INVESTIGATING ACCEPTABILITY OF CHINESE ENGLISH IN ACADEMICWRITING

JOEL HENG HARTSE and LING SHI

University of British Columbia

Scholarly interest in the possibility of China English (CE) has expanded recently as the importance of the English language in Chinese education and society continues to grow. However, there have yet been few studies which examine the putative forms of CE in tandem with attitudes about CE in an educational context. Using an acceptability judgment task (AJT) and interviews involving 30 Chinese teachers of English evaluating English texts written by Chinese university students, this study explores participants’ beliefs, attitudes, and ideologies about the variety of CE and its potential or emerging characteristics. The study suggests that rejection of CE as an abstract concept may be related to labeling writers’ usage as unacceptable “Chinglish.” While English usages perceived as clearly influenced by the Chinese language are more likely to be rejected, the frequency of rejections forms a continuum illustrating a degree of acceptance for some potential features of CE.

INTRODUCTION

China represents an exceptional case in the study of English in the era of globalization. According to one popular paradigm, the world Englishes (WE) approach, China is a country in the “expanding circle,” where there is no use of the language intranationally between non-native English speakers, where the language has had no previous colonial status, and where it is used in limited domains, such as education, tourism, and occasionally, media. Similarly, China is known as a country where English is learned as a foreign language (EFL), as opposed to the English as a Second Language (ESL) learning that may take place in an English-dominant environment such as the United States, Canada or Australia. Strictly speaking, this is an accurate way to describe English in China, but it does not go far enough in describing the important role the language plays in the country; English is a pillar of the educational system in China and is essential for passing exams at every level. English proficiency—measured quantitatively in exam scores and certificates, or interpreted qualitatively by time spent studying abroad or working for foreign companies—has come to be viewed as an important ticket to middle-class success. As these roles for English have become more and more well-established, especially in the last decade, scholars have increasingly begun entertaining the notion that there is a “Chinese English” (also called “China English”) emerging, analogous to English varieties in countries like Singapore and India, though with characteristics unique to China.

In fact, this “uniqueness”—China as an EFL, expanding circle country whose government has embraced English on its own terms as part of a long-term strategy for successful integration into the globalized word—has challenged scholars in terms of what sociological and linguistic categories to search for and what theoretical approaches to follow. In this paper, we first review the concept of China English (CE) in a world Englishes context and empirical studies on attitudes to CE to highlight gaps that should be addressed as research continues. We argue that academic writing at the university level is a legitimate and important site for investigating the growing interest in whether CE is indeed emerging as a unique variety, and present some data from a currently ongoing study using an Acceptability Judgment Task (AJT) involving university English instructors evaluating student writing to illustrate a realistic and nuanced picture of attitudes toward uses of English in China at the moment.

CHINA ENGLISH IN A WORLD ENGLISHES CONTEXT

English has long been regarded as an important foreign language in China, but scholars there have recognized the need to contextualize English in a way that accommodates local needs. Ge (1941) was an early proponent of such a view; in the introduction to his writing textbook, he calls materials produced in English-speaking countries “quite useless” for Chinese students’ learning of English composition (qtd. in You 2010: 75). Credited with the notion that China could have its own variety of English, Ge (1980) argues that “China English” should be recognized as necessary in Chinese-to-English translation with examples such as “eight-legged essay,” “four modernizations,” andbaihua(a vernacular Chinese literary movement) which do not exist in American or British English. He refers to these terms and other unique features of English developed in China as 中国英语 or “China English” rather than 中式英语 (“Chinese English,” also called “Chinese-Style English” or “Chinglish”), the latter being a mostly pejorative term that more often refers to learner error or, in recent years, to inappropriately translated or humorous “decorative English” (McArthur 1998: 27). Jiang (2003) suggests that Ge’s motivation was in part to replace the pejorative “Chinglish” with a positive term which matched the reality of the need for uniquely Chinese words in English.

Whatever the terminology, the idea that a uniquely Chinese English exists or should exist has had currency since the 1980s. Li (2007: 16) even advocates a “radically restructured curriculum” based on the acknowledgment of CE. Believing that “it [is] important for the international English-speaking community to become familiar with” CE (Xu 2010: 205), Chinese scholars, however, have debated how it should be defined. For example, He and Li (2009: 83) propose to define CE as a

performance variety of English which has the standard Englishes as its core but...colored with characteristic features of Chinese phonology, lexis, syntax and discourse pragmatics, and which is particularly suited for expressing content ideas specific to Chinese culture through such means as transliteration and loan translation.

Similarly, Xu (2010: 1) refers to CE as a developing variety of English, which is subject to ongoing codification and normalization processes. It is based largely on the two major varieties of English, namely British and American English. It is characterized by the transfer of Chinese linguistic and cultural norms at varying levels of language, and it is used primarily by Chinese for intra- and international communication.

The above definitions employ terminology (performancevariety,standard,developing,codification, etc.) that strongly resonates with the WE perspective on non-native Englishes. In fact, most internationally disseminated research on China English is explicitly situated in the WEs paradigm (for example, Bolton 2003; Cheng 1992; Hu 2004; Xu 2010). Although the notion of CE was developed independently of Kachru’s (1986) three circles model of world Englishes, the idea of CE suits the Kachruvian emphasis on the “sociolinguistic realities” which cause English to be different in different contexts (1991: 11).

According to popular taxonomies delineating the features of world Englishes, however, CE remains marginal. It is not an “Outer Circle” English, as that term is reserved for relatively robust non-native varieties which developed in the wake of colonially imposed English and have come to serve many important local functions, particularly in intranational communication. However, to call CE an “Expanding Circle” English, learned only for international communication in limited domains, is not especially accurate, because the highly developed Chinese system of English exams and certificates has great local significance but very little international importance. As Zhao and Campbell (1995: 404) point out, “language is not always for communication”.

The acknowledgement of CE, as Xu (2010: 199) puts it, is “constrained by attitudinal, social, and economic factors”. Xu’s comment suggests a high priority to establish a more explicit positioning of CE in terms of language ideologies and attitudes regarding the global spread of English. As may be evident from the discussion above, English in China may not easily be characterized as simply “ESL” or “EFL,” nor does its rootedness in Chinese society seem to relegate it solely to the “Expanding Circle.” In addition, like many other world Englishes in the “Outer Circle,” CE has been advocated by some linguists but it is not clear how teachers, students, policymakers, users, and other stakeholders might view it. English has enough cultural importance in China that Jiang (2003) is able to convincingly describe “English as a Chinese language.” The unique Chinese context with English playing a major role calls for research to explore whether English is practiced and viewed as a Chinese language by people other than linguists, and what kind of stance (negative, positive, neutral) people take toward this view.

