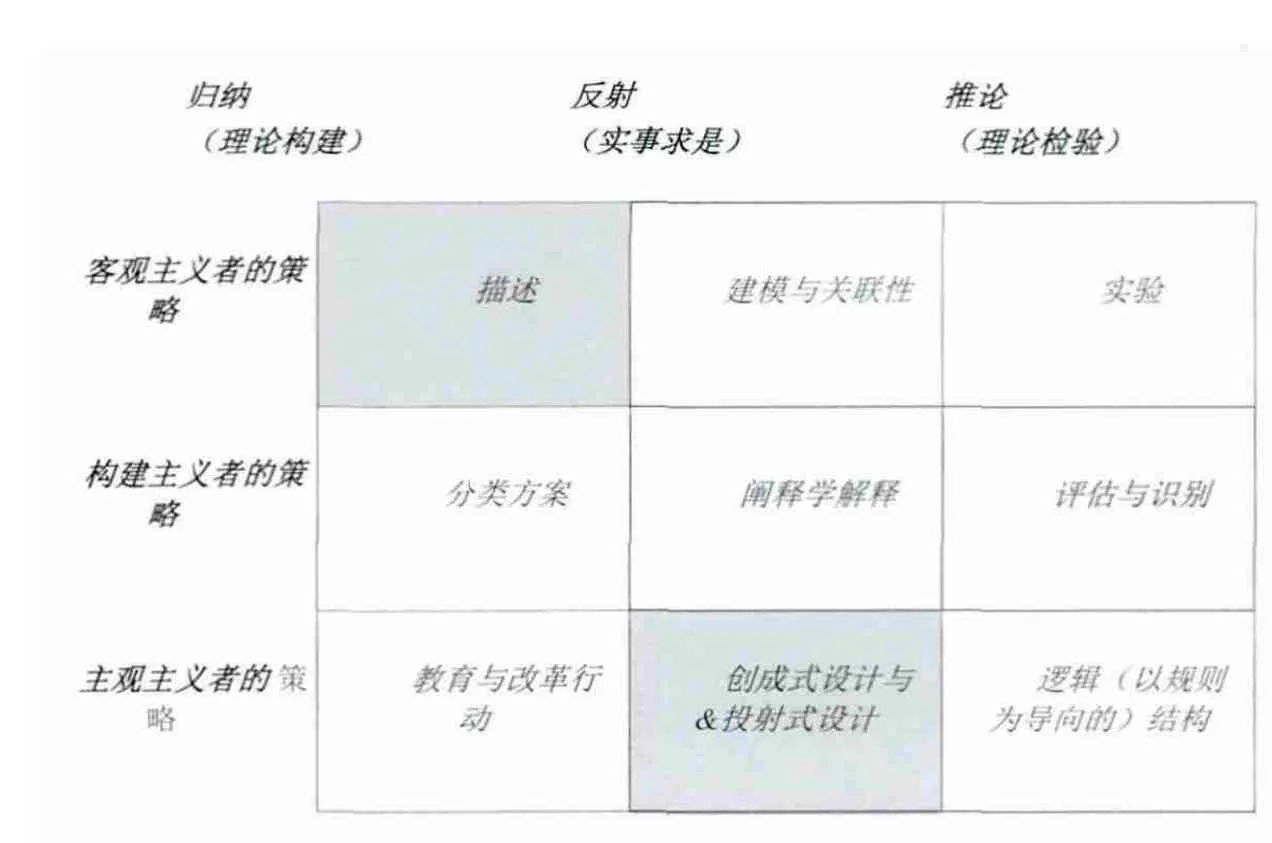

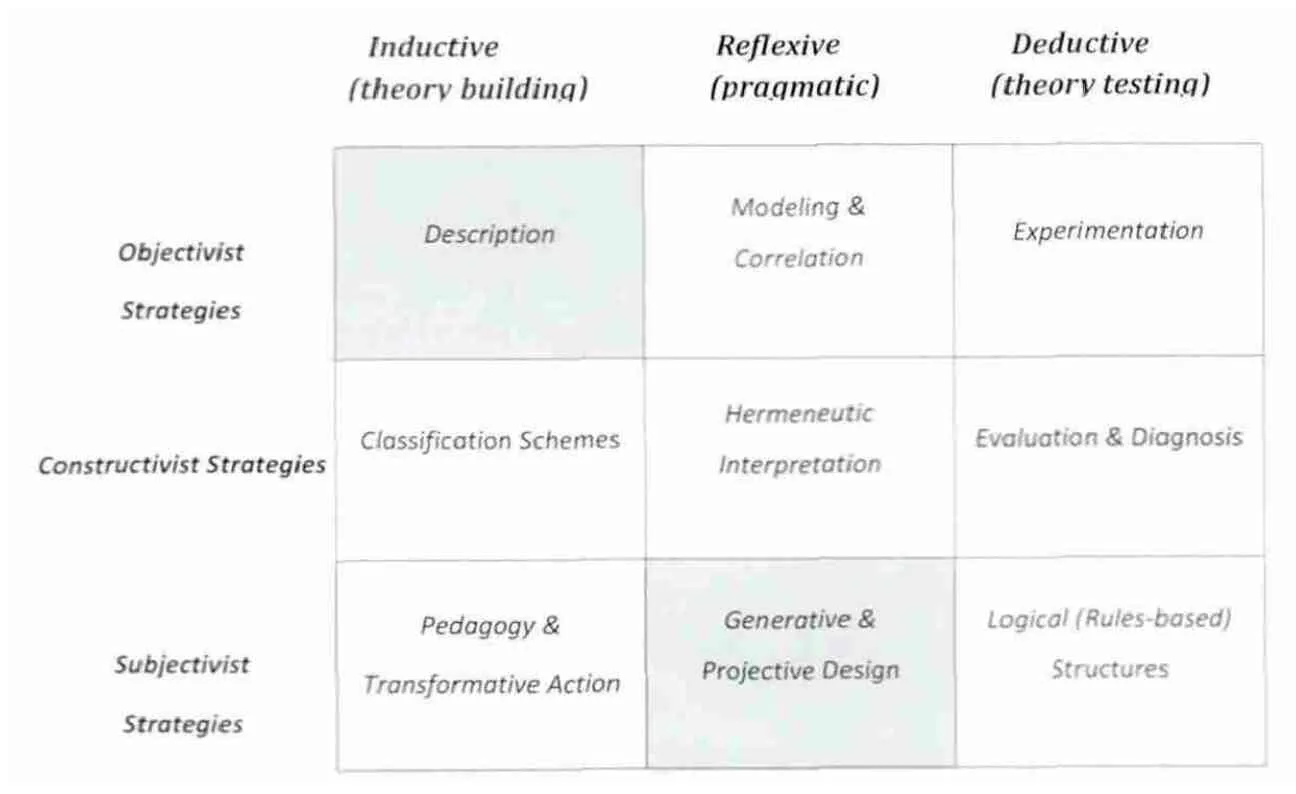

表1 :景观建筑的研究策略:实践框架(改编自戴明和史沃斐的作品,2011年)

