乔治·惠特曼:作家文人的资助者

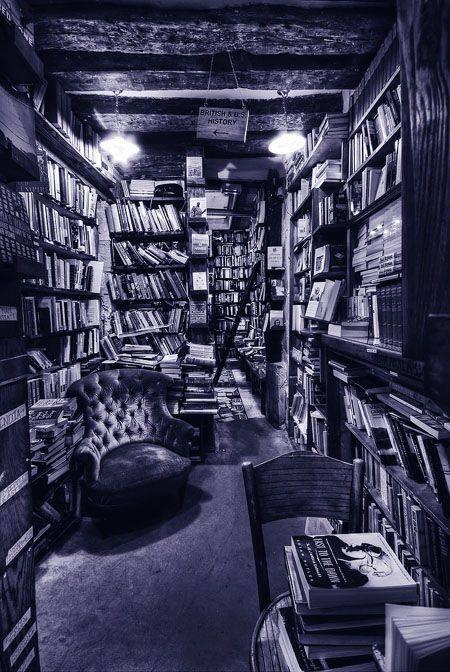

Shakespeare and Company was only part bookshop; it was also part library, part youth hostel and part cultural shrine. As Anas Nin1 recorded in her Paris diaries of the 1950s: “And there by the Seine was the bookshop... an Utrillo2 house, not too steady on its foundations, small windows, wrinkled shutters. And there was George Whitman, undernourished, bearded, a saint among his books, lending them, housing penniless friends upstairs, not eager to sell, in the back of the store, in a small overcrowded room, with a desk, a small stove. All those who come for books remain to talk, while George tries to write letters, to open his mail, order books. A tiny, unbelievable staircase, circular, leads to his bedroom, or the communal bedroom, where he expected Henry Miller3 and other visitors to stay.”

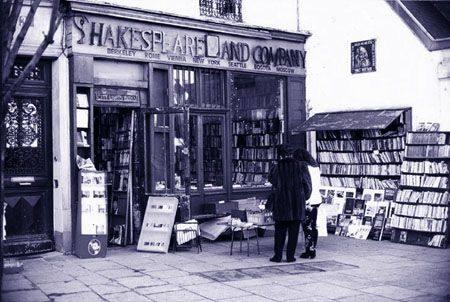

The original Shakespeare and Company had been founded by Sylvia Beach, an American expatriate, early in the last century when Paris became the spiritual home of a group of expatriate writers including Ernest Hemingway, Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, who had been drawn to the city by its permissive ways and its cheap hotels, restaurants and bars.4

The shop became a place for English-speaking writers and intellectuals to meet their French counterparts. It became internationally famous in 1922 when Sylvia Beach published James Joyces Ulysses, after it had been condemned as obscene in Britain and America.5 But, following the Nazi occupation, Sylvia Beach closed the store.

1951 was the year that this legacy was carried on—George Whitman bought a bankrupt grocery at 37 rue de la Bcherie, on the Left Bank6 opposite Notre-Dame, and turned it into a library and bookstore. It was originally called “The Mistral” but in 1964, after Sylvia Beachs death, Whitman renamed the shop as a sign of respect.

Whitmans “rag-and-bone shop of the heart” attracted a new generation of expatriate writers and literati, including Samuel Beckett, Henry Miller and Lawrence Durrell, Berthold Brecht and Arthur Miller, and the “beat generation” writers William Burroughs, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg.7 Burroughs consulted Whitmans medical and psychiatric books while working on Naked Lunch. “He was addicted to drugs,” Whitman recalled,“and not very communicative.” Ginsberg blotted his copybook8 by stealing back the illustrated notebooks he had sold to Whitman for $100 apiece.

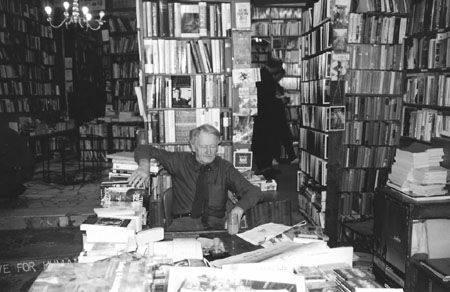

An odd blend of dishevelled eccentricity and prodigal generosity, Whitman presided over his “little socialist republic pretending to be a bookshop” with a heroic disdain for modern conveniences such as telephones, security cameras or credit cards (which were welcome, but only as a means to prise open doors).9 There was no catalogue: Greek encyclopedias jostled with books about war and modern novels, filling the shelves or lying stacked in heaps.10

Whitman displayed a blithe disregard for money, often informing customers that the book they were perusing was not for sale and remaining philosophical when the cash box disappeared — a regular occurrence.11 Yet while more commercially minded bookshops were being taken over or going to the wall, Whitman weathered the depredations of beat poets and hippies, and survived the 1968 student riots and numerous tax audits by the French authorities.12 Quite how he did it remained something of a mystery.

