COMBINING COGNITIVE AND CORPUS LINGUISTIC APPROACHES IN LANGUAGE RESEARCH AND TEACHING:THEORETICAL GROUNDING,PRACTICES,AND CHALLENGES

DILIN LIU

University of Alabama

E-mail:dliu@as.ua.edu

INTRODUCTION

In the past two decades,Cognitive Linguistics(CGL)and corpus linguistics(CPL)have emerged as arguably the two most influential contemporary linguistic theories/approaches in the research on language use and language teaching,1as is evidenced by the plethora of informative studies in applied linguistics that have been based on one or the other(e.g.for CGL-based studies:Boers 2000;Boers and Lindstromberg 2008;Holme 2009;Kövecses and Szabó1996;Pütz et al.2001;Robinson and Ellis 2008;Tyler 2012;and for CPL-based studies:Aston 2001;Bider et al.1998;Hunston and Francis 1998,2000;Liu 2008a,2008b,2010a,2010b,2011a;2011b,2012;Liu and Espino 2012;Liu and Jiang 2009;Sinclair 1991,2004).However,there have not been many studies that combined the two linguistic approaches,likely because of the surface differences between CGL and CPL.Only a relatively small number of studies have purposefully integrated them(Gries and Divjak 2009;Grondelaers et al.2007;Liu 2010a,2011c,in press).Though not large in number,these studies have managed to show the values of and the potentials for combining CGL and CPL in language research and teaching.It is the purpose of this paper to introduce and promote this integrated approach.The paper first explores the theoretical grounds for combining the two linguistic approaches.Then,drawing on existing studies,including those of the author,the paper describes how the two approaches can be combined to enhance the validity of language research and the effectives of language learning/teaching.The paper ends by discussing the challenges and future directions of employing such a combined approach.

THEORETICAL GROUNDS

To understand the theoretical grounds for combining CGL and CPL in language research and teaching,a basic overview of the two linguistic approaches is first in order.

Cognitive linguistics

Unlike most traditional linguistic approaches—such as structural and generative linguistics,which treat language as an autonomous system by focusing on the formal(e.g.syntactical)aspects of language—CGL considers language an inherent part of the human conceptual system and focuses on meaning(including pragmatics)rather the formal aspects of language.Specifically,CGL views language as a symbolic system composed of symbolic units(which are pairings of form and meaning)signifying human conceptualizations.Hence,CGL posits that linguistic forms or structures(including phonemes,morphemes,and syntax)are generally not arbitrary but motivated by our embodied experience and conceptualizations.For example,due to our embodied experience,we generally conceptualize being up/high/bright/balanced as being positive while being down/low/dark/unbalanced as being negative.These conceptualizations are ubiquitous in language,as evidenced by the following matched English/Chinese expressions:high vs.low spirits/IQ/standard,“on cloud nine”(being extremely happy )vs.“down in the dumps”(being extremely sad/unhappy),bright vs.dark future,balanced vs.unbalanced approach/ecology;高兴vs.低沉,高vs.低智商/水平,光明vs.黑暗的前途,平衡vs.不平衡的方法/生态.

Grammatical structures are also often based on our embodied experience and hence are motivated rather than arbitrary.For instance,based on the human conceptualization that“more is stronger,”repetitions are used for emphasis,e.g.“It is really,really interesting”and“The work is very,very important.”Also,due to the conceptualization that“the closer the two entities,the stronger the bond or transmission between the two if transmission is attempted,”the following two closely-related sentences“I taught him French”and“I taught French to him”do not convey exactly the same meaning.The former sentence implies“him”learned to grasp French,but the latter does not have this implication,thanks to the fact that the learner(N3)in the former sentence structure(N1+V+N3+N2)is closer to the agent/teacher(N1)than in the second sentence structure(N1+V+N2+to N3).As another example,because of our conceptualization of time as spatial—with the past tense/time perceived as being distant away from the present—English speakers use the past tense in the present situation(e.g.“Could you give me some suggestions?”and“Here are two suggestions I thought you might like”)to make their requests/suggestions sound less immediate/demanding(hence more polite).

It is important to note,however,that due to differences in cultural experience,linguistic structures and usages often vary from language to language.For example,as a language of a high-context culture where meaning is often derived from context rather than explicitly expressed,Chinese is not only a non-inflectional language,having no plural and tense inflections,but also a radical pro-drop language,boasting a very high frequency of subject/object deletion as shown in the following exchange:“喜欢不喜欢这本书 [Like the book or not]?”“喜欢 [like].”In contrast,as a language of a low-context culture where things often must be spelt out explicitly,English is an inflectional and non-pro-drop language.Also,in terms of usages,as this author's(Liu 2002,2007)studies show,due to historical and cultural reasons,eating-based idioms(e.g.吃苦/吃亏/吃香/吃败战/吃醋/吃紧/吃透)figure much more prominently in Chinese than in American English,whereas sports-based idioms(e.g.drop the ball/play hardball/strike out/throw a curve ball/touch base with )are far more common in American English than in Chinese.

It is also worth noting that,in CGL,the concept of symbolic units(the basic structure in language)collapses the traditional rigid separation between lexis and grammar.Symbolic units cover a variety of linguistic elements,which range from morphemes(e.g.the past tense ed)to entire clauses(e.g.How do you do?).A symbolic unit or construction can be completely filled(e.g.the grammatical morpheme ed and the phrase tie the knot,)partially-filled(e.g.the“the more...the more...”construction),or unfilled(e.g.the aforementioned ditransitive N+V+N+N “cause to receive”construction).Thus,symbolic units may vary in schematicity,with the unfilled schematic grammatical units being much more schematic than the filled and unfilled constructions.Yet,“all grammatical elements—morphemes,classes,and rules—are...schematic symbolic units”because they are“simply schematizations of particular expressions”(Langacker 1991:46).A schematic construction enables speakers to quickly produce new utterances“in conformity with the specifications of the schema”(Taylor 2002:233).However,constructional schemas do not function the way rules in generative linguistics do:they do not generate sentences.They simply provide models for speakers to follow.

For any linguistic element to become a construction,it has to be highly frequent so that it can be entrenched in a language user's linguistic system.Language knowledge is thus acquired via repeated exposure and use,i.e.it is usage-based,not innate as has been proposed by generative linguistics.The innate theory posits language mainly as a prewired autonomous system in the form of Universal Grammar(UG).This theory of language knowledge is based on an assumed paucity of language input and an assumed ease with which children acquire a language,but both assumptions have been seriously challenged in recent empirical research(Tomsello 2003).According to CGL research findings,language“is acquired‘bottom-up'on the basis of encounters with the language,from which schematic representations are abstracted”(Taylor 2002:592).Furthermore,a large part of our linguistic knowledge is composed of“knowledge of low-level generalizations”and even“knowledge of specific expressions”(Taylor 2002:592),a theory that contrasts sharply with the highly abstract generalizations that form the core of language knowledge in the generative linguistic theory.In short,in usage-based theory,“language is learned from input,using general cognitive mechanisms,sensitive to type and token frequency,resulting in item-specific knowledge and more abstract categories of form-meaning relationships”(Robinson and Ellis 2008:494).

