WISDOM OF THE OLD GENERATION

WISDOM OF THE OLD GENERATION

Forty years ago this month, U.S. President Richard Nixon’s visit to China ended more than two decades of estrangement between the two countries. At the conclusion of this icebreaking trip, the Sino-U.S. Joint Communiqué was issued in Shanghai on February 28, 1972. The Shanghai Communiqué, which opened the door to the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and the United States, remains one of the cornerstones of Sino-U.S. ties.

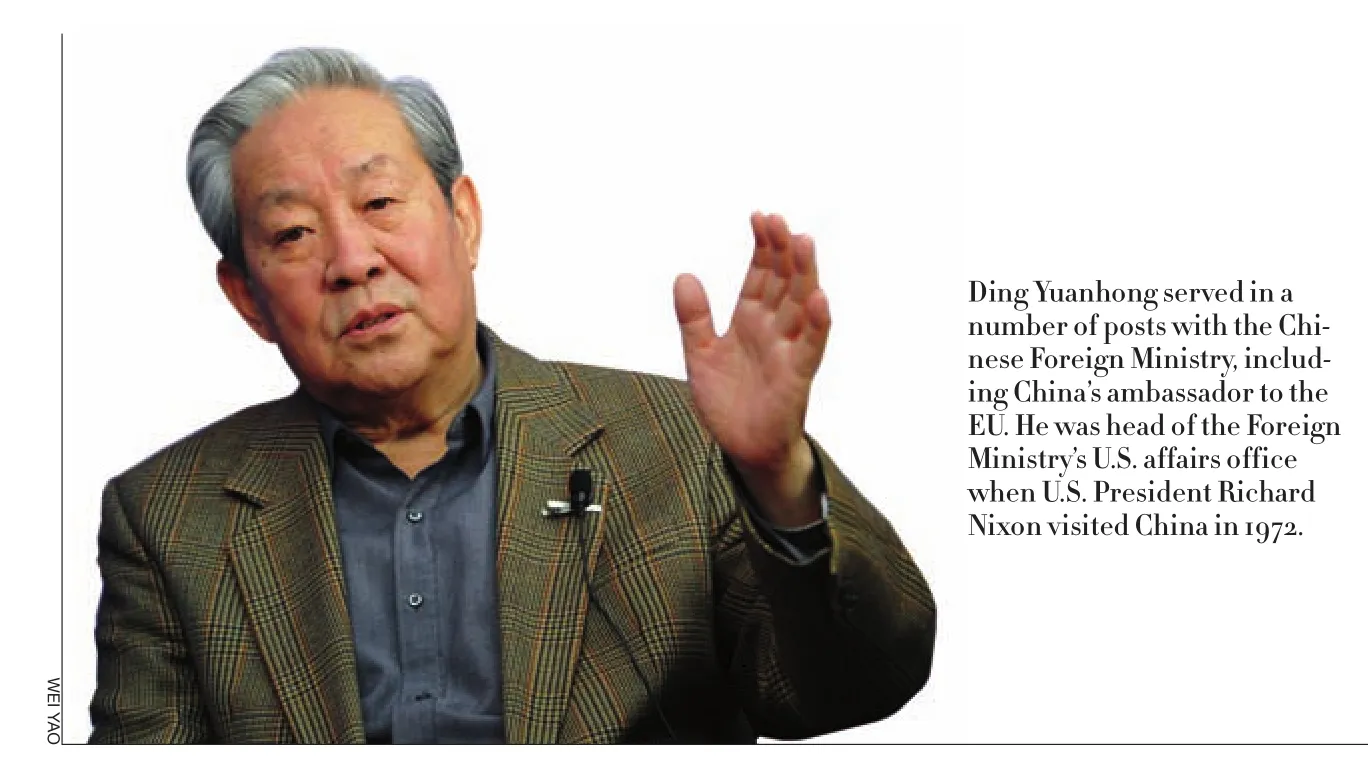

In a recent interview with Beijing Review reporters Ding Zhitao and Yu Lintao, former Chinese diplomats Ding Yuanhong and Zhao Jihua recalled the negotiation process of the Shanghai Communiqué and elaborated on the document’s enduring significance. Excerpts follow:

Beijing Review: You witnessed the historic visit of Nixon and the hard negotiation process of the Shanghai Communiqué. Could you recall the international background before the release of the communiqué?

