Expression of HLA-G in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma

Hangzhou, China

Expression of HLA-G in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma

Yan Wang, Zhou Ye, Xue-Qin Meng and Shu-Sen Zheng

Hangzhou, China

BACKGROUND: Human leukocyte antigen G (HLA-G) is a non-classical major histocompatibility complex class I molecule that has multiple immune regulatory functions including the induction of immune tolerance. The detection of HLA-G expression might serve as a clinical marker in the prediction of clinical outcomes for certain types of carcinoma. Currently, we investigated whether or not HLA-G is also expressed in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and whether the expression has clinical value.

METHODS: Serum levels of secreted HLA-G (sHLA-G) were measured by ELISA in 36 patients with HCC, 25 patients with liver cirrhosis (LC) and 25 healthy individuals. The expression of HLA-G in liver tissue was further studied using Western blotting in 36 patients with HCC and 25 with LC. The correlations between HLA-G status and various clinicopathological parameters including survival were analyzed.

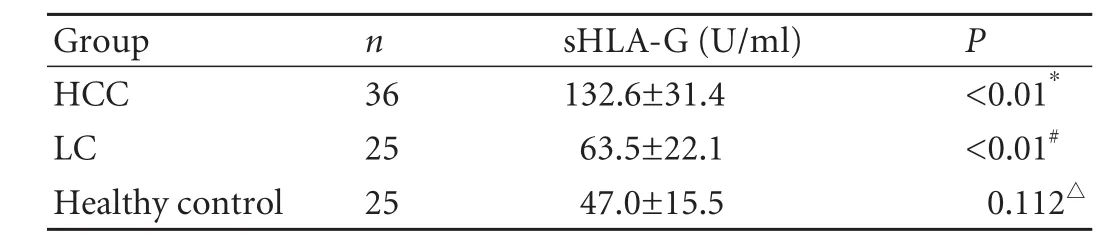

RESULTS: The ELISA assay showed that the serum levels of sHLA-G in the HCC, LC and healthy groups were 132.6± 31.4, 63.5±22.1, and 47.0±15.5 U/ml, respectively. Analysis of variance was used for inter-group comparison and differences were found between the HCC group and the other two groups (bothP<0.01), while no difference was found between the LC group and the healthy group (P=0.112). HLA-G protein expression in liver tissue was found in 66.7% (24/36) of the primary sites of HCC, but not in benign lesions (LC). Further, the HLA-G expression in tumors had no significant correlation with the parameters of age, gender, histological grade and alpha-fetoprotein level. However, patients with HLA-G-positive tumors had a shorter postoperative survival time than those with HLA-G-negative tumors (P=0.014). Also, univariate analysis showed that HLA-G was an independent prognostic factor.

CONCLUSION: Our results indicated that the expression of HLA-G was a characteristic feature of HCC and patients with positive expression of HLA-G in malignant liver tissue had a poor prognosis.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2011; 10: 158-163)

human leukocyte antigen G; hepatocellular carcinoma; prognosis

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the commonly encountered solid tumors worldwide, with at least one million new cases reported each year.[1]It is also the second most common cause of cancer-related death in China and the rest of the world.[2,3]HCC usually presents at a very late stage in its natural history and many patients miss the best opportunity for treatment because of the lack of symptoms in the early stages. Although researchers all over the world have spent decades studying HCC, there is still no reliable clinical marker for its diagnosis and prediction of the clinical outcome.

Human leukocyte antigen G (HLA-G) is a nonclassical major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class Ib antigen. Although the organization of the HLA-G gene is similar to MHC class Ia genes, it has a unique promoter region and uses posttranscriptional splicing of HLA-G mRNA to generate both membrane-bound and soluble isoforms (HLA-G1 to G4, and HLA-G5 to G7, respectively). In non-pathological situations, expression of HLA-G is restricted to the fetal-maternal interface of the extravillous cytotrophoblasts, placental chorionic endothelium, thymic epithelial cells, and erythropoietic lineage cells from the bone marrow,[4]as well as other immune-privileged tissues such as the cornea,[5]nail matrix,[6]and autologous tissues such as the pancreas.[7]