It is also important to note that,because CGL views language as a symbolic system representing human embodied conceptualizations,conceptual operations,such as construal and metaphor,are extremely important in language.Construal refers to how a speaker/writer construes an issue and expresses it.It significantly affects our use of lexical items and grammatical structures,such as the choice of prepositions,tense/aspect,and voice.For example,went over an article and went through an article may refer to the same activity but reflect different construals by the speaker.The utteranceI went over the article accentuates the fact that the speaker read the entire article(likely quickly),whereas I went through the article focuses on the effortful process and detailed attention the speaker paid in reading the article.As an example of the role of construal in the choice of voice,former President Clinton said in response to a reporter's question regarding whether he and his wife made mistakes in their firing of White House Travel Office employees,said,“Mistakes were made”instead of“We made mistakes”.By changing the figure(a CGL term)of the utterance from the Clintons to mistakes—a re-construal—Clinton technically avoided admitting that they made mistakes.CGL's focus on construal,metaphor,and other conceptual operations offers us unique and interesting perspectives in our understanding of language.

Corpus linguistics

On the surface,CPL differs from CGL in that while CGL focuses on the workings of the language in the mind(i.e.something internal),CPL deals mainly with language data(i.e.something external to the mind).Furthermore,whereas CGL is often known as a“non-objectivist”theory of language,CPL is famous for using mainly aquantitative(objectivist)approach to language(Grondelaers etal.2007:150).However,these surface differences are based largely on inaccurate assumptions.The fact that what CGL investigates is often subjective does not mean that the method used to study it must also be subjective(Grondelaers et al.2007).In fact,CGL theories have been built largely on empirical research findings(see for example,Goldberg 1995,2006;Tomasello 2003).Also,although CPL approaches language mainly in a quantitative manner,it inevitably involves hypothesis testing and interpretation of results—operations that are largely subjective in nature(Liu 2010b).Furthermore,as will be shown by the brief discussion of CPL below,CPL shares three commonalities with CGL:it is usage-based;it focuses on meaning;and it also rejects the traditional rigid separation of lexis and grammar as two distinct domains.Most significantly,CGL and CPL complement each other in a very important way:whereas CGL provides valuable theoretical guidance and insights for CPL in data analysis/interpretation,CPL offers CGL“the kind of data that are at the heart of Cognitive Linguistics”(Gries 2008:412).

The usage-based nature of CPL is self-evident thanks to its data-driven approach to language based on authentic language data.CPL uses language frequency measures to identify usage patterns at all structural levels,ranging from individual words and their collocations/colligations to larger structures such as collostructions(a term Stefanowitsch and Gries coined in 2003by applying CGL's concept of constructionin CPL)and sentence patterns shownin pattern grammar,a concept developed by Hunston and Francis(2000).As is the case in CGL where a linguistic item has to have a high frequency to become a symbolic unit/construction,a collostruction in CPL must also have“sufficient frequency of occurrence”(Gries 2008:412).Also,just like CGL,which assumes that language consists mostly of symbolic units that are processed as whole units,CPL holds as one of its most famous findings that language is composed of many pre-/semi-prefabricated expressions whose meanings cannot be completely derived from their individual components.These pre/semi-fabricated expressions/constructions are essential in communication.

The meaning-centeredness of CPL can be best seen in the fact the focus of the approach on language patterns is driven by both an interest in the relationship between form and meaning and a belief that formal distribution differences in language correspond to functional/semantic differences(Gries 2008;Liu 2010b;Liu and Espino 2012;Sinclair 1991).Many corpus studies have successfully demonstrated this relationship by showing how the distributional patterns of a linguistic form reflect its functions/meanings(Divjak and Gries 2006;Liu 2010a;Liu and Espino 2012;Stefanowitsch and Gries 2003).The examination of distribution/usage patterns of linguistic items enabled researchers to identify the unique meanings(especially connonational meanings or“semantic prosodies”)of various linguistic constructions.For example,Stefanowitsch and Gries's(2003)corpus analysis has shown that the N+(be)+waiting to happen construction(as instantiated by accident waiting to happen )and the v+into causative construction(as instantiated by trick/fool someone into doing something )are used primarily in the negative sense.Semantic prosody patterning can also be found in other languages,e.g.in Chinese,whereas the“x造成了y”construction is generally negative,the“x造就了y”construction is typically positive.CPL's focus on pre/semi-fabricated constructions and lexicogrammatical patterns highlights it as an approach that,like CGL,collapses the traditional boundaries between lexis and grammar.

In summary,both CGL and CPL are meaning-focused and usage-based,and they both reject the traditional rigid separation of lexis and grammar.Furthermore,the two approaches offer each other the very theoretical and/or methodological support they each need as viable linguistic approaches.The two approaches are not only compatible but also complementary.Thus,they can and should be combined in language research and teaching,as will be shown in the following two sections.

ENHANCING LINGUISTIC RESEARCH VALIDITY/RELIABILITY BY COMBINING CGL AND CPL

Due to the aforementioned reasons,CGL and CPL,when employed together in linguistic research,can make research findings more valid,reliable,and informative.Several studies have demonstrated this clearly(Ellis and Simpson-Vlach 2009;Gries and Divjak 2009;Gries et al.2005;Gries and Wulff 2005;Grondelaers et al.2007;Liu 2010a,2011c,2011d,in press;Stefanowtsch and Gries 2003).Due to lack of space,we will examine only Grondelaers,Geerarts and Speelman's(2007)and this author's(2011c,in press)studies to illustrate the ways CGL and CPL may be combined in research on language use and the unique values of doing so.

Study on the Dutch word er in the adjunctive-initial presentative sentence

Grondelaers et al.(2007)investigated the use of the Dutch word er(a counterpart of the English there)as an expletive subject in the adjunct-initial presentative sentence structure exemplified by the following two sentences:

1.In 1977was er een fusie tussen Materne en Confilux“In 1997there was a merger between Materne and Conilux.”

2.In the keukenkast was een zoutvat“In the kitchen cupboard was a salt tub.”

As can be seen in the two examples,the use of eris optional in the adjunct-initial type of presentative sentence.For a long time,linguists were unable to clearly identify the rule(s)for the use/nonuse of erin this sentence structure.Using a well-designed corpus including both informal and formal Belgian and Netherlandic Dutch,the researchers successfully identified all the key factors governing the use of er.The first factor is the type of the initial adjunct:while temporal adjuncts(e.g.“In 2010...”)almost always require the presence of er,locative adjuncts(e.g.“On the table...”)typically do not.The second factor is verb specificity:whereas verbs with low specificity(e.g.“be”)demand the use of er,verbs of high specificity(e.g.“stand”)reject it.The third factor is dialectal difference:Netherlandic Dutch uses er significantly less than Belgian Dutch.The final factor is register:informal language tends to use er more often than formal language.