Ding: The Shanghai Communiqué was issued during Nixon’s visit to China. It was an important achievement after bilateral relations were frozen for more than 20 years. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, the United States went on to support the Kuomintang authorities in Taiwan and regarded the PRC as a foe. It also placed an embargo on trade and denied the PRC’s sovereignty over Taiwan, which caused longtime separation between China’s mainland and Taiwan.

In the late 1960s, the international situation underwent great changes. On the one hand, competition for world hegemony became more and more intense between the Soviet Union and the United States. In the meantime, the Viet Nam War caused headaches for Washington policymakers. On the other hand, Sino-Soviet relations took a turn for the worse, from ideological divergence to border clashes. Against this backdrop, both Beijing and Washington had the will to improve bilateral ties.

What were the main barricades and disputes during the negotiations of the Shanghai Communiqué? And how was the ice broken?

Zhao: Henry Kissinger visited China in July 1971 as Nixon’s special envoy and announced the U.S. president would visit China the next year. The U.S. side insisted that the visit should come with certain achievements. Otherwise, the allies of the United States as well as Nixon’s political rivals would criticize the visit as Nixon’s pilgrimage to the Middle Kingdom. At that time, without diplomatic relations between the two countries, Nixon’s trip to Beijing as U.S. president was itself a kind of political success of China. But China didn’t get a draft of what kind of achievements the two countries might get during Nixon’s visit. During Kissinger’s second visit to Beijing in October 1971, the U.S. side was fully prepared. Kissinger brought a draft for a joint communiqué. However, China could not agree on the articles of the draft and claimed that it could not be used as the basis for negotiations.

Ding: The U.S. draft was just a pile of rhetoric that described the agreements of the two sides. It aimed to show Nixon’s visit to China was successful. The draft didn’t mention the divergence of the two sides at all. Premier Zhou Enlai thought the draft was not acceptable. Zhou said China and the United States had been isolated from each other for more than 20 years and they held many conflicting positions. If they covered up their differences, the two countries would sow seeds of future trouble, he said.

Zhao: Therefore, we drafted a new solution, which proposed an unconventional format for the communiqué. It was impossible that the two could totally agree with each other. The solution therefore required the two sides to basically agree to disagree, each stating its views in separate paragraphs. At the beginning, Kissinger was astonished at the proposal and thought it unacceptable. To break the deadlock, Premier Zhou explained to Kissinger patiently that it was good for both sides to adopt this format. Listing our differences shows both China and the United States hadn’t changed on certain positions. It was helpful for Washington to soothe the feelings of its allies and political rivals. It also showed the world that China would not abandon its principles to improve relations with the United States. What’s more, the common points sought from huge differences are more valuable and reliable. Kissinger agreed at last.

During the negotiations, much time had been spent on wording. At that time, phrases such as “anti-imperialism,” “countries want independence,” “nations want liberation” and“the people want revolution” were commonly used as slogans in China. Kissinger said if the phrases were used in the communiqué, it would be like the U.S. president coming to China for legal judgment. He especially disliked the word “revolution” in the phrase“people want revolution” and suggested using“justice” instead. Later, the two sides agreed to use “progress” after hot debating.

Considering the domestic situation at the time, a little change of the widely used slogan might cause a sensation in China. The Chinese side later proposed to reuse the phrase “the people want revolution.” In order to persuade Kissinger, Vice Foreign Minister Qiao Guanhua even quoted U.S. history. Qiao said American people should not be afraid of revolution, because they call the American War of Independence a revolution. Then the U.S. side accepted the saying.

Another controversial word was “acknowledge.” In the English version of the communiqué an article says: “The United States acknowledges that all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China and that Taiwan is a part of China. The United States Government does not challenge that position.” At first, we thought the word “acknowledge” was not suitable here and insisted replacing it with “recognize.” But the U.S. side stood fast. After consulting the dictionary dozens of times, we accepted the word.

The official negotiation process of the Shanghai Communiqué was pretty hard during Nixon’s visit. The two sides, headed respectively by Qiao and Kissinger, had in all 11 rounds of talks during seven days.

At that time, the common goal of the two sides was to open the door to the normalization of bilateral relations. No topics about establishing diplomatic relations were referred to in the negotiations. However, to improve bilateral relations, the two sides needed to make progress on the Taiwan question. The Chinese Government insisted that the United States should withdraw its forces from Taiwan because its military presence on the island was a breach of China’s sovereignty. But the U.S. side claimed that the withdrawal of U.S. forces must be linked with the peaceful settlement of the Taiwan question. China regarded the precondition as interference in our internal affairs. After fierce debates, the two sides agreed on the following statement,“It (the United States) reaffirms its interest in a peaceful settlement of the Taiwan question by the Chinese themselves. With this prospect in mind, it affirms the ultimate objective of the withdrawal of all U.S. forces and military installations from Taiwan.”

