Some Reflections on Com piling and Translating The Cassell Dictionary of English Idioms—A Brief Review of Nida’s Guiding Principles of Translation and Leech’s Four Circles of Meaning

Lu Siyuan

(College of Foreign Languages,University of Shanghai for Science and Technology,Shanghai 200093,China)

In the spring of 2002,at the invitation of the Chinese University Press of Hong Kong,the w riter had a joyful occasion to compile and translate the British Cassell Dictionary of English Idioms①The compiler of this dictionary is Rosalind Fergusson,a senior freelance editor and author,whose publications include The Penguin Dictionary of Proverbs(1983),The Ham lyn Dictionary of Quotations(1989) and The Chambers Dictionary of Foreign Words and Phrases(1995)..The dictionary takes a fresh look at some 10 000 English idioms,and most of them are new English phrases and expressions.Before rendering the dictionary into Chinese,the director of the CUPHK asked the w riter to compile 7 500 more English idioms w ith Chinese versions based on the actual situation of China and its culture.To put it more precisely,the dictionary, altogether,contains more than 17 500 English idioms,including adages,proverbs,slangs and racy expressions.As a natural result,it has become a very useful reference tool and guide for the Chinese readers.At the end of 2003,the dictionary came off the press printed by the CUPHK in Hong Kong,and in January of 2006,Beijing University Press bought the copyright from CUPHK and reprinted it in Beijing.

As the painstaking translating and compiling job has been done,the w riter considers it worthwhile to put down some summ ing-up notes as a brief retrospect of that memorable work.

I.How to Translate an English Idiom

To begin w ith,the w riter would like to treat something about the nature of English idioms.As we know,idioms,no matter whether English ones or Chinese ones,are one of the most interesting and difficult parts of vocabulary.English idioms are not only interesting but also colorful and lively[1].However,they are sometimes not so easy to comprehend or to render into appropriate Chinese.That is why an idiom can be defined as a phrase whose meaning cannot be readily understood from its component parts.For instance,the idiom “white hope” is a metaphor,whose practical meaning has nothing to do w ith the word “hope”[2].Actually it refers to a person or a member of a group who is expected to achieve much success or bring glory to his team or people.Why so? It is simply because this idiom originally comes from the sport of boxing,where it refers to a white boxer or fighter who is thought capable of beating a black champion such as Tyson or Hollyfield.Both of them are well-known black boxers in the United States toward the end of the 20th century.So,the Chinese version for “white hope” is not “白色的希望”.The proper version should be “众望所归的人”or “肩负重任的人”.Similarly,the idiom “white lie” does not mean “白色的谎言”,as its real sense is “a pardonable fiction or misstatement”.The proper Chinese version for it should be somewhat like “没有恶意的谎言” or “出于好意而说的谎话”.For instance,there is such an English sentence: “The other day I told Alice a white lie when I said she looked so beautiful.” The Chinese would be “那一天,我对爱丽丝说,你长得真美呀,当时我是说了一句无.伤.大.雅.的.谎.言.”.In the Cassell Dictionary,the lion’s share of the entries belongs to such a type.

In the course of translating and compiling those definitions and examples,the w riter frequently resorted to a number of books or articles on translation theories and techniques for help,particularly whenever or wherever coming across something difficult to render.Among those monographs on the art of translating,he found Eugene A.Nida’s and Geoffrey Leech’s works are most helpful and useful.Of course,Noam Chomsky’s “Surface Structure” and“Deep Structure” also rendered a great help to his translation work[3].

II.Nida’s Guiding Principles of Translating

Before taking some concrete examples from the Cassell Dictionary of English idioms to deal w ith theoretically and rhetorically,the w riter would like to quote some well-known guiding principles of translating from Nida’s works.On page 12 of the book The Theory and Practice of Translation,Eugene A.Nida and his coauthor,Charles R.Taber w rote:

Translating consists in reproducing in the receptor language the closest natural equivalent of the source-language message,first in terms of meaning and secondly in terms of style.Translating must aim primarily at “reproducing the message”…

To do anything else is essentially false to one’s task as a translator.But to reproduce the message one must make a good many grammatical and lexical adjustments…

The translator must strive for equivalence rather than identity.In a sense this is another way of emphasizing the reproduction of the message rather than the conservation of the form of the utterance…[4]

In 1991,Nida w rote another book entitled Language,Culture,and Translating.On page 118,he put forward a new principle,that is “Functional Equivalence” or “Functional Identity”,Nida said,“In general,it is best to speak of ‘functional equivalence’ in terms of a range of adequacy,since no translation is ever completely equivalent[5].So,an ideal definition could be stated as the readers of a translated text should be able to understand and appreciate it in essentially the same manner as the original readers did.”