作为在我们即将开展的研究中提及的专业模范之一,DesignWorkshop在其追求更广大的专业研究议程中并不孤单;然而在专业实践如何从学术界再获取知识并使研究论述焕然一新方面,该公司的项目已跻身行业最佳典范。DesignWorkshop的作品如何适应我们庞大的框架?在表1明确的九大基础研究策略中,DesignWorkshop至少参与了两项可归纳实践知识的策略:

描述性策略包括对可比较的和纵向的案例研究进行的准备工作。对新场地和/或实践的客观汇报和描述正好属于案例研究。例如,通过参与本期的《世界建筑导报》以及LAF案例研究之景观绩效系列,DesignWorkshop所收集、组织和提交的案例研究数据有助于成败模式的共同理解,而成败模式是较大型的问题构建与调查的根本。通过真诚、客观地检验工作的成败,在更长的时限内新知识可能更有充分的理由和概念性,而且,仅仅通过定义就可以将新的社会和环境变量纳入其中。

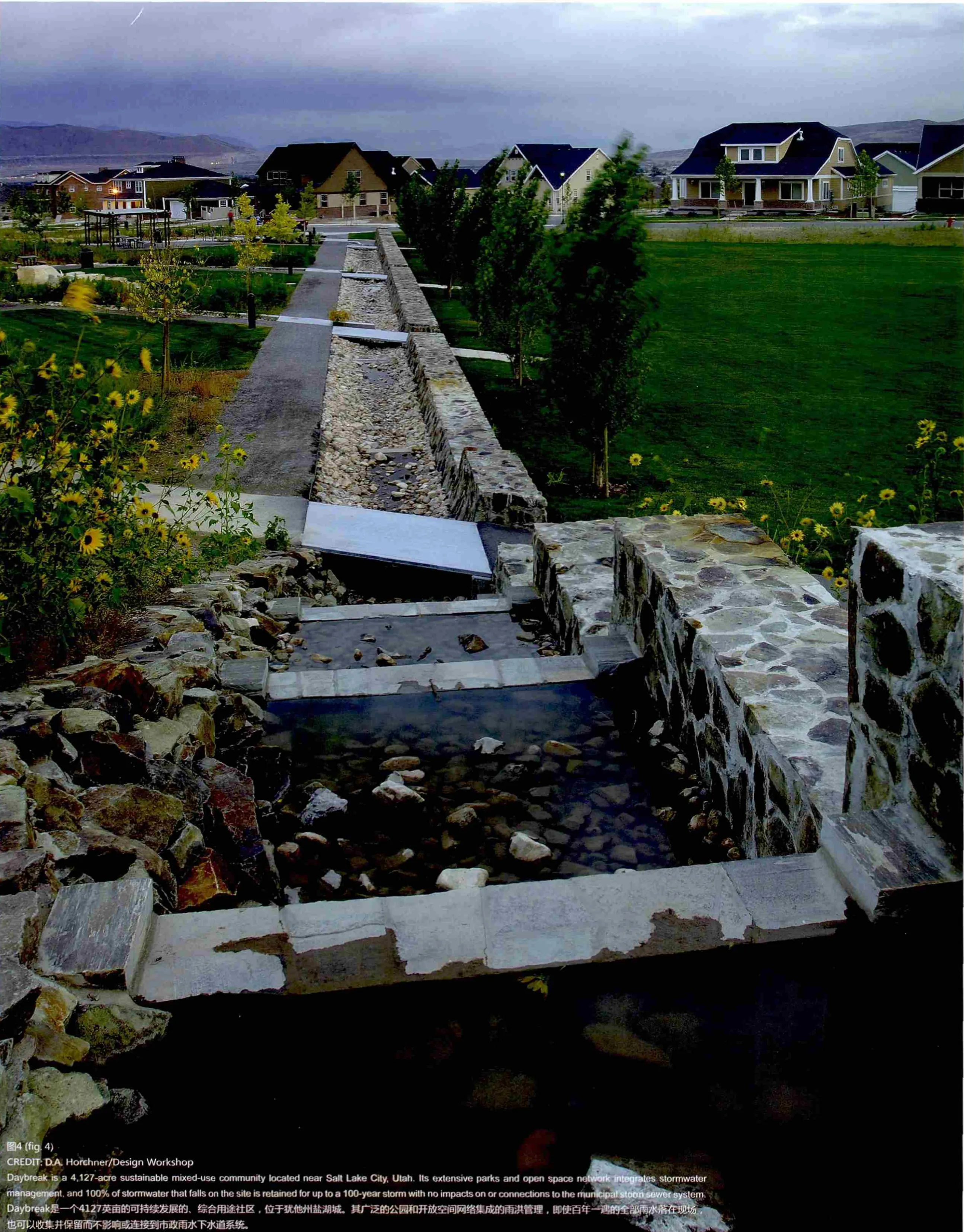

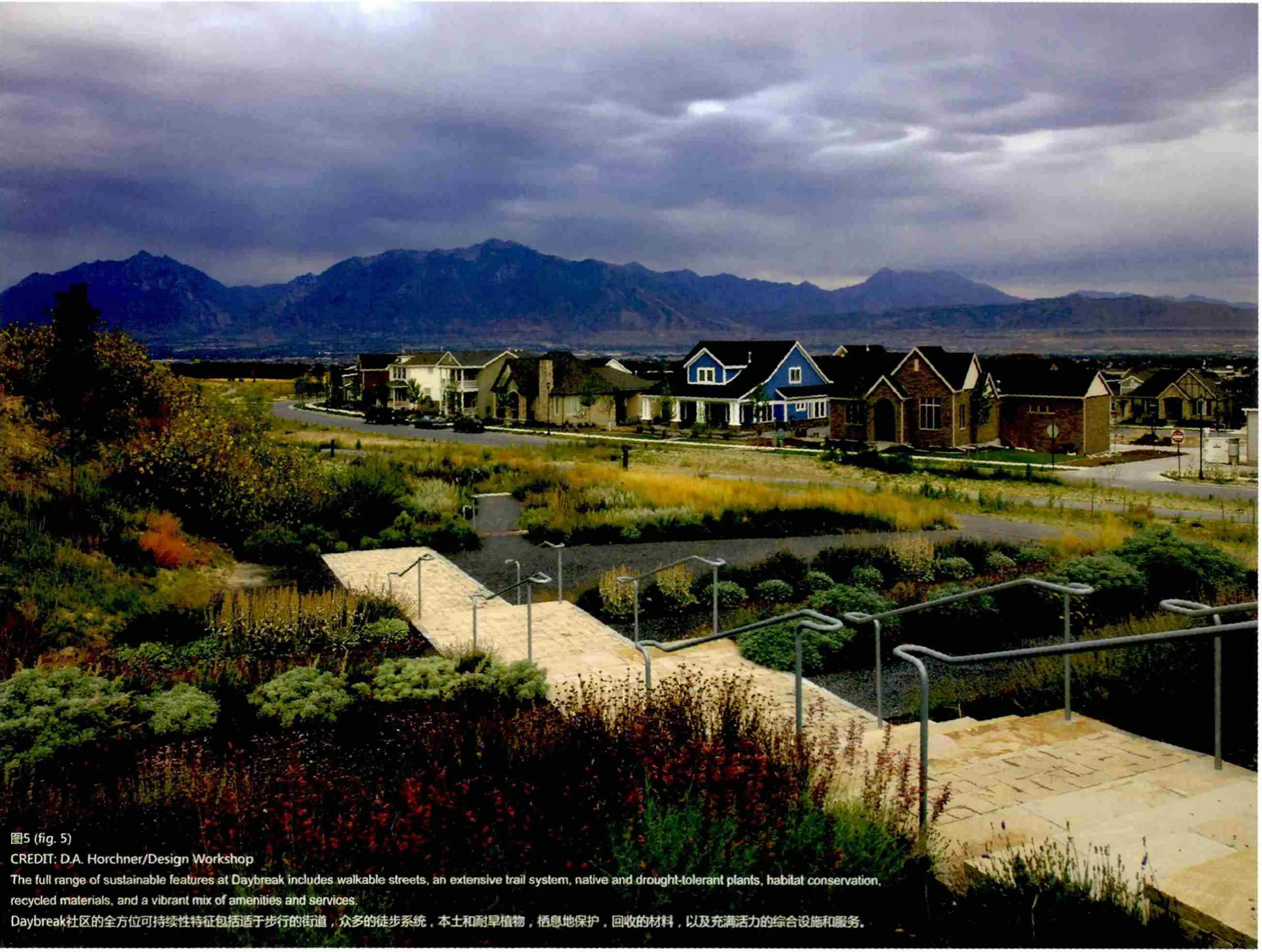

投射式设计策略包括有时被称为设计型研究的策略。通过设计以重新提出现有问题或通过创新以提出新的学科问题,投射出理论原则或主张,使设计过程被激活而成为一项研究策略。是的,跟医学一样,将提供服务所得利益与生成新知识所得利益划分清楚,这有着令人信服的道德理由。不过,在一些实例中,设计研究可以达成多种目的,尤其是在客户分享项目目标的情况下。(参看图4、图5)若在理论议程中使用投射式设计(例如:当以可持续发展和/或社会公平理论来对开发“完整的街道”做出建议时),很可能会发生以下几种情况:(1)出现一种新的生成式过程理论(设计理论);(2)应用/检验衍生式理论以改善新的场所、图像、现象、关系和影响的生成(设计中的应用研究/通过设计的应用研究);(3)在观察生成的作品过程中出现的实据理论(循证设计)。因此,作为研究的设计的变化对新的学科知识大有帮助。一些常见的排列,如:形式和类型学/比较分析,更确切地说,属于分类和解释策略。但是,在所有的情况都需要服从一个重要的警告:只有严谨地汇报项目成败的目的、程序和结果并予以公正的评估(即,无任何偏见,也无固有的“利益”),这个设计才可称之为研究。

当然,微观研究过程提出了几乎所有的设计问题:必须按特定模型建造和评估场地系统;必须计算成本和计划面积等等。不过,如果获得的知识不能归纳和共享,则不能称其为研究。这可能会引起混淆。设计师在讲述场地或有关场地的信息时,可以采用阐释学解释的非研究型推论;了解人工因素和索引痕迹可以丰富和指导特定场所设计,其中包括材料和空间次序的选择。评估与识别的非研究型推论可用于每一种场地的分析中,例如:判断施工土壤的质量和深度,或者判断场内或场外某些视线是否满意。每当设计团队针对校区或公园的方案设计或规划举办公开听证会或得出反馈意见时,就会激活参与行动的非研究型推论。不过,无论它多么宝贵,大部分特定场地推论活动都不能也无法满足广泛研究议程的要求。