More importantly,by applying the CGL concept of“reference point”(an issue of construal/frame of reference)in their analysis,Grondelaers et al.were able to identify the reasons why eris often used with temporal adjuncts and verbs with low specificity but not with locative adjuncts and verbs with high specificity.A“reference point”is the focus point against which we reference everything else in an utterance.A sentenceinitial adjunct constitutes such a reference point.Locative adjuncts(e.g.“on the table”)are more specific or better reference points than temporal adjuncts(e.g.“in 2010”)because the former type of adjuncts provides better accessibility to(i.e.easier processing/prediction of)the forthcoming information(the real subject)in an utterance by restricting the types of nouns that can serve as the subject.The things that can be placed(or serve as the subject for)“on a table”are clearly much more limited and hence more predictable than those that can occur“in a year,”for almost anything,including non-concrete ones like“riot,”can occur in a year.It is thus much easier to process/predict what may follow“on the table”(a locative adjunct)than what may follow “in 2010”in an adjunct-initial presentative sentence.This difference in the processing effect between locative and temporal adjuncts also exists between verbs of varying degrees of specificity.Verbs with a higher specificity(e.g.sit/stand )offer better accessibility and prediction of their subjects than verbs with a lower specificity(e.g.be/exist),because the things that can serve as the subject of a verb with a high specificity like standare much more restricted and predictable than those that may serve as the subject of a verb with a low specificity like be.

To verify this CGL theory-inspired hypothesis,Grondelaers et al.did an experimental study where they investigated the difference in the amount of time required to read sentences that contained the two different types of adjuncts and verbs of varying specificity.The results indicate that reading sentences involving temporal adjuncts and/or verbs with lower specificity took significantly longer time than reading those with locative adjuncts and/or verbs with higher specificity.This finding confirmed their hypothesis.To further triangulate this finding,the researchers returned to their corpus to check and ascertain again whether er was indeed used mostly in the sentences with temporal adjuncts and/or verbs with low/lower specificity but seldom used in the sentences with locative adjuncts and/or verbs of high/higher specificity.They obtained positive results,confirming their finding once more.Grondelaers et al's study provides a classical example of how CGL and CPL can be combined to make research findings more valid,reliable,and insightful.

Studies of L1and L2use of synonymy

This author's studies(2011c,in press)on synonymy,an important but challenging linguistic phenomenon,offer further evidence about the need and value of combining CGL and CPL.Synonymy is important because it is ubiquitous and necessary for precise and effective communication.Yet,it is difficult because while synonyms express essentially the same meaning,they often convey different perspectives,connotations,and attitudes,i.e.they are not completely interchangeable.It is thus very difficult for linguistics and laymen alike to accurately identify and describe the differences among synonyms.

My(in press)study examined native English speakers'use of two sets of synonymous nouns,authority/power/right and duty/obligation/responsibility,striving to ascertain the semantic and usage differences among the nouns in each set.The study began with a corpus-based behavioral profile(BP)examination of the two sets of nouns used in Mark Davies's(1990-2010)400+ million-word Corpus of Contemporary American English(COCA).Based on the Firth/Halliday/Sinclair lexical semantic theory that the meaning of a lexical item correlates closely with its collocates(Firth 1957;Halliday 1966;Sinclair 1966,1991),the corpus-based BP approach focuses on the collocates or distributional patterns of a lexical item to effectively identify its semantic and usage patterns.Therefore,in my BP analysis,I queried and analyzed the typical pre-nominal adjectives and post-nominal modifying infinitives of the synonymous nouns because these per/post-nominal modifiers can best reveal the meanings of nouns.For example,we say individual right(not individual authority )but regulatory authority/power(not regulatory right).Similarly,we usually say the right to vote but the authority/power to levy(taxes),not vice versa.

The corpus analysis successfully identified the unique semantic/usage patterns of each of the synonymous nouns as well as the minute semantic differences among the synonyms,yielding a clear delineation of the internal semantic structure of each synonym set.Yet,a scrutiny of the examples of the use of the synonyms in the data also shows that while there are clearly well-established semantic/usage patterns,there are some instances of use that break the general patterns.For example,whereas right to vote is the prevalent usage with 749tokens in COCA(i.e.for most native English speakers in most cases,to vote is a right),there are,however,8tokens of the power to vote in COCA.Similarly,while the majority of speakers/writers used power/authority to declare warin the debates regarding whether the U.S.President or Congress has the authority/power/right to declare war,a few used right to declare war(7tokens compared with 42 tokens in COCA).How do we explain such less common or deviated usages?The CGL concept of construal enabled me to find a good explanation not only for such usage variations but also for the general processes involved in synonym use.When speakers choose to use an uncommon or nonconventional usage,they are construing the issue under discussion differently than usual,as can be seen in the following example from COCA:“Our ancestors struggled and died to give us the power to vote.Let's not let them down.Vote!!”This was a quote from a letter to Ebonics(a magazine for Afro-Americans).Clearly,in saying power to vote,this letter writer construed voting more as a power than a right.Similarly,those speakers/writers who opted for the right to declare war expression construed the declaration of war not just as an authority/power issue but also as a moral issue as it concerns the destruction of human lives.

So the CGL theory-inspired corpus analysis suggests that conventional usage(the established frequent usage pattern)and construal constitute two key competing factors in synonym use:speakers/writers typically opt for conventional usage unless they have a unique construal of the situation that calls for a nonconventional usage.However,without asking the speakers/writers about how they made their synonym selection decisions,this hypothesis about synonym use cannot be confirmed.Given that it is impossible to ask the speakers/writers in a corpus for such information(a clear weakness of corpus study),I conducted a forced-choice study where the participants were asked to(1)fill in each missing synonymous noun in sentences(taken directly from COCA but with the target synonyms deleted)by selecting one of the three nouns in each set and(2)describe their rationales for their selection decisions.The results from this elicited data offer convincing support for the finding about the competition of conventional usage and construal in synonym use.Many subjects often mentioned conventional usage as the reason for their synonym selections.Yet,in cases where some of the subjects chose an unconventional usage,they typically described their unique construals as the rationale for their choices.As one example,a subject chose the right to vote in one of the questions dealing with“authority/power/right to vote”because,in her words,“I'm just used to hearing‘right to vote'(equated with suffrage)”but she selected the power to vote in the other authority/power/right to vote question:“...give the voters the to vote for‘None of the Above'”)and her reason was:“Honestly,the other two just seem not to fit well.‘Power'equates ability.”So,one of her choices in this case was driven by conventional usage and the other by a unique construal.