ATTITUDE STUDIES OF CHINA ENGLISH

A review of the literature (Chen and Hu 2006; He and Li 2009; Hu 2004, 2005; Kirkpatrick and Xu 2002) shows an effort in examining attitudes toward CE mostly as a concept rather than its linguistic features. Of the studies that explore attitudes to CE, Kirkpatrick and Xu (2002: 275) deal with the question of whether CE can be “an acceptable standard,” both “politically,” to “Chinese officialdom,” and “socially...among the Chinese themselves”. The authors report on a questionnaire study regarding university students’ attitudes toward language standards for both Chinese and English. The students indicated flexibility with their understanding of standard English, with a large number believing that proficiency in standard English was achievable by non-native speakers. The authors suggest that the questionnaire offers evidence that China English is not socially acceptable, even though it may be somewhat recognized by the students.

Hu published three attitude studies on China English involving students (Hu 2004), Chinese English teachers (Hu 2005) and non-Chinese speakers of English (Chen and Hu 2006). The first study (Hu 2004) involved a large number of students at Three Gorges University and focused on the question of “to what extent Chinese students learning English in China were familiar with the concepts of China English and World English” (2004: 29). The questionnaire responses showed little knowledge of or tolerance for CE among students. Hu (2005) then adapted the same instrument in the second study involving Chinese English teachers. The participants took a more liberal and accepting stance toward CE, leading the researcher to conclude that “a broader more open view of the English language is emerging in China” (2005: 36). The third study (Chen and Hu 2006) involved 21 non-Chinese individuals living in China, most of whom were teachers or business people. Using an acceptability judgment task (AJT), the authors asked a variety of questions about Chinglish and China English and asked participants to respond to sentences with what could be deemed typical features of CE; overall the results suggest that the non-Chinese speakers did not encounter much difficulty when communicating with CE speakers. Chen and Hu (2006) is the only study that has employed an AJT to explore CE, though the sentences that contained typical features of CE were constructed by the researchers rather than taken from a sample of authentic language use.

Investigating the issue from a slightly different angle, He and Li (2009) examined Chinese students’ attitudes toward varieties of English and their preferences for native or non-native teachers. Based on three instruments, “questionnaire survey, matched-guise technique, and group interview” (2009: 75), the researchers reported on responses to a variety of questions about attitudes toward standard English, other varieties of English, China English, and desired pedagogical model for English teaching. Overall, the results of the questionnaire suggest at least partial support by the students and teachers for more incorporation of CE in the English curriculum. However, the matched-guise technique, which exposed the participants to recordings of both CE and standard English, showed that all participants rated standard English much higher in positive characteristics; the authors note that despite this, the participants’ ratings of CE were not overtly negative. Their interview phase, which included 103 participants, found that while most preferred American English as a model, many did not see “standard English” as a necessity, and some believed that features of CE could or should be incorporated even if standard English remained the main model for teaching.

Each of the above studies can be seen as partially bolstering the assertion that there is a small but growing trend toward accepting localization, or “Chinese characteristics” in English in China, which suggests that CE is indeed developing. Importantly, the studies were for the most part situated in the domain of education. Only Chen and Hu (2006), differing from other studies which simply asked participants to express a judgment toward CE as a concept, connected linguistic features and attitudes by using the acceptability judgment task (AJT). AJTs have roots in theoretical linguistics, and in their most basic form, involve “explicitly asking speakers whether a particular string of words is a well-formed utterance of their language” (Schütze 2011: 349). The spread of AJTs to world Englishes research, however, is relatively recent (e.g. Bokhorst-Hengetal. 2007; Chen and Hu 2006; Higgins 2003; Mollin 2005; Rubdyetal. 2011). Historically, AJTs have been carried out using decontextualized sentences. In the case of theoretical linguistics, scholars purposely create unusual or grammatically confusing sentences in order to get a better sense of participants’ innate grammatical intuitions. In WEs, AJTs have tended to use sentences of stereotyped or potentially typical local Englishes to elicit attitudes (for example, Mollin’s 2005 study of Euro-Englishes employs sentences which are not necessarily taken from attested samples of authentic language). Surprisingly, very few studies have endeavored to investigate the question of nativized local varieties in authentic texts. Two older WE studies (Gupta 1988; Parasher 1983) employed an AJT-like task, but did not describe their methods as an AJT. Both studies involved professional linguists rather than educated speakers or learners of English.

Like most AJT studies, Chen and Hu’s (2006) sample texts were not necessarily drawn from authentic usage. They used examples like “Is this seat empty?” and “I’m a public servant” (2006: 235), which might be typical of certain Chinese speaking patterns, but are not necessarily nonstandard or viewed as “Chinese” in other English varieties. Thus, while Chen and Hu convincingly claimed that the results of their study pointed to the acceptance of CE by the participants, the lack of explanation of the items on their questionnaire underscores the need for more articulation between features-based studies and studies in which participants expressed attitudes toward or judgments of actual samples of English used in China. Given the paramount importance of “acceptance” (of both particular linguistic variations and varieties of English as a whole) in WE, it would be prudent to study CE by adopting AJTs with authentic language-in-use.

UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC WRITING AS A DOMIAN FOR CE RESEARCH

One source of authentic language-in-use which has been largely ignored in studies on CE and other world Englishes research is academic writing by university students. In general, there is a greater need to pay attention to the role of English academic writing in the shaping of local and global currents of English in the era of globalization. Mostly importantly, the ever-internationalizing domain of college writing is especially important as a “global education contact zone” (Shi 2009: 60). If English is nativizing in China, we should expect the domain of education to be first and foremost among the sites where this nativization takes place. This is particularly true at the tertiary level, where elite students in a variety of subjects are taught in English, English teachers are trained, and assessment decisions about what constitute acceptable levels of proficiency and even acceptable uses of English are made.