The above several short passages have made outstanding and profound contributions to the science of translating.Now he’ll demonstrate how he applied Nida’s guiding principles of translating to his own translation works.

In the eighties and nineties of the last century,the editor-in-chief of College English kindly asked the w riter to offer some articles for the magazine.In 1987,the fourth issue of College English published his article “Strive for Equivalence Rather Than Identity”(P55-P59).In that piece of w riting,he dealt w ith Nida’s guiding principles of translating in some detail and then translated the well-known Canadian doctor Norman Bethune’s essay “The True Artist” into Chinese to illustrate his point of view about Nida’s theories of translating.

Now let’s make a comparison between the source language and target language of Dr.Bethune’s “The True Artist”.

The True Artist

Norman Bethune

The true artist lets himself go.He is natural.He“swims easily in the stream of his own temperament.”He listens to himself.He respects himself.

He comes into the light of every-day like a great leviathan of the deep,breaking the smooth surface of accepted things,gay,serious,sportive.His appetite for life is enormous.He enters eagerly into the life of man,all men.He becomes all men in himself.

The function of the artist is to disturb.His duty is to arouse the sleepers,to shake the complacent pillars of the world.He reminds the world of its dark ancestry,shows the world its present,and points the way to its new birth.He is at once the product and preceptor of his time.After his passage we are troubled and made unsure of our too-easily accepted realities.He makes uneasy the static,the set and the still.In a world terrified of change,he preaches revolution—the principle of life.He is an agitator,a disturber of the peace—quick,impatient,positive,restless and disquieting.He is the creative spirit working in the soul of man.

真正的艺术家

诺尔曼·白求恩

真正的艺术家在进行创作时是不受任何约束的。他自由自在,悠然自得地在符合自己个性的川流中畅游。他倾听自己的心声,顺从自己的意愿。

他以深海巨鲸的姿态,出现在我们日常的生活世界,扰乱人们自以为常的平静的生活海洋。他轻松愉快、严肃认真、嬉笑自若。他热爱生活,渴望与各种人物生活在一起,以把他们的特点融为一体。

艺术家的职责就是要在平静的生活海洋里激起波涛,唤醒沉睡的人们,震撼那些自鸣得意的社会栋梁。他提醒世人不要忘记过去暗无天日的岁月,向他们展示当今的世界,并为他们指引新生的道路。他既是时代的产儿,也是时代的先锋。当他们露面之后,人们就惶恐不安,开始对那些本来深信不疑的事物产生了怀疑。他使那些僵死不变,纹丝不动的事物变得动荡不安。在一个惧怕变革的世界里,他公开宣扬,革命乃是生活的源泉。他是一个鼓动家,一个扰乱平静生活的人物——动作敏捷、性格暴躁、办事果断、勤奋不息和令人不安。他是活跃于人类灵魂中富有创造力的精灵。

(卢思源 译)

A fter comparing the original text w ith the translated one,we find there are some striking differences lying between the SL and TL[6].Now let’s deal w ith them one by one.

1.Norman Bethune,in the essay “The True Artist”,employed a great number of rhetorical devices—sim ile,metaphor,metonymy,parallel structure,elegant variation and repetition.The language he used is somewhat like that of free verse.Some words and sentences are ambiguous in sense.They have the ambiguities of the poetic language.That is why we cannot translate the essay in the usual literal way.For instance,the first paragraph should not be turned into:“一个真正的艺术家是到处走动的。他是自然的。他‘在自己气质的小河中遨游’。他倾听自己的声音,他尊敬他自己。”To render those five short sentences into proper Chinese,and reproduce the original image and deep structure meaning,the w riter employed the translation technique of rendering a word conveying abstract notion into a term conveying concrete sense or a general word into a specific one; in the meanwhile,he supplied some words in the sentences by means of amplification.So,his Chinese version for the first paragraph is: 真正的艺术家在进行创作时是不受任何约束的。他自由自在,悠然自得地在符合自己个性的川流中畅游。他倾听自己的心声,顺从自己的意愿。

2.The second point which is worthy of our notice is the choice of words.While rendering something either from English into Chinese or vice versa,we should spare no efforts to find some appropriate and suggestive words to express the delicate shades of meaning of the words in the original[7].Sw ift says well: “Proper words in proper places make the true definition of style”.So,we should be very scrupulous in the choice of words.For instance,in the first paragraph,the w riter turned “He is natural” into “他自由自在”.In the last paragraph,“dark ancestry”became “暗无天日的岁月”,“A fter his passage”became “当他露面之后”.It seems to him such Chinese versions may correspond exactly to those of the original.By means of those effective and clear,intellible expressions,all the profound meaning and artistic qualities of the original are preserved.