George Whitman was born at Salem, Massachusetts, on December 12, 1913, the son of Walt Whitman—not the poet, but an itinerant13 physics professor. George often claimed to be “the illegitimate great-grandson of Walt Whitman”but, like many stories which he told about himself, this was almost certainly untrue.

His childhood was spent on the move as his fathers job took him to China, Greece, Turkey and Western Europe. After studying for a degree in Journalism at Boston University, he set off on a seven-year odyssey through the United States, Mexico and Central America, hitchhiking, riding freight cars and begging, working where he could.14 He intended to travel the world, but came to a dead end in Panama at a“jungle of quicksand, mud, and mangrove swamp”.

The kindness of strangers and the poverty he encountered on his journey deeply impressed him and contributed to his political views (Communist) and to his generous hospitality. One door at Shakespeare and Company bore the legend “Be not inhospitable to strangers lest they be angels in disguise”(a quotation from WB Yeats).15

After Latin American Studies at Harvard and two years with the Merchant Marine during the Second World War, in 1945 Whitman opened a bookshop at Taunton, Massachusetts. But after failing to raise the money to buy a shop in Boston, he arrived in Paris in 1946 and volunteered at a war orphansshelter. When the camp disbanded, he enrolled to study French Civilization at the Sorbonne.

In the early post-war years, American veterans could claim a generous book allowance by submitting vouchers to the Veterans Association.16 With these, and with vouchers bummed off less literary GIs, he filled his tiny room in the Hotel de Suez, on the boulevard St Michel, with books on literature, philosophy, politics and history.17 His “library” attracted the American “Second World War spillover18” community and became a meeting point for Left-leaning expatriates.

Eventually Whitman decided to open a bookstore, and in 1951, using a small inheritance of $500, he bought the lease on the grocery and filled it with his books. Over the years he bought flats on three floors of the building to expand his premises.

“The Mistral” soon became a venue for the Left Bank literati, with readings and meetings taking place in the back room, often followed by a communal meal cooked by Whitman. Within a few months, the bookshop gave birth to a small literary magazine called Merlin, which published works by Jean Genet, Eugene Ionesco, Jean-Paul Sartre and a then unknown Samuel Beckett.19

A small, withered man with tiny, birdlike eyes, Whitman was as eccentric as his bookshop. He kept his white hair trimmed by singeing the ends with a candle(“faster and cheaper than a barber ... just burn it right away, nothing to it”), and dressed in a range of multicoloured cast-offs from the Salvation Army, wearing them until they became shiny with grime.20 Every Sunday evening he hosted a tea party on the top floor, and in summer he held impromptu dinner parties on the pavement outside the shop.

Whitmans brief marriage to an Englishwoman produced a daughter, Sylvia Beach Whitman, who joined him in the business after leaving university. Together, in 2003, they supported the first “Lost, Beat, New Generations in Parisian Literary Traditions” festival.

Whitmans favourite novel was Dostoyevskys21 The Idiot and he confessed to feeling he was the main character“lost in the labyrinth of existence”. And he slept at the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris, in the good company of other men and women of letters such as Guillaume Apollinaire, Colette, Oscar Wilde and Balzac.22

莎士比亚书店不仅是一间书店;它还是一个图书馆,一家青年旅社,一个文化圣地。正如阿娜伊斯·宁在其20世纪50年代的巴黎日记中所记载的那样:“在塞纳河畔有一家书店……尤特里罗风格的房子,不太稳定的地基,小小的窗户,皱巴巴的百叶窗。店主是乔治·惠特曼,他看起来营养不良,胡子拉碴,站在书堆里活像个圣人;他经营书店,出售并租借图书,虽然他并不着急将图书出手,还留出楼上的小阁楼为身无分文的房客提供落脚之地。在店面最里头,有一间极为拥挤的房间里,仅配有一张书桌和一个小火炉,惠特曼就坐在这儿拆信写信,订购图书,但那些前来寻书的顾客常会进来和他聊会儿天。沿着一段狭窄的环形楼梯向上可以到达惠特曼的卧室,或是他为类似于亨利·米勒等房客准备的合租房间。”