新知识与把关文化

在当今的景观建筑行业,大多数正在开展的杰出的实践型研究都来自于私营企业与公共机构之间的新型伙伴关系以及与之相互合作的学术界。即使是资金不足的情况也应支持此类成果卓著的联合研究。强调重新产生的对研究兴趣的重要性存在于以下两个方面:第一,知识分子会更容易与企业合作,分享研究方面的问题,既符合专利所有权的切入点,也符合学术研究/同行评议的切入点;第二,更多关于健康、安全和福祉的问题,包括气候变化、资源管理、社会公平与公共卫生以及该领域的法规合法性等,很快就会推动专业活动的发展,甚至占据主导地位。

我们还有一些观念冲突需要克服——尤其是关于同行评议和资格认证的观念,这两者都是上个世纪的遗留实践,对学术界产生了重大的影响。原则上,两者都是必要的实践,它是在专业和学术环境中,通过自我管理的共同过程来保护知识的完备性。但是,无可否认,实践者投身的这些程序有时反复无常、浪费时间而且经常使人筋疲力尽,很难想象要是将其强加在研究者身上的会是怎样?因此,学术研究同行评议模式的古老传统涉及到一种风险等级,尤其是对年轻的从业者和学者而言,他们往往无法承受得起这样的风险,也无法避免。在当代传媒界和学术资金循环快速发展的情况下,旧的同行评议模式正在瓦解,因为它仅仅是花很长的时间去查看已出版的甚至是在线的高质量作品。如果研究者的目标是对实践产生影响,而与学术信誉或学术声望截然相反,那么,这些同行评议方式可能会被视为令人沮丧的障碍。

新一代的学者,尤其是有雄心使设计与研究议程相结合的学者,通过其批判性和评论性的不同议程,选择将他们的工作面向另类的领域和读者。由于研究和创造性调查都可以采用许多不同的方式进行,因此,同行评议也可以。一些主要的研究型大学现在开始接受,同行读者采用的许多评论、评估和赞誉方式足以说明研究与创新素质的基本原理,其中包括内外部的有效性、公正性、适用性、可靠性、独创性和经济性。

考虑到这些新兴的实践,那么实践型研究的同行评议过程或与之等同的过程可以采用什么方式呢?这无疑取决于工作的格式与内容。一些期刊(包括已出版的和在线期刊)大幅度地缩短或改变传统的同行评议过程,或者完全绕过这个过程来支持编辑部、委员会或者更加非正式的维基类型的、连续自发型的、共识型评议过程(如:维基百科)。设计竞争与获奖计划往往是由某个特定事件评判委员会进行评议的,该评判委员会是根据其经验和批判性洞察力挑选出来的,审议往往是在集中的期限内进行。资金和奖学金申请以及作品展示的挑选方式往往也与之类似。