Using basically the same procedures,my 2011cstudy compared the use of four sets of synonyms(two sets of nouns and two sets of adverbs)by both native English speakers and intermediate/advanced Chinese learners of English.The native English corpus used consisted of the spoken and academic written sub-corpora of COCA and the Chinese EFL corpus used was Wen et al.'s(2005)Spoken and Written English Corpus of Chinese Learners(SWECL).The elicited data part of the study used exactly the same procedures as those used my in-press study described above.The Cognitive Linguistics theory-guided analysis of the corpus and elicited data yielded some important findings about L2use/learning of synonyms that could not have been obtained otherwise.The key findings include the following.First,frequency of exposure plays a crucial role in the use/learning of synonyms.Second,L2learners(especially intermediate-level learners)show special difficulty with conventional usages in synonymy and they also substantially underuse and misuse the non-dominant(less-frequent)members in a synonym set.Third,conventional usage and construal are two key competing factors affecting speakers/writers'synonym choice decisions,especially in the case of native English speakers.These findings have useful implications for L2learning/teaching of synonyms,such as the need to provide learners first with adequate input on the conventional collocates of synonyms and then,as learners'L2proficiency increases,to encourage the use of non-dominant members in a synonyms set and pay attention to issues of construal(Liu 2011c).

In short,the above examples show that combining CGL and CPL in research on language use can make our research findings more valid,reliable,and informative.The typical procedure is to begin with a corpus exploration/analysis,then use a CGL theory-based empirical(often experimental)study to test and/or explain the corpus data/findings,and,if necessary,retest the CGL theory/finding with additional corpus analysis(Grondelaers et al.2007;Liu 2011c,in press).Alternatively,one can begin with an experimental study on a CGL-based hypothesis/theory,followed by a corpus analysis to test/confirm the experimental results,or one can directly conduct both an experimental and a corpus study simultaneously for synchronic triangulation of findings(Ellis and Simpson-Vlach 2009;Gries et al.2005;Gires and Wulff 2005).Also,more than one type of experimental procedure can be used in one study to better triangulate the findings,as shown in Ellis and Simpson-Vlach'(2009)study where,to investigate the validity of corpus-generated academic English formulae(constructions),they conducted four experiments including(1)speed of reading and grammaticality judgment,(2)speed of reading and rate of spoken articulation,(3)binding and primed pronunciation,and(4)speed of comprehension and acceptability judgment of formula in context.The challenges involved in doing combined CGL/CPL research will be discussed in the conclusion section.

INCREASING LANGUAGE TEACHING EFFECTIVENESS BY INTEGRATING CGL AND CPL

Rationale

CGL and CPL approaches can also be combined in language teaching to make L2teaching more engaging and effective.There has already been substantial research on how CGL and CPL eac h alone can be used to make L2learning/teaching more effective(e.g.for CGL-inspired language teaching:Boers 2000;Knop et al.2010;Kövecses and Szabó1996;Tyler 2008,2012;for Corpus-based language teaching:Boulton 2009;Cobb 1999;Liu 2011a;Liu and Jiang 2009;Sinclair 2004;Yoon and Hirvela 2004).Yet,there have been few studies on how CGL and CPL can be combined to further enhance L2teaching effectiveness,perhaps due again to the surface differences between the two linguistic approaches.More effort is needed to integrate CGL and CPL in language teaching because,as already noted above,the two approaches are not only compatible but are also complementary,i.e.they need each other to be fully successful.This is especially true when they are used in language teaching.

To understand why,a brief discussion of the value of each approach and its need of the other in language teaching is in order.CGL-inspired language teaching alone can make L2learning more effective by exploring the conceptual motivations of language(Boers 2000;Cho 2010;Kövecses and Szabó1996;Tyler 2012).For example,in an empirical study,Kövecses and Szabó(1996)taught to two groups of EFL students phrasal verbs made up of the particle upand down(e.g.move up,go up,cut down,die down).The students in the experimental group were made aware of the conceptual metaphors that motivate the phrasal verbs,such as“More is up”and“Less is down.”The students in the control group learned the phrasal verbs without exploring the motivating conceptual metaphors.The results indicate that the experimental group significantly outperformed the control group on the achievement test.Other studies have also showed the same positive effect of exploring the motivations of language usages in language teaching,including the teaching of various language structures such as multi-word units,prepositions,and modal verbs(Boers 2000;Cho 2010;Tyler 2012).However,for CGL-inspired exploration of language usages to be valid,authentic and representative language data must be used.Corpora(especially well-designed large ones)are the best and most accessible source of such language data(Juchem-Grundmann and Krennmayr 2010;Liu 2010a).

While CGL-inspired teaching must make use of corpus data,corpus-based/driven language teaching needs to include CGL-inspired language analysis in order to be fully successful.Although corpus-based/driven language learning alone has been shown to help make L2learning more effective thanks to the natural language data and the discovery learning opportunity it offers language learners(Aston 2000;Boulton 2009;Cobb 1999;Liu 2011a;Liu and Jiang 2009),such data-based/driven learning has so far focused mainly on finding language usage patterns/rules,i.e.it seldom explores why the language usage patterns/rules are the way they are.Exploring and understanding the motivations of language usages will not only enable learners to better grasp language(as shown in the research reported above)but also make language learning more engaging because,by focusing on the conceptual motivations of language usages,CGL-inspired teaching makes language learning“a far more natural and enjoyable process”than traditional approaches(Langacker 2008:73).A few studies have already shown how incorporating CGL-inspired analysis in corpus-based/driven language learning may make language learning simultaneously more engaging and successful(Juchem-Grundmann and Krennmayr 2010;Liu 2008c,2010a,2011d).It is important to note,though,that as they are efforts in a new endeavor,these few studies on combining CGL and CPL in language teaching have not provided much direct,hard empirical evidence for the effectiveness of this teaching practice.Yet they have offered substantial indirect evidence with many concrete examples,as will be shown below.

Teaching English for specific purposes:business English

Juchem-Grundmann and Krennmayr(2010)studied how a metaphor-driven approach based on corpus data could enhance L2learners'understanding of business English.As already noted,conceptual metaphor,along with other conceptual operations,plays a key role in language.Much of our language is conceptual metaphor-based(e.g.the expression Google beat Yahoo in the internet search business is based on the conceptual metaphor“business is a game/competition”).Motived by previous research findings that making learners aware of the key conceptual metaphors used in a given discourse can help learner better grasp such language,Juchem-Grundmann and Krennmayr tried to apply the practice in teaching business English.To make sure that the conceptual metaphors taught in business English classes were indeed the ones used in real business English,they first conducted a close analysis of the use of metaphors in a business sub-corpus of the British National Corpus.They identified sports and war as the dominant conceptual metaphors in business English.

Based on their corpus findings,they then did a teaching experiment involving two sections of a business English reading course.One section served as a control group where the students were taught in the traditional way of first studying new business vocabulary in the assigned reading.The other section was taught using the metaphor awareness-first approach where the students were asked first to think about the sports they were familiar with and then to identify the sports metaphors in the reading material.Moreover,the class also explored the relationship between the source and target domains of the conceptual metaphor,i.e.how business was conceptualized as sports and often portrayed in sports terms.The teacher observed very positive effects of the metaphor awareness approach:students taught by this approach were much more active than those in the control group.An oral survey of the students after the course also showed very positive response.The students said they enjoyed the metaphor exploration activities and found them creative and engaging.However,the researchers did not use an objective test to measure and compare the language learning gains between the two sections.So,while the study provided some qualitative data support for corpus-based cognitive analysis,it did not offer any hard supporting evidence based on quantifiable data.