English looms large in education in China, being a compulsory subject from grade three through the second year of university for all students. In light of the important place of English in Chinese education and society, it would be prudent to include academic English from (advanced) students in any investigation of CE, though some have argued against this. Pang (2006), in his proposal for a corpus of China English, suggested limiting such a corpus to “include texts that are published in Chinese official publications (journals, magazines, newspapers, books, CD-ROMs or broadcast through radios or TV channels),” arguing that “English texts written by English learners at various levels at different schools, universities or training institutions do not fit the criterion” (2006: 67). It is not clear to us why this should be, since education for English majors in China aims at “developing students’ language proficiency to an advanced/sophisticated level” (Wang 2006), and university-educated Chinese are considered to be the “key users and shapers of Chinese English” (You 2011). Unlike Pang (2006), Xu (2010) agued for including the English of both students in their later years of university as well as graduate students in CE studies (67-68). Similarly, Ma (2012) demonstrated how degrees of acceptability in some Chinese students’ English writing might indicate a line to be drawn between interlanguage (learner’s errors) and the emerging Chinese variety of English. Together with Xu (2010) and Ma (2012), we believe that there is a compelling reason not to dismiss the language of Chinese university students—especially English majors—as mere learner English; it is particularly relevant to the Chinese context and should be considered in CE research. We feel confident that university students’ academic English writing is an important site for investigating features of and attitudes toward English usage in the Chinese context—that is, a site for investigating whether CE is developing, and if so, how.

THE PRESENT STUDY

The above literature review suggests a need for more research on a connection between general attitude studies and linguistic and acceptability judgments of CE in context. In this direction, the present study elicits Chinese teachers’ reactions to nonstandard usage in Chinese students’ English writing and their reasons for doing so as well as their (non)acceptance of CE. The data reported here is from a larger study which investigates acceptability judgments of both Chinese and non-Chinese English teachers using samples of academic writing by Chinese university students. Our goal is to approach academic writing in the Chinese context as a site where attitudes toward nonstandard usage can be investigated as evidence of whether (and/or how) a nativization process (Kachru 1992) or sense of “ownership” of English (Higgins 2003) is taking place in China. For the purposes of this paper, we are focusing on two guiding research questions:

1. How do the participating Chinese teachers describe features of the text as being particularity “Chinese”?

2. How do participating Chinese teachers’ acceptance or non-acceptance of certain features of the text contribute to an understanding of the features of CE?

Method

Participants

This study, as part of a larger study still ongoing, involves 30 native Chinese-speaking English teachers from three higher education institutions in China (with pseudonyms of SIC, NKU, and ATC). The institutions were chosen as they represent different types of tertiary education in the Chinese system. SIC is a small independent college, a relatively new type of higher education institution in China, which is privately funded but is connected to and shares resources with a local public university. SIC is on the campus of a local provincial university and enrolls approximately 8,000 students. The foreign language department enrolls nearly 1,000 students, many of whom are English majors. Different from SIC, NKU is one of China’s larger universities (it enrolls over 50,000 undergraduate and graduate students), and is one of an elite group of universities under the direct supervision of the Chinese ministry of education (formerly known as “National Key Universities”). It is consistently ranked among the top Chinese universities, and all of its faculty members are required to have masters’ or PhD degrees. The third participating institution, ATC, is a technical college affiliated with NKU, enrolling approximately 10,000 students. All deans and several professors are drawn from the faculty of NKU and students are awarded NKU degrees. However, ATC is located in a different city and has fewer resources than NKU.

Participants from the three institutions were recruited initially via an email to department heads at the respective sites, and later attending department meetings to introduce the project by the first author. After some initial participants expressed interest, snowball sampling was used and earlier participants assisted in recruiting others in their departments. Participants who completed only the AJT were given a 100yuangift card to a local supermarket, while those who also volunteered to participate in interviews were given 150yuangift cards. Participants were asked to spend no more than 90 minutes on the AJT, and interviews lasted 40 to 60 minutes. For confidentiality, we assigned each participant an ID (8 from SIC, SIC1-8; 11 from NKU, NKU9-19; and 11 from ATC, ATC20-30). Although the participants vary in their teaching experiences (ranging from 3 to 27 years), the majority were female (21/30), in their 30s (24/30), and have an MA (25/30) in Applied Linguistics or English (18/30).

AJTandfollow-upinterview

The AJT comprises seven essays written by fourth-year English majors from Chinese universities (See the task and one of the essays in the Appendix). The essays were selected by the first author from a larger corpus of student writing (Wenetal. 2008) based on their relative lack of major spelling and grammatical errors that could be distractive from the AJT task. The participants were instructed to read each essay to identify any lexical or grammatical “chunk” of text they deemed unacceptable at the sentence level for any reason, including grammar, syntax, style, word choice, appropriateness and so on, with a limit of ten “chunks” per essay. Some participants exceeded the limit, whereas others commented on less than ten chunks per essay. There were a total of 1,749 comments made on the 7 essays, or an average of roughly 8 comments per participant per essay.

We also conducted follow-up interviews with 15 of the participants to explore reasons for their judgments of unacceptability and also about their general attitudes toward China English. By adopting a broader definition of acceptability for this task, we hope to be able to gain more insight into the reasons that these teachers give for making judgments about whether students’ potentially nonstandard usage is accepted or not, and to eventually, in the larger study, compare their judgments with non-Chinese English teachers.

Dataanalysis

To identify the way that participants described features of the text as being particularity “Chinese,” we read participants’ comments repeatedly focusing on terms such as “Chinglish” or “Chinese English.” All comments and their related chunks were exported from Microsoft Word documents to an Excel spreadsheet, where a filter was applied to display only comments including the words “Chinese” or “Chinglish.” A total of 58 mentions of “Chinese” or “Chinglish” were identified in participants’ comments on 47 chunks of texts. We looked at each comment in which participants identified a chunk as being “Chinese” or “Chinglish,” to (a) explore the attitude the commenter took toward the perceived Chineseness of the chunk, (b) identify the lexical or grammatical feature the commenter was identifying in the chunk, and (c) examine which of the chunks identified as “Chinese/Chinglish” were more likely to be rejected, and which went largely uncommented on, by other participants.

Findings

Howdoparticipantsdescribefeaturesofthetextasbeingparticularity“Chinese” ?

Of the 58 mentions of Chineseness of the writers’ English, 22 used the term “Chinglish,” while 36 used the term “Chinese.” Of the 22 “Chinglish” comments, six simply commented that the chunk was Chinglish (e.g. “This is Chinglish,” or simply a one-word comment, “Chinglish”), and 14 offered a suggestion for an alternative to the perceived Chinglish. In the remaining two, one commenter simply stated that “many Chinese students prefer this statement which is rare in English” without offering a suggestion, and the other guessed the writer’s meaning (“what he/she meant, I think, is...”) but did not offer a correction. All of these comments evinced a negative attitude toward “Chinglish” as being a marked and dispreferred aspect of the text. Similarly to the “Chinglish” comments, 10 of 36 “Chinese” comments suggested corrections, while the others simply made reference in some way to the usage being typical of Chinese writers. In some cases this was directly referred to as an error (e.g. “it is the common mistake by Chinese students”), while in others cases, it was believed to be simply “influenced by Chinese.”