合作,尤其是与老客户和/或可信的项目专员合作,是观察同行接待的其它方式。建成工程、本文提及的工作室或者已出版的和/或颇受公认的文化分析家好评的设计规划也可被视为同行评议的方式。鉴于所有这一切,尽管该领域的专业人士仍未在研究定义、逻辑、目的和效益方面达成强烈的共识,专业的“把关”文化仍可能会继续慢慢从内到外地改变学术领域。

研究:全球事业

专业研究的作者目前包括每一个人——私营设计企业的景观从业者、跨学科公司或企业咨询公司、非营利性公司、国营企业机构以及混合学术研究的实践者。生产和消费研究的速度正在加快;有些人甚至已预言,实践型研究将挑战传统的同行评议发表过程,刊物的更新速度太慢且关联性弱。大多数有修养的实践者都是有技能的跨学科合作者,他们对学术知识的“筒仓”缺乏耐心。学生们希望看到他们正在学习的研究技巧和方法如何转化为专业应用,而最理想地是转化为专业的聘用,这对景观建筑学校的专业课程的框架/重点产生重大的影响。所有这一切均表明,对比传统期刊目前能够应对的速度,新知识的共享和应用必须要快得多;同时,确保严谨地审核新的理念与实践,并谨慎对待未加思索的方法产生的意外后果符合该行业的利益要求。

由于实践者对实践研究担负有更大的责任,人们就很容易会猜想,该领域的研究议程开始发生改变,也许是接受授权以达到更佳的效应,同时也更多地关注于知识的形成,以便实现预期的社会和环境效益。虽然这可能会导致使用更多理性的手段,但是,也会将焦点转向认知我们共享的价值观——有些人称之为价值理性。毕竟,大部分景观建筑师还是会分享某些共同的目标的,如:创建或维护优美而健康的场所,构建知识,掌握技术知识、预测性知识、概念性知识和伦理知识,确保持续的集体进步,服务社会。这一套核心价值观给我们带来了希望,希望早期采用实践研究方法的人将带来更佳的设计、产生更重大的专业影响,从而对景观设计师与规划师们能够和应该了解的东西产生更高的期望。

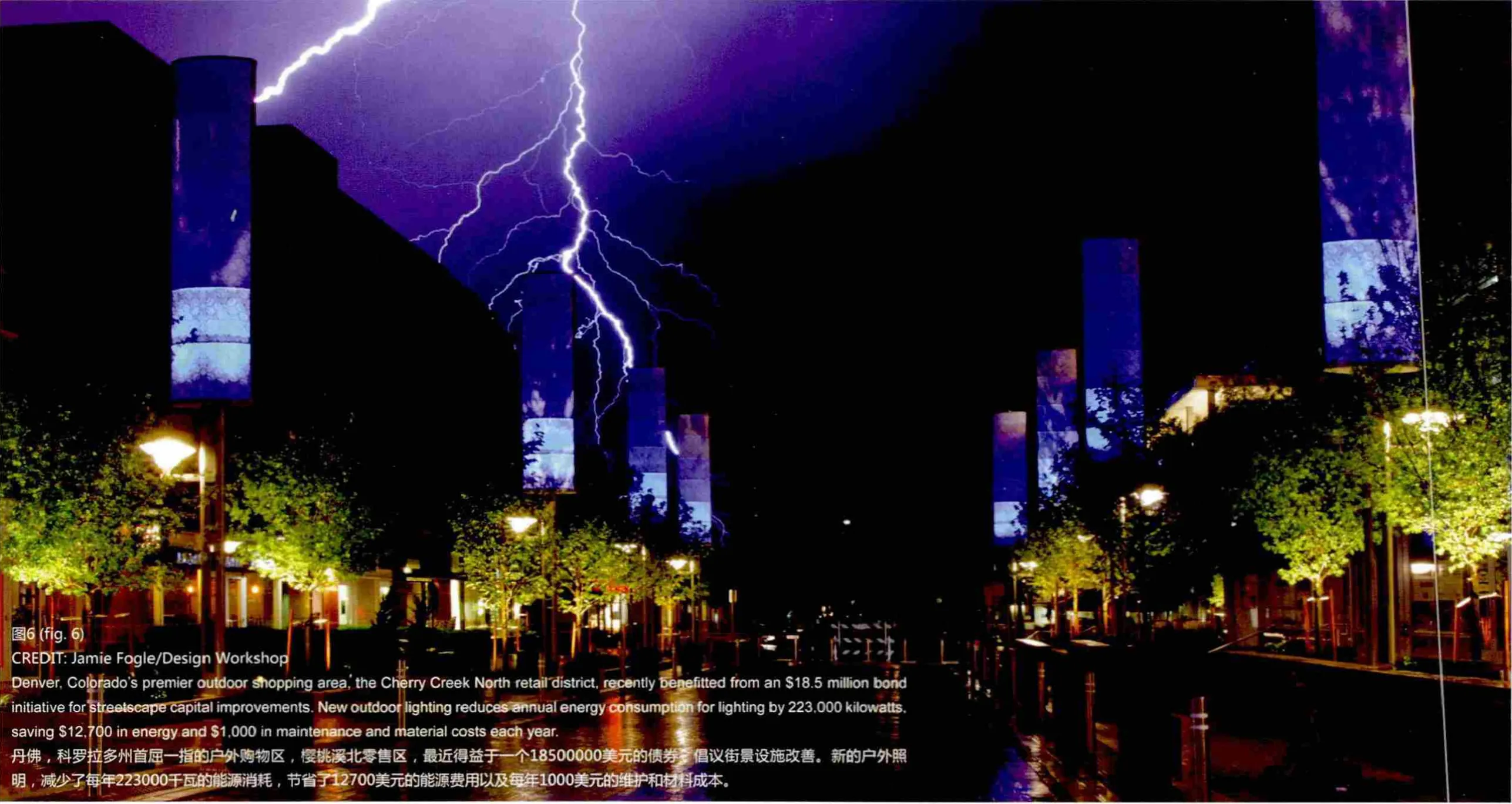

原则上,我们构建的理念影响范围应该仅仅是巩固全球的景观建筑事业。这一项全球事业的传播是通过倡导、专业组织的兴起、最佳实践的标准和规范、会议、专业课程、指导以及跨学科和跨国合作等来实现的。中国景观建筑师协会(CSLA)正在这个极其重要的国家快速推动该行业的发展,并正在致力于开发一个系统来认证其颇具影响力的学校网。国际景观建筑师联合会(IFLA)在提升非洲、南美洲和其它区域的景观建筑专业地位方面取得了重大的进展。景观建筑教育者理事会(CELA)正在倡导和指导墨西哥、中美洲、南美洲和泛太平洋/南亚的专业学者巩固景观建筑专业教育计划的标准。不过实际上,当行业内的成员未能如我们行业提倡的那样,以相同的远见和尺度范围生成和分享其知识时,全球的景观建筑事业实际上是被弱化了。(参看图6)