Teaching collocations

My study(2010a)explored how corpus-based cognitive analysis could assist in the learning of collocations,a difficult topic for L2learners.Collocations,such as common English verb+noun(e.g.make a decision/take a break)and adjective+noun(e.g.heavy rain/strong wind)collocations,have long been considered largely arbitrary.Yet,via a corpus-based cognitive analysis of several groups of such collocations,my study has managed to show that collocations are generally not arbitrary but motivated.The first group of the collocations in question are make a trip,take a trip,and have a trip.On the surface,the three“v+a trip”collocations seem to be synonymous and interchangeable.Yet a close examination of the tokens of the collocations in 400+ million-word COCA indicates otherwise.Whereas make a triptypically refers to a business trip,take a trip,the most frequent in the set,mostly means a leisure trip,and have a tripis used primarily as an expression wishing aperson to have a good trip(e.g.have a nice/safe trip).More importantly,a CGL-inspired analysis of the collocations suggests that the different meanings of the three collocations are not arbitrary but are derived from the core meanings of the verbs based on our embodied experience.It is much more purposeful and effortful to make something than to take something;hence making a tripis more purposeful and effortful thantaking a trip.As for have a trip,a common meaning/use of have in English is experience,e.g.had a/an accident/difficult/good day...where had means experienced,which helps explain why have a good/safe trip means experience a good/safe trip.

The same CGL-inspired analysis also applies to most of the other common verb-noun collocations like make/take/have/do something.An examination of the tokens of such collocations in COCA indicate that,in general,the make+Ncollocations(e.g.make a/an change/decision/effort/phone call/plan)express actions that are more purposeful and effortful than the take+Ncollocations(e.g.take a/an break/bus/change/phone call/rest).Have+Ncollocations,as already mentioned,mostly convey the meaning of experiencing something.Do+Ncollocations express primarily routine actions,as shown in do chores/exercises/homework/laundry.

Other collocations examined in the study included heavy rain/strong wind and strong tea/powerful car,two well-known collocation pairs that had often been cited to show the arbitrariness of collocations.Yet these collocations,like most others,are in fact not arbitrary but motivated by our embodied experience.Rain is composed of water and thus has weight,whereas wind has essentially no weight but possesses force.In strong tea,strong,a word often used to describe taste in English,refers to the taste of the tea,not to the force/power of the tea.Powerful in powerful car describes the force of the car(specifically its engine).Furthermore,the corpus query/analysis also shows that while speakers generally use the established strong tea/powerful car collocations,they sometimes also say powerful tea and strong car but they do so to convey different meanings.Powerful teais used to mean herb tea that has powerful medical effects such as tea used for cleansing and weight-loss purposes,a meaning that differs from that of strong tea.Strong carrefers a solidly-built car,as opposed to a car with a powerful engine.In short,the above corpus-based cognitive analyses demonstrate that collocations are generally motivated.Involving L2learners in such corpus-based cognitive analysis should help them understand the motivations of collocations and in turn better grasp these difficult language structures,because studies have repeatedly shown understanding the motivation(s)of a structure/usage significantly enhances its learning(Boers 2000;Boers and Lindsromberg 2008;Kövecses and Szabó1996;Tyler 2012).

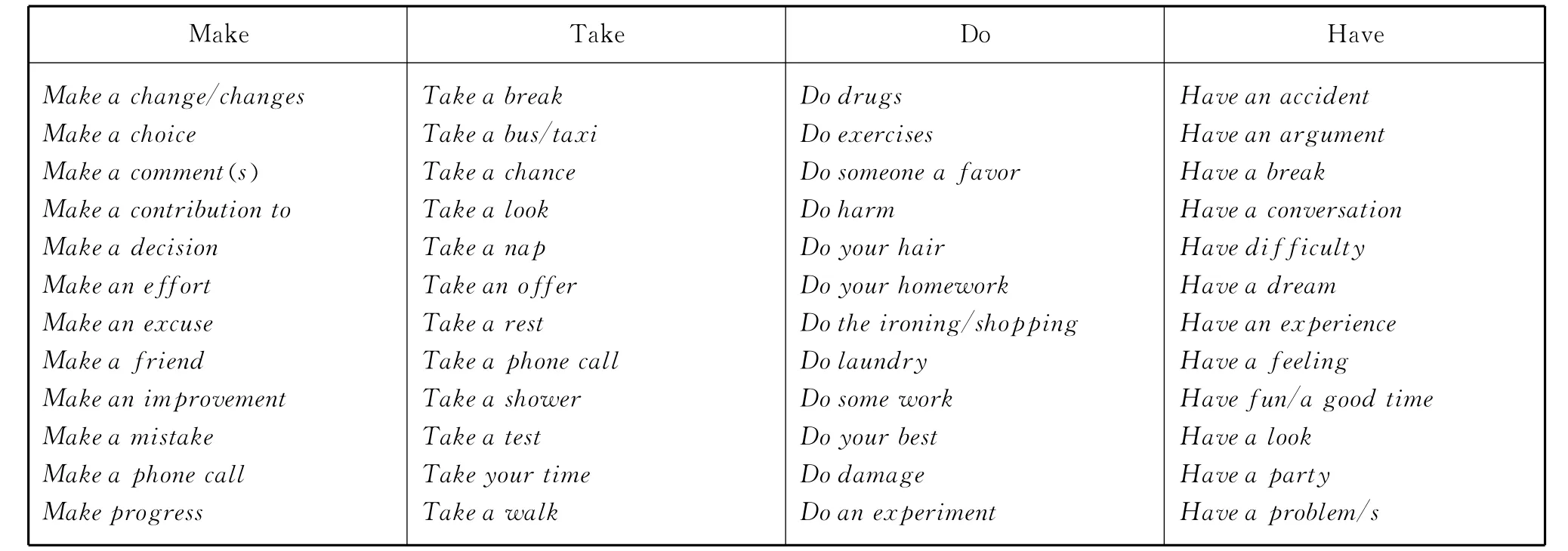

To implement corpus-based cognitive analysis in collocation teaching,we can typically begin by having students query/examine corpus data regarding the patterns of the target collocation.For low level students and/or difficult collocations with uncommon words,teachers can do the corpus query and present students with screened corpus results.For instance,to teach the make/take/do/have-Ncollocations,we can first give students a list of the typical collocations of the verbs based on corpus data(see Table 1adapted from McCarthy and O'Dell 2005,a corpus-based book on collocations).Then we ask students to discuss,based on their embodied experience,questions like:Which verb's/verbs'collocations express actions that involve more initiation,planning,and effort?Which ones express actions that are routine activities?What common semantic pattern/patterns is/are shown in the collocations under each verb?With some guidance from the teacher,students should be able to uncover the semantic patterns of the collocations and their motivations.