What’s the significance of the Shanghai Communiqué for the later Sino-U.S. relations and the development of the whole international pattern?

Ding: After the issuance of the Shanghai Communiqué, the Sino-U.S. relationship entered a new stage. Though bilateral ties went through ups and downs, the United States has not given up the principles included in the communiqué, especially the one-China principle. If the United States had given up the principle, the basis of the Sino-U.S. relationship would have been gone. From the global perspective, Nixon’s visit changed the triangle relations between China, the United States and the Soviet Union, which is of great significance to international relations. After that, many Western countries began to improve relations and established diplomatic relationships with China.

What experience has China’s diplomacy accumulated from the negotiations of the Shanghai Communiqué?

Ding: Nixon’s visit to China and the issue of the Shanghai Communiqué set a good example for Chinese diplomacy. We try to seek consensus, but we should never give up our fundamental principles. Seeking common ground while reserving differences is an effective way to deal with international affairs.

The principle of non-interference in internal affairs of other nations is also a fundamental part of Chinese diplomacy as well as the UN Charter. We do not interfere in the internal affairs of other countries, nor do we allow other countries to interfere in our internal affairs. We should never abandon the principle. If we gave it up, we might make temporary progress on some issues, for example on the Syrian issue. But the solutions would be likely to backfire in the future.

The reason why we made great efforts to demonstrate our stance on many international issues is that there are essential differences the diplomatic policies of China and Western countries. While the United States pursues world leadership, China calls for the equality of nations, big or small, and non-interference in internal affairs. I believe our policy will be welcomed by other nations in the long run.

Recently, the United States has been shifting its strategic focus to the Asia-Pacific region. Some claim it is out of economic concern for the huge Asia-Pacific market, while others believe it is a kind of containment of China. What’s your opinion? Ding: The rise of China is one of the factors of the United States’ return to the Asia-Pacific region. What’s more, the focus of the entire international pattern is shifting from the West

February 21, 1972 to the East. In the following decades, besides the United States, many of the great powers will be in the region, including China, Japan, and India. The economic power of Asia now has surpassed that of Europe. The development trend of the world inclines to newly emerging countries. At present, the trade volume of Japan, South Korea and ASEAN with China are much larger than their trade with the United States. To keep its superpower position, Washington certainly will shift its strategic focus to the East and hope to benefit from the development of the region.

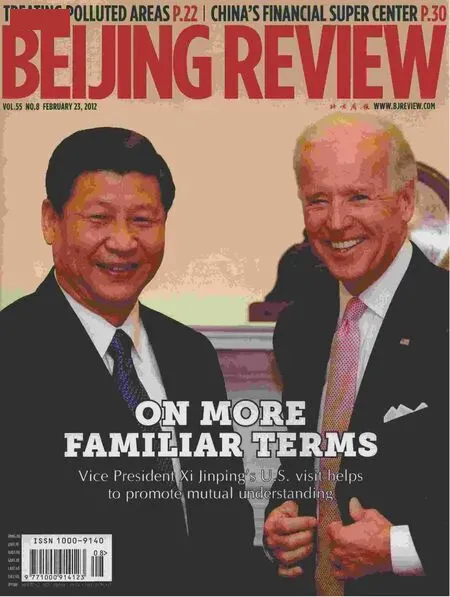

Vice President Xi Jinping recently visited the United States. How do you think the visit will affect the future Sino-U.S. relations?

Ding: During his visit, Vice President Xi emphasized the importance of maintaining the smooth development of Sino-U.S. relations. However, a good bilateral relationship needs efforts from both sides. For example, the U.S. side always mentions its trade deficit with China, but it strictly restricts its hi-tech exports. We want to buy, but the Americans won’t sell to us. How can the trade be balanced? As Premier Wen Jiabao said, we have bought many Boeing airplanes, and most of the soybeans Chinese people consume are imported from the United States. We cannot take Boeing airplanes and eat soybeans every day. Besides these, we want to buy other products from the United States.

Zhao: In the last century, differences between China and the United States were almost all rooted in ideological divergence. Now, clashes between the two countries are more specific, including the U.S. trade deficit and the exchange rate of the yuan. With the rise of China’s international status and its expansion to the world market, conflicts between the two are increasing and becoming more and more complicated. Thus, higher wisdom is needed for the leaders of the two countries for better relations.