莎士比亚书店最初是由希尔维亚·毕奇这位美国侨民在上世纪初创建起来的,当时也正是巴黎成为了一群旅法外国作家的乌托邦的年代,他们中包括欧内斯特·海明威、埃兹拉·庞德、弗·司各特·菲茨杰拉德等人,被这个城市宽容自由的氛围,便宜的酒店、餐馆和酒吧所吸引,慕名前来。

这家书店成为了英语为母语的作家和知识分子与他们的法国同行的会见交流之地。在詹姆斯·乔伊斯的《尤利西斯》分别被英国和美国出版社贬为淫书而拒绝出版之后,希尔维亚·毕奇于1922年出版了该书,这一举动使得莎士比亚书店闻名于世。然而,在纳粹占领巴黎之后,希尔维亚·毕奇就关闭了书店。

1951年,莎士比亚书店的传统得以延续——乔治·惠特曼盘下了布士锐大街37号一家破产的杂货店。店址在塞纳河左岸,对面就是巴黎圣母院,惠特曼将它改造成一家图书馆和书店的结合体,并取名为“米斯切尔书店”。1964年,希尔维亚·毕奇去世,此后惠特曼为了纪念她就将书店更名为莎士比亚书店。

惠特曼“心灵拾荒者”的美名吸引了新的一批旅法外国作家和文人,其中包括了萨缪尔·贝克特、亨利·米勒、劳伦斯·达雷尔、贝尔托·布莱希特、亚瑟·米勒以及“垮掉的一代”的作家威廉·柏洛兹、劳伦斯·费尔林希提、杰克·凯鲁亚克和艾伦·金斯堡。当威廉·柏洛兹正在创作《裸体午餐》这部小说时,曾向惠特曼询问过关于医学和精神病学方面的书籍。“他对毒品上瘾,”惠特曼回忆道,“而且不太爱说话。”金斯堡则因为曾经将他以每本100美元的价钱卖给惠特曼的带有插画的笔记本悄悄偷回而损坏了他在惠特曼心中的形象。

惠特曼蓬头散发,稍有些怪脾气,却十分慷慨大方。他经营着自己的“小社会主义社区,只是外表看起来像家书店”的地方。在这里,所有现代化的玩意儿都被“大义凛然”地摒弃,比如电话机、监控摄像头,甚至信用卡(当然除了用来顶开大门之外)。店里也没有图书分类:希腊百科全书与战争书籍、现代小说一起随便摆在书架上或堆在地上。

惠特曼对赚钱显得有些漫不经心,不在意得失,常常告诉顾客他们正在阅览的书籍是非卖品,或是在钱箱消失之后——这常常发生——保持冷静。然而,当许多商业化的书店不断被收购或因缺少资金而走投无路时,惠特曼的书店不仅经受住了“垮掉的一代”诗人和嬉皮士这群人的破坏,还平安度过了1968年学生暴动和法国政府名目众多的税务审查。他究竟如何成功做到的还真是个谜。

1913年12月12日,乔治·惠特曼出生于美国马萨诸塞州的塞勒姆县,其父是沃尔特·惠特曼——可不是那位诗人,而是一位四处奔波的物理教授。乔治常常称自己是“沃尔特·惠特曼的私生曾孙子”,但是这——就像他讲述的许多关于自己的故事一样——我们几乎可以完全肯定不是真的。

乔治的童年是在跟随父亲的工作旅行中度过的,先后去过中国、希腊、土耳其和西欧。他在波士顿大学攻读新闻学位,毕业后乔治踏上了漫漫七年的横穿美国、墨西哥和中美洲之旅,期间曾在路边搭过便车、坐过货车车厢,还行过乞,如果能工作就工作。他最初打算是要环游世界,但是他的旅程止步于巴拿马,因为他被困在一片“流沙、泥潭和红树林沼泽的危险地带中”(险些丧命)。

在旅程中他亲身体验了贫穷,被陌生人的仁慈所感动,这些都给他留下了深刻的印象,并促使他形成了自己的政治观点(共产主义)以及他慷慨好客的性格。莎士比亚书店的一扇门上刻着这样的文字:“不要对陌生人不友好,也许他们是伪装的天使”(引自叶芝的诗句)。

