DW Legacy Design®工程

作者:丽贝卡·伦纳德

DW Legacy Design®工程

DW Legacy Design®是Design Workshop开发的一种循证设计方法,旨在为项目团队提供决策制定的透明化依据。它可以使团队保持统一,并相互协作。尽管全公司的同仁们一致同意只有在实际世界的项目应用中才能真实检验这种设计的指标,但是很多项目团队都有一种共同感受,那就是除了形式创造外还必须做研究。要创建一个可衡量的流程,必须熟悉研究方法、分析并记录 广阔而深入的主题——这是在当今如此快节奏的从业者世界里难以实现的。这也许是许多从业设计师很少冒险开展研究的原因,而只有专业学者才会进行这样的研究。

DW Legacy Design®拥有一条嵌入式的反馈式循环——创造、评估、创造、评估,——它缩短了研究的学习曲线,并保证有时间来评估随着方法学的演变而日益增多的复杂内容。从项目初始一直到竣工后的监控,都在实行这种严谨的方法。在过去数年来,Design Workshop的设计师已找到将这种方法整合到项目工作的机遇和挑战。

寻找可进行DW Legacy Design®的工程

应用DW Legacy Design®的过程的第一步是赢得这项工作。客户必须愿意接受其项目在四大范畴(环境、社区、经济和艺术)内是综合性的并且可衡量的。由于鲜有实践者会尝试达到这种严谨的研究水平,因此,客户可能对这种方法的价值并不了解。设定综合目标、开发基线和寻找基准点所需的努力程度可能会遇到阻力——这些活动经费很可能已经占项目预算的三分之一了。如有必要,设计师必须“推销”这种循证设计。有一点是至关重要的,那就是设计师必须通过展示先前工作并与之分享初始水平及持续的分析其是如何使以后的项目节约成本并获益的经验,从而设定合适的期望。

自始至终都运用DW Legacy Design®方法

项目有担保之后,设计团队必须制定一项工作计划,该项计划包括对每个设计过程阶段的严谨衡量,并在完成后符合循证设计标准。团队必须快速熟悉关键问题、创新机会、批判性问题疑问、客户愿景以及客户关键成功因素(CSF)。客户愿景是客户预期的项目成果的清晰表达。这仅可通过聆听客户的表述才可形成。客户的CSF是必须实现的特征或结果,只有如此才能让客户认为这个项目是成功的,而且,在整个项目过程中,必须对客户的CSF进行评估。随着项目的进展,可能也有必要对这份清单进行修改。客户的CSF在工作范围内也许并没有被描述,所以帮助客户界定是十分重要的 。

Design Workshop团队在这个过程开始时,会与客户、团队成员及在场的关键利益相关者召开战略性项目启动(SKO)会议。与整个团队和合作者的广泛对话会使备选方案更周全,也大致议定了确定问题的方法。透明化的决策制定使各方均能够了解拟定的过程,因而对项目有统一期望。这个过程充分体现在以下范例中。

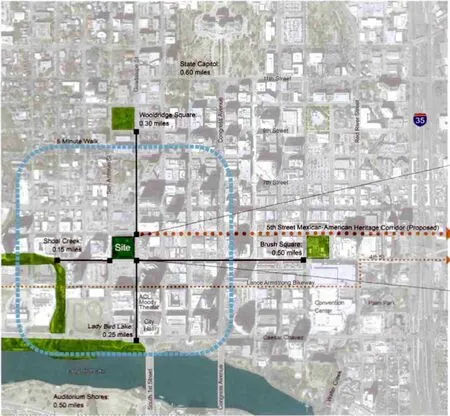

在奥斯汀公园与娱乐活动管理局的领导下,通过与利益相关者的会话,Design Workshop顾问团队针对德克萨斯州奥斯汀共和广场项目找出并确认了客户的CSF。在这个过程的构建阶段尽可能以可衡量的方式来表达每个关键的成功因素。例如,方案声明,“该项目应保存和保护现有的‘拍卖橡树’,因为 奥斯汀市的原始地皮就是在‘拍卖橡树’下出售的。”这一关于树木保护的表述当然是一个重要的普遍性问题,特别关注的是“拍卖橡树”的保存,与一般的林木保存截然相反,可以说,这也是一个批判性问题。在这个阶段,不可能让每个CSF都可衡量,因为目前的状况还是未知数,且尚未开展研究去了解什么才是合理的目标。相应的还有数种表述,如:“该项目应为多世代的使用者提供机会”,“该项目应创建一个‘标志性’公园,体现出邻里的同一性。”虽然不可衡量,但这些观点也被记录在案,构成项目团队的研究议程的基础。(参看图1)

一旦团队的基础工作确立,就必须应对关键项目的挑战,并制定相应的方法。“项目困境”是一项叙事性策略,描述的是项目的窘况。这项策略在把DW Legacy Design®运用到项目中的同时,总结了必须应对的主要挑战。在讨论项目语境的初始阶段,首先遇到的困境就是:“什么会妨碍项目取得成功?”这个问题生动地体现了项目的复杂性以及对综合解决方案的需求。这样一来,困境声明就完全不同于工作范围,也不同于客户的愿景和目标。通过团队的设计与规划调查进行检验和确定项目成果,而“项目主题”则是关于项目成果的声明。它是对核心问题或困境声明中存在的疑问的拟定解决方案。共同清晰地表明项目的伟大计划,可以使团队为了共同目标或经历团结起来。

在项目早期,团队会制定项目的困境和主题声明。由于附近的公共开放空间有限,共和国广场项目的困境在于,与其它同等规模的城市公园相比,它的使用强度更大,而且,由于对随后的运营和维护缺乏合理的规划,该公园有可能被过度使用。此外,公园的再设计包括很多利益相关者,它们是联邦政府、州政府和市政府、在活动期间经常出入该公园的社区成员、在市中心工作的人以及住在该公园附近的居民,由于再设计对他们有着多重意义,因此,获得对再设计的广泛支持变得更具挑战性。