Table 1:Typical collocations of everyday verbs

It is important to note,however,that collocations/collostructions that are motivated intralingually may often look arbitrary from a cross-linguistic perspective.For example,due to differences in cultural experience and other historical reasons,a verb may have the same core meaning(s)across most languages but its semantic mapping may vary significantly from one language to another.A look at the use of runand open,two verbs that have the same core meanings in English and Chinese,can illustrate the point.Runis semantically mapped more broadly in English than in Chinese because“run”in English can mean“manage/operate,etc.”(e.g.run an organization/machine/test),meanings that are absent in Chinese.Conversely,openis semantically gridded much more broadly in Chinese,as“open”in Chinese can mean“operate/turn on,etc.”(e.g.开机器/车/灯/电视 ).Therefore,when doing CGL/corpus-based language teaching,teachers should also help students simultaneously learn cultural and linguistic differences between learners'L1and L2.A good understanding of such differences can enhance L2learning(Liu 2010a;Robinson and Ellis 2008)

Teaching other collostructions

Besides collocations,corpus-based cognitive analysis can also be used to more effectively teach other language collostructions(2011b).One example relates to the teaching of the usage patterns of the following two pairs of constructions:come+adjective vs.go+adjective and keep+something+adj vs.leave+something+adj.After having students do a query of the tokens of the collostruction in each pair(a screenshot of the result of such a query from COCA is given in Figure 1),we can ask them whether they notice any patterns regarding the two structures in each pair.With some prodding by the teacher,students should be able to notice that the come/keep-adj tokens in each pair typically express a positive meaning(e.g.came alive/true and kept one happy/healthy )whereas the go/leave-adj tokens usually convey a negative meaning(e.g.went crazy/wrong and left someone homeless/injured ).Then we ask students to think,based on their experience,why this is the case.Such a CGL-inspired analysis should help learners uncover the motivations of the patterns:what we want to come to us and keepare things desirable and what we want to go away from us or leave behind are things undesirable.

Figure 1:COCA concordance results of tokens of come-adjective

Teaching schematic constructions

Corpus-based cognitive analysis can also be used to help learners uncover and learn unfilled,schematic constructions.An example relates to the teaching of what(Goldberg 2005)calls“the implicit/de-profiled theme[object]”construction where the object of a transitive verb is deleted(see examples 3-6below,taken from Goldberg 2005and Liu 2008a).Learning this construction pattern is very important but difficult for ESL learners with a pro-drop L1,such as Chinese.This is because,as already mentioned in section 2.2.,English is not a pro-drop language,i.e.it does not usually allow object deletion while Chinese,on the other hand is a radical pro-drop language.Due to L1influence,Chinese learners of English tend to drop the object in many cases where it is not allowed.In order to help learners understand when limited objectdeletion is allowed in English,we can provide students with representative examples of object-deletion sentences from corpus data such as sentences 3-6and then ask them to think about the motivations for the deletion in each case.

3.Tom blew/sneezed into the paper bag;

4.John gives to charity regularly;

5.Tigers only kill at night;

6.We all have to give and take.

The first reason the students may come up with is likely that the deleted objects were all clearly implied and recoverable(which is the main rationale for object deletion in Chinese).However,being recoverable alone does not warrant object deletion in English.For example,the two omissions of the object“it”in the second sentence of the following actual English utterance often produced by Chinese speakers/writers of English is not acceptable even though it is clear the deleted object“it”refers to X's email address:

7.Do you have X's email address?*Give me if you've(>Give it to me if you've it).

One of two other conditions must be met before an implied object can be deleted(Goldberg 2005;Liu 2008a).First,the object is something unpleasant/inappropriate to mention,as in sentence 3where what Tom blew/sneezed into the paper bag was obviously some bodily fluid—something unpleasant,and in sentence 4where what John gives to charity must be money and it is often considered inappropriate in the West to mention what and how much money one gives to charity.Second,the object is not the focus of the utterance,as in sentences 5and 6where the focus is on the activity(e.g.killing/giving/taking),not the object.2Understanding the motivations for this“de-profiled theme/object”construction should enable students to know better when and where it can be used.

To fully grasp a schematic construction,students should be encouraged to use it in different contexts.Extending a learned construction to new context is how humans acquire language.A good example can be found in the utterance“Don't Rodney King me,”which Jesse Jackson(a renowned Afro-American civil rights leader)made to police when he was being arrested for trespassing at a protest(in front of a prison)against the execution of an inmate.In his utterance,Jackson was asking the police not to treat/beat him like Rodney King,an Afro-American famous for being severely beaten by police in 1992.Jackson's utterance was clearly modeled on the Don't+noun-turned-verb+me construction with Don't baby me as its prototype.

In helping learners effectively grasp a construction,we should first teach them the prototypical form of the construction and then move onto the less prototypical forms.This is because research has shown that skewed input and practice of the prototypical form of a construction facilitates the acquisition of the construction(Ellis 2008).Let us look the example of what is called the wayconstruction(Goldberg 1995;Taylor 2002),as illustrated in the following examples.

8.They found their way to the hotel/conference site;

9.He fought his way out to safety;

10.He worked/slept his way through college/to the top;

11.The country cannot simply spend its way out of this deep recession.

In this construction,find X's way to/out is the most prototypical form whereas spend X's way out of recessionis clearly the least prototypical in the group.We should first give students many examples of the more prototypical forms and have them identify the key components of the construction:(1)the word way functioning basically as an object and(2)an obligatory prepositional adverbial phrase after the word way,such as to/out+NP.After discussing the main semantic/syntactic features of the construction,we can ask students to find more examples of the construction in a corpus and then to produce meaningful sentences of their own based on the examples.It is important to note that creative use of constructions constitutes the foundation of language use in all languages.For example,from the prototypical forms of the Chinese“verb+out(出了)+N”resultative construction“做出了/算出了答案,”Chinese speakers have produced many creative uses of the construction:打出了/闯出了一片新天地and写出了/唱出了新希望/心情/形象.

However,while we encourage our students to use constructions creatively,we should simultaneously help students understand the constraints on each specific construction.This is because it is well-known that L2learners often over-generalize the use of constructions as shown in the following incorrect ESL/EFL utterances modeled on the ditransitive“cause to receive”construction:

12.*I sent Chicago a parcel.

13.*He opened her the door.

A cognitive analysis can help learners understand the constraints of the construction,i.e.understand why these utterances are not acceptable but others like the following two are perfectly fine:

14.I sent Tom a parcel.

15.He opened her a beer.

Although,like 14and 15,utterances 12and 13conform to the syntactic pattern of the ditransitive construction,they differ from them in that they violate the“cause to receive”meaning of the construction.Chicago is a place and hence cannot be a natural receiver of the letter,apoint explained clearly by Goldberg(1995);one has to say I sent a parcel to Chicago.The utterance open someone the door violates the“cause to receive”meaning because,when we open a door for someone,we usually do not and cannot give it to the person.In contrast,open someone a beer works because a person(especially a bar tender/waiter)may indeed open a beer and give it to another person to drink.Knowing constraints like these on the use of a construction can help L2learners avoid overextending the use the construction.