However, HLA-G antigens have been unexpectedly found in various types of human malignancies including renal cell carcinoma,[8]carcinomas of the lung,[9]breast,[10]and ovary,[11]endometrial adenocarcinoma,[12]gastrointestinal cancer,[13]and colorectal cancer[14]as well as hematolymphoid malignancies such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma.[15]Furthermore, secreted HLA-G (sHLA-G) has also been detected in some of these tumor types.[16]These studies have provided considerablein vivoevidence demonstrating HLA-G expression in human tumor tissues and support the view that HLA-G may participate in tumor development by suppressing immune regulation within the tumor microenvironment.[17]

Remarkably, the detection of HLA-G was reported to be correlated with certain clinicopathological parameters in gastric carcinoma,[18]lymphoma,[19,20]ovarian[21]and endometrial carcinoma.[12]These data indicate that HLA-G might serve as a clinical marker in the prediction of clinical outcomes of these diseases. In the current study, we determined whether HLA-G was detectable in HCC, and then whether the detection of HLA-G proteins in HCC could be used as a reliable prognostic marker.

Methods

Specimens and patient data

A total of 36 patients (30 males and 6 females) with HCC were diagnosed and surgically treated between 2004 and 2006 at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (Hangzhou, China). Their mean age at the time of diagnosis was 49 years (range 30-67 years). The clinicopathological findings were determined according to the classification of malignant tumors as identified by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and International Union Against Cancer (UICC) Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) staging system. Of the 36 patients, 12 (33.3%) were classified in stage I/II and 66.7% (24/36) in stage III/IV. In terms of histological grade, the number of well differentiated, moderately differentiated, and poorly differentiated cases were 5 (13.9%), 23 (63.9%) and 8 (22.2%), respectively. The percentage of cases in which preoperative alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) serum levels exceeded 400 ng/L was 52.8% (19/36). Tumor samples were collected after surgical resection. All histologic samples were obtained from the primary lesions in the liver. No specimens from metastatic disease sites were included. All tissue specimens were subjected to microscopic confirmation of pathologic features before their inclusion in the study. Blood samples were obtained preoperatively.

In addition, 25 patients with liver cirrhosis (LC) (age range 35-71 years) and 25 healthy people (age range 23-70 years) were recruited as controls. Liver cirrhosis tissue was obtained by biopsy.

ELISA assay for soluble HLA-G

The levels of β2-microglobulin-associated sHLA-G molecules (shed HLA-G1 and G5 isoforms) in serum samples from 36 patients with HCC, 25 patients with LC and 25 healthy people were measured using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (sHLA-G ELISA, Cat. No. RD194070100) according to the manufacturer's instructions (BioVendor Laboratory Medicine, Inc. and EXBIO, Czechoslovakia). The sensitivity of the assay in detecting sHLA-G was 1 U/ml.

Western blotting analysis

The same amount (20 µg) of total protein from each hepatocellular carcinoma was heated for 3 minutes at 95 ℃ before loading and separated on 12% Tris-glycine-SDS polyacrylamide gels (Novex, USA) and electroblotted to Millipore Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The filters were blocked with 5% non-fat dried milk in TBST for 2 hours at room temperature and incubated with HLA-G (MEM-G1) (Abcom, USA) diluted at 1∶200 overnight at 4 ℃. After washing with TBST, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidaseconjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibody (Amersham, USA) for 1 hour at room temperature. After additional washes in TBST, signals were detected using Enhanced Chemiluminescence Plus reagent (Amersham, USA).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed statistically using SPSS 13.0 (IL, USA). Analysis of variance of the medians was used to assess the difference in sHLA-G levels in malignant versus benign and healthy samples. Studies of the association between HLA-G expression in tumor lesions and clinicopathologic parameters and the overall survival rate were undertaken using the Chi-square test. The tumor recurrence and overall survival were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and the differences were compared with the log-rank test. Cox's proportional hazard model with the forward maximum likelihood estimation was used in multivariable analysis.Pvalues less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Serum levels of sHLA-G in healthy individuals

To set up reference values for sHLA-G levels, healthy males (n=15) and females (n=10) were studied. The sHLA-G level in blood samples from these controls was 47.0±15.5 U/ml (Table 1). In the cohort of 25 untreated patients with LC and 36 with HCC, the meanpreoperative serum levels of sHLA-G were higher than in controls (132.6±31.4 and 63.5±22.1 U/ml). First, Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA was used to compare median values among the three groups, then the Mann-WhitneyUtest (Moses) was used for inter-group comparisons. Differences were found between the HCC and LC groups (P<0.01), as well as between the HCC and control groups (P<0.01), but there was no difference between the LC and control groups (P=0.112).