意识到景观建筑业是全球市场一股较小的专业力量,这也许可能会说服我们重新思考知识生成在开发该行业的总体“竞争优势”方面所起的作用。在这个创新的时代,若对扩展学科的知识库无所贡献,任何企业都无法维持其竞争优势。正如库尔特·卡伯特森在本期前面部分所提及的那样,人才和培训都有助于保持此类竞争优势,各企业可以通过公司范围内的示范性项目工程以及更为广泛的学科专业知识证明这一点。目前的关注点是综合开发一个证据库,“证明”景观建筑的价值、效益和影响,以表明知识形成对维持整个行业的竞争性是何等的重要。

当单个公司竞标某项工程时,他们会对客户隐瞒其专业服务和实践专业知识,直至签约成功。然而,其它可能更大型的应用设计和工程行业则乐于声称其拥有类似的专业知识。这是真实的竞技场,充满了新知识和新影响的跨学科竞争。通过分享一般和特殊的学科知识,所有景观建筑师都可以帮助彼此(也包括他们自己)提升行业能力来尽可能地在最大的尺度上竞争以获得最高的利益,保障重大的公共投资,并产生广泛的环境政策和影响。如果我们能够在新知识的竞技场上立于不败之地,我们也许可以最终看到景观建筑业在知识方面的不断成熟,并在全球的重要学科中找到其应有的位置。如果我们无法做到这一点,那么,我们该如何保护景观建筑业不被淘汰呢?

M·艾伦·戴明博士是伊利诺伊大学香槟分校的景观建筑学教授,讲授设计工作室、历史和理论以及研究设计课程。获得哈佛设计研究院设计博士学位以及艺术史、景观建筑和环境研究等学位。自2002年起,与詹姆斯·F·帕尔默一起担任《景观杂志》的主编,2006年至2009年,独自担任主编。她是景观建筑教育者理事会(CELA)的前任会长。与西蒙·史沃斐合著了《景观建筑研究:探究/策略/设计》(威利出版社,2011年),概况描述了当今景观建筑使用的数大研究策略。这是一本探讨从实践、公司和代理机构中涌现的调查研究的新作,并即将问世。

Landscape architecture is a relatively young f eld. With its f rst professional course of study established in 1900 (Harvard University), landscape architecture has been arguably anti-academic for much of its existence, and for decades, we have heard practitioners complain that research produced by academics does not serve the needs of the profession. In this essay, I’d like to turn the complaint on its head: in a knowledge-based profession like landscape architecture, why don’t practitioners also produce research? After all, it’s not as if landscape architects don’t know how. What is holding us back?

Since the early 1990s landscape architects have been able to point to a growing body of literature produced by academics or hybrid practitioners, most of it devoted to the analysis of intellectual problems in our discipline rather than practical problems in our profession. It is fair to point out that these authors typically serve a dif ferent set of priorities from those of their practitioner cousins. The industry of higher education writes its own rules and creates its own exigencies, just as the commercial industry of design and development does. Thus we f nd that in some institutions theory and research are not means to an end – they have become ends in themselves; in some private practices competition equates to survival, leading to a reluctance to share learning experiences or make time for intellectual growth.

In the past decade or so, the rapid development of new professional programs in universities around the world, especially in China, has led to the emergence of new ,exciting, liberating, and sometimes competing agendas and perspectives. Disciplinary research has become increasingly dif fuse. Although compatible with the normal evolution of any discipline, such indeterminacy may seem confusing, even frustrating,to those seeking def nite answers and solutions to site-specif c problems.

Fortunately, in the content and structure of Design W orkshop’s practice (featured in this special issue of Architectural Worlds), we see signs that the perceived “divide”between academics and other professionals in landscape architecture is starting to close. In the face of complex challenges, many landscape practitioners have begun to recognize that a more focused and identif able research agenda is needed to competesuccessfully for work, effectively advance the values of the f eld, and to make positive impacts in the environment. My argument is that, rather than competing amongst ourselves, practitioners and academics should be working together as powerful allies in the advancement of shared knowledge. In short, for our profession to succeed, to move from “good to great,” neither landscape practitioners nor landscape academics can afford to dismiss each other ’s efforts – rather, we must f nd ways to learn from,and more importantly, learn with each other.

图3 (fig.3)CREDIT:D.A.Horchner/DesignWorkshopAprojectteamiteratesadesignsolution.一个项目小组再三强调一种设计解决方案。

Pioneering Practical Research: Documenting Success and Failure

In the effort of collecting and organizing “explicit” knowledge shared in our various domains of practice, there is a long history of productive collaboration. In 1982 the Council of Educators in Landscape Architecture (CELA)established Landscape Journal, the premiere peer-reviewed journal in landscape architecture, and charged it with disseminating the “results of research and scholarly investigation relating to landscape design, planning and management.” Three decades later, a half-dozen(English-language)peer-reviewed research journals serve landscape architecture specif cally, with hundreds of others enriching the f eld in general. W orking together with CELA and Landscape Journal, the American Society of Landscape Architects(ASLA)and its state-chapter af filiates have long maintained awards programs recognizing professional as well as student research that “advances the body of knowledge” for the f eld. Similar approaches are now being adopted in other countries.

In just the past decade, the Landscape Architecture Foundation (LAF)has taken another step forward by establishing a comprehensive and systematic process for documenting successful and innovative case studies in our field. The LAF Case Study Initiative was established with the publication of Mark Francis’s “A Case Study Method for Landscape Architecture” (2001)in Landscape Journal.1Subsequently, LAF undertook the Land and Community Design Case Study Series, with Francis’s Village Homes: A Community by Design (2003)among the first titles in the series.2Over time the f nancial burden of publishing a series of print monographs faltered, but a more agile new idea emerged – case study digests available on-line, providing highly accessible data for everyone from students and designers to owners and developers.Bringing these case studies into clearer focus the Landscape Performance Series(LPS)specif cally identif es projects characterized by sustainability. Since the launch of the Landscape Performance pilot study, a swiftly growing dataset of 70+ projects has already been assembled.

With ten projects accepted into the LAF LPS program (seven published), Design Workshop has actively participated in the documentation of its practical successes and failures. And as this issue of Architectural Worlds demonstrates, Design Workshop’s innovative applications of new knowledge pays dividends in many ways,including benef ts to potential competitors. Project lessons may help other designers improve visual quality, make positive social impacts on community, provide resilient ecological services, and even impart lessons about successful business models.And that raises a pivotal issue for research in practice: how to manage growing concerns over intellectual property, copyright and the competitive edge provided by new knowledge.

?

Many practitioners believe that knowledge gained from the successes or failure of project design, materials, decision-making processes or fabrication and installation,is proprietary and incidental to the services they render to a client. If such knowledge contributes to professional mastery it is usually in a “tacit” or personal way . Similarly,the rules governing distribution of intellectual property generated within research universities and analytical industries has been a major sticking point for the optimal free sharing of information. Many institutional and government grants restrict the ways in which new knowledge may be disseminated even by principal investigators.