3.During the process of translating,we should always keep in mind Nida’s guiding principles of translation—reproducing the closest natural equivalent of source-language message,first in terms of meaning and secondly in terms of style.While reproducing the message,we must make a good many grammatical and lexical adjustments.And finally,the most important point is the translator must strive for equivalence rather than identity.

III.The Significance of Leech’s Four Circles (or Layers) of Meaning

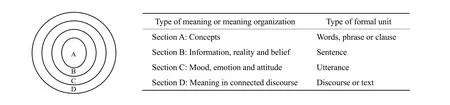

We’ve just introduced American linguist Nida and his views on the guiding principles of translating to you,now we should like to introduce another well-known western school to the readers.The representatives of that school are Geoffrey Leech and Jan Svartvik.In 1974,Leech and Svartvik jointly w rote a book entitled: A Communicative Grammar of English; in that book,on page 12,Part Three,in the section of “To the Teacher”,there is a passage entitled“Grammar in Use”,in which we find 4 circles.These 4 circles represent the 4 different types of meaning and the 4 different ways of organizing meaning.

图1 意义的四个层次Fig.1 Four Circles of Meaning

Now let us explain what these 4 circles mean.

Circle A(or Section A) stands for notional or conceptual meaning.The carrier of concept or notion is a word,a phrase or a clause.In general,the conceptual meaning expresses the referent in a definite and direct way.The conceptual meaning of a word is the definition given in the dictionary.In other words,conceptual meaning is referential,denotative or dictionary meaning.It does not include connotation.For example,the concept of “fireside” is “a place near the fire or hearth”,but its connotative meaning might be “warm th,home,domestic life or retirement”.That is why in rendering an article,it is very important for us to tell denotation from connotation.These two should not be mixed up.

Circle B reprisents logical communication.It is a combination of concepts.The carrier of logical communication is the sentence.As conceptual mean-ings are grouped together and formed into a sentence in a logical way,the association turns up between words; as a result,various associative meanings arise.It should be pointed out here,in Circle B,the meaning of a word w ill undergo “Grow th”,“Expansion”,“Shift” or “Variation”.Therefore,during the translation process,when we come across the sentence here,we should pay great attention to analyze the development and change of the meaning in the second layer.After a while,we’ll cite a concrete example to illustrate this point.

Circle C involves another dimension of communication,that is,the attitude and behavior of the speaker and hearer.At the speaker’s or w riter’s end,the words he speaks or w rites can express attitude or emotions; at the receiving end,the language can control or influence the actions and attitudes of the hearer or the reader.Some students or inexperienced translators are apt to neglect this sort of effective or emotional meaning of the source language; as a result,their renditions are rather dull and not faithful enough to the original.Now we can make a comparison of the follow ing versions and see what affective or emotional meanings are:

Tom lived in the underworld,rubbing shoulders w ith all walks of life that he hated before.

汤姆生活在那个曾经憎恨过的下流社会,与三.教.九.流.的.人.物.来往密切。(cf.各界人士)

No more of your smut excuses! I won’t listen to them.

收起你那些狗.屁.借口吧,我才不听你那.一.套.呢。(cf.肮脏的;那些话)

Circle D deals w ith something about stylistic meaning.It is concerned w ith the follow ing questions: How shall we arrange our thoughts? How shall we bind them together in order to communicate them in the most appropriate or idiomatic way? In short,it concerns how to present your idea in the best way.So,it is a matter of style which a competent translator should not neglect.

Now before we cite a concrete example to illustrate the significance of Leech’s 4 circles or layers of meaning,let’s first go back to Norman Bethune’s essay—“The True Artist”.A moment ago,we dealt w ith the stylistic features and rhetorical devices of that article.We came to know the content and the gist of that piece of w riting.That is,the function and the duty of a true artist is to arouse the sleepers and shake those self-satisfied people,urging them to make revolution; otherw ise our society cannot gain social advancement,the people won’t lead a better life in the future.Only by making continuous revolution,can we gain better days on the morrow.That is the essence and gist of Norman Bethune’s “The True Artist”.Right? If we want to use one single sentence to express the main idea of that essay,most probably that sentence might be somewhat like this:

Our world today is not improved by the com patibles but by the incom patibles.

We know you are able to comprehend or grasp the meaning of this sentence but can you turn it into proper Chinese? I’m afraid not.It’s not easy to render it in a proper way.However,w ith the help of Leech’s 4 circles,most probably you’ll manage to do it.Now let’s see how Leech’s 4 circles work.