CONCLUSION,CHALLENGES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

This paper has tried to show how combining CGL and CPL may make research on language use more valid/informative and language teaching more engaging/effective.Given that the practice is new,especially in the field of language teaching,there are some questions and challenges that must be considered and addressed.I will discuss the questions and challenges of using the approach in language research first and then those in language teaching.In the discussion,where appropriate,I will briefly mention the types of research that are still needed to test and advance the approach and how they may be done.

Concerning the use of the approach in language research,while there is little question about its value in increasing the validity and reliability of research,there are challenges related to its implementation.First,because corpus analysis is involved,all of the challenges faced by corpus research must also be dealt with in this approach,including ensuring the appropriateness/representativeness of the corpus data and using the right query and analysis corpus analysis methods.For example,in doing a behavioral-profile corpus analysis of lexical semantics and usage patterns,it is very important to know which distributional/collocational features of the lexical item to query/examine,because the distributional/collocational patterns that are informative for the study of lexical items often vary from one part of speech to another(Liu 2010b,in press;Liu and Espino 2012).It is also important,but often difficult,to correctly analyze/interpret corpus research results because sound interpretation of corpus research results requires not only strong linguistic knowledge but also patience and effort.It is often a slow and tedious process to tease out the fine-grained semantic nuances of a lexical item.Second,CGL theories are complex and abstract in nature.To apply and/or test them appropriately in a given study calls for a solid grasp of CGL concepts and empirical(especially experimental)research methodology as well as a thoughtful consideration of what specific CGL theory and research design work best for the research questions at hand.Third,the triangulation of CPL and CGL-based research findings demands an enormous amount of time,effort,and knowledge/skills.

Compared with its use in language research,the practice of combining CGL/CPL in language teaching faces even more serious questions and challenges.First and foremost,as mentioned earlier,although there has been ample empirical research showing how CGL and CPL can each be used alone to make language teaching more effective,there has not yet been any empirical study that directly and objectively tested the effectiveness of the combined teaching practice.The few existing studies that did explore this teaching practice have offered only indirect support about its effectiveness.This lack of direct empirical research on this teaching approach may,however,be a blessing in disguise for language teachers and researchers alike because it presents us with an excellent opportunity to conduct empirical studies on this issue.An ideal empirical study in this regard will likely involve a comparison of the effectiveness of this new approach against that of a traditional teaching approach or an approach that uses either CGL or CPL alone.The comparison should be based on an objective measurement of the students'learning gains produced by each teaching approach.

The second main issue involved in combining CGL and CPL in language teaching is that there are many variables that may affect the effectiveness and/or feasibility of the approach,such as learner age,learning style,and learning environment(including the accessibility of corpora).Age is a factor because corpusbased cognitive analysis requires mature cognition and a decent amount of world experience;therefore this approach will not work well for young learners due to their limited cognitive ability and experience.Also,while analytical learners may thrive with the approach,holistic learners may suffer.It seems,though,that this teaching approach may work well for many Chinese college students,thanks to their cognitive maturity and the reported wide use of analytical learning/teaching strategies in the Chinese classroom.Yet Chinese college English teachers should still be cautious when using the approach because of the likely variations in students'learning styles.Regarding learning environment factors,access to corpora for both teachers and students is necessary for the approach to be fully functional.The approach may still work if only the teacher has access to corpora,however,though less effectively.The teacher can print out and give students corpus search results for them to study.Of course,besides the two aforementioned major issues,all of the questions and challenges related to the use of the approach in language research mentioned earlier are also relevant to the use of the approach in language teaching.

However,despite the questions and challenges,combining CGL and CPL in language research and teaching is a promising and worthy effort in our quest for more valid and informative research findings and more engaging and effective language teaching.Hopefully,this article will inspire more language teachers and researchers to join this worthy endeavor.

NOTES

1 The terms“theories”and“approaches”are combined with a slash because there has been a disagreement regarding whether corpus linguistics is a theory or merely an approach.Also,capital initials are used for Cognitive Linguistics here to refer to the cognitive linguistic theory developed by,among others,Langacker(1987,1991)and to differentiate it from other cognitive linguistic theories,such as generative linguistics.

2 There are also a few situational contexts that license English object deletion,such as instructions on food/medicine containers,e.g.“Mix/shake well before use”(Liu 2008a).For lack of space,they are not discussed,however.

Aston,G.(ed.).2001.Learning with Corpora.Houston,TX:Athelstan.

Biber,D.,S.Conrad,and R.Reppen.1998.Corpus Linguistics:Investigating Language Structure and Use.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

Boers,F.2000.‘Metaphor awareness and vocabulary retention,'Applied Linguistics 21:553-71.

Boers F.and S.Lindstromberg.2008.‘How cognitive linguistics can foster effective vocabulary teaching'in F.Boers and S.Lindstromberg(eds):Cognitive Linguistic Approaches to Teaching Vocabulary and Phraseology.Berlin:Mouton de Gruyter,pp.1-61

Boulton,A.2009.‘Testing the limits of data-driven learning:language proficiency and training,'ReCALL21:37-54.

Cho,K.2010.‘Fostering the acquisition of English prepositions by Japanese learners with networks and prototypes'in S.D.Knop,F.Boers and A.D.Rycker(eds):Fostering Language Teaching Efficiency Through Cognitive Linguistics.Berlin:Mouton de Gruyter,pp.259-75.

Cobb,T.1999.‘Breadth and depth of lexical acquisition with hands-on concordancing,'Computer Assisted Language Learning12:345-60.

Divjak,D.and S.Th.Gries.2006.‘Ways of trying in Russian:clustering behavioral profiles,'Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory2:23-60.

Ellis,N.2008.‘Usage-based and form-focused language acquisition:the Associative learning of constructions,learned attention,and the limited L2endstate'in P.Robinson and N.Ellis(eds):Handbook of cognitive linguistics and second language acquisition.London:Routledge,pp.372-405.

Ellis,N.and R.Simpson-Vlach.2009.‘Formulaic language in native speakers:Triangulating psycholinguistics,corpus linguistics,and education,'Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory5:61-78.

Firth,J.R.1957.Papers in Linguistics,1931-1951.Oxford:Oxford University Press.

Goldberg,A.E.1995.Constructions:A Construction Grammar Approach to Argument Structure.Chicago:University of Chicago Press.

Goldberg,A.E.2005.‘Argument realization:the role of constructions,lexical semantics and discourse factors'in J.Ostman and M.Fried(eds):Construction Grammars:Cognitive Grounding and Theoretical Extensions.Amsterdam:Benjamins.

Goldberg,A.E.2006.Constructions at Work:The Nature of Generalization in Language.Oxford:Oxford University Press.

Gries,S.Th.2008.‘Corpus-based methods in analyses of second language acquisition data'in P.Robinson and N.Ellis(eds):Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics and Second Language Acquisition.London:Routledge,pp.406-32.