However, alternative thinking in information science and digital innovation is pioneering new ways of sharing ideas in the public domain through fair-use clauses,open-source software and “freeware,” just to mention a few. There is also a growing movement to acknowledge “new knowledge” as a corollary benefit to practice and therefore an important and necessary form of professional capacity-building.Progressive agencies and firms such as Design W orkshop seem to be the most aggressive proponents of the discourse of “practical research,” comparing their work to engineers in research and development industries or to medical doctors conducting clinical trials. The leadership of Design W orkshop recognizes this practice as a professional challenge and embraces it as an opportunity for corporate growth. If other respected professionals have institutionalized research and development, finding ways to build investigative activities and other forms of knowledge-building into their business plans and cost structures, then why not the design professions in general –and why shouldn't landscape architects pioneer these efforts?

Sustainability and Values

Projects adhering to theories of sustainability, as commonly understood, typically have been measured according to the “Three ‘E’s,” representing the range of economic, environmental and equitable social bene f ts considered the cornerstones of sustainable design and planning. Some practitioners and scholars now advocate for broader def nitions of sustainability that include additional, less-easily measured benef ts. For instance, in 2010-11 the Council of Landscape Architecture Registration Boards (CLARB)3undertook a content analysis exploring statutory mandates in landscape architecture to safeguard and promote health, safety and welfare. In research examining the deeper conceptual dimensions of the term “welfare,” CLARB intended to assess alternative ways of measuring competency in understanding and protecting the intangibles of ‘good design’ both during the licensing examination and in professional practice. They found that the concept of welfare was so closely linked as to be almost inseparable from notions of well-being (as in joy, health, pride,attachment to place and prosperity)and therefore was an important part of the affective sustainability of designed landscapes and other places, what many consider to be the fourth cornerstone of sustainability. But how does one begin to measure the quotient of joy, of beauty or perhaps place attachment, created in the designed landscape? (see f g. 1 and f g. 2)

A seminal work in this line of thinking, the Urban Land Institute’s publication Urban Design and the Bottom Line (2008)develops a broad matrix for what the authors call the ‘quadruple bottom line.’ In examining urban values that include “return on perception,” the authors argue that aesthetic and emotional responses to placemaking are guided by “influential constituencies,” and may be measured by other, nonnumerical dividends returned on social and financial investment, including good design: “New design constituencies focus on quality of urban life, environmental and cultural sensitivity, sustainability and visual value.”4This example suggests that,by working together and by sharing what they are learning on a project by project basis, landscape architects can help communities achieve more than environmental sustainability; they also help communities compete for retention of the social and intellectual capital that makes them f ourish.

High-quality research is needed to build persuasive, grounded arguments supporting the multiple values added by design. If what we value guides everything we do and make, then what we learn and know – i.e. our expertise in landscape architecture –will be fundamentally dif ferent from other professions. Simon Swaf field has written decisively on this subject: “design creates ‘possibility spaces’ (De Landa and Ellingsen 2008)… desirable and feasible futures [that]can be shaped through design and management, and tested through scienti f c evaluation.”5Thus combining the openended values of design with the close-ended processes of research and evaluation,landscape architects must be poised to negotiate both realms. Measureable data still present the most persuasive forms of evidence to developers, investors and policymakers who, for the most part, still control global design and development agendas.However, any successful movement to establish comprehensive and robust systems of new knowledge and understanding should also be able to accept multiple values,forms and definitions of research produced by and through landscape practices –including research by design.

Design and Generalizable Knowledge

Growing evidence from the f eld (ASLA, LAF, Internet, etc.)suggests that many forms of research are integrated within professional practices of landscape architecture. W e believe a variety of investigative strategies already take place in the design of f ces and construction f elds of the profession, from teams assembled for the sole purpose of solving a special problem to a director of research in a design of f ce whose job it is to assess and organize the measurable bene f ts of built projects. This new elasticity is precisely what needs to take place in order for the f eld of landscape architecture to realize its latent capacity for cross-case comparison. (see f g. 3)

In order to gain a better understanding of the current shape and scope of practical research, my colleagues and I have launched an exploratory survey to probe attitudes toward research investigations being conducted by professionals. W e also seek to test and illustrate a comprehensive framework, f rst introduced in Landscape Architecture Research: Inquiry, Strategy, Design (2011), that accounts for multiple strategies of practical research taking place in landscape architecture (T able 1).6In particular, our survey asks practitioners to relate their typical professional services and investigations to a generally accepted def nition of “research” (based on federal regulations and as adopted by the Collaborative Institutional Training Institute)that is equal parts standard and elastic: “a systematic investigation including research development, testing and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge.”7Although highly generic, we think this def nition has great utility for describing the range of practices potentially undertaken by f eld and off ce professionals. It encompasses a variety of strategies and the methods employed for each that accommodates everything from experiment to design-as-research;from participatory design process to historic interpretation; and from straight-up descriptive case study to dynamic modelling.

Early responses to our survey indicate some resistance from practitioners on the notion of generalizability, as if broader expertise is unreasonable or untenable in the pursuit of sensitive design. But what good designer does not develop overarching insights from site-specif c or project-based investigations which are relevant to other sites and settings? Yes, there are clear dif ferences in intellectual value between one-off solution-based investigations undertaken as a fee-for-service and original,generalizable research efforts undertaken solely for its knowledge value. But research practices need not be limited to such black-or-white propositions. If, in the solution of client-based problems, project information is systematically reclaimed, organized as a dataset, and rigorously analyzed according to theoretically-informed questions,then the f xed traditional boundaries between practice and research quickly become blurred. Our survey of practical research thus seeks exemplary models of professional practice that show a way forward – those not only making research a commitment but also a “brand”; not just a business model but a type of advocacy.

Table 1. Research Strategies in Landscape Architecture: A Framework for Practice(adapted from Deming & Swaff eld, 2011)

As one of the professional exemplars to be featured in our forthcoming study, Design Workshop is not alone in its pursuit of a larger professional research agenda; however this f rm’s projects are among the best examples of how professional practice is retaking the f eld of knowledge production from academia and invigorating the discourse of research. How does the work of Design W orkshop f t into our larger framework?Among the nine basic research strategies that we identify in Table 1, Design Workshop participates in at least two strategies for generalizable practical knowledge:

Descriptive Strategies include the preparation of both comparative and longitudinal case studies. Objective reporting and description of new places and/or practices belong properly to case study research. For instance, by participating in this issue of Architectural Worlds as well as in the LAF Landscape Performance Series of case studies, Design W orkshop is collecting, organizing and presenting case study data to assist in a collective understanding of the patterns of success and failures fundamental to larger problematizing and investigation. By honestly and objectively examining both the failures and successes of the work, new knowledge may be grounded or conceptual, range over an extended time frame and will always, simply by def nition, involve new social and environmental variables.