As we know,“compatible” and “incompatible”are adjectives.In Circle A,They convey the conceptual meaning: capable(or not capable) of living or perform ing in harmonious combination w ith others.The former is a word conveying good connotation; the latter,conveying bad connotation.When these two words enter Circle B,the formal unit is now a sentence,their grammatical functions have got some changes as two definite articles are put before them; in the meanwhile,“-s” is added to them.So they have become “nouns” now.Their meanings have grown(增生为)into “随和的人” and “不随和的人”.As we mentioned above,in Circle B,a word or the meaning of a word w ill usually undergo “Grow th”(增生),“Expansion”(扩张),“Shift”(转移)or “Variation”(变异).It is worthy of our notice,the development of their meanings has not come to an end yet.As they enter Circle C,the former(compatibles) has degenerated(贬降为) to a word conveying bad sense while the latter has elevated(提升为) to a word conveying good sense —“不随和的人”,that is,from a not self-satisfied person to a reformer or revolutionary(改革派;革命者).It is here,in Circle C,they reflect the affective or emotional meaning,which shows one’s mood,emotion or attitude.As a result,“the compatibles” becomes “随遇而安的人”,“the incompatibles”becomes “不安于随波逐流的人”.When these two words enter Circle D,the layer of stylistic meaning,we present the idea in the best way; that is,the most expressive,elegant,lifelike way.Hence,the complete Chinese version for the above sentence is somewhat like this:

当今世界的进步并不是由那些随遇而安的人而是由那些不安于随波逐流的人促成的。

This sentence is the gist of Norman Bethune’s“The True Artist”.Do you think so? And it has embodied the spirit or requirement of Eugene A.Nida’s guiding principle.And it also reflects Noam Chomsky’s theory about “surface structure” and “deep structure”[8].Also it amply demonstrates the theory and function of Leech’s 4 Circles of Meaning.

To illustrate further the w riter’s point of view about the topic of what we have just dealt w ith,a few more examples are quoted from the Cassell Dictionary of English Idioms.They are as follows:

(1) White hope (Chinese University Press p.616; Beijing University Press p.705)

Do you think Fan Zhiyi is the white hope of our Chinese football team?

How do you translate this sentence into proper Chinese? Now,let us put “white hope” into Leech’s 4 circles.In Circle A,the conceptual meaning is “白色的希望”; when it enters Circle B,it undergoes a“Grow th”,an “Expansion”,a “Shift” or “Variation” in meaning,and it becomes “众望所归的球员” or “肩负重任的人”.Anyhow,he is a footballer who is expected to bring glory or victory to the Chinese football team.And then it enters Circle C,it may become “杰出的球星” “范大将军” or something like that,because in Circle C,we have to supply some sort of emotional or affective meaning; and when it goes through Circle D,we should ponder over its stylistic meaning.Finally,in this way,the Chinese version may be somewhat like this:

你是否认为,范志毅是给我们中国足球队带来胜利之光的大球星呢?

(2) back-seat driver (Chinese University Press p.18; Beijing University Press p.20)

Joe,stop talking.I know what I’m going to do.I don’t need a back-seat driver.

Circle A: a driver sitting at the back seat rather than in the front seat(后座驾驶员)

Circle B: a person in a car who offers unwanted advice to the driver(对司机指手划脚的乘客)

Circle C: a person who offers advice on matters which do not concern him or her(爱管闲事的人)

Circle D: an irresponsible person who offers unasked ,unsound advice(乱提意见不负责任的人)

So,the Chinese version may be somewhat like this:

乔,你别说了,我知道该如何走,用不着你来指手划脚。

By the way,we want to tell you,“back seat” is a dynamic expression.It is very useful.For instance,someone says: “Old Wang,you’d better take a back seat as you’re retired now.” He meant to say: “老王,你现已退休,最好是退居二线(别管那么多了)。”

(3) calf love (Chinese University Press p.64; Beijing University Press p.72)

Bob,you’re under sixteen; she is eighteen.Doesn’t it look like a case of calf love?

Circle A: the love of a calf or puppy(小牛/小狗的爱情)

Circle B: a love felt by a young boy or girl(少年之恋)

Circle C: the love between the boy and the girl is very strong and excited but does not last very long(热烈冲动但不持久的少年之恋)

Circle D: a not reasonable or sensible love between a boy and a girl(少年男女间幼稚可笑的谈情说爱)

Now,after going through the 4 circles,we can turn the above sentence into:

鲍勃,你还不到十六岁,而她是十八岁,这难道不是童年时代幼稚可笑的谈情说爱吗?

One more example here:

Mary wanted to get married at the age of 16,but her parents convinced her that it was only calf love.