惠特曼在哈佛学习拉丁美洲研究,二战时与商船队呆了两年,1945年时在马萨诸塞州陶顿市开了一家书店。但因未能成功筹资在波士顿购买一家新书店,他于1946年来到了巴黎,自愿参加了一个战争孤儿的救助站。当救助站解散后,他就留在索邦大学学习法国文明研究。

战后早期,美国退伍军人可向退伍军人协会提交相关凭证领取一笔丰富的购书津贴。凭着他向其他受教育水平不太高的美国军人索要的凭证和这些购书津贴,惠特曼买了许多文学、哲学、政治和历史方面的书籍,并把他在圣米歇尔林荫大道苏伊士宾馆里的小房间塞得满满的。他的“图书馆”吸引了不少美国“二战流外人士”,成为了他们学习左翼思想的一个聚集地。

惠特曼最终决定要开一家书店,于是1951年,他花了继承的500美元遗产,租下了一家杂货店的店面,摆放上自己的书。经过多年的发展,他买下了这栋建筑的三个楼层,扩充了营业场所的面积。

“米斯切尔书店”很快就成为了左岸文人聚集之地,他们在店面后边的小房间里举行研读会和各种聚会,会后惠特曼还常常亲自下厨为他们提供一顿美餐。短短几个月内,一本小型文学杂志《梅林》在书店中诞生了,刊登了让·热内、欧仁·尤内斯库、让-保罗·萨特以及当时还名不见经传的塞缪尔·贝克特等作家的作品。

惠特曼与他的书店一样,带着一股古怪的气息,他整个人瘦骨如柴,眯着个小鸟儿似的眼睛。他修剪其白头发的办法是:拿起蜡烛将头发梢点燃烧焦(他自称“这比去理发师那儿剪发更快更便宜……而且头发直接烧掉,一点儿都不难”),成天穿着救世军公益组织发放的五颜六色的旧衣服,一直穿到这些衣服都因沾满污垢而闪闪发亮为止。每周日晚上他都在顶楼举办茶话会,而夏季时他还会即兴在书店外面的人行道上举办晚宴。

惠特曼有过一次短暂的婚姻,妻子是英国人,为他生下了一名女儿,希尔维亚·毕奇·惠特曼。希尔维亚大学毕业后就帮着父亲打理书店的生意。2003年,他们俩合作共同举办了主题为“巴黎文学传统中的迷惘的一代、垮掉的一代以及新的一代”的活动。

惠特曼最喜欢的小说是陀思妥耶夫斯基的《白痴》,他承认他觉得自己就像小说中的主人公,“迷失在存在的迷宫里”。乔治·惠特曼长眠于巴黎拉雪兹神父公墓,陪伴他的还有纪尧姆·阿波利奈尔、科莱特、奥斯卡·王尔德、巴尔扎克等伟大文人。

1. Anas Nin: 阿娜伊斯·宁(1903—1977),著名女性日记小说家、西班牙舞蹈家。她被誉为现代西方女性文学的开创者;一生出版了11部日记,主要代表作有《劳伦斯评传》、《玻璃钟下》等。

2. Utrillo: 指的是Maurice Utrillo,莫里斯·尤特里罗(1883—1955),享有“巴黎之子”的美誉,是20世纪法国画坛最杰出的天才画家之一。他画下了大量巴黎街景,用沉郁却亮丽的色彩展现了巴黎风情。

3. Henry Miller: 亨利·米勒,(1891—1980),20世纪美国乃至全世界最重要的作家之一,同时也是极具争议的文学大师和业余画家,被公认为美国文坛“前无古人,后无来者”的一位怪杰。主要代表作有《北回归线》、《南回归线》等。

4. expatriate: 居住在国外的人;Ernest Hemingway: 欧内斯特·海明威(1899—1961),美国记者和作家,被认为是20世纪最著名的小说家之一,是美国“迷惘的一代”(Lost Generation)作家中的代表人物,主要代表作有《老人与海》、《永别了,武器》等;Ezra Pound: 埃兹拉·庞德(1885—1972),是美国著名诗人、文学家,意象主义诗歌的主要代表人物;F. Scott Fitzgerald: 弗·司各特·菲茨杰拉德(1896—1940),美国长篇小说、短篇小说作家,主要代表作有《了不起的盖茨比》、《夜色温柔》等;permissive: 宽容的,自由的。