Table 1. sHLA-G serum levels in healthy controls and patients with HCC and LC (mean±SD)

Fig. 1. HLA-G protein in HCC and LC lesions by Western blotting. HLA-G expression was detected in 24 of 36 patients with HCC (+), while no HLA-G expression was detected in LC patients (-).

HLA-G protein expression in HCC and LC lesions

Western blotting analysis was performed to determine HLA-G protein expression in a series of HCC and LC lesions. A 39-kDa band corresponding to the HLA-G protein was confirmed in 24 HCC lesions but not in the LC lesions, suggesting that HLA-G expression frequently occurs in HCC (Fig. 1).

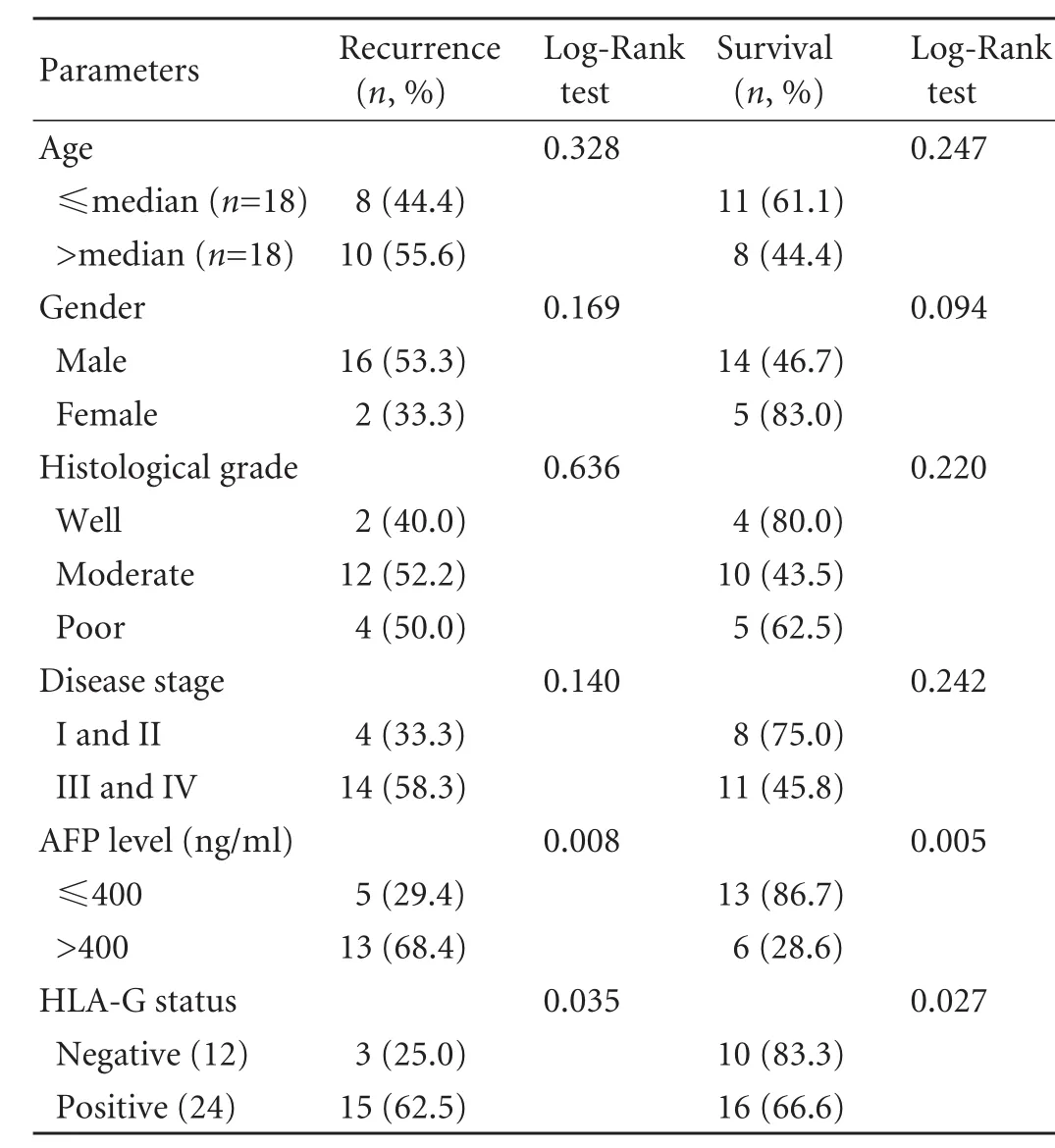

Correlation with clinicopathological parameters

To assess the role of HLA-G expression in HCC, we calculated the correlations between HLA-G expression and the clinicopathological parameters age, gender, histological grade, stage of disease and preoperative AFP level (Table 2). However, no significant correlation was found between HLA-G expression and these parameters.

Correlation with patient survival

Within the 48-month post-assay follow-up period, 17 cancer-related deaths occurred. Of the 12 patients who were HLA-G-negative, 2 died, while among the 24 HLA-G-positive patients, 15 died (Fig. 2). In the entirecohort, the overall survival rate for patients with HLAG-negative tumors was significantly higher than in those with HLA-G-positive tumors (Table 3).

Table 2. Relationship between clinicopathological parameters and HLA-G status in the 36 patients with HCC

Table 3. Effect of HLA-G status on outcome for the entire cohort with available follow-up data

Fig. 2. Correlation with survival of HLA-G positive and HLA-G negative patients.

To further compare with other clinicopathological parameters, the effects of age, gender, histological grade, stage of disease, preoperative AFP level and HLA-G status on patient survival were also analyzed by the log-rank test. The results revealed that age, gender,histological grade and disease stage were not significant variables for predicting tumor recurrence and survival, while preoperative AFP level and HLA-G expression were significantly related to prognosis (Table 4).

Cox's proportional hazard regression model was used to assess the possible prognostic impact of HLA-G expression on HCC. The univariate analysis of these variables revealed that preoperative AFP level and HLA-G expression correlated with a poor prognosis, and were statistically significant (Table 5). These analyses suggest that HLA-G expression in tumor cells is an independent prognostic factor for HCC patients.