One commenter (NKU17), whom we call Lin in this paper, made a larger number of comments mentioning Chinglish or Chinese; 14 of her 53 comments (about 26%) mentioned Chinese, Chinglish or Chinese English. Together, Lin’s comments seemed to negate the possibility of an acceptable Chinese variety of English, or the legitimacy of the writer using potential innovations. In some comments, for example, Lin stated there was “no such saying” or “no such phrase” in English. While showing confidence in her own English ability, Lin positioned the student writers as Chinese who are “not used to English.” When asked what she meant by “not used to English” during the follow-up interview, Lin explained:

Lin: They have read many articles in textbooks, but it’s only poor articles, poor English. They spend a lot of time doing exercises, multiple choices. So about articles, passages, good English—they have never met good English.

Researcher: ...So in other words...they’re not familiar with, as you say, good English.

Lin: He can express this meaning in other ways. We should say this is not good English; this is bad English, right? He can use fluent ways and other elegant ways to express the meaning, but he doesn’t know. He just translates the Chinese thinking into English. Only simple words. He can only use limited vocabulary, right?

Later in the interview, the first author asked Lin whether the expressions to which she responded with such comments as “no such phrase” or “no such saying” could be considered “creative” rather than errors. Lin responded by citing an elder professor, who stated that students should not have creativity in English learning, though they should have creativity in science. Lin believed that the nonstandardisms or mistakes in the essays were indicative of the larger trend of student writers focusing on passing exams. As she put it,

They don’t have a sense of the language. They have a sense of exercises. This is preventing them from learning English a lot.... One of my teachers in my postgraduate program once said, the science majors can get high points in the GRE and TOEFL, but once they are required to write something, they show their [true selves]. Writing is quite revealing.

Lin’s comments suggest that it was not necessarily the “mistakes” which she viewed as problematic in the students’ writing, but a lack of sophistication or elegance which she stated was a result of being exposed only to textbook English and learning to take exams rather than learning practices such as “picking out interesting articles to read aloud” or “copy[ing] wonderful paragraphs and read[ing] them often.”

Like Lin, another participant (SIC5), whom we call Mao in this paper, discussed his views about nonstandard or Chinese-influenced uses of English in China at length during the interview. However, unlike Lin, Mao believed that some Chinese-influenced English should be acceptable with the following example from his own experience:

Let me tell you a very interesting experience of mine. ...there is a translation work, ..., and one word, a Chinese word, ismingpian(名片). ...I literally put it on the paper ‘name card’ [and] I think it is acceptable. But later, ...the teacher told me...that this translation was wrong-mingpianactually should be calling card, visiting card, so I feel-oh, I felt enlightened at that time. But later, I found myself a part-time job, and my boss was from America. She also had an interview with me. After the interview, she thought that I was qualified; therefore, she gave me her...card and she said, “this is mynamecard.” So I felt very interesting, because “name card,” we Chinese, we think it is unacceptable: it’s Chinese English, Chinglish, or in Shanghai, we say 洋泾浜英语,but you see even an American think it is OK. Maybe when in Rome they do just as the Romans do or something, but in my opinion, name card, this word will not cause any misunderstanding, therefore from my perspective, from my point of view, I think this is still acceptable.

However, in the case of writing, Mao stated that he was not able to put into practice his beliefs about the acceptability of CE. When the topic of the interview shifted to the acceptability of Chinese English in academic writing, he said:

You see, although I myself adopt a tolerable view on this point, but almost all of my students need to take this or that kind of test, and in the test, these kinds of mistakes will not be tolerated. Therefore as a teacher, if they hand in their composition full of such kind of grammatical mistakes, it’s my responsibility—the responsibility lies with me to correct them. I cannot be so tolerable as I want myself to be. So I have to do it.

While Lin and Mao held very different views about the acceptability of CE as an abstract entity, they both regarded the acceptability of particular nonstandard or usages as impractical for the main purpose of academic writing in China, which was to pass English exams. Lin argued that because English was viewed as a utilitarian tool for passing exams, it could not be considered an independent variety in China:

...they just pass (the) exam and then forget it. So how come there should be a variety of English for them? They don’t have time, the chance to use their Chinglish.... If Chinglish is a form, it only exists in exams.

Lin’s comment suggests that the Chineseness of English in China is not only a linguistic phenomenon (as in the comments related to the Chinese language), but also as an educational one. According to Lin, the exam-oriented and utilitarian motives of English-using students and teachers were enough to preclude any possibility of CE existing in the traditional sense of a variety of English.

Howdoparticipants’acceptanceornon-acceptanceofcertainfeaturesofthetextcontributetoanunderstandingofthefeaturesofCE?