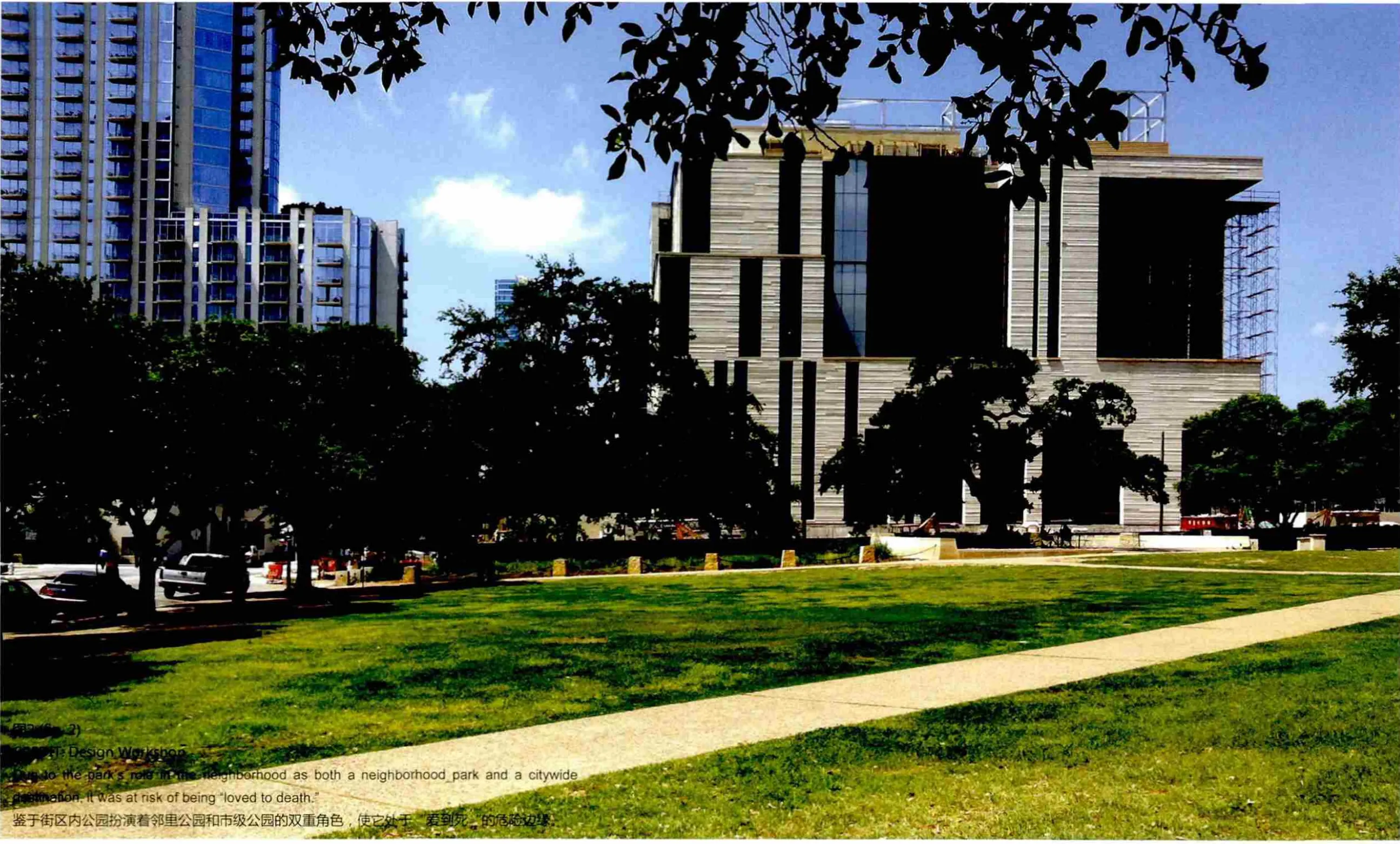

项目的主题是要承认地域的历史以及会影响该过程的其它计划;加强文化、物质、历史、艺术、情感、生态和经济方面的联系;把该公园与其它著名的城市目的地公园相比较;最后,确保实施及持续运营和维护的成本可由设计产生的附加收益所负担(如:附加销售额或财产税)。(参看图2)

叙事原则是关于项目固有的主观陈述,也是项目相关人士都了解和信服的陈述。对于DW Legacy Design®的四大范畴(环境、社区、经济和艺术),每个范畴叙事原则的清晰度对严谨、全面、以探索为导向的设计过程是至关重要的。这一做法为项目团队奠定了共同的基础,并针对主题检验作出各种设想。叙事原则可使团队在与客户的讨论以及在公开会议上更具说服力,以获得较好的效果。

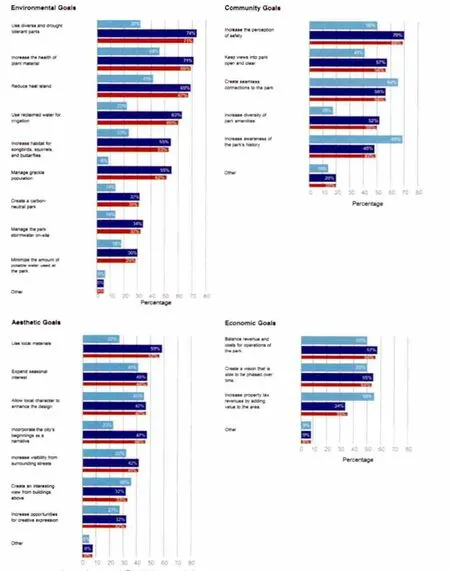

从一开始就针对四大范畴——环境、社区、经济和艺术——进行综合思考,使结果能融合进最全面的可能性与绩效指标 。项目目标对循证设计过程是必不可少的,因此,必须尽早制定,以便为分析提供信息、为备选方案创作提供指导、为持续监控提供基础。对于目标的要求 必须是明确、可衡量、可执行、实事求是、有时限,但是,这一点很难在首次团队集体讨论会上实现。在调查项目机遇,同时制定方案或者召开SKO会议的时候,Design Workshop团队会组织进行一场关于目标和指标发展的简便 对话。专门设计的“指标选择明细表”用于指导以探索为导向的讨论,并鼓励实现DW Legacy Design®四大范畴的目标。初次集体讨论后,小组会选择并优先考虑相关的研究与衡量主题、制定初始目标并强化对冗余区域的探索。这一做法有助于从一开始就形成工作范围、确定额外团队成员并确保综合性、优先化方法的制定。在设计过程的前期设定的目标的责任性是交付具有真正价值的可持续性解决方案的必要条件。对于共和广场项目,目标是通过采用键盘轮询设备的公开会议与在线投票的方式,与利益相关者公开讨论后制定的。共设定了25个项目目标,这个数字被认为可以体现项目的复杂程度;不过,不时地追踪如此多目标是难以处理的,项目团队也发现,要以同等的严谨性达成所有目标是很难的。共和广场项目的目标例子包括“增加鸟类、松鼠和蝴蝶的栖息地”和“减少热岛效应”。显然团队早期认为每个目标都有可行的措施。对团队而言,要了解如何衡量其它目标就更难了,比如:“把场地独特性真实纳入设计和规划中”。团队选择把它们视为目标,但也承认,定性衡量多于定量衡量。(参看图3)