Table 4. Kaplan-Meier estimates of recurrence and survival rate dependent on clinicopathological parameters with HCC after follow-up of 48 months

Discussion

There is strong circumstantial evidence that tumor progression can be actively controlled by the host immune system. In recent years, it has been demonstrated that HLA-G plays an important role in mediating immune tolerance by suppressing alloreactive CD4+T-cell proliferation[22,23]and inhibiting NK-cell-mediated and T-cell-mediated cytolysis.[24,25]HLA-G was also found to induce the development of tolerogenic dendritic cells that promote the differentiation of both anergic and regulatory (suppressor) CD4+and CD8+T cells.[26]Soluble HLA-G induces apoptosis in CD8+T and NK cells by binding to CD8, and via a Fas/FasL-dependent mechanism in a model of PHA-stimulated lymphocytes.[27]Thus, expression of HLA-G could afford a potent mechanism of immunologic tolerance by tumor cells.

There has been increased interest in studying HLA-G expression in neoplastic diseases based on the attractive hypothesis that cancer cells likely use HLA-G expression to escape host immunosurveillance. In addition to its potential use as a marker in distinguishing intermediate trophoblastic tumors and tumor-like lesions, HLA-G might also be useful in predicting the clinical outcome in some cancer patients. Although many studies on HLA-G expression in various types of tumor have been reported, studies on HCC have been few.[25]

Here we showed the existence of sHLA-G in a study of sera from 36 HCC patients and 25 LC patients; we also tested serum samples from 25 healthy individuals as a control group. The concentration of soluble HLA-G was similar in the control and LC groups, while it was significantly elevated in the HCC group. The differences between the HCC and control groups, and between the HCC and LC groups were both statistically significant. It is supposed that sHLA-G is more frequently present in malignant lesions than in benign lesions and healthy controls. These results are similar to those in patients with breast and ovarian cancer, where sHLA-G levels are increased compared to healthy controls.[16]Inaddition, Singer et al[28]found that sHLA-G levels are also significantly higher in malignant ascites than in benign controls.