Projective Design Strategies involve what is sometimes called research-by-design.Design process as a research strategy is activated when theoretical principles or propositions are projected through design in order to re-frame existing questions or through innovation to raise new disciplinary questions.8Yes, there are compelling ethical reasons to maintain a clear separation between the interests of providing services and the interests of generating new knowledge, as in medicine. There are, however, instances where design investigations may achieve combined ends,especially where the client shares in the project goals. (see f g. 4 and f g. 5)

When projective design is harnessed to a theoretical agenda (for instance when a theory of sustainability and/or social equity suggests development of ‘complete streets’),several things can happen: (1)a new theory of generative process emerges (design theory); (2)derivative theory is applied/tested to improve the generation of new places,images, phenomena, relationships and impacts (applied research in/through design)or (3)grounded theory emerges from observation of the work produced (evidencebased design). Variations of design-as-research can thus contribute powerfully to new disciplinary knowledge. Some popular permutations, such as formal and typological/comparative analyses, more properly belong to classif cation and interpretive strategies.But all come with an important caveat: only if the purposes, procedures and results of project success and failures are reported rigorously and evaluated in an unbiased way(i.e. without bias or inherent “interest”)may we speak of design as research.

Naturally, micro-research processes inform almost all design problems: site systems must be modelled and evaluated; costs and program areas must be calculated; and so on. However, if not generalizable and shared, knowledge thus gained cannot be claimed as research. This can be confusing. Non-research corollaries of Hermeneutic Interpretation may be engaged by designers in telling stories on or about sites;understanding of artifacts and indexical traces may enrich and guide site-specif c design choices of materials and spatial sequence. Non-research corollaries of Evaluation &Diagnosis are used in every site analysis, for instance in determining the quality and depth of soils for construction or the desirability of certain views on or of f-site. Nonresearch corollaries of Engaged Action are activated every time a design team runs a public hearing or elicits feedback on schematic design or programming for a campus or park. No matter how critically valuable, however, most of these site-specif c corollary activities do not and can not satisfy the requirements of a broader research agenda.

New Knowledge & the Culture of Gatekeeping

Much outstanding practice-based research being done today in landscape architecture is emerging from new partnerships between private practice and public agencies collaborating with academics and with each other. Even the lean funding climate is supportive for these kinds of productive research alliances. Highlighting this renewed interest in research is signi f cant in two ways: f rst, it may become easier for academicians to partner with of f ces on shared research questions, satisfying both proprietary and academic/peer-reviewed dimensions; and, secondly, professional activities may soon be driven, even dominated, by larger questions of health, safety and welfare, including climate change, resource management, social justice, and public health, the statutory legitimation of the f eld.

There are points of friction to be overcome – notably in peer review and accreditation,both residual practices from a past century that weigh heavily on academics in particular. In principle, both are necessary practices, symbolic of preserving intellectual integrity through a consensual process of self-governance within a professional and/or scholarly community. But it is admittedly hard to imagine practioners subjecting themselves to the sometimes capricious, time-consuming, and often gruelling demands these procedures can place on investigators. The ages-old tradition of academic peer review model thus involves a level of risk especially for young practitioners and academics that they often cannot af ford and seek to avoid.In the frenetic pace of both contemporary media and academic funding cycles, old models of peer review are breaking down already because it simply takes too long to see high quality work in print, even on-line. If an investigator’s goal is practical impact,as opposed to, say, academic credibility or prestige, these forms of peer review might be seen as frustrating obstacles.

The new generation of academics, especially those with ambitious hybrid design and research agendas, opt to take their work to alternatives venues and audiences,with different critical and editorial agendas. Because both research and creative investigation can take many dif ferent forms, so too can peer-review. Some major research universities are now beginning to accept that many forms of critical reception,evaluation and acclaim by peer audiences may suf f ce to indicate the basic tenets of research and creative quality, including internal and external validity, absence of bias,applicability, reliability, originality, and economy.

Given these emergent practices, what forms might a peer-review process or its equivalent for practice-based research take? It undoubtedly depends on the format and the content of the work. Some journals (both print and on-line)dramatically shorten or alter the traditional peer review process or by-pass it altogether in favor of editorial, board/committee or more informal Wiki-type, continuous voluntary and consensual review processes (such as Wikipedia). Design competitions and awards programs are often reviewed by an event-specific jury chosen for their experience and critical insight whose deliberations are often conducted in an intensive and concentrated time-frame. Funding and fellowship applications and exhibitions of work are often selected in similar ways.

Collaborative work, especially with repeat clients and/or trusted project specialists,are other ways of observing peer reception. Built work, refereed studios or design projections that are published and/or critically acclaimed by recognized cultural analysts may also be accepted as forms of peer review. Given all this, it is likely that the culture of professional “gate-keeping” will continue to change, if slowly, both inside and outside the academy, despite the fact that there is still no strong consensus on the def nition, the logic, the purpose and the benef ts of research produced by and for professionals in our f eld.

Research: A Global Enterprise

The authors of professional research now include everyone – landscape practitioners in private sector design; multidisciplinary or corporate consulting f rms; not-for-prof t f rms; public sector agencies, as well as hybrid academic practitioners. Research is being produced and consumed at an accelerating pace; some have even predicted that practice-based research will challenge the traditional process of peer-reviewed publications that simply move too slowly to be relevant. Most accomplished practitioners are skilled multi-disciplinary collaborators, impatient with the “silos” of academic knowledge. Students wish to see how the research skills and methods they are learning may be translated into professional applications and, ideally , into professional employment, with signi f cant bearing on the shape/focus of professional curricula in schools of landscape architecture. All this suggests that new knowledge needs to be shared and implemented far more quickly than traditional journal models can currently handle; at the same time, it is in the interest of the profession to ensure the rigorous vetting of new ideas and practices and to be wary of the unintended consequences of ill-thought-out approaches.

As practitioners take greater responsibility for practical research, one can easily imagine the research agenda of the academy beginning to morph in response,perhaps accepting the mandate for greater impact, with a sharper focus on the production of knowledge leading to desired social and environmental outcomes.Although this may lead to more rational instrumentality, it could also change the discussion towards recognizing our shared values – what some have called value rationality.9After all, most landscape architects share certain goals in common:to create or preserve good and healthy places, build knowledge, gain mastery(technical, predictive, conceptual and ethical knowledge), ensure our continual collective improvement, and serve society. This set of core values of fers the hope that early adopters of practical research methods will stimulate better design, greater professional impact, and therefore higher aspirations for what landscape designers and planners can and should know.