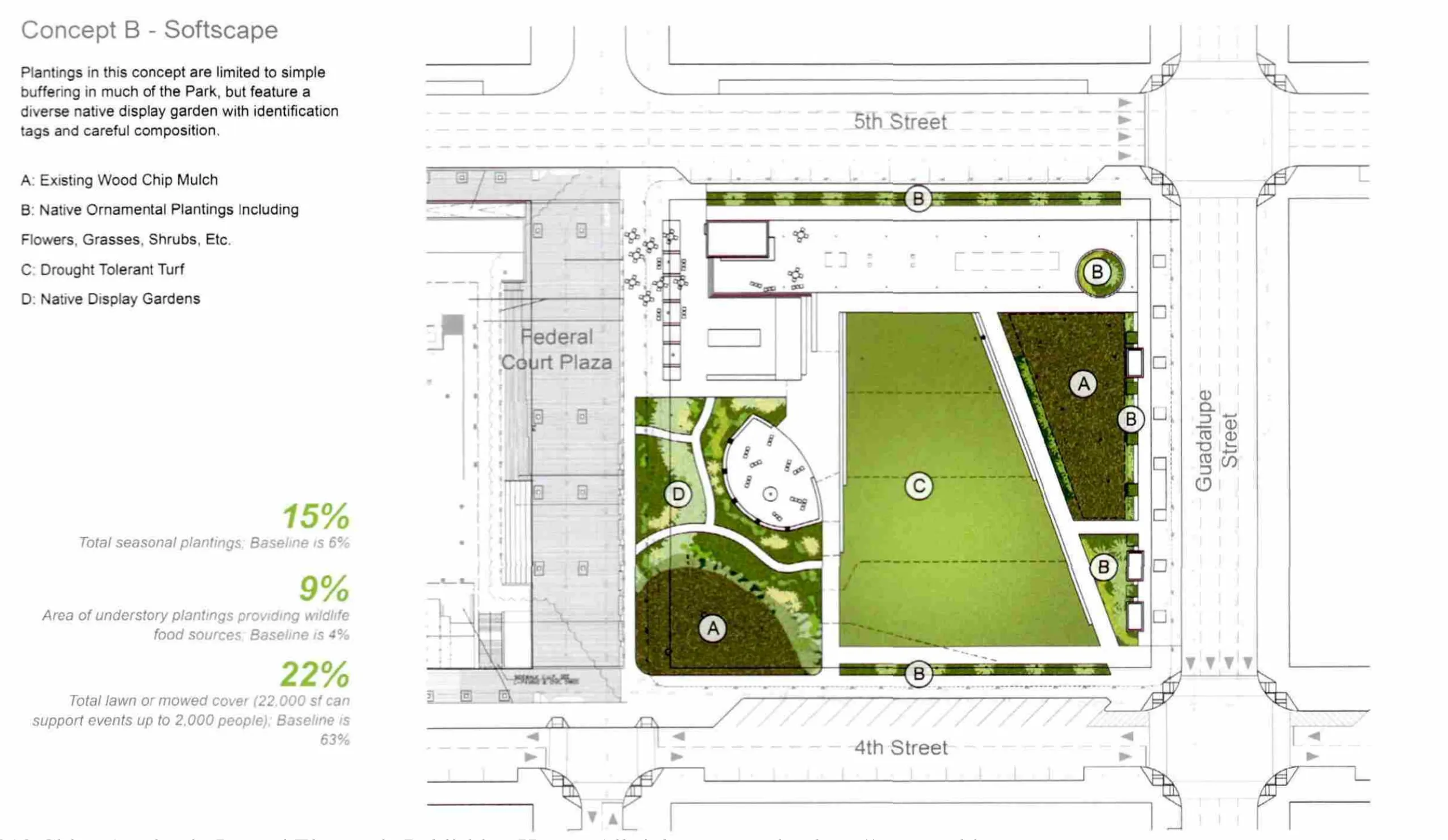

设定目标后,Design Workshop团队在现场或区域内对每个目标的现状进行研究 ,以便建立测量进度的基线。为了提供这些数字实际意义的参考点,要把基线与行业标准、最佳实践和同等设施相比较。没有这条基线,随后的衡量就没有参考意义。公司的门户网站是一个设有共享知识和信息的内部站点,其它项目所收集的以往项目经验以及完整记录的案例研究为当前项目提供了各项基准。对于共和广场项目,热岛效应是通过测定不透水表面的数量而衡量的(目前,该公园有25%的不透水表面)。栖息地是通过树冠覆盖面和下层花卉植被的百分比进行衡量的(目前,该区域有40%是被树冠覆盖的)。每个目标都可找到数据来源,否则就会以场地调查、利益相关者投票或已知事实的推论的形式进行基本研究(如:衡量光线是通过在栅格上的光照取样,并测绘出数值而得到的)。(参看图4)

接下来的工作阶段——制定和检验备选方案、安排项目进行长期监控——往往是最具挑战性的。研究是开发设计和建立备选方法证据的基本要素;不过,对于研究费用次于开拓思路和制定备选方案所需费用的项目来说,这也是一个要点。为了确保决策人充分了解信息,必须利用设计过程早期在测量基线过程中所用的相同方法对每个设计备选方案进行分析。这个步骤面临的挑战在于,制定备选方案通常占用了大部分分配时间,几乎没有或很少留时间在达成目标时对成功进行衡量。此外,若设计方案尚未完成,某些指标是很难预测的。例如,在开幕日、在种植两年后或者在植物完全成熟时,设计师如何预测备选方案的树冠覆盖面?再次以共和广场项目的非渗透表面指标为例,现状查明的不透水表面的现有数量为25%,而可同等公园的不透水表面比例为50%~60%。若这三种备选方案测得的树冠覆盖面为40~50%(现存条件与可比拟基准之间的范围),团队则认为这些备选方案是可以实现的。(参看图5)