Table 5. Univariate Cox-regression analysis of variables related to HCC recurrence and survival

As sHLA-G can inhibit the functions of T and NK cells, high concentrations should, systemically or at the tumor site, reduce the immune surveillance and thus favour the progression of cancer. Although several protein markers have been studied including AFP, carcinoembryonic antigen, CA19-9 and CA15-3,[29]none of them are specific enough for cancer diagnosis because these markers are also expressed in a variety of normal tissues, benign tumors, and non-neoplastic diseases. It has been hypothesized that we may improve the early diagnosis rate of tumors by detecting sHLA-G in combination with other conventional tumor markers such as AFP levels. AFP is still one of the most important indictors in the diagnosis of HCC. The AFP level may increase in patients with acute hepatitis, chronic active hepatitis or LC. But in our study, HLA-G protein was not detected in LC lesions. Thus it is possible to reduce the false positive rate of AFP testing clinically, which may be conducive to early diagnosis of HCC, through simultaneously detecting the levels of AFP and other tumor markers. This may provide a novel molecular approach to supplement cytological examination in diagnosing tumors. In order to achieve clinical application, we need to further improve the sensitivity of sHLA-G ELISA and verify the accuracy of this method by testing a larger number of samples.

In the current study, HLA-G protein was expressed in the majority of HCC specimens (24/36). Although the literature about HLA-G expression in tumors is conflicting,[30]our data provided definite evidence of HLA-G expression in HCC. In addition, LC tissue lacked any positive expression of HLA-G protein. This is consistent with other reported data[16,25,31]and strongly supports the notion that HLA-G expression is a highly specific marker for malignant transformation.[12,14,24]Clinicopathologic elements were analyzed by the Chisquare test but HLA-G expression showed no association with the clinicopathologic parameters such as age, gender, histological grade, disease stage and preoperative AFP level. These results differ from the reported data on colorectal cancer[14]and gastric carcinoma.[18]Moreover, we found that patients with HLA-G-positive tumors had shorter survival rates than patients with HLA-G-negative tumors and univariate analyses also suggested that HLA-G status, like preoperative AFP level, was a strong predictor of the final clinical outcome. It is hypothesized that both HLA-G positivity and high AFP levels in tumor patients predict a poor prognosis after surgery. However, Ibrahim et al[32]reported that HLA-G expression in melanomas does not correlate with survival. The difference may be explained by the fact that the experiments were performed on different malignant lesions. Hence, to fully substantiate the concept, further investigations are needed.

Considering the immunomodulatory functions of HLA-G, the aberrant expression of HLA-G antigens by malignant cells is suggested to be one of the strategies used by tumor cells to escape immune surveillance. This might grant them survival advantages over HLAG-negative tumors, and ultimately lead to unfavorable clinical outcomes.[16]Besides the altered genomic controls, the upregulation of HLA-G expression has been proposed to be affected by tumor environmental factors such as stress, hypoxia, cytokines and agents used in chemotherapy. Davidson et al[21]revealed that HLA-G could be a new prognostic marker in ovarian cancer and it may be a marker of tumor cell susceptibility to chemotherapeutic agents. Therefore, the detection of HLA-G expression might be beneficial in planning adjuvant therapy for some malignancies, especially when an immunotherapy has already been planned. This discovery suggests that HLA-G status could be a valuable marker for monitoring chemotherapy as well. In addition, HLA-G might be a potential target for an antibody-based therapy in patients with gastric carcinoma.

In conclusion, HLA-G is expressed in the majority of HCC. HLA-G expression, as measured by ELISA in sera and Western blotting in the primary malignant lesions, has a strong and independent prognostic value, indicating that patients with positive HLA-G expression in malignant liver tissue have a poor prognosis, and that detection of HLA-G expression is a useful prognostic marker.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the Major Program of the Science and Technology Bureau of Zhejiang Province (2008F70056).

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the hospital.

Contributors: WY proposed the study. YZ and MXQ wrote the first draft. YZ analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. ZSS is the guarantor.

Competing interest: No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Lau WY. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J R Coll Surg Edinb 2002;47:389-399.