Gries,S.Th.and D.Divjak.2009.‘Behavioral profiles:a corpus-based approach towards cognitive semantic analysis'in V.Evans and S.Pourcel(eds):New Directions in Cognitive Linguistics.Amsterdam:Benjamins,pp.57-75.

Gries,S.Th.,B.Hampe,and D.Schönefeld.2005.‘Converging evidence:Bringing together experimental and corpus data on the association of verbs and constructions,'Cognitive Linguistics 16:635-76.

Gries,S.Th.and S.Wulff.2005.‘Do foreign language learners also have constructions?Evidence from priming,sorting,and corpora,'Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics 3:182-200.

Grondelaers,S.,D.Geeraerts,and D.Speelman.2007.‘A case for a cognitive corpus linguistics'in M.Gonzales-Marquez,I.Mittelberg,S.Coulson and M.Spivey(eds):Methods in Cognitive Linguistics.Amsterdam:Benjamins,pp.149-69.

Halliday,M.1966.‘Lexis as a linguistic level'in C.Bazell,J.Catford,M.Halliday and R.Robins(eds):In memory of J.R.Firth.Harlow:Longman,pp.148-62.

Holme,R.2009.Cognitive Linguistics and Language Teaching.New York:Palgrave.

Hunston,S.and G.Francis.1998.‘Verbs observed:a corpus-driven pedagogical grammar,'Applied Linguistics 19:45-72.

Hunston,S.and G.Francis.2000.Pattern Grammar:A Corpus-driven Approach to the Lexical Grammar of English.Amsterdam:Benjamins.

Juchem-Grundmann,C.and T.Krennmayr.2010.‘Corpusinformed integration of metaphor in materials for the busi-ness English classroom'in S.D.Knop,F.Boers and A.D.Rycker(eds):Fostering Language Teaching Efficiency Through Cognitive Linguistics.Berlin:Mouton de Gruyter,pp.317-35.

Knop,S.D.,F.Boers,and A.D.Rycker(eds).2010.Fostering Language Teaching Efficiency through Cognitive Linguistics.Berlin:Mouton de Gruyter.

Kövecses,Z.and P.Szabó.1996.‘Idioms:a view from cognitive linguistics,'Applied Linguistics 17:326-55.

Langacker,R.W.1987.Foundations of Cognitive Grammar:Theoretical Prerequisites.Stanford:Stanford University Press.

Langacker,R.W.1991.Foundations of Cognitive Grammar:Descriptive Application.Stanford:Stanford University Press.

Langacker,R.W.2008.‘Cognitive grammar as a basis for language instruction'in R.P.Roberson and N.Ellis(eds):Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics and Second Language Acquisition.London:Routledge,pp.66-88.

Liu,D.2002.Metaphor,Culture,and Worldview:The Case of American English and the Chinese Language.Lanham,MD:University Press of America.

Liu,D.2007.Idioms:Description,Comprehension,Acquisition,and Pedagogy.London:Routledge.

Liu,D.2008a.‘Intransitive or object deleting:Classifying English verbs used without an Object,'Journal of English Linguistics 36:289-313.

Liu,D.2008b.‘Linking adverbials:An across-register corpus study and its implications.'International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 13:491-518.

Liu,D.2008c.‘Adequate language description in L2research/teaching:The case of pro-drop language speakers learning English,'International Journal of Applied Linguistics 18:274-93.

Liu,D.2010a.‘Going beyond patterns:Involving cognitive analysis in the learning of collocations,'TESOL Quarterly 44:4-30.

Liu,D.2010b.‘Is it a chief,main,major,primary,or principal concern:A corpus-based behavioral profile study of the near-synonyms,'International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 15:56-87.

Liu,D.2011a.‘Making grammar instruction more empowering:A case study of corpus use in the learning/teaching of grammar,'Research in the Teaching of English 45:353-77.

Liu,D.2011b.‘The most frequently-used phrasal verbs in American and British English:A multi-corpus examination,'TESOL Quarterly45:661-88.

Liu,D.2011c.‘L1and L2use of synonymy:A corpus and elicited Data Analysis and its implications'.Paper presented at AAAL Annual Conference,Chicago,IL,March 26-29,(now under review at The Modern Language Journal).

Liu,D.2011d.‘Applying contemporary linguistic theories in language teaching'in Y.Leung(ed.):Selected Papers from 2011PAC/the 20th International Symposium on English Teaching.Taiwan,Taipei:Crane,pp.71-82.

Liu,D.2012.‘The most frequently-used multi-word constructions in academic written English:A multi-corpus study,'English for Specific Purposes 31:25-35.

Liu,D.in press.‘Salience and construal in the use of Synonymy:A study of two sets of near-synonymous nouns.'Cognitive Linguistics.

Liu,D.and M.Espino.2012.‘Actually,genuinely,really,and truly:A corpus-based behavioral profile study of the near-synonymous adverbs,'International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 17:198-228.

Liu,D.and P.Jiang.2009.‘Using a corpus-based lexicogrammatical approach to Grammar instruction in EFL and ESL contexts,'Modern Language Journal 93:61-78.

McCarthy,M.and F.O'Dell.2005.English Collocations in Use:Intermediate. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

Pütz,M.,S.Niemeier,and R.Dirven.2001.Applied Cognitive Linguistics I:Language Pedagogy.Berlin:Mouton de Gruyter.

Robinson,P.and N.Ellis.2008.‘Conclusion:cognitive linguistics,second language acquisition,and L2instructionissues for research'in P.Robinson and N.Ellis(eds):Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics and Second Language Acquisition.London:Routledge,pp.489-545.

Sinclair,J.1966.‘Beginning the study of lexis'in C.Bazell,J.Catford,M.Halliday and R.Robins(eds):In Memory of J.R.Firth.Harlow:Longman,pp.412-29.

Sinclair,J.1991.Corpus,Concordance,and Collocation.Oxford:Oxford University Press.

Sinclair,J.(ed.).2004.How to Use Corpora in Language Teaching.Amsterdam:Benjamins.

Stefanowitsch,A.and S.Gries.2003.‘Collostructions:Investigating the interaction between words and constructions,'International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 8:209-43.

Taylor,J.R.2002.Cognitive Grammar.Oxford:Oxford University Press.

Tomasello,M.2003.Constructing a Language:A Usagebased Theory of Language.Cambridge,MA:Harvard U-niversity Press.

Tyler,A.2008.‘Cognitive linguistics and second language instruction'in P.Robinson and R.Ellis(eds):Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics and Second Language Acquisition.London:Routledge.

Tyler,A.2012.Cognitive Linguistics and Second Language Learning:Theoretical Basics and Experimental Evidence.London:Routledge.

Wen,C.,L.Wang,and M.Liang.2005.Spoken and Written English Corpus of Chinese Learners.Beijing:Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

Yoon,H.and A.Hirvela.2004.‘ESL student attitudes toward corpus use in L2,'Journal of Second Language Writing13:257-83.