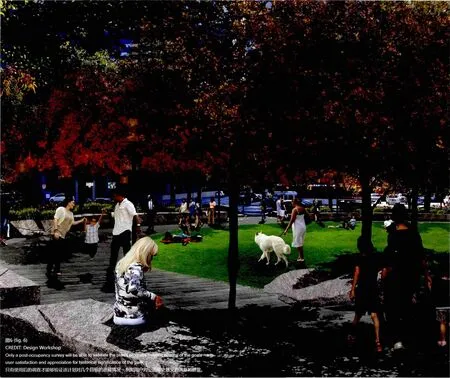

尽管强烈希望对项目施工后的绩效进行评估,但是,接受长期监控的项目的范例极少。施工图和施工监理完成后,设计师的契约通常就结束了,客户也已转移到其它事务上,未来的利益相关者(如:居民、使用者)并不清楚如何利用基线与未来测量结果进行比较。即使客户有远见去实行项目监控计划,团队人事变动、缺乏系统知识以及数据可用性的改变也使其难以继续将指标与基线、基准进行比较,因而难以长期了解项目是否获得成功。共和广场项目有望在2013年年底动工,预计在2014年年底竣工。同样地,该项目一直以来也没有监控。不过,有一些目标需要持续监控,才能确保其已达成。例如,有几个目标仅可通过对建成后公园的使用者调查才能进行衡量,如:“提高对该公园的历史意义的认识”和“通过公园设计彰显本土特征”。根据社区会议上的键盘投票及在线投票结果确定了这些目标的基线条件,那就是有50%的现有公园使用者对该公园的历史有清晰了解,并且有12%认为该公园捕捉到了“奥斯汀的精髓”。设计团队现在就提前思考这些问题,从而对这些目标的变化进行长期监控 。(参看图6)

让一个接一个的项目都建立在成功的基础之上

由于在大多数设计实践中DW Legacy Design®方法并不常见,还需要一段曲折的经验,因此,将这个过程确立的初始成本很高。为了在市场竞争中立于不败之地,设计实践必须更加高效。从一个项目到另一个项目,团队成员必须继续运用其在先前工作中获得的经验。对于某些项目类型,有些指标一直都非常有用。例如,几乎对所有的街道景观和公园项目来说树冠覆盖面都是至关重要的,它的作用包括:减少径流、减少热岛效应和提高人类的舒适度。对几乎所有政策计划而言,重要的是提供优质的、人们买得起的住房。项目团队能够从一个接一个的项目获得宝贵的专业知识,因此不必花太多的时间和精力进行研究和评价结果。

分享经验教训和系统知识的正规机会具有双重益处,其一是让那些不愿尝试严谨指标追求的团队成员有机会向更富经验的成员聆听和学习,其二它提供了一种认知方式给较早接受的成员,他们是一批早于别人勇敢尝试高质量研究的人。此外,如果已经看到其他项目带来的积极成果,团队更有可能采用方法学或开展研究,因此,要熟悉以往取得的成功也十分关键。

项目团队最初面临的一些挑战是,他们企图追踪过多的指标,而根据经验,如何区分指标的优先次序才是成功的关键。与内部人员分享范例非常重要,这样团队才不会从零开始——Design Workshop一直在内部推广这种做法。Design Workshop已开发出一种“可持续性矩阵”,这份文件至关重要,可以追踪各种目标及策略、任务、基线、基准和研究原始资料,尤其是在多学科团队工作时。该工具在公司的门户网站也有直接链接 ,因此,团队能够即刻查到潜在指标的相关信息。若每个潜在指标主题都有充分的且易于得到的研究和基准,则可以减少花在研究和“发明”相关数据库的时间,从而使团队成员能够把分配的研究时间花在寻找更佳的信息或者更具相关性的新比较基准上面。项目计划书模板使团队能够从某些既定的DW Legacy Design®内容开始制定项目文件。由于整个公司的团队都是采用相同的模板,因此可以把一个项目的相关研究结果快速转移到下一个项目中。在项目进行中,访问Design Workshop的门户网站已成一个较为常见的步骤——在设计和施工过程中,员工既 取出也存入知识。

最后,宣传各项指标,这是至关重要的!Design Workshop已开发出各种方法庆祝成功,并通过DW Legacy Design®奖励计划,对员工提交主题会议论文进行鼓励,以及出版关于公司实践和项目的文章和书籍,来将这些信息传播到公司内。如果与哲学信仰相一致,积极的强化能够有助于产生有策略、有远见的行动。

应对挑战

Design Workshop将DW Legacy Design®方法运用于各个项目中,经历过众多的挑战,力求克服数十年来对在景观建筑与规划领域中的研究自满情绪。这些挑战可分成几大类,包括:缺乏积极性,缺乏基于研究设计的过程机制,对未知事物存在恐惧心理。缺乏积极性通常是因为缺乏对指标益处的认识。设计师必须要有一个强有力的理由,说明基于指标的设计方法诸如:DW Legacy Design®如何让设计精益求精,同时也能为客户省钱。偶尔会出现这样的情况:团队在整个设计过程中缺乏自律性,而没有在过程中追踪各项指标。阿图·葛文德在《清单革命》(2009年)里捕捉到了这一现象,他指出,“不过,我们需要的不仅仅是在一起工作的人要相互友好,还需要自律。自律是困难的——比信任和技能还难,甚至可能比无私更难。我们天生就是有缺陷的,是变化无常的生物。我们甚至无法克制自己在两餐之间不吃零食。我们生来就不是自律的。我们生来就追求新颖和刺激,而不是仔细关注细节。自律是我们必须处理的工作。”作为项目的领导者,主管和项目经理都必须提倡这种严谨性和可衡量性。从签订合同到项目的最终实施,如果团队领导人并没有表明其对可衡量价值的信任,那么,这种可衡量性就是无谓的了。

第二类挑战与研究机制有关。如前所述,对新接触诸如DW Legacy Design®过程的团队往往会考虑太多的指标,因为实际上还有一种学习曲线,可以针对给定的项目类型对指标进行编辑并区分指标的优先次序。事实上,在项目启动时建立一致意见时所付出的努力是对日后追踪指标的顺畅过程的投资。区分优先次序时,除了考虑数据的规模和发布频率,还要考虑数据的可用性。