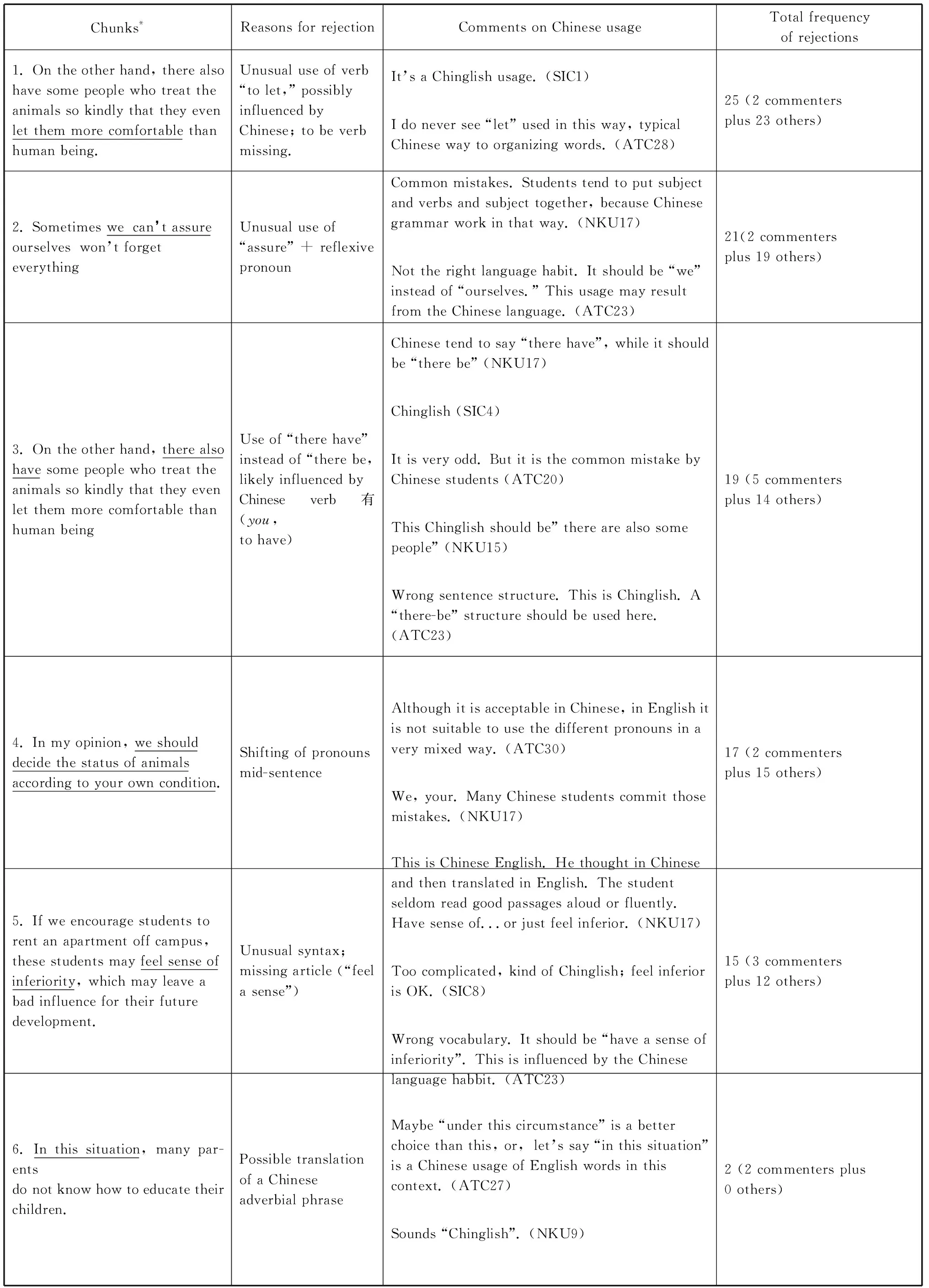

To answer the second research question, we looked at the frequencies of chunks that were recognized as “Chinese/Chinglish” and rejected by participants. The frequency order based on the number of rejections suggests a continuum moving from chunks that are clearly identifiable as being influenced by Chinese grammar to those which are less obviously traceable to Chinese language influence. The former are more likely to be rejected whereas the latter are likely to be accepted. Table 1 shows six examples of chunks identified as “Chinese/Chinglish” by at least two participants and in the order from the most to the least rejections received. The first example has a total frequency of 25 rejections, meaning 23 participants, apart from the two commenters who mentioned “Chinese/Chinglish when rejecting the chunk, also made rejections without explicitly labeling the relevant chunk as “Chinese/Chinglish.” In contrast, the last example has a frequency of two rejections, meaning no other participants except the two commenters made the rejection.

The six examples highlight participants’ perceptions of Chinese influence in each chunk. The first two chunks (“let them more comfortable” and “we can’t assure ourselves...”) could be literally translated from Chinese (让他们更舒服;我们不能肯定自己……). They were, therefore, recognized as Chinglish or a common mistake made by Chinese students and were rejected by 25 and 21 participants, respectively. The third and fourth examples contain the nonstandard use of a verb (“have”) and pronouns shifted in the same sentence, and a total of 19 and 17 participants considered them unacceptable, respectively. The slight drop in the frequency of rejections suggests that although the third and fourth examples were still considered “Chinese” by some participants (especially “there have,” a chunk labeled Chinese/Chinglish by five participants), they are on the whole less stigmatized usages than the first two. The fifth example, involving the phrase “feel sense of,” was labeled as Chinese/Chinglish by three commenters, but was only rejected by half of the participants (15/30). We believe that since this chunk was not rejected by the other half of the participants, it is also less stigmatized. This may be in part because the practice of not including an article (“feel sense of”) where it would be included in standard English (“feel a sense of”) has less obvious, direct “Chinese” influence. Finally, the last chunk, “in this situation,” is a standard English phrase on its own, but somehow sounded Chinese in the given sentence to only two participants. To illustrate how the rejection rate is related to the degree perceived of linguistic influence from Chinese, we will further compare the first and last example.

Table 1: Reasons, comments and frequencies of rejections for six chunks

Note:Relatedchunksarehighlightedandunderlined.

The first example is the word “let,” which was labeled as an unacceptable Chinese/Chinglish usage by two commenters and rejected by a total of 25 (83%) of the participants. Linguistically, it is most likely that the writer’s use of the word in “let them more comfortable” is related to the Chinese word 让 (ràng), which could be translated as “make” or “allow.” If the sentence were changed to “make them more comfortable,” which would be standard, it is unlikely that any commenter would flag the chunk as unacceptable.

Since we wish to investigate these chunks as evincing possible features of CE, a possible hypothesis is that this use of “let” could fall under the definition of CE lexis undergoing semantic shift, which is identified by several scholars as a feature of CE (see Cheng 1992; Gao 2001; Xu 2010; Yang 2006). This use of “let” could be subject to what Xu refers to as a “semantic change,” for example in the use of the word “open” in CE where “turn on” (a light or appliance) would be used in American or British English. Given this possible application of semantic shift to “let,” we, however, found that 25 of the 30 participants marked it as unacceptable though the reasons for their judgments varied. Many appeared to rely on intuition in comments including “‘let’ feels wrong,” “not a proper word,” “Let is not used in this way,” “‘let them more comfortable sounds weird,’” and so on. The overwhelming rejection of this use of “let” suggests that a semantic shift in this lexical item is unlikely to be accepted by Chinese speakers and therefore is not a likely candidate for CE. It is likely to remain marked and to be rejected by most Chinese English speakers as a stigmatized “Chinglish” phrase rather than an acceptable semantic shift.