2 Yang L, Parkin DM, Ferlay J, Li L, Chen Y. Estimates of cancer incidence in China for 2000 and projections for 2005. CancerEpidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14:243-250.

3 Parkin DM, Bray FI, Devesa SS. Cancer burden in the year 2000. The global picture. Eur J Cancer 2001;37:S4-66.

4 Carosella ED, Moreau P, Le Maoult J, Le Discorde M, Dausset J, Rouas-Freiss N. HLA-G molecules: from maternal-fetal tolerance to tissue acceptance. Adv Immunol 2003;81:199-252.

5 Le Discorde M, Moreau P, Sabatier P, Legeais JM, Carosella ED. Expression of HLA-G in human cornea, an immuneprivileged tissue. Hum Immunol 2003;64:1039-1044.

6 Ito T, Ito N, Saathoff M, Stampachiacchiere B, Bettermann A, Bulfone-Paus S, et al. Immunology of the human nail apparatus: the nail matrix is a site of relative immune privilege. J Invest Dermatol 2005;125:1139-1148.

7 Cirulli V, Zalatan J, McMaster M, Prinsen R, Salomon DR, Ricordi C, et al. The class I HLA repertoire of pancreatic islets comprises the nonclassical class Ib antigen HLA-G. Diabetes 2006;55:1214-1222.

8 Bukur J, Rebmann V, Grosse-Wilde H, Luboldt H, Ruebben H, Drexler I, et al. Functional role of human leukocyte antigen-G up-regulation in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 2003;63: 4107-4111.

9 Urosevic M, Kurrer MO, Kamarashev J, Mueller B, Weder W, Burg G, et al. Human leukocyte antigen G up-regulation in lung cancer associates with high-grade histology, human leukocyte antigen class I loss and interleukin-10 production. Am J Pathol 2001;159:817-824.

10 Lefebvre S, Antoine M, Uzan S, McMaster M, Dausset J, Carosella ED, et al. Specific activation of the non-classical class I histocompatibility HLA-G antigen and expression of the ILT2 inhibitory receptor in human breast cancer. J Pathol 2002;196:266-274.

11 Davidson B, Risberg B, Berner A, Bedrossian CW, Reich R. The biological differences between ovarian serous carcinoma and diffuse peritoneal malignant mesothelioma. Semin Diagn Pathol 2006;23:35-43.

12 Barrier BF, Kendall BS, Sharpe-Timms KL, Kost ER. Characterization of human leukocyte antigen-G (HLA-G) expression in endometrial adenocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:25-30.

13 Hansel DE, Rahman A, Wilentz RE, Shih IeM, McMaster MT, Yeo CJ, et al. HLA-G upregulation in pre-malignant and malignant lesions of the gastrointestinal tract. Int J Gastrointest Cancer 2005;35:15-23.

14 Ye SR, Yang H, Li K, Dong DD, Lin XM, Yie SM. Human leukocyte antigen G expression: as a significant prognostic indicator for patients with colorectal cancer. Mod Pathol 2007; 20:375-383.

15 Urosevic M, Willers J, Mueller B, Kempf W, Burg G, Dummer R. HLA-G protein up-regulation in primary cutaneous lymphomas is associated with interleukin-10 expression in large cell T-cell lymphomas and indolent B-cell lymphomas. Blood 2002;99:609-617.

16 Rebmann V, Regel J, Stolke D, Grosse-Wilde H. Secretion of sHLA-G molecules in malignancies. Semin Cancer Biol 2003; 13:371-377.

17 Rouas-Freiss N, Moreau P, Ferrone S, Carosella ED. HLA-G proteins in cancer: do they provide tumor cells with an escape mechanism Cancer Res 2005;65:10139-10144.

18 Yie SM, Yang H, Ye SR, Li K, Dong DD, Lin XM. Expression of human leukocyte antigen G (HLA-G) correlates with poor prognosis in gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:2721-2729.

19 Sebti Y, Le Friec G, Pangault C, Gros F, Drénou B, Guilloux V, et al. Soluble HLA-G molecules are increased in lymphoproliferative disorders. Hum Immunol 2003;64:1093-1101.

20 Nückel H, Rebmann V, Dürig J, Dührsen U, Grosse-Wilde H. HLA-G expression is associated with an unfavorable outcome and immunodeficiency in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2005;105:1694-1698.