图1 (fig. 1)CREDIT: Design WorkshopThere were 1,508 dwelling units within a 1/4 mile of Republic Square in 2010 - up from 372 dwelling units in 2000. 在2010年,共和广场的1 / 4英里内有1508个住宅单位— 而在2000年,只有372住宅单位。

图2 (fig. 2)CREDIT: Design WorkshopDue to the park’s role in the neighborhood as both a neighborhood park and a citywide destination, it was at risk of being “loved to death.”鉴于街区内公园扮演着邻里公园和市级公园的双重角色,使它处于“爱到死“的危险边缘。

没有一个项目经理可以单独实施这一设计过程。如果团队成员对统计学和统计分析有基本的认识,且了解看待项目及衡量项目绩效的不同方法,那么,团队的效率就会有所提升。这种学术含意在于,可以表明把基础统计学纳入景观建筑课程所带来的价值。

包括分包顾问和利益相关者的团队应努力做到节约时间和资源,并抓住创新机会。公司和项目领导层的支援有助于团队了解这些节约和机会。办公室的其他人必须支持团队的愿景,并帮助填补知识空缺和应对挑战。经常为项目团队提供机会进行工作汇报,并从外部资源获取新的见解,可以确保团队更严谨地运用这种方法。强化DW Legacy Design®的其它方式还包括:拥有可使团队通过研究调查和指标应用来加快设计周期的工具,例如ArcView和BIM;投资于既适合于外行读者又具有学术严谨性的写作方式培训;提供关于如何用图表表达指标的实例和培训。

团队开发的指标往往是设计行业或学术界的其他人尚未研究过的,这使基准的建立具有挑战性。这说明实践者有机会与各机构合作来支持研究。有些人可能会问,私营公司是否应该或能够以正规的学术方式来开展研究?这包括以下问题:需要从学术界获得什么才能开展实践?怎样的学术研究对实践有意义?实践者开展的研究能否也符合学术研究的标准?课程开发的意思是什么(有无必要开发创造力和批判性思维能力)?研究方法和统计学是否应该成为景观建筑课程的一部分?这对那些旨在把学生教育培训成从业者的计划来说有什么意义?实践者是否应该参与学术出版物的同行评议文章,将其来作为一种反馈形式 ?

这种学术界/实践者合作类型的成功范例是:Casey Trees and Davey Tree专业公司构思和开发的、美国林务局支持的“国家树木价值计算器”。Design Workshop持续提供具有学术质量的研究(例:同行评议),比如即将在爱丁堡大学建筑系学报主办的《爱丁堡建筑学研究》杂志发表的一篇文章,文章的主题是Design Workshop的路易斯安那州新奥尔良拉斐特绿道规划。尽管面临着相关的挑战,关于如何付出努力还是有很多要说的。

最后一类挑战打着“害怕”的旗号。谚语“知识就是力量”可用于激发对赋权和威胁的感受,这主要取决于掌握知识的人。无论出于什么原因,一些决策人和利益相关者都可能对数据表示怀疑,或者可能会主动尝试用他们不熟悉的知识去阻挠设计过程取得的进展。合理的研究可用于追究掌权人的责任,这可能会有点可怕。不过,决策过程越透明,决策过程及其结果就可获得更多的支持。重要的是,设计师应非常明确地指出收集数据的目的,而这往往是需要注意措辞的。有时候,要在目标上达成一致意见是不可能的——例如,“使温室气体比基线情况减少XX%”。指标——“使温室气体比基线情况有所减少”——可能更顺耳一些。要在项目工作中运用DW Legacy Design®会面临许多挑战,但通过发展知识体系和支持更严谨的研究标准,每个挑战都是可克服的。

图3 (fig. 3)CREDIT: Design WorkshopA community meeting and on-line poll were used to validate goals and determine priorities for the project. 社区会议和在线调查被用来验证目标和确定项目的优先权。

证明我们的价值

随着行业日益把循证设计作为准则,实践者在基于研究的设计过程(如:DW Legacy Design®)中扮演的角色正在演化是实践者可能在设计过程的“创造”阶段处于最佳状态;不过,他们会发现自己对创造结果进行“评估”的阶段会越来越认真负责。靠直觉或纯粹靠坊间证据判断某个构思的价值渐渐地不被大家认可了。设计师必须寻找那些同样努力寻求严谨性和自律性的客户、学者和专业同行(同伴)来促进设计行业更好的发展并提升项目的可持续性。Design Workshop已找到把这个理论运用于项目工作所面临的机遇和挑战——这种努力的参照基准极少。但是,这种努力的回报不仅仅是获得各个第三方组织的肯定(如:美国景观建筑协会、美国规划协会、美国新城市主义协会和城市用地学会),而且还因知道我们的努力目的是推动景观建筑与规划行业的永久发展,所以也令人颇具成就感。用医药诺贝尔奖得主亚历克西斯·卡雷尔的话说,“对于那些愿意克服惰性的人而言,生活如泉涌般绽放。”

图4 (fig. 4)CREDIT: Design WorkshopMeasures for each goal were determined; then, baselines were compared to other desirable urban parks. 确定每个目标的措施;然后,将基线与其他理想的城市公园进行比较。

图5 (fig. 5)CREDIT: Design WorkshopEach alternative was assessed according to how well it measured up to stated project goals.每个选择方案根据符合规定项目目标的优劣进行评估。

丽贝卡·伦纳德是Design Workshop的总裁,在社区规划、城市设计、重建、旅游规划、区域规划和场地设计方面拥有丰富的经验。丽贝卡毕业于印第安纳州曼西波尔州立大学建筑与规划学院,并获得城市与区域规划硕士学位。她在公私营规划行业的经验使其在设计行业中往往有独特的见解。丽贝卡认为,一个出色的设计需要将各个方面的背景都考虑在内——包括环境、社区、艺术与经济。

DW Legacy Design®Work

DW Legacy Design®is a method of evidence-based design developed by Design Workshop in order to provide project teams with a transparent foundation for decision-making. Legacy Design keeps teams unified and aligned. During the early days of Legacy Design, associates throughout the f rm agreed that the true test of this design method’s merit lay in its application to real world projects, yet a feeling permeated many project teams that the necessary research was something completed outside the process of form-giving. The act of creating a process that is measurable requires skill in research methods, analysis, and documentation of both broad and deep subject matter - a practice that is often diff cult to deliver in the fastpaced practitioner’s world. This is perhaps why many practicing designers rarely venture into research, and those that do are often involved with academics.