玛丽十六岁时就想结婚,但她的父母终于使她明白,这不过是怀春少女一时动情罢了。

(4) to tread on someone’s corns (Chinese Uni-versity Press p.582; Beijing University Press p.666)

I’m afraid I trod on Mary’s corns when I asked her what her husband was doing after he came out of prison.

As we know,“corn” is a painful area of thick hard skin on the finger or foot or near a toe; in Chinese,we call it “鸡眼”.So,in Circle A,the primary or conceptual meaning of this phrase is “踩在某人的鸡眼上”.A fter entering Circle B,it becomes “触犯了某人的痛处”.After going through Circle C and Circle D,it becomes “无意中触犯了某人的忌讳之处”。

According to Noam Chomsky and Geoffrey Leech,“踩在某人的鸡眼上” is only “surface structure meaning” or “conceptual meaning or dictionary meaning”,rather than “deep structure meaning” or “affective meaning plus stylistic meaning”[9].So,we should explore the deep structure meaning under the “corns”.And that is:

我问玛丽她的丈夫在出狱后干些什么事的时候,恐怕是触到了玛丽的痛处。

(5) (even)a worm w ill turn (Chinese University Press p.630; Beijing University Press p.721)

Don’t force him into a corner.Do you know even a worm will turn? Circle A: 不要把它逼到角落里,蠕虫会翻腾。Circle B: 若被逼得太甚,蚯蚓也要翻身抵抗。Circle C: 若被逼之太甚,最听话的人也会起来反抗。

Circle D: 若欺人过甚,最温顺的人也要站起来对抗。

Obviously,after going through the 4 circles,the deep structure meaning of the original sentence is equivalent to: Under extreme provocation even the most humble and subm issive person w ill retaliate.

Therefore,the whole sentence can be translated somewhat like this:

不要把他逼得走投无路,若逼得太甚,最温顺的人也会作困兽斗。

If we make a comparison between the SL and the TL,we’ll find we have produced an ideal Chinese version not only in accordance w ith Leech’s 4 circles (or layers) of meaning,but also w ith Nida’s guiding principles of translating; that is,a rendering of the closest natural equivalent of the source language message,first in terms of meaning and secondly in terms of style.To produce the message,we must make a good many grammatical and lexical adjustments.For instance:

1) the noun “corner” has become a verb “走投无路” by means of “conversion of part of speech”.

2) The imperative sentence has been changed into a subordinate conditional clause by means of grammatical adjustment.

3) “the worm” has become a man(最温顺的人.) and then a beast (困兽.).

4) The verb “w ill turn” has become a noun phrase “困兽之斗”.This is also a grammatical adjustment + lexical adjustment.

IV.Concluding Remarks

Metaphors,such as white hope,white lie,back -seat driver,calf-love,frequently turn up in this Cassell Dictionary.According to Lakoff and Johnson,metaphor is the basic way we human beings live by[10].It is an effective cognitive tool of conceptualization of abstract categories.It can help us dig into the mechanisms of meaning extension of words and improve their competence of using the English language.

Most of the metaphors are hard nuts to crack.It seems to the w riter,the best solution is to resort to Nida’s guiding principles of translating,Leech’s four circles of meaning and Chomsky’s theory of surface structure and deep structure for help.

[1]Newmark P.A Textbook of Translation[M].New York: Prentice-Hall International,1998.

[2]卢思源.新编实用翻译教程[M].南京: 东南大学出版社,2008.

[3]Lu Siyuan.Random remarks on skopostheorie and translation[J].East Journal of Translation,2011,(1): 22-30.

[4]Nida E A,Taber C R.The Theory and Practice of Translation[M].Leidew: E.J.Brill,1982.

[5]Nida E A.Language,Culture,and Translating[M].Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press,2001.

[6]Lu Siyuan.Random remarks on the relation of translatology to grammar,rhetoric,pragmatics and other linguistic sciences[J].Shanghai Journal of Translations for Science and Technology,1990,(3): 1-6.

[7]Munday J.Introducing Translation Studies: Theories and Applications[M].London: Routledge,2001.

[8]卢思源.要动态对等,不要形式对应[J].大学英语,1978,(4): 55-59.

[9]Chomsky N.Syntatic Structures[M].The Hague: Mouton,1957.

[10]Lakoff G,Johnson M.Metaphors We Live by[M].Chicago: The University of Chicago Press,1980.

- 上海理工大学学报(社会科学版)的其它文章

- 论语言学的跨学科研究

- 新世纪我国高校英语专业英语教师专业发展现状研究

- 中国英语专业学习者写作中的词汇使用研究