The final entry in Table 1 offers an example from the other end of the spectrum. Like “let,” “in this situation” was also labeled “Chinese” or “Chinglish” by two commenters. This phrase is not seen as nonstandard by either of the authors of this study in this context, but it is possible that the commenters viewed “in this situation” as an inappropriate translation of the Chinese adverbial phrase “在这种情况下.” However, the degree to which “in this situation” is an imperfect translation, or one which is more likely to be stigmatized as “Chinglish,” is unclear. For example, the China National Knowledge Infrastructure, a popular academic repository in China, suggests translating “在这种情况 下” as “in this situation” on its “Translation Assistant” page, offering numerous examples of translated Chinese-English texts using this expression (Dict.cnki.net 2008). However, a popular online Chinese-English dictionary (Dict.cn) created by Chinese students studying in the US offers examples such as “in such a case,” “under these circumstances,” and “in this instance” (Dict.cn 2012). Thus, CNKI, which is based in China, shows a preference for “in this situation,” while Dict.cn, which is primarily designed for Chinese abroad, does not even include “in this situation.” (For more on the use of Internet usage to check acceptability, see Li 2010.)

We suggest that because “in this situation” is labeled as Chinese/Chinglish by some participants but not rejected by the vast majority of the participants, it is more likely as a candidate for CE. It is possible that “in this situation,” a standard English phrase being used by the Chinese students in cases where other phrases would be used by people outside China, could be considered a part of the “expanding circle of CE lexis” (Xu 2010: 33), or common standard English words also included in CE. At the very least, the acceptance of this allegedly Chinese/Chinglish chunk suggests that when Chinese language influence is not obvious, readers are more likely to accept the phrase—even if it does turn out to be preferred more by Chinese English speakers than by inner circle English speakers, the possibility of which needs to be investigated further. The phrase “in this situation” in the sentence-initial position does occur in seven other essays in the corpus from which we drew the essays for this study. Knowing this, a next step could be to look more specifically into this phrase across corpora of English writing from China and other settings, and compare Chinese English speakers’ acceptability judgments with non-Chinese judgments to reveal more about the status of this usage.

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATION FOR FURTHER ANALYSES

The analyses described above offer an example of the use of an acceptability judgment task in a world Englishes framework for studying attitudes toward non-native usages of English in writing. This method has allowed us to progress in a “bottom-up” fashion, using authentic language and reactions rather than relying on preconceptions about the influence of Chinese on CE. While the present study is still in progress, the data so far suggest that English usage which was perceived as clearly influenced by the Chinese language or literally translated from Chinese (e.g. “let them more comfortable”) was likely to be rejected. It was also possible that a negative conception of CE, as in the case of the commenter Lin, made a participant more likely to label chunks as Chinglish. We also found that those chunks which were most obviously related to Chinese influence or most commonly seen as Chinglish errors (e.g. “there also have”) were likely to be rejected by readers. We speculate that as the total numbers of commenters rejecting a chunk decreases, it is possible that the relevant chunk is a potential candidate for “acceptable” CE, though further investigation and triangulation is necessary.

The fact that not all participants have agreed on the judgments of acceptance on chunks of students’ writing might be evidence that CE is not nativized, or that what constitutes the “Chinenesness” of CE is not well-established. You (2008: 247) asserts that “the interaction between elements, structures, and rules of both Chinese and English and the Chinese discursive and cultural context may generate new, hybrid linguistic and rhetorical features that can hardly be labeled as traditional Chinese” and that “context and the user” are of utmost importance in CE (2008: 248). The influence of the Chinese language, while arguably an important factor in describing CE and attitudes toward it, is only part of the story when it comes to understanding how English is used in China and what people’s judgments, perceptions, and attitudes about it are. We will continue to investigate the relationship of acceptance of CE to acceptance or rejection of particular lexical or grammatical features, and to explore the possibility of commenters noticing what could be called “false Chinglish,” or expressions which might not be related to Chinese influence. In addition, there are further insights to be drawn by examining sections of the texts that werenotmarked as unacceptable.

We suggest that future studies should employ AJTs with more authentic texts from a variety of academic sources of Chinese English, including papers written for content courses, academic journals, theses, dissertations, abstracts, and monographs. AJTs could also be used with texts from other domains, including blogs, websites, newspapers, and magazines. In addition, the involvement of native English speakers and English speakers from outer circle and expanding circle countries would allow for comparison and more insight into whether possible CE features are accepted or rejected by English speakers outside of China. Finally, participants’ comments could be analyzed in terms of their stance toward both standard English and CE, or their indexing of feelings of “ownership” of English (cf. Higgins 2003). The use of AJTs with authentic texts and the comments and discourse they can generate offers a powerful tool for researchers interested in CE, academic writing, and English in many other contexts.

APPENDIX: ACCEPTABILITY JUDGMENT TASK INSTRUCTIONS AND SAMPLE ESSAY

Instructions

The purpose of the project is to learn about your perception of acceptable features of written English.

The following seven essays were written by English majors in their fourth year of university in a non-English-speaking country. Each essay was written in response to a different prompt, which is also provided, and the essays are final drafts which the students submitted to their teachers. You will be asked to identify any usage in the essays which you consider to be unacceptable in this context.

Please read each essay, and using Microsoft Word’s comments features, select any word, phrase, or arrangement of words which you consider unacceptable. In order to save time, please limit yourself to selecting a maximum of ten instances which you believe to be the most unacceptable for each essay. The whole task should take you no more than 90 minutes.

After you have selected a part of the text, please explain in your comment why you identified that part as unacceptable. You can explain your reasoning in as much or as little detail as you want.

For example, if you saw this passage:

As we all know, no one is perfect. No one can handle all the things around us, and cooperation can let people work better and more quickly.

You might make the following comments for the highlighted words:

As we all know, no one is perfect. No one can handle all the things around us, and cooperation can let people work better and more quickly.

Comment 1: “All the things” is an unusual phrase. “Everything” is more appropriate choice.

Comment 2: I have never heard “let” used in this way.

Please note: your goal is not necessarily to find and correct errors. The important thing is to express your opinion about the “acceptability” of the English used by the writers. There are no right or wrong choices.

Finally, please limit your comments to these lexical (vocabulary, word choice, phrases, etc.) and syntactic (grammar, phrases, word order, sentence structure, etc.) features, but do not comment on the overall rhetorical or discourse features of the text. (For example, comments such as “this conclusion is unclear” or “this essay has no thesis statement” are not related to the questions under investigation in this study.)

Thank you again for your participation in this project. Please feel free to contact me with any questions.

A Sample text:

Prompt B*: Some people think that the animals should be treated as pets, while others think that animals are resources of food and clothing. What is your opinion?

There are many animals around us. Some people raise animals as their pets, even their children. But some people eat them, or use them to make something. Yet what are they in your opinion to the end? This topic sounds a little boring. If I must have a decision, I have to take the middle-of-the-road line.