DW Legacy Design®has a built-in feedback loop - create, evaluate, create, evaluate- that shortens the learning curve for research and provides time to evaluate increasingly more sophisticated material as the methodology evolves. This rigorous approach is ingrained in a project from its inception through post-completion monitoring. Over the last several years, Design W orkshop’s designers have found opportunities and challenges to integrating it into project work.

Finding Work that Allows for DW Legacy Design®

The f rst step in the process of applying DW Legacy Design®is winning the work.The client must be open to the project being comprehensive and measurable in four broad categories - environment, community, economics and art. Because few practitioners attempt this level of research rigor, clients may not understand the value of the approach. There may be resistance on the level of effort required to set comprehensive goals, develop baselines, and f nd benchmarks - activities that may potentially represent a third of the project’s budget. When necessary, the designer must be capable of “selling” evidence-based design. It is essential that the designer set proper expectations by showing examples of previous efforts and sharing stories of how this level of early and continued analysis can lead to cost savings and benef t later in projects.

Employing the DW Legacy Design®Approach from Start to Finish

Once a project is secured, the design team must develop a work plan that includes rigorous measurement at each phase of the design process and meets the standard of evidence-based design at its conclusion. The team must quickly become acquainted with key issues, opportunities to innovate, critical questions, Client Vision and Client Critical Success Factors (CSFs).iA Client Vision captures the client’s articulation of what the outcome of the project will be. This vision can be developed only by listening to the client. The client’s CSF are the features or results that must be accomplished in order for the client to consider the project a success, and these should be evaluated through the course of the project. It may become necessary to revise the list as the project evolves. Client CSFs may or may not be described in the scope of work so it is important to help the client def ne them.

The Design Workshop team begins this process with a Strategic Kick-Of f (SKO)meeting with the client with team members and key stakeholders present. Inclusive conversations with the entire team and collaborators result in more thorough alternatives and broadly agreed upon approaches to identi f ed issues. Transparent decision-making allows all parties to understand thought processes, resulting in a unif ed project vision. This process is illustrated in the following example.

The Design Workshop consultant team identified and confirmed the following Client CSFs for the Republic Square project in Austin, Texas, with leadership from the Austin Parks and Recreation Department and through conversations with stakeholders.(see f g. 1)To the extent possible at this formative stage of the process, each critical success factor was expressed in a manner that would suggest measurability. For example, the plan states, “The project shall preserve and protect the existing ‘Auction Oaks’ under which the original plats of the city of Austin were sold.” This statement about tree preservation, certainly an important general issue,concerns the preservation of the ‘Auction Oaks’ in specific, as opposed to being a statement about tree preservation in general, arguably a critical issue as well. It was not possible to make each CSFs measurable at this stage because the current conditions were unknown and the research had not been conducted to know what a reasonable target was. Accordingly, there were several statements such as “The project shall provide opportunities for multi-generational users” and “The project shall create a ‘signature’ park, ref ecting the identity of the neighborhood.” Although immeasurable, these sentiments were logged and formed the basis of the project team’s research agenda.

Once the groundwork with the team is laid, the key project challenge and approach must be developed. The Project Dilemma is a narrative device that describes a project’s predicament. It sums up the major challenges that must be addressed while applying DW Legacy Design®to a project. Beginning with a discussion of the project’s context, a dilemma answers the question: “What is standing in the way of a project’s potential for success?” It renders vivid the complexities of the project and the need for a comprehensive solution. In this way, a dilemma statement is entirely different from the scope of work or the client’s vision and goals. The Project Thesis is an assertion about the project outcome that will be tested and resolved through the team’s design and planning investigations. It is a proposed solution to the central problem or question stated in the dilemma statement. Collectively articulating the big idea of the project aligns the team to a common goal or story.

Early in the project, the team develops the project’s Dilemma and Thesis statements. With limited public open space nearby, Republic Square’s Dilemma is that it is subject to more intense use than other comparably sized urban parks, and without adequate planning for subsequent operations and maintenance, the park faces the possibility of being overused. Furthermore, the challenge of achieving broad support for the park’s re-design is complicated by its significance at many levels to stakeholders, including federal, state and city governments, members of the community who frequent the park during events, people who work downtown,and residents living near the park.

The Thesis for the project is to acknowledge the history of the site and other plans that will inf uence this process; to enhance connections - cultural, physical, historical,artistic, emotional, ecological, and economic; to compare the park to other outstanding urban destination parks; and f nally to ensure that the costs of implementation and ongoing operations and maintenance can be borne by the added revenue created by the design (e.g. additional sales or property taxes). (see f g. 2)

Narrative Principles are inherently subjective statements about a project, but ones that are commonly understood and believed by a project’s constituents.The articulation of narrative principles in each of the four DW Legacy Design®categories (environment, community, economics and art)is central to a rigorous,comprehensive, discovery-oriented design process. The exercise lays a common foundation for the project team with assumptions against which the Thesis can be tested. Narrative Principles help the team argue persuasively for a good outcome with clients and in public meetings.

Comprehensive thinking from the beginning in four categories - Environment,Community, Economics and Art - yields outcomes that integrate the fullest range of possibilities and metrics for performance. Essential to the evidence-based design process, project goals must be developed early in order to inform the analysis, guide the creation of alternatives, and provide the foundation for on-going monitoring. The desire is that goals be SMART (Specif c, Measurable, Actionable, Realistic and Time-Specif c)ii, but this is rarely achieved at the f rst team brainstorming sessions. A Design Workshop team will lead a facilitated dialogue about goals and metrics at the point of investigating a project opportunity, when developing the proposal, or when convening the SKO. Specially designed Metrics Selection Sheets are used to guide a discoveryoriented discussion and encourage goals in all four DW Legacy Design®categories.Once the initial brainstorm occurs, the group will select and prioritize pertinent research and measurement topics, develop initial goals, and consolidate redundant areas of exploration. The benef ts of this effort can help develop a full scope of work,identify additional team members, and ensure a comprehensive and prioritized approach from the beginning. Accountability to goals set early in the design process is required to deliver real value and truly sustainable solutions.