5. condemn: 谴责,指责;obscene: 淫秽的,猥亵的。

6. Left Bank: (法国巴黎塞纳河的)左岸。巴黎人习惯将塞纳河以北称为右岸,有许多的高级百货商店、精品店及大宾馆;而塞纳河以南称为左岸,有许多学院及文化教育机构,因此在这里以年轻人居多,消费也较便宜。

7. literati: 文人,文学界;Samuel Beckett: 萨缪尔·贝克特(1906—1989),20世纪爱尔兰、法国作家,是荒诞派戏剧的重要代表人物;Lawrence Durrell: 劳伦斯·达雷尔(1912—1990),英国小说家、诗人、剧作家、游记作家;Berthold Brecht:贝尔托·布莱希特(1898—1956),德国戏剧家和诗人,他提出的戏剧理论“陌生化效果”对世界戏剧演出产生了重大的影响;Arthur Miller: 亚瑟·米勒(1915—2005),美国剧作家,他的主要代表作有《推销员之死》等;William Burroughs:威廉·柏洛兹(1914—1997),美国小说家、散文家、社会评论家,身为“垮掉的一代”的主要成员,他是影响流行文化以及文学的前卫作家;Lawrence Ferlinghetti: 劳伦斯·费尔林希提(1919— ),美国诗人、画家、自由主义激进分子,美国著名书店“城市之光”的创始人之一,主要代表作有诗集《心中的科尼岛》等;Jack Kerouac: 杰克·凯鲁亚克(1922—1969),美国小说家、作家、艺术家与诗人;Allen Ginsberg:艾伦·金斯堡(1926—1997),美国诗人,最出名的作品是长诗《嚎叫》。

8. blot your copybook: 做出有损形象的事情,玷污名誉。

9. dishevele d:(头发、衣服或外表)凌乱的,不整洁的;eccentricity:古怪行为,反常;prodigal:浪费的,挥霍的;disdain:鄙弃,鄙视;prise: 〈英〉强行使分开,撬开。

10. encyclopedia: 百科全书;jostle: 挤,堆;stack: 使成叠,使成堆。

11. blithe: 不在意的,漫不经心的;peruse: 细读,研读;occurrence:发生,出现。

12. go to the wall: (因缺少资金)走投无路,失败;weather: 经受住,平安度过(灾难);depredation: 掠夺,破坏;1968 student riots: 指的是1968年春天的法国“五月风暴”学生活动,是始于学生运动、继而演变成整个社会动荡,最后甚至导致了法国政治危机的一场历史事件。

13. itinerant: 四处奔波的,漂泊不定的。

14. odyssey: 艰苦的跋涉,漫长而充满风险的历程;hitchhike: 搭便车;freight car: 货车车厢。

15. legend:〈英〉(标志、硬币等物品上的)刻印文字,铭文;lest:唯恐,以免。

16. veteran: 退伍军人,老兵;voucher: 收据,凭单。

17. bum sth. off sb. : 提出要,乞讨;GI: 美国兵;boulevard: 林荫大道。

18. spillover: 溢出,外流人口。这里指的是在二战期间或由于二战而离开自己祖国的外籍人士。

19. Jean Genet: 让·热内(1910—1986),法国当代著名小说家、剧作家、诗人,主要代表作有《布雷斯特之争》、《小偷日记》等;Eugene Ionesco: 欧仁·尤内斯库(1909—1994),罗马尼亚及法国剧作家,荒诞派戏剧最著名的代表之一,其作品常表现的一个主题是“人生是荒诞不经的”;Jean-Paul Sartre: 让-保罗·萨特(1905—1980),法国思想家、作家,存在主义哲学的大师,其代表作《存在与虚无》是存在主义的经典作品。

20. trim: 修剪;singe: (把表面)轻微烧焦;cast-offs:(自己不穿而赠人的)旧衣服;Salvation Army: 救世军,是一个1865年由维廉和凯瑟琳·卜夫妇在英国伦敦成立的,以基督教作为信仰基本的国际性宗教及慈善公益组织,以街头布道和慈善活动、社会服务著称;grime: 尘垢,污垢。

21. Dostoyevsky: 陀思妥耶夫斯基(1821—1881),俄国作家,其作品影响了许多20世纪的作家,主要代表作有《白痴》、《罪与罚》等。

22. Guillaume Apollinaire: 纪尧姆·阿波利奈尔(1880—1918),法国诗人,被视为20世纪上半期法国最杰出的诗人,主要代表作有《醇酒集》、《图画诗》等;Colette: 科莱特(1873—1954),法国20世纪上半叶的女作家,主要代表作有《吉吉》、《二重唱》等。