21 Davidson B, Elstrand MB, McMaster MT, Berner A, Kurman RJ, Risberg B, et al. HLA-G expression in effusions is a possible marker of tumor susceptibility to chemotherapy in ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2005;96:42-47.

22 Bainbridge DR, Ellis SA, Sargent IL. HLA-G suppresses proliferation of CD4(+) T-lymphocytes. J Reprod Immunol 2000;48:17-26.

23 Lila N, Rouas-Freiss N, Dausset J, Carpentier A, Carosella ED. Soluble HLA-G protein secreted by allo-specific CD4+ T cells suppresses the allo-proliferative response: a CD4+ T cell regulatory mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001;98: 12150-12155.

24 Wiendl H, Mitsdoerffer M, Hofmeister V, Wischhusen J, Bornemann A, Meyermann R, et al. A functional role of HLA-G expression in human gliomas: an alternative strategy of immune escape. J Immunol 2002;168:4772-4780.

25 Lin A, Chen HX, Zhu CC, Zhang X, Xu HH, Zhang JG, et al. Aberrant human leucocyte antigen-G expression and its clinical relevance in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cell Mol Med 2010;14:2162-2171.

26 Ristich V, Liang S, Zhang W, Wu J, Horuzsko A. Tolerization of dendritic cells by HLA-G. Eur J Immunol 2005;35:1133-1142.

27 Contini P, Ghio M, Poggi A, Filaci G, Indiveri F, Ferrone S, et al. Soluble HLA-A,-B,-C and -G molecules induce apoptosis in T and NK CD8+ cells and inhibit cytotoxic T cell activity through CD8 ligation. Eur J Immunol 2003;33:125-134.

28 Singer G, Rebmann V, Chen YC, Liu HT, Ali SZ, Reinsberg J, et al. HLA-G is a potential tumor marker in malignant ascites. Clin Cancer Res 2003;9:4460-4464.

29 Sari R, Yildirim B, Sevinc A, Bahceci F, Hilmioglu F. The importance of serum and ascites fluid alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, CA 19-9, and CA 15-3 levels in differential diagnosis of ascites etiology. Hepatogastroenterology 2001;48:1616-1621.

30 Seliger B, Abken H, Ferrone S. HLA-G and MIC expression in tumors and their role in anti-tumor immunity. Trends Immunol 2003;24:82-87.

31 Cai MY, Xu YF, Qiu SJ, Ju MJ, Gao Q, Li YW, et al. Human leukocyte antigen-G protein expression is an unfavorable prognostic predictor of hepatocellular carcinoma following curative resection. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:4686-4693.

32 Ibrahim EC, Aractingi S, Allory Y, Borrini F, Dupuy A, Duvillard P, et al. Analysis of HLA antigen expression in benign and malignant melanocytic lesions reveals that upregulation of HLA-G expression correlates with malignant transformation, high inflammatory infiltration and HLA-A1 genotype. Int J Cancer 2004;108:243-250.

Received April 10, 2010

Accepted after revision November 15, 2010

Author Affiliations: Division of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery; Key Laboratory of Combined Multi-organ Transplantation, Ministry of Public Health; and Key Laboratory of Organ Transplantation Zhejiang Province, First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310003, China (Wang Y, Ye Z, Meng XQ and Zheng SS)

Shu-Sen Zheng, MD, PhD, FACS, Key Laboratory of Combined Multi-organ Transplantation, Ministry of Public Health, First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou 310003, China (Tel: 86-571-87236570; Fax: 86-571-87236884; Email: shusenzheng@zju.edu.cn)

© 2011, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2011年2期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2011年2期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Cholangiocarcinoma accompanied by desmoid-type fibromatosis

- Outcomes of loco-regional therapy for down-staging of hepatocellular carcinoma prior to liver transplantation

- Usefulness of an algorithm for endoscopic retrieval of proximally migrated 5Fr and 7Fr pancreatic stents

- Kupffer cells contribute to concanavalin A-induced hepatic injury through a Th1 but not Th17 type response-dependent pathway in mice

- Is the pancreas affected in patients with septic shock?

-- a prospective study - GPC3 fused to an alpha epitope of HBsAg acts as an immune target against hepatocellular carcinoma associated with hepatitis B virus