In principle, the range of scales at which our ideas take shape should only strengthen the global enterprise of landscape architecture. That global enterprise is communicated through advocacy, emerging professional organizations, standards and regulation of best practices, conferences, professional curricula, mentoring and partnerships formed across disciplinary and national borders. The Chinese Society of Landscape Architecture (CHSLA)is rapidly moving the profession forward in this hugely important country and developing a system for accrediting their impressive network of schools. The International Federation of Landscape Architects (IFLA)is making important strides towards enhancing landscape architecture professionalism in Africa, South America and other regions. The Council of Educators in Landscape Architecture (CELA)is advocating and mentoring with academics in Mexico, Central and South America, and the Pacific Rim/South Asia on strengthening standards for professional education program in landscape architecture. In reality however,the global enterprise of landscape architecture is weakened when members fail to generate and share their knowledge at the same visionary level and range of scales as our professional advocates. (see f g.6)

Recognizing that landscape architecture is a relatively small professional force in a global marketplace may persuade us to re-think the role of knowledge production in developing the “competitive edge” of the profession as a whole.10In an age of innovation it is insuf ficient for any individual of fice to maintain its competitive edge without contributing to the greater knowledge base of the discipline. As Kurt Culbertson points out earlier in this issue, both talent and training contribute to maintaining a competitive edge that may be manifested at the off ce level in exemplary project-scale work as well as through broader disciplinary expertise. The attention now being paid to comprehensive development of an evidence base “proving” the values,benef ts and impact of landscape architecture signals just how important knowledge formation has become in maintaining the competitiveness of the whole profession.

When individual firms compete for work, they withhold professional services and practical expertise from their clients until a contract is signed. Yet other, perhaps larger applied design and engineering professions may like to claim they have similar expertise. This is the real playing f eld, an interdisciplinary competition for new knowledge and new impacts. By sharing general and speci f c disciplinary knowledge,all landscape architects help each other (and themselves)improve the capacity of the profession to compete at the largest scales for the highest stakes, securing signif cant public investment and making broad environmental policies and impacts. If we can compete on the playing f eld of new knowledge, we may f nally see landscape architecture maturing intellectually and finding its rightful place among the world’s important disciplines. If we can’t or won’t compete at this level, then how shall we defend landscape architecture against redundancy?

Notes:

1 Mark Francis. “A Case Study Method for Landscape Architecture.” Landscape Journal, vol. 20:1, (2001), 15-29.

2 Mark Francis. Village Homes: A Community by Design. Washington, DC: Landscape Architecture Foundation Land and Community Design Case Study Series, 2003.

3 CLARB (ERIN Research)n.d. “Landscape Architecture and Public Welfare: A Foundation Paper, Executive Summary.” Washington, DC: Council of Landscape Architecture Registration Boards. https://www.clarb.org/Documents/Welfare-execsummary-public-v1.pdf [accessed May 11, 2013]. Founded in the mid-1960s, the Council of Landscape Architecture Registration Boards (CLARB)is mandated with advocacy and protection of professional registration standards such as testing and licensing in landscape architecture. Formed to serve registration efforts in the United States, CLARB also plays an important role in advocacy and mentoring of similar organizations in other countries. “CLARB's mission is to foster the public health, safety and welfare related to the use and protection of the natural and built environment affected by the practice of landscape architecture.” https://www.clarb.org/about[accessed May 28, 2013].

4 Dennis Jerke, Douglas Porter, and Terry Lassar. Urban Design and the Bottom Line: Optimizing the Return on Perception. Washington, DC: Urban Land Institute, 2008, 16.

5 Simon R. Swaff i eld. “Empowering Landscape Ecology – Connecting Science to Governance through Design Values.” Landscape Ecology (pub. on-line June 09, 2012). DOI 10.1007/s10980-012-9765-9, n.p. In this passage,Swaff i eld cites M. De Landa and Eric Ellingsen, “Possibility Spaces” in 306090: Models. 11 (2008), 214-217.

6 M. Elen Deming and Simon Swaff i eld. Landscape Architectural Research: Inquiry, Strategy, Design. Hoboken,NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2011. Also see S. R. Swaff i eld and M. E. Deming. “Research Strategies in Landscape Architecture: Mapping the Terrain.” European Journal of Landscape Architecture, (Spring 2011), 34-45.

7 Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI). n.d. Co-Founders: Paul G. Braunschweiger Ph.D., Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, and Karen Hansen, Director, Institutional Review Off i ce, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. https://www.citiprogram.org/aboutus.asp [accessed May 11, 2013].

8 Forms of design research involving synthetic/transformational design and projective design strategies have been very capably described by S. Nijhuis and I. Bobbink in their recent article “Design-Related Research in Landscape Architecture.” Journal of Design Research, vol. 10: 4, (2012), 239-257.

9 Simon R. Swaff i eld. “Empowering Landscape Ecology – Connecting Science to Governance through Design Values.” Landscape Ecology (pub. on-line June 09, 2012). DOI 10.1007/s10980-012-9765-9, n.p.

10 Simon Swaff i eld has also argued this point in recent publications and lectures. For more in this vein, see the transcript of Swaff i eld’s 2012 Olmsted Lecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. http://www.gsd.harvard.edu/#/events/simon-swaff i eld-frederick-law-olmsted-lecture-knowing-landscape.html.

About the author:

Dr. M. Elen Deming is Professor of Landscape Architecture at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign where she teaches design studio, history and theory, and research design. Her education includes a doctorate in design from the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and degrees in Art History, Landscape Architecture, and Environmental Studies. Co-editor of Landscape Journal from 2002 with James F . Palmer, Deming assumed the role of sole editor from 2006 to 2009. She is a past President of the Council of Educators in Landscape Architecture(CELA). Deming and Simon Swaf f eld co-authored Landscape Architecture Research: Inquiry/Strategy/Design(Wiley, 2011), a framework describing several research strategies utilized in landscape architecture today . A new book that examines research emerging from professional practices, f rms and agencies is forthcoming.

Additional Biographies for Architectural Worlds (AW)

Lake Douglas

Lake Douglas, PhD, is associate professor at Louisiana State University’s Robert Reich School of Landscape Architecture, where he is undergraduate coordinator and holds the Robert S. Reich Teaching Professorship. His extensive writings on design issues have appeared in books, professional publications, academic journals, and the popular press in America and Europe. His most recent book, Public Spaces, Private Gardens A History of Designed Landscapes in New Orleans (2011)has received national recognition through numerous professional and academic awards. Douglas served as a reader and editor of the articles in this issue.

Fenglin Du

Fenglin Du is a Registered Landscape Architect in Texas who has worked on numerous projects with Design Workshop for more than ten years. She received a Master of Landscape Architecture degree from Texas A&M University in 2003 and a Bachelor of Architecture degree from Tsinghua University in 1999, where she also holds a Bachelor degree in Edition from the Department of Chinese Language and Literature. Fenglin assisted in reviewing the Chinese translations of several articles in this issue.

Pengzhi Li

Pengzhi Li graduated from Beijing Forestry University in 2008 with a Master of Landscape Architecture degree, and currently is a third year student at Texas A&M University in the Master of Landscape Architecture program. Pengzhi assisted in reviewing the Chinese translations of several articles in this issue.