In my opinion, the status of the animals is difficult to be decided, because we can neither treat them as pets only, nor just use them to satisfy us. On the one hand, in the past, we think that we are the masters of the earth, so we polluted the environment discretionarily and took advantage of the resources improperly. Animals were also harmed. Many animals had disappeared. But the fact tells us that we are wrong. Therefore, animals are not just the resources of our living. On the other hand, there also have some people who treat the animals so kindly that they even let them more comfortable than human being. We can find lots of news about this from TV and newspapers. To be frank, I think it is stupid to do this. We can treat them as friends, but not children or families. If all of us raise animals in this way, what our society will be.

In my opinion, we should decide the status of animals according to your own condition. If you are fond of them and like to raise one, you can feed one, play with it and treat it as your own lovely pet. But you should have a limit. Don’t cocker it so much. It is just an animal after all.

If you think that they are heartless, dirty and ugly, you can treat them just as animals. You can eat them, wear the clothes which are made from them, and use them to make things. But you should also have a limitation. The earth is ours, so is theirs. Don’t kill them arbitrarily, because the balance of the nature needs them. Moreover, they are the most important resources of our food and clothing, so the nature and our life both need them. We should take advantage of animals continually.

In conclusion, we can treat the animals as pets or, the resources of food and clothing freely from case to case. However don’t forget the limitations. If all of us can do like this, I think it’s all right.

*This essay, like all others in the AJT, is a part of the corpus collected by Wenetal. (2008).

REFERENCES

Bokhorst-Heng, W.D., L. Alsagoff, S. McKay, and R. Rubdy. 2007. ‘English language ownership among Singaporean Malays: Going beyond the NS/NNS dichotomy,’WorldEnglishes26: 424-45.

Bolton, K. 2003.ChineseEnglishes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chen, M. and X. Hu. 2006. ‘Towards the acceptability of China English at home and abroad,’EnglishToday22/4: 44-52.

Cheng, C. 1992. ‘Chinese varieties of English’ in B. B. Kachru (ed.):TheOtherTongue:EnglishAcrossCultures. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, pp. 162-77.

Dict.cn. 2012. ‘在这种情况,’ available at dict.cn/在这种情况.

Dict.cnki.net. 2008. ‘在这种情况,’ available at dict.cnki.net/dict_result.aspx?searchword=在这种情况&style=&tjType=sentence.

Gao, L. 2001. ‘The lexical acculturation of English in the Chinese context,’StudiesintheLinguisticSciences31: 73-78.

Ge, C. 1980. ‘Random thoughts on some problems in Chinese-English translation,’FanyiTongxun2:1-8.

Gupta, A. F. 1988. ‘A standard for written Singapore English?’ in J. Foley (ed.):NewEnglishes:TheCaseofSingapore. Singapore: Singapore University Press, pp. 27-50.

He, D. and Li, D. C. S. 2009. ‘Language attitudes and linguistic features in the ‘China English debate,’WorldEnglishes28:70-89.

Higgins, C. 2003. ‘“Ownership” of English in the outer circle: An alternative to the NS-NNS dichotomy,’TESOLQuarterly37: 615-44.

Hu. X. 2004. ‘Why China English should stand alongside British, American, and the other “world Englishes”,’EnglishToday20: 26-33.

Hu, X. 2005. ‘China English, at home and in the world,’EnglishToday21/3: 27-38.

Jiang, Y. 2003. ‘English as a Chinese language,’EnglishToday19/2: 3-8.

Kachru, B. B. 1986.TheAlchemyofEnglish:TheSpread,Functions,andModelsofNon-nativeEnglishes. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Kachru, B. B. 1991. ‘Liberation linguistics and the Quirk concer,’EnglishToday7/1:3-13.

Kachru, B. B. 1992.TheOtherTongue:EnglishAcrossCultures. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Kirkpatrick, A. and Xu, Z. 2002. ‘Chinese pragmatic norms and “China English”,’WorldEnglishes21: 369-79.

Li, D. C. S. 2007. ‘Researching and teaching China and Hong Kong English,’EnglishToday23/3&4: 11-17.

Li, D. C. S. 2010. ‘When does an unconventional form become an innovation?’ in A. Kirkpatrick (ed.):RoutledgeHandbookofWorldEnglishes. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 617-33.

Ma, Q. 2012. ‘Upholding standards of academic writing of Chinese students in China English,’ChangingEnglish:StudiesinCultureandEducation19: 349-57.

McArthur, T. 1998.TheEnglishLanguages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mollin, S. 2005.Euro-English:AssessingVarietyStatus. Tübingen, Germany: Gunter Narr.

Pang, P. 2006. ‘A proposal for national corpus of China English,’ChinaEnglishLanguageEducationAssociationJournal29/1: 66-70.

Parasher, S. V. 1983. ‘Indian English: Certain grammatical, lexical and stylistic features,’EnglishWorld-Wide4/1: 27-42.

Rubdy, R., S. McKay, L. Alsagoff, and W. Bokhorst-Heng. 2008. ‘Enacting English language ownership in the Outer Circle: A study of Singaporean Indians’ orientations to English norms,’WorldEnglishes27: 40-67.

Schütze, C. 2011. ‘Grammaticality judgments’ in P. Hogan (ed.):TheCambridgeEncyclopediaoftheLanguageSciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 349-50.

Shi, L. 2009. ‘Chinese-Western “contact zone”: Student resistance and teacher adaption to local needs,’TESLCanadaJournal27: 47-63.

Wang, H. 2006.AnimplementationstudyoftheEnglishasaforeignlanguagecurriculumpoliciesintheChinesetertiarycontext. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Queen’s University.

Wen, Q., M. Liang, and X. Yan. 2008.SpokenandWrittenEnglishCorpusofChineseLearners2.0. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

Xu, Z. 2010.ChineseEnglish:FeaturesandImplications. Hongkong: Open University of Hong Kong Press.

Yang, J. 2006. ‘Learners and users of English in China,’EnglishToday22/2: 2-10.

You, X. 2008. ‘Rhetorical strategies, electronic media, and China English,’WorldEnglishes27: 233-49.

You, X. 2010.WritingintheDevil’sTongue:AHistoryofEnglishCompositioninChina. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

You, X. 2011. ‘Chinese white-collar workers and multilingual creativity in the diaspora,’WorldEnglishes30: 409-27.

Zhao, Y. and K. P. Campbell. 1995. ‘English in China,’WorldEnglishes14: 391-404.

NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS

ShaofengLireceived his Ph.D. in Second Language Studies from Michigan State University in 2010. He is currently Lecturer of Applied Language Studies at the University of Auckland, where he teaches postgraduate and undergraduate courses in second language acquisition. His primary interest is in investigating the interactions between learning conditions (e.g. implicit vs. explicit; task type) and individual difference variables such as language aptitude and working memory. His other research interests include form-focused instruction, quantitative research methods, and language testing. 〈s.Li@auckland.an.nz〉

RodEllisis currently Professor in the Department of Applied Language Studies and Linguistics, University of Auckland, where he teaches postgraduate courses on second language acquisition, individual differences in language learning and task-based teaching. He is also a professor in the MA in TESOL program in Anaheim University and a visiting professor at Shanghai International Studies University (SISU) as part of China’s Chang Jiang Scholars Program. His published work includes articles and books on second language acquisition, language teaching and teacher education. His latest book (2012) isLanguageTeachingResearchandLanguagePedagogy(Wiley/Blackwell). He is also currently editor of the journalLanguageTeachingResearch.

NatsukoShintaniis Assistant Professor in English Language and Literature at the National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. She obtained her Ph.D. in Language Teaching and Learning from the University of Auckland in 2011. Her research interests encompass roles of interaction in second language acquisition. She has also worked on several meta-analytic studies. She has published articles inStudiesinSecondLanguageAcquisition,LanguageTeachingResearch,RELCJournalandLanguageLearning, and is currently working on a book for John Benjamins.

MinWangis currently an Associate Professor at the Department of Human Development and Quantitative Methodology at the University of Maryland, College Park. She received her Ph.D. in Applied Cognitive Science from the University of Toronto in 2000. Upon graduation she completed her two-year post-doctoral training at the Learning Research and Development Center, University of Pittsburgh. She became a member of the Faculty of Human Development at the University of Maryland in 2002. Dr. Wang’s research interests are in the area of language and reading development. Her work has mainly focused on second language, bilingual and biliteracy development, funded by NIH/NICHD, NSF, and Spencer Foundation over the past ten years. Dr. Wang is currently serving on the editorial boards ofAppliedPsycholinguistics,WritingSystemsResearchandContemporaryEducationalPsychology; she is also the current convener of the Educational Psychology Program in her department. 〈minwang@umd.edu〉

ChuchuLiis currently a third-year doctoral student at the Department of Human Development and Quantitative Methodology at the University of Maryland, College Park (UMCP). She received her B.S. in Psychology from Beijing Normal University (BNU). During the time in BNU, she worked as a research assistant in the University’s Brain and Second Language Learning Lab and Brain and Chinese Cognition Lab. Her research interests include phonological processing and the interaction between orthographic and phonological knowledge in word recognition among both monolingual and bilingual speakers.

DilinLiureceived his Ph.D. in English from Oklahoma State University in 1992. He is currently Professor and Coordinator of the Applied Linguistics/TESOL program in the Department of English at the University of Alabama. His research and publications focus on grammar and vocabulary, especially corpus-based, cognitive linguistics-inspired description and teaching of grammar and vocabulary. Liu has been a member of the Editorial Advisory Boards ofEnglishLanguageTeachingJournal(2001-2004),TESOLQuarterly(2005-2008),ReflectionsonEnglishLanguageTeaching(2006-present), andTESOLJournal(2009-present), and a reviewer for over a dozen journals in applied linguistics and linguistics. 〈dliu@as.ua.edu〉

HanLuois a lecturer of Chinese at Northwestern University. She received a Ph.D. in foreign language education from the University of Texas at Austin in 2011, and a Ph.D. in linguistics and applied linguistics from Beijing Foreign Studies University in 2007. Her research interests include cognitive linguistics, second language acquisition, foreign language anxiety, and teaching Chinese/English as a foreign language. 〈han.luo@northwestern.edu〉

YanLiis an Assistant professor in the department of East Asian Languages and Cultures at the University of Kansas. She received her Ph.D. in Second language Acquisition from the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures at the University of Southern California in 2008. Research interests include Chinese linguistics, second language acquisition and research on teaching Chinese as a foreign language. 〈yanli@ku.edu〉

LingShiis a professor in the Department of Language and Literacy Education at University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. Previously she taught in universities in Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Toronto. She obtained her Ph.D. in 1996 from Ontario Institute of Education, University of Toronto. Her research focuses on Second Language Writing, English for Academic Purposes, and Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language. 〈ling.shi@ubc.ca〉

JoelHengHartseis a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Language and Literacy Education at the University of British Columbia. He has taught English at several Chinese universities and in the UBC-Ritsumeikan University Academic Exchange Program. His research focuses on world Englishes, second language writing, and language in society.

YiXuis an Assistant Professor of Chinese Language and Linguistics at the University of Pittsburgh. She received her Ph.D. in Second Language Acquisition and Teaching at the University of Arizona. She is interested in generative approaches of second language acquisition of syntax and using psycholinguistic methods in SLA researches of sentence processing and character reading. She also maintains a broad interest in corpus linguistics, Chinese functional grammar, and CFL pedagogy. 〈xuyi@pitt.edu〉

NanJiangreceived his Ph.D. from the Interdisciplinary Ph.D. Program in Second Language Acquisition and Teaching at the University of Arizona in 1998. He is currently an associate professor in the Second Language Acquisition Program at the University of Maryland. His research mostly deals with psycholinguistic study of second language acquisition and processing, with a focus on lexical, morphological, and semantic development and representation in adult L2 learners. His recent book on conducting reaction time research in second language studies was published by Routledge in December, 2011. 〈njiang@umd.edu〉

- 当代外语研究的其它文章

- PHONOLOGICAL PERCEPTION AND PROCESSING IN A SECONDLANGUAGE

- DOING META-ANALYSIS IN SLA: PRACTICES, CHOICES, ANDSTANDARDS

- SOURCES OF FOREIGN LANGUAGE ANXIETY: TOWARDS AFOUR-DIMENSION MODEL

- AUTOMATICITY IN A SECOND LANGUAGE: DEFINITION, IMPORTANCE,AND ASSESSMENT

- ON PSYCHOLINGUISTIC AND ACQUISITION STUDIES OF RELATIVE CLAUSES:AN INTERDISCIPLINARY AND CROSS-LINGUISTIC PERSPECTIVE

- COMBINING COGNITIVE AND CORPUS LINGUISTIC APPROACHES IN LANGUAGE RESEARCH AND TEACHING:THEORETICAL GROUNDING,PRACTICES,AND CHALLENGES