For Republic Square, the goals were developed in an open forum with the stakeholders, through both a public meeting where keypad polling devices were used and an on-line poll. There were 25 project goals, a number considered to be necessary given the project’s complexity; however, tracking this many goals at times seemed unwieldy, and the project team found it dif f cult to approach all goals with equal rigor. Examples of goals from Republic Square include “increase habitat for birds, squirrels and butter f ies” and “reduce heat island ef fect.” It was apparent to the team early that there were feasible measures for each of these goals. Other goals were more dif ficult for the team to understand how to measure, such as“incorporate truly site speci f c cues into design and planning.” The team chose to keep them as goals but to acknowledge that the measure would be more qualitative than quantitative. (see f g. 3)

After setting goals, the Design W orkshop team researches existing conditions of each goal on the site or within the community in order to create a baseline from which progress will be measured. To provide a point of reference for what these numbers actually mean, baselines are compared to industry standards, best practices, and comparable facilities. Without this baseline, there is no point of reference for the meaning of subsequent measurements. Previous project experience and welldocumented case studies housed on the f rm’s portal, an internal website for sharing knowledge and information, provide benchmarks. For Republic Square, heat island effect was measured by the amount of impervious cover (25 percent of the park is impervious surface today). Habitat was measured by percent of tree canopy and flowering understory (40 percent of the site has tree canopy today). A source for data was found for each goal or primary research was conducted in the form of site surveys, stakeholder polls or inferences from known facts (e.g. light was measured by sampling the light on a grid and then mapping the values). (see f g. 4)

The next phases of work - developing and testing alternatives and setting up the project for long-term monitoring - are often the most challenging. Research is the essential ingredient of developing designs and building evidence for alternate approaches; however, this is also a point in the project where the expense of the research becomes secondary to that of developing ideas and producing alternatives.To ensure decision-makers are adequately informed, each design alternative must be analyzed with the same methodology used earlier in the process to measure baselines. The challenges with this step are that the creation of alternatives typically takes most of the time allotted, leaving little time, if any , for measuring success at reaching goals. Also, some metrics are dif ficult to predict for un-built design proposals. For example, how does a designer forecast tree canopy for the alternatives - on opening day, two years from planting, or at full maturity? Using the impervious surface metric again for Republic Square, it was determined that the existing amount of impervious cover was 25 percent and the comparable parks were between 50 and 60 percent impervious cover. When the three alternatives were measured between 40 and 50 percent (a range between existing conditions and the comparable benchmarks), the team believed that the alternatives were within the realm of possibilities. (see f g. 5)

Despite strong desires to evaluate a project’s post-construction performance, there are few examples of setting up a project for long-term monitoring. The designers’contracts are typically complete after construction documentation and observation, the clients have moved onto other matters, and the future stakeholders (e.g. residents,users)are not aware of the baselines with which to compare future measurements.Even if the client has the foresight to set up a monitoring program, team turnover ,loss of institutional knowledge, and changing availability of data makes it dif ficult to continue to compare metrics to baseline and benchmark conditions for a longterm understanding of a project’s success. Republic Square is expected to begin construction in late 2015 with completion scheduled for late 2016. As such, there has been no monitoring. However, a few goals will require on-going monitoring to ensure that they have been reached. For example, several goals such as “increase awareness of the Park’s historical significance“ and “allow local character to shine through in the design of the Park” can only be measured by surveying the park users post-construction. The baseline conditions for these goals, determined from keypad polling at community meetings and an on-line poll, is that 50 percent of current park users have a clear understanding of park history and 12 percent think the park captures the “essence of Austin.” By having the forethought to ask these questions now, the team is set up to monitor changes in these goals over time. (see f g. 6)

Building on Success from One Project to the Next

Because the DW Legacy Design®approach is atypical for most design practices and requires a steep learning curve, the initial cost of navigating this process can be high. To stay competitive in the marketplace, a design practice must become more efficient over time. From project to project, the team members must continue to apply the knowledge gained from their previous work. Based on project type, some metrics are consistently useful. For instance, tree canopy is important to almost all streetscape and park projects and achieves a variety of goals, including reduction in runoff and heat island ef fect, and improving human comfort. Accessibility to quality affordable housing is important to nearly all policy plans. A project team can gain valuable expertise from one project to another reducing the time and ef fort necessary to conduct research and evaluate outcomes.

图6 (fig. 6)CREDIT: Design WorkshopOnly a post-occupancy survey will be able to validate the plan’s progress towards several of the goals - e.g.user satisfaction and appreciation for historical signif cance of the park. 只有使用后的调查才能够验证该计划对几个目标的进展情况 — 例如用户对公园历史意义的满意和赞赏。

Formalized opportunities to share lessons learned and institutional knowledge will have the dual bene f ts of allowing team members who have been reluctant to attempt a more rigorous pursuit of metrics the opportunity to hear and learn from more experienced team members whilst also providing a form of recognition and acknowledgement for the early adopters, those brave enough to attempt quality researches earlier than others. In addition, teams will be more likely to use a methodology or conduct research if they have seen positive outcomes on other projects, so familiarity with past successes becomes critical.

Some initial challenges for project teams were that they attempted to track too many metrics, and experience has taught that how to prioritize metrics is critical to success. It is important to share examples within the off ce so that no team is starting from scratch - a practice Design W orkshop continues to promote internally.Design Workshop has developed a Sustainability Matrix, a crucial document to track all goals and strategies, assignments, baselines, benchmarks and research sources, especially when working in a multidisciplinary team. This tool links directly to the f rm’s portal so the team can have instant access to the relevant information about a potential metric. Having adequate research and benchmarks on each potential metric topic easily accessible reduces time spent researching and ‘inventing’relevant data bases, thereby allowing team members to spend allocated research time f nding better information or more relevant new benchmarks for comparison.A project book template allows teams to begin a document with certain DW Legacy Design® content already in place. With teams across the firm using the same template, relevant research can be quickly transferred from one project to the next. The Design Workshop portal has become a more regular step in project development - with staf f making both withdrawals and deposits of knowledge throughout the course of the design and implementation effort.

Finally, it is essential to proselytize about metrics! Design W orkshop has developed methods to celebrate successes and spread the word firm wide through its DW Legacy Design®Awards program, through encouragement of staff to submit session papers on the topic, and through publishing articles and books about f rm practices and projects. Positive reinforcement, if aligned with philosophical beliefs, can lead to action that is strategic and forward-thinking.

Solving Challenges

In an attempt to overcome decades of research complacency in the fields of landscape architecture and planning, Design W orkshop has experienced numerous challenges applying the DW Legacy Design®approach to projects. These challenges fall into several categories including lack of motivation, the mechanics of a research-based design process, and a fear of the unknown. The lack of motivation typically stems from a lack of awareness of the bene f ts of metrics. A strong case must be made by the designer illustrating how a metric-based design approach,such as DW Legacy Design®, has produced design excellence while simultaneously saving money for clients. Occasionally, there is a situation where the team is not disciplined enough to track metrics throughout the process. Atul Gawande captures this phenomenon in The Checklist Manifesto (2009)when he says, “What is needed, however, isn't just that people working together be nice to each other. It is discipline. Discipline is hard-harder than trustworthiness and skill and perhaps even than self essness. We are by nature f awed and inconstant creatures. We can't even keep from snacking between meals. W e are not built for discipline. W e are built for novelty and excitement, not for careful attention to detail. Discipline is something we have to work at.”iiiAs project leaders, the principal and project manager must advocate for this level of rigor and measurability. From developing the contract to the f nal implementation of the project, measurability will be futile if these team leaders do not demonstrate their belief in its value.

The second group of challenges relates to the mechanics of research. As discussed earlier, teams new to a process such as DW Legacy Design®will often consider too many metrics because there is even a learning curve for editing and prioritizing metrics for any given project type. In fact, any efforts used building consensus at the initiation of the project will be investments in a streamlined process of tracking metrics later on. The prioritization effort should consider the availability as well as the scale of the data and how frequently it is released.

No project manager can implement this design process alone. Team effectiveness increases if there are team members who have a basic knowledge of statistics,statistical analysis, and understand the dif ferent ways of looking at projects and measuring their performance. This has academic implications in that it suggests the value of including basic statistics in the landscape architecture curriculum.

Teams, including subconsultants and relevant stakeholders, will respond to time and resource savings and opportunities to innovate. Reinforcement by both f rm and project leadership will help a team understand these savings and opportunities. The rest of the of f ce must support the team’s vision and help f ll in gaps in knowledge and address challenges. Offering frequent opportunities for a project team to present its work and gain new insights from outside sources will ensure a more rigorous application of this process. Other ways of reinforcing DW Legacy Design®include having tools available that allow a team to rapidly cycle through research inquiries and metrics undertakings such as ArcView and BIMiv, investing in training on how to write in a way that is both appropriate for a lay audience but also academically rigorous,and supplying examples and training on how to graphically illustrate metrics.

Often, a team will develop a metric that simply has not yet been researched by others in our industry or the academy, making establishing benchmarks challenging.This presents an opportunity for practitioners to work with institutions to support research. Some ask whether private firms should be, or are even capable of,conducting research in an academically valid way, with questions such as the following: What does practice need from academia? What academic research is important to practice? Can practitioners conduct research that also meets the standards of academic research? What does this mean in terms of curriculum development (the need to develop both creative and critical thinking skills)? Should research methods and statistics be part of the landscape architecture curriculum?What does this mean to those programs that are focused on educating students and preparing them to be practitioners? Should practitioners participate in peer-reviewed articles in academic publications as a form of feedback?

A successful example of this type of academy/practitioner collaboration is the National Tree Benefit Calculator, conceived and developed by Casey Trees and Davey Tree Expert Company with support from the United States Forest Service.Design Workshop continues to provide academic quality research (i.e. peer reviewed)such as a 2013 article in the Edinburgh Architectural Research, a journal of the Department of Architecture at Edinburgh University, on Design W orkshop’s Laf tte Greenway and Corridor Plan in New Orleans, Louisiana. There is much to be said about putting in the effort despite the associated challenges.

The f nal group of challenges falls under the banner of “fear.” The phrase “knowledge is power” can be used to conjure up feelings of both empowerment and threat depending on who has the knowledge. Some policy-makers and stakeholders may,for whatever reason, distrust data or actively try to thwart progress derived from a process with which they are not acquainted. Sound research can be used to hold those in power accountable, which can be scary. However, the more transparent the decision-making process, the more support there is for the process and its outcomes. It is important that the designer make very clear the purpose for collecting the data, and often this is a matter of choosing the right words. At times, consensus on targets is impossible - “reduce greenhouse gas from baseline conditions by XX percent,” for example. Indicators - “reduce greenhouse gas from baseline conditions” - may be more palatable. There are many challenges to implementing DW Legacy Design®in project work, but each can be overcome by growing a body of knowledge and supporting more rigorous research standards.

Proving Our Worth

The role of the practitioner in a research-based design process such as DW Legacy Design®is evolving as the industry increasingly accepts evidence-based design as the norm. Practitioners may be best at the “create” stages in a design process;however, they are finding themselves more and more responsible for the steps that require that they “evaluate” the results of their creations. Judging the worth of an idea on intuition or on purely anecdotal evidence is growing less acceptable.Designers must f nd clients, academics, and professional peers (teammates)that strive for the same rigor and discipline to help advance the design industry toward better, more sustainable projects. Design W orkshop has found opportunities and challenges to applying the theory to project work - an effort that has few benchmarks. But the ef fort has been rewarded with not only third-party validation from organizations such as the American Society of Landscape Architects, American Planning Association, Congress for the New Urbanism, and the Urban Land Institute, but also immense satisfaction for knowing our ef forts are advancing the professions of landscape architecture and planning forever. In the words of Alexis Carrel, the Nobel Laureate in Medicine, "Life leaps like a geyser for those willing to drill through the rock of inertia."v

Notes:

i PSMJ Resources, Inc., Project Managers Bootcamp Manual, 2003.

ii G. T. Doran. “There is a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management's goals and objectives.” Management Review,Volume 70, Issue 11(AMA FORUM), (1981), 35-36.

iii Atul Gawande, The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right. New York, New York: Picador, 2009, 183.iv Computer software used as spatial databases by professionals in the industry.

v Alexis Carrel. BrainyQuote.com, Xplore, Inc., 2013. http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/a/alexiscarr158387.html [accessed May 30, 2013]. Read more at http://www.brainyquote.com/citation/quotes/quotes/a/alexiscarr158387.html#bRqZmV38JTjoEpUv.99.

- 世界建筑导报的其它文章

- AW访谈:李翔宁+Jeffrey Johnson