Winnie the Pooh and the Ice Festival Too

By Thomas Rippe

Winnie the Pooh and the Ice Festival Too

By Thomas Rippe

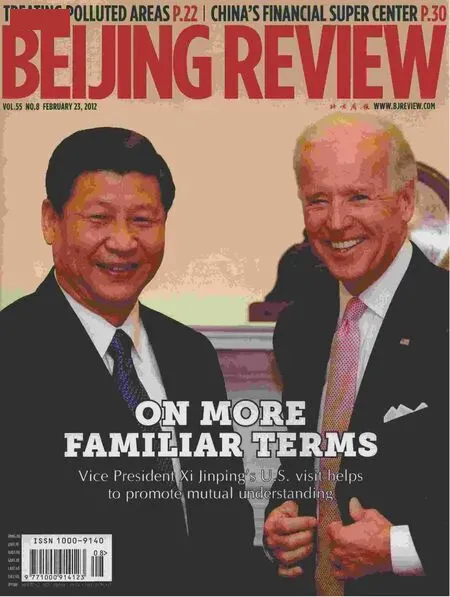

POSING FOR A PHOTO: W innie the Pooh and friends m ade entirely o f snow. Disney is one o f m any large corporations on disp lay at the Harbin Snow and Ice Festival

I first went to the Harbin Snow and Ice Festival in 1996. I remember the train ride—it took 22 hours from Tianjin.And I remember the cold—locals laughed at me for only wearing four pairs of trousers. I recently returned to Harbin and found that,like everything else in China, the festival is not what it was.

Ice has come to define Harbin. Without its famous ice festival the city would be just another dusty, rusty town in China’s frigid northeast. In winter, daytime temperatures hover around -15 Celsius, and at night it can drop to -30 or lower.But instead of being embarrassed at the obvious insanity of living in such a place, Harbin flaunts its frozen wonders. The ice sculptures used to be confined to a single urban park. But they’ve since spread like a fungus across the city. A massive display of illuminated ice pillars greets arrivals at the busy train station. The train from Beijing now takes only eight hours, and tourists flock from around the country. Ice sculptures line many of the main streets and fi ll the centers of roundabouts. Tourists on Zhongyang Avenue, the city’s popular shopping and nightlife spot, pose for photos on benches made of ice and in front of a giant thermometer that tells you exactly how mind-numbingly cold it really is. Photographers have to work quickly so they can get their shots before their cameras freeze.

But all this is just an appetizer, or more like a giant sign post pointing you toward the main event. Everything and everyone is directed towards the ice festival. Every hotel offers a ticket and transport package. If you want to go on your own, no problem. Every cab driver in the city will happily take you there, for free, after you visit the cabbie’s favorite ticket agent to pick up your “discount” tickets.

Tickets are 300 yuan ($47.6), a lot of money to go stand around in the freezing cold, and downright outrageous compared to the 90 yuan($14.3) you pay for a warm bus ride around the nearby Siberian Tiger Park. And yet the crowds at the ice festival are far bigger.

Reasonable people who wish to avoid frostbite head out to the festival during the day, when temperatures are less ridiculous. But the busiest time at the festival is just after dark, when the lights come on. The highlight of the festival is the collection of large structures built entirely out of ice, and lit from within by multicolored lights encased in the ice. There are Chinese pagodas and European castles, many w ith ice slides popular w ith kids and a few adults. This year has a Russian theme, and the central structure sits crowned with onion-shaped domes reminiscent of St. Basil’s Cathedral in Moscow’s Red Square.

The most striking difference from the festival I went to over 15 years ago is how commercial it has become. Just under the highest dome of the main structure sits a giant illuminated sign promoting the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China. The walkway from the main gate to the center structure is lined w ith giant snow sculptures depictingPirates of the Caribbean,Winnie the Poohand other Disney classics. Just to the side of the walkway a huge bottle-shaped ice sculpture promotes Harbin Beer, and another a bit farther along promotes Coca-Cola. At one end of the park a gigantic KFC provides visitors much-needed food and warm th. I felt like I’d paid 300 yuan for the privilege of having a bunch of advertising thrown at me.

It wasn’t like this in 1996. The festival was centrally located in Zhaolin Park, and most people could walk there. Now you have to take an expensive cab ride across the Songhua River to the edge of the city. Back then tickets were an affordable 15 yuan ($2.38), and after the peak evening crowds had passed it was free. The confined space of the park allowed for only a few large structures, but the forested walkways were lined w ith beautiful smaller sculptures. And there wasn’t a corporate sponsor in sight. A few people came in from out of town, but the ice festival was mostly a fun way for locals to pass the interminable winters.

These days the trains are faster, and the hotels are nicer and more numerous. The ice festival creates needed jobs and income in a city that struggles to keep up w ith richer places farther south. And I suppose that’s progress. I won’t be going to the Ice Festival again. But if I could I’d happily go back to that